Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Because hypoparathyroidism is a serious complication of thyroidectomy, we attempted to elucidate factors determining the risk of this postoperative outcome.

SETTING

Four tertiary care hospitals in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

PATIENTS

A retrospective study of 142 patients who underwent total or subtotal thyroidectomy between 1988 and 1995.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Permanent hypoparathyroidism was defined as hypocalcemic symptoms plus a requirement for oral vitamin D or calcium 6 months after thyroidectomy. Factors analyzed to determine their contribution to the risk of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism were the indication for thyroidectomy, performance of a preoperative thyroid needle biopsy, type of surgery, postoperative pathology, presence and stage of thyroid carcinoma, resident surgeon involvement, and specialty of the surgeon performing the procedure. Surgical specialty and stage of thyroid carcinoma were independent risk factors for persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism by multivariate analysis. Nine (29%) of 31 patients who had thyroidectomy by otolaryngologists met criteria for permanent hypoparathyroidism, and 6 (5%) of 111 patients who had thyroidectomy by general surgeons met the same criteria (p < .001). Adjustment for the effect of stage did not eliminate the effect of specialty (p=.006), and adjustment for the effect of specialty did not eliminate the effect of stage (p=.02), on the occurrence of postoperative hypoparathyroidism.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude from our data that patients undergoing thyroidectomy by an otolaryngologist may be at a higher risk of permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism than patients who undergo thyroidectomy by a general surgeon. This may reflect differences in case selection or surgical approach or both.

Keywords: thyroidectomy, surgical complications, hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, thyroid carcinoma

Chronic hypoparathyroidism is a serious and potentially debilitating disorder that results from a variety of causes. It most commonly occurs as a complication of thyroid surgery, with incidence rates of postthyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism ranging from 0% to 33% depending on the severity of the underlying disease and the extent of the operative procedure.1,2,3,4,1–5Persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism usually results from intentional or inadvertent extirpation of the parathyroid glands during thyroidectomy or from interruption of the blood supply to the glands with subsequent infarction.6Signs and symptoms of the ensuing hypocalcemia include perioral or distal extremity paresthesia, muscle cramping, positive Trousseau and Chvostek signs, laryngeal stridor, and convulsions. The latter conditions may prove fatal. The long-term sequellae of untreated or inadequately treated hypoparathyroidism include premature cataract development, calcification of the basal ganglia, recurrent seizures, osteomalacia, and psychiatric symptomatology.7,8,7–9Clinical management of these patients is costly and can be challenging because the therapeutic window for vitamin D (often a required component of therapy) is narrow. Even short-term vitamin D intoxication, which may be asymptomatic, can cause nephrolithiasis and obstructive uropathy, resulting in permanent kidney damage.6

Laryngeal nerve injury is another potentially serious complication of thyroidectomy. Permanent unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) paralysis manifests clinically as hoarseness, weakness, and breathiness of the voice and occurs with an incidence between 0% and 3.6% after thyroidectomy.3, 10, 11

Traditionally, thyroidectomies have been performed by both general surgeons and otolaryngologists (ear, nose, and throat [ENT] surgeons). Comparison of different medical and surgical specialties with respect to outcome parameters is currently the subject of intensive investigation and is beginning to impact the delivery of health care in the United States.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,1,2,12–23Although such studies are frequently controversial, they have the potential to benefit patients, payers, and physicians alike. Moreover, studies of surgical outcome are of practical concern to primary care providers who may alter their referral patterns on the basis of a proven difference in outcome between two surgical specialties.

Because permanent hypoparathyroidism is a clinically significant complication of thyroidectomy, we attempted to identify those factors that determine the risk of this postoperative complication and other outcome parameters. These retrospective data suggest that the choice of surgical specialty and the stage of thyroid carcinoma are independent risk factors for persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Other factors were considered as potential confounding variables.

METHODS

To assess the rate of development of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism among patients receiving thyroidectomy in a large southwestern community, a retrospective chart review was performed of patients who underwent total or subtotal thyroidectomy between 1988 and 1995 at four tertiary care hospitals in Albuquerque, New Mexico (University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque Veterans Administration Medical Center, Lovelace Medical Center, and Presbyterian Medical Center). This retrospective study received exemption from regulations pertaining to human study by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital. Candidates for study inclusion were identified by querying preexisting databases from each hospital for all thyroidectomies performed during the preceding 6 years. From these, 142 cases of total or subtotal thyroidectomy were identified that included adequate postoperative follow-up data. Data from 438 patients were excluded from analysis for the following reasons: 377 patients received only partial thyroidectomy, 9 patients underwent intentional parathyroidectomy as a component of surgery, 9 patients had incomplete or missing hospital records, and 43 patients' charts lacked adequate postoperative follow-up information.

Data gathered from patient charts included age at time of operation, gender, ethnicity, the indication for thyroidectomy, preoperative and postoperative total serum calcium concentrations, the type of surgery performed (i.e., subtotal, total, or total thyroidectomy with lymph node dissection), the postoperative diagnosis as taken from the postoperative pathology report, and the postoperative clinical status of those patients with carcinoma of the thyroid (i.e., apparent cure, persistent or recurrent disease in the neck or distant metastases). Permanent hypoparathyroidism was defined as the postoperative development of hypocalcemic symptoms plus a requirement for oral vitamin D or supplemental calcium therapy 6 months after surgery. Patients were designated to have transient hypoparathyroidism if symptoms of hypocalcemia developed within the first 2 weeks after thyroidectomy but resolved without the need for specific therapy within 6 months. The presence of postoperative RLN injury was also noted.

Epithelial carcinoma of the thyroid was staged according to the method of Mazzaferri applied to the postoperative pathology report.24Stage I tumors were less than 1.5 cm in diameter or restricted to one lobe of the thyroid and were free of local invasion or distant metastases. Stage II tumors were 1.5 to 4.4 cm in diameter or involved both lobes of the thyroid and were free of local invasion or distant metastases. Stage III tumors were larger than 4.4 cm in diameter or exhibited invasion of local structures in the neck. Stage IV tumors were any tumors that demonstrated distant metastases. Because only one stage IV tumor was identified in this study, stages III and IV were grouped for the purposes of statistical analysis. For analysis of the effect of thyroid cancer staging, all surgeries performed for reasons other than thyroid cancer were assigned a stage of zero.

In an attempt to characterize further factors that may affect the incidence of persistent postthyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism, data for a number of other variables were collected and analyzed. Comparison of the indication for surgery was complicated by the inconsistent performance of preoperative thyroid biopsies in patients with thyroid nodules. Patients who underwent preoperative thyroid biopsy often carried a diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma as the indication for surgery, while those who did not undergo a preoperative thyroid biopsy carried a diagnosis of thyroid nodule or mass as the indication for surgery. For the purposes of analysis, the indications for surgery were based on the preoperative fine needle biopsy, if any, and were grouped as follows: no thyroid carcinoma, thyroid mass without preoperative fine needle biopsy, thyroid mass with indeterminate fine needle biopsy, thyroid mass suspicious for carcinoma by fine needle biopsy, or thyroid carcinoma. In addition, the potential relation of preoperative fine needle biopsy to the development of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism was explored and analyzed. For the analysis of ethnicity as a possible predictive factor for the development of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, patients were grouped as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Caucasian, or other ethnicity. The presence of resident physicians during the operative procedure was also noted. The prospective decision to include subtotal as well as total thyroidectomies in the analysis derives from the fact that persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism has been reported to occur in up to 4% of patients after subtotal thyroidectomy.25

For the purposes of data analysis, postoperative hypoparathyroidism or vocal cord paralysis were treated as outcomes, and other factors (such as postoperative diagnosis) were treated as grouping variables. Univariate analyses were performed using Wilcoxon's Exact Test for variables with ordered categories (such as cancer stage) and Fisher's Exact Test for binary variables. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired Student's t test. Multivariate analysis was performed using stepwise logistic regression to determine relations to independent variables and the effects of confounding variables using SAS software. (PROC GENMOD and the Logistics Procedure, SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements Through Version 6.12, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Results of the univariate analyses are presented first, followed by the multivariate logistic regression and the results of subanalyses and examination of potentially confounding factors. A generalized estimating equation model with Logit link function and the usual compound symmetry correlation structure was employed to assess for the potentially confounding effects of clustering within specific surgeons. Finally, adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are provided for both the full logistic regression (including all variables) and for the best model (including only those factors identified as independent variables).

RESULTS

Study Subjects

Demographic and descriptive characteristics of the 142 qualifying patients who underwent total or subtotal thyroidectomy during the study period are summarized in Table 1

Table 1.

Demographic and Operative Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Total or Subtotal Thyroidectomy in Albuquerque, NM; 1988–1995

Univariate Analyses

The following factors were found to be predictors of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism on the basis of univariate analysis: the presence of thyroid carcinoma (p= .01), stage of thyroid carcinoma (p= .008), and surgical specialty (p < .001). The following factors were not found to be predictive of this postoperative complication: age (p= .95), gender (p= 1.0), ethnicity (p= .09), performance of a preoperative fine needle biopsy of the thyroid (p= .62), indication for thyroidectomy (p= .79), the type of surgery performed (p= .42) , or resident physician involvement in the thyroidectomy (p= .71). Data used for the univariate analyses are shown in Table 2

Table 2.

Data for Univariate Analyses

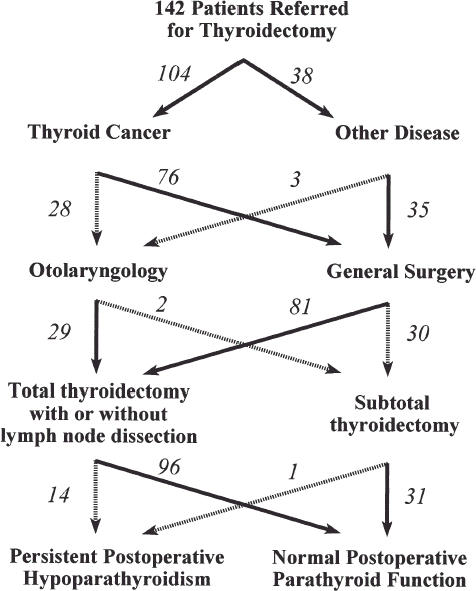

Nine (29%) of 31 patients who had thyroidectomy by an otolaryngologist met criteria for permanent hypoparathyroidism, while 6 (5%) of 111 patients who underwent thyroidectomy performed by a general surgeon met the same criteria (Fig. 1;p < .001). Ten surgeons performed the 31 thyroidectomies in the ENT group, and 7 different surgeons were involved in the 9 cases of permanent hypoparathyroidism observed in this group. In the general surgery group, 27 surgeons performed the 111 thyroidectomies, and 3 surgeons were involved in the 6 cases of permanent hypoparathyroidism observed in this group. One general surgeon was associated with 4 cases of postoperative hypoparathyroidism in a total of 35 thyroidectomies.

Figure 1.

Postoperative parathyroid status according to surgical specialty among 142 patients receiving thyroidectomy in Albuquerque, NM, between 1988 and 1 995. The occurrence of permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism is increased in the ENT group by Fisher's Exact Test.

Multivariate Logistic Regression

Stepwise logistic regression for multivariate analysis identified surgical specialty and stage of thyroid carcinoma as the only independent predictors for the development of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Moreover, the effect of each of these factors persisted when the model was adjusted to account for the other: when adjusted for the effect of thyroid cancer staging, the effect of surgical specialty remained significant (p= .006), and when adjusted for the effect of surgical specialty, the effect of stage also remained significant (p= .02). Results of the multivariate logistic regression are shown in Table 3

Table StepwiseLogistic Regression for Multivariate Analysis of Factors Potentially Related to the Development of Persistent Post-Thyroidectomy Hypoparathyroidism

Subanalyses and Evaluation of Potentially Confounding Factors

Indication for Surgery and Postoperative Diagnosis.

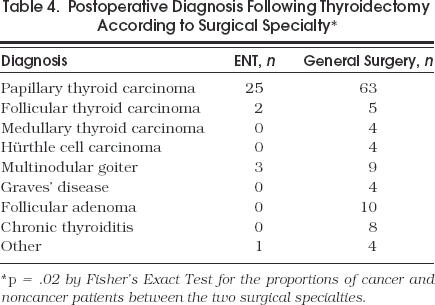

Univariate analysis of the indication for surgery as determined by preoperative thyroid biopsy, if any, revealed a p value of .06 for a difference between surgical groups by Fisher's Exact Test. Analysis of the postoperative diagnosis, as taken from the postoperative pathology report, revealed that 28 (90%) of the 31 patients who received thyroidectomy by an ENT surgeon had a diagnosis of thyroid cancer, compared with 76 (68%) of the 111 patients who received thyroidectomy by a general surgeon (p=.02 by Fisher's Exact Test). Postoperative diagnoses according to surgical specialty are summarized in Table 4 All cases of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism occurred in patients with thyroid cancer in this study.

Table 4.

Postoperative Diagnosis Following Thyroidectomy According to Surgical Specialty

Type of Surgery.

Of the 31 thyroidectomies performed by ENT surgeons, 8 (26%) were performed as total thyroidectomies with neck dissection, 21 (68%) were performed as total thyroidectomies, and 2 (6%) as subtotal thyroidectomies. Of the 111 thyroidectomies performed by general surgeons, 8 (7%) were total thyroidectomies with neck dissection, 73 (66%) were total thyroidectomies, and 30 (27%) were subtotal thyroidectomies. Exact Wilcoxon testing revealed a significant difference in the type of surgery performed between the two surgical groups (p= .002). When subtotal thyroidectomies were removed from the analysis, however, a significant difference persisted for the development of permanent postthyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism between the two surgical groups by Fisher's Exact Test (p < .001).

Staging of Thyroid Carcinoma.

Patients who received thyroidectomy by an ENT surgeon had a more advanced stage of disease than those who received thyroidectomy by a general surgeon by Wilcoxon Exact Test when noncancer patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 2;p= .02). When only patients with thyroid carcinoma were included in the analysis, however, there was no difference between the surgical groups in the stage of thyroid carcinoma (p= .63), and the difference between the surgical groups persisted with respect to the occurrence of permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism (p= .004 by Fisher's Exact Test).

Figure 2.

Distribution of staging of epithelial thyroid carcinoma according to the method of Mazzaferri.24

Clustering of Outcomes Within Specific Surgeons.

Logit analysis using a generalized estimating equation model to assess for the effects of clustering verified the difference in hypoparathyroidism between the two surgical groups (p < .001).

Other Variables.

There was no difference between surgical specialties in the development of transient postoperative hypoparathyroidism by Fisher's Exact Test (p= .50). There were no significant differences between surgical specialties in preoperative or postoperative serum calcium concentrations at 1 to 7 days, 1 month, or 6 months after thyroidectomy by unpaired Student's t test (data not shown, p>.05). Furthermore, Fisher's Exact Test indicated no significant difference between the surgical groups in the performance of a preoperative fine needle thyroid biopsy (p= .62), the involvement of resident physicians in the operative procedure (p= .71), or the postoperative recurrence of thyroid carcinoma among those patients with cancer (p= .81). Laryngeal nerve injury occurred in 2 (6%) of 31 patients in the ENT group and in 2 (2%) of 111 patients in the general surgery group (p= .57). No deaths occurred among patients in this study over the relatively short follow-up period examined.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that thyroidectomy performed by an ENT surgeon (or unidentified associated factors) may carry higher risk of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism than thyroidectomy performed by a general surgeon. This finding is qualified, however, by other factors that may affect this risk and are not uniformly distributed among the study groups. Specifically, a postoperative diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma appears to be a significant predictor of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, and the ENT surgeons predominantly cared for patients with this condition. These data might even be interpreted as suggesting that general surgeons more frequently perform thyroidectomy for indications that are ambiguous or medically uncertain. Moreover, because all of the cases of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism in this study occurred among patients with thyroid cancer, no conclusions can be drawn from these data regarding the risk of this complication following thyroidectomy for nonmalignant indication.

The fact that patients in the ENT group possessed a more advanced stage of disease than patients in the general surgery group further suggests that these patients were at higher risk of postoperative complications before thyroidectomy was even begun. As shown in Table 3, each increase in the stage of thyroid carcinoma was associated with a near doubling of the odds for developing persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. The discrepancy between the surgical groups in the stage of thyroid carcinoma apparent in this study may ultimately reflect an underlying referral bias, with more severely affected subjects being referred to ENT surgeons. Finally, the performance of a more aggressive operative procedure by the ENT surgeons also may have contributed to the difference we observed in our chosen outcome parameter. This practice may be desirable because modified radical neck dissection in addition to thyroidectomy is associated with a decreased rate of tumor recurrence in patients with thyroid carcinoma, although improved survival has not been demonstrated.6,7,8,9,26–30Because the presence of cancer as the indication for thyroidectomy and the performance of more aggressive surgery are both closely related to the stage of the underlying thyroid carcinoma, neither of these factors was identified as an independent variable when adjustment was made for the effect of stage.

Given the variety of factors that appear to contribute to the development of persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, it is unlikely that one factor, such as surgical specialty, will exert a disproportionate influence on this outcome if all other factors are equalized. It may be more accurate to consider a scenario in which a confluence of risk factors determines the ultimate incidence of this postoperative complication. Such a schema is presented in Figure 3, with a postulated high-risk pathway depicted on the left and a low-risk pathway depicted on the right. It seems likely that such a multifactorial scenario most accurately describes the occurrence of postoperative hypoparathyroidism in our study population.

Figure 3.

Postulated chain of events leading to persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Factors on the left are associated with an increased risk of this operative complication. Numbers in italics represent subjects included in the current study.

Similar studies on surgical outcomes have been previously published. Ouriel et al., for example, demonstrated improved postoperative survival when ruptured aortic aneurysm is repaired by a vascular surgeon as compared with a general surgeon among 243 patients and six hospitals in Rochester, New York.21Such studies highlight the existence of differences between and within specialties with respect to medical outcomes, but how such information should be used by the medical community is unclear. Variability between specialties in important outcome measures may be attributable to differences in training, interpretation of the existing literature, patient populations, physician experience, knowledge, skill, or luck. Moreover, it is likely that regional differences in outcome also exist, and these geographic effects may be as (or more) important in determining outcome in any given patient. Thus, studies demonstrating an improved outcome with one specialty relative to another should be interpreted cautiously.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, a reduced power of the study to detect differences as a consequence of the small number of cases of postoperative hypoparathyroidism, the possible restriction of its findings to New Mexico, and the limitations inherent in a retrospective analysis. Also, we were unable to obtain data on the experience of the surgeons performing thyroidectomy in this study. Most experts feel that the experience of the surgeon is one of the most important factors in the avoidance of postoperative complications, and it is conceivable that less experienced physicians were clustered in the ENT group in this study. Furthermore, the validity of our clustering analysis, which was performed as a secondary analysis, may be limited by the small sample size. Nevertheless, because randomized, controlled, prospective studies to determine the optimal surgical management of thyroid disease have not been performed, retrospective studies provide valuable information about current medical practice, cost, and outcome. A preponderance of evidence obtained from such studies may ultimately effect a change in medical practice. Clearly, more definitive studies of the outcome of thyroidectomy are required before such a change can be advocated.

The involvement of resident surgeons during thyroidectomy did not prove to be a significant factor in the development of permanent postthyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism in this study. Similarly, the performance of a preoperative fine needle biopsy of the thyroid did not affect this outcome parameter. Although these findings may reflect a type II statistical error resulting from the small sample size, there is no a priori reason to suspect that either of these factors would play a significant role in the development of postoperative hypoparathyroidism. The lack of difference between the surgical groups in the occurrence of RLN injury may also reflect a type II statistical error, but the rates of RLN injury reported here are consistent with rates reported in other studies.3, 10, 11

We conclude that patients who undergo thyroidectomy by an ENT surgeon may be at an increased risk of developing persistent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Differences in case selection and surgical approach account for some of this disparity, however, and the presence of an advanced stage of thyroid carcinoma is likely to be the most important predictor of this outcome. Referring physicians should be aware of the risk of hypoparathyroidism that accompanies thyroidectomy and discuss this risk with their patients. The risk of permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism may ultimately be reduced by careful communication between the referring physician and the surgeon about the type and extent of surgery perceived to be necessary.

REFLECTIONS

Respite

An intermezzo of silence and solitude: no failing heartbeats or murmurs, no crackles or coughs or shrill alarms, no cries or pleas or questions I cannot answer or comfort I cannot give; no shadows to interpret, tracings to measure, or screens to watch; no grief to witness, suffering to see, pain to touch, or lifeless eyes for me to shut. Out now, of the fluorescent rendering of perpetual day, I stand in the quiet darkness of night, twenty-two stories above the snow-wrapped earth, and watch the city sleeping below, and I listen drowsily to its lullaby.

Garth Meckler, MD

Seattle, Wash.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Robert Ferraro, MD, in assisting the acquisition of data from Presbyterian Medical Center for the purposes of this study.

References

- 1.Sanders L, Rossi R, Cady B. Surgical complications and their management. In: Cady B, Rossi R, editors. Surgery of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands. 3rd. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1991. pp. 326–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahky M, Weber R. Complications of surgery of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73(2):307–21. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45983-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tovi F, Noyek A, Chaonik J, Freeman J. Safety of total thyroidectomy: a review of 100 consecutive cases. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1233–37. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Heerden J, Groh M, Grant C. Early post-operative morbidity after surgical treatment of thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 1987;101:224–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay I, Grant C, Taylor W, McConahey W. Ipsilateral lobectomy versus bilateral lobar resection in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of surgical outcome using a novel prognostic scoring system. Surgery. 1987;102:1088–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster R. Thyroid gland. In: Davis J, Sheldon G, editors. Surgery: A Problem-Solving Approach. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby-Yearbook; 1995. pp. 2185–2247. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonseca O, Calverley J. Neurological manifestations of hypoparathyroidism. Arch Intern Med. 1967;120:202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forman M, Sandler M, Danziger A, Kalk W. Basal ganglia calcifications in postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol. 1980;12:385–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimich A, Bedrossian P, Wallach S. Hypoparathyroidism: clinical observations in 34 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1967;120:449–58. doi: 10.1001/archinte.120.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heraanz-Gonzalez J, Gavilan J, Martinez-Vidal J, et al. Complications following thyroid surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:516–18. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170062014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martensson H, Terins J. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in thyroid gland surgery related to operations and nerves at risk. Arch Surg. 1985;11:475–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390280065014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B, Simpson L. Primary care as part of US health services reform. JAMA. 1993;269:3136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franks P, Nutting PA, Clancy CM. Health care reform, primary care, and the need for research. JAMA. 1993;270:1449–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenfield S, Rogers W, Mangotich M, Carney MF, Tarlov AR. Outcomes of patients with hypertension and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus treated by different systems and specialties: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1995;274:1436–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedmann PD, Brett AS, Mayo-Smith MF. Differences in generalists' and cardiologists' perceptions of cardiovascular risk and the outcome of preventive therapy in cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:414–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguylen HN, Averette HE, Hoskins W, Penalver M, Sevin BU, Steren A. National survey of ovarian carcinoma, part V: the impact of physician's specialty on patients' survival. Cancer. 1993;72:3663–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12<3663::aid-cncr2820721218>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald SE, Voaklander K, Birtwhistle RV. A comparison of family physicians' and obstetricians' intrapartum management of low-risk pregnancies. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick SD, Hornung R, Konrad TR. A comparison of dermatologists and generalists. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1047–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel W, Freund DA, Stein JS, Flechter RH. The treatment of asthma by specialists and generalists. Med Care. 1989;27:306–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horner RD, Matchar DB, Divine GW, Feussner JR. Relationship between physician specialty and the selection and outcome of ischemic stroke patients. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:275–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouriel K, Geary K, Green RM, Fiore W, Deary JE, DeWeese JA. Factors determining survival after ruptured aortic aneurysm: the hospital, the surgeon, and the patient. J Vasc Surg. 1990;11:493–6. doi: 10.1067/mva.1990.18639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKnight JT, Tietze PH, Adock BB, Maxwell AJ, Smith WO, Nagy MC. Screening for prostate cancer: a comparison of urologists and primary care physicians. South Med J. 1996;89:885–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner BJ, Amsel Z, Lustbader E, Schwartz JS, Balshem A, Grisso JA. Breast cancer screening: effect of physician specialty, practice setting year of medical school graduation, sex. Am J Prev Med. 1992;8(2):78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzaferri EL. Carcinoma of follicular epithelium. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. The Thyroid—A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 6th. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott; 1991. pp. 1138–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wingert DJ, Friesen SR, Iliopoulos JI, Pierce GE, Thomas JH, Hemreck JS. Post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia: incidence and risk factors. Am J Surg. 1986;152:606–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark OH. Predictors of thyroid tumor aggressiveness. West J Med. 1996;165:131–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter RV, Frazell EL Foote FW Jr. Elective radical neck dissection: an assessment of its use in the management of papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer. 1970;20:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spires JR, Robbins KT, Luna MA, Byers RM. Metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: the significance of extranodal extension. Head Neck. 1989;11:242–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay ID. Papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1990;19:545–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzaferri EL, Young RL. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: a 10 year follow up report of the impact of therapy in 576 patients. Am J Med. 1981;70:511–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]