Abstract

BACKGROUND

Boundary violations have been discussed in the literature, but most studies report on physician transgressions of boundaries or sexual transgressions by patients. We studied the incidence of all types of boundary transgressions by patients and physicians' responses to these transgressions.

METHODS

We surveyed 1,000 members of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) for the number of patient transgressions of boundaries which had occurred in the previous year. Categories were created by the investigators based on the literature. Physicians picked the most important transgression, and then were asked about their response to the transgression and its effect on the patient-physician relationship. Attitudinal questions addressed the likelihood of discharging patients who transgressed boundaries. The impact of demographic variables on the incidence of transgressions was analyzed using analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Three hundred thirty (37.5%) randomly selected SGIM members responded to the survey. Almost three quarters of the respondents had patients who used their first name, while 43% encountered verbal abuse, 39% had patients who asked personal questions, 31% had patients who were overly affectionate, and 27% encountered patients who attempted to socialize. All other transgressions, including physical abuse and attempts at sexual contact, were uncommon. Only gender affected the incidence of transgressions; female physicians encountered more personal questions (P = .001), inappropriate affection (P < .005), and sexually explicit language (P < .05) than male physicians and responded more negatively to boundary transgressions. Respondents dealt with transgressions by discussion with the patient or colleagues or by ignoring the incident, but such transgressions generally had a negative impact on the relationship. Most physicians would discharge patients who engaged in physical abuse or attempts at sexual contact, but were more tolerant of verbal abuse and overly affectionate patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Boundary transgressions by patients is common, but usually involves more minor infractions. Female physicians are more likely to encounter certain types of transgressions. The incidence and outcomes of such transgressions are important in assisting physicians to deal effectively with this issue.

Keywords: boundary transgression, physician relationship

For most physicians, compassionate and empathetic care for their patients is balanced with professional distance and respect in the form of boundaries.1 Boundaries are mutually understood rules and roles which are found in relationships. It is clear, for example, that there is a strict proscription of sexual contact in the patient-physician relationship. Boundaries are important in situations where a power differential may exist.2 In the patient-physician relationship, they prevent exploitation of either of the two parties,3 by allowing the physician and patient to set appropriate limits during the interaction.

Cultural and sociodemographic aspects of the physician's and patient's family and peers, such as gender, ethnicity, age, and attitudes toward illness and death, play a major role in the formation of boundaries.4 However, underlying social and psychological development is most important in the formation of boundaries by individuals. Family-of-origin issues such as birth order and family role expectations may be key in how individuals form relationships.5 In dysfunctional families, boundaries are often either too diffuse or inflexible.6

When the rules of the patient-physician relationship are differently understood, unaccepted, or not respected, boundary transgressions can occur. While there has been a great deal of attention to transgressions of boundaries by physicians,1,7–9 less has been written about patient transgressions. However, such transgressions are known, especially in patients with borderline personality disorder10 and those patients with addictive personalities. Many borderline patients are unable to separate their fantasies from the reality around them,11 and especially under stress, these patients tend to transgress boundaries.10 Even patients without such severe psychopathology can sometimes lose sight of the well-established role and interpersonal boundaries in the patient-physician relationship. This can be especially prevalent at times of stress, when therapeutic touch can have inappropriate meanings for the patient.12 In addition, patients who are needy and unfulfilled may attempt to satisfy their needs from their interactions with physicians.13 The patient may then also become openly seductive of the physician.

Several studies have assessed boundary transgressions by patients involving sexual contact. In a study by Schulte and Kay,1471% of female medical students and 29% of male medical students reported that they had experienced at least one instance of patient-initiated sexual behavior during the course of their medical school years. Twelve percent of the female medical students indicated that there was sexual touching or grabbing by the patient. In another study, almost one third of practicing psychiatrists who had some sexual contact with their patients reported that the patient initiated the occurrence.15

Other transgressions of boundaries by patients may occur. Most studies have explored the more serious but uncommon types of boundary transgressions, such as verbal or physical abuse. For example, in a study of Canadian internists, more than 75% indicated they had experienced such abuse at least once by patients.16 Minor transgressions such as gift giving, sexual provocativeness, and the asking of personal questions of the physician have not been explored. Further, it is unclear whether there are sociodemographic characteristics of physicians which make such transgressions more likely to occur and how physicians respond to these transgressions. Therefore, we surveyed physicians about their experiences with patients who transgress boundaries in the patient-physician relationship.

METHODS

This study was designed as a cross-sectional mailed survey. A questionnaire was developed and pretested among a convenience sample of 25 participants of a workshop involving boundary transgressions. The instrument asked respondents how many times patients had transgressed boundaries involving 10 different categories (being overly affectionate; using sexually explicit language; attempting or engaging in sexual contact; attempting to socialize; using the physician's first name; attempting to give expensive gifts; asking personal questions of the physician; being verbally abusive; being physically abusive; and other) in the previous 12 months. The categories were developed by the investigators based on a review of the literature. The questionnaire then asked respondents to determine which incident had been most important to them and to mark that category as being the most important. Details about this incident were solicited, including how the physician handled the incident, whether a note about the incident was written in the chart, and whether the incident affected the patient-physician relationship on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = very positively to 5 = very negatively).

Physician respondents were asked a series of attitudinal questions, including the need to explore patients' psychological needs when they transgress boundaries, being angry with patients when they ask personal questions or use the physicians' first name, and whether the physician has an obligation to care for patients even if they transgress boundaries (all on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree). Questions were also included that asked about which patients should be discharged from the physician's practice based on boundary transgressions, which social invitations from patients respondents were willing to accept, and the maximum value of a gift the respondent was willing to accept from patients. Questions about personal and practice demographics were included.

After the instrument was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Christiana Care Health System, it was mailed to a nationwide sample of 1,000 randomly selected physician members of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) (associate members were excluded). A second questionnaire was mailed to all nonresponders 1 month after the initial mailing. All responses received before October 1, 1998 were included in the analysis. Respondents were assured that their responses would remain confidential and anonymous. The questionnaires contained no identifying information or code numbers; outside envelopes containing a code were received by a research assistant who immediately removed the response from the envelope, logged in the code number, and destroyed the envelope.

Data were entered for analysis manually by two individuals with a cross-check of 30% of the sample; there were no errors detected. The effects of demographic and practice variables on the reported number per year of various boundary transgressions and attitudinal questions were analyzed via univariate analyses of variance. A comparison of notes recorded in the chart for different transgressions of import to physicians was also analyzed via analysis of variance. The associations between the physicians' responses to the incident deemed most important and the effect of that incident on the patient-physician relationship was analyzed via χ2analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 1,000 surveys mailed, 112 were returned undelivered. Of the 888 surveys received by SGIM members, 333 (37.5%) were returned and complete. The demographic and practice characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1). Physician respondents had an average age of 43 years, and the majority were married, practiced in urban settings, and were involved in either an academic or academic/private practice environment. The average time spent seeing patients was about one half of the respondents' professional time. Overall, respondents were satisfied with their family and work environments.

Table 1.

Demographic and Practice Characteristics Transgressions of Boundaries by Patients*

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Mean age, y (SD) | 43 (7) |

| Gender, n(%) | |

| Male | 201 (61) |

| Female | 125 (38) |

| Marital status, n(%) | |

| Married | 289 (87) |

| Divorced | 15 (5) |

| Single | 15 (5) |

| Widowed | 3 (1) |

| Other† | 6 (2) |

| Practice locale, n(%) | |

| Urban | 250 (76) |

| Suburban | 59 (18) |

| Rural | 18 (5) |

| Practice type, n(%) | |

| Academic | 193 (58) |

| Private practice/academic | 40 (12) |

| VA | 22 (7) |

| Private practice | 20 (6) |

| HMO | 7 (2) |

| Other† | 46 (14) |

| Mean percentage (SD) of professional time seeing patients | 49 (27) |

| Satisfaction with work environment, n(%) | |

| Very satisfied | 140 (42) |

| Satisfied | 157 (48) |

| Unsatisfied | 28 (8) |

| Very unsatisfied | 3 (1) |

| Satisfaction with family life, n(%) | |

| Very satisfied | 239 (72) |

| Satisfied | 73 (22) |

| Unsatisfied | 14 (4) |

| Very unsatisfied | 1 (<1) |

Not all respondents answered every question. Percentage does not add up to 100 in all cases due to rounding and nonresponses.

Other includes hospital-based practices, freestanding clinics, etc.

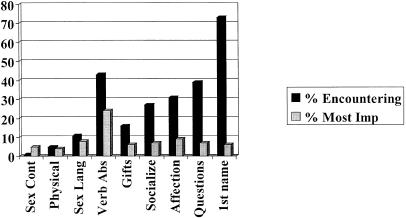

Due to the small number of occurrences of each boundary violation over the preceding 12-month period, the physicians' experiences with such transgressions are shown as the percentage of physicians who reported that a transgression occurred during that time period (Fig. 1). Serious transgressions such as physical abuse, sexual contact, and sexually explicit language were fairly uncommon. However, a number of less serious transgressions were encountered by a large percent of the responding physicians. There was a more even distribution of the most important incident as viewed by respondents; the exception was verbally abusive language, which was seen as the most important transgression by nearly one fourth of respondents. Only 37 (11%) respondents indicated that they had experienced no boundary transgressions in the preceding 12 months.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of respondent physicians indicating that they encountered various types of patient-initiated boundary transgressions in the previous 12 months, and the one which was deemed as most important to them. Sex cont indicates sexual contact; sex lang, sexual language; verb abs, verbal abuse.

As shown in Table 2, a note was written in the chart of the patient in a minority of the transgressions identified as most important by respondents, except for sexual contact with the physician and for verbally or physically abusive patients (P < .001); most respondents did write a note in the patient's chart for those incidents. Most respondents handled the transgression by discussing the incident with the patient (37%) or by talking with their colleagues (34%); however, 29% of respondents chose to ignore the most important transgression they encountered. An equal number of respondents felt the most important transgression affected the patient-physician relationship negatively or not at all, while a small minority felt that it had a positive influence on their relationship with the patient. Respondents who reported that the most important incident had a negative impact on their relationship with the patient were more likely to have discussed the incident with the patient, talked with colleagues about the incident, called for assistance in dealing with the patient, dismissed the patient from their practice, and were less likely to have ignored the incident than physicians who felt the incident had a negative or neutral effect on the patient-physician relationship (P < .001 for all).

Table 2.

The Most Important Boundary Transgression in the Previous 12 Months

| Response To Incident | |

|---|---|

| Note written in chart, n(%)* | |

| Overly affectionate patient | 6 (21) |

| Use of sexually explicit language | 7 (26) |

| Attempts to socialize with physician | 2 (9) |

| Use of physician's first name | 0 (0) |

| Giving of large/expensive gifts | 1 (5) |

| Asking physician personal questions | 4 (17) |

| Sexual contact with physician | 3 (50) |

| Verbally abusive patient | 63 (79) |

| Physically abusive patient | 10 (83) |

| How incident was handled, n(%)† | |

| Discussed with patient | 121 (37) |

| Talked with colleagues | 111 (34) |

| Ignored incident | 97 (29) |

| Dismissed from practice | 36 (11) |

| Called for assistance | 30 (9) |

| Other | 44 (13) |

| How incident affected patient-physician relationship, n(%) | |

| Very negatively | 37 (11) |

| Negatively | 93 (28) |

| Not at all | 122 (37) |

| Positively | 24 (7) |

| Very positively | 3 (2) |

| No answer | 51 (15) |

Physicians who wrote a note in chart as a percentage of the total number of physicians indicating each category as the most important boundary transgression encountered in previous 12 months.

Percentage adds up to more than 100 because physicians could choose all actions that applied.

Physician respondents agreed that physicians need to explore psychologic needs of patients who transgress boundaries and have an obligation to care for patients even when they violate boundaries in the patient-physician relationship (Table 3). Generally, they were not angry with patients who ask personal questions of physicians. However, the respondents did indicate some annoyance at patients who use the first name of the physician. The majority of physicians felt that a patient should be discharged from their practices for sexual contact with the physician (75%) and for physical abuse (88%); however, they were more tolerant of verbal abuse by patients (50% indicating the patient should be discharged from the practice) and of overt displays of affection by the patient (15% indicating that the patient should be discharged).

Table 3.

Opinions of Respondents About Patients Who Transgress Boundaries*

| Opinion | |

|---|---|

| Explore psychological needs, n(%) | |

| Strongly agree | 30 (9) |

| Agree | 169 (51) |

| Disagree | 110 (33) |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (3) |

| Obligation to care for patients, n(%) | |

| Strongly agree | 42 (13) |

| Agree | 168 (51) |

| Disagree | 90 (27) |

| Strongly disagree | 7 (2) |

| Angry about personal questions, n(%) | |

| Strongly agree | 3 (1) |

| Agree | 93 (28) |

| Disagree | 203 (62) |

| Strongly disagree | 25 (8) |

| Annoyed when first name used, n(%) | |

| Strongly agree | 39 (12) |

| Agree | 162 (49) |

| Disagree | 101 (31) |

| Strongly disagree | 19 (6) |

Not all respondents answered every question. Percentage does not add up to 100 in all cases due to rounding and nonresponses.

Two thirds of physician respondents reported that they would not accept invitations for socialization with patients. Slightly more than one tenth accepted invitations for dinner in the patient's home (12%) or lunch in the hospital cafeteria (13%), while only 9%, 6%, and 2% accepted lunch in a restaurant, dinner at a restaurant, or drinks at a bar, respectively. The mean value of a gift accepted by physician respondents was $23 (±$36).

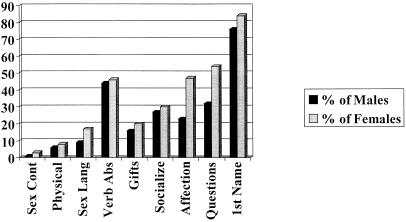

Of all of the sociodemographic and practice characteristics assessed, only gender impacted on the reported number of boundary transgressions in the previous 12 months and on opinions about boundary transgressions. As shown in Figure 2, female physicians reported significantly more boundary transgression in the prior 12 months for sexually explicit language (P < .05), personal questions (P = .001), and overly affectionate patients (P < .005). Female physicians were more likely to discharge patients from their practices than male physicians (P < .05,Table 4), were less tolerant than male physicians of patients who ask personal questions (P < .05) or used their first name (P < .01), and felt less strongly that they had an obligation to care for patients despite their transgressions of boundaries (P = .001). Because of the possibility that the greater number of transgressions seen by women physicians may have impacted on their responses to those transgressions, the effects of the types of boundary transgressions along with gender were analyzed via multiple logistic regression analyses. Only gender remained significant for the decision to discharge patients because of attempts at sexual contact (P = .027, R2 = .22), anger over the asking of personal questions (P = .05, R2 = .12), and the obligation to care for patients even when they transgress boundaries (P = .019, R2 = .35). For annoyance about being called by the physician's first name, gender (P = .01), the number of incidents of being called by the first name (P = .022), and the number of incidents of being asked personal questions (P = .001) affected physicians' responses (R2 = .092).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of percentage of male and female physician respondents who encountered different types of patient-initiated boundary transgressions in the previous 12 months. Sex cont indicates sexual contact; sex lang, sexual language; verb abs, verbal abuse.

Table 4.

Comparison of Male and Female Physician Respondents on Attitudes Regarding Patients Who Transgress Boundaries

| Attitude | |

|---|---|

| Discharge patients for sexual contact, n(%)* | |

| Male physicians | |

| Yes | 139 (69) |

| No | 61 (31) |

| Female physicians | |

| Yes | 108 (86) |

| No | 17 (14) |

| Angry about personal questions, n(%)* | |

| Male physicians | |

| Agree | 54 (27) |

| Disagree | 144 (73) |

| Female physicians | |

| Agree | 42 (34) |

| Disagree | 81 (66) |

| Annoyed when first name used, n(%)† | |

| Male physicians | |

| Agree | 113 (57) |

| Disagree | 84 (43) |

| Female physicians | |

| Agree | 87 (72) |

| Disagree | 34 (28) |

| Obligation to care for patients, n(%)‡ | |

| Male physicians | |

| Agree | 145 (74) |

| Disagree | 51 (26) |

| Female physicians | |

| Agree | 62 (57) |

| Disagree | 46 (43) |

P < .05.

P < .01.

P = .001.

DISCUSSION

Most of the respondent physicians in this study indicated that boundary transgressions by patients were not uncommon occurrences. While the more serious transgressions, such as sexual contact or explicit language use by patients, and physical abuse, were not frequent events. Less serious transgressions, such as verbal abuse, gift giving, attempts at socialization, overly affectionate behavior, asking personal questions, and using the first name of the physician, were noted by a significant percentage of respondents. However, there was an equal likelihood that the most troubling event in the previous 12 months was any of the boundary violations.

The transgression of interpersonal boundaries involving sexual behavior are often initiated by the patient. It is not surprising that the use of explicit sexual language was more common in our survey than was actual physical contact. In the study by Schulte and Kay,14 most of the occurrences took the form of sexual comments or requests for social meetings. However, 6 (12%) of 52 female medical students in this study reported that there was sexual touching or grabbing on the part of the patient. Thus, patients do occasionally transgress the interpersonal boundaries in the patient-physician relationship by engaging in or attempting to engage in sexual activity.

The verbal abuse seen in our study has also been reported elsewhere.16 This transgression was reported frequently by the physicians in our study and was clearly the most important event for the respondents. Physical abuse was reported less commonly, but was still an important event for the physician. Physical abuse was experienced by one third of physicians during their medical careers in 1 study (J. Morrison, personal communication). It is not surprising that 5% of the physicians who were surveyed in our study encountered this problem in the previous 12 months of practice.

Other boundary transgressions were more commonly reported by the physicians in this study. One of the occurrences was that of gift giving by the patient. Small gifts can sometimes be viewed as less serious boundary transgressions1; however, physicians need to be wary of repeated attempts to give gifts. We specifically inquired about larger or more expensive gifts, which are very clear and serious boundary transgressions. Repeated requests for socializing are also beyond the normal scope of the patient-physician relationship and constitute a transgression of boundaries. In our study, one quarter of the physicians encountered this type of transgression.

Another important issue in the patient-physician relationship is the use of language. A patient may call the physician by his/her first name while the physician uses the last name of the patient.17 This may occur due to a patient's wish for control of the relationship or envy of the physician. Although this was the most frequently encountered type of transgression (noted by three fourths of respondents), only a very few physicians noted this as the most important issue for them. A majority of respondents also indicated that they disagreed with the statement that they became annoyed when a patient used their first name. Similarly, while overly personal questions were encountered by almost 40% of respondents, only a few of the physicians were angered by the patients who transgress this boundary. Many physicians may not consider certain personal questions inappropriate.

Physicians must be able to effectively deal with patients who transgress boundaries in the patient-physician relationship. Strategies for dealing with patients who can occasionally become abusive or in other ways transgress boundaries include communicating clear expectations and setting limits with these patients.18 In this study, physicians clearly set limits with their patients in terms of socialization and the monetary value of gifts given by the patient. However, in addition to setting firm limits on the relationship, the physician must also acknowledge and address the patient's reasons for this attempt at a boundary transgression.14 Although a majority of the responding physicians indicated that they had an obligation to care for patients even when they transgress boundaries and should ask the patient why they felt compelled to initiate the boundary transgression, a significant portion of the respondents stated that they dealt with the most important transgression they encountered in the previous 12 months by ignoring the incident. Thus, a significant percent of the physicians who responded to the survey may have missed opportunities to prevent further boundary transgressions by discussing the issue with the patient.

It is not surprising that the female physicians in this study experienced more encounters with certain types of boundary violations by patients. In the study by Schulte and Kay,1471% of the female physicians completing the survey had experienced patient-initiated sexual behaviors during their careers, compared with only 29% of male physicians. Gender discrimination has also been shown to be more prevalent among female internists in Canada compared with their male counterparts.16 Perhaps because of the increased incidence and heightened awareness of such discrimination, the female physicians of this study seemed to be less tolerant of such behavior. This is reflected by their increased likelihood to discharge transgressors from their practices and increased annoyance with lesser transgressions.

This study has several limitations. The low response rate may introduce an element of nonresponse bias. However, 11% of respondents reported that they had not encountered any significant boundary transgressions in the previous 12 months. The more serious transgressions seen in this study such as sexual behaviors and physical abuse, while occurring at a low level, have been corroborated by other studies.14–16 In addition, the demographic characteristics of this study are fairly representative of the members of the SGIM as a whole. In the present study, average age of respondents was 43 years (79% of SGIM members are between the ages of 30 and 49), and 38% respondents were female, compared with 34% for SGIM members overall. This study also involved only academic general internists; therefore, its applicability to other physician groups may be questioned. We believe that physicians who see a greater number of patients have more frequent occurrences of patient-initiated boundary violations, thereby potentially increasing the problem for these physicians.

It is clear that many types of patient-initiated boundary transgressions are common and problematic for the practicing physician. Physicians may have opportunities to set limits with patients and ask patients about the reasons for these transgressions. In becoming aware of these occurrences, physicians can help maintain appropriate relationships with patients and possibly prevent future transgressions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gabbard GO, Nadelson C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1995;273:1445–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackshaw SL, Miller JB. Boundaries in clinical psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:293. Letter. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasburger LH, Jorgenson L, Sutherland P. The prevention of psychotherapist sexual misconduct: avoiding the slippery slope. Am J Psychotherapy. 1992;46:544–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1992.46.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinn WM. Doctors have feelings too. JAMA. 1988;259:3296–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Seaburn D. Family-oriented Primary Care. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 361–73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood B, Talmon M. Family boundaries in transition: a search for alternatives. Fam Proc. 1983;22:347–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1983.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, AMA. Sexual misconduct in the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1991;266:2741–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:188–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartrell NK, Milliken N, Goodson WH, Thiemann S, Lo B. Physician-patient sexual contact. Prevalence and problems. West J Med. 1992;157:139–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutheil TG. Borderline personality disorder, boundary violations, and patient-therapist sex: medicolegal pitfalls. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:597–602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon RI. Sexual exploitation of patients: how it begins before it happens. Psychiatr Ann. 1989;19:104–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehrman NS. Pleasure heals. The role of social pleasure—love in its broadest sense—in medical practice. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:929–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.153.8.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kardener SH. Sex and the physician-patient relationship. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1134–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulte HM, Kay J. Medical students' perceptions of patient-initiated sexual behavior. Acad Med. 1994;69:842–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gartrell N, Herman J, Olarte S, Feldstein M, Localio R. Psychiatrist-patient sexual contact: results of a national survey. I: Prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1126–31. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.9.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Cohen M, Guyatt GH, O'brien B. Discrimination and abuse experienced by general internists in Canada. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:565–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02640367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradshaw S, Burton P. Naming: a measure of relationships in a ward milieu. Bull Menninger Clin. 1976;40:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sparr LF, Rogers JL, Beahrs JO, Mazur DJ. Disruptive medical patients. Forensically informed decision-making. West J Med. 1992;156:501–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]