Abstract

Trichomonas vaginalis infection is highly prevalent worldwide and is associated with urethritis, prostatitis, and urethral strictures in men. However, the natural history and importance of T. vaginalis in men are poorly understood, in part because of difficulties in diagnosing infection. Traditional detection methods rely on culture and wet-mount microscopy, which can be insensitive and time consuming. Urethral swabs are commonly used to detect T. vaginalis in men, but discomfort from specimen collection is a barrier to large studies. One thousand two hundred twenty-five Malawian men attending sexually transmitted disease and dermatology clinics were enrolled in this cross-sectional study to validate detection by urine-based PCR-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with urine and urethral swab culture as the reference standard. This assay for detection of amplified T. vaginalis DNA in first-catch urine (≤30 ml) performed with a sensitivity of 92.7%, a specificity of 88.6%, and an adjusted specificity of 95.2% compared to culture of urethral swabs or urine sediment. For clinical research settings in which urethral swabs are not available and culture is not feasible, the urine-based PCR-ELISA may be useful for detection of trichomoniasis in men.

In men, trichomoniasis may be associated with urethritis (5, 11) and prostatitis (19). In addition, infection with Trichomonas vaginalis may increase human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission (2, 4). The estimated prevalence of trichomoniasis in men ranges from 0% in asymptomatic men (10, 27) to 58% in high-risk adolescents (21). Generally, however, the prevalence of trichomoniasis in men is estimated to be low (7-9). The reliability of prevalence estimates and an understanding of the natural history and sequelae of trichomoniasis in men are affected by difficulties in diagnosing trichomoniasis in men.

Detection of T. vaginalis in men has traditionally relied on wet-mount microscopy or culture of urine sediment or culture of urethral scrapings. These methods are highly specific but lack sensitivity. Collection of urethral material from men with a swab or loop is uncomfortable and may be a barrier to participation in research studies. Wet-mount microscopy of urine sediment requires a large organism burden for a positive result. Culture is more sensitive than wet preparation, but results may require 5 or more days of incubation. As a consequence of the time required for culture and the poor sensitivity of wet-mount microscopy, screening for T. vaginalis infection in men is infrequent or absent from standard practice at many clinics. Improved detection and treatment of T. vaginalis in men should reduce heterosexual transmission of the parasite to women and may impact HIV transmission.

The introduction of molecular amplification tests to detect Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in urine specimens has facilitated patient care and research studies of infections with these pathogens (1). These tests are more sensitive than culture, and the noninvasive nature of specimen collection has led to their widespread use. Several PCR assays have been developed to detect T. vaginalis in urine specimens from women (5, 12-14, 20, 24). However, detection of T. vaginalis in men by molecular amplification methods has received less attention. Urine-based PCR assays for men have been described (18, 22); however, formal validation of the assays has not been reported.

A useful nucleic acid amplification test for T. vaginalis detection would be applicable for both men and women and use specimens that could be self-collected noninvasively. We previously described a urine-based PCR combined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of T. vaginalis infection in women (5) and herein validate the assay for use with specimens from men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the context of a larger study of the prevalence and management of T. vaginalis infection in men. Subjects were enrolled between 27 January 2000 and 28 June 2001 from the sexually transmitted disease (STD) and dermatology outpatient clinics of Lilongwe Central Hospital, Lilongwe, Malawi. Men 18 years of age and older were eligible to participate if they provided written informed consent and agreed to come to follow-up visits for up to 5 weeks after enrollment. Eligible subjects enrolled through the STD clinic presented with symptoms of urethritis or genital ulcers; subjects enrolled through the dermatology clinic were asymptomatic with respect to STDs.

This study was approved by the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Malawi Ministry of Health. Consent forms were provided in both English and Chichewa, the local language.

Clinical data and specimen collection.

Medical history and behavioral data were collected for all study participants. The standardized questionnaire included questions about symptoms, sexual behavior, current medications, and symptoms of sexual partners. Questionnaires were administered by study staff in Chichewa.

Specimens were collected during a standardized clinical examination. Observations, diagnoses, and medications given were recorded on a standardized form. Blood was collected for HIV and syphilis serology tests. HIV testing was performed with the Capillus HIV-1/HIV-2 rapid test (Cambridge Diagnostics); positive results were confirmed by enzyme immunoassay (Genetic Systems HIV-1 peptide EIA; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Urethral swabs were collected for T. vaginalis culture and Gram staining. Urethritis was defined by the presence of four or more polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field in the Gram-stained specimen. Infection with N. gonorrhoeae was determined by the presence of gram-negative intracellular diplococci on the Gram stain. After the physical examination, subjects were requested to provide 20 to 30 ml of first-void urine in marked cups.

T. vaginalis culture.

Urethral swabs were immediately used to inoculate the TV InPouch culture system (Biomed, San Jose, Calif.). Urine specimens remained at room temperature and were processed within 4 h. For urine sediment cultures, 10 ml of first-void urine was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 × g at room temperature. The supernatant was aspirated, and 50 μl of sediment was used to inoculate the culture.

Cultures were incubated at 37°C in ambient atmosphere and examined for at least 1 min per sample by a trained microscopist on days 2 and 5 after inoculation. A recent positive T. vaginalis culture was maintained for comparison. Positive cultures contained parasites with characteristic morphology and motility. Motile trichomonads were absent from negative cultures at all readings. The combination of urine sediment culture and urethral swab culture served as the reference standard. Subjects with any positive culture were considered positive by the reference standard.

T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA.

Urine samples were processed at Lilongwe Central Hospital within 4 h of collection with the Amplicor CT Urine Specimen Prep Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.) or the Amplicor CT/NG Urine Specimen Prep Kit (Roche Applied Science), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Processed urine samples were frozen at −70°C until shipment in liquid nitrogen to the University of North Carolina for PCR.

A total of 1,225 urine specimens from men was tested with the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA. The first 1,028 urine specimens collected for this study were processed for PCR with the Amplicor CT Urine Specimen Prep Kit as described in Materials and Methods. This kit was discontinued by the manufacturer during the study, and the remaining 197 specimens were processed with the currently available Amplicor CT/NG Urine Specimen Prep Kit.

Preparations made in Malawi from specimens with the Amplicor CT Urine Specimen Prep Kit were frozen at −70°C and subsequently extracted with phenol and chloroform, and DNA was precipitated with 3 M ammonium acetate. Ten microliters of extracted preparations was used as the template in the PCR. Specimens processed in Malawi with the Amplicor CT/NG Urine Specimen Prep Kit did not require extraction. Fifty-microliter volumes of these samples were used as templates in the PCR. Under these conditions, the two urine preparation kits used in this study were equivalent.

The T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA was performed as previously described (5). Briefly, primers TVK3 and TVK7 (digoxigenin labeled) (6) were used to amplify T. vaginalis DNA specifically. Positive and negative controls were purified T. vaginalis DNA and sterile water, respectively. PCR products were detected with the PCR DIG ELISA detection kit (Roche Diagnostic Systems), the biotinylated TVK probe, and ELISA controls as described previously (5). Specimens and controls were tested in duplicate by ELISA. Tests were valid if the A405 was ≥2.0 for the PCR positive control, ≥1.0 for the ELISA positive control, and <0.2 for the negative control.

Standard measures were taken to ensure that specimens were not contaminated. Separate workspaces were maintained for specimen processing, PCR, and post-PCR work, and sterile, disposable laboratory supplies were used. The PCR primers (TVK3 and TVK7) were previously tested against a variety of sexually transmitted pathogens and other Trichomonas species and found to amplify only T. vaginalis DNA (6).

Data analysis.

Laboratory data were entered into databases created in Microsoft Excel 2000. Questionnaire and chart information was entered into databases created in EpiInfo version 6.04 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.). All data were double entered by different personnel. Discrepancies in data entry were resolved by review of chart and laboratory form information. Data analysis was performed with SAS version 7 (SAS institute, Cary, N.C.) and STATA version 7 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.).

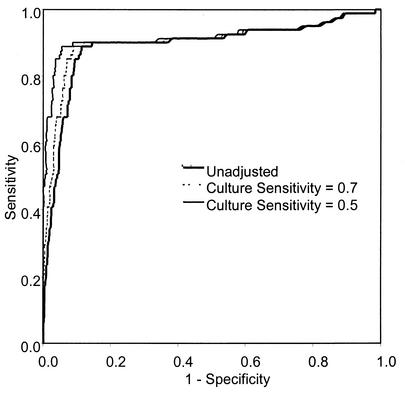

Estimates of the sensitivity and specificity of the test and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by standard methods. Nonparametric receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed by plotting sensitivity versus 1 − specificity at every possible cutoff point along the range of absorbances read. The absorbance value corresponding to the upper leftmost point is the cutoff point at which sensitivity and specificity are jointly maximized.

T. vaginalis culture is insensitive, and culture of specimens from men is generally less sensitive than that of specimens from women. The imperfect sensitivity of culture results in biased estimates of the specificity of the new test. We assessed the impact of reference test bias by adjusting the estimate of specificity with the formula of Staquet et al. (23) with a high (0.7) and a low (0.5) estimate of the sensitivity of T. vaginalis culture for men. The high and low estimates were based on the assumption used previously to validate the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA for women (5) and the observation that parasite growth in cultures from men is less vigorous than in cultures from women (our unpublished observations). We assumed that the reference standard and PCR tests are independent and that the specificity of the reference standard is 1.0. Under these conditions, the sensitivity estimate of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA is unbiased (23).

Urine culture, urethral swab culture, and the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA were compared to each other by latent-class analysis. This method uses the results of three or more tests to determine the sensitivity and specificity of each on the basis of the probability of a positive result from any one test (25, 26). Latent-class analysis assumes the independence of each test and was performed with software provided by S. Walter (25, 26).

RESULTS

Patient population.

During the study period, 1,361 male subjects were enrolled, 929 through the STD clinic and 432 through the dermatology clinic. Complete data and specimens were available for 1,225 study subjects. The ages of study participants ranged from 18 to 61 years, with a mean of 26.1 years (Table 1). Almost half (43.1%) of the study subjects were married at the time of enrollment. Most (77.7%) reported current employment. Seventy-eight percent of subjects reported fewer than 2 sexual partners in the previous 4 weeks, with a range of 0 to 30 partners.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age rangeb | |

| 18-22 | 380 (31.0) |

| 23-27 | 460 (37.5) |

| 28-32 | 232 (18.9) |

| 33-37 | 83 (6.8) |

| 38-42 | 46 (3.8) |

| >42 | 24 (2.0) |

| Total (mean) | 18-61 (26.1) |

| Married | 528 (43.1) |

| Current employment | 952 (77.7) |

| No. of sex partners in previous 4 weeks | |

| 0 | 273 (22.3) |

| 1 | 687 (56.1) |

| 2 | 188 (15.3) |

| 3 or more | 64 (5.2) |

Total, 1,225.

Age ranges are given in years.

Common signs and symptoms in the STD clinic were urethral discharge, genital ulcer disease, dysuria, and urethritis (Table 2). HIV was diagnosed in 46.7% of STD clinic subjects (n = 434) and 27.6% of dermatology clinic subjects (n = 119). The 136 subjects (10% of the study population) for whom complete data and specimens were not available were similar to the rest of the study population in demographics and clinical characteristics (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of enrolled subjects

| Characteristic | No. (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| All subjects (n = 1,361) | STD clinic subjects (n = 929) | |

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Complaint of urethral discharge | 515 (37.9) | 515 (55.5) |

| Genital ulcer diseasea | 534 (39.3) | 533 (57.4) |

| Dysuria | 623 (45.8) | 591 (63.6) |

| Observed urethral discharge | 530 (38.9) | 530 (57.1) |

| Urethritisb | 593 (43.6) | 568 (61.1) |

| STDsc | ||

| T. vaginalis infection | 98 (7.2) | 84 (9.1) |

| N. gonorrhoeae infection | 407 (30.0) | 406 (43.8) |

| HIV infection | 553 (40.6) | 434 (46.7) |

As observed by a clinician.

Four or more polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field.

T. vaginalis infection was diagnosed by culture, N. gonorrhoeae infection was diagnosed by Gram staining of urethral material, and HIV infection was diagnosed by Capillus HIV-1/HIV-2 rapid test and confirmed by enzyme immunoassay.

T. vaginalis was detected by culture of urethral swab or urine sediment in 9.0% (n = 84) of the study subjects enrolled through the STD clinic and 3.2% (n = 14) of the subjects from the dermatology clinic. The prevalence of culture-proven T. vaginalis among HIV-positive subjects was 6.7% (n = 53), and among HIV-negative subjects, it was 8.1% (n = 45). Trichomoniasis was more common among men with urethritis (9.6%; n = 57) than among men without urethritis (5.4%; n = 41).

Performance of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA.

To determine an appropriate absorbance cutoff value for the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA of urine from men, a ROC curve was constructed as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1). The area under the unadjusted curve was 0.891 (standard error = 0.025), indicating a high degree of overall accuracy of the test. At an absorbance cutoff of 2.0, the urine PCR performed with 88.9% sensitivity (95% CI, 79.2 to 94.4) and an unadjusted specificity of 88.6% (95% CI, 86.8 to 90.4) compared to culture. Raising the A405 cutoff to 3.0 reduced the sensitivity to 86.3% (95% CI, 76.3 to 92.6) and increased the specificity to 90.3% (95% CI, 88.4 to 91.9). To maximize sensitivity, we chose an absorbance cutoff value of 2.0.

FIG. 1.

ROC analysis of PCR-ELISA for detection of T. vaginalis in men's urine. ROC curves were plotted for the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA, and specificity was adjusted by assigning the reference standard sensitivities of 50 and 70%.

T. vaginalis culture is recognized as imperfectly sensitive and virtually 100% specific. With culture as the reference standard, the specificity of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA will be underestimated. To compensate for this reference test bias, we adjusted the specificity estimate algebraically by the method of Staquet et al. (23) with a high (70%) and a low (50%) estimate for the sensitivity of T. vaginalis culture for men. The effects of the specificity adjustments on the ROC curve are shown in Fig. 1. At an absorbance cutoff of 2.0, the adjusted specificities of the urine PCR were 91.0 and 94.5% for the high and low culture estimates, respectively.

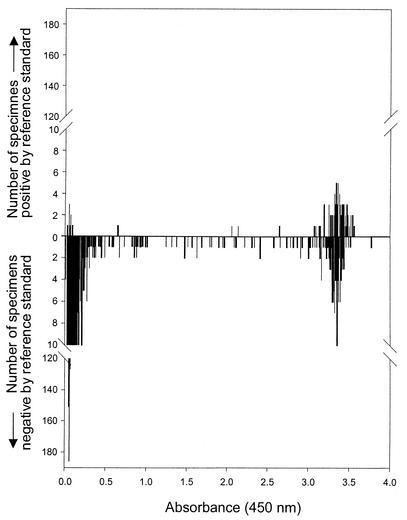

The ROC curves display an early deviation from the vertical axis, indicating that the specificity of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA falls off rapidly. This portion of the curve corresponds to very high absorbance cutoff values. Such a shape is consistent with the possible misclassification of truly positive specimens as false positives. To examine the performance of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA further, we graphed the results for each specimen according to its absorbance from the ELISA and the corresponding result of the combined reference standard (Fig. 2). The histograms had two distinct peaks, one at absorbances of <0.5 and one at absorbances of >3.0. Most of the culture-negative specimens had correspondingly low absorbances, and the majority of culture-positive specimens had very high absorbances. However, 64% of the specimens with absorbances of >2.0 were negative for T. vaginalis by culture. There were few specimens with absorbances between the lower peak and the cutoff point of 2.0, i.e., only 3.4% (n = 40) of the culture-negative specimens and 1.2% (n = 1) of the culture-positive specimens. The two distinct peaks with few observations located between them suggest that many specimens with absorbances above the cutoff point may represent infections with T. vaginalis despite negative culture results.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of ELISA absorbance values for T. vaginalis PCR assay of men's urine. Histograms show data for men who were positive (top) or negative (bottom) by the reference standard of urine sediment culture and urethral swab culture.

Effect of specimen processing.

Because the urine preparation method changed during the course of the study, we assessed the performance of the assay with each method separately. The sensitivity of the assay with specimens processed with the discontinued kit was slightly higher (89.0%), and the adjusted specificity was slightly lower (94.3%), than that of the assay with specimens processed with the currently available kit (sensitivity, 85.7%; adjusted specificity, 96.2%).

Effects of clinical factors and specimen volume.

We compared the performance of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA with samples from subjects with different clinical characteristics. The test performed with comparable sensitivity and specificity for subjects with or without urethritis (four or more polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field), urethral discharge, genital ulcers, or concomitant STDs (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Performance of T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA with subpopulations and with specimens with different clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | No. of subjects | % Sensitivity (95% CI) | % Specificity (95% CI) | Adjusted % specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urethritisa | ||||

| Present | 521 | 87.2 (73.6-94.7) | 89.0 (85.8-91.6) | 97.5 |

| Absent | 701 | 90.9 (74.5-97.6) | 88.5 (85.7-90.7) | 92.7 |

| HIV | ||||

| Positive | 496 | 84.6 (68.8-93.6) | 86.9 (83.3-89.8) | 93.5 |

| Negative | 711 | 92.7 (79.0-98.1) | 89.7 (87.1-91.8) | 95.1 |

| N. gonorrhoeaeb | ||||

| Positive | 364 | 85.0 (61.1-96.0) | 89.5 (85.7-92.5) | 94.1 |

| Negative | 858 | 90.0 (78.8-95.9) | 88.3 (85.9-90.4) | 94.7 |

| Dysuria | ||||

| Present | 554 | 86.8 (71.1-95.1) | 89.7 (86.7-92.1) | 95.8 |

| Absent | 671 | 90.5 (76.5-96.9) | 87.8 (84.9-90.2) | 93.4 |

| Urethral dischargec | ||||

| Present | 464 | 87.9 (70.9-96.0) | 90.3 (87.0-92.8) | 96.7 |

| Absent | 761 | 89.4 (76.1-96.0) | 87.7 (85.0-90.0) | 93.1 |

| Urine volume | ||||

| >30 ml | 646 | 84.2 (68.1-93.4) | 89.0 (86.2-91.3) | 93.7 |

| ≤30 ml | 559 | 92.7 (79.0-98.1) | 88.2 (85.1-90.8) | 95.2 |

Four or more polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field.

Infection based on presence of gram-negative intracellular diplococci on Gram staining.

As observed by a clinician on physical examination.

The volume of urine collected was predicted to affect the performance of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA. With larger specimen volumes, the expected concentration of organisms in urine is lower. Although subjects were instructed to collect the first 20 to 30 ml of first-void urine, many specimens exceeded these limits. Urine volumes ranged from 2 to 80 (mean, 32.7) ml. The T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA was slightly, but not significantly, more sensitive, and its adjusted specificity was higher, with specimens of 30 ml or less than with specimens of larger volumes (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study validates the use of PCR-based detection of T. vaginalis in urine samples from men. We observed an overall sensitivity of 88.8% and an adjusted specificity of 94.5% compared to culture of urine sediment and urethral swabs. In specimens that met the volume requirements, the test performed with 92.7% sensitivity and 95.2% adjusted specificity. We previously reported a validation study of a PCR assay for detection of T. vaginalis in urethral swabs from men with 81.6% sensitivity and 97.9% specificity (4). The current T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA had a higher sensitivity and a lower specificity than the previously validated PCR method. The two assays used the same primers and similar PCR methods. However, the previously validated test used gel electrophoresis to detect amplified PCR products. ELISA detection of amplified sequences is more sensitive than gel electrophoresis (5) and may explain the greater sensitivity of the assay described here. The higher sensitivity would also increase the number of infections missed by culture alone, thus increasing the false-positive fraction and lowering the observed specificity.

The choice of reference test is crucial for the evaluation of any new testing method. Culture is currently considered the best method by which to diagnose trichomoniasis. We chose to combine the results of two acceptable culture specimens. Urethral swab specimens are reported to be the most sensitive single specimens for culture of T. vaginalis in men, followed by urine sediment (7). Men can harbor T. vaginalis at multiple sites in the reproductive tract, and frequently organisms may be found in one specimen but not in another from the same individual (reference 7 and our unpublished observations). Because we hypothesized that PCR would be more sensitive than culture, we designed the reference test to maximize its sensitivity. In this study, the sensitivity of the reference standard was increased by 51% over that of urethral swab culture alone by inclusion of urine sediment culture.

Although urethral swabs are frequently considered the most sensitive specimens for T. vaginalis detection in men, addition of urine testing to increase sensitivity has been suggested (9). If we had also tested urethral swab specimens with the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA, the sensitivity and specificity of the assay might have improved. Testing of either urine or urethral swabs, but not both, would result in some missed cases of disease, and the two types of specimen may result in equal sensitivity (S. C. Kaydos, M. M. Hobbs, M. A. Price, et al., Abstr. Int. Congr. Sex. Transm. Infect., p. 38, 2001). However, collection of urethral swabs is an invasive procedure, is uncomfortable for patients, requires a clinic visit, and is impractical for large, population-based studies. The addition of a urine-based screening test for T. vaginalis would complement routinely used similar tests for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. In addition, the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA has been validated for testing of samples from women (5), and uniform collection and processing procedures for men and women should increase the utility of the test.

Discrepant analysis has been used in other validation studies of PCR assays for detection of T. vaginalis (14, 20). To avoid the sensitivity and specificity biases that can occur as a result of discrepant analysis (3, 15-17), we used an algebraic method to decrease reference test bias (23). Part of the adjustment for specificity requires assignment of the sensitivity of the reference standard, and it is important to estimate this value accurately. We compared test performance by assigning a value of 50 or 70% sensitivity to the reference test. In our previous study with samples from women, the sensitivity of a combined reference standard using wet-mount microscopy and culture of vaginal fluids was estimated to be 70% (5). The assumption that the combination of urethral swab culture and urine sediment culture for men is as sensitive as vaginal swab culture and wet-mount microscopy for women was explored for comparison. However, several observations suggest that the reference standard may be even less sensitive for men than for women. The T. vaginalis organism burden appears to be lower in men than in women, and cultures do not thrive as well as those of clinical isolates from women (our unpublished observations). In our experience, within 1 or 2 days of collection, the great majority of positive cultures from females teem with trichomonads whereas cultures from men frequently have only a few trichomonads and the numbers often do not increase over the culture period (unpublished observations). Thus, the assumption of 50% sensitivity of the reference standard in this study is reasonable and should not result in an overestimate of the specificity of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA.

Despite algebraic adjustment, the performance of the T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA may still be affected by reference test bias. Reference test-positive specimens generally had high absorbances in the ELISA (Fig. 2). There are two peaks of reference test-negative specimens on the histogram, one between 0.000 and 0.500 and one between 3.000 and 3.600. Raising the cutoff point for the ELISA would have increased the specificity of the test only slightly. The ROC curve with early deviation from the vertical axis and the shape of the histogram (Fig. 2), two peaks with very few specimens between them, suggest that many of the specimens in the second peak represent trichomoniasis cases that were not detected by the reference standard test. This result is unavoidable when comparing a highly sensitive detection method to a less sensitive reference standard.

The urine-based T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA was designed for use in large-scale studies of STDs involving men and women and was therefore simplified where possible. In the present study, specimens were processed on the day of collection. However, the previous study with samples from women demonstrated similar sensitivity and specificity for urine specimens that were stored at 4°C for up to 4 days (5). The T. vaginalis PCR-ELISA compared favorably to urine sediment culture and urethral swab culture, both of which are prohibitively time consuming and logistically difficult for large studies. The use of a commercially available kit to process urine facilitates work that must be performed in the field or in modestly equipped laboratories. This method should facilitate the detection of trichomoniasis, which may increase our knowledge of the epidemiology and natural history of T. vaginalis infection in men and their female partners.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 DK049381, NIH Sexually Transmitted Disease Cooperative Research Centers grant U01 AI31496, NIH Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinical Trials Unit contract N01 AI75329, and NIH National Study of Adolescent Health: Survey 2000 grant P01 HD31921. W.C.M. received support through the Clinical Associate Physician Program of the General Clinical Research Center (RR00046), Division of Research Resources, NIH. S.C.K.D. received support from NIH training grant T32 AI007001.

We thank Jimmy Malanda, Jones Mhango, Kondwani Banda, Andrew Agabu, Tchangani Tembo, Esnath Msowoya, Ester Kip, Nora Chilembwe, and Astrid Phale of the UNC Project in Lilongwe, Malawi, for enrollment and specimen collection and Seveliano Phakati, David Namhakwa, and Syze Gama for specimen processing. Peter Kazembe of Lilongwe Central Hospital aided us with administrative issues. Matthew Price, Shannon Galvin, and Karen Sweeney of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were instrumental in supervising the study in Malawi. We thank Rob Krysiak for the shipment of supplies and Jay Gratz for providing excellent laboratory assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carroll, K. C., W. E. Aldeen, M. Morrison, R. Anderson, D. Lee, and S. Mottice. 1998. Evaluation of the Abbott LCx ligase chain reaction assay for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine and genital swab specimens from a sexually transmitted disease clinic population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1630-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen, M. S. 1998. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: no longer a hypothesis. Lancet 351(Suppl. III):5-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadgu, A. 1996. The discrepancy in discrepant analysis. Lancet 348:592-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobbs, M. M., P. Kazembe, A. W. Reed, W. C. Miller, E. Nkata, D. Zimba, C. C. Daly, H. Chakraborty, M. S. Cohen, and I. Hoffman. 1999. Trichomonas vaginalis as a cause of urethritis in Malawian men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 26:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaydos, S. C., H. Swygard, S. L. Wise, A. C. Sena, P. A. Leone, W. C. Miller, M. S. Cohen, and M. M. Hobbs. 2002. Development and validation of a PCR-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with urine for use in clinical research settings to detect Trichomonas vaginalis in women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:89-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kengne, P., F. Veas, N. Vidal, J. L. Rey, and G. Cuny. 1994. Trichomonas vaginalis: repeated DNA target for highly sensitive and specific polymerase chain reaction diagnosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 40:819-831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger, J. N. 1995. Trichomoniasis in men: old issues and new data. Sex. Transm. Dis. 22:83-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger, J. N., and J. F. Alderete. 2000. Trichomonas vaginalis and trichomoniasis, p. 587-604. In K. K. Holmes, W. Stamm, E. W. Hook III, and W. Cates, Jr. (ed.), Sexually transmitted diseases. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Krieger, J. N., M. Verdon, N. Siegel, C. Critchlow, and K. K. Holmes. 1992. Risk assessment and laboratory diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1362-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuberski, T. 1978. Evaluation of the indirect technique for study of Trichomonas vaginalis infections, particularly in men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 5:97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latif, A. S., P. R. Mason, and E. Marowa. 1987. Urethral trichomoniasis in men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 14:9-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawing, L. F., S. R. Hedges, and J. R. Schwebke. 2000. Detection of trichomonosis in vaginal and urine specimens from women by culture and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3585-3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madico, G., T. C. Quinn, A. Rompalo, K. T. McKee, Jr., and C. A. Gaydos. 1998. Diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection by PCR using vaginal swab samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3205-3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayta, H., R. H. Gilman, M. M. Calderon, A. Gottlieb, G. Soto, I. Tuero, S. Sanchez, and A. Vivar. 2000. 18S ribosomal DNA-based PCR for diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2683-2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAdam, A. J. 2000. Discrepant analysis: how can we test a test? J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2027-2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, W. C. 1998. Bias in discrepant analysis: when two wrongs don't make a right. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51:219-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, W. C. 1998. Can we do better than discrepant analysis for new diagnostic test evaluation? Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:1186-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morency, P., M. J. Dubois, G. Gresenguet, E. Frost, B. Masse, S. Deslandes, P. Somse, A. Samory, F. Mberyo-Yaah, and J. Pepin. 2001. Aetiology of urethral discharge in Bangui, Central African Republic. Sex. Transm. Infect. 77:125-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkawa, M., K. Yamaguchi, S. Tokunaga, T. Nakashima, and F. Shinichi. 1992. The incidence of Trichomonas vaginalis in chronic prostatitis patients determined by culture using a newly modified liquid medium. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1205-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterson, B. A., S. N. Tabrizi, S. M. Garland, C. K. Fairley, and F. J. Bowden. 1998. The tampon test for trichomoniasis: a comparison between conventional methods and a polymerase chain reaction for Trichomonas vaginalis in women. Sex. Transm. Infect. 74:136-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena, S. B., and R. R. Jenkins. 1991. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis in men at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases. Sex. Transm. Dis. 18:138-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwebke, J. R., and L. F. Lawing. 2002. Improved detection by DNA amplification of Trichomonas vaginalis in males. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3681-3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staquet, M., M. Rozencweig, Y. J. Lee, and F. M. Muggia. 1981. Methodology for the assessment of new dichotomous diagnostic tests. J. Chronic Dis. 34:599-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Schee, C., A. van Belkum, L. Zwijgers, E. van der Brugge, L. O'Neill, E., A. Luijendijk, T. van Rijsoort-Vos, W. I. van der Meijden, H. Verbrugh, and H. J. Sluiters. 1999. Improved diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection by PCR using vaginal swabs and urine specimens compared to diagnosis by wet mount microscopy, culture, and fluorescent staining. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:4127-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter, S. D., D. J. Frommer, and R. J. Cook. 1991. The estimation of sensitivity and specificity in colorectal cancer screening methods. Cancer Detect. Prev. 15:465-469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter, S. D., and L. M. Irwig. 1988. Estimation of test error rates, disease prevalence and relative risk from misclassified data: a review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 41:923-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whittington, M. J. 1957. Epidemiology of infections with Trichomonas vaginalis in the light of improved diagnostic methods. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 33:80-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]