Managed care has become the dominant delivery system in many areas of the United States. Nearly three fourths of privately insured Americans now receive network-based health care through health maintenance organizations (HMOs), preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and various point-of-service hybrid arrangements.1 Physicians receive over one third of their revenue from managed care, and more than one third of physicians receive some revenue from capitated contracts.2

Of managed care's many features, financial incentives to physicians have received the most attention.3 Particular attention has been focused on HMOs that use risk-based capitation financing. Such financing arrangements encourage prevention and cost-effective practice, but also have the potential to discourage care that may be medically appropriate, especially if the omission of such care is unlikely to lead to other negative consequences (e.g., enrollment turnover because of dissatisfaction, revenue losses associated with malpractice cases). Policy makers are concerned that payment incentives confronting individual physicians under some managed care arrangements may distort physicians' clinical judgment.4

Health maintenance organizations vary in how much they rely on financial incentives for cost control, both alone and in combination with other mechanisms, such as utilization review and prior approval policies or broader organizational design aimed at changing physician orientation. Hillman has characterized the balance between these two approaches as the difference between incentives and rules.5 Despite some variation, virtually all HMOs depend at least in part on financial incentives using techniques like capitation, withheld funds, and bonuses.

This article discusses the current use of financial incentives in managed care. It is organized in three parts. The first part is conceptual and includes general assumptions about financial incentives and their role in managed care, a framework to provide context for them, and four key variables to use in defining the form of financial incentives. The second part is empirical and presents findings from a recent national survey of managed care plans to illustrate how incentives are structured in managed care and the organizational context in which they operate. The third part presents the observations of the author, a nonclinician researcher, and highlights key challenges facing the medical community as it decides how to respond to managed care.

Effects of financial incentives in managed care will not be discussed. Though there are several review articles on the performance of managed care, studies focused on the effects of different methods of paying physicians in managed care plans are rare.3,6–8 Rapid change in managed care organizations as well as physician involvement in a number of different health plans present substantial barriers to these types of studies. As a result, most studies have not isolated the effects of financial incentives on physician behavior from effects attributable to organizational or individual physician factors.

CONTEXT AND FRAMEWORK

Assumptions

To enhance understanding, financial incentives should be looked at in context. The following three assumptions are particularly relevant. First, all payment systems provide financial incentives to those receiving payments. In fact, any system that involves people involves some form of incentive that is derived from aspects of human behavior. The issue is not whether financial incentives should be removed, but how to anticipate their effects to identify which types of incentives may be preferable or unacceptable.

Second, the effects of financial incentives cannot be divorced from the context of their application. Most incentives have both positive and negative features, and the relative strength depends on many factors. For example, if a payment arrangement has the potential to lead to large losses for individual physicians, there are ways of limiting the amount of potential losses through measures such as a “stop-loss” provision (placing a limit on individual or aggregate patient expense) or “exceptions” (e.g., an exception for nondiscretionary care that cannot be predicted). Quality oversight features may detect faulty responses to incentives.

The environment in which incentives exist also influences their effects. The current environment is highly competitive with substantial pressure for cost containment. For example, purchasers could exert pressure on health plans to achieve substantial cost savings over a short period of time. This may be impossible to achieve, as fundamental organizational change occurs over a long period of time, and changes in provider orientation also take time. Health plans confronted by such unrealistic cost-containment expectations could respond by off-loading more risk on providers than is reasonable. Or, they might apply very strict rules of utilization management that inflame both the public and providers. Clancy and Brody have characterized the different ways in which health plans deal with these issues as the “Jekyll and Hyde” sides of managed care.9

Third, financial incentives are complex. Financial incentives are governed and defined at many levels through contracts between purchasers and health plans and among health plans, intermediate organizations, and individual providers.10 The complexity of these contracts and the many levels on which they exist create considerable risk for oversimplification or misunderstanding of the incentives for individual physicians.

Conceptual Framework

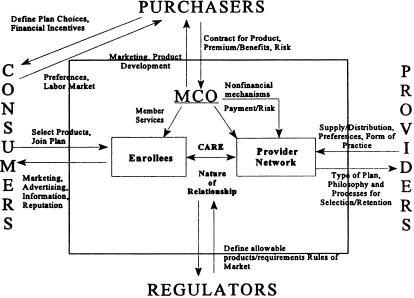

Several parties play a role in how financial incentives are structured, how they influence physicians, and their effects on patients. Figure 1 illustrates the key parties and mechanisms that define managed care and the environment in which it operates.11 Four key parties are defined: (1) purchasers, including employers and public programs like Medicare or Medicaid (and some individual enrollees), who contract with health plans; (2) consumers, who use the information available to them to select among their health insurance options; (3) providers, who are affiliated with the health plan and deliver care through the plan's network; and (4) regulators, who define the rules of the game, including which health plans and products may be offered, how health plans can choose the providers with whom they are affiliated, and the quality, access, fiscal, or other standards health plans are required to meet.

FIGURE 1.

Systems framework of managed care organizations (from Gold et al.11).

From the health care provider's perspective, the emphasis is on the far right side of the framework. This shows how provider supply within a community translates into defined managed care networks and the financial and nonfinancial arrangements that define the health plan–provider relationship. Furthermore, the arrangements between health plans and providers are determined by the types of providers found in a community, how their practices are structured, the way in which a health plan builds its provider network from among these physicians, and how the features that define the managed care plan (e.g., payments, other aspects of care, and administrative systems) are structured. For example, whether physicians practice alone or in groups and whether the market is specialty-dominated or generalist-dominated will determine whether arrangements are predominantly made between plans and physician groups (less potent incentives to individual physicians), whether capitation or utilization management are directed to specialists, or whether the principal method of cost control is reliance on generalist physician gatekeeping.

Financial arrangements vary depending on the relative bargaining strength of providers vis-à-vis health plans. Health plan preferences also may vary across markets. For example, one plan might prefer a broad provider network that may be more appealing to consumers, while another may prefer a tighter network that could enhance its bargaining power with the physicians or its ability to develop a cohesive organization. A large provider network can ensure increased availability of physicians for plan members, but individual physicians may be less responsive to any one plan because the proportion of patients in their practice belonging to that plan is relatively small. Conversely, plans that employ or contract with a limited number of physicians or physician groups should have a more direct influence on each physician's decisions, with less variation in practice patterns than for large networks. Plans also may target different niches in the market. For example, a plan may aim for the “high end” of the consumer market that has a relatively generous benefit package and expects relatively easy access to a variety of specialty providers. Alternatively, a plan may target the “lower end” of the market that traditionally has had relatively restrictive benefits, limited access to care, and substantial cost sharing.

Health plans do not make decisions in isolation. Their decisions and their negotiations with providers will be influenced by a number of purchaser preferences. These include how much purchasers are willing to pay in premiums; the premium/benefit trade-offs they are willing to accept; the amount of risk, if any, they want the health plan to bear for health care costs; and how much influence the purchaser wants in determining how care is offered and quality is measured (e.g., accreditation and reporting requirements). In responding to its purchasers, health plans also must accommodate consumer preferences, stressing features that make a health plan more or less attractive in the marketplace. Of course, the plan's decisions will be constrained by the regulatory context, which varies according to the type of purchaser.

Ultimately, all of these factors affect both the process of care and the enrollee-provider relationship, as depicted in the middle of the framework. In traditional plans, financing arrangements affected care mainly through their influence on what was covered; there was no other link to delivery. In managed care, financing and delivery are combined. The financing entity (health plan) also establishes the structures that affect the way in which providers and patients access one another and the financial and other mechanisms that influence the care provided and potentially its outcomes. Thus, to function effectively in a managed care environment, physicians must understand these structures as well as the incentives and rules that go along with them.

Four Variables That Define the Form of Financial Incentives

The financial incentives in managed care are complex. Four key variables can be used to identify their form in a specific context: the form of the provider network, the basic payment method for physicians, the use of withheld funds or bonuses, and the limitation on risk or loss.

The Form of the Provider Network and Practice

Health plans may contract with physicians individually or in groups; further, they may do so directly or through an intermediary. Payments to individual physicians are sometimes direct (“two-tier plan”), and sometimes indirect (“three-tier plan”); HMOs that contract directly with individual physicians are “two-tier” plans, and HMOs that contract indirectly through intermediate provider groups or various medical independent practice associations (IPAs) are “three-tier” plans.

The extent and form of the practices that make up a health plan affect the size of provider “risk pools,” which in turn affect how a plan will structure incentives. A “risk pool” can be defined as the number of individual physicians that are paid collectively and thus share financial risk for the costs of patient care. From an actuarial standpoint, large pools are less risky because they are likely to include more enrollees and thus lower the risk of financial loss to an individual physician as a result of a patient's catastrophic illness or accident.

In establishing provider payment arrangements and defining risk pools, many health plans distinguish between primary care and specialty physicians, though they may define them differently. Payment arrangements for each will reflect the responsibilities of physicians and the way in which patients reach them. For example, a primary care gatekeeper model probably is a precondition for individual capitation of primary care providers (PCPs), but plans may vary in how they define the services that PCPs must authorize.12

The Basic Payment Method for Physicians

Physicians may be paid on a fee-for-service (FFS), capitation, or salary basis. Each of these has its own set of incentives. Fee-for-service payment provides natural incentives to be productive and efficient but may encourage physicians to give more care than is needed. Capitation encourages providers to serve more patients but to use fewer services for each, particularly when such services are expensive. Few plans, if any, capitate individual physicians fully for all services; they typically apply limits in various forms, with hospitalization and referral expenses often excluded fully or in part. Salary arrangements provide limited incentives for provider productivity, as physicians are paid the same amount no matter how many patients they see. Recently, some health plans that have been structured around salary arrangements with a physician group have divested themselves of these groups in favor of other payment arrangements that have lower fixed costs. This allows the plan more flexibility to respond to market competition.

The Use of Withheld Funds or Bonuses

To offset the negative features associated with basic forms of payment, managed care plans often use incentive payments. For example, salaried physicians may be rewarded with additional funds (a bonus) on the basis of productivity. Capitated primary care physicians may receive incentives to be conservative in using referral or hospital services, and FFS physicians may be rewarded when the plan, the provider group, or individual provider does well on various measures like cost, utilization, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. For example, part of the payment may be withheld and only distributed when certain performance targets are met.

The Limitations of Risk or Loss

Health care spending is skewed; i.e., most individuals spend little in any year, and a few spend a great deal. Some of this variation occurs randomly (e.g., through accidental injuries), while some reflects systematic differences across individuals (e.g., chronic disease). For example, internists tend to attract older patients, and minority physicians tend to attract a higher proportion of sick and poor patients than nonminority physicians do.13 Both have implications for payment and equitable treatment of providers. To address random variation, actuaries can calculate, for any given size of patient panel, the probability that a provider will experience a loss of a given size by chance alone. To be equitable, a provider contract may limit losses beyond a certain amount either per patient or in aggregate. It is more difficult to adjust for systematic variation—the variation in patient mix across providers that predictably affects costs. In the interest of equity, capitation rates may be set differently for providers who serve certain categories of patients. However, while some adjustments (for age, gender, or family composition) are relatively easy, others that focus more closely on actual health status are harder to make because both methods and data are poorly developed.

The way in which a plan structures its arrangements using these four variables, combined with arrangements developed by physician group practices or intermediaries, will jointly influence the form of financial incentives for a physician. Plans may use a mixture of basic payment methods to provide specific incentives, including salary, FFS, or capitation. Often FFS is discounted or modified by utilization management for selected procedures. Preventive care may be paid for on a FFS basis to encourage its use while other services are capitated. Specialized services, such as endoscopy, may be included in capitation rates for some physicians but excluded for others. Factors likely to influence which services are included in capitation rates could include the physician's comfort level with doing the procedure, practice patterns in a particular market area and whether a plan chooses to contract with a limited number of physicians for selected procedures. When plans contract with physician groups or intermediaries, the method of payment to an individual physician may differ from that provided to the group or intermediary. For example, an individual physician working within a group practice that receives capitation from a plan may be paid by the group practice on an FFS, salary, or capitation basis, or some combination of these.

Further, the ways in which incentives affect individual physician behavior are likely to be influenced not only by how that physician is paid but also by other factors such as the physician's personal characteristics, training, and knowledge or assumptions about the incentives. Broader characteristics of the organization in which a physician practices may also influence treatment patterns. These are presumed to include the organization's culture, nonfinancial incentives resulting from administrative and care-delivery features of the health plan (e.g., utilization review and management, profiling, or quality improvement systems), and the market, norms, and expectations under which the plan operates. These features may be centrally defined by the health plan or determined by any or all of the multiple intermediate entities, such as IPAs or physician-hospital organizations (PHOs), with which a physician may be affiliated.

EMPIRICAL ILLUSTRATION OF STRUCTURES

The most comprehensive and detailed profile of managed care incentive plans was conducted in mid-1994. One hundred eight plans, from a stratified, random sample of 108 managed care plans in 20 markets, were studied. Three types of plans were included: group or staff-model HMOs (defined as plans that directly hire physicians or contract exclusively with a single physician group); network or IPA HMOs (defined as plans that contract with individual physicians or one or more physician groups on a nonexclusive basis); and PPOs (defined as plans that contract with individual physicians for fee discounts; the plan usually does not assume financial risk). Lengthy telephone interviews of up to three clinical and administrative leaders identified by each plan's chief executive officer were conducted.6,11 Both network/IPA HMOs (now the predominant managed care arrangement) and group/staff-model HMOs were much more likely than PPOs to have payment arrangements that departed from traditional FFS and to employ other kinds of managed care features.

Provider Network Context

The financial incentives in managed care vary substantially with the form of provider network in place. Many of these networks are quite complex and diverse in ways that defy simple description. In contracting with physicians, 53% contracted both directly and through intermediate entities.

Often HMO structures distinguish their payment approach for PCPs separately from specialists. In the HMOs studied, over 90% of PCPs were held responsible for referrals to specialists. In networks/IPA HMOs, these responsibilities were typically assigned to individual physicians, with 92% requiring patients to choose a PCP. In contrast, some group/staff-model HMOs appeared to place these responsibilities more broadly at the group or primary care practice level, as only 61% in group/staff-model HMOs required choice of individual physician. Of plans surveyed, 58% of network/IPA HMOs, 50% of group/staff-model HMOs, and 21% of PPOs said they had taken specific steps to change the scope of primary care practice.

Basic Payment Arrangements

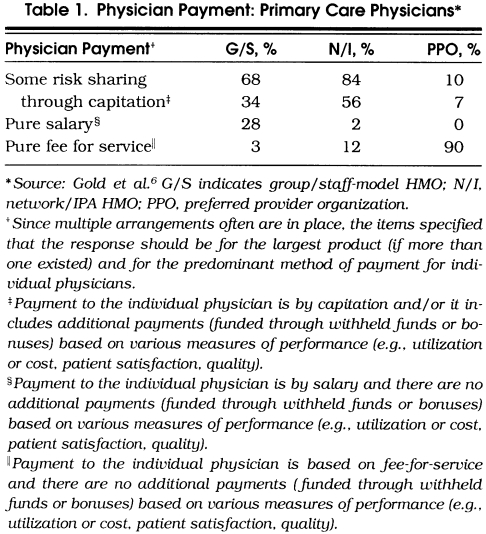

As shown in Table 1, risk sharing with PCPs was common in both group/staff-model HMOs and network/IPA HMOs in 1994, but not very common in PPOs. We defined risk sharing as paying physicians using capitation or employing withheld funds or bonuses (also called incentive payments). Only 10% of PPOs provided incentives. This is not surprising, as PPOs typically are not paid on a capitated risk basis by purchasers, leaving them less incentive to transfer risk to individual providers. Rather, PPOs most often organize groups of providers who have agreed to provide services on a discounted FFS basis. In addition, such arrangements often are precluded by state laws. Among network/IPA HMOs, however, 84% had some risk sharing with PCPs and 56% did so through capitation. Only 12% used pure FFS with no other incentive payments.

Table 1.

Physician Payment: Primary Care Physicians*

Although the survey items asked about payment arrangements for individual physicians regardless of whether they went through intermediate entities, we were not able to capture what the capitation payments covered. Among network/IPA HMOs paying PCPs on a capitation basis, 84% adjusted the rate by age and gender and 69% by payer. Adjustments based on health status or pregnancy (18% each of plans) were the exception. Seventy-six percent provided a patient-level stop loss, and 38% provided an aggregate-level stop loss; all network/IPA HMOs used at least one or the other.

Further incentive payments for PCPs were common in both kinds of HMOs. While 74% of network/IPA HMOs provided withheld funds or bonus payments based on measures of use or cost of services, other measures also are typically employed in these distributions. These include quality of care (61%), patient complaints (61%), consumer surveys (55%), enrollee turnover (36%), and provider productivity (26%). The evidence suggests that incentive payments based on quality or consumer satisfaction represent less than 10% of total income. In addition, the results are not verified and may overstate the use of quality measures to balance financial incentives.6

Incentive payments also are common in group/staff-model HMOs, reflecting a change from the most common historical practice of purely salaried arrangements. Fifty-seven percent of group/staff-model HMOs had incentives linked to patient complaints, 54% based on quality, and 50% based on measures of use or cost.

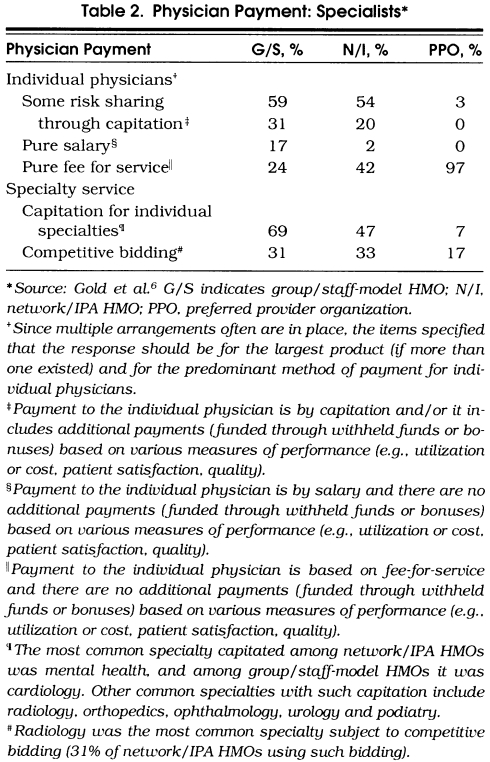

In addition to incentives for PCPs, reimbursement methods for specialists are also an important dimension of the impact of financial incentives. Risk sharing between HMOs and physicians using capitation was infrequent for specialists, but relatively common for PCPs (Table 2). Among network/IPA HMOs, 54% had some risk sharing with individual specialty physicians. While 20% of plans used capitation, 34% provided incentives to specialists through withheld funds or bonuses to complement FFS payments. More, however, were using capitation for groups of specialists (47%). The most common specialties were mental health, radiology, podiatry, and cardiology. Risk sharing with specialists has been increasing over time.

Table 2.

Physician Payment: Specialists*

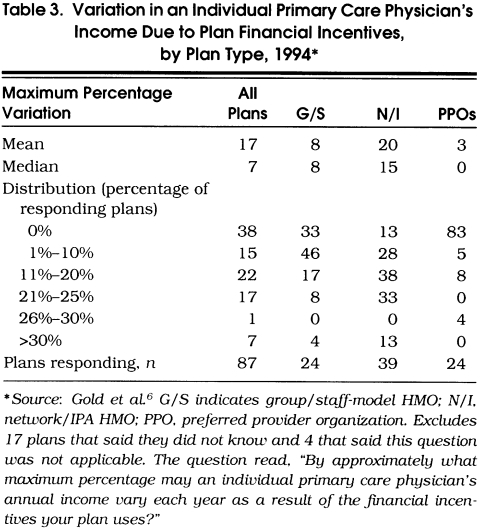

Aggregate Risk and Incentives

The survey data provide less insight about how much total risk the HMOs were transferring to physicians. In an effort to identify the amount of risk facing a physician, we asked plans what maximum percentage an individual physician's income could vary due to financial incentives (Table 3). Network/IPA HMOs clearly shared more risk than other plans with a mean of 20% and median of 15%. However, network/IPA HMOs varied considerably. Thirteen percent shared no risk, and 28% had arrangements that they indicated would affect physician income by a maximum of 10% or less. In contrast, 13% of plans said income could vary by more than 30%. Risk is a complex concept, and it is not clear how closely the responses represent the net impact of multiple financial incentives to physicians. Some have argued, for example, that the level of capitation and its adequacy is at least as or more important to a physician's risk than any withheld funds or additional bonus.14

Table 3.

Variation in an Individual Primary Care Physician's Income Due to Plan Financial Incentives, by Plan Type, 1994*

Context in Which Financial Incentives Operate

Structures are in place in many managed care plans that are likely to influence the way in which financial incentives operate. It is important to note that a survey can only identify what plans report they do by way of structures and incentives for physicians, not how well they do it or how it is understood by the individual physician.

Structures and processes for quality improvement and oversight exist in almost all the HMOs and many PPOs. The vast majority of HMOs and from 72% to 79% of the PPOs had quality assurance committees in place. They also had written quality assurance plans and active patient grievance procedures. Over 90% of the HMOs (59% of the PPOs) had targeted quality improvement initiatives. More than 90% of the HMOs, and 55% of the PPOs, conducted consumer surveys. Almost all the HMOs and 45% of the PPOs said they conducted clinically focused studies on a regular basis. These studies are used to respond to external review and regulatory requirements (as well as purchaser effects). They are also used internally to identify areas for improvement and to gauge success. To some extent, these surveys may be developed in response to requests from large purchasers who are asking about quality and requiring accreditation from groups such as the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA).

Plans also were active in a number of other clinically related areas that may influence physician practice patterns, quality, or costs. Eighty-six percent of network/IPA HMOs, 76% of group/staff-model HMOs, and 52% of PPOs said they profiled practice patterns. Profiles most commonly were used to identify areas for systemwide improvement, provide physician feedback, screen outliers for review, and make decisions on contract renewals. In addition to inpatient utilization review, 72% of network/IPA HMOs, 83% of group/staff-model HMOs, and 55% of PPOs required ambulatory utilization review for resource-intensive services such as magnetic resonance imaging. Slightly more than half of the network/IPA HMOs (52%) and 66% of group/staff-model HMOs required preauthorization for specialist referral.

OBSERVATIONS AND DISCUSSION

Managed care plans, especially in HMOs, change important features of the health care delivery system that influence the way physicians provide care. Through complicated and multidimensional arrangements, HMOs enter into risk-based agreements with physicians. Using a varying combination of capitation and incentive payments (and salary for group/staff-model HMOs), HMOs establish an environment that encourages physicians to practice differently than they would in traditional FFS systems. Payment features are intended to encourage physicians to provide care judiciously but with concern for quality, outcomes, and patient satisfaction. These features are reinforced by other practices, such as peer profiling and prior approval requirements. Still, the basis for determining physician payment remains relatively primitive, with limited risk adjustment and uncertain actuarial analysis underlying physician risk sharing.

Managed care, especially in HMOs, includes explicit financial and nonfinancial incentives to encourage physicians to focus on quality and consumer satisfaction. This includes policies that provide incentive payments (albeit small) based on these measures, as well as active quality assurance activities that have the potential to examine an entire population of enrollees, not only active users. These aspects of managed care tend to be absent in traditional FFS practice and could provide a major opportunity to enhance quality.

Considerable controversy continues to surround the issue of financial incentives and managed care. As a nonclinician researcher, I find it helpful to view this controversy in the context of some basic premises. First, physicians are not disinterested parties in assessing financial incentives. Each physician has a financial stake in the outcome. Many physicians, specialists, in particular, are finding it difficult to maintain their incomes and their practices in the current reimbursement environment. Separating financial self-interest from the physician's role as patient advocate is important. Without this, physicians may run the risk of having decision making about patient care depend on the competing influences of physicians' financial interest versus the patients' physical and mental well-being. The potential negative impact on patients' trust in their physicians is an important policy issue.15

Second, what is best for an individual patient is not always what is best for society, particularly when resources are scarce and payers are increasingly unwilling to pay unlimited expenses. Although it is not clear how physicians should define their obligations in this context, explicit recognition of this conflict would be helpful.16,17 Third, we are in a transition period. Although managed care has developed rapidly, many plans are still relatively immature. Improvements and self-corrections are likely to occur with experience. Some negotiation and balancing between physicians and health plans, as well as other stakeholders, can be argued to be both inevitable and healthy. The resulting changes will create more consistent connections between what purchasers want to buy from health plans and what health plans' providers deliver, while at the same time making sure that physicians don't bear so much risk that patients are denied needed care.

Finally, the focus on financial incentives should not obscure the key concepts of accountability and population-based measurement that are inherent in the capitated managed care model. Whatever its faults or limitations, managed care, at least conceptually, puts the focus on health needs rather than reimbursable services because health plans are capitated to serve enrollees. In my experience, few physicians understand capitation and its focus on an enrolled population. For example, a physician might compare the capitation rate for a patient with that patient's use of services and complain when the latter exceeds the former. The same physician might fail to account for patients who use few services.

In conclusion, financial and other incentives used by managed care organizations can encourage providers to be more sensitive to the entire population they serve and to the outcomes of care for that population. Strategies that encourage physicians to match intensity of care with patients' needs and preferences are changing as rapidly as the alphabet soup of plan labels. Physicians, therefore, have the opportunity and the responsibility of influencing managed care to ensure that their patients' interests receive the highest priority.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to the Physician Payment Review Commission for supporting some of the underlying research on which this paper builds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jensen G, Morrisey M, Gaffney S, Liston DK. The new dominance of managed care: insurance trends in the 1990s. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(1):125–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon C, Emmons DW. Physician earnings at risk: an examination of capitated contracts. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(3):120–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillman AL. Financial incentives for physicians in HMOs: is there a conflict of interest? N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1743–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712313172725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annual Report to Congress . Washington DC: Physician Payment Review Commission; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillman A. Managing the physician: rules versus incentives. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10(4):138–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.4.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold MR, Hurley R, Lake T, Ensor T, Berenson R. A national survey of the arrangements managed care plans make with physicians. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1678–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller R, Luft H. Managed care performance since 1980: a literature analysis. JAMA. 1994;271:1512–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller R, Luft H. Managed care performance: is quality of care better or worse? Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(5):7–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clancy CM, Brody H. Managed care: Jekyll or Hyde? JAMA. 1995;273:338–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum S. A look inside Medicaid managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(4):266–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold M, Nelson L, Hurley R, Berenson R. Behind the curve: a critical assessment of how little is known about arrangements between managed care plans and physicians. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52:307–41. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felt-Lisk S. How HMOs structure primary care. Managed Care. 1996;4(4):96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273:1515–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berenson R. A physician's view of managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10(4):106–19. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.4.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mechanic D, Schlesinger M. The impact of managed care on patients' trust in medical care and their physicians. JAMA. 1996;275:1693–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halm EA, Causino N, Blumenthal D. Is gatekeeping better than traditional care? A survey of physicians' attitudes. JAMA. 1997;278:1677–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MA, Berenson RA. Ethical practice in managed care: a dose of realism. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:395–402. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-5-199803010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]