Abstract

The NCCLS M38-A document does not describe guidelines for testing caspofungin acetate (MK-0991) and other echinocandins against molds. This study evaluated the susceptibilities of 200 isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus, A. nidulans, A. niger, and A. terreus to caspofungin (MICs and minimum effective concentrations [MECs]) by using standard RPMI 1640 (RPMI) and antibiotic medium 3 (M3), two inoculum sizes (103 and 104 CFU/ml), and two MIC determination criteria (complete [MICs-0] and prominent growth inhibition [MICs-2]) at 24 and 48 h. Etest MICs were also determined. In general, caspofungin MIC-2 and MEC pairs were comparable with both media and inocula (geometric mean ranges of MECs and MICs, respectively, with larger inoculum: 0.12 to 0.64 μg/ml and 0.12 to 0.44 μg/ml with RPMI versus 0.04 to 0.51 μg/ml and 0.03 to 0.21 μg/ml with M3); however, MEC results were less influenced by testing conditions than MICs, especially with the larger inoculum. Overall, the agreement between caspofungin Etest MICs and broth dilution values was higher with MECs obtained with M3 (>90%) and the large inoculum than under the other testing conditions. Because RPMI is a more stable and chemically defined medium than M3, the determination at 24 h of the easier visual MECs with RPMI and the inoculum recommended in the M38-A document appears to be a suitable procedure at present for in vitro testing of caspofungin against Aspergillus spp. Future in vitro correlations with in vivo outcome of both microdilution and Etest procedures may detect more-relevant testing conditions.

Although Aspergillus fumigatus is responsible for the majority (85 to 90%) of the different clinical manifestations of mycoses, other Aspergillus spp. have been associated with severe infections in the immunocompromised host (20, 21, 23, 33, 36). In response to the emergence of resistance to reference agents (8, 9, 16, 34), several antifungal agents are undergoing clinical trials prior to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. Among them, caspofungin acetate (MK-0991) is a new echinocandin that has been recently approved for the treatment of refractory aspergillosis and has in vivo activity in experimental aspergillosis, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis (1, 2, 18, 19). With the increased incidence of fungal infections, the emergence of resistance to established agents, and the growing number of new antifungal agents, the laboratory role in the selection and monitoring of antifungal therapy has gained greater attention. The National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Tests has developed reproducible broth macro- and microdilution standard procedures (NCCLS M38-A document) for the antifungal susceptibility testing of opportunistic filamentous fungi (molds) (26). These parameters include the determination of MICs after 48 h of incubation at 35°C by using standard RPMI 1640 (RPMI) and an inoculum size of approximately 104 CFU/ml (26). Since caspofungin and other echinocandins have different mechanisms of action than those of triazoles and amphotericin B, are NCCLS testing guidelines the best means to evaluate the susceptibility of Aspergillus spp.?

It has been reported that the detection of morphological alterations of the hyphal cells, defined as the minimum effective concentration (MEC) by Kurtz et al. (22), is a more appropriate in vitro susceptibility end point for echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin) than the conventional MIC. Agar diffusion methods, especially Etest, also have been evaluated for testing new and reference agents against yeasts and molds and caspofungin against yeasts (5, 12, 13, 25, 29-32, 35). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the variability of different broth microdilution susceptibility testing conditions for the determination of caspofungin MICs and MECs for 200 isolates of five species of Aspergillus. In addition, these broth microdilution values were compared to Etest MICs for a subset of 169 isolates. MICs of amphotericin B and itraconazole were also obtained by the NCCLS broth microdilution M38-A method (26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Each isolate was tested with itraconazole and amphotericin B by following the NCCLS susceptibility testing guidelines for molds (26). In addition, each isolate was tested with caspofungin by the NCCLS microdilution method (26) and by other susceptibility testing conditions to be evaluated: (i) two medium formulations (RPMI and antibiotic medium 3 [M3]); (ii) two inoculum sizes (103 and 104 CFU/ml); (iii) two incubation times (24 and 48 h); (iv) two criteria of MIC determination (100% and ≥50% growth inhibition); (v) the determination of microscopic and visual MECs after 24 h of incubation; and (vi) the determination of Etest MICs at 24 and 48 h. The objectives of this study were (i) to evaluate the variability of the broth microdilution test when two medium formulations, inoculum sizes, incubation times, and criteria of MIC determination were examined; (ii) to compare MICs with MEC values obtained under the testing conditions listed above; and (iii) to compare MIC and MEC results obtained under each set of broth dilution testing conditions with MICs obtained by the agar diffusion Etest method.

Isolates.

The set of isolates included 22 Aspergillus flavus isolates, 137 A. fumigatus isolates (including 3 itraconazole-resistant and 1 voriconazole-resistant laboratory mutant isolates), 13 A. nidulans isolates, 13 A. niger isolates, and 15 A. terreus isolates. Each isolate was received at the Medical College of Virginia Campus for MIC testing during the last 4 years and was maintained at −70°C until testing was performed. The NCCLS quality control (QC) isolate Candida krusei ATCC 6258 (27) and reference isolates A. flavus ATCC 204304, A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 (26), and A. fumigatus ATCC 13070 were included as controls (4, 14, 26, 27).

Broth microdilution susceptibility testing. (i) Media.

The standard RPMI (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) contained 0.2% dextrose, 0.3 g of l-glutamine per liter, and 0.165 M MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer (34.54 g/liter) to a pH (mean ± standard deviation) of 7.0 ± 0.01 at 35°C; it did not contain sodium bicarbonate. The M3 broth was prepared following the instructions of the manufacturer (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), and the pH was 7.0 ± 0.05. Amphotericin B and itraconazole MICs were obtained using only the standard RPMI; caspofungin MICs and MECs were determined by using both RPMI and M3 broths.

(ii) Antifungal agents and drug concentrations.

Itraconazole (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Titusville, N.J.), amphotericin B (E. R. Squibb & Sons, Princeton, N.J.), and caspofungin (Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, N.J.) were provided from their manufacturers as standard powders. Additive drug dilutions of itraconazole and amphotericin B were prepared at two times the final strength required for the test (8 to 0.007 μg/ml) in RPMI (26). Caspofungin was prepared in each of the two media to obtain two times the final concentrations (8 to 0.007 μg/ml). The diluted concentrations were dispensed into the wells of 96 microdilution trays (U-shaped wells) in 100-μl volumes; the trays were stored at −70°C until they were needed.

(iii) Inoculum preparation.

Stock inoculum suspensions were obtained from 7-day-old cultures grown on potato dextrose agar at 35°C and adjusted spectrophotometrically to optical densities that ranged from 0.09 to 0.11 at 530 nm. Each inoculum was diluted (1:50) and further diluted (1:20) in each of the two media to obtain two times the density of the larger inoculum (approximately 0.4 × 104 to 5 × 104 CFU/ml) (26) and smaller inoculum (approximately 0.4 × 103 to 5 × 103 CFU/ml) sizes. The actual stock inoculum sizes ranged from 0.9 × 106 to 4.3 × 106 CFU/ml.

(iv) Procedure.

On the day of the test, each microdilution well was inoculated with 100 μl of the diluted (two times) conidial inoculum suspension (final volume in each well was 200 μl) (26). The reference Aspergillus isolates were tested in the same manner as the other isolates; MICs for the QC isolate C. krusei ATCC 6258 were determined by the NCCLS M27-A microdilution method (27). Inoculated trays were incubated at 35°C for 24 to 48 h.

(v) MIC determination.

Two caspofungin MIC end points were determined for each isolate and testing condition: (i) the lowest drug concentration that showed a prominent reduction of growth (approximately ≥50%, or MIC-2) and (ii) a complete growth inhibition (100% inhibition, or MIC-0). Amphotericin B MICs were the lowest drug concentrations that showed complete growth inhibition, and itraconazole MICs were the lowest drug concentrations that showed ≥50% growth inhibition.

(vi) MEC determination.

After 24 h of incubation, caspofungin MECs (Fig. 1 and 2) were also evaluated. For microscopic MECs, a small volume was taken from the first well(s) that showed the presence of round microcolonies and was examined under the microscope. The MEC was the lowest caspofungin concentration in which abnormal, short, and branched hyphal clusters (Fig. 2) were observed compared with the long, unbranched, hyphal elements that were seen in the growth control well. The visual MEC was the first well that showed the presence of round microcolonies (Fig. 1).

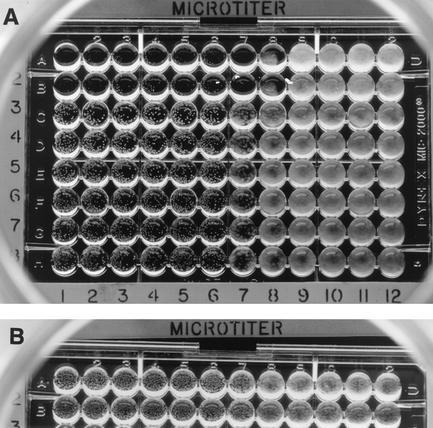

FIG. 1.

(A) Visual or macroscopic caspofungin MECs of 0.12 to 0.25 μg/ml with M3 medium. Isolates tested: A. niger (rows 1 and 2 of the microdilution plate), A. flavus, A. terreus, and A. fumigatus (rows 3 to 8). (B) Visual or macroscopic caspofungin MECs of 0.25 μg/ml with standard RPMI. Isolates tested: A. fumigatus and A. flavus.

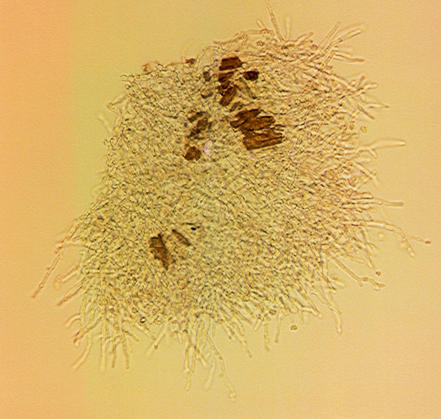

FIG. 2.

Microscopic MEC. Shown is a light micrograph of caspofungin-induced morphological hyphal changes for an isolate of A. fumigatus after 48 h of incubation.

Etest procedure.

Etest was performed by following the manufacturer's instructions (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden) on 150-mm-diameter plates containing solidified RPMI medium with 2% dextrose (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.); plates were inoculated with 400 μl of undiluted stock inoculum suspension. C. krusei ATCC 6258, A. fumigatus ATCC 204305, and A. flavus ATCC 204304 strains were tested each time a set of isolates was evaluated. The plates were incubated at 35°C, and Etest MICs were the lowest drug concentrations at which the border of the elliptical inhibition intercepted the scale on the antifungal strip (Fig. 3) at 24 and 48 h. Small colonies inside inhibition ellipses (trailing growth) were ignored for MIC determination.

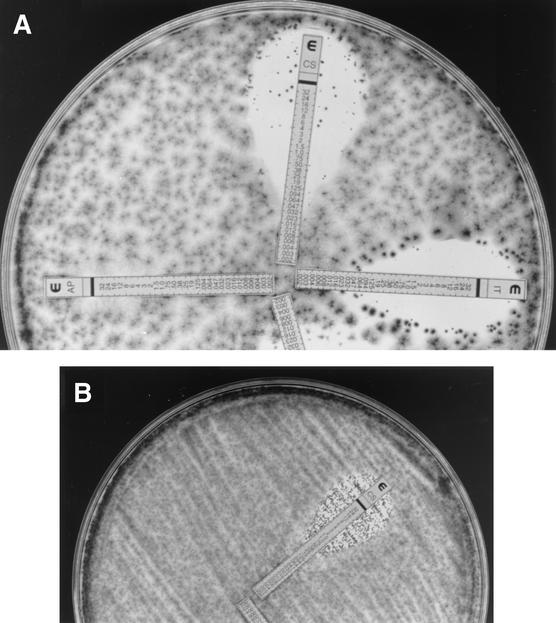

FIG. 3.

(A) Etest MICs of 0.06 (caspofungin and itraconazole) and >8 μg/ml (amphotericin B) for an isolate of A. niger. (B) Caspofungin Etest MIC of 0.5 μg/ml for an isolate of A. fumigatus.

Data analyses.

Both on-scale and off-scale susceptibility values were included in the analyses. Caspofungin MIC and MEC ranges, corresponding geometric means, and MICs and MECs at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited (MIC90s and MEC90s, respectively) were determined for each combination of species, drug, and testing condition evaluated. The same values were obtained for the established agents and for Etest results. MIC and MEC pairs obtained by each combination of testing parameters were compared (e.g., 24- and 48-h MECs versus MICs with each inoculum). Discrepancies between MICs and MECs by the different testing conditions as well as between Etest and broth dilution end points of no more than two dilutions (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, and 2 μg/ml) were used to calculate the percentages of agreement (12-15). Therefore, a total of 200 pairs of susceptibility values were compared to obtain the agreement percentages between each set of testing conditions. E-test MICs were elevated to the next twofold concentration that matched the drug dilution schema of the NCCLS M38-A method (8 to 0.0078 μg/ml) to facilitate comparisons and presentation of results.

RESULTS

Reproducibility for the QC and reference isolates.

Amphotericin B and itraconazole MICs for the QC isolate C. krusei ATCC 6258, A. fumigatus ATCC 204305, and A. flavus ATCC 204304 were within established ranges (4, 26); similar values were obtained by the Etest. Caspofungin MICs and MECs for each Aspergillus control isolate were the same value (or within 2 dilutions) each day tested (on seven different days) by each combination of parameters evaluated; e.g., with the larger inoculum and RPMI medium, MIC and MEC results ranged from 0.12 to 0.2 μg/ml for A. fumigatus ATCC 204305; results decreased 1 to 2 dilutions with the smaller inoculum and M3 medium. Caspofungin MICs for the QC isolate C. krusei were within expected ranges (4).

Effect of the incubation time on caspofungin MICs.

Table 1 summarizes caspofungin MIC-2 (24 and 48 h) and MEC results with RPMI medium and the larger inoculum for the 200 isolates evaluated; comparative itraconazole and amphotericin B MICs also are summarized. Most caspofungin MICs at 48 h were either the same as or increased only 1 to 2 dilutions relative to the 24-h results with the same medium and inoculum size. The exceptions were MIC-2 values (≥3 dilutions higher at 48 h) for 17 of the 200 isolates with both media and inocula. The most relevant increases were from 0.12 to 1.0 μg/ml versus ≥4 μg/ml for 7 of these 17 isolates (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Caspofungin, amphotericin B, and itraconazole in vitro susceptibility data for 200 Aspergillus isolatesa

| Species (no. tested) | Incubation time (h) | Caspofungin

|

Amphotericin B MIC (μg/ml)

|

Itraconazole MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEC (μg/ml)

|

MIC (μg/ml)

|

Range | G (90%) | Range | G (90%) | ||||

| Range | G (90%)b | Range | G (90%) | ||||||

| A. flavus (22) | 24 | 0.12-2 | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.06-2 | 0.31 (0.5) | ||||

| 48 | 0.12->8 | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.2-2 | 1.26 (2) | 0.03-0.2 | 0.11 (0.2) | |||

| A. fumigatus (137) | 24 | 0.12->8 | 0.64 (0.5) | 0.12-4 | 0.31 (0.5) | ||||

| 48 | 0.12->8 | 0.75 (0.5) | 0.2-4 | 1.2 (1.0) | 0.03->8 | 0.71 (0.5) | |||

| A. nidulans (13) | 24 | 0.2-2 | 0.42 (0.5) | 0.2-4 | 0.44 (0.5) | ||||

| 48 | 0.2-4 | 0.51 (0.5) | 0.5-4 | 0.88 (2) | 0.06-0.2 | 1.6 (0.2) | |||

| A. niger (13) | 24 | 0.06-0.5 | 0.16 (0.2) | 0.06-0.5 | 0.14 (0.2) | ||||

| 48 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.5-1.0 | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.12/1.0 | 0.48 (1.0) | |||

| A. terreus (15) | 24 | 0.06-0.5 | 0.12 (0.2) | 0.06-0.2 | 0.12 (0.2) | ||||

| 48 | 0.2-0.5 | 0.27 (0.5) | 0.5-4 | 1.4 (4) | 0.03-0.5 | 0.14 (0.2) | |||

Results obtained with RPMI and an inoculum size of approximately 104 CFU/ml. MIC, ≥50% inhibition for caspofungin and itraconazole.

G, geometric mean; 90%, MIC90 or MEC90.

TABLE 2.

Substantial discrepancies among caspofungin susceptibility data for 10 of 200 Aspergillus isolates under different broth microdilution testing conditionsa

| Speciesb (no. of isolates) | MEC (μg/ml) in:

|

MIC (μg/ml) in medium at:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h

|

48 h

|

|||||

| M3 | RPMI | M3 | RPMI | M3 | RPMI | |

| A. flavus (1) | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06 | >8 |

| A. fumigatus (1) | >8 | >8 | 0.06 | 4 | 0.12 | >8 |

| A. fumigatus (1) | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.06 | >8 |

| A. fumigatus (3) | >8 | >8 | 0.06 | 0.5-1 | 0.06 | >8 |

| A. fumigatus (2) | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 4 |

| A. fumigatus (1) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | >8 |

| A. fumigatus (1) | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 |

Inoculum size, ≈104 CFU/ml; MIC, ≥50% inhibition.

Other species tested: A. nidulans, A. niger, and A. terreus.

Effect of the growth inhibition criterion on caspofungin MICs.

Overall caspofungin MICs-2 were below 1 μg/ml (Table 1), but corresponding MICs-0 were >8 μg/ml (data not shown in Table 1) by all testing conditions evaluated. The exceptions were caspofungin MICs-0 at 24 h for A. niger (MICs-0 were <1 μg/ml for 8 to 13 isolates with M3 and 1 to 11 isolates with RPMI and both inocula) and other isolates with M3.

Effect of medium and inoculum size on caspofungin MECs and MICs.

Growth was insufficient at 24 h for MIC determination with the lower inoculum for 15 isolates (mostly A. terreus with RPMI), but MICs were obtained by the other testing conditions. MIC and MEC results were consistently higher (usually 1 to 2 dilutions) when testing with RPMI than when testing with M3 broth, and these increases were more numerous and dependent on the incubation time with the lower inoculum (31.5% at 24 h and 16.5% at 48 h). Substantial increases caused by RPMI (from a susceptible [≤0.5 μg/ml] rank to less-susceptible and nonsusceptible [4 to >8 μg/ml] ranks) are listed in Table 2. The most relevant MIC increases caused by the larger inoculum at 48 h were for A. flavus (two isolates; for both media, MICs of 0.2 μg/ml versus 2 to >8 μg/ml) and A. fumigatus (MICs for three isolates with RPMI of 0.2 to 0.5 μg/ml versus 4 μg/ml and MICs for 1 isolate with M3 of 0.12 versus 2 μg/ml).

Agreement between visual and microscopic MECs and between MECs and MICs.

It was easier to assess microscopic and visual MECs with M3 (Fig. 1A) than with RPMI (Fig. 1B). The agreement between visual and microscopic MECs was excellent (Fig. 1): 83% of the values were the same, and 17% were within 1 to 2 dilutions. The agreement was greater between visual and microscopic MECs (with RPMI and the larger inoculum) and MICs with RPMI (both inocula) at 24 h (98%) and 48 h (96%) than between MECs and MICs with M3 (80 to 44.4%); substantial discrepancies are listed in Table 2.

Antifungal activity of caspofungin and reference agents.

Caspofungin, amphotericin B, and itraconazole MIC90 ranges were 0.2 to 0.5, 1 to 4, and 0.2 to 1.0 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1). Cross-resistance was not observed among the three agents. For isolates for which high caspofungin end points were obtained, the MICs for the reference agents were low, and isolates for which the amphotericin B MICs were >1 μg/ml and the triazole MICs were 4 to >8 μg/ml had low caspofungin end points. Caspofungin susceptibility values were higher for one A. nidulans isolate (2 to >8 μg/ml) than for the other 12 isolates (0.03 to 0.5 μg/ml). In addition to the high MEC values listed in Table 2, one isolate each of A. fumigatus and A. flavus had slightly higher values (1 to 2 μg/ml) than the other isolates (<0.5 μg/ml).

Agreement between broth dilution MICs and MECs with Etest end points.

Trailing growth also was observed by Etest (Fig. 3) with most isolates and was ignored at both incubation times (same as for MECs and MICs-2). Trailing was less evident for A. niger (Fig. 3A) and more pronounced after 48 h of incubation (especially for A. flavus and A. fumigatus). The agreement between Etest and both broth dilution values was species and testing parameter dependent. The highest overall agreement (93.3%) was between Etest and MEC results with M3 and the larger inoculum, and the lowest agreement was with RPMI and the larger inoculum. When data for A. terreus were excluded, the overall agreement improved (95.4 to 98%) (Table 3). The agreement for A. terreus was 100% between 48-h Etest and microdilution MICs and MECs with the smaller inoculum and RPMI. It is noteworthy that isolates for which high MECs were obtained also had high Etest values at 24 h (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Agreement between caspofungin Etest MICs and broth microdilution MECs and MICs for 169 Aspergillus isolates

| Parametera | Medium | Inoculum size (CFU/ml) | % Agreement for:

|

Overall % agreementb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. fumigatus | A. flavus | A. nidulans | A. niger | A. terreus | ||||

| MEC | RPMI | 104 | 80 | 38 | 60 | 75 | 69.2 | |

| MIC | RPMI | 104 | 85 | 38 | 80 | 75 | 69.2 | |

| MEC | M3 | 104 | 98 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 38.5 | 93.3 (98) |

| MIC | M3 | 104 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 38.5 | 86.1 (98) |

| MEC | RPMI | 103 | 91 | 62 | 60 | 100 | 100 | |

| MIC | RPMI | 103 | 91 | 62 | 80 | 100 | 100 | |

| MEC | M3 | 103 | 95 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 31 | 90.3 (98) |

| MIC | M3 | 103 | 95 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 23 | 90 (95.4) |

MIC, 50% or more growth inhibition at 48 h.

Values within parentheses show percent agreement excluding A. terreus.

TABLE 4.

MECs and Etest results of caspofungin for 169 Aspergillus isolatesa

| Species (no. tested) | Etest MIC (μg/ml)

|

MEC (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 90%b | G meanc | Range | 90% | G mean | |

| A. fumigatus (122) | 0.03->8 | 0.12 | 1.06 | 0.03->8 | 0.2 | 0.63 |

| A. flavus (21) | <0.01-0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03-2 | 0.2 | 0.19 |

| A. nidulans (5) | 0.03->8 | 0.12 | 1.7 | 0.03-8 | 0.2 | 0.21 |

| A. niger (8) | 0.01-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01-0.12 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| A. terreus (13) | 0.06-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.03-0.2 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

Microdilution values with M3 and larger inoculum at 48 h.

90%, MIC90 or MEC90, as indicated, except that for A. nidulans and A. niger, the concentrations are those at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited.

G mean, geometric mean.

DISCUSSION

The M38-A document does not describe testing guidelines for caspofungin or any echinocandins. Caspofungin MICs for molds have been obtained by following a mixture of the NCCLS guidelines for yeasts and molds (26, 27), as well as several growth inhibition criteria (50 to 100%) and incubation times (24 to 72 h) (3, 7, 11, 28). Because of that, this study evaluated M38-A and other broth microdilution parameters as well as the Etest to determine their variability and effect on caspofungin in vitro data for five clinically important Aspergillus spp. This appears to be the first study where all these parameters and methods were examined for caspofungin against a large number of Aspergillus isolates. Caspofungin MICs for Aspergillus spp. are usually below 1 μg/ml (Table 1) (7, 11, 28) if trailing growth is ignored. However, a high geometric mean MIC (27.7 μg/ml) for A. fumigatus has been documented at 48 h (3). Although the 104-CFU/ml inoculum and longer incubation time increased the caspofungin MICs, substantial increases were seen for only a few isolates (Tables 1 and 2); the combined effect of inoculum size and incubation time was also associated with azole MIC increases (17). Abruzzo et al. (2) demonstrated caspofungin efficacy in experimental aspergillosis when the MIC for the infecting isolate was 0.125 μg/ml at 24 h, using the 104-CFU/ml inoculum (26) and the prominent growth inhibition criterion. Therefore, less-stringent parameters (<100% growth inhibition, 24-h incubation, or a combination of these two criteria) could better predict caspofungin in vivo activity. Underestimation of the activity of caspofungin against Candida spp. by using the 100% inhibition criterion has been demonstrated by time-kill curves (10).

In 1994, Kurtz et al. (22) concluded that MECs were superior to MICs in measuring the activity of 1,3,-β-d-glucan synthesis against Aspergillus spp. This finding was corroborated when caspofungin was found equally effective for treating murine coccidioidomycosis, where the MEC was 0.125 μg/ml for each of the two infecting isolates, but corresponding MICs were 8 and 64 μg/ml (18). The agreement between the caspofungin MECs and both 24- and 48-h MICs was good (Table 1). In another study (3), the 48-h incubation had a pronounced effect on caspofungin MICs, and then substantial discrepancies were observed between 24-h MECs and 48-h MICs (0.31 μg/ml versus 4 to 27.7 μg/ml, respectively). The combination of RPMI, the 104-CFU/ml inoculum, and the 24-h incubation yielded a wide MEC range, including both low and high values (Tables 1 and 2). Since caspofungin MECs are more stable than MICs, MECs could be more reproducible end points than MICs, especially for heavy trailers. Agreement between microscopic and visual MECs was excellent; therefore, the convenient visual MEC procedure should be suitable for evaluating caspofungin in vitro antifungal activity against Aspergillus spp. in the clinical laboratory. However, laboratory personnel would require training in the performance of this novel procedure. It is noteworthy that cross-resistance was not observed by any combination of testing conditions since all caspofungin end points were low for resistant isolates (itraconazole-resistant isolates and voriconazole-resistant laboratory mutant strain).

M3 consistently produced lower caspofungin end points than RPMI in this and other studies (3); the reason for the lower caspofungin and amphotericin B MICs obtained with M3 is unknown. Substantial changes in caspofungin susceptibility ranking were minimal between the media for MICs, and there were none for MECs. However, lot variability (24) limits use of M3 and the superiority of its performance over the standard RPMI has been contradicted by results for yeasts versus amphotericin B (6, 24, 27) and for Aspergillus spp. versus the triazoles (15). Therefore, M3 does not offer any advantage over RPMI for the determination of caspofungin MECs.

It has been perceived that agar dilution methods were superior to broth dilution assays in determining the in vitro activities of echinocandins against Aspergillus spp. (5, 22). Recently, the Etest has been evaluated for testing caspofungin against yeasts, and good to excellent (>90%) agreement was documented between NCCLS and Etest procedures using the solidified RPMI with 2% dextrose utilized in this study (32). The agreement between Etest and MEC end points was good to excellent when MECs were obtained with M3 (compared to those obtained with RPMI) for four of the five Aspergillus spp. tested (Table 3), and Etest results matched high MECs at 24 and 48 h. Since trailing growth was heavy at 48 h, especially for A. flavus and some A. fumigatus isolates, the 24-h Etest end points would be easier to evaluate.

In conclusion, based on results from this and other studies, caspofungin MECs could provide a less variable (3) and perhaps more clinically relevant (18) assessment of caspofungin in vitro activity against important Aspergillus spp. The more stable visual and microscopic MECs can be determined by using standard RPMI 1640 broth and an approximately 104-CFU/ml inoculum size at 24 h. Etest may be performed by using solidified RPMI 1640 with 2% dextrose at 24 to 48 h. However, the reproducibility and clinical relevance of broth dilution and agar diffusion end points must be determined in collaborative studies that evaluate selected isolates with different in vitro or in vivo susceptibilities to caspofungin.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks go to Antonio Rezunta for technical support.

This work was partially supported by a grant from Merck.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo, G. K., A. M. Flattery, C. J. Gill, L. Kong,. J. G. Smith, V. B. Pikounis, J. M. Balkovec, A. F. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, H. Rosen, H. Kropp, and K. Bartizal. 1997. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2333-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abruzzo, G. K., C. J. Gill, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, C. Leighton, J. G. Smith, V. B. Pikounis, K. Bartizal, and H. Rosen. 2000. Evaluation of the echinocandin caspofungin against disseminated aspergillosis and candidiasis in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2310-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arikan, S., M. Lozano-Chiu, V. Paetznick, and J. H. Rex. 2001. In vitro susceptibility testing methods for caspofungin against Aspergillus and Fusarium isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:327-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry, A. L., M. A. Pfaller, S. D. Brown, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, C. Knapp, R. P. Rennie, J. H. Rex, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2000. Quality control limits for broth microdilution susceptibility tests of ten antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3457-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartizal, K., C. J. Gill, G. K. Abruzzo, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, P. M. Scott, J. G. Smith, C. E. Leighton, A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and J. Balkovec. 1997. In vitro preclinical studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2326-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy, C., and M. H. Nguyen. 1999. Correlation between in vitro susceptibility determined by E test and response to therapy with amphotericin B: results from a multicenter prospective study of candidemia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1289-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Poeta, M., W. A. Schell, and J. R. Perfect. 1997. In vitro antifungal activity of pneumocandin L-743,872 against a variety of clinically important molds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1835-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denning, D. W., K. Venkateswarlu, K. L. Oakley, M. J. Anderson, N. J. Manning, D. A. Stevens, D. W. Warnock, and S. L. Kelly. 1997. Itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1364-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dismukes, W. E. 2000. Introduction to antifungal drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst, E. J., M. E. Klepser, M. E. Ernst, S. A. Messer, and M. A. Pfaller. 1999. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of MK-0991 determined by time-kill methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33:75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 1998. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2950-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 2001. Comparison of the E-test with the NCCLS M38-P method for antifungal susceptibility testing of common and emerging pathogenic filamentous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1360-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinel-Ingroff, A., M. Pfaller, M. E. Erwin, and R. N. Jones. 1996. Interlaboratory evaluation of Etest method for testing antifungal susceptibilities of pathogenic yeasts to five antifungal agents by using Casitone agar and solidified RPMI 1640 medium with 2% glucose. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:848-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espinel-Ingroff, A., M. Bartlett, R. Bowden, N. X. Chin, C. Cooper, Jr., A. Fothergill, M. R. McGinnis, P. Menezes, S. A. Messer, P. W. Nelson, F. C. Odds, L. Pasarell, J. Peter, M. A. Pfaller, J. H. Rex, M. G. Rinaldi, G. S. Shankland, T. J. Walsh, and I. Weitzman. 1997. Multicenter evaluation of proposed standardized procedure for antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:139-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espinel-Ingroff, A., M. Bartlett, V. Chaturvedi, M. A. Ghannoum, K. Hazen, M. A. Pfaller, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. J. Walsh. 2001. Optimal susceptibility testing conditions for detection of azole resistance in Aspergillus spp.: NCCLS collaborative evaluation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1828-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallis, H. A., R. H. Drew, and W. W. Pickard. 1990. Amphotericin B: 30 years of clinical use. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:308-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gehrt, A., J. Peter, P. A. Pizzo, and T. J. Walsh. 1995. Effect of increasing inoculum sizes of pathogenic filamentous fungi on MICs of antifungal agents by broth microdilution method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1302-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez, G. M., R. Tijerina, L. K. Najvar, R. Bocanegra, M. Luther, M. G. Rinaldi, and J. R. Graybill. 2001. Correlation between antifungal susceptibilities of Coccidioides immitis in vitro and antifungal treatment with caspofungin in a mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1854-1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graybill, J. R., L. K. Najvar, E. M. Montalbo, F. J. Barchiesi, M. F. Luther, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1998. Treatment of histoplasmosis with MK-991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:151-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwen, P. C., M. E. Rupp, and S. H. Hinrichs. 1997. Invasive mold sinusitis: 17 cases in immunocompromised patients and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:1178-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwen, P. C., M. E. Rupp, L. N. Langnas, E. C. Reed, and S. H. Hinrichs. 1998. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: 12-year experience and review of literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1092-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtz, M. B., I. B. Heath, J. Marrinan, S. Dreikorn, J. Onishi, and C. Douglas. 1994. Morphological effects of lipopeptides against Aspergillus fumigatus correlate with activities against (1,3)-β-d-glucan synthase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1480-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lortholary, O., M.-C. Meyohas, B. Dupont, J. Cadranel, D. Salmon-Ceron, D. Peyramond, D. Simonin, and Centre d'Informations et de Soins de l'Immunodeficience Humaine de l'Est Parisien. 1992. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: report of 33 cases. Am. J. Med. 95:177-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozano-Chiu, M., P. W. Nelson, M. Lancaster, M. A. Pfaller, and J. H. Rex. 1997. Lot-to-lot variability of antibiotic medium 3 used for testing susceptibility of Candida isolates to amphotericin B. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:270-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozano-Chiu, M., P. W. Nelson, V. L. Paetznick, and J. H. Rex. 1999. Disk diffusion method for determining susceptibilities of Candida spp. to MK-0991. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1625-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002.. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard M38-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 28.Pfaller, M. A., F. Marco, S. A. Messer, and R. N. Jones. 1998. In vitro activity of two echinocandin derivatives, LY303366 and MK-0991 (L-743,792), against clinical isolates of Aspergillus, Fusarium, Rhizopus, and other filamentous fungi. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, K. Mills, and A. Bolmström. 2000. In vitro susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: comparison of Etest and reference microdilution methods for determining itraconazole MICs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3359-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, A. Houston, K. Mills, A. Bolmstrom, and R. N. Jones. 2000. Evaluation of Etest method for determining voriconazole susceptibilities of 312 clinical isolates of Candida species by using three different agar media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3715-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, A. Houston, K. Mills, A. Bolmstrom, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Evaluation of Etest method for determining posaconazole susceptibilities of 312 clinical isolates of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3952-3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, A. Houston, K. Mills, A. Bolmstrom, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Evaluation of Etest method for determining caspofungin susceptibilities of 726 clinical isolates of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4387-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribaud, P., C. Chastang, J.-P. Latge, L. Baffroy-Lafitte, N. Parquet, A. Devergie, H. Esperou, F. Selimi, V. Rocha, F. Derouin, G. Socie, and E. Gluckman. 1998. Survival and prognostic factors of invasive aspergillosis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:322-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton, A. A., S. E. Sanche, S. G. Revankar, A. W. Fothergill, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1999. In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2343-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szekely, A., E. M. Johnson, and D. W. Warnock. 1999. Comparison of E-test and broth microdilution methods for antifungal drug susceptibility testing of molds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1480-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verweij, P. E., M. F. Q. van den Bergh, P. M. Rath, B. E. dePauw, A. Voss, and J. F. G. M. Meis. 1999. Invasive aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus ustus: case report and review. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1606-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]