A physician who is called upon to consult, should observe the most honorable and scrupulous regard for the character and standing of the practitioner in attendance: the practice of the latter, if necessary, should be justified as far as it can be, consistently with a conscientious regard for truth, and no hint or insinuation should be thrown out, which could impair the confidence reposed in him, or affect his reputation.

—1847 Code of Ethics, American Medical Association

Good relationships among physicians are essential for good patient care.1–3 However, the new organizational and financial realities of American medicine are dramatically changing the rules by which physicians interact with each other. With these changes have come new or reinforced tensions that have seriously strained many aspects of physician-physician relationships. Patients, money, prestige, autonomy, power—the state of all these and more seems uncertain as the old patterns of a profession organized largely as a cottage industry are swept away.

There are many dimensions to physician-physician relationships, including competition for patients and hospital privileges, postgraduate training, the management of impaired colleagues, peer review, the establishment and enforcement of the boundaries of professional behavior, and the role of organized specialty societies. However, a single specific interface between physicians has dominated the profession's concerns in the wake of managed care: the interface of consultation between generalists and specialists.4–6

The interface between primary and specialty care is a critical fulcrum in medical decision making on which hinge many decisions about the use of the most effective—and expensive—tests and treatments available. In addition, most evidence seems to support the conclusion that specialists perform more tests and procedures than generalist physicians caring for comparable patients.7, 8 There is thus no surprise that managed care organizations, in seeking to maximize the cost-effectiveness of care, have attempted to actively manage the boundaries between primary and specialty care. Health plans have introduced referral networks, subcapitation schemes, primary care withholds for referral services, prior authorization requirements for referrals, referral guidelines, telephone and teleconference specialty “hotlines”—all these techniques and more have been grafted into position to control the primary care–specialty care interface.

This target of managed care's reengineering is a relationship that has been no stranger to tension. Generalists and specialists have always faced conflicts in competing for patient loyalties, professional prestige, and compensation. But these tensions have been pushed to the brink of professional warfare by the scope and speed of changes mandated by managed care.4 Generalists, basking in the glow of managed care's emphasis on primary care, have openly applauded their new-found respect: “The opportunity to take center stage in patient management is welcomed by generalists.”9 Specialists, meanwhile, acutely aware that demand for their services is declining under managed care, defend their clinical role with vigor: “The silent accumulation of extended responsibility and the failure to keep truly up-to-date with all claimed competencies will lead to the eventual undoing of primary care.”10

Strong words reflect the depth of the concern about the effects of managed care on the balance between primary care and specialty care.11 Nonetheless, the medical profession, not only for its own self-interest, but also because of its primary ethical duty to care well for patients, has an obligation to avoid self-defeating acrimony and seek rather to define the principles that will guide generalist–specialist relationships toward the best interests of patients. The medical profession must also ensure that these principles are clearly and effectively transmitted to all physicians in training.

The Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Managed Care Task Force addressed these challenges during its precourse at the 1997 National Meeting in Washington, D.C. This article, drawn from a presentation given at the precourse, reflects the opinions of its sole author, a general internist. My ideas have been tempered, however, by feedback from SGIM members in attendance at the precourse, and by helpful comments on early drafts of this article by subspecialty colleagues within my group practice. My goal is to present for discussion a set of principles that promote excellence in patient care by fostering the highest professional standards in the relationship between generalist and specialist physicians.

SOURCES OF PRINCIPLES

Principles guiding physician-physician relationships can be found in the earliest expressions of moral codes guiding the medical profession, beginning with the Hippocratic oath. Principles related to the particular relationship between generalists and specialists find their best-known early delineation in the work of the English physician and ethicist Thomas Percival, whose 1803 code of medical ethics included detailed guidelines for the behavior of consultant and attending physicians in an amalgam of bourgeois sense and gentlemanly sensibility.12 The early versions of the “Code of Ethics” of the American Medical Association (AMA) were modeled after Percival's work, and included extensive sections related to the etiquette of interactions between attending and consultant physicians.13

More recent versions of the AMA Code of Medical Ethics, however, have jettisoned much of the earlier emphasis on relationship etiquette, and there is very little left that provides specific direction regarding the proper relationship between generalist and specialist physicians. Another codification of professional ethics, American College of Physicians Ethics Manual (1992), does include many helpful statements on the relationship between referring and consulting physicians but does not relate these guidelines to recent developments in medical systems brought about by managed care.14

Generalists, specialists, and health services researchers have published numerous articles in the medical literature, some of which report data related to consultation practices, and others that comment on the ideal process of consultation.15–19 None of these articles, however, has attempted to define more general principles of the generalist–specialist relationship.

The principles delineated in this article draw heavily for inspiration from all of these formal and informal sources, and some have been extracted virtually word-for-word from these earlier sources, particularly from the American College of Physicians Ethics Manual. Some principles are new in spirit or detail, but I hope all reflect the new perspectives on the relationship between generalists and specialists that have been gained in the last several year's experience with managed care. Italics have been used in the tables to demonstrate those principles that are new in spirit, and to identify elements of previously enunciated principles that have been significantly changed from their previous incarnations.

Many of the principles are presented here as prima facie principles: that is, it is assumed that the reader will find their justification to be self-evident. Other principles, however, require explanation and formal defense. All these principles, however, old and new alike, are expressly based on an a priori hierarchy in which the individual patient's well-being is the highest goal. This goal therefore inspires, guides, and shapes my arguments for the ideal specific forms of the relationship between generalist and specialist physicians.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

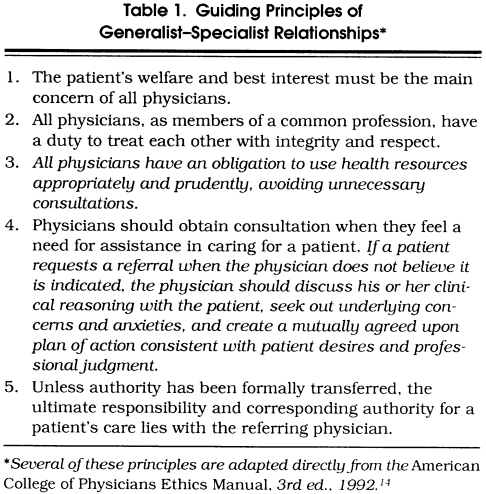

The general guiding principles for the relationship between generalists and specialists that set the framework for all other principles are displayed in Table 1. As mentioned, first and foremost presides the principle that the patient's welfare and best interest must be the main concern of all physicians. This is the dominant and orienting principle that grounds all other secondary and derivative principles in the primary ethical obligation of physicians: to do good for their patients.

Table 1.

Guiding Principles of Generalist–Specialist Relationships

The second guiding principle for the relationship between generalist and specialist physicians demands that they treat each other with mutual integrity and respect. These attributes are necessary to build the trust and communication required for good patient care. Whatever the fluctuations in money, power, and prestige between generalists and specialists, common and even uncommon courtesy should be the norm. Without this basic building block in the foundation of their relationship, the ability of physician teams to work together to care well for patients would be crippled.

The third general principle confirms the societal obligation of all physicians to use health resources appropriately and prudently; and thus, physicians must avoid unnecessary consultations. Sending a patient to see a specialist in order to curry favor—even if done to improve professional relations—is rarely in the patient's best interest, and certainly abrogates the physician's duty to use societal resources wisely. Equally, consultations solicited or generated by the specialist primarily to obtain a source of teaching cases or income is highly unethical.

Physicians should obtain consultation whenever they feel a need for assistance in caring for a patient. Clinical guidelines, reimbursement issues, even the threat of deselection from a health plan cannot override physicians' duty to obtain help if they think they need it. If a patient requests a referral in a situation in which the physician does not believe that it is indicated, the physician should discuss his/her clinical reasoning with the patient, seek out underlying concerns and anxieties, and create a plan of action that can be mutually agreed upon.

Adherence to this principle is critical in those managed care settings in which a gatekeeper system restricts patient's direct access to specialists. Take, for example, the case of a patient with a gatekeeper health plan who requests referral from the primary care physician to see a neurologist for a headache condition. If, after a thorough physical examination and careful listening and exploring of the patient's concerns, the physician firmly believes that a trial of empiric treatment is indicated rather than immediate referral, what should the physician do to act ethically as the patient's advocate? The answer is clear: the physician should communicate his/her clinical rationale to the patient and work to design a plan in which the threshold for future referral is made clear and the patient is satisfied. In arriving at this plan, the physician should always be sensitive to potential patient concerns about the influence of financial incentives on referral decisions, and the physician must be able to address such concerns effectively. In sum, it is certainly not in patients' best interest for physicians to summarily deny referral on the grounds of clinical superiority, but neither is it in patients' best interest for physicians to abdicate their professional role and cravenly accede to patients' requests.

The final general guiding principle for the relationship between generalist and specialist physicians places the ultimate responsibility and corresponding authority for a patient's care squarely in the hands of the referring physician. Why should this be? Doesn't the consultant physician usually have superior experience and skills in the area of immediate concern to the patient's health? The idea behind this principle is not to establish a lock-step hierarchy with the generalist leading the way. Rather, the goal is to reinforce the key concept of accountability for the patient's care. Too many patients are discovered to have been lost to follow-up, or “lost through the cracks,” owing to a failure that can be labeled one of communication but is ultimately a failure of personal accountability on the part of physicians.20, 21 And accountability begins—and most often remains—with the referring physician. Primary authority and accountability for a patient's overall care may be transferred, sometimes indefinitely, to a specialist physician, but unless such a transfer has occurred, with clear acknowledgment by both physicians and by the patient, the ultimate accountability and corresponding authority for a patient's care lies with the referring physician.

CONSULTATION AND REFERRAL

Joint Duties

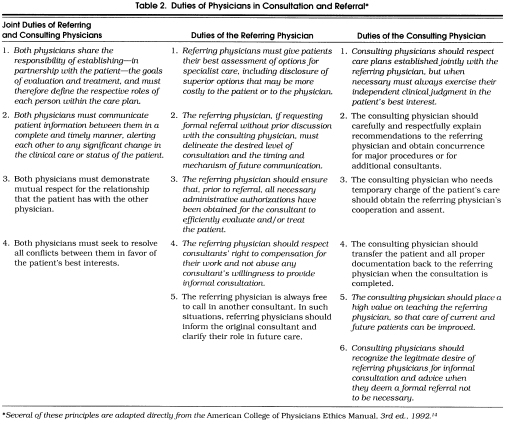

Building on the guiding principles outlined above, more specific duties of physicians in the consultation and referral process can be added. Table 2 shows these duties, categorized by whether the duty is incumbent on the referring physician, the consulting physician, or both jointly.

Table 2.

Duties of Physicians in Consultation and Referral*

Certain duties are fully shared by both the referring and the consulting physician and best considered as joint responsibilities. For example, both physicians share the responsibility of establishing, in partnership with the patient, the goals of evaluation and treatment. Although the referring physician often takes the lead in setting expectations for the consultation, both physicians must ultimately take part in the process of communicating with each other and with the patient about the respective roles of each person within the care plan.

Both physicians must communicate patient information between themselves in a complete and timely manner, alerting each other to any significant change in the clinical care or status of the patient. Many physicians have experienced the pain of finding out hours or days after the fact that a patient under their care has been admitted to the hospital or has died. Missed opportunities to communicate with the patient or family at such critical times can never be regained, and caring physicians feel as if they have violated their patient's trust. It should be stressed that this duty is shared by referring physicians. Consulting physicians have doctor-patient relationships that are just as deserving of respect in this regard, and consultants should be informed of major changes in their patients' status, even if referring physicians remain primarily responsible for the patients' care.

Both physicians should demonstrate a broad respect for the relationship that the patient has with the other physician. Unless incompetence or impairment presents a direct threat to the patient's health, physicians should refrain from denigrating the character or clinical skills of any physician with whom their patient has a relationship. The value of the patient's relationship with other physicians cannot be fully appreciated by another physician, and even casual aspersions may deeply confuse and trouble the patient. The patient's best interests can almost always be served by working in a positive and respectful fashion with their current physicians.

This leads to consideration of conflict between referring and consulting physicians. Both physicians share an obligation to resolve all conflicts between them in favor of the patient's best interests. Any dynamic relationship is going to have tension and conflict. It should. Differences in opinions need to be shared in order for patients to have the full benefit of consultation and to be able to participate in their care. Conflict needs to be resolved, however, not with physician's authority or prestige foremost, but with the patient's best interest always in mind.

Duties of the Referring Physician

When contemplating referral, the referring physician has a deep and abiding duty to give patients their best assessment of options for consultant care. These may include superior options outside the patient's health plan that would thus be more costly to the patient or to the physician, depending on the financial arrangements under the plan. Underlying this duty is the belief that patients should be treated as autonomous persons, able to make their own decisions about where to spend their time and money, and no conflict of interest on the part of physicians should keep them from giving their patients information about all their options.

If the referring physician sends a patient for a consultation without prior discussion with the consulting physician, the referring physician should delineate in writing the desired level of consultation and the timing and mechanism of future communication. Specialists can cite numerous examples of patients arriving for a first consultation with an illegible referral slip, not knowing why they are there. Referring physicians can also create great confusion if they forget to indicate whether they are sending a patient for a one-time visit or whether they want the consultant to take over longitudinal care for the management of the patient's complaint. The referring physician must communicate this information, as well as clearly defined clinical questions and appropriate medical history, to the consultant.

The referring physician, or suitable office staff, should also communicate directly with the consultant or the consultant's office to help obtain, prior to referral, any administrative authorizations necessary for the consultant to efficiently evaluate and treat the patient. It is obviously not in patients' best interest to be sent for a diagnostic procedure, only to find on arrival that the consultant cannot perform the procedure because appropriate approvals have not been obtained from the health plan.

Referring physicians often count on their consultant colleagues for informal consultation and advice. Such teaching and sharing of clinical advice is an integral part of good generalist-–specialist relationships. However, referring physicians have the duty to respect consultant's general right to compensation for their knowledge and skills. Under capitated incentives, generalists may be tempted to ask consultants for extensive input into the management of patients that the generalist is unwilling to send for a formal referral. A balance needs to be struck, and part of that balance is the referring physician's duty not to abuse any consultant's willingness to provide informal consultation. Specific guidelines related to appropriate levels of informal consultation must be designed to reflect the local practice environment and the compensation model employed.

The referring physician is always free to call in another consultant. In such situations, the referring physician should inform the original consultant and clarify his/her role in future care. If, after referral, a patient asks the referring physician for a second specialty opinion and the request is granted, the referring physician should inform the first specialist of this event. If, on the other hand, a patient requests a second specialty opinion from a specialist, the specialist should ask the patient to discuss the request first with the referring physician.

Duties of the Consulting Physician

Consulting physicians should respect care plans established jointly with referring physicians, but when necessary must always exercise their independent clinical judgment in patients' best interest. For example, if a cardiologist sees a patient for whom the referring physician has requested a cardiac catheterization, the cardiologist's first instinct should be to determine whether honoring the request would be in the patient's best interest. If the cardiologist believes that catheterization is not indicated, then he/she should communicate with the referring physician to explain and to mutually determine the next step in the patient's care. In a time when referral sources are highly prized, consultants must still use their professional judgment in the patient's best interest, superseding any desire to satisfy or placate a referring physician.

The consulting physician should always carefully and respectfully explain recommendations to the referring physician and obtain concurrence for major procedures or for additional consultants. A consultant who needs temporary charge of a patient's care must obtain the referring physician's cooperation and assent, and should always transfer the patient and all proper documentation back to the referring physician when the consultation is completed. Generalist physicians who have had even one or two patients return without adequate documentation of what the consultant has done know the confusion and poor care that can result.

Duties of Health Plans

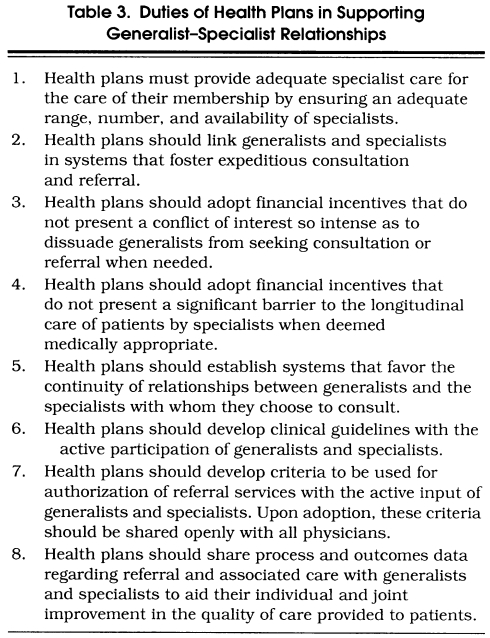

What is the role of health plans in the generalist–specialist relationship? Whereas in the past the hospital as an institution wielded significant power in shaping the interaction between generalists and specialists, the advent of managed care has dramatically increased the power and the range of activities of health plans in this domain. Like physicians, then, health plans have specific duties of their own in fostering high professional standards among physicians and in establishing consultation processes that provide optimum care. Table 3 shows a list of duties for which health plans should be accountable, given their power in shaping generalist–specialist relationships.

Table 3.

Duties of Health Plans in Supporting Generalist–Specialist Relationships

Most basically, health plans have the duty to provide adequate specialist care for their patients. To do this they must ensure adequate specialist manpower to meet the needs of the enrollees and affiliated generalist clinicians. Health plans also should create specific systems that foster effective relationships between generalists and specialists. For example, the approval mechanisms for specialty care should be streamlined so that generalists and specialists easily can tailor care to the needs of individual patients. A good system will mean that patients will not have to run back and forth between physicians just to get forms filled out for ongoing care.

Several other health plan features affecting generalist–specialist relationships merit particular attention. Financial incentives are an important place to start. The structures of benefit packages and financial incentives in managed care are tremendously diverse and likely to continue evolving, and the generalist–specialist relationship will be buffeted by this ever-changing environment. Incentive systems currently being used by health plans, however, such as primary care capitation with a withhold for referral services, do introduce potential financial costs to the generalist for sending a patient to a specialist for a consultation.22 These incentive systems have been noted as having a potentially chilling effect on the sharing of patients by generalists and specialists.23 To date, there are no firm data to suggest that patients receive inferior care under such systems, but anecdotal evidence is clear that the relationship between generalists and specialists has often suffered.4 On the other hand, there are other anecdotal reports of financial incentive systems, such as specialist capitation, that seem to have fostered increased communication between generalists and specialists, including more teaching as specialists find it in their best interest to train their generalist colleagues to be as skilled as possible to handle more routine cases.24

In whatever form the financial incentives within a health plan are crafted, as a principle it is clear that health plans should adopt financial incentives that do not present a conflict of interest intense enough to restrain generalists from seeking appropriate expertise when needed. As a corollary, the incentives must also not present a significant barrier to longitudinal care by specialists should that be deemed medically appropriate by the patient and the generalist–specialist team.25

An important feature of many health plans is the selection of a closed network of generalists and specialists to serve an enrolled population. These selective networks can mean that historical generalist–specialist referral relationships are not covered by a health plan. For example, rather than referring a patient with increasing angina to a known and trusted cardiologist, generalists must now sometimes refer the patient to a specialist they have never met, one whose practice style, interpersonal skills, and general competence are unknowns to them.

Does patient care suffer when health plans mandate the use of specialist providers other than those known to the generalist? Again, no data are available to confirm or reject this possibility. Nevertheless, if we assume that good generalist–specialist relationships benefit patients through improved communication and coordination of care, then health plans should foster, whenever possible, continuity of relationships between generalists and specialists. “Carving out” specialty services previously provided within an integrated multispecialty group practice creates particularly high risks for interrupting collegial relationships that are likely to be beneficial for patient care. If a health plan does carve out specialty care in a particular domain, the plan must consider the effects on generalist–specialist coordination of care and take steps to ensure that lines of communication are clear. Whenever possible, health plans should avoid the potential for extra confusion and poor coordination caused by frequent shifting of carved out services among different vendors.

Another feature of health plans that affects the generalist–specialist relationship is the development and adoption of clinical guidelines. Many guidelines directly or indirectly recommend patterns of care that affect referral to specialists. In order to gain insights from multiple perspectives and thus improve communication and coordination of care, health plans should always include representatives from generalist and specialist physician groups in the creation of these guidelines. Similarly, any criteria being developed for authorization or approval of referral services should be developed with input from both generalists and specialists, and then made openly available to all participating physicians.

Health plans can also help foster high standards of communication and care between generalists and specialists by sharing process and outcomes data with physicians from both groups. Data on referral rates, procedure rates, and patient outcomes and satisfaction ratings support professional standards of quality improvement better than anecdotal jousting, and can therefore serve as an important foundation for generalist–specialist work groups to improve the quality and efficiency of care for all patients.

Both generalist and specialist physicians should attempt to contract preferentially with health plans that foster high-quality care through policies and practices that support effective relationships among all physicians. Physicians who believe that health plans in which they participate are not fulfilling their duties in this regard should join with their colleagues to advocate actively for changes that will improve their ability to provide the best care they can for their patients.

INNOVATIONS

If the advent of managed care has presented new challenges to the generalist–specialist relationship, it has also spurred tremendous innovation and spawned numerous new programs to improve generalist–specialist relationships and specialty care overall.26 Multispecialty physician groups, physician-hospital organizations, and other managed care entities seeking to function as smoothly integrated health care systems have had great incentives to try new ways to improve all elements of care between generalists and specialists. Although there are no rigorous data yet to evaluate specific innovations, some of the general approaches being tried are worth mentioning because their goals strongly support the principles presented here.

Many medical groups have taken specific steps to improve communication between generalists and specialists. Just arranging for regular meetings between representatives of generalist and specialist physicians can be an important start. From such humble beginnings, quality improvement groups in many medical groups have devised new and better ways for generalists and specialists to work together. For example, to reduce unnecessary referrals while improving physician-physician communication and patient satisfaction, some groups now use dedicated beeper numbers manned by specialists to provide easy and timely telephone consultation to primary care physicians. Some of the larger medical groups have even established in-house specialists who can be paged to come at a moment's notice to see a patient in a generalist's office. Medical groups are also designing new structured referral forms and decision-making supports for generalists to ensure that the generalist has performed recommended care prior to referral, that the generalist's request is fully and accurately communicated, and that the specialist has all the information necessary to care for the patient well and expeditiously.7, 27

As previously mentioned, health plans often have the ability to provide clinical and resource utilization data to physicians that will keep them better informed about their patient's care. New information systems, including computerized medical record and claims systems, can virtually eliminate the barriers between generalists and specialists in keeping track of the clinical care of patients across the entire spectrum of care.

Innovations in the financing of health care by health plans and other managed care organizations can also lead to novel relationships between generalists and specialists that have the potential to improve coordination. One of the more notable examples is the recent experiment with “team contracting” by Oxford Health Care in the New York area.28 In this system Oxford offers a set fee to a team of clinicians for the entire episode of care for patients undergoing particular procedures, e.g., coronary artery bypass surgery. Combinations of generalist and specialist physicians will assume responsibility for the full spectrum of care, and will compete on the basis of outcomes and patient satisfaction for future business from Oxford patients. Oxford and other groups believe that assuming the financial risk as well as the clinical responsibility for these patients will foster new and tightly coordinated generalist–specialist teams.

TEACHING GENERALIST–SPECIALIST PRINCIPLES

There are no published reports of specific educational curricula to teach medical students or residents about the generalist–specialist relationship. Some aspects of the relationship may be incorporated into curricula covering “professionalism” or other similar topics, but physicians in training almost surely learn about this facet of medical practice the way they learn so much else: by watching what their senior physicians do.29 Working with preceptors and other influential figures who model appropriate professional attitudes and behavior is therefore an important place to start in contemplating how to teach this topic. For teachers and learners alike, identifying generalist–specialist relationships as a separate topic for discussion will help signal its importance. Specific principles such as those presented in this article may be useful as background reading, but active learning through role playing, case vignettes, or other standard methods are likely to be most effective for honing personal attitudes and skills. It should also be possible to provide feedback on relationships with referring and consulting physicians as part of assessing resident performance.

Generalist–specialist relationships can be taught solely as a topic of individual duties, attitudes, and skills, but it will be very important to teach how to use “systems” approaches to full advantage. One option would be to have residents form a quality improvement team with the explicit goal of working to improve the systems through which generalists and specialists communicate and share care at their institution. The experience would be made even more meaningful if specialty fellows or staff could be invited successfully to collaborate. Generalists and specialists should both learn, as early as possible, how to express concerns about their mutual relationship, how to understand the views of their colleagues, and how to work with their colleagues as individuals and as interdependent parts of a larger system to improve their relationship.

CONCLUSIONS

Any time a profession undergoes a significant change in its structure or in its position in society, it is a valuable exercise to revisit the core beliefs representing its internal and external value system. This kind of seismic shift in the medical profession happened when hospital-based practice became a major force in England in the early 1800s; it happened when the AMA was founded in this country in the mid-nineteenth century; and it is happening again now.30

The principles presented here are meant to guide behavior in this rapidly changing environment, but are in no way meant to appear inclusive or definitive. They are presented as a starting point, as a spark, for discussions between generalists, specialists, health plans, and the public. What are the elements of generalist–specialist relationships that matter? Which of the features of these relationships that we are accustomed to are worth fighting for in the new order of managed care? What are the new elements of good relationships in managed care systems that we need to focus on and teach to students and residents?

The principles presented here are a first attempt to begin to answer these difficult questions. Discussion of these questions, and of the principles that would address them, should be an integral part of medical school and residency education. In the health care systems of tomorrow, it will continue to be the duty of physicians to understand how to maximize the potential of their working relationships with other physicians to improve the health of their patients.

References

- 1.Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drummond D, Thom B, Brown C, Edwards G, Mullan M. Specialist versus general practitioner treatment of problem drinkers. Lancet. 1990;336:915–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92279-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPhee S, Lo B, Saika G, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1265–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alper PR. Specialists are getting a bum rap. Med Econ. 1996;73:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfield S. Dividing up the turf: generalists versus specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:245–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02642484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel SE. Primary care: specialists or generalists. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:415–9. doi: 10.4065/71.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Zubkoff M, et al. Variations in resource utilization among medical specialties and systems of care: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1992;267:1624–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg JM. Doctor's Decisions and the Cost of Medical Care. Ann Arbor, Mich: Health Administration Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wofford JL, Wilson MC, Moran WP. The promotion of generalism in medicine: Renaissance or recycling? J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:697–701. doi: 10.1007/BF02599014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson EG. When does a generalist need a specialist? J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:247–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02642485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihn SD. Physician specialty, systems of health care, and patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;274:1473–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Percival T. Medical Ethics. Manchester, England: J. Johnson; 1803. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proceedings of the National Medical Convention. 1847. Code of medical ethics; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Physicians Ethics Manual. Ann Intern Med. (3rd ed) 1992;117:947–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-11-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manian FA, Janssen DA. Curbside consultations: a closer look at a common practice. JAMA. 1996;275:145–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummins RO, Smith RW, Inui TS. Communication failure in primary care: failure of consultants to provide follow-up information. JAMA. 1980;243:1650–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee T, Pappius EM, Goldman L. Impact of inter-physician communication on the effectiveness of medical consultations. Am J Med. 1983;74:106–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curry RW, Crandall LA, Coggins WJ. The referral process: a study of one method for improving communication between rural practitioners and consultants. J Fam Pract. 1980;10:287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence R, Dorsey JL. The generalist–specialist relationship and the art of consultation. In: Noble J, editor. Primary Care and the Practice of Medicine. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown & Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams TF, White KL, Fleming WL, Greenberg BA. The referral process in medical care and the university clinic's role. J Med Educ. 1961;36:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Reimbursing physicians and hospitals. JAMA. 1994;272:971–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassirer JP. What role for nurse practitioners in primary care? N Engl J Med. 1994;330:204–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401203300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassirer JP. Access to specialty care. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1151–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311709. Editorial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash DB, Nash IS. Building the best team. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:72–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terry K. Look who's guarding the gate to specialty care. Med Econ. Aug 22, 1994:124–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrov M. Improving the primary care evaluation of infertility. HMO Pract. 1997;11:141–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kertesz L. Organizing specialists: more than 600 physicians have signed up for Oxford “teams” in N.Y.C. area. Mod Health. 1997;27:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds PP. Reaffirming professionalism through the education community. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:609–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-7-199404010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker R, Caplan A, Emanuel LL, Latham SR. Crisis, ethics and the American Medical Association: 1847 and 1997. JAMA. 1997;278:163–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]