Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the effect of case-finding for depression on frequency of depression diagnoses, prescriptions for antidepressant medications, prevalence of depression, and health care utilization during 2 years of follow-up in elderly primary care patients.

DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial.

SETTING

Thirteen primary care medical clinics at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, an HMO in Oakland, Calif, were randomly assigned to intervention conditions (7 clinics) or control conditions (6 clinics).

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 2,346 patients aged 65 years or older who were attending appointments at these clinics and completed the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). GDS scores of 6 or more were considered suggestive of depression.

INTERVENTIONS

Primary care physicians in the intervention clinics were notified of their patients' GDS scores. We suggested that participants with severe depressive symptoms (GDS score ≥ 11) be referred to the Psychiatry Department and participants with mild to moderate depressive symptoms (GDS score of 6 –10) be evaluated and treated by the primary care physician. Intervention group participants with GDS scores suggestive of depression were also offered a series of organized educational group sessions on coping with depression led by a psychiatric nurse. Primary care physicians in the control clinics were not notified of their patients' GDS scores or advised of the availability of the patient education program (usual care). Participants were followed for 2 years.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Physician diagnosis of depression, prescriptions for antidepressant medications, prevalence of depression as measured by the GDS at 2-year follow-up, and health care utilization were determined. A total of 331 participants (14%) had GDS scores suggestive of depression (GDS ≥ 6) at baseline, including 162 in the intervention group and 169 in the control group. During the 2-year follow-up period, 56 (35%) of the intervention participants and 58 (34%) of the control participants received a physician diagnosis of depression (odds ratio [OR], 1.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6 to 1.6; P = .96). Prescriptions for antidepressants were received by 59 (36%) of the intervention participants and 72 (43%) of the control participants (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.2; P = .3). Two-year follow-up GDS scores were available for 206 participants (69% of survivors): at that time, 41 (42%) of the 97 intervention participants and 54 (50%) of the 109 control participants had GDS scores suggestive of depression (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4 to 1.3; P = .3). Comparing participants in the intervention and control groups, there were no significant differences in mean GDS change scores (−2.4 ± SD 3.7 vs −2.1 SD ± 3.6; P = .5) at the 2-year follow-up, nor were there significant differences in mean number of clinic visits (1.8 ± SD 3.1 vs 1.6 ± SD 2.8; P = .5) or mean number of hospitalizations (1.1 ± SD 1.6 vs 1.0 ± SD 1.4; P =.8) during the 2-year period. In participants with initial GDS scores >11, there was a mean change in GDS score of −5.6 ± SD 3.9 for intervention participants (n =13) and −3.4 ± SD 4.5 for control participants (n = 21). Adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics between groups did not affect results.

CONCLUSIONS

We were unable to demonstrate any benefit from case-finding for depression during 2 years of follow-up in elderly primary care patients. Studies are needed to determine whether case-finding combined with more intensive patient education and follow-up will improve outcomes of primary care patients with depression.

Keywords: depression, primary health care, randomized controlled trials, elderly

Depression is a common, serious, and treatable disease that causes substantial morbidity in primary care patients.1,2 Particularly in the elderly, depression leads to greater medical illness, disability, functional decline, and mortality.3–6 Depression meets most criteria for case-finding. It is a common disease with significant morbidity, the cost and risk of case-finding are low, and effective therapy is available. But whether early detection and treatment improves the outcomes of depressed patients is unclear.7–12 Neither the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force nor the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination has found sufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of case-finding questionnaires for depression in primary care patients.13,14

To determine the effect of case-finding for depression, using a previously validated questionnaire, on frequency of depression diagnoses, prescriptions for antidepressant medications, prevalence of depression, and health care utilization in elderly primary care patients, we randomly assigned 13 primary care clinics at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Oakland, Calif, to intervention or control conditions. Intervention clinic physicians were notified of their patients' scores on a case-finding instrument for depression; control clinic physicians were not notified of their patients' scores. Participants were followed for 2 years.

METHODS

Subjects

The study was conducted in 13 primary care clinics at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, an HMO in Oakland, Calif. These clinics have more than 80,000 visits annually from patients aged 65 years or older (approximately 320 visits per day). Each clinic is served by 6 to 8 primary care physicians (approximately 90% general internists and 10% family physicians). We used simple (computer-generated) randomization to assign each of the 13 primary care clinics to the intervention (7 clinics) or control conditions (6 clinics). Between June 1994 and October 1995, a research assistant rotated through these clinics in the assigned random order. A total of 2,896 consecutive patients aged 65 years or older who were attending appointments in these clinics on the days the research assistant was present were eligible to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

To identify patients with depression, a research assistant administered the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) to all eligible patients. This case-finding instrument is a validated and reliable, self-report, symptom checklist designed to detect the presence of current depression in the elderly.15 Using a cutpoint of 6 or more, the GDS has a sensitivity of 88% to 92% and specificity of 62% to 81%, as compared with a structured clinical interview for depression.16,17 We defined depression as a GDS score of 6 or more, with a score of 6 to 10 indicating mild to moderate depressive symptoms, and a score of 11 or more indicating severe depressive symptoms.18 The GDS took approximately 4 minutes to complete and score.

Characteristics of Participants

We identified the age, gender, ethnicity, and marital status of all participants from the Kaiser Permanente administrative database. Self-reported education, income, employment, smoking, and perceived health status (excellent/good vs fair/poor/very poor) were determined from a follow-up telephone interview. To detect the presence of current problem drinking, subjects were asked the 4 CAGE questions for alcoholism,19 modified to detect problem drinking in the past year. We used a score of 2 or greater on the CAGE questionnaire to identify patients with problem drinking.20

We obtained the number of clinic visits and hospitalizations during the 12 months prior to the intervention from the Kaiser Permanente administrative database. We identified antidepressant use during the 12 months prior to the intervention using the computerized Kaiser Permanente Pharmacy Information Management System. Medical comorbidity was determined by assigning scores from the Charlson comorbidity index21 to diagnoses listed on computerized outpatient physician diagnosis forms during the 2-year follow-up period.

To determine the validity of assessing medical comorbidity by assigning scores from the Charlson comorbidity index to diagnoses listed on the physician diagnosis forms, we reviewed medical records from a random selection of 24 participants, assigned scores adapted from the Charlson comorbidity index to the diagnoses listed in these medical records, then calculated the correlation between these scores and those obtained from the diagnosis forms. Scores based on the medical record review strongly correlated with scores based on the physician diagnosis forms (r = .75).

Intervention

We provided a 1-hour educational session for all physicians in both intervention and control clinics to improve their management skills of depression, specifically in the areas of diagnosis and drug therapy. Approximately 60% of physicians attended these sessions, which included instruction in assessment of depression, differential diagnosis, suicidal risk assessment and management of depression, treatment options, duration of treatment, and evaluation of dementia versus pseudo-dementia.

Primary care physicians in the intervention clinics were notified of each participant's GDS score on the day of the participant's visit to the medical clinic (physicians were notified before the participant's appointment 74% of the time and after the participant's appointment 26% of the time) and given an instruction sheet indicating the ranges of scores associated with depression. It was suggested that physicians refer participants with severe depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 11) to the Psychiatry Department, and evaluate and treat participants with mild to moderate depressive symptoms (GDS scores of 6–10) themselves.

In addition, intervention clinic participants with depression were offered a series of organized educational group sessions on coping with depression. Family members were invited to attend the group sessions. This series, which consisted of 6 weekly educational sessions followed by 1 booster session 4 to 6 months later, was developed by a psychiatrist and led by a psychiatric nurse. Topics included the nature of depression, its clinical course, physical and emotional manifestations, relation to other medical conditions, treatment alternatives, medications and their side effects, coping mechanisms, and preventive strategies. Sessions were conducted at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center Psychiatry Clinic.

Primary care physicians in the control clinics were not notified of their patients' GDS scores or advised of the availability of the patient education program (usual care); the GDS scores of subjects who had appointments in the control clinics were not calculated until the time of the follow-up interview.

Outcome Variables

We obtained data regarding physician diagnosis of depression, prescriptions for antidepressants, and health care utilization during the 2-year follow-up period for all participants. Physician diagnosis of depression was determined by blinded review of all outpatient physician diagnosis forms, coded according to the International Classifications of Diseases, Ninth Revision,22 during the 24 months following randomization. To identify diagnoses of depression not recorded on the diagnosis forms, we also asked participants at the follow-up telephone interview whether they had been diagnosed with depression.

Prescriptions for antidepressant medications were determined by blinded review of the Kaiser Permanente computerized Pharmacy Information Management System. Over 90% of patients followed at Kaiser Permanente medical center fill their prescriptions at Kaiser Permanente pharmacies, and thus this database gives an accurate assessment of antidepressant medication use. We also asked participants at the follow-up telephone interview whether they had obtained antidepressant medication outside the Kaiser Permanente pharmacy.

We determined health care utilization (number of clinic visits and hospitalizations during the 24 months following the intervention) using blinded review of the Kaiser Permanente administrative database. Self-reported number of health care visits and hospitalizations at facilities other than Kaiser Permanente was assessed at the follow-up telephone interview.

We defined depression as a score of 6 or more on the GDS at 2-year follow-up. We administered the GDS to all subjects by telephone between May and November 1997, approximately 2 years (mean 26 ± SD 4 months) following randomization. The follow-up telephone interviews were administered by trained research assistants who were blinded to group assignment. Telephone interviews have good validity and reliability compared with face-to-face diagnostic interviews for depression.23,24

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that this study would require 200 participants (100 per group) with depression at baseline to detect a 20% (40% vs 60%) or greater difference in the proportion of participants with depression at 2-year follow-up (80% power; 2-tailed α = .05), or a 1.4-point difference in mean GDS change scores at 2-year follow-up. Assuming a 10% prevalence of depression at baseline and 15% loss to follow-up, we calculated that we would need to recruit 2,350 participants. Of these, we estimated that 235 participants would have depression at baseline, and that 200 (100 intervention and 100 control) of the 235 would complete the 2-year follow-up interview.

Baseline characteristics of intervention and control clinic participants were compared using χ2tests for dichotomous and categorical variables, and t tests for continuous variables. We used paired t tests to examine within-group differences in GDS scores between baseline and follow-up and standard t tests to compare GDS change scores between the intervention and control groups. We used generalized linear models to compare follow-up adjusted mean GDS change scores and health care utilization in the intervention and control groups, adding any variables from Table 1 that were associated (at P < .05) with these outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 331 Participants*

| Variable | Intervention (n = 162), % | Control (n = 169), % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 75.7 ± 7.0 | 75.9 ± 7.9 | .83 |

| Score on 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 8.4 ± 2.4 | .39 |

| Male | 41 | 38 | .59 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American | 28 | 37 | .19 |

| White | 49 | 39 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 9 | 6 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 4 | |

| Other/unknown | 9 | 14 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 43 | 34 | .41 |

| Widowed | 33 | 35 | |

| Separated/divorced | 9 | 15 | |

| Never married | 8 | 8 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 8 | |

| Finished high school† | 87 | 76 | .04 |

| Income | |||

| <$10,000 | 3 | 14 | .002 |

| $10,000 –$19,999 | 23 | 27 | |

| $20,000 –$30,000 | 10 | 11 | |

| >$30,000 | 12 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 52 | 42 | |

| Employment† | |||

| Working (full-time or part-time) | 8 | 5 | .53 |

| Not working | 92 | 95 | |

| Current smoking† | 6 | 11 | .23 |

| Current problem drinking† | 2 | 1 | .48 |

| Fair/poor health† | 58 | 57 | .95 |

| Antidepressant use past 12 mo | 23 | 17 | .15 |

| Number of clinic visits past 12 mo | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | .08 |

| Hospitalized past 12 mo | 33 | 27 | .18 |

| Medical comorbidity score | 16.7 ± 16.3 | 18.7 ± 21.0 | .38 |

Plus-minus values are mean ± SD.

Data available for 206 (97 intervention and 109 control) participants.

We used logistic regression to determine whether the intervention was associated with physician diagnosis of depression, prescription of antidepressants, or depression (GDS ≥ 6 at follow-up), adding variables from Table 1 that were associated (at P < .10) with these outcomes. To identify potential confounding variables, we chose a less-stringent inclusion criterion (P < .10) for the logistic models (dichotomous outcomes) than for the generalized linear models (continuous outcomes). We also used repeated measures logistic regression to determine whether the intervention was associated with physician diagnosis, prescriptions for antidepressants, or depression as measured by the GDS at follow-up, adjusted to reflect any dependence within clinics due to the clustered randomization design. Analyses were performed with the use of Statistical Analysis Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

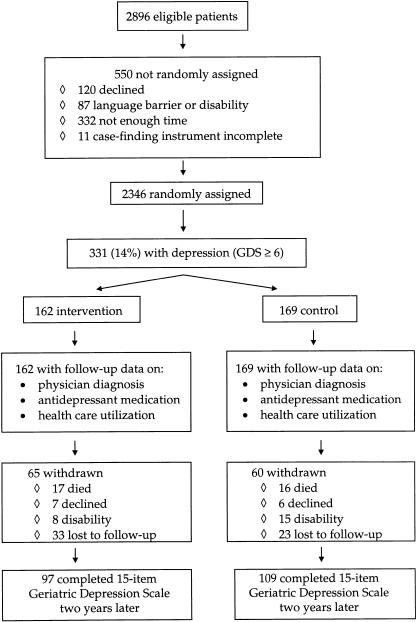

Of the 2,896 eligible patients, 120 declined to participate, 87 were unable to complete the GDS owing to a language barrier or physical disability (as assessed by the research assistant), 332 were missed because the research assistant did not have time to administer the GDS, and 11 did not complete the GDS successfully (Fig. 1). Of the 2,346 participants who successfully completed the GDS, 14.1% (331 of 2,346) had GDS scores suggestive of depression (GDS ≥ 6). These 331 participants (162 intervention and 169 control) are the subjects of this analysis. Participants in the intervention group were better educated and reported greater income than participants in the control group (Table 1). Only 12% of intervention group participants attended the educational group sessions.

FIGURE 1.

Profile of trial.

Diagnosis of Depression and Prescription for Antidepressant

During the 2-year follow-up period, 56 (35%) of the intervention participants and 58 (34%) of the control participants received a physician diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.0; CI, 0.6 to 1.6; P = .96). Of these participants, a total of 101 (91%) were identified by blinded review of ICD-9 codes from outpatient diagnosis forms and 13 (9%) were identified by follow-up telephone interview. Prescriptions for antidepressants were received by 59 (36%) of the intervention participants and 72 (43%) of the control participants (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.2; P = .3). These results were not changed when we used repeated measures logistic regression to adjust for possible dependence within clinics because of the clustered randomization design. Adjusting for baseline variables that were significantly different between the two groups (at P < .10) did not affect these results.

Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-up

Of the 331 participants, 33 (17 intervention and 16 control) died, 13 (7 intervention and 6 control) declined to complete the follow-up telephone interview, 23 (8 intervention and 15 control) were unable to complete the follow-up interview because of disability (e.g., severe dementia per proxy), and 56 (33 intervention and 23 control) were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1). Thus, 2-year follow-up for the GDS score was complete in 206 participants (69% of survivors). Participants who completed the follow-up GDS were more likely to be divorced or separated and had fewer clinic visits in the 12 months prior to randomization than those who did not complete the follow-up GDS, but we found no differences in initial mean GDS scores or other baseline variables between these groups.

A total of 42% (41 of 97) of the intervention participants and 50% (54 of 109) of the control participants had GDS scores suggestive of depression (GDS ≥ 6) at the 2-year follow-up (8% difference between groups, 95% CI, −6% to 21%) (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4 to 1.3; P = .30). When we repeated this analysis using repeated measures logistic regression to adjust for possible dependence within clinics, we found no effect of the intervention on depression at follow-up. Adjusting for baseline variables that were significantly different between the 2 groups (at P < .10) did not affect these results.

Mean GDS scores decreased over time for both intervention and control participants (P < .001 within each group). However, we did not find a significant difference between groups in mean GDS change scores at the 2-year follow-up (0.3 difference between groups, 95% CI, −0.7 to 1.4) (Table 2)), nor were there any differences in mean number of clinic visits (1.8 ± SD 3.1 vs 1.6 ± SD 2.8; P = .5) or number of hospitalizations (1.1 ± SD 1.6 vs 1.0 ± SD 1.4; P = .8) between intervention and control groups during the 2-year follow-up period.

Table 2.

Mean Change in Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Scores Between Baseline and Two-Year Follow-Up

| Variable | Intervention | n | Control | n | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (±SD) | |||||

| All participants | −2.4 ± 3.7 | 97 | −2.1 ± 3.6 | 109 | .50 |

| Initial GDS score ≥ 11 | −5.6 ± 3.9 | 13 | −3.4 ± 4.5 | 21 | .15 |

| Initial GDS score 6–10 | −1.9 ± 3.5 | 84 | −1.7 ± 3.3 | 88 | .75 |

| Multivariate adjusted (SE)* | |||||

| All participants | −1.8 (0.4) | 76 | −2.2 (0.4) | 97 | .41 |

| Initial GDS score ≥ 11 | −5.6 (1.2) | 13 | −3.4 (0.9) | 21 | .15 |

| Initial GDS score 6–10 | −1.6 (0.4) | 69 | −1.8 (0.4) | 76 | .70 |

Based on stepwise regression including all variables in Table 1. Variables associated with change in GDS score at P <.05 were included in the models: income, fair/poor health, and marital status were included in the model of all participants; no potential confounding variables were included in the model of participants with initial GDS score ≥ 11; income and fair/poor health were included in the model of participants with initial GDS score 6–10.

Timing of Notification

Among the subset (26%) of intervention participants whose physicians were informed of their GDS score before rather than after their appointments, we found no effect of the intervention on physician diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.7 to 1.7; P = .8), prescriptions for antidepressants (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.4; P = .5), or prevalence of depression (GDS ≥ 6) at the 2-year follow-up (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 1.2; P = .2), compared with all control participants.

Severe Depressive Symptoms

A total of 60 participants (24 intervention and 36 control) had severe depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 11) at baseline. Among these participants, a physician diagnosis of depression was recorded in 9 (38%) of the intervention participants and 11 (31%) of the control participants (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 0.5 to 4.1; P = .6). Prescriptions for antidepressants were received by 12 (50%) of the intervention participants and 17 (47%) of the control participants (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.4 to 3.1; P = .8). Among the 34 participants (13 intervention and 21 control) with severe depressive symptoms who completed the 2-year follow-up telephone interview, 8 (62%) in the intervention group and 14 (67%) in the control group had GDS scores suggestive of depression (GDS ≥ 6) (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.2 to 3.4; P = .8). There was a mean change in GDS score of −5.6 for intervention participants and −3.4 for control participants (Table 2). Although the intervention appeared to be associated with a greater decline in mean GDS scores among participants in this subgroup, we did not find a significant difference between intervention and control groups.

DISCUSSION

We found that informing primary care physicians about the results of a case-finding instrument for depression did not affect the frequency of depression diagnoses, prescriptions for antidepressant medications, the prevalence of depression, or health care utilization in elderly patients. Regardless of whether physicians were informed of patients' scores on the case-finding instrument for depression, approximately half of depressed elderly patients still had GDS scores suggestive of depression 2 years later.

Our findings support the results of 3 randomized trials8,9,12 and 4 observational studies.7,10,11,25 In one trial,8 physicians of patients in the intervention group were informed that their patients had high depression scores; physicians of patients in the control group were not so informed. In a second trial,9 physicians of intervention patients were given patient-specific treatment recommendations, and 3 special visits were scheduled to address the patients' symptoms of depression; control patients received usual care. Neither of these studies found any difference in mean depression scores at follow-up between intervention and control groups.

The third trial randomly assigned primary care patients to case-finding for depression versus usual care and found no difference between the groups in prevalence of depression at 3-month follow-up.12 Depressed patients who had been assigned to case-finding were more likely to recover than those who had been assigned to usual care, but after controlling for baseline severity of depression, the mean reduction in symptoms was similar for the case-finding and usual-care groups.

Four observational studies have found no difference in outcomes between depressed patients who were identified by their primary care physicians as depressed and those who were not recognized as depressed.7,10,11,25 The most recent of these studies reported that patients who were recognized by their primary care physician as depressed had better 3-month outcomes, but no difference in 12-month outcomes, compared with patients who were not recognized as being depressed.25

Given that effective treatments are available,26 why does case-finding for depression fail to improve patient outcomes? Even with enhanced detection, the majority of patients identified to have depression do not receive adequate dosage or duration of treatment in primary care settings.27–35 However, 3 clinical trials that randomly assigned depressed primary care patients to intensive intervention (e.g., increased frequency of visits and surveillance of medication adherence) versus usual care found that patients randomly assigned to the intervention showed significantly greater improvement in depression scores than patients randomly assigned to usual care.36–38 Perhaps more intensive programs such as the interventions applied in these trials will be needed to improve outcomes of depressed patients in the primary care setting.

An alternative explanation for why case-finding for depression does not affect patient outcomes is that primary care physicians may disregard the clinical significance of their patients' depression scores. We noted that only 12% of our intervention participants attended the educational group sessions. Although patient preferences must be considered, this sparse participation may reflect a lack of encouragement from primary care providers. Successful intervention programs for the treatment of depression will require the education of physicians, hiring of support staff, and streamlining of resources to help patients adhere to recommended therapies for depression.39

Another reason why providing the results of a case-finding instrument for depression to primary care physicians may not benefit patient outcomes is that many depressed primary care patients may have minimal impairment and improve regardless of treatment.40,41 Despite the functional morbidity associated with subsyndromal or minor depression,42–44 in which patients have fewer or less-debilitating symptoms than those required for major depression, only 1 of 4 randomized trials45 has demonstrated any benefit from therapy for these patients36,46,47

Although most case-finding instruments for depression have high sensitivity, all of them, including the GDS, are limited by low specificity for detecting depression.48,49 This means that approximately two thirds of patients who are identified by these instruments as being depressed will not have a clinical diagnosis of depression. Our study and 2 of the 3 previous randomized trials of case-finding for depression used symptom scales rather than a diagnostic interview for depression.8,9 However, the 1 trial that used an interview diagnosis of depression also found no benefit from case-finding.12

Our study has several limitations. First, if the intervention were associated with a transient improvement in depression, administering the GDS at 2-year follow-up may have missed this earlier benefit. Second, although we did not find a significant difference in GDS change scores between intervention and control groups (0.3 difference between groups; 95% CI, −0.7 to 1.4), our results are consistent with the possibility of a small benefit from the intervention on the prevalence of depression at follow-up among all participants (8% difference between groups; 95% CI, −6% to 21%). In addition, the change in GDS scores among participants with severe depressive symptoms suggests that this subgroup may have derived some benefit from the intervention. Our study would have needed a much larger sample size to determine whether the intervention was responsible for these results.

Third, we did not exclude patients with a prior diagnosis of depression or bipolar disorder, who may already have received any benefit conferred by early detection and recognition of depression. Fourth, patients who had physical disabilities or did not speak English were excluded from the study; thus, our results may not generalize to this population. Finally, although patient outcomes were determined in a blinded fashion, the participants and physicians in this study could not be blinded to the intervention.

In conclusion, we found that case-finding for depression did not improve outcomes in elderly primary care patients, although we could not exclude the possibility of benefit for a subgroup with severe depressive symptoms. It is unclear whether this lack of effect occurred because of spontaneous improvement in patients with undiagnosed depression, because of patient reluctance to undergo therapy, or because more intensive interventions are necessary to improve patient outcomes. Ongoing studies of improving quality of care for depression may clarify what other interventions must be combined with case-finding to benefit primary care patients with depression.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Whooley is supported by a Research Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service. This study was funded by a grant from the Garfield Memorial Fund.

We are indebted to Sondra Quiroz, Shiying Ling, and Li-Yung Lily Lui, MA, MS, for their assistance with data collection and analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care, Vol 1: Detection and Diagnosis. Clinical Practice Guideline. Washington, DC: AHCPR publication; 1993. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; pp. 93–0550. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The national depressive and manic-depressive association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277:333–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1796–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278:1186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Deeg DJ, Wallace RB. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whooley MA, Browner WS. Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in older women. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2129–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.19.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulberg HC, McClelland M, Gooding W. Six-month outcomes for medical patients with major depressive disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2:312–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02596165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowrick C, Buchan I. Twelve month outcome of depression in general practice: does detection or disclosure make a difference? BMJ. 1995;311:1274–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:839–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:99–105. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Simon GE. Occurrence, recognition, and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:636–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JW, Mulrow CD, Kroenke K, et al. Case-finding for depression in primary care: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 1999;106:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care. Ottawa, Ont: Canada Communication Group; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:709–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerety MB, Williams J, Jr, Mulrow CD, et al. Performance of case-findings tools for depression in the nursing home: influence of clinical and functional characteristics and selection of optimal threshold scores. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1103–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients: a comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:449–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. ICD-9-CM. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, Vol 1. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells KB, Burnam MA, Leake B, Robins LN. Agreement between face-to-face and telephone-administered versions of the depression section of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule. J Psychiatr Res. 1988;22:207–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon GE, Revicki D, VonKorff M. Telephone assessment of depression severity. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:247–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon GE, Goldberg D, Tiemens BG, Ustun TB. Outcomes of recognized and unrecognized depression in an international primary care study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Depression Guideline Panel. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Washington, DC: AHCPR publication; 1993. Depression in Primary Care, Vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression. Clinical Practice Guideline; pp. 93–0551. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J. Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care. 1992;30:67–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Barlow W. Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15:399–408. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon GE, Lin EHB, Katon W, et al. Outcomes of “ inadequate” antidepressant treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:663–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02602759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells KB, Katon W, Rogers B, Camp P. Use of minor tranquilizers and antidepressant medications by depressed outpatients: results from the medical outcomes study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:694–700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J. Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA. 1982;248:1848–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995;33:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Munoz RF, Ying YW. Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390170113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg L. Treating depression and anxiety in primary care: closing the gap between knowledge and practice. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1080–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan CM, Dittus RS, Tierney WM. Primary care physicians' medical decision making for late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:218–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02642478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice: eight-month clinical outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:913–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100061008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff. 1999;18:89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ormel J, Tiemens B. Recognition and treatment of mental illness in primary care: towards a better understanding of a multifaceted problem. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:160–4. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00022-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coyne JC, Schwenk TL, Fechner-Bates S. Nondetection of depression by primary care physicians reconsidered. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)00056-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck DA, Koenig HG. Minor depression: a review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:177–209. doi: 10.2190/AC30-P715-Y4TD-J7D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:694–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z, Caine ED. The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:647–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miranda J, Munoz R. Intervention for minor depression in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:136–41. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, Sedgwick P. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:971–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mulrow CD, Williams J, Jr, Gerety MB, Ramirez G, Montiel OM, Kerber C. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:913–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]