Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the prevalence of unrecognized or unsuccessfully treated depression among high utilizers of medical care, and to describe the relation between depression, medical comorbidities, and resource utilization.

DESIGN

Survey.

SETTING

Three HMOs located in different geographic regions of the United States.

PATIENTS

A total of 12,773 HMO members were identified as high utilizers. Eligibility criteria for depression screening were met by 10,461 patients.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Depression status was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Depression screening was completed in 7,203 patients who were high utilizers of medical care, of whom 1,465 (20.3%) screened positive for current major depression or major depression in partial remission. Among depressed patients, 621 (42.4%) had had a visit with a mental health specialist or a diagnosis of depression or both within the previous 2 years. The prevalence of well-defined medical conditions was the same in patients with and patients without evidence of depression (41.5% vs 41.5%, p = .87). However, high-utilizing patients who had not made a visit for a nonspecific complaint during the previous 2 years were at significantly lower risk of depression (13.1% vs 22.4%, p < .001). Patients with current depression or depression in partial remission had significantly higher numbers of annual office visits and hospital days per 1,000 than patients without depression.

CONCLUSIONS

Although there was evidence that mental health problems had previously been recognized in many of the patients, a large percentage of high utilizers still suffered from active depression that either went unrecognized or was not being treated successfully. Patients who had not made visits for nonspecific complaints were at significantly lower risk of depression. Depression among high utilizers was associated with higher resource utilization.

Keywords: depression, health screening, primary care, health care utilization

Depressive illness is related to significantly increased morbidity and mortality.1 In addition to its tremendous human costs, depression is associated with huge economic costs. Depressed patients make more office visits, and more telephone calls to their physicians, have more medical tests and evaluations, take more medications, and are more likely to be hospitalized for medical disorders than are nondepressed patients.2–4 Not surprisingly, therefore, depression is particularly prevalent among “high utilizers” of medical care resources, of whom as many as 40% have been found to have a current depressive illness.5

Depression itself would be expected to contribute to a greater use of health care services simply because its evaluation and treatment takes time and costs money.6 However, several reports have shown that even after efforts to control for age and preexisting medical comorbidity, patients with depression receive two to four times as much nonpsychiatric medical care as do patients without depression.4,7–14 Whether treatment of depression can reduce this “excess” nonpsychiatric medical care remains an intriguing question.15

Treatment, however, must start with identification. Previous studies have shown that at least half of patients with active depression seen by primary care physicians remain undiagnosed.16–20 Recognition of depression among high utilizers of medical care may be even more challenging because the effects of medical illness can overlap with those of depression, and many patients have somatic symptoms rather than classic symptoms of depression.21–24

Given the link between depression and high utilization of medical care, more information is needed about the potential for depression screening among high utilizers of care to uncover unrecognized or unsuccessfully treated depression. More data are also needed to understand the specific health and resource-utilization burdens associated with depression among this patient group. In a time of increasing pressure to control health care costs, these data will help us to assess the contribution of depression to health care costs and identify high-yield targets for depression screening among patients with high medical utilization—patients for whom the cost of successful depression treatment might be offset by savings from the reduction of nonessential medical services.

This report is based on data gathered as part of the CARE study, a randomized trial examining the impact of population-based screening and treatment for depression among high utilizers of general medical care. In this report, we use data from the screening phase of the study to examine the following among this group of patients: (1) the prevalence of unrecognized or unsuccessfully treated depression; (2) the association between depression and general medical illness; and (3) the relation of depression to resource utilization.

METHODS

HMO Sites and Mental Health Services

This study was conducted from October 1995 through December 1996 at three HMOs operating in different regions of the United States: DeanCare HMO in Wisconsin; Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (GHC) in the state of Washington; and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HPHC) in New England. All three HMOs are large mixed-model managed care organizations. The participating physician practices were in a group-model HMO at DeanCare, and in staff-model health centers within GHC and HPHC. DeanCare serves suburban and rural communities, and its primary care physician panel consists of a roughly even mixture of family physicians and internists. The participating staff-model centers of GHC mostly serve suburban communities, and their primary care physicians are family physicians. The participating health centers of HPHC serve both urban and suburban members with a primary care physician panel composed exclusively of general internists.

At the time of this study, mental health services for the members of all three HMOs were provided inside the health plan by mental health clinicians directly employed by or affiliated with the HMO. DeanCare provided most of its specialty mental health care in a main clinic; thus, some practices did not offer on-site mental health. Most, but not all, DeanCare members were able to self-refer to mental health services, with a yearly outpatient limit of $1,800 and no copayments for visits. Members of GHC received specialty mental health services primarily at specialty clinics separate from primary care office buildings. All GHC members could self-refer to mental health services, and typically were covered for 20 psychotherapy visits per year, subject to copayments of $10 to $20 per visit. Members of HPHC were able to visit specialty mental health departments within each health center. All HPHC members could self-refer to mental health services, for which typical coverage included 20 outpatient visits per year, with copayments of $5 for the first eight visits, rising to $35 thereafter. Neither GHC nor HPHC placed any limit on visits for medication management.

Definition and Identification of Eligible High Utilizers

As part of the larger CARE study, each health plan examined the membership records of all its enrollees to identify patients who met each of the following eligibility criteria: aged 25 to 63 years (inclusive) at time of sampling; continuous HMO coverage and drug coverage for the preceding 2-year period with a maximum gap of 45 days; and no point-of-service benefit.

Among members meeting all of the age and insurance eligibility criteria, we used the computerized utilization databases of each HMO to identify those members who ranked in the top 15% within their HMO in the number of ambulatory visits during each of the previous 2 years. The number of outpatient visits was selected as our criterion because it correlates highly with overall costs and would be much easier to use in everyday practice as the basis for a depression screening program than would a measure of overall costs.25 We included in our visit counts all face-to-face ambulatory visits except house calls, visits to an emergency department, a mental health provider, or an optometrist, and visits for prenatal or obstetric care, physical or occupational therapy, radiographic studies, or allergy injections.

To exclude patients whose high utilization might reflect a short-term fluctuation due to a single episode of serious illness, we limited our final selection to members who made the list of the top 15% in visits independently and consecutively in both of the preceding 2 years. Each HMO determined its own threshold number of visits in each year that would qualify a member as a high utilizer.

Because the goal of the CARE study was to identify HMO members who were not in active mental health treatment and were otherwise suitable candidates for a primary-care-based treatment program for depression, we excluded from depression screening high utilizers who met any of the following six criteria: (1) one-on-one visit with a specialty mental health provider (psychiatrist, psychologist, master's level therapists only) within the previous 120 days; (2) use of an antidepressant within the previous 90 days, with at least 30 days of an adequate dose for treatment of depression based on American Psychiatric Association guidelines26; (3) a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder within the previous 2 years; (4) a diagnosis of alcohol or substance abuse within the previous 120 days; (5) any diagnosis of a life-threatening medical disorder such as malignant brain tumor, malignant lung cancer, metastatic stomach cancer, primary hepatic malignancy, metastatic esophageal cancer, pancreatic carcinoma, or acute leukemia; and (6) any direct family member working for the HMO.

All eligibility and exclusion criteria were determined periodically for all HMO patients over a time window of 6 to 9 months at each HMO. Any member within participating practices who satisfied the eligibility criteria during the time window became eligible to be screened for depression.

Depression Screening

An invitation letter describing the study was mailed to eligible HMO members and was followed within 7 to 10 days by a telephone call from a trained telephone screener who sought consent for participation. The telephone screening included the SF-20 Quality of Life Questionnaire27 and the mood episodes module from a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition(SCID).28

The SCID is a semistructured interview designed for use by an experienced clinician in diagnosing mental disorders according to DSM-IV criteria. Agreement between results gained from telephone and in-person administration of the SCID has been found to be excellent.29 To maximize interrater reliability, the SCID was modified in the following ways for use in the current study: open-ended questions were reworded and replaced by more specific, closed-ended questions; only the current and past major depressive episode items were asked; and questions regarding past episodes of depression were restricted to the previous 2 years.

Screeners received intensive training coordinated across all three HMOs to maximize accuracy and consistency in the administration of the SCID. Throughout the CARE study, all screeners had ongoing training sessions consisting of SCID interviews done live during group telephone calls, with feedback from an expert clinician.

Patients were considered to screen positive for depression if their SCID results indicated current major depression or major depression in partial remission. Partial remission was defined as meeting the following criteria: having had a full episode of major depression in the past 2 years; not meeting full criteria for major depression in the past month; and currently having at least two of the nine symptoms of depression listed in the SCID. Patients in partial remission were considered to screen positive because they have the potential to benefit both clinically and functionally from depression treatment, especially if their depressive symptoms are at least moderately severe.30

Outcome Measures

We obtained data on age and sex of the population from the enrollment and membership databases maintained by the three HMOs. Inpatient and outpatient resource utilization data were obtained from the claims, encounter, or automated medical record data systems of the three HMOs.

Statistical Analyses

For each of the outcome variables, the patients were compared by results of depression screening using least squares with standard errors corrected for heteroscedasticity across depression-screening categories using the Huber-White correction or sandwich estimator.31,32

Multiple comparisons were dealt with in two ways. First, p values for individual outcomes were assessed by using Bonferonni bounds, which divide the standard critical p value of .05 by the number of comparisons.33 Second, we used an overall F statistic for the comparison of all outcome variables in a table across depression screening categories by using seemingly unrelated regression.34 In this case, we estimated a system of simultaneous equations, with one equation for each of the outpatient characteristics (as dependent variables) and indicators for depression categories (as independent variables). Overall F statistics were calculated for the coefficients on all of the indicator variables in all of the equations being simultaneously 0. For each of the tables that follow, one reaches the same conclusion with both of these approaches.

RESULTS

Identification of High Utilizers

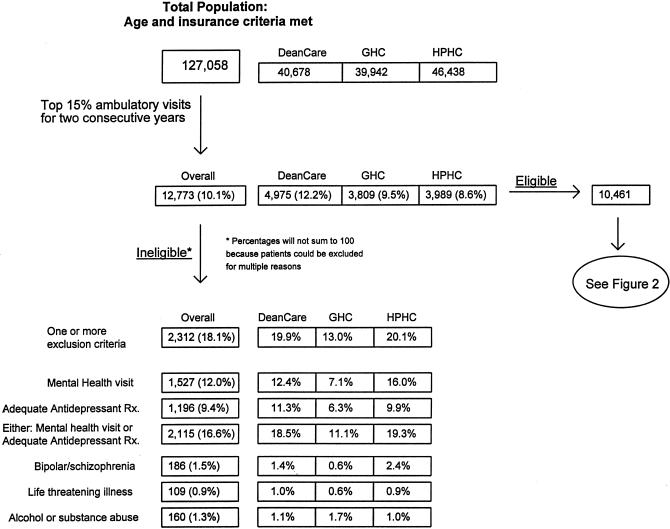

Seven or more ambulatory visits in each of the two previous years were necessary for a patient to be identified as a high utilizer at both DeanCare and GHC; at HPHC, the threshold was eight or more visits in each of the previous years. Out of a population of 127,058 members from the participating clinics across the three HMOs who met age and insurance eligibility criteria, 12,773 (10.1%) reached visit totals qualifying them as high utilizers.

Of all high utilizers identified, 2,312 (18%) were subsequently excluded from eligibility for depression screening. Figure 1 displays the flow of patient identification and evaluation for screening eligibility across all three HMOs. Patients at GHC were significantly less likely than those at DeanCare or HPHC to be ineligible for depression screening (13% vs 20% and 21%, p = .001). As shown in Figure 1, most of this difference was due to a lower rate of exclusion among GHC patients for evidence of probable preexisting treatment for depression: a visit to a specialty mental health clinician within the previous 120 days or receipt of an antidepressant prescription of adequate dose and duration during the previous 90 days.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of high utilizers and application of study exclusion criteria.

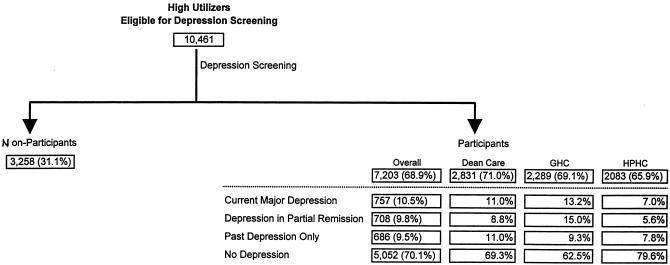

Among the 10,461 patients who were eligible to be screened for depression, the average age was 47 years, and 67% were women. The average total number of ambulatory office visits for these high utilizers in the 2 preceding years was 24.3 (SD = 10.7). Of all eligible high utilizers, 7,203 (69%) were contacted, agreed to participate, and subsequently completed the screening. Figure 2 continues the study eligibility diagram from Figure 1 and shows the results of depression screening. Of those eligible for screening, 19% declined to be interviewed, and another 12% were unreachable or were ineligible owing to language, insurance coverage, or other reasons. Nonparticipants on average were only slightly younger (46 vs 47 years, p < .001), were less likely to be female (63% vs 69%, p < .001), and also had relatively similar numbers of ambulatory visits per year as participants (24.1 vs 24.8, p < .001). In addition, nonparticipants and participants had the same prevalence within the past 2 years of having visited a specialty mental health clinician (19%) or having received a diagnosis of depression (13%). This suggests that there should have been little difference in the prevalence of undetected depression between participating and nonparticipating high utilizers.

FIGURE 2.

Results of depression screening.

Prevalence of Depression

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of depression among the high utilizers completing depression screening. Overall, 1,465 patients (20%) had significant depressive illness (current major depression or major depression in partial remission). The highest proportion of patients screening positive for depression was at GHC (28.2%). Of high utilizers at DeanCare, 19.8% screened positive; HPHC had the lowest percentage of high utilizers who screened positive (12.6%) (p < .001 for all comparisons).

Even though patients had been excluded from screening if they had a visit with a specialty mental health provider within the previous 120 days and/or at least 30 days of an adequate dose of an antidepressant within the previous 90 days, we still found that for many patients screening positive for depression there was evidence of recognition of depression or other mental health problems within the previous 2 years. Among screen-positive patients, 469 (32.0%) had been seen by a specialty mental health provider and 396 (27.0%) had been given a diagnosis of depression. All told, 621 (42.4%) of the screen-positive patients had one or both of these indicators of prior recognition.

Demographics and Medical Comorbidities

Because patients with either current major depression or depression in partial remission are candidates for diagnosis and treatment, we combined these two categories to evaluate the demographics and medical comorbidities associated with screening positive for depression.

The average age of patients who screened positive for depression was lower than that of other patients (45.4 vs 47.8 years, p < .001), and a slightly greater proportion were female (71.6% vs 68.8%, p = .03). Depression screening results were not found, however, to be highly associated with the likelihood of having any common, well-defined chronic medical condition (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Well-Defined Medical Comorbidities Among High Utilizers of Medical CareGrouped by Depression Screening Results*

| Clinical Comorbidity | Depression Screen-Positive, %(95% CI) (n = 1,465) | Depression Screen-Negative, %(95% CI) (n = 5,738) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIDS | 0.8 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | .266 |

| Asthma | 15.5 (13.6, 17.3) | 13.9 (13.0, 14.7) | .026 |

| Cancer | 7.4 (6.1, 8.8) | 8.5 (7.7, 9.2) | .149 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.6 (0.9, 2.2) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | .879 |

| Chronic lung disease | 4.8 (3.7, 5.9) | 3.6 (3.2, 4.1) | .049 |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | .779 |

| Diabetes | 11.8 (10.2, 13.5) | 13.0 (12.1, 13.9) | .244 |

| Heart failure | 2.7 (1.9, 3.6) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.0) | .035 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 6.7 (5.4, 8.0) | 7.2 (6.5, 7.8) | .590 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.2 (3.2, 5.3) | 4.2 (3.6, 4.7) | .809 |

| One or more | 41.5 (39.0, 44.0) | 41.5 (40.3, 42.8) | .872 |

| Two or more | 10.9 (9.3, 12.5) | 10.2 (9.4, 11.0) | .470 |

Rates are shown with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in parentheses. Individual p values and 95% CIs are not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The nominal or uncorrected p value corresponding to the Bonferroni bound for α = .05 is .05/12 = .0042. Depression screen-positive indicates current major depression or major depression in partial remission; depression screen-negative, history of past depression only or no history of depression.

Of 1,465 patients who screened positive for depression, 608 (41.5%) had a visit within the previous 2 years for at least one chronic medical condition. Patients who screened negative for depression had the same rate of medical comorbidity (41.5%, p = .87). The difference between the groups screening positive and negative, when compared globally across all the diagnoses in Table 1, nearly reached conventional significance (F [12, 86,388] = 1.69, p = .06), but most differences in rates of individual diagnoses between the high utilizers in both groups were very small and did not reach statistical significance.

Rates of visits for certain nonspecific complaints were very high among both patients screening positive and patients screening negative for depression (Table 2). These complaints, such as dizziness and fatigue, were chosen for analysis because they are common somatic symptoms of patients with anxiety and depression. Patients screening positive for depression had a higher rate of visits for these complaints, both overall and across all complaints as a group (F [12, 88,388] = 10.30, p < .0001). The most common nonspecific complaints for both groups were back or neck pain; other joint pain, stiffness, or myalgia; and abdominal pain. Almost all of these complaints were more common among patients who screened positive, including back and neck pain (41.6% vs 32.5%, p < .001), headaches (23.1% vs 17.4%, p < .001), and abdominal pain (30.9% vs 23.3%, p < .001).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Nonspecific Complaints Among High Utilizers of Medical CareGrouped by Results of Depression Screening*

| Nonspecific Complaint | Depression Screen-Positive, %(95% CI) (n = 1,465) | Depression Screen-Negative,%(95% CI) (n = 5,738) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 30.9 (28.6, 33.3) | 23.3 (22.2, 24.3) | <.001 |

| Back or neck pain | 41.6 (39.1, 44.1) | 32.5 (31.2, 33.7) | <.001 |

| Chest pain | 23.5 (21.3, 25.7) | 18.7 (17.7, 19.7) | .001 |

| Dizziness | 8.8 (7.4, 10.3) | 7.6 (6.9, 8.3) | .330 |

| Dyspnea | 8.7 (7.2, 10.1) | 7.6 (6.9, 8.3) | .303 |

| Fatigue | 12.6 (10.9, 14.3) | 9.7 (9.0, 10.5) | .004 |

| Gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, dyspepsia, etc.) | 12.6 (10.9, 14.3) | 9.2 (8.5, 10.0) | .009 |

| Headaches | 23.1 (20.9, 25.2) | 17.4 (16.4, 18.3) | <.001 |

| Joint pain/stiffness and other myalgia (fibrositis) | 42.1 (39.5, 44.6) | 31.3 (30.1, 32.5) | <.001 |

| Tachycardia/palpitations | 4.2 (3.1, 5.2) | 4.3 (3.8, 4.8) | .383 |

| One or more | 85.9 (84.1, 87.7) | 76.2 (75.0, 77.3) | <.001 |

| Two or more | 61.4 (58.9, 63.9) | 46.4 (45.1, 47.7) | <.001 |

Individual p values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The presence or absence of a visit for one of these nonspecific complaints within the previous 2 years could be used to dichotomize high utilizers into two groups with substantially different risks of active depression (Table 3) Of the 7,203 high utilizers, 1,576 (21.9%) did not have a visit for a nonspecific complaint. Among these patients, only 13% screened positive for depression, whether or not they had a chronic medical condition. Conversely, among the high utilizers who did have at least one visit for a nonspecific complaint, the rate of positive depression screens was 22% to 23%, whether or not the patients also had a chronic medical condition. Overall, the difference in positive depression screen rates between patients with and patients without nonspecific complaints was highly significant ( 22.4% vs 13.1%, p < .001).

Table 3.

Relation of Nonspecific Complaints, Chronic Medical Conditions, and the Risk of Active Depression

| NonspecificComplaint | Chronic MedicalCondition | DepressionScreen-Positive |

|---|---|---|

| + | + | 511/2,251 (22.7%) |

| + | − | 747/3,376 (22.1%) |

| − | + | 97/740 (13.1%) |

| − | − | 110/836 (13.2%) |

Resource Utilization

Table 4 displays differences in medical utilization among patients grouped according to the results of depression screening. Even after adjusting for the major medical comorbidities listed in Table 1, depression status was associated with a significant gradient in resource utilization. Patients screening positive for current major depression averaged more outpatient visits and had substantially higher rates of hospitalization and total hospital days over the preceding 2 years compared with patients with past depression only or with no history of depression. Patients with depression in partial remission had utilization rates more similar to those of patients with current major depression than to those of patients without evidence of depressive illness.

Table 4.

Medical Utilization of High Utilizers of Medical Care Grouped by Depression Screening Results*

| Utilization Measure | Current MajorDepression(n = 757) | Depression inPartial Remission(n = 708) | Past Depression Only(n = 686) | No Depression(n = 5,052) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory office visits | 12.9 (12.6, 13.3) | 12.7 (12.4, 13.0) | 12.3 (12.0, 12.5) | 11.8 (11.7, 11.9) | <.001 |

| Hospital days per 1,000 patients | 1,001 (847, 1,155) | 1,014 (850, 1,179) | 809 (671, 947) | 658 (600, 719) | <.001 |

| Percentage hospitalized | 17.8 (16.0, 19.7) | 18.6 (16.6, 20.7) | 16.0 (14.1, 18.0) | 12.9 (12.3, 13.6) | <.001 |

Annualized means are shown, followed by 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. All results are controlled for site, patient age and sex, and for the chronic diseases shown in Table 1.

All high utilizers demonstrated very high rates of hospital utilization, again in a pattern with the highest utilization among patients with most severe depressive illness. On an annualized basis, over 17% of patients with either current major depression or depression in partial remission were hospitalized each year. High utilizers with current major depression or depression in partial remission averaged approximately 1,000 hospital days per 1,000 members per year. In contrast, high utilizers with past depression only or no history of depression had only 809 and 658 total hospital days per 1,000 members per year, respectively (p < .001).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that many high utilizers of ambulatory health services in these three HMOs suffered from active depression that either went unrecognized or was not being treated successfully. Patients face few barriers to access to primary care and specialty mental health care in these three HMOs, and 16.5% of all high utilizers were already receiving adequate antidepressant treatment or being seen in mental health departments or both. Even after excluding these patients, however, our screening found that one of five remaining patients had evidence of current major depression or depression in partial remission.

Is this a relatively high prevalence of depression? Among general medical outpatients, most studies have found a prevalence of active depression of approximately 5% to 10%.8,20,23 One study found a prevalence of 18%.16 It is worth emphasizing, however, that we found a 20% level of active depression among high utilizers after excluding patients receiving adequate doses of antidepressants, patients with any record of substance abuse, and all patients being seen in mental health departments for any condition. Previous studies have not excluded these patients. In addition, at one of the study sites (DeanCare) we were able to determine the rate of depression among a random sample of patients who were not high utilizers, after applying the same exclusion criteria used in the high-utlizer sample. Among 512 screened who were not high utilizers, 55 (10.7%) had active depression, a rate much lower than the rate of 19.5% found among high utilizers at this site (p < .01). Our data therefore suggest that high utilizers are high-yield targets for depression screening and management.

Our data also suggest a practical way to focus depression screening even further. Over 20% of high-utilizing patients did not have at least one visit in the preceding 2 years for a symptom among our list of nonspecific complaints. These patients had rates of depression far lower than those of other high utilizers. Somewhat surprisingly, this relation appeared unaffected by the presence or absence of an underlying chronic medical condition. It seems reasonable, therefore, to suggest that physicians and health plans can increase the efficiency of depression screening by focusing their efforts among those high utilizers who have visits for nonspecific complaints.

Among the actively depressed high utilizers found in our study, nearly half had had depression or other mental health problems recognized and treated by their clinicians at some time in the previous 2 years. If these patients are considered together with the patients who were excluded from screening because of evidence of active mental health treatment, our data suggest that primary care physicians are, in fact, recognizing many of their depressed patients. For many high-utilizing patients, therefore, the key to improving clinical care lies not in uncovering hidden depression but in initiating and, even more importantly, in following through with effective treatment.

Our results confirm several previous reports of an association between depression and increased use of general medical services.7–14 High-utilizing patients who screened positive for depressive illness had more outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and total hospital days. The most substantial correlation between screening positive for depression and utilization in our data was for number of hospital days. Whether effective treatment for depression among high-utilizing patients is associated with a reduction in inpatient or outpatient resource utilization is a hypothesis under evaluation as part of the larger CARE study.

Our study is limited in its generalizeability by the sociodemographic features of the HMO patients studied. The HMO patient populations were composed of insured individuals under the age of 65 years, most with health insurance coverage through their employer or other groups. Whether the rates of depression we found would be comparable among high-utilizing patients from other populations is unknown. Similarly, each HMO in this study provided integrated mental health and general medical care. We cannot be certain how our results would generalize to health plans in which mental health care is “carved out” to a separate organization.

The prevalence of depression among screened patients was significantly higher at one of the HMOs (GHC) than at the other two. Although this finding could reflect differences in administration of the screening measure across sites, our reliability checks and detailed study of screening questionnaire performance across sites do not support this explanation. Epidemiologic surveys suggest that community prevalence of depression does not vary widely across regions of the United States,35 but differences in health systems or physician practices could still lead to differences in prevalence of depression among high utilizers of ambulatory services. Alternatively, the higher prevalence of depression in the GHC sample could reflect the smaller proportion of patients excluded at GHC because of current depression treatment. Assuming relatively equal rates of depression among patients at each HMO, this lower rate of exclusion at GHC would have left a higher proportion of patients with depression in the pool eligible for depression screening.

Given the high rates of depression we discovered among high-utilizing patients, our findings suggest that all these patients, whose ambulatory utilization can be easily identified by individual physicians as well as by HMOs, should be considered as high-yield targets for depression screening. Whether the depression identified among such high-utilizing patients is as amenable to treatment as depression in other cohorts is unknown. The higher resource utilization of these patients, however, may mean that the costs of depression screening and treatment might be offset by a decrease in the future resource utilization of successfully treated patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcome Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brody DS, Thompson TL, Larson DB, Ford DE, Katon WJ, Magruder KM. Recognizing and managing depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:93–107. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)00093-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katon W, Berg AO, Robins AJ, Risse S. Depression: medical utilization and somatization. West J Med. 1986;144:564–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:850–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990;12:355–62. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg P, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widmer RB, Cadoret RJ. Depression in primary care: changes in pattern of patient visits and complaints during a developing depression. J Fam Pract. 1978;7:293–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borson S, Barnes RA, Kukull WA, et al. Symptomatic depression in elderly medical outpatients, I: prevalence, demography, and health service utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:341–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267:1478–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon W, et al. The epidemiology of depression in medical care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1987;17:93–112. doi: 10.2190/xe8w-glcj-kem6-39fh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman MM. In: Affective disorders. In: Robins LN, Regier DA, editors. Psychiatric Disorders in America. New York, NY: Free Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nienaber NA, Musick BS, Tierney WM. Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:833–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning WG, Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med Care. 1992;30:541–53. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolinsky FD. Assessing the effects of the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of health on the use of health services. Social Q. 1982:191–7. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan CM, Kesterson JG, Tierney WM. Association of symptoms of depression with diagnostic test charges among older adults. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:426–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulberg HC, Burns BJ. Mental disorders in primary care: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and treatment research directions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler LG, Cleary PD, Burke Jd., Jr Psychiatric disorders in primary care: results of a follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:583–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ormel J, Koeter MWJ, van den Brink W, van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borus JF, Howes MJ, Devins NP, Rosenberg R, Livingston WW. Primary health care providers' recognition and diagnosis of mental disorders in their patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:317–21. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katon W, Kleinman A, Rosen G. Depression and somatization: a review, part I. Am J Med. 1982;72:127–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katon W, et al. Depression, somatic symptoms and medical disorders in primary care. Compr Psychiatry. 1982;23:274–87. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(82)90076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Muñoz RF, Yu-Wen Y. Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390170113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, et al. Discovering depression in medical patients: reasonable expectations. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:463–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFarland BH, Freeborn DK, Mullooly JP, Pope CR. Utilization patterns among long-term enrollees in a prepaid group practice health maintenance organization. Med Care. 1985;23:1221–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for major depressive disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:4(suppl):S1–26. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon GE, Revicki D, Von Korff M. Telephone assessment of depression severity. J Psychiat Res. 1993;27:247–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornwall PL, Scott J. Partial remission in depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:265–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. In: Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium in Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.White H. A heteroscedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test of heteroscedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller RG. Simultaneous Statistical Inference. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zellner A. An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J Am Stat Assoc. 1962;57:348–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the national comorbidity survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–86. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]