Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effects of a multimedia educational intervention about advance directives (ADs) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on the knowledge, attitude and activity toward ADs and life-sustaining treatments of elderly veterans.

DESIGN

Prospective randomized controlled, single blind study of educational interventions.

SETTING

General medicine clinic of a university-affiliated Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC).

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred seventeen Veterans, 70 years of age or older, deemed able to make medical care decisions.

INTERVENTION

The control group (n=55) received a handout about ADs in use at the VAMC. The experimental group (n=62) received the same handout, with an additional handout describing procedural aspects and outcomes of CPR, and they watched a videotape about ADs.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Patients' attitudes and actions toward ADs, CPR and life-sustaining treatments were recorded before the intervention, after it, and 2 to 4 weeks after the intervention through self-administered questionnaires. Only 27.8% of subjects stated that they knew what an AD is in the preintervention questionnaire. This proportion improved in both the experimental and control (87.2% experimental, 52.5% control) subject groups, but stated knowledge of what an AD is was higher in the experimental group (odds ratio = 6.18, p < .001) and this effect, although diminished, persisted in the follow-up questionnaire (OR = 3.92, p = .003). Prior to any intervention, 15% of subjects correctly estimated the likelihood of survival after CPR. This improved after the intervention in the experimental group (OR = 4.27, p = .004), but did not persist at follow-up. In the postintervention questionnaire, few subjects in either group stated that they discussed CPR or ADs with their physician on that day (OR = 0.97, p = NS).

CONCLUSION

We developed a convenient means of educating elderly male patients regarding CPR and advance directives that improved short-term knowledge but did not stimulate advance care planning.

Keywords: advance directives, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, life-sustaining treatments, medical decision making, patient education

The need for persons to reflect on their wishes for life-sustaining treatment and share those wishes with family or physician through advance directives or other means has been identified as important by the medical profession, bioethicists, and the federal government.1–4 As adults frequently overestimate their chance of surviving resuscitation,5 educational interventions have been developed to inform them of the generally poor outcomes of resuscitation in older adults.6–14 Some of these interventions have altered patient attitudes toward life-sustaining treatments and advance directives or improved knowledge in these areas.5,15–17

The outpatient clinic has been proposed as a good setting in which to discuss advance care planning.18 We hypothesized that a multimedia educational intervention would inform patients better than a simple handout about life-sustaining treatments, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and its outcomes, and advance directives, and might stimulate discussions between patients and their physician or family.

METHODS

Setting

This study was performed in the general medicine clinic of a university-affiliated Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) where primary care is delivered by attending physicians, physician assistants, and internal medicine residents.

Subjects

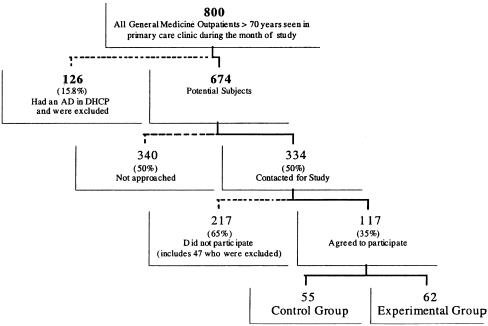

Figure 1 shows the eligible subject pool. An investigator (RY) attempted to contact each eligible patient in the clinic waiting area. Patients were considered cognitively eligible if, after hearing the explanation of the project, they demonstrated understanding of the project to the investigator's satisfaction. All subjects gave informed consent approved by the VAMC Subcommittee on Human Studies.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram portraying subject recruitment. AD indicates advance directive; DHCP, decentralized hospital computer program.

Interventions

Subjects were randomized into two groups based on their clinic half-day and the week of the month. Control subjects received a handout used infrequently at the VAMC, which described advance directives and how to make one, but does not specifically address CPR or the outcomes of CPR.

Experimental subjects received the same handout, as well as another about CPR and its outcomes, and viewed a 10-minute videotape about advance directives (“Advance Directives: Guaranteeing Your Health Care Rights,” American Hospital Association, 1991). The CPR handout was developed by the authors on the basis of previous work.11,16,19 Subjects completed a preintervention questionnaire, received the control or educational intervention, saw their medical care provider, then completed a postintervention questionnaire. A follow-up questionnaire was mailed to all subjects 2 to 4 weeks following study entry.

Questionnaires were developed by the authors after review of existing instruments.5,13,16,19,20 The preintervention questionnaire assessed knowledge of advance directives, CPR, and outcomes of CPR; attitudes and preferences regarding advance directives and CPR; and previous discussions about advanced directives or CPR. The postintervention questionnaire consisted of the same questions as well as questions of whether CPR or advance directives were discussed during the clinic visit, whether they wished to discuss the issue with family, and whether the information was helpful. The follow-up questionnaire consisted of these questions as well as questions on whether CPR or advance directives were discussed with family and whether the patients had begun to prepare an advance directive. The majority of response options were dichotomous; a minority used an ordinal scale.

All handouts and questionnaires are available on request from the authors.

Analysis

Differences in the distribution of baseline characteristics between experimental and control groups were examined using logistic regression for dichotomous dependent variables and a proportional odds model for ordinal dependent variables.21 Similar regression techniques were used to compare effects of the experimental intervention with those of the control intervention based on the postintervention and follow-up questionnaires. Separate analyses were performed for each questionnaire.

Some subjects did not answer all questions on a particular questionnaire; an intention-to-treat approach was used in the analysis.

RESULTS

Characteristics

Of 334 patients contacted, 47 were unable to provide valid consent and were excluded. Refusals were most commonly due to “lack of time” (70 of 170) and “lack of interest” (57 of 170). All but 2 of 117 participating subjects were male. Age did not differ between the groups, mean = 74.1 years (range, 70–91 years).

Questionnaire Completion

Overall response rates for those agreeing to be in the study were 98.3% (115 of 117), 92.3% (108 of 117), and 76.9% (90 of 117) for the preintervention, postintervention, and follow-up questionnaires, respectively.

Preintervention Questionnaire

Responses of the two subject groups were similar for all but two questions in the preintervention questionnaire. Subjects in the experimental group tended to be less likely to report that they ever had, or that they wanted to have, a discussion about CPR or an advance directive with family.

Although more than two thirds said they knew what CPR was, no more than half of the subjects identified routine procedures in advanced cardiac life support. About one quarter of the subjects stated that they knew what an advance directive is, and one third of subjects at baseline correctly estimated their likelihood of being resuscitated and discharged home (Table 1). Approximately three quarters wanted CPR performed on themselves initially. Almost two thirds of subjects wanted to inform their physician of their preference for CPR. However, few subjects stated they had ever discussed CPR or advance directives with their physician.

Table 1.

Knowledge of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Advance Directives (ADs)

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Follow-Up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) |

| Intravenous fluid, % yes | 17.2 | 21.2 | 1.29 (0.36, 4.62) | 23.1* | 60.7* | 5.2 (1.57, 16.87)* | 25.9 | 42.3 | 2.10 (0.66, 6.68) |

| Tube in throat for breathing, % yes | 50.0 | 38.5 | 0.62 (0.24, 1.61) | 46.4* | 72.7* | 3.08 (1.06, 8.94)* | 33.3 | 51.5 | 2.12 (0.74, 6.08) |

| Breathing machine, % yes | 47.1 | 29.4 | 0.47 (0.17, 1.27) | 43.3* | 67.6* | 2.73 (0.99, 7.57)* | 37.9 | 51.6 | 1.74 (0.62, 4.88) |

| External shock, % yes | 54.6 | 38.9 | 0.53 (0.20, 1.38) | 56.7† | 78.1† | 2.73 (0.90, 8.26)† | 46.9† | 69.0† | 2.52 (0.88, 7.19)† |

| Know what CPR is, % yes | 69.8 | 74.4 | 1.26 (0.49, 3.24) | 75.9† | 93.8† | 4.77 (0.90, 25.23)† | 76.7 | 91.2 | 3.14 (0.73, 13.49) |

| Know what an AD is, % yes | 27.4 | 28.1 | 1.03 (0.44, 2.40) | 52.5* | 87.2* | 6.18 (2.15, 17.81)* | 40.0* | 72.3* | 3.92 (1.60, 9.64)* |

| Knowledge of CPR outcomes, % correct | 35.0 | 35.7 | 1.23 (0.44, 3.49) | 32.0* | 62.9* | 4.27 (1.57, 11.62)* | 37.5 | 37.5 | 1.21 (0.47, 3.15) |

p≤ .05.

p≤ .10.

Effects of Interventions

Postintervention Questionnaire

Following the intervention, experimental subjects tended to state more often that they knew what CPR is, and were more likely to state they knew what an advance directive is, than control subjects. Experimental subjects also more often identified correctly the procedural aspects of CPR, and were more likely to correctly estimate their likelihood of being resuscitated and discharged home (% correct 62.9 vs 32.0, p≤ .05) (Table 1).

Other than eliminating the preexisting difference in wanting to discuss CPR or advance directives with family, there were no postintervention differences between groups in their preferences for or activities regarding advance care planning. Although more than half of the subjects wanted to discuss advance care planning, few subjects in either group stated that they discussed CPR or advance directives with their physician on that day. The proportion preferring that CPR be performed on them remained approximately three quarters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reports of and Preferences for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Advance Directives (ADs)

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Follow-Up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) | Control | Expt. | Odds Ratio(95% CI) |

| Ever discussed CPR/AD with family, % yes | 35.3* | 20.7* | 0.48 (0.20, 1.13)* | ||||||

| Ever discussed CPR/AD with MD, % yes | 8.0 | 5.2 | 0.63 (0.13, 2.95) | ||||||

| Want to discuss CPR/AD with family, % yes | 64.0† | 43.9† | 0.44 (0.20, 0.96)† | 62.5 | 74.5 | 1.75 (0.70, 4.38) | 63.4 | 63.0 | 0.98 (0.41, 2.36) |

| Discussed CPR/AD with family, % yes | 27.5 | 40.0 | 1.76 (0.70, 4.39) | ||||||

| Wish to inform MD of preference, % yes | 70.6 | 62.5 | 0.69 (0.31, 1.56) | 54.0 | 68.9 | 1.88 (0.76, 4.65) | 57.9 | 59.1 | 1.05 (0.44, 2.54) |

| Discussed CPR/AD with MD today, % yes | 12.8 | 12.5 | 0.97 (0.26, 3.66) | ||||||

| Made or started to make an AD, % | 12.5 | 18.6 | 1.60 (0.48, 5.37) | ||||||

| Wish CPR performed, % yes | 77.4 | 78.0 | 1.04 (0.42, 2.52) | 80.5 | 75.6 | 0.75 (0.27, 2.10) | 71.4 | 66.0 | 0.78 (0.31, 1.91) |

p≤ .10.

p≤ .05.

Follow-Up Questionnaire.

In general, differences between the experimental and control groups lessened or disappeared in the follow-up questionnaire sent after 2 to 4 weeks. Subjects in the experimental group continued to state that they knew what an advance directive is more often than the control subjects (72.3% vs 40.0%, p≤ .05). At the follow-up questionnaire, one sixth of the combined subjects stated that they had started to prepare an advance directive.

DISCUSSION

We delivered a brief educational intervention consisting of two written handouts and a videotape about advance directives, CPR, and resuscitation outcomes to veteran subjects at least 70 years of age during the waiting time before a clinic appointment. Immediately following the intervention, knowledge of CPR improved both by self-assessment and by direct questioning, but this effect dissipated over the next few weeks. Only a small percentage of subjects discussed advance care planning with their physician or family, or started to prepare an advance directive.

Improvements in the estimation of resuscitation outcomes by subjects, such as those in our study, have been reported to be followed by a change in preferences for CPR.5,13,16 However, a fixed preference for CPR following education was also reported in veterans.15 Our study supports improvement in a group's knowledge about CPR outcomes, with the percentage of subjects wishing to undergo CPR becoming smaller with each successive questionnaire, although this change was not statistically significant. Our study may have been too small to detect a small difference in this preference.

The goal of many interventions has been to prompt the completion of advance directives, or at least discussions with family or physicians about the patient's wishes. An alternative goal of informed decision making, however, may have been achieved, at least in part, in our study. Even if educational interventions do not change the intention to develop an advance directive, or motivate its completion, those decisions that do take place can be more fully informed. The perceived adequacy of the experimental intervention without a change in intention or behavior relative to advance directives is consistent with previous work suggesting that patients desire information, although not necessarily to inform their decisions.22

Our intervention, which used “multiple methods” principles of adult learning,23 was effective in improving knowledge in the short term, supporting the notion that conveying information through more than one means may improve knowledge, even if it does not change behavior. The patient's self-reported comfort level in discussing CPR with their physician or family was high before and after the interventions, suggesting that other barriers (time, forgetfulness, procrastination, or lack of physician initiation) may more strongly influence the likelihood of discussing life-sustaining treatment with family or physician.

The small sample size may have led to important differences between groups being missed, so negative results should be interpreted cautiously. These results are also narrowly generalizable as the population was elderly male veterans in a university-affiliated VAMC. Although randomization between groups was unsuccessful based on measured baseline characteristics, these differences should only have made it more difficult for the experimental intervention to be successful given the direction of the differences.

In summary, we developed a convenient means of educating elderly male patients regarding CPR and advance directives that improved short-term knowledge, but did not stimulate advance care planning. Future efforts could be aimed at combining this multimedia educational intervention with other methods to increase advance care planning.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the outpatient nursing staff of the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davidson KW, Hackler C, Caradine DR, McCord RS. Physicians' attitudes on advance directives. JAMA. 1989;262:2415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical Ethics - A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co.; 1982. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greco PJ, Schulman KA, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Hansen-Flaschen J. The patient self-determination act and the future of advance directives. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:639–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-8-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annas GJ. The health care proxy and the living will. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(17):1210–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients' preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:545–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati RS, Bhan GL, Horan MA. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of old people. Lancet. 1983;2(8344):267–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy DJ, Murray AM, Robinson BE, Campion EW. Outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:199–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-3-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tresch DD, Thakur R, Hoffmann RG, Brooks HL. Comparison of outcome of resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in persons younger and older than 70 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:1120–2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longstreth WT, Cobb LA, Fahrenbruch CE, Copass MK. Does age affect outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation? JAMA. 1990;264(16):2109–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnin MJ, Pepe PE, Clark PS. Survival in the elderly after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(11):1645–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199311000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finucane TE. Attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation in nursing homes. Am J Med. 1993;95:121–2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90251-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenberg MS, Hallstrom A, Bergner L. Long-term survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(22):1340–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206033062206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller DL, Jahnigen DW, Gorbein MJ, Simbartl L. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: how useful? Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:578–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niemann JT. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(15):1075–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schonwetter RS, Teasdale TA, Taffet G, Robinson BE, Luchi RJ. Educating the elderly: cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions before and after intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:372–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonwetter RS, Walker RM, Kramer DR, Robinson BE. Resuscitation decision making in the elderly: the value of outcome data. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:295–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malloy TR, Wigton RS, Meeske J, Tape TG. The influence of treatment descriptions on advance medical directive decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1255–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elpern EH, Yellen SB, Burton LA. A preliminary investigation of opinions and behaviors regarding advance directives for medical care. Am J Crit Care. 1993;2:161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1285–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gates RA, Weaver MJ, Gates RH. Patient acceptance of an information sheet about cardiopulmonary resuscitation options. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:679–82. doi: 10.1007/BF02598286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCullagh P. Regression models for ordinal data. J Roy Stat Soc. 1980;42:109–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nease Rf, Jr, Brooks WB. Patient desire for information and decision making in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(11):593–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02602742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]