Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe the etiologies of syncope in hospitalized patients and determine the factors that influence survival after discharge.

DESIGN

Observational retrospective cohort.

SETTING

Department of Veterans Affairs hospital, group-model HMO, and Medicare population in Oregon.

PATIENTS

Hospitalized individuals (n = 1,516; mean age ± SD, 73.0 ± 13.4 years) with an admission or discharge diagnosis of syncope (ICD-9-CM 780.2) during 1992, 1993, or 1994.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

During a median hospital stay of 3 days, most individuals received an electrocardiogram (97%) and prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring (90%), but few underwent electrophysiology testing (2%) or tilt-table testing (0.7%). The treating clinicians identified cardiovascular causes of syncope in 19% of individuals and noncardiovascular causes in 40%. The remaining 42% of individuals were discharged with unexplained syncope. Complete heart block (2.4%) and ventricular tachycardia (2.3%) were rarely identified as the cause of syncope. Pacemakers were implanted in 28% of the patients with cardiovascular syncope and 0.4% of the others. No patient received an implantable defibrillator. All-cause mortality ± SE was 1.1%± 0.3% during the admission, 13%± 1% at 1 year, and 41%± 2% at 4 years. The adjusted relative risk (RR) of dying for individuals with cardiovascular syncope (RR 1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92, 1.50) did not differ from that for unexplained syncope (RR 1.0) and noncardiovascular syncope (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.77, 1.16).

CONCLUSIONS

Among these elderly patients hospitalized with syncope, noncardiovascular causes were twice as common as cardiovascular causes. Because survival was not related to the cause of syncope, clinicians cannot be reassured that hospitalized elderly patients with noncardiovascular and unexplained syncope will have excellent outcomes.

Keywords: syncope, prognosis, mortality

Many individuals with syncope are admitted to the hospital for diagnostic evaluation; in fact, syncope accounts for 1% to 6% of all hospital admissions.1 Population-based studies from the 1980s underscored the importance of diagnosing the cause of syncope.2–6 Individuals with syncope of cardiovascular origin had a higher 1-year mortality (18%–33%) than individuals with noncardiovascular or unexplained syncope (6%–12%), 2–6 and this increased risk continued for 5 years.7 However, determining the etiology of a syncopal event was a diagnostic challenge that was unsuccessful in up to 47% of cases.2–6

This discordance between a physician's ability to establish a diagnosis for a syncopal event and the prognostic importance of doing so has inspired much research on evaluating syncopal events. This literature on syncope, often involving single-center referral populations and a single diagnostic test, 8–13 was summarized by a recent consensus conference.14,15 However, the use of these newer diagnostic testing modalities and the ability to identify etiologies of syncope, have not been described in an unselected population. Furthermore, the prognostic significance of cardiovascular syncope has been questioned in patients with heart disease and in the elderly, 9,16 but has not been reevaluated in more broadly defined populations during the current era of diagnostic testing.

The goals of this study were to characterize the epidemiology of individuals hospitalized with syncope in a broad range of health care delivery settings. We wanted to describe the diagnostic testing and the results of diagnostic evaluations, and to determine if the etiology of syncope continued to predict mortality in an unselected community-based population.

METHODS

Study Design and Source of Patients

This study used an observational cohort design. To minimize referral and institutional bias, we selected populations served by three diverse health care systems in Oregon: a tertiary-care VA hospital, a group-model HMO, and Medicare. The Medicare population was drawn from all hospitals in Oregon. We reviewed the hospitalization databases of these organizations from January 1, 1992, through December 31, 1994, identifying patients with ICD-9-CM code 780.2 (syncope and collapse) as an admission diagnosis or as any one of the discharge diagnoses. This method of retrospectively identifying individuals with syncope on the basis of coded diagnoses is similar to methods used in several previous studies.3,5,17,18 The first admission for a patient during the study time frame was identified for review; subsequent admissions were not included. There were 324 patients identified at the VA (0.98% of all admissions), 818 at the HMO (0.92%), and 5,314 (1.70%) from the Medicare population. After excluding Medicare patients admitted to the group-model HMO's hospitals, a sample of the remaining Medicare charts was selected at random (n = 554).

Study Population

Medical records on the 1,696 individuals were reviewed by one individual (WSG). The inclusion criterion was a documented syncopal event that occurred prior to hospital admission. We defined syncope as a transient loss of consciousness that resolved spontaneously. Exclusion criteria were cardiac arrest or a persistently altered level of consciousness. For individuals transferred to another hospital during their admission, both hospitals' records were reviewed and considered as one hospitalization. After initial review, 180 individuals (11%) were excluded, primarily because they had not experienced a true syncopal event (n = 107). Other reasons for exclusion were syncope occurring after admission (n = 40), miscoding (n = 22), and unavailable charts (n = 11). Overall, 1,516 patients with syncope were available for analysis.

The ICD-9-CM code 780.2 (syncope and collapse) was listed as the admission diagnosis for 67% of the patients with documented syncope. Among the 501 patients without an admission diagnosis of syncope, 32% had syncope as the principal discharge diagnosis, while 68% had syncope as a secondary discharge diagnosis. Our case ascertainment strategy could not identify individuals with syncope who had an alternative admission diagnosis and also did not have syncope coded in one of the 10 discharge diagnosis positions.

Chart Review Data Collection

We reviewed each admission in detail and recorded comorbidities included in the Charlson index.19 For other cardiac conditions, we used standard definitions. Medical problems identified during the admission were recorded separately from preexisting conditions. Diagnostic test use was recorded; however, results were documented only for left ventricular systolic function measurements. Interventions such as pacemaker placement or cardioversion were also recorded. We used physicians', nurses', and social workers' notes to determine where patients lived before admission and at discharge.

We defined the etiology of the syncopal event as the one determined by the treating physician, and later categorized diagnoses as cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, or unexplained according to Kapoor's groupings.2 Because determining the etiology of syncope relies on history and physical examination findings 2,14 which may not have been recorded in the chart, we felt that overruling the clinicians' diagnoses would be inaccurate. In addition, using the diagnoses clinicians establish during actual practice provides results that may be more generalizable than those obtained using rigid abstraction protocols. While retrospectively analyzing the charts of 100 patients with syncope, Eagle and Black 5 found that independent reviewers using strict criteria agreed with the attending physician's impression in all cases.

In the HMO and the VA, outpatient records and recurrent admissions within 90 days after discharge were reviewed to determine diagnostic evaluations occurring as an outpatient. When new etiologies for syncope were established, they were recorded separately from initial diagnostic impressions. Clinic visits were not available for Medicare patients, but recurrent admissions were reviewed in similar fashion. As the amount of testing after discharge was clearly less than during the hospitalization, we have used inpatient results in our analyses to combine data from the different health care systems, except where noted.

A second person blindly re-reviewed a random selection constituting 5% of the 1,516 admissions. Weighted κ scores between the two reviewers were 0.71 for comorbidities, 0.79 for tests and therapies, and 0.91 for etiology of syncope. A κ score above 0.75 indicates excellent reliability.20

Deaths

The primary long-term outcome was death from any cause. Names and social security numbers were submitted to the National Death Index to match with deaths through December 31, 1996. This index is 99.9% specific and 97% sensitive when the social security number is available.21 Partial matches were all explicitly reviewed. Only 3 of 444 individuals identified as deceased by chart review (death certificate, autopsy, or Medicare files) were not identified by the index. Individuals not identified as deceased are assumed to have been alive on December 31, 1996, and their survival times are censored on that date. For comparison, we calculated expected 4-year mortality rates for the general U.S. population using 1995 vital statistics, and adjusting for age and sex.22

Statistical Analysis

Statistical testing was performed using SPSS version 7.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). Continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test. The χ2test was used to compare dichotomous variables.20 Survival curves were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier 23 and compared using the log-rank test. All tests of hypotheses were considered significant when two-sided probability values were p < .05.

Cox proportional hazards analysis 24 was used to evaluate the influence of syncope etiology on survival after hospital discharge, after adjusting for age, comorbidity, and other prognostic factors. Becaus e we suspected that age and comorbidity were not linearly related to survival, multiple expressions of the variables were tested using likelihood ratios to determine the best fit. Age was entered into the model as a polynomial through the third power. Comorbidities were combined into the Charlson index and grouped into four categories (0, 1–2, 3–4, and 5 or more) for use as an ordinal variable. Other predetermined variables were tested in univariate fashion against mortality using Kaplan-Meier survival and the log-rank test. Variables reaching significance at p≤ .20 were included in the second block using forward stepwise regression, requiring p≤ .05 for entry.

The variables in the final model were age, age-squared, age-cubed, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, congestive heart failure, aortic stenosis, number of medical problems addressed during the admission, active malignancy during the admission, dehydration during the admission, distance from the hospital (more than or less than 50 miles), health care system (Medicare, VA, or HMO), left ventricular systolic function (unknown, normal to mildly reduced, or moderate to severely reduced), living arrangements at discharge (independent, assisted care, or nursing facility), and the etiology of the syncopal event (unexplained, noncardiovascular, or cardiovascular.) We tested multiple variables for interactions with age, sex, and health care system. The only interaction that reached significance was between age (in its polynomial form) and comorbidity. A formal test of homogeneity of the three systems for the main effects of etiology of syncope on survival supported combining the data sources for the main analyses.

RESULTS

Demographics and Comorbidity

From the specified 3-year period, we reviewed the admissions of 744 individuals with syncope at the HMO, 487 in the Medicare population, and 285 at the VA (Table 1) The mean age (±SD) was 73.0 (±13.4) years. Almost two thirds lived in the Portland metropolitan area, and only 6.5% were admitted to rural hospitals. Most patients were living at home before admission and were admitted through the emergency department. Preexisting cardiac disease was common in the population, and hypertension was described in almost half of the patients. The reviewed admission was the first episode of syncope for 1,191 (79%) of the 1,516 patients. The median length of stay was 3 days.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals Admitted to the Hospital with Syncope

| Characteristic | Value *(n = 1,516) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (25th, 75th percentiles) | 75 (67,82) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,455 (96.0) |

| Male sex | 847 (55.9) |

| Living status prior to admission | |

| Independent | 1,366 (90.1) |

| Assisted care | 129 (8.5) |

| Nursing home | 20 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) |

| Admission source | |

| Emergency dept. | 1,282 (84.6) |

| Clinic visit | 123 (8.1) |

| Hospital transfer | 58 (3.8) |

| Elective | 30 (2.0) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (1.5) |

| Cardiac disease prior to admission | |

| Coronary artery disease | 518 (34.2) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 250 (16.5) |

| Congestive heart failure | 258 (17.0) |

| Aortic stenosis | 77 (5.1) |

| Dysrhythmias prior to admission | |

| Complete heart block | 21 (1.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 277 (18.3) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 71 (4.7) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 40 (2.6) |

| Pacemaker | 57 (3.8) |

| Defibrillator | 7 (0.5) |

| Other comorbid diseases prior to admission | |

| Hypertension | 688 (45.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 110 (7.3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 330 (21.8) |

| Dementia | 146 (9.6) |

| Diabetes | 252 (16.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | 490 (32.3) |

| 1 or 2 | 656 (43.3) |

| 3 or 4 | 273 (18.0) |

| 5 or more | 97 (6.4) |

All values are n(%) unless otherwise specified.

Etiologies of Syncopal Events

The treating clinicians assigned cardiovascular causes of syncope during the admission in 19% of patients. The most common cardiovascular etiologies (Table 2) were arrhythmias, but complete heart block and ventricular tachycardia were each identified as the etiology of syncope for only 2% of patients. Obstructive cardiac causes of syncope were infrequently identified: there were 14 individuals with aortic stenosis, 10 with pulmonary emboli, and no patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Table 2.

Etiology of the Syncopal Event

| Etiology | n(%)(n= 1,516) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 284 (18.7) |

| Bradycardia, unspecified | 52 (3.4) |

| Complete heart block | 36 (2.4) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 35 (2.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 34 (2.2) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 25 (1.6) |

| Sick sinus syndrome | 23 (1.5) |

| Myocardial ischemia | 16 (1.1) |

| Aortic stenosis | 14 (0.9) |

| Pulmonary embolus | 10 (0.7) |

| Mobitz 2 heart block | 9 (0.6) |

| Pacemaker dysfunction | 3 (0.2) |

| Other cardiovascular * | 27 (1.8) |

| Noncardiovascular | 602 (39.7) |

| Vasovagal | 175 (11.5) |

| Orthostasis or dehydration | 166 (10.9) |

| Drug induced | 55 (3.6) |

| Bleeding or anemia | 33 (2.2) |

| Seizures | 29 (1.9) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 18 (1.2) |

| Micturation or tussive | 18 (1.2) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 13 (0.9) |

| Psychiatric | 9 (0.6) |

| Other noncardiovascular † | 86 (5.7) |

| Unexplained | 630 (41.6) |

Includes unspecified arrhythmias, carotid sinus syncope, ruptured aorta, and miscellaneous.

Includes infections, vertigo, hypoglycemia, subclavian steal, and miscellaneous.

Noncardiovascular causes of syncope were assigned twice as often as cardiovascular etiologies, accounting for 40% of all patients. The most common noncardiovascular causes assigned by physicians were vasovagal syncope, orthostasis or dehydration, and medication-induced syncope. Neurologic etiologies accounted for 4% of patients.

The remaining 42% of individuals were discharged without a diagnosis for their syncopal event. The ages (p = .16), ethnicity (p = .09), gender (p = .21), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (p = .22), and frequency of previous syncope (p = .16) of the patients were distributed similarly among the groups. As expected, individuals with cardiovascular syncope had more preexisting cardiac disease, including atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease (p < .01), than the other groups.

Inpatient Diagnostic Testing

Because we did not know if diagnostic tests or interventions were performed before or after the establishment of the etiology of syncope, we separated the population into three etiologic groups for all analyses.

Twelve-lead electrocardiography (ECG) and telemetry monitoring were performed frequently in all three groups; however, there were more individuals with noncardiovascular syncope who did not undergo telemetry monitoring (Table 3)Individuals with cardiovascular syncope were more likely to undergo echocardiography, cardiac catheterizations, and electrophysiology studies, but very few individuals, regardless of the etiology of syncope, underwent signal-averaged ECG, tilt-table testing, and thallium studies. Individuals with unexplained syncope had more neurologic testing, including computed tomographic scans of the head and electroencephalograms.

Table 3.

Tests Performed During the Syncope Admission

| Test | CardiovascularSyncope, %(n= 284) | 95% CI forDifferenceBetweenCV and UN * | NoncardiovascularSyncope, %(n= 602) | 95% CI forDifferenceBetweenNCV and UN † | UnexplainedSyncope, %(n= 630) | p‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard cardiac tests | ||||||

| 12-Lead electrocardiogram | 99.6 | (0.0, 3.4) | 95.5 | (−4.4, −0.4) | 97.9 | .001 |

| Telemetry monitoring | 98.6 | (3.5, 10.1) | 82.1 | (−13.7, −6.3) | 92.1 | <.001 |

| Rule-out myocardial infarction § | 46.1 | (−6.1, 7.9) | 36.4 | (−14.3, −3.3) | 45.2 | .002 |

| Exercise test | 5.3 | (−4.6, 2.2) | 3.7 | (−5.3, −0.3) | 6.5 | .08 |

| Holter monitoring | 1.8 | (−5.1, 0.1) | 1.5 | (−4.7, −0.9) | 4.3 | .006 |

| Advanced cardiac tests | ||||||

| Echocardiogram | 27.8 | (4.5, 15.9) | 10.5 | (−11.0, −3.2) | 17.6 | <.001 |

| Cardiac catheterization | 12.7 | (6.4, 13.0) | 1.5 | (−3.2, 0.2) | 3.0 | <.001 |

| Electrophysiology study | 4.9 | (0.7, 5.3) | 0.5 | (−2.6, −0.2) | 1.9 | <.001 |

| Stress thallium | 3.2 | (−0.4, 3.6) | 2.0 | (−1.1, 1.9) | 1.6 | .29 |

| Signal-averaged electrocardiogram | 1.8 | (−0.8, 2.4) | 0.3 | (−1.6, 0.2) | 1.0 | .09 |

| Tilt table | 1.4 | (−0.3, 2.1) | 0.7 | (−0.7, 1.1) | 0.5 | .30 |

| MUGA scan ∥ | 1.4 | (−1.1, 1.9) | 0.5 | (−1.5, 0.5) | 1.0 | .37 |

| Neurologic tests | ||||||

| Computed tomography, head | 11.3 | (−17.6, −6.4) | 20.1 | (−7.8, 1.4) | 23.3 | <.001 |

| Carotid ultrasound | 7.4 | (−8.2, 0.2) | 8.8 | (−6.0, 0.8) | 11.4 | .11 |

| Electroencephalogram | 4.6 | (−16, −6.8) | 8.8 | (−10.9, −3.5) | 16.0 | <.001 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging, brain | 1.8 | (−4.3, 0.5) | 3.8 | (−2.0, 2.2) | 3.7 | .25 |

| Lumbar puncture | 0.4 | (−2.7, 0.3) | 1.0 | (−1.9, 0.7) | 1.6 | .24 |

Confidence intervals (95%) for the absolute percentage difference between cardiovascular syncope and unexplained syncope.

Confidence intervals (95%) for the absolute percentage difference between noncardiovascular syncope and unexplained syncope.

p Values are derived from overall χ2for differences between the three groups.

Defined as the use of telemetry and the measurement of at least two creatine phosphokinase levels in the first 24 hours of admission.

MUGA indicates multiple gated acquisition radionuclide fraction.

Inpatient Interventions

As expected, most major interventions were provided to individuals with cardiovascular syncope (Table 4)Permanent pacemakers were implanted in nearly one third of these individuals, compared with none of the patients with noncardiovascular syncope and five patients with unexplained syncope (p < .001). Other major interventions were infrequently performed, but again primarily in individuals with cardiovascular syncope. No patient received an implantable defibrillator.

Table 4.

Interventions During the Syncope Admission *

| Intervention | CardiovascularSyncope(n= 284) | 95% CI forDifferenceBetweenCV and UN † | NoncardiovascularSyncope(n= 602) | 95% CI forDifferenceBetweenNCV and UN ‡ | UnexplainedSyncope(n= 630) | p§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major cardiac therapies | ||||||

| Pacemaker placement | 28.2 | (23.3, 31.5) | 0.0 | (−1.5, −0.1) | 0.8 | <.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 2.8 | (0.8, 3.8) | 0.0 | (−1.1, 0.1) | 0.5 | <.001 |

| Valve replacement | 2.5 | (1.3, 3.7) | 0.2 | NA | 0.0 | <.001 |

| Angioplasty | 0.4 | (−0.5, 0.9) | 0.3 | (−0.5, 0.7) | 0.2 | .80 |

| Defibrillator | 0.0 | NA | 0.0 | NA | 0.0 | NA |

| Other therapies | ||||||

| Cardioversion | 3.5 | (2.0, 5.0) | 0.0 | NA | 0.0 | <.001 |

| Temporary pacemaker | 3.5 | (1.6, 4.8) | 0.3 | (−0.6, 0.6) | 0.3 | <.001 |

| New type 1 antiarrhythmic | 10.2 | (7.1, 12.3) | 0.5 | (−0.8, 0.8) | 0.5 | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular medications ∥ increased | 10.6 | (−0.3, 7.3) | 6.1 | (−3.8, 1.8) | 7.1 | .06 |

| Cardiovascular medications reduced | 22.9 | (9.5, 18.9) | 15.8 | (3.4, 10.8) | 8.7 | <.001 |

| Intravenous fluid rehydration | 2.5 | (−4.2, 1.0) | 22.9 | (15, 22.6) | 4.1 | <.001 |

| Fludrocortisone | 0.4 | (−0.5, 0.9) | 2.8 | (1.3, 3.9) | 0.2 | <.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 2.1 | (−2.5, 1.7) | 8.1 | (3.1, 8.1) | 2.5 | <.001 |

| New seizure medication | 0.0 | (−1.8, 0.2) | 3.0 | (0.7, 3.7) | 0.8 | <.001 |

| No specific therapy | 12.7 | (−70.5, −56.7) | 64.8 | (−16.6, −6.4) | 76.3 | <.001 |

All values are percent (95% confidence intervals). Percentages do not add to 100 as some individuals received multiple interventions. NA indicates not applicable.

Confidence intervals (95%) for the absolute percentage difference between cardiovascular syncope and unexplained syncope.

Confidence intervals (95%) for the absolute percentage difference between noncardiovascular syncope and unexplained syncope.

p Values are derived from overall χ2for differences between the three groups.

Beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, diuretics, digoxin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or hydralazine.

Less-invasive interventions were provided in all groups. Type 1 antiarrhythmic agents were given to 10.2% of patients with cardiovascular syncope, of whom 3.1% received type 1c agents. Few patients required cardioversion or temporary pacemaker placement. Cardiovascular medications were frequently changed, especially in the group with cardiovascular syncope. No specific therapy was provided for 64.8% of the noncardiovascular syncope group and 76.3% of the unexplained syncope group, compared with only 12.7% of individuals with cardiovascular syncope (p < .001).

Evaluation After Discharge

We reviewed the outpatient records for 458 patients discharged with unexplained syncope at the HMO and the VA (no outpatient records were available for the Medicare population). During the 90 days after discharge, new diagnostic tests were performed in few patients: 31 Holter monitors, 43 event monitors, 20 exercise stress tests, 25 echocardiograms, 4 thallium stress tests, 8 cardiac catheterizations, 1 electrophysiology study, and no tilt-table tests or signal-averaged ECGs. Seven new etiologies for the original syncopal event were established: five individuals with supraventricular rhythms, one with aortic stenosis, and one with complete heart block. These new diagnoses accounted for 1.5% of the patients with unexplained syncope in the HMO and the VA. There were nine permanent pacemakers implanted, but no valve surgery or defibrillator implantation.

In the Medicare population, inpatient records from the 90 days after discharge suggested similarly low rates of testing in patients with initially unexplained syncope (n = 172). Five new diagnoses for syncope were established (2.9%): one individual with ventricular tachycardia, one with complete heart block, and one each with orthostasis, bleeding, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency. One individual received a permanent pacemaker, and none underwent valve replacement surgery or received an implantable defibrillator.

In summary, 15% of patients discharged with unexplained syncope underwent ambulatory cardiac monitoring in the 3 months after discharge. However, other tests and interventions were rarely performed after discharge, and 98.5% of the patients did not have a cause of syncope established. We used the cause of syncope at the time of hospital discharge to combine data from all three systems for our analyses.

Survival after Discharge

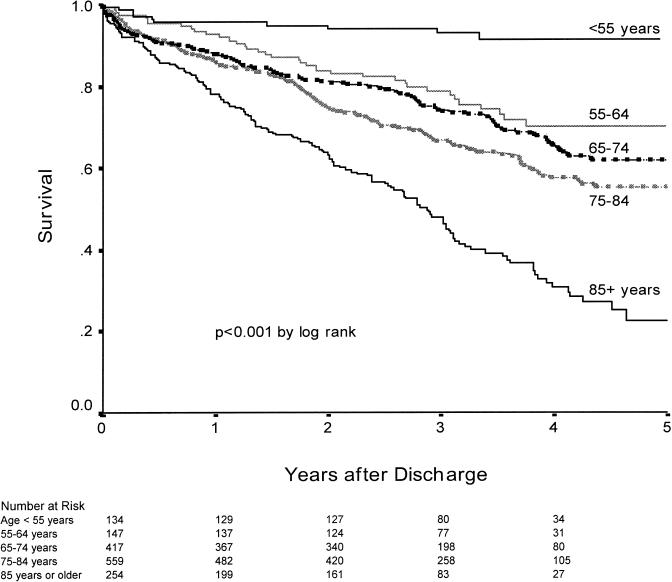

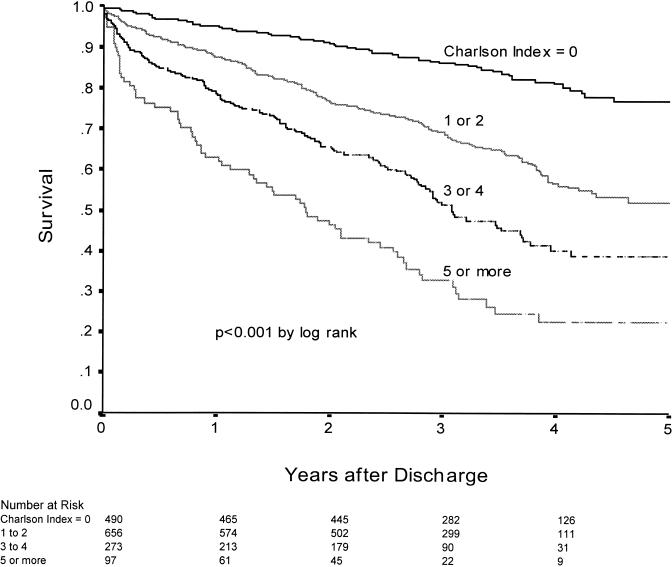

The median follow-up time after hospital discharge was 2.8 years with a maximum of 5.0 years. Mortality (±SE) for the study population was 1.1%± 0.3% during the admission, 13.4%± 0.9% at 1 year, and 40.6%± 1.6% at 4 years. The expected 4-year mortality for this population 19(adjusted for age and sex) was 22.6%. Thus, the cohort of patients with syncope had a 79% higher risk of dying than would be expected over 4 years. The risk of dying was strongly related to age (Fig. 1) and comorbidity (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Influence of age on survival after syncope admission (n = 1,516). Survival after an admission for syncope is profoundly affected by age.

FIGURE 2.

Influence of Charlson Comorbidity Index on survival after syncope admission (n = 1,516). A marked difference in survival is seen for patients with higher Charlson indices. These differences continue for the entire period of follow-up.

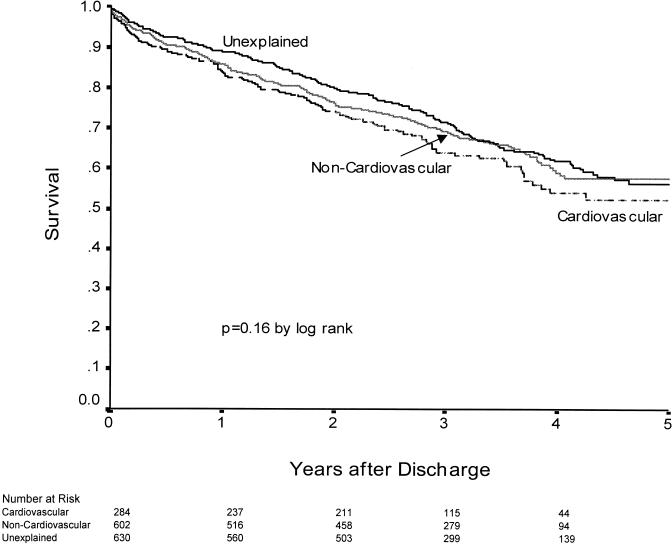

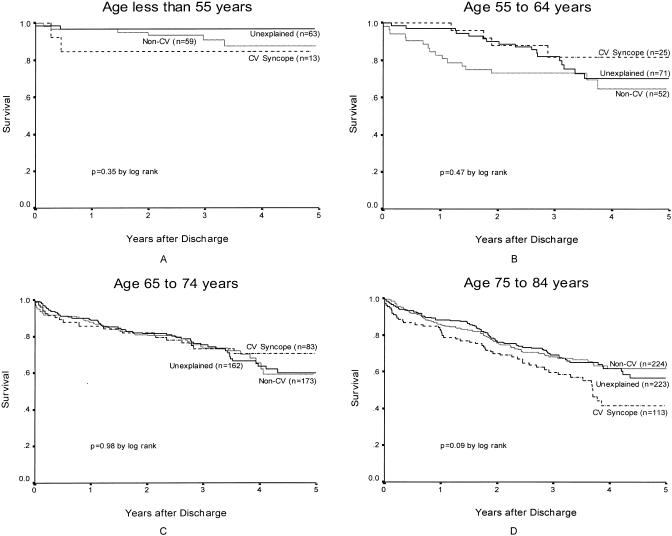

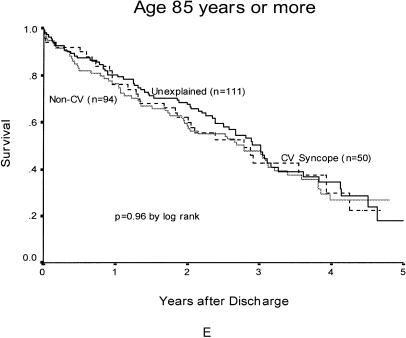

At 4 years, the mortality for cardiovascular syncope was 46.3%± 3.8%; for noncardiovascular syncope, 40.8%± 2.6%; and for unexplained syncope, 38.2%± 2.3%(Fig. 3). Although there was an 8.1% range between groups in estimated mortality at 4 years, the survival curves (p = .16 by log rank) did not differ significantly. Stratifying by age group did not change the relation between the different etiologies of syncope (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

Unadjusted survival after syncope: influence of the etiology of syncope (n = 1,516). Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves show no differences in survival between the causes of syncope.

Figure 4.

Age-stratified survival among patients with different etiologies of syncope. (A) Individuals younger than 55 years; (B) individuals between 55 and 64 years of age; (C) individuals between 65 and 74 years of age; (D) individuals between 75 and 84 years of age; and (E) individuals 85 years of age or older. Survival in each age stratum does not differ among individuals with different etiologies of syncope; p values from log-rank tests are adjusted for secondary comparisons. Cardiovascular syncope, dotted line; unexplained syncope, solid black line; noncardiovascular syncope, gray line. CV denotes cardiovascular.

To adjust for baseline differences between the groups, we used a multivariate model of survival. After adjusting for age, gender, comorbidity, congestive heart failure, aortic stenosis, left ventricular systolic function, active medical problems, discharge to nursing home or assisted care, health care system, and distance from the hospital, the etiology of syncope was not related to mortality (p = .23). Compared with unexplained syncope (reference category relative risk [RR] 1.0), the relative risk of dying after discharge with cardiovascular syncope was 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92, 1.50), and was 0.94 (95% CI 0.77, 1.16) with noncardiovascular syncope.

Limiting the multivariate analysis to individuals aged 65 years or older did not change these findings. Changing the reference category for cardiovascular syncope to the group of unexplained and noncardiovascular syncope provided similar findings (RR 1.21; 95% CI 0.96, 1.52). An analysis of individuals at the VA and the HMO, which included diagnoses established as an outpatient, did not change the results. Antiarrhythmic drug use, pacemaker implantation, coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, and previous syncope were not predictors of survival in the multivariate model (data not shown.)

Systematic Differences in Inpatient Management

The VA population was younger (mean, 66 years) than the HMO or Medicare populations (mean, 72 and 79 years), had more preexisting heart disease, and underwent slightly more testing. The HMO and Medicare populations had very similar demographics and testing, but the HMO population had slightly less comorbid illness. The rates of cardiovascular syncope were 16% at the HMO, 18% at the VA, and 23% in the Medicare population; they included, respectively, 2.8%, 2.1%, and 1.8% with complete heart block and 1.5%, 2.7%, and 3.9% with ventricular tachycardia. These clinically small differences in diagnoses are due to differences in age and preexisting heart disease. All systems provided virtually identical rates of intervention.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of more than 1,500 elderly hospitalized patients with syncope, the inpatient evaluation of syncope was relatively parsimonious; the population identified as having noncardiovascular syncope was twice as large as that with cardiovascular syncope; and the etiology of the syncopal event as determined by the treating physician did not have prognostic significance, while age and comorbidity had a profound impact on survival.

Among individuals with unexplained syncope, most had a 12-lead ECG (98%) and prolonged ECG monitoring (93%), yet electrophysiology testing was rarely performed (2%), and newer tests suggested for evaluating syncope—signal–averaged ECG and tilt-table testing—were virtually never performed (<1%), perhaps reflecting the inpatient nature of this study. Despite this relative paucity of cardiac tests, many individuals underwent electroencephalography (16%), carotid ultrasound (11%), and computed tomography of the head (23%), implying that clinicians were focusing on neurologic etiologies more than cardiac causes, despite descriptions of low yield from neurologic testing for syncope.2,5

Most clinicians provided some therapeutic intervention or medication change for individuals with cardiovascular syncope. However, no specific therapy was provided for many of the others, suggesting that clinicians were wary of treating syncope without an identified cause. No patients received implantable defibrillators, possibly because most defibrillators in use during the years reviewed in this study required thoracotomy for implantation.

Some previous data suggest that hospitalized patients and the elderly have a higher frequency of cardiovascular syncope, 2–4 but conflicting reports indicate a high incidence of noncardiovascular syncope in the elderly.16,25 Our cohort of elderly, hospitalized patients was twice as likely to have noncardiovascular syncope, and interestingly, the prevalence of specific etiologies in our study closely parallels data pooled from diverse populations.14

The concerns about sudden death after syncope are often tied to cardiac dysrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia.2 The incidence of ventricular tachycardia as the etiology of syncope was less than one might expect. Previous studies have suggested that 21% of patients with heart disease (about half of our population) who have syncope will have inducible ventricular tachycardia during electrophysiology testing, 15 while we report a 2.3% incidence of ventricular tachycardia overall. One may speculate that more ventricular tachycardia would have been identified if diagnostic evaluations were more extensive, but the difference may result from differences in the populations. We included all individuals hospitalized with syncope, while patients referred for electrophysiology testing reflect a more select, younger population.

Individuals in our study with cardiovascular syncope had the same long-term prognosis as individuals with noncardiovascular and unexplained syncope in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The strength of this conclusion is supported by a post hoc analysis, 26 which showed that our study had a power of at least 83% to detect a 30% increased hazard of dying for patients with cardiovascular syncope as compared with other etiologies.

One reason why our results might differ from previous data is that we relied on clinicians to establish the etiology of syncope, reviewing their findings retrospectively. Because establishing the etiology of syncope relies on the history and physical exam, 2,14 we felt that overruling and “second guessing” the treating physician would introduce inaccuracies. As mentioned, our treating clinician diagnoses resulted in nearly identical frequencies for specific etiologies of syncope as previous pooled data, 14 and it is unlikely that misclassification accounts for our findings.

Another possibility is that clinicians effectively treated cardiovascular syncope such that the mortality was reduced to the rates for noncardiovascular or unexplained syncope. Although most individuals with cardiovascular syncope received interventions, no interventions have been shown to prolong survival for patients with syncope. In addition, the predominant interventions, pacemaker implantation and antiarrhythmic drug use, did not affect survival.

A third possibility is that our hospitalized, elderly patients are a different population than the previously studied individuals with syncope. The mean age in our population was 73 years, while most population-based studies have described mean ages between 41 and 67 years.2–6,17,18 The age differential may simply reflect our entirely hospitalized population, as individuals discharged from an emergency department tend to be younger than those who are admitted, 4 but it may also reflect a change in the criteria for hospital admission over time. Although some suggest that syncope in the elderly is a different syndrome, 16,25 our stratified analyses showed no survival differences between etiologies of syncope for any age group.

Converse to the negligible impact of syncopal etiology on survival, the effects of age and comorbid illness were profound. Individuals under the age of 55 years had generally excellent outcomes, with 91% survival at 4 years. On the other hand, individuals aged 85 years or older had dismal outcomes, with 78% survival at 1 year and 31% survival at 4 years. Similarly, individuals with no comorbid illness had survival of 81% at 4 years, compared with 23% survival for individuals with extensive comorbidity. Presumably, low-risk patients were not admitted to the hospital, 2,4,6 so these survival figures cannot be applied to all individuals with syncope. However, they may provide a benchmark for estimating risk and planning therapy for individuals admitted to the hospital after syncopal events.

The finding that the syncope etiology does not confer prognostic significance supports a case-control study in which syncope was not a risk factor for mortality, after controlling for cardiac disease.27 As we only evaluated patients with syncope, we cannot comment directly; however, the 4-year mortality (41%) of our population was 79% greater than expected in the U.S. population. It is unclear whether this increased mortality results from associated comorbid conditions or relates specifically to syncope.

The population of individuals that this study represents is not the entire universe of patients with syncope. Obviously, many individuals will suffer syncope and never see a clinician, while others will see a physician and not be admitted. The most important limitation of our study is that some individuals who have syncope and are admitted for their syncope may be admitted under a presumed or verified etiology and not have syncope listed in the admission or discharge diagnoses. Such individuals would not be included in our study. If these individuals were more likely to have a particular etiology for their syncope, such as complete heart block or other cardiac causes, our estimates of the frequencies for particular etiologies, for diagnostic tests performed, and for interventions performed may be in error. However, we believe that this study captures a critically important population of individuals with syncope. Our population includes individuals with transient spells of loss of consciousness who were admitted for diagnostic testing, therapeutic intervention, or perhaps only for safety monitoring. These are the individuals that raise concern among clinicians as to the best way to proceed, and for whom the results are most generalizable.

Another important limitation of this study is that our data sources, although representative, are not a true random sample of the full spectrum of health care delivery. Thus, our estimates of frequency for comorbidity, diagnostic testing, etiology of syncope, and therapeutic intervention may differ from circumstances with different health care delivery system representation. However, because case ascertainment and data collection were performed identically for each system, and our unit of analysis was each individual, not the health care system, we feel that the combination of these different data sources does not undermine our main findings. Involvement of medical residents may affect the process of care, but is unlikely to alter the etiology of syncope or the long-term outcomes.

This cohort of individuals admitted to the hospital with syncope was elderly and had significant comorbidity, yet extensive evaluations were uncommon. Noncardiovascular etiologies were identified twice as often as cardiovascular etiologies, but 42% of patients were discharged without a diagnosis of syncope established. Four-year survival was 59%, and was not affected by the etiology of the syncopal event.

From this retrospective assessment, it is not possible to define the appropriate evaluation and treatment for patients with syncope. However, as mortality was so strongly related to comorbidity and age, rather than the etiology of syncope, aggressively managing underlying diseases and optimizing the use of appropriate therapies could potentially improve survival. Clinicians caring for individuals with noncardiovascular and unexplained syncope cannot be reassured that their patients will have excellent outcomes. Future research on improving survival for patients hospitalized with syncope should focus not only on diagnosis and treatment of the syncopal event, but on the whole individual.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Getchell received partial salary support from a grant (T32 HS00069) by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, National Research Service Award Institutional Grant Program. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. John Grover, Dr. Ruth Medak, Dr. Xiaoyan Huang, and Sara Denning-Bolle to the study design and data collection. We also thank the Oregon Medical Professional Review Organization, Kaiser Permanente Northwest Health Maintenance Organization, and the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center for their participation in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapoor WN. Evaluation and management of the patient with syncope. JAMA. 1992;268:2553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson JR, Levey GS. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:197–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307283090401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverstein MD, Singer DE, Mulley AG, Thibault GE, Barnett GO. Patients with syncope admitted to medical intensive care units. JAMA. 1982;248:1185–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day SC, Cook EF, Funkenstein H, Goldman L. Evaluation and outcome of emergency room patients with transient loss of consciousness. Am J Med. 1982;73:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90913-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle KA, Black HR. The impact of diagnostic tests in evaluating patients with syncope. Yale J Biol Med. 1983;56:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin GJ, Adams SL, Martin HG, Mathews J, Zull D, Scanlon PJ. Prospective evaluation of syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:499–504. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor WN. Evaluation and outcomes of patients with syncope. Medicine. 1990;69:160–75. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinberg JS, Prystowsky E, Freedman RA, et al. Use of the signal-averaged electrocardiogram for predicting inducible ventricular tachycardia in patients with unexplained syncope: relation to clinical variables in a multivariate analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middlekauff HR, Stevenson WG, Saxon LA. Prognosis after syncope: impact of left ventricular function. Am Heart J. 1993;125:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90064-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapoor WN, Smith MA, Miller NL. Upright tilt testing in evaluating syncope: a comprehensive literature review. Am J Med. 1994;97:78–88. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty JU, Pembrook RD, Grogan EW, et al. Electrophysiologic evaluation and follow-up characteristics of patients with recurrent unexplained syncope and presyncope. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:703–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krol RB, Morady F, Flaker GC, et al. Electrophysiologic testing in patients with unexplained syncope: clinical and noninvasive predictors of outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:358–63. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denes P, Uretz E, Ezri MD, Borbola J. Clinical predictors of electrophysiologic findings in patients with syncope of unknown origin. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1922–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NAM, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN. Diagnosing syncope, part 1: value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NAM, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN. Diagnosing syncope, part 2: unexplained syncope. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:76–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsitz LA, Wei JY, Rowe JW. Syncope in an elderly, institutionalised population: prevalence, incidence, and associated risk. Q J Med. 1985;216:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Maher Y, Miller RA, Levey GS. Syncope of unknown origin: the need for a more cost-effective approach to its diagnostic evaluation. JAMA. 1982;247:2687–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.247.19.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Chetrit E, Flugelman M, Eliakim M. Syncope: a retrospective study of 101 hospitalized patients. Isr J Med Sci. 1985;21:950–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;50:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calle EE, Terrell DD. Utility of the National Death Index for ascertainment of mortality among cancer prevention study II participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:235–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RN, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Report of final mortality statistics, 1995. Mon Vital Stat Rep. 1997;45:1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsitz LA, Pluchino FC, Wei JY, Rowe JW. Syncope in institutionalized elderly: the impact of multiple pathological conditions and situational stress. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:619–30. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman LS. Tables of the number of patients required in clinical trials using the log rank test. Stat Med. 1982;1:121–9. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780010204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapoor WN, Hanusa BH. Is syncope a risk factor for poor outcomes? Comparison of patients with and without syncope. Am J Med. 1996;100:646–55. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(95)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]