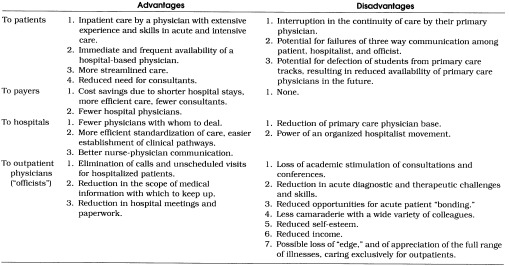

In the last few years, increasing attention has been paid to the concept of the hospitalist, a physician whose practice is limited to hospitalized patients.1, 2 Some of the advantages and disadvantages of the hospitalist system, for patients, providers, hospitals, and purely outpatient physicians (“officists,” to keep the rather awkward terminology consistent), are listed in Table 1. As an internist who, for the last 30 years, has prided himself on his ability to manage patients chronically in any setting, I am particularly concerned about the lower right-hand corner of Table 1—the potential disadvantages of the hospitalist system to an officist. These include such obvious problems as reduced academic stimulation, technical skills, and income, and such intangibles as loss of patient “bonding,” professional “edge,” collegiality, and self-esteem. Trained in a hospital, identified in many patients’ minds with a particular hospital, fortified by the conviction that I can manage the majority of acute medical problems in the hospital, would I revert to the status of that nebulous “LMD” of my housestaff days if removed from one? Would I still be an internist?

Table 1.

Theoretical Advantages and Disadvantages of the Hospitalist System

In trying to answer this latter question, I felt compelled to review what internal medicine actually is. On its Website, the American Board of Internal Medicine states it is,

a scientific discipline encompassing the study, diagnosis, and treatment of non-surgical diseases in adolescent and adult patients. Intrinsic to the discipline are the tenets of professionalism and humanistic values. Mastery of internal medicine requires a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and natural history of disease processes and the acquisition of clinical skills in medical interviewing, physical examination, and procedural competency (www.abim.org).

No mention here of hospitals.

In a 1994 position paper, the American College of Physicians (ACP) offers a definition, not of internal medicine, but of the general internist who practices it. To summarize, he or she is a primary care physician, a physician who evaluates and manages all aspects of illness, an expert in disease prevention, the patient’s “guide and advocate in a complex health care environment,”“an expert in managing patients with advanced illness and diseases of several organ systems” (“equally effective in the office and in the hospital”), a consultant “when patients have difficult, undifferentiated problems,” a resource manager who is “familiar with the science of clinical epidemiology and decision making,” a clinical information manager, and “a generalist in outlook who also possesses special skills that respond to the needs of a particular care environment.”3 In these rapidly changing times, it is difficult for definitions to keep pace with the reality they attempt to define, and so, in spite of inclusion of hospital work in the ACP’s definition, I find that the primary emphasis here, too, is on the intellectual rigor, rather than the environment, of the discipline. As long as that emphasis is preserved, the respect and self-respect that I and other internists have derived from our clinical and technical skills in the hospital could be derived as well, or nearly as well, from purely extramural work. But the simple replacement of forfeited hospital hours with extended office hours is not an appealing strategy, as variety and intellectual challenge would inevitably be lost, and the days behind the desk could become monotonous and long indeed. Rather, I suggest devoting this newly available time to one or more of the following activities:

Expand the care of challenging outpatients—those with rheumatologic, pulmonary, cardiac, endocrine, and infectious diseases—who, over the years, generalists may have turned over to subspecialists as “too complicated.” With the availability of sophisticated outpatient tests and therapies, the officist could continue to take care of “patients with advanced illness and diseases of several organ systems,” cases nearly as acute, and intellectually and emotionally satisfying, as those traditionally associated with hospital work. In following this recommendation, one must honestly consider one’s limits,4 and remain current with emerging data that provide evidence about the quality of the care primary care physicians can render in cases of complex illness.5 In the case of management of patients with advanced HIV infection 6 or acute diverticulitis,7 for example, there is evidence that, by some measures, specialists do a better job than generalists; however, the Medical Outcomes Study shows that, for patients with hypertension and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, at least, “no meaningful differences were found in the mean health outcomes,” whether generalists or specialists rendered the care.8 Indeed, overall, as Donohoe has observed, “the differences [between generalists and specialists]… are not as striking or important to the health of the public at large as those deficiencies in disease management, preventive care, and health maintenance that are common to all physicians.”9 This is obviously fertile ground for further research (see suggestion 5 below).

Replace the collegiality and stimulation of hospital contacts with the office-based collegiality of “case-of-the-week” presentations, communal Medical Knowledge Self Assessment Program reviews, and journal clubs, either face-to-face in larger communities, or electronically (via teleconference, Internet, or intranet 10 discussion groups). Through such interactions, “comprehensive knowledge and understanding” is more likely to be maintained.

Become local experts in medical informatics and evidence-based medicine, through computer links to the National Library of Medicine, the Cochrane Library, drug formularies, decision analysis programs, and the latest patient education materials. This expertise could help maintain the officist role, not only as “clinical information manager,” but also as “consultant when patients have difficult, undifferentiated problems,” and as “the patient’s guide and advocate in a complex health care environment.”

Maximize teaching opportunities when possible in the office, the home, and the nursing home to replace the teaching that occurs in inpatient settings.11 Figures for the number of internists currently teaching residents in the ambulatory care setting are hard to come by, but in the current pool there are 73,000 board-certified internists.12 If they generated approximately 60,000 officists (one hospitalist caring for, say, 25 hospital patients, replacing 5 officists caring for five hospital patients each,13 so that, at the most, five sixths of internists become officists), and they provided one-on-one teaching for the 21,000 current internal medicine residents,14 then about one in three officists could be utilized for housestaff teaching. (The current recommendation, which is one faculty member for no more than three first-year and six second- or third-year residents,15 requires only about 4,600 internists.) As for medical student teaching, according to a recent study, only 19.5% of general internists are involved (or approximately 14,000 teachers for the 67,000 students currently enrolled in U.S. medical schools)16 as opposed to 29.5% of family physicians, and 31.8% of pediatricians.17 Educational credentialing and evaluation,18 and remuneration for ambulatory teaching are two major roadblocks to its promotion (in this same study of medical student teaching, only 9% of teachers were reimbursed for their time). But with increasing emphasis on ambulatory teaching, and the inevitable delegation of some inpatient teaching to hospitalists, medical schools may find the flexibility to support more office-based teaching of students, and teaching hospitals may likewise be able to shift more of their resident-teaching budget to the primary care bases in their communities.19 There is obviously a great need for improvement in an educational system “characterized by variability, unpredictability, immediacy, and lack of continuity,”20 but there is also great potential for professional rewards for those able to make the commitment.

Pursue clinical outpatient research projects, again either with other local officists, or via electronic communities. Currently only 6% of young, non-university-affiliated general internists participate in research.21 The reasons for this are many and obvious, including funding difficulties, time constraints, and lack of role models and practical support.22–24 But advice and support are increasingly available, including practice-based research networks (the majority of which consist, interestingly, not of internists, but of family physicians) and initiatives by some managed care organizations and academic medical centers.25, 26 The collegiality arising out of joint projects, and out of preparation and discussion of any resulting papers, would go a long way toward replacing the conventional collegiality of hospital interactions.

As hospital Department of Medicine meetings and grand rounds become less relevant to an entirely office-based practice, communicate more with fellow officists through professional associations like the ACP–American Society of Internal Medicine and the Society of General Internal Medicine. Though of the total U.S. internist population of 122,000,27 some 80,000 (66%) are members of the ACP, only 2,500 (2%) are members of the Society of General Internal Medicine.28 For there is always the danger that, as their hospital affiliations wither away, office-based physicians will seek shelter in the only structures left standing on their medical landscape, their business and managed care organizations. Important though these institutions are from a practical point of view, their prime function is not the furthering of the internist’s calling.

Though the above activities would ideally be pursued by all internists regardless of setting, they have hitherto been pursued only by the more enlightened and organized among us and they could produce for all of us professional benefits approaching or equivalent to those of inpatient practice. Many, however, are not remunerative in and of themselves. In order to replace lost hospital income, one would have to divide the time saved from hospital responsibilities—for the average internist in 1996, an average of 11.5 hours per week on rounds,29 plus time spent on inpatient student and housestaff teaching, and hospital committee work—between these activities and more lucrative ones. The latter, of course, often involve procedures (stress tests and sigmoidoscopies, for example), an aspect of internal medicine included in the Board’s definition above. (This suggestion should not be construed as encouragement to perform unnecessary procedures, but rather to develop skills that would reduce the need to refer patients—and, in a managed care world, the cost to the primary care physician of such referrals—for indicated procedures.) Whether this maneuver would generate adequate income to “fund” the following activities is debatable; though in a capitation system, seeing more patients does not necessarily mean generating more income either. For some of the activities, other funding sources such as teaching stipends (suggestion 4) or research grants (suggestion 5) would need to be identified.

In summary, as noted in Table 1, although the hospitalist movement has much to recommend it, it also has the potential to jeopardize the identity of internists marooned in their offices as a result. Perhaps the movement will never take hold, but if it does, officists, rather than sitting back, passive and disenfranchised, should mount a movement of their own, taking advantage of the professional opportunities of the times. Harking back to definitions of internal medicine, they should capitalize on what they have always done well, and what attracted them to internal medicine in the first place. That that attraction was often associated with hospitals was, after all, only a matter of 20th-century circumstance.

References

- 1.Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gesensway D. Are hospitalists a threat to the identity of internists? ACP Observer. February 2, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sox HC, Scott HD, Ginsburg JA. The role of the future general internist defined. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:616–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-8-199410150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gianakos D. Accepting limits. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1059–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franks P, Nutting PA, Clancy CM. Health care reform, primary care, and the need for research. JAMA. 1993;270:1449–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner BJ, McKee L, Fanning T, Markson LE. AIDS specialist versus generalist ambulatory care for advanced HIV infection and impact on hospital use. Med Care. 1994;32:902–16. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarling EJ, Piontek F, Klemka-Walden L, Inczauskis D. The effect of gastroenterology training on the efficiency and cost of care provided to patients with diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1859–62. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenfield S, Rogers W, Mangotich M, Carney MF, Tarlov AR. Outcomes of patients with hypertension and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus treated by different systems and specialties—results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1436–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donohoe MT. Comparing generalist and specialty care—discrepancies, deficiencies, and excesses. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1596–608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelingher J. It’s time for intranets. MD Comput. 1997;14:274–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsch SL, Noble J. Community-Based Teaching: A Guide to Developing Education Programs for Medical Students and Residents in the Practitioner’s Office. Philadelphia, Penn: American College of Physicians; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randolph L, editor. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US 1997-1998. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez ML, editor. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Medical Practice 1997. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graduate Medical Education Directory 1997–1998. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 1231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graduate Medical Education Directory 1997–1998. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medical School Admission Requirements—United States and Canada 1998–1999. 48th ed. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1997. p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinson DC, Paden C, Devera-Sales A, Marshall B, Waters EC. Teaching medical students in community-based practices: a national survey of generalist physicians. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:487–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassirer JP. Redesigning graduate medical education—location and content. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:507–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boex JR, Blacklow R, Boll A, et al. Understanding the costs of ambulatory care training. Acad Med. 1998;73:943–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irby DM. Teaching and learning in ambulatory care settings: a thematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:905. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199510000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mainous AG, Hueston WJ. Characteristics of community-based primary care physicians participating in research. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stange KC. Primary care research: barriers and opportunities. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:192–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueston WJ, Mainous AG. Family medicine research in the community setting: what can we learn from successful researchers? J Fam Pract. 1996;43:171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K. Conducting research as a busy clinician-teacher or trainee—starting blocks, hurdles, and finish lines. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:360–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02600048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutting PA. Practice-based research networks: building the infrastructure of primary care research. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bass MJ, Dunn EV, Norton PG, Stewart M, Tudiver F, editors. Conducting Research in the Practice Setting. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randolph L, editor. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US 1997–1998. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travers B, editor. Encyclopedia of Medical Organizations and Agencies. 7th ed. Detroit, Mich: Gale Research; 1997. pp. 113–145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez ML. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Medical Practice 1997. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1997. p. 64. [Google Scholar]