Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the predictive validity and calibration of the pneumonia severity-of-illness index (PSI) in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

PATIENTS

Randomly selected patients (n=1,024) admitted with CAP to 22 community hospitals.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Medical records were abstracted to obtain prognostic information used in the PSI. The discriminatory ability of the PSI to identify patients who died and the calibration of the PSI across deciles of risk were determined. The PSI discriminates well between patients with high risk of death and those with a lower risk. In contrast, calibration of the PSI was poor, and the PSI predicted about 2.4 times more deaths than actually occurred in our population of patients with CAP.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that the PSI had good discriminatory ability. The original PSI overestimated absolute risk of death in our population. We describe a simple approach to recalibration, which corrected the overestimation in our population. Recalibration may be needed when transporting this prediction rule across populations.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, epidemiology, mortality, case-mix adjustment, logistic regression

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is associated with high and variable mortality rates among hospitalized patients.1,2 The ability to assess prognosis of people with CAP is important for several reasons.3 Accurate assessment of prognosis may help physicians make clinical decisions about hospitalization and management. Further, a prognostic index can be used to adjust for case mix when comparing outcomes of care across populations of patients. Finally, assessment of prognosis may be useful in a research setting to adjust comparisons in observational studies for case mix or to help ensure that assignment of patients to different treatments in a randomized study is balanced with respect to severity.

A variety of generic prognostic indicators or severity scores are available.4–9 Although these scores can be useful, it has been suggested that disease-specific case-mix adjustment systems may provide more accurate information.8 Fine and his colleagues have described a disease-specific clinical prediction rule for CAP called the pneumonia severity-of-illness index (PSI).8,10 Clinicians and investigators should evaluate prognostic scores like the PSI before using them.11–13 Evaluation measures that can easily be used include the prediction rule’s ability to distinguish patients who die from those who live (discriminatory ability) and the correspondence between the predicted and observed mortality in groups of patients (calibration).11 The purpose of this article is to validate the PSI in a new patient population and to describe a modification of the PSI that improved the index’s calibration.13

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective chart review of randomly selected patients admitted with CAP to 22 community hospitals participating in a quality improvement project.

Study Population

Patients admitted between July 1, 1994, and June 30, 1995, who were aged 20 years and older and who had a International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification(ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code of 480.0–480.9, 481, 482.0, 482.1, 482.2, 482.30–482.39, 482.4, 482.81–482.83, 482.89, 482.9, 483.0, 483.8, 485, 486, or 487.0 for the principal cause for hospitalization were eligible for inclusion in the study if pneumonia was mentioned as a primary diagnosis in the medical record during the first 12 hours of hospitalization and listed as the primary cause of admission at discharge.

Patients were excluded if they were transferred from another acute care facility; were hospitalized within the previous 14 days; died within 4 hours of admission; were HIV positive; or had received a transplant, radiation, or cytotoxic therapy during the 30 days prior to admission.

Patient Sample

Fifty records from eligible patients at each hospital were randomly selected from the study cohort in each hospital.

Data Abstraction

Each hospital copied the sample patient records (charts) for central abstraction by trained nurse abstractors who used a standardized, piloted abstraction tool to collect all patient-specific information. Interrater reliability was determined with a random reabstraction of 5% of the charts.

Computation of Patient Pneumonia Severity Index

We calculated the PSI for each patient on the basis of the patient’s unique set of prognostic indicators and the gender- and age-specific logistic regression parameters as described by Fine at al.8 We treated missing information by imputing the value for the reference category (normal or lowest risk) in the calculation.

Data Analysis

We estimated the discriminatory ability of calculating the c statistic, an estimate of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.14 The c statistic measures the ability of the model to discriminate between those who will and those who will not die and is bounded by the values of 0.5 and 1.14 If the predicted probabilities of those who die are uniformly greater than those who survive, then the value of the c statistic is 1; if they are randomly distributed among the two groups, the value of the c statistic should be about 0.5.14,15

We assessed the calibration of the original and recalibrated PSI by dividing the patients into deciles of predicted risk of dying.11,16 We divided the PSI scores into deciles and used a Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2goodness-of-fit test to assess the predictive properties of the index over a range of estimated risks of death.11 We restricted our evaluation to include risk strata for which the expected number of deaths was at least 5. Results were similar when we combined the lower deciles into a single stratum with at least 5 deaths or when we based the test on a smaller number of equal-sized groups defined by tertiles of risk.

Because the observed mortality was considerably different from that predicted by the PSI for our 22 study hospitals, we recalibrated the PSI. For each patient, we transformed the patient-specific PSI score using the logit transformation.16 We entered the transformed score into a logistic model as an independent variable. This procedure yielded a recalibrated model with a new (maximum likelihood estimate) intercept. This approach to recalibration leads to a model with the property that the sum of the predicted deaths equals the sum of the observed deaths, a feature of maximum likelihood estimators in logistic regression.16 Then we recalculated the probability of death for each patient by appropriate inversion of the logistic transformation. We estimated the discriminatory ability and calibration of the transformed score as described above. Finally, we compared calibration and predictive ability of the PSI across five groups of patients defined by the same percentiles of the PSI as were used by Fine et al.8

Finally, we evaluated possible improvements in the score by adding more predictors to the logistic regression model that already included the logit-transformed PSI. We calculated confidence intervals and p values using both an approach based on generalized estimating equations that accounted for possible correlation or clustering of outcomes within a hospital and one based on ordinary logistic regression.17 The results using the generalized estimating equations were similar to those from ordinary logistic regression, so we have reported only the latter.

RESULTS

Our sample included 1,024 patients with CAP from 22 hospitals, an average of 47 patients per hospital. The mean age was 67 years, with a range from 20 to 106 years; 57% were female, and 78% were white. Patients admitted from a nursing home constituted 14.6% of the sample, and 9.3% of all patients had a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order written. Altered mental status was recorded in 13%. Older patients and those admitted from a nursing home or who had a DNR order were at increased risk of death (Table 1)A history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was present in 45% of patients; coronary artery disease in 26%; congestive heart failure, 24%; diabetes, 20%; cerebrovascular disease, 15%; and chronic renal failure, 4%. A history of chronic liver disease, malignancy, alcohol abuse, splenectomy, or malnutrition was found for fewer than 4% of patients. Twenty-one patients (2.1%) were suspected of having aspiration pneumonia.

Table 1.

Patient Sociodemographic Characteristics and Risk of Mortality

| Variable * | Patients, n(%)(n= 1,024) | Mortality, n(%) | Odds Ratio †(95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 803 (78.4) | 43 (87.8) | 2.0 (0.85, 4.8) |

| Nonwhite | 221 (21.6) | 6 (12.2) | 1.0 |

| Female | 581 (56.7) | 30 (61.2) | 1.2 (0.68, 2.2) |

| Male | 443 (43.3) | 19 (38.8) | 1.0 |

| Age, years | |||

| <65 | 384 (37.5) | 3 (6.1) | 1.0 |

| 65–69 | 82 (8.0) | 2 (4.1) | 3.18 (0.5, 19.2) |

| 70–79 | 257 (25.1) | 13 (26.5) | 6.77 (1.9, 24.1) |

| 80–89 | 224 (21.9) | 22 (44.9) | 13.8 (3.9, 49.3) |

| ≥90 | 77 (7.5) | 9 (18.4) | 16.8 (4.4, 63.4) |

| From nursing home | |||

| Yes | 146 (14.5) | 22 (45.8) | 5.6 (3.3, 9.6) |

| No | 858 (85.5) | 26 (54.2) | 1.0 |

| Missing values = 20 | |||

| Do not resuscitate | |||

| Yes | 95 (9.3) | 22 (44.9) | 10.1 (6.0, 16.8) |

| No | 926 (90.7) | 27 (55.1) | 1.0 |

| Missing values = 3 | |||

Missing values included in referent category for calculation of odds ratio.

Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio.

Significant at α = 0.05.

Ninety-nine percent of the patients had a chest x-ray report available for abstraction. The admission chest x-ray was interpreted as showing an acute infiltrate in 791 patients (74%), and 2 of these (0.2%) were reported as demonstrating an abscess. The median as well as the modal number of lobes involved with the infiltrate was one, and a pleural effusion was noted for 11% of patients.

The risk of mortality associated with the individual risk factors included in the PSI is shown in Table 2) . The PSI risk factors individually associated with increased risk of death included lower systolic blood pressure; increased respiratory rate; altered mental status; and the presence of acidosis, lower hematocrit, elevated blood urea nitrogen, hyponatremia, and a history of either congestive heart failure or cerebrovascular disease (Table 2). The PSI covariates that were associated with increased risk of death but whose 95% confidence intervals included 1 were elevated temperature and pulse rate, hypoxia, hyperglycemia, chest x-ray evidence of a pleural effusion, and the presence of coronary artery disease.

Table 2.

Mortality Risk Factors Used in the Pneumonia Severity Index

| Variable * | Patients, n(%)(n= 1,024) | Mortality, n(%) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| >80 mm Hg | 1,001 (97.8) | 45 (91.8) | 1.0 |

| 71–80 mm Hg | 15 (1.5) | 3 (6.12) | 5.3 (1.4, 19.5) |

| 61–70 mm Hg | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | —‡ |

| ≤60 mm Hg | 1 (0.1) | 1 (2.04) | —‡ |

| Missing values = 2 | |||

| Temperature | |||

| <95°F | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | —‡ |

| 95–105°F | 1,005 (98.1) | 48 (98.0) | 1.0 |

| 105°F | 14 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1.5 (0.2, 12.0) |

| Missing values = 4 | |||

| Pulse rate | |||

| <150 beats/min | 1,004 (98.1) | 47 (95.9) | 1.0 |

| ≥150 beats/min | 19 (1.9) | 2 (4.1) | 2.4 (0.6, 10.2) |

| Missing values = 1 | |||

| Respiratory rate | |||

| <30 breaths/min | 770 (75.3) | 23 (46.9) | 1.0 |

| ≥30 breaths/min | 252 (24.7) | 26 (53.1) | 3.8 (2.2, 6.5) |

| Missing values = 2 | |||

| Altered mental status | |||

| Yes | 135 (13.2) | 14 (28.6) | 2.8 (1.5, 5.4) |

| No | 889 (86.8) | 35 (71.4) | 1.0 |

| pH (normal mental status) | |||

| 7.35 | 502 (49.0) | 21 (42.9) | 1.0 |

| 7.2–7.35 mmol/L | 28 (2.7) | 4 (8.2) | 3.7 (1.2, 11.2) |

| <7.2 mmol/L | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.02) | 5.6 (0.6, 50.4) |

| Missing values = 354 | |||

| pH (altered mental status) | |||

| <7.35 | 75 (7.3) | 9 (18.4) | 1.0 |

| 7.2–7.35 mmol/L | 6 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | —‡ |

| <7.2 mmol/L | 4 (0.4) | 2 (4.1) | 22.3 (3.1, 161) |

| Missing values = 50 | |||

| Hematocrit | |||

| <0.29 SI units | 973 (96.2) | 44 (89.8) | 1.0 |

| ≤0.29 SI units | 38 (3.8) | 5 (10.2) | 3.2 (1.2, 8.7) |

| Missing values = 13 | |||

| PO2 | |||

| >60 mm Hg | 418 (67.3) | 25 (67.6) | 1.0 |

| ≤60 mm Hg | 203 (32.7) | 12 (32.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.6) |

| Missing values = 403 | |||

| BUN (normal mental status) § | |||

| <10.7 mmol/L | 232 (22.7) | 4 (8.2) | 1.0 |

| 10.7–17.5 mmol/L | 304 (29.7) | 4 (8.2) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.7) |

| <17.5 mmol/L | 334 (32.6) | 27 (55.1) | 4.7 (1.7, 11.7) |

| Missing values = 19 | |||

| BUN (altered mental status) § | |||

| <10.7 mmol/L | 20 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1.0 |

| 10.7–17.5 mmol/L | 43 (4.2) | 3 (6.1) | 4.0 (0.9, 17.5) |

| >17.5 mmol/L | 70 (6.8) | 10 (20.4) | 8.9 (0.1, 27.7) |

| Missing values = 2 | |||

| Glucose | |||

| ≤13.9 mmol/L | 955 (93.3) | 44 (89.8) | 1.0 |

| >13.9 mmol/L | 69 (6.7) | 5 (10.2) | 1.6 (0.6, 4.2) |

| Missing values = 21 | |||

| Albumin | |||

| >2.59 g/dL | 798 (91.9) | 38 (92.7) | 1.0 |

| ≤2.59 g/dL | 70 (8.1) | 3 (7.3) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.9) |

| Missing values = 156 | |||

| Sodium | |||

| ≥130 mEq/L | 970 (96.8) | 44 (89.8) | 1.0 |

| >130 mEq/L | 32 (3.2) | 5 (10.2) | 4.0 (1.6, 10.1) |

| Missing values = 22 | |||

| Pleural effusion | |||

| Yes | 895 (89.0) | 41 (85.4) | 1.4 (0.61, 3.2) |

| No | 111 (11.0) | 7 (14.6) | 1.0 |

| Missing values = 18 | |||

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| Yes | 242 (23.6) | 25 (51.0) | 3.6 (2.1, 6.3) |

| No | 782 (76.4) | 24 (49.0) | 1.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||

| Yes | 151 (14.8) | 17 (34.7) | 3.3 (1.8, 6.0) |

| No | 873 (85.2) | 32 (65.3) | 1.0 |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Yes | 264 (25.8) | 15 (30.6) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) |

| No | 760 (74.2) | 34 (69.4) | 1.0 |

| Chronic liver disease | |||

| Yes | 10 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | —∞ |

| No | 1,014 (99.0) | 49 (100) | 1.0 |

| Current malignancy | |||

| Yes | 38 (3.5) | 6 (12.2) | 4.4 (1.9, 10.3) |

| No | 988 (96.5) | 43 (87.8) | 1.0 |

Missing values included in referent category for calculation of odds ratio.

Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio.

No estimate presented for categories with 5 or fewer subjects.

BUN indicates blood urea nitrogen.

Calibration and Discriminatory Ability of the Pneumonia Severity Index

The mean (SD) PSI score, which can be interpreted as the individual patient’s probability of death, was 0.28 (0.14) among patients who died and 0.11 (0.12) among survivors (p < .001). We assessed the discriminatory ability of the PSI in our group of patients using an ROC curve. The area under this curve for the PSI was 0.847, significantly different from 0.5 (p < .001), which indicates good ability to discriminate patients who die from those who do not, similar to the results of Fine at al.8

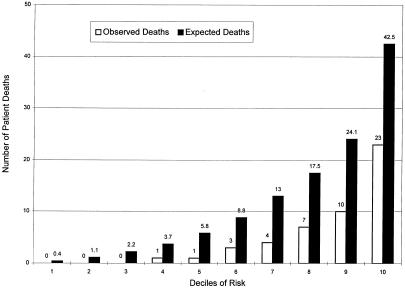

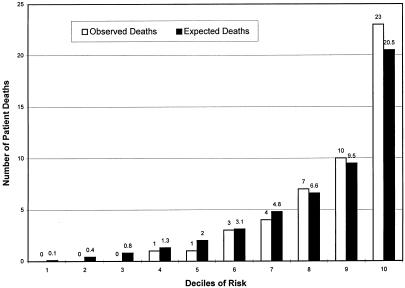

When we divided the patients into deciles based on predicted risk as suggested by Hosmer and Lemeshow, the PSI score was a strong predictor of mortality, with numbers of deaths increasing for each increment in PSI (p < .001) (Fig. 1).11 However, when we compared the number of predicted deaths with the observed number in the upper six deciles for which the expected number of deaths exceeded 5, the tendency of the PSI to overpredict deaths was present in all categories (Fig. 1), with 119 predicted deaths compared with 49 observed, indicating poor calibration (p≤ .001). Poor calibration, as reflected in a tendency to overpredict deaths, indicated a need to recalibrate the PSI before using it with our group of patients. We recalibrated the PSI by fitting a logistic model, as described in the Methods section. The estimated intercept was −1.0 (SD = 0.24), and the estimated coefficient of the transformed PSI score was 1.08 (SD = 0.15), not significantly different from 1.0 (p>.30). After recalibrating and forcing the coefficient of the transformed PSI score to be 1, the number of predicted deaths in the upper three deciles of risk for which the expected number of deaths exceeded 5 agreed closely with the number observed (p= .5) (Fig. 2). The discriminatory ability of the model was little affected, with the area under the ROC curve remaining unchanged at 0.847.

FIGURE 1.

Pneumonia severity index related to mortality.

FIGURE 2.

Recalibrated pneumonia severity index related to mortality.

For further comparison to the original report of the PSI, we divided the patients into five groups based on percentiles of the PSI, using the same percentiles described by Fine et al.8 Interestingly, the predicted mortality for each category of risk was similar to that which Fine at al.8 predicted for their derivation cohort (Table 3) We also found a strong trend of increasing mortality with increasing PSI, but the PSI overpredicted mortality for each risk group. These results are, again, consistent with good discriminatory ability but poor calibration. After recalibration, the observed and expected numbers agreed more closely. For example, in the largest (severity class 2), the observed mortality was 1.8%, that predicted based on the PSI before recalibration was 6.0%, whereas that predicted by the recalibrated PSI was 2.1%.

Table 3.

Observed and Expected Deaths, Across Five Risk Groups *

| Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity Class | Patients, n | Observed Mortality, % | Predicted Mortality, †% | Originally PredictedMortality, ‡% |

| 0 | 14 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 123 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 585 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 5.0 |

| 3 | 290 | 13.1 | 26.0 | 23.1 |

| 4 | 12 | 0.0 | 64.0 | 66.0 |

Risk groups were defined by percentiles of PSI, so that relative proportions of patients in each group would be the same as those used by Fine et al.8

Mortality predicted by the PSI for our patients.

For comparison, mortality was predicted by the PSI by Fine et al., 8 for their validation cohort, by severity class.

DISCUSSION

The utility of a standard prediction model like the PSI is uniformity of measurement across populations and studies. For example, Iezzoni and her colleagues used two clinical indices based on the MedisGroups and a modification of the APACHE III scoring systems and three administrative models to predict severity of illness in patients with CAP.4,18 They found that as many as 25% of patients were assigned very different estimates of risk in pairwise comparisons among combinations of the different scores.18 Thus, different severity indices used to adjust mortality, or other outcomes of care of CAP among hospitals (or other patient groupings), might result in different conclusions.

Iezzoni et al. found the greatest agreement between the two clinical scores.18 While clinically based severity-of-illness measures may be superior for estimating risk of mortality in patients with CAP, are there reasons in addition to its clinical basis to prefer the PSI over previously studied indices like the MedisGroups and APACHE III scores? The PSI has two features that recommend it as a strong candidate for a standardized prediction rule for CAP. First, it is specific for CAP, and some evidence suggests that disease-specific indices may provide more accurate estimates of risk than do global severity indices.19,20 Second, the parameters for the PSI that allow calculation of patient-specific risk estimates, unlike those for the proprietary models, have been published, allowing independent use of the Fine model.8

Other desirable characteristics of the PSI are that it directly yields a patient-specific estimate of mortality risk, uses information readily available for most patients, and uses predictors measured at or near the time of admission. Although we found that some of the patient attributes in the PSI were not strong risk factors in our population, all of the risk estimates were consistent with those reported for the PSI. It is important to note that the absence of statistical significance for individual risk factors does mean that the model is not useful in our population. It is not unexpected that risk factors for death in patients with CAP will differ among studies.21 Differences may arise from many sources including study design, methods of patient enrollment and follow-up, selection of prognostic factors measured and methods of measurement, definitions of outcomes, source of patients, and sample size.

Before the PSI can find wide use, it is important to demonstrate that it is a reliable and valid prediction rule in populations different from that in which it was derived.13 This need arises from the observation that prediction rules frequently fail to perform as well as reported when used in new populations. This problem was previously identified when applying cardiovascular risk prediction rules across populations. An early study by Kleinbaum et al. found that the association of four risk factors with incidence among African Americans in Evans County, Georgia, was similar to that among other Americans.22 When they applied a logistic regression model developed in a cohort of white males to this population, the mortality for African-American males was overpredicted. Recalibration of the model for white males led to substantially improved agreement between observed and predicted risk.22 Similarly, Keys et al. found that although estimates of relative risk for coronary heart disease attributed to different factors were comparable for American and European cohorts in the Seven Countries Study, absolute risks were underestimated when European data were used to predict U.S. mortality.23

Later studies of the widely used cardiovascular risk prediction model from the Framingham Heart Study have found a need to recalibrate the risk logistic in some, but not all, populations. Laurier et al. applied data from the Framingham (Mass.) study to predict the risk of cardiovascular disease to a French cohort and found that it predicted a twofold higher coronary heart disease risk than that calculated from a model developed in the French cohort.24 However, after adjustment of the basal risk, which is similar to recalibration, agreement substantially improved. This phenomenon has been termed “the failure of cross-cultural risk prediction.”24 In contrast, application of the Framingham model to U.S. populations from the Western Collaborative Group Study and to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study I (NHANES I) found estimates of absolute risk comparable to those observed in the studies.25,26

Consistent with these cardiovascular disease studies, we found that the predictive validity of the PSI to separate patients into groups based on risk in a new population was high as assessed by the area under the ROC curve.14,15,27 We also found that the calibration of the PSI was poor in our study and that the PSI predicted about 2.4 times more deaths than actually occurred in our population. The lower-than-predicted absolute mortality in our patient population is probably due, at least in part, to a real variation in mortality by time and place; the mortality of 13% in the derivation cohort and 11% in the validation cohort in the study of Fine et al., 8 was substantially higher than that of 4.8% observed in our population. The inability of the severity index to account for the lower mortality in the Georgia patients presumably reflects the presence of other, unmeasured factors. These factors potentially include regional and secular differences in admission criteria, differences in treatment and antibiotic usage, differences in available technology, and differences in disease and patient prognostic factors. The overestimation of risk, in turn, led to biased estimates of risk-adjusted mortality comparisons between the Fine derivation population and the community hospital sample, but not within the study population itself. As it is not possible to tell when recalibration may be necessary and the misestimation of risk that may result from a poorly calibrated risk predictor may lead to biased inferences about hospital-specific risks and hospital-to-hospital variations in mortality outcome, it seems prudent to recommend that calibration be assessed on a study-by-study basis.

Several approaches have been suggested to recalibrate prediction rules. These include the empirical indexing described above, revision using Bayes theorem, and application of multiattribute utility theory.28,29 The recalibration in our study was easily accomplished by simple logistic regression. Although not the main emphasis of their work, the approach used by Iezzoni 9 and Iezzoni et al.12 to compare different risk adjusters effectively recalibrated each score. The resulting estimates of absolute risk led to aggregate agreement between observed and expected deaths, for all hospitals and patients combined.

A modified PSI published by Fine et al. illustrates the evolving nature of risk prediction for CAP.30 The revised PSI was used to derive a simple predictor score for clinical risk stratification.30 Calculations from our study data (not shown) support the use of the modified PSI across populations to predict risk as a ranked measure in that mortality increased substantially across risk classes defined by the point system. However, mortality in our cohort was lower in every risk class when compared with rates observed by Fine et al. in their derivation cohort (p < .001). Since the modified PSI was not published with coefficients, we could not evaluate its calibration in detail, but would caution that our results suggest that, when applied to patients with CAP from a different population, mortality within risk classes may differ from that in the cohorts analyzed by Fine et al.

A limitation of our study is that the inclusion criteria we used were not identical to those used by Fine et al.8 For example, we required mention of pneumonia as a primary diagnosis in the medical record within 12 hours of admission as well as a principal ICD-9 pneumonia code, whereas Fine et al. only required an ICD-9 diagnosis. Furthermore, unlike Fine et al., 8 we excluded deaths that occurred with 4 hours of admission. However, only two such patients were excluded. Moreover, Fine et al. included some pneumonia of fungal and “miscellaneous” etiologies, which we did not include. Because the frequency of specific classes of pneumonia was not published, we could not assess directly the potential impact of these differences in inclusion criteria. However, the patients we did include accounted for about 97% of the patients in the categories used by Fine et al., and the differences in inclusion criteria probably do not explain the tendency of the PSI to overestimate mortality in our population.31

These variations between the two sets of inclusion criteria reflect the contingencies of our quality improvement study. If the differences in inclusion criteria did, in fact, bias our sample cohort toward healthier patients, this could account for the overestimation of death and poor calibration of the PSI when applied in our study. However, our results under this assumption continue to support the conclusion that, while the PSI may be sensitive to patient selection criteria that are not accounted for by the PSI, recalibration is needed. Further, the good discriminatory ability and predictive consistency of the PSI in the face of variation of inclusion criteria support the potential for broad application of the index.

In conclusion, we found the PSI to be a reliable and valid disease-specific measure of severity of illness in patients with CAP that is transportable across populations. Although the original PSI overestimated absolute risk of death in our population, recalibration corrected this problem. We described a simple, data-based approach to recalibration, which corrected the overestimation of absolute risk of death in our population.

Acknowledgments

The analyses upon which this publication is based were performed under contract 500-96-P704, entitled, “Operation Utilization and Quality Control Peer Review Organization (PRO) for the State of Georgia,” sponsored by the Health Care Financing Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. This article is a direct result of the Health Care Quality Improvement Program initiated by the Health Care Financing Administration, which has encouraged identification of quality improvement projects derived from analysis of patterns of care, and therefore required no special funding on the part of this Contractor. Ideas and contributions to the authors concerning experience in engaging with issues presented are welcomed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicare Hospital Mortality Information. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275:134–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert K, Fine MJ, et al. Assessing prognosis and predicting patient outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect. 1994;9:140–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iezzoni LI, Shwartz M, Ash AS, Mackiernan YD, et al. Using severity measures to predict the likelihood of death for pneumonia inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02603481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1418–26. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr BM, Sloman AJ, Fisch MJ, et al. Predicting death in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:428–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewster AC, Karlin BG, Hyde LA, et al. MEDISGRPS: a clinically based approach to classifying hospital patients at admission. Inquiry. 1985;12:377–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine MJ, Hanusa BH, Lave JR, et al. Comparison of a disease-specific and a generic severity of illness measure for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:359–68. doi: 10.1007/BF02599830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iezzoni LI, et al. The risks of risk adjustment. JAMA. 1997;278:1600–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.19.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine MJ, Singer DE, Hanusa BH, Lave JR, Kapoor WN, et al. Validation of a pneumonia prognostic index using the MedisGroups comparative hospital database. Am J. Med. 1993;94:153–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90177-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemeshow S, Le Gall JR, et al. Modeling the severity of illness of ICU patients. JAMA. 1994;272:1049–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iezzoni LI, Shwartz M, Ash AS, et al. Severity measurement methods and judging hospital death rates for pneumonia. Med Care. 1996;34:11–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, Goldman L, et al. Clinical prediction rules: application and methodologic standards. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:793–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ, et al. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iezzoni LI, et al. Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. Ann Arbor, Mich: Health Administration Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeger SL, Liang KY, et al. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iezzoni LI, Ash AS, Schwartz M, Daley J, Hughes JS, Mackierman YD, et al. Predicting who dies depends on how severity is measured: implications for evaluating patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:763–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg MS, et al. Biased estimates of expected acute myocardial infarction mortality using MedisGroups admission severity groups. JAMA. 1991;265:2965–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daley J, Jencks S, Draper D, Lenhart G, Thomas N, Walker J, et al. Predicting hospital-associated mortality for Medicare patients: a method for patients with stroke, pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure. JAMA. 1998;260:3617–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.24.3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houston MS, Silverstein MD, Suman VJ, et al. Risk factors for 30-day mortality in elderly patients with lower respiratory tract infection: community based study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2190–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Cassel JC, Tyroler HA, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk of coronary heart disease in Evans County, Georgia. Arch Intern Med. 1971;128:943–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keys A, Aravanis C, Blackburn H, et al. Probability of middle-aged men developing coronary heart disease in five years. Circulation. 1971;45:815–28. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurier D, Chau Pnp, Cazelles B, Segond P, et al. and the PCV-METRA Group. Estimation of CHD risk in a French working population using a modified Framingham model. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1353–64. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brand RJ, Rosenman RH, Sholtz RI, Friedman M, et al. Multivariate prediction of coronary heart disease in the Western Collaborative Group Study compared to findings of the Framingham Study. Circulation. 1976;53:348–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaverton PE, Sorlie PD, Kleinmen JC, et al. Representativeness of the Framingham risk model for coronary heart disease mortality: a comparison with a national cohort study. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:775–84. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Number 17. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1979. Reliability and validity assessment; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poses RM, Cebul RD, Collins M, Fager SS, et al. The importance of disease prevalence in transporting clinical prediction rules: the case of streptococcal pharyngitis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:586–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-4-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustafson DH, Fryback DG, Rose JH, et al. A decision theoretic methodology for severity index development. Med Decis Making. 1986;6:27–36. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8600600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine MJ, Aubile TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Hospital Discharge Survey. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 1998–1990. [Google Scholar]