Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Most older people with psychiatric disorders are never treated by mental health specialists, although they visit their primary care physicians regularly. There are no published studies describing the broad array of psychiatric disorders in such patients using validated diagnostic instruments. We therefore characterized Axis I psychiatric diagnoses among older patients seen in primary care.

DESIGN

Survey of psychopathology using standardized diagnostic methods.

SETTING

The private practices of three board-certified general internists, and a free-standing family medicine clinic.

PARTICIPANTS

All patients aged 60 years or older who gave informed consent were eligible.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

For the 224 subjects completing the study, psychiatric diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Point prevalence estimates used weighted averages based on the stratified sampling method. For the combined sites, 31.7% of the patients had at least one active psychiatric diagnosis. Prevalent current disorders included major depression (6.5%), minor depression (5.2%), dementia (5.0%), alcohol abuse or dependence (2.3%), and psychotic disorders (2.0%). Dysthymic disorder and primary anxiety and somatoform disorders were less common and frequently comorbid with major depression.

CONCLUSIONS

Mental disorders, particularly depression, are common among older persons seen in these primary care settings. Clinicians should be particularly vigilant about depression when evaluating older patients with anxiety or putative somatoform symptoms, given the relatively low prevalences of primary anxiety and somatoform disorders.

Keywords: psychopathology, depression, elderly, primary care

The psychopathology of older persons in primary care settings warrants empirical attention for several reasons. There are well-documented demographic imperatives, including the changing age distribution of the population and the disproportionate rise in health care expenditures with age.1 Older people with psychiatric disorders are even less likely to be seen in mental health settings than younger patients, yet they are more likely to see their primary care physician regularly.2–4 Older patients who complete suicide often have seen their primary care provider shortly before their death.5 Data from other settings suggest that the epidemiology of mental disorders changes across age groups. In community samples, long term care settings, and medical inpatient units, mood, cognitive disorders (e.g., dementias), and secondary disorders (i.e., “organic”) appear to predominate in later life,6–8 as contrasted with the high prevalences of substance use, anxiety, and personality disorders among younger persons. Accordingly, there has been increasing recognition of the need for greater attention in primary care to mental disorders in the elderly,9,10 an imperative made stronger by the greater general health care costs associated with depressive symptoms in these patients.11

To date, such calls have been met with surprisingly little empirical research. Most primary care studies of mental disorders have used mixed age samples with a mean age under 45 years,12,13 or have specifically excluded persons over age 60 or 65 years.14 Among those that did focus on older persons, almost all limited their field of view to depression.15–20 Of these, only one investigative group used a well-validated structured interview to assign depression diagnoses.15 Most relied on self-report depression scales that assess symptoms but cannot assess the presence or absence of specific diagnoses, and therefore cannot directly measure diagnostic prevalences. Determination of the presence or absence of psychiatric disorders requires examiner judgment in applying diagnostic criteria to clinical data. To our knowledge, no published report has studied systematically the broader array of mental disorders in older primary care patients using a validated diagnostic instrument. Given this context, we planned to describe the prevalences of Axis I psychiatric diagnoses in a group of older patients attending primary care practices, using a well-validated semistructured diagnostic interview. We also sought to explore differences in prevalences between genders, because in younger populations and in community-based elderly, mood, anxiety, and dementing disorders are more common among women, while alcohol abuse and dependence are more common among men.

METHODS

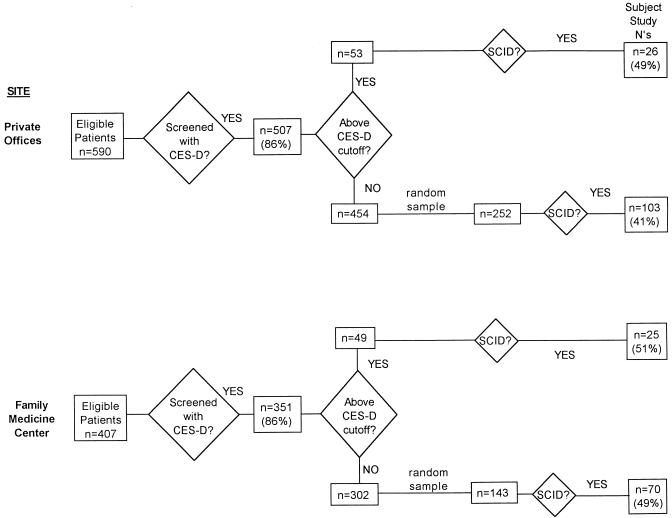

Subjects were recruited from private internal medicine offices or from a family medicine clinic. Stratified sampling techniques were used to oversample patients with depressive symptoms21; this was done to facilitate other studies focusing on patients with depressive conditions. The recruitment process, described in detail in this section, is shown in the flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study recruitment process.

The 129 subjects from the private offices were included in a previously published study.22 The private offices were those of three board-certified general internists, clinical faculty at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry who maintained full-time private practices. Their offices drew on a patient population that came predominantly from middle-class neighborhoods in the city of Rochester, and from the mostly middle-class and upper-middle-class adjacent suburbs. Two of the practices shared office space, and the third had an adjacent office; all three shared on-call responsibilities for the combined practices. Each of the two office groupings was joined by a physician assistant part way through the subject recruitment period.

Patients were screened 2 or 3 1/2 days per week with a self-report depression symptom scale, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D),23 to allow oversampling of patients with depressive symptoms and syndromes. All patients aged 60 years and over who appeared for visits in these offices during these times were eligible for screening, with the rare exception of patients unable to complete the questionnaires owing to gross impairments in communication skills or language barriers (n = 9). With informed consent (procedures approved by the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Research Subjects Review Board), patients completed the CES-D in the office. Screening was performed at first by office staff (March–May 1994), during which time 83 (79%) of 105 patients eligible for screening completed the CES-D. During the majority of the enrollment period (May 1994 – June 1995), screening was performed by research personnel, and 424 (87%) of 485 eligible patients completed the CES-D. The lower screening completion rate by office staff as compared with research staff was due to potentially eligible patients being missed, rather than a higher patient refusal rate.

Screening was conducted in similar fashion by research personnel two half-days per week from July 1995 to June 1996 at the University of Rochester Family Medicine Center at Highland Hospital. This free-standing clinic, located near Highland Hospital, is the home of the University’s Family Medicine Department and residency program, and serves a predominantly urban and poorer population than the private offices. Clinicians include faculty attending physicians in family medicine, family medicine residents, and family medicine nurse practitioners. During the enrollment period, 436 patients aged 60 years or older visited the Family Medicine Center. Twenty-nine of these were ineligible for screening, either because of gross communication impairments (14 were mentally retarded—the Family Medicine Center serves several group homes for mentally retarded residents; 1 had advanced Alzheimer’s disease) or because of a language barrier without available family or other translator (n = 14). Of the remaining 407 eligible subjects, 3 were missed, 53 refused screening, and a total of 351 (86%) completed the CES-D.

Selected screened patients were approached by telephone for informed consent to complete an in-depth interview including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID),24 within 4 weeks of their primary care visit. To enrich the study group with persons with significant depressive symptoms and syndromes, the sample was stratified on the CES-D: all patients scoring>21 were approached for SCID interview, and a random sample of those scoring ≤21 were approached, up to a maximum of three SCID interviews per week. The SCID interview was held either in the patient’s home (n = 198), at our research offices at the University of Rochester Medical Center (n = 23), or at another location (n = 3).

At the private offices, 53 patients scored above the CES-D cutoff, and the SCID interview was completed with 26 (49%) of them; the remainder either refused the interview outright or stated they were unable to schedule the interview within the 4-week time frame. Of those scoring below the cutoff, 252 were selected randomly and approached for SCID interview, and 104 (41%) of these did complete this in-depth assessment. To allow group comparisons of medical illness severity, medical charts were reviewed by a physician-investigator (JML) on a random sample of 50 patients (25 above and 25 below the CES-D cutoff) who were approached but did not complete the SCID interview, and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS),25 a validated measure of overall organ system burden, was completed. (The CIRS was completed in similar fashion for all study participants.) Subjects scoring above the cutoff who completed the SCID assessments did not differ statistically from those not completing the SCID on any of the variables available for comparison (age, gender, CES-D score, CIRS, and visit type). Patients below the cutoff who completed the SCID interview did not differ from those completing the SCID on age, CES-D score, or visit type, but did have a greater proportion of men (45% vs 30%, p = .017) and a higher score on the CIRS (mean 6.5 vs 4.6, p = .0003).

At the Family Medicine Center, 49 patients scored above the CES-D cutoff, and the SCID interview was completed with 25 (51%) of them; again, the remainder either refused the interview outright or stated they were unable to schedule the interview within the 4-week time frame. Of those scoring below the cutoff, 143 were selected randomly for SCID interview, and 70 (49%) completed this in-depth assessment. Patients scoring above the cutoff who completed the SCID interview did not differ significantly from those not completing the interview on age, gender, or visit type, but did have a higher score on the CES-D (mean 31.1 vs 27.9, p = .047). Patients below the cutoff who completed the SCID interview did not differ on age, gender, or CES-D score, but did differ significantly on visit type (more likely to be seen for a scheduled follow-up appointment) (Fisher’s Exact Test, p = .007).

The in-depth diagnostic assessment was based on the SCID, a validated and reliable instrument that depends on rater clinical judgment, using all available sources of data including the patient’s report, family report, and medical records, to arrive at Axis I diagnoses. The SCID diagnoses used indicate current disorders, as well as certain fully remitted conditions (major depression and substance use disorders only) and partially remitted major depression (i.e., symptoms improved below the diagnostic threshold for major depression but still present at clinically significant levels). The SCID interview was administered by master’s-level prepared raters trained in the use of the SCID and other study measures by research personnel in the Department of Psychiatry’s Program in Geriatrics and Neuropsychiatry. A physician-investigator (JML) reviewed the primary care record for all subjects, along with all other available outpatient and inpatient medical and psychiatric records, to facilitate completion of study measures.

Study patients were presented by the SCID rater at a weekly consensus conference of program investigators, raters, and other research personnel. Consensus diagnoses were assigned based on the SCID. The SCID does not include a section to assess the diagnosis of dementia; consensus diagnoses of dementia were assigned using DSM-III-R criteria,26 based on patient (and when possible family) responses to specific probe questions about cognitive decline and related functional impairment, score on the Mini-Mental State Examination,27 and all other available clinical and laboratory data. As well, a diagnosis of current minor depressive disorder was assigned based on the SCID data, using the criteria proposed in the appendix to DSM-IV (the diagnostic criteria are identical to those for major depression, except that a minimum of two symptoms rather than five are required, with one symptom necessarily being depressed mood or diminished interest or pleasure).28 For all depressive diagnoses, an inclusive approach was used regarding symptoms. That is, symptoms were counted toward the criteria for depressive diagnoses without attempt to attribute them to “psychiatric” or “medical” causes, as has been recommended by our group and others,29 because of both the need to include the broad range of medical comorbidity in the study of later life depressions, and the arbitrary nature of most decisions regarding attribution. Thus, the diagnosis of secondary or “organic” mood disorder was not used.

Prevalence estimates for specific diagnostic groups were based on weighted combinations of stratum-specific rates because of the stratified sampling strategy, i.e., the weighting reconstructed the proportion of subjects scoring above and below the CES-D cutoff in the parent population for each diagnosis. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for these prevalence estimates were calculated by using a normal approximation; several of the confidence intervals had lower limits that were negative numbers, but these lower limits are reported as 0% because a prevalence rate cannot be less than 0. Standard deviations for the prevalence estimates were obtained by appropriately weighting the variances for individual rates within each CES-D-defined stratum, which were calculated using the variance of the binomial distribution. Comparison of prevalence rates by gender used approximate Z tests. All reported p values are two-sided because of the number of comparisons performed.

RESULTS

The 129 subjects from the private offices had a mean age of 71.1 years (range 60–86 years) and a mean of 13.7 years of education (range 8–17 years.) Of this group, 75 (58%) were female, and 126 (98%) were white. The 95 subjects from the Family Medicine Clinic had a mean age of 70.0 years (range 60–89 years) and a mean of 12.2 years of education (range 1–17 years.) Sixty-four (67%) were female, and 75 (79%) were white.

Prevalence estimates for individual Axis I mental disorders by gender are shown in Table 1. As expected, mood and anxiety disorders were more common among women, while both active and remitted alcohol dependence was more common among men. However, as shown in Table 1, the only statistically significant differences in prevalence rates between genders were as follows: women had a trend toward a higher rate of anxiety disorders and significantly higher rates of active major depression and fully remitted major depression, while men had a higher rate of fully remitted alcohol use disorders.

Table 1.

Prevalence Estimates of Axis I Mental Disorders by Gender

| Prevalence Rate (95% Confidence Interval), % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorders (n) | Men | Women | Combined |

| Active | |||

| Major depression (23)* | 3.6 (1.4, 5.8) | 8.4 (4.5, 12.3) | 6.5 (4.0, 9.1) |

| Major depression, in partial remission (9) | 1.2 (0, 2.7) | 4.5 (1.1, 8.0) | 3.2 (1.0, 5.4) |

| Minor depression (13) | 3.2 (0, 6.9) | 6.6 (2.4, 10.8) | 5.2 (2.3, 8.2) |

| Dysthymic disorder (4) | 0.6 (0, 1.7) | 1.2 (0, 2.4) | 0.9 (0.1, 1.9) |

| Dementia (12) | 5.7 (1.0, 10.3) | 4.6 (0.9, 8.3) | 5.0 (2.1, 7.9) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence (5) | 4.5 (0, 8.9) | 0.8 (0, 2.5) | 2.3 (0.2, 4.3) |

| Psychotic disorder (6)† | 1.9 (0, 4.6) | 2.0 (0, 4.1) | 2.0 (0.3, 3.6) |

| Bipolar disorder (3) | 1.9 (0, 4.6) | 0.4 (0, 1.1) | 1.0 (0, 2.2) |

| Anxiety disorder (4)‡ | 0 | 2.5 (0, 5.0) | 1.5 (0, 3.0) |

| Somatoform disorder (4)§ | 1.3 (0, 3.8) | 1.6 (0, 3.6) | 1.5 (0, 3.0) |

| Benzodiazepine dependence (1) | 0 | 0.4 (0, 1.1) | 0.2 (0, 0.7) |

| Uncomplicated bereavement (1) | 0 | 0.4 (0, 1.1) | 0.2 (0, 0.7) |

| Other (2)∥ | 1.3 (0, 3.8) | 0.8 (0, 2.5) | 1.0 (0, 2.4) |

| Fully remitted | |||

| Major depression, in full remission (17)¶ | 3.9 (0, 8.2) | 11.3 (5.7, 16.9) | 8.4 (4.5, 12.2) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence, in full remission (20)# | 15.4 (7.5, 23.3) | 5.0 (1.2, 8.7) | 9.1 (5.2, 13.0) |

| Other substance use disorder, in full remission (2)** | 0 | 1.2 (0, 3.0) | 0.7 (0, 1.8) |

Significant difference in prevalence rate by gender, p = .036.

Psychotic disorder includes schizophrenia (n = 3), schizoaffective disorder (n = 2), and delusional disorder (n = 1).

Anxiety disorder includes panic disorder with agoraphobia (n = 1), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 1), and simple phobia (n = 2); significant difference in prevalence rate by gender p = .057.

Somatoform disorder includes somatoform pain disorder (n = 3) and body dysmorphic disorder (n = 1).

Other includes organic personality disorder (n = 1) and organic delusional disorder (n = 1).

Significant difference in prevalence rate by gender p = .039.

Significant difference in prevalence rate by gender p = .019.

Other substance use disorder includes amphetamine dependence (in full remission) (n = 1) and neuroleptic abuse (in full remission) (n = 1).

There was some diagnostic comorbidity, as shown by the following prevalence rate estimates (± SD): 62.3% (± 3.2%) had no Axis I diagnoses, 28.3% (± 3.0%) had one, 7.7% (± 1.7%) had two, 1.5% (± 0.7%) had three, and 0.2% (± 0.2%) had four Axis I diagnoses. Excluding patients whose diagnoses were solely fully remitted conditions (e.g., major depression in full remission, or alcohol or other substance dependence in full remission), the estimated prevalence for persons having at least one active psychiatric diagnosis was 31.7% (± 1.4%).

Given the high prevalence of mood disorders, we examined the psychiatric comorbidity among patients with major and minor depression. Twelve (52%) of 23 patients with active major depression had at least one other diagnosis, as did 3 (33%) of 9 with major depression in partial remission, 4 (24%) of 17 with major depression in full remission, and 2 (15%) of 13 with active minor depression. Most patients in our sample with dysthymic disorder (3 of 4), anxiety disorders (2 of 4), somatoform disorders (3 of 4), and dementia (6 of 12) also had diagnoses of major or minor depression. The estimated prevalences (± SD) for these conditions without concurrent major or minor depression were as follows: dysthymia 0.2% (± 0.2%), anxiety disorders 0.7% (± 0.6%), somatoform disorders 0.5% (± 0.5%), and dementia 3.1% (± 1.2%).

DISCUSSION

The most prominent finding from our data is that mental disorders are common in older primary care patients: 31.7% of patients had at least one active psychiatric condition at the time of interview; 18.2% had fully remitted psychiatric conditions (major depression or alcohol or substance use disorders) that require clinical vigilance and possibly maintenance therapies. Gender differences generally were in accord with previous findings in community elderly and younger primary care populations, although statistically significant differences between men and women were few in our relatively modest sample size.

These data also support the emphasis in previous literature on depressive disorders in older primary care patients, given their high combined prevalence (11.7% for fully syndromic major or minor depression, plus an additional 11.6% for partially or fully remitted major depression) and the fact that many of the other mental disorders had substantial comorbidity with major depression. In fact, the prevalence of major depression was comparable to that found in most primary care studies of younger or mixed-age subjects,30–32 and greater than community-based prevalence estimates for major depression in older persons.9 In contrast to younger populations, dysthymic disorder was relatively uncommon; when present it was most often part of so-called double depression (i.e., a superimposed major depression was comorbid).

In addition to depression, dementia, alcohol abuse and dependence, and chronic psychotic disorders were common enough to warrant further clinical and investigative attention. The relatively low prevalences of anxiety and somatoform disorders contrast sharply with findings in younger populations. Their relative rarity without a concomitant depressive disorder diagnosis gave empirical support to the clinical adage often espoused by geriatric mental health specialists: when an older patient presents with anxiety or “hypochondriasis,” a primary anxiety or somatoform disorder should be lower on the list of differential diagnostic possibilities, while a high degree of suspicion for the presence of contributing physical illnesses, mood, or cognitive deficit disorders must be maintained.

Several limitations of our study must be acknowledged to provide a context for interpreting our findings. The first is the issue of sample bias. Most, but not all, potentially eligible patients were screened. A substantial percentage of screened patients who were approached for the SCID interview did not complete this interview and so were not included in the study. However, our success rate in completing SCID interviews was comparable to the only published primary care investigation to use the full-length SCID, which studied patients of mixed age.32 Moreover, among the variables available for comparison of study subjects with subjects not completing the SCID, differences between the groups were few. It is likely that our results underestimated the prevalence of dementing disorders, both because severe cognitive deficits precluded participation in our protocol, and because very mild dementias may have been missed using our methods; indeed, our estimates of the prevalence of demen-tias were lower than those of surveys of community-based elderly.

Our findings may not apply to patients in other settings. Replication studies are warranted among populations with greater percentages of persons who are not white, or among inner-city or rural settings. Larger studies also should examine prevalence variability for specific psychiatric disorders among different practice sites and geographic regions, as well as among age subgroups.

In summary, mental disorders are common among older persons attending primary care settings. Clinicians must be particularly vigilant about depressive conditions, given their prevalence, medical and psychiatric comorbidity, the availability of simple and effective office screening measures (as contrasted with dementia),22,33 and the clearly demonstrated benefits of psychological and pharmacological treatments for major depression.9 Physicians also must remain mindful of the high prevalence of minor depression, while recognizing that thus far there has been no empirical investigation regarding response to specific treatment strategies. In addition to instituting clinical trials, researchers must continue to respond to the larger public health imperative by focusing investigative efforts on the neurobiological, psychological, and psychosocial concomitants of depression in primary care elderly, to guide our evolving models of pathogenesis and ultimately lead to more specifically targeted therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients and staff in the practices of Drs. Judith Allen, Russell Maggio, and Bruce Peyser, and at the University of Rochester Family Medicine Center at Highland Hospital. They also thank Cynthia Doane, MSPH, and Tamson Kelly Noel, MS, for study coordination; Carrie Irvine, BS, Holly Stiner, Aaron Gleason, and Gerard Kiernan, MD, for technical assistance; and Drs. Yeates Conwell, William Hall, and T. Franklin Williams for reviewing earlier drafts of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants K07 MH01113 (Dr. Lyness) and T32 MH18911 (Dr. Caine).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mittelmark MB. The epidemiology of aging. In: Hazzard WR, Bierman EL, Blass JP, Ettinger Wh Jr, Halter JB, editors. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1994. pp. 135–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd M, Wilkinson G. Primary care as the middle ground for psychiatric epidemiology. Psychol Med. 1988;18:263–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700007807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkisson CC, Zich JM, editors. Depression in Primary Care: Screening and Detection. New York, NY: Routledge; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conwell Y. Suicide in elderly patients. In: Schneider LS, Reynolds Cf III, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ, editors. Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig HG, Blazer DG. Epidemiology of geriatric affective disorders. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8:235–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tariot PN, Podgorski CA, Blazina L, Leibovici A. Mental disorders in the nursing home: another perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1063–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.7.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker FM, Lebowitz BD, Katz IR, Pincus HA. Geriatric psychopathology: an American perspective on a selected agenda for research. Int Psychogeriatr. 1992;4:141–56. doi: 10.1017/s1041610292000966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Depression in Late Life. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA. 1992;268:1018–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caine ED, Lyness JM, King DA. Reconsidering depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;1:4–20. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199300110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older: a 4-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997;277:1618–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440052032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1995;274:1511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Simon GE. Occurrence, recognition, and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:636–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Costa e Silva JA, et al. An international study of psychological problems in primary care: preliminary report from the World Health Organization collaborative project on ‘psychological problems in general health care.’. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:819–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820220075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans S, Katona C. Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in elderly primary care attenders. Dementia. 1993;4:327–33. doi: 10.1159/000107341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson GM, Schulz R. Physical illness and symptoms of depression among elderly outpatients. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:343–51. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borson S, Barnes RA, Kukull WA, et al. Symptomatic depression in elderly medical outpatients, I: prevalence, demography, and health service utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:341–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Depression in late life: the use of clinical characteristics to focus screening efforts. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M9–M14. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.m9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kukull WA, Koepsell TD, Inui TS, et al. Depression and physical illness among elderly general medical clinic patients. J Affect Disord. 1986;10:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oxman TE, Barrett JE, Barrett J, Gerber P. Symptomatology of late-life minor depression among primary care patients. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:174–80. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(90)72191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson SK. Sampling. New York, NY: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in primary care elderly: a comparison of the CES-D and the GDS. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:449–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1992;7:343–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed., revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:185–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyness JM, Bruce ML, Koenig HG, et al. Depression and medical illness in late life: report of a symposium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams Jw, Jr, Kerber CA, Mulrow CD, Medina A, Aguilar C. Depressive disorders in primary care: prevalence, functional disability, and identification. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02599568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL. Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:267–76. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]