Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To develop and validate a prediction rule screening instrument, easily incorporated into the routine hospital admission assessment, that could facilitate discharge planning by identifying patients at the time of admission who are most likely to need postdischarge medical services.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study with separate phases for prediction rule development and validation.

SETTING

Urban teaching hospital.

PATIENTS/PARTICIPANTS

General medical service patients, 381 in the derivation phase and 323 in the validation phase, who provided self-reported medical history, health status, and demographic data as a part of their admission nursing assessment, and were subsequently discharged alive.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Use of postdischarge medical services such as visiting nurse or physical therapy, medical equipment, or placement in a rehabilitation or long-term care facility was determined. A prediction rule based on a patient's age and Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical function and social function scores stratified patients with regard to their risk of using postdischarge medical services. In the validation set, the rate of actual postdischarge medical service use was 15% (15 of 97), 36% (39 of 107), and 58% (57 of 98) among patients characterized by the prediction rule as being at “low”, “intermediate,” and “high” risk of using postdischarge medical services, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

This prediction rule stratified general medical patients with regard to their likelihood of needing discharge planning to arrange for postdischarge medical services. Further research is necessary to determine whether prospective identification of patients likely to need discharge planning will make the hospital discharge planning process more efficient.

Keywords: prediction rule, discharge planning, health status

Efficient discharge planning is becoming an increasingly important component of inpatient hospital care. Financial pressures to shorten length of stay associated with the prospective payment system may result in an increase in the number of elderly patients discharged in unstable condition,1 and in the discharge to home of some patients despite insufficient home care support.2

Although discharge planning 3, 4 and case manage-ment 5–9 services are prevalent, screening methodologies for prospectively identifying which hospitalized patients will need these services remains primitive.10, 11 Factors previously reported to be associated with the need for nursing home placement or other discharge planning services include age, gender, availability of caregivers, and functional status,12 hospital teaching status,13 the number of chronic medical conditions,14 psychiatric comorbidity,11 prior nursing home residence,10, 11, 15 prior home health care use,16 manual ability,17 financial status,18 educational attainment,13 and anticipated discharge to a place other than home.19

Despite research efforts, however, there are currently no screening instruments for discharge planning in common use. This is in part because data collection for existing instruments requires a trained “screener” to perform chart review,8, 11, 15 patient interviews,8, 12, 13 cognitive or physical testing,14 interviews with housestaff or discharge planners,7, 15, 16 or administrative database review.10 In a time of cost reduction, data collection methodologies falling outside routine care undermine the practical utility of previously proposed screening instruments.10, 11, 14, 15, 19–21

A screening instrument administered at the time of admission identifying those patients most likely to need discharge planning services could make discharge planners more efficient by enabling them to target their efforts on the “at-risk” population. To our knowledge, there is no report in the literature of an instrument for predicting the need for discharge planning services derived solely from data collected routinely from patients at the time of hospital admission. Furthermore, there is no report of such a screening instrument being used to improve patient outcomes such as targeting discharge planning services. We therefore developed, and prospectively validated, a screening instrument based on self-reported data collected from patients as a part of routine care, to predict the use of postdischarge medical services (and thus the need for discharge planning) among inpatients on a general medical service.

METHODS

Patients eligible for this study were admitted or transferred to the general medical service of Brigham and Women's Hospital, an urban teaching hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, during two study periods: October 1 through December 23, 1993 (derivation phase) and February 14 through April 8, 1994 (validation phase). General medical service patients at our institution are medical patients who are not admitted to the cardiology service or to the intensive care unit. (Once stabilized, patients from the medical intensive care unit were generally transferred to the general medical service and were then included in our patient population.)

Patient Population

Data were collected as part of routine patient care and through the hospital's quality improvement program under a protocol approved by the institutional review board. All patients admitted to the general medical service were asked to complete the Patient Health History, a questionnaire requesting information about medical conditions, social support, employment status, and health status as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).22 (The SF-36 measures eight components of health status: physical functioning, role–physical, pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, role–emotional, and mental health. Each is represented by a subscale score.) Of the 632 patients admitted to the general medical service during the derivation phase, Patient Health History information was obtained for 387 (61%). These patients were defined as the derivation population. The 245 patients (39%) with no Patient Health History data were excluded from the prediction rule derivation analyses (Table 1) Six (2%) of the 387 patients subsequently died during the hospitalization and were also subsequently excluded from the derivation of the prediction rule because they were never eligible to receive postdischarge medical services. Ultimately, data from 381(60%) of the patients were analyzed to develop the prediction rule.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients Included and Excluded from the Derivation Population and Patients included in the Validation Population

During the validation phase, 327 (55%) of the 597 patients admitted to the general medical service provided Patient Health History information. These patients defined the validation population (Table 1). After excluding the 4 patients (1%) who died in the hospital, data from the remaining 323 (54%) were used to validate the prediction rule. Neither health status nor prediction rule scores were made available to nurses or case managers during either the derivation or validation phase.

Data Collection

Patient Health History questionnaires were given to patients at the time of admission as a part of the routine nursing assessment. If patients were unable to complete the form alone, assistance was provided by the patient's nurse or family member. When the patient was too ill, responses were sought from a family member or other proxy living with the patient. The SF-36 data presented are based on the responses available (i.e., no scores were imputed to replace missing data).

Demographic, clinical, and administrative data were collected from hospital administrative databases. Patients were contacted at 1 month after discharge to determine the use of nonphysician medical services during the 30 days after hospital discharge. So that we might compare the rate of postdischarge medical service use among patients excluded from the prediction rule development with the rate for those included, we attempted to contact all patients discharged alive during the study periods (n= 619 for derivation phase;n= 583 for validation phase).

Follow-up was performed by telephone in the derivation phase, and by mailed questionnaire, followed in 2 weeks by telephone contact, during the validation phase. Telephone interviews were conducted with 467 (75%) of the 619 patients discharged alive from the hospital during the derivation phase or with their proxies. Reasons for noncompletion of follow-up included interview refusal by 10 patients (1.6%), no English-speaking member in the household of 14 patients (2.3%), 19 patient deaths (3.1%), and inability to contact 109 patients (18%). Of the 583 patients discharged alive during the validation phase, we obtained follow-up responses from 400 (69%). Reasons for noncompletion of follow-up included telephone interview refusal by 9 patients (1.5%), no English-speaking member in the household of 16 patients (2.7%), 17 patient deaths (2.9%), and inability to contact 141 patients (24%).

Outcome Measure

Our outcome variable was dichotomous: use (or nonuse) of postdischarge medical services during the 30 days after discharge from the hospital. This included all services requiring discharge planning: placement in nursing, rehabilitation, and mental health facilities; the use of medical equipment at home (such as walkers, hospital beds, or bathroom assistance devices); and home nurse, therapist, or home health aide visits. Office visits with a health care provider, readmission to the hospital, visits to an emergency department, or home visits by a social worker were not included.

As some postdischarge medical services were set up after a patient's discharge, we treated data from the patient or proxy as the primary source for outcome information (available for 75% of the derivation population and for 69% of the validation population) and data from the hospital administrative databases (available for 100% of patients) as the secondary source. (We assumed for the purposes of this analysis that all ordered services were in fact used.)

Analysis

We hypothesized, on the basis of previous research,12 and clinical experience, that health status would be an important predictor of postdischarge medical service use. Patients for whom we had no health status data were therefore not included in the development of the prediction rule. Univariate correlates (p < .05) were determined using the χ2 or Fisher's Exact Test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test for (nonnormal) continuous variables (age and SF-36 scores).

Independent predictors of the outcome variable were identified by forward stepwise logistic regression analysis (and confirmed in a backward regression) using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) where all univariate (p < .05) correlates were entered as independent variables. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived from the regression coefficients and their standard errors.

Development of Prediction Rule

To facilitate the use of this model as a practical prediction rule, we converted continuous independent predictor variables (age, SF-36 physical function, and SF-36 social function) to dichotomous variables, which are more practical to use. The optimal point at which to dichotomize was chosen by running a series of logistic regression analyses to identify the dichotomous variables possessing the most explanatory power. To avoid “overfitting” the prediction rule, p= .01 was chosen as the level of significance for a factor to remain in the model. Finally, we developed a prediction rule scoring system with each dichotomous variable in the final model assigned a point value based on the relative strengths of regression coefficients.

Assessing Model Performance

We used the area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve,23 equal to the c statistic, characterizing the discriminative ability of the prediction rule, to assess model function.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Compared with patients included in the derivation population, patients who were excluded were more likely to be male, single or have an unknown marital status, unemployed or disabled, and nonwhite. These patients also reported fewer comorbid conditions, and were less likely to be divorced or separated, widowed, retired, or have private medical insurance. Despite these demographic differences, hospital mortality, length of stay, and the rates of postdischarge medical service use were similar among patients included and those excluded from the derivation set (Table 1). The most common discharge diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) were also similar among the two populations: of the top 10 DRGs in the derivation population, 7 were also among the top 10 discharge DRGs for the population excluded from the prediction rule development (Table 2).

Table 2.

The 10 Most Prevalent Discharge DRGs Among the Derivation Population and Those Excluded from the Derivation Population

Patients in the derivation and validation populations were generally similar. However, validation population patients had lower mean SF-36 vitality scores and were more likely to be members of an HMO (Table 1). Of the SF-36 subscales, the 387 patients in the derivation population completed the social functioning subscale most frequently (369 patients [95%]) and the general health perception subscale least frequently (336 patients [87%]). Similarly, the 327 validation population patients completed the physical functioning and social functioning subscales most frequently (316 patients each [97%]) and the role–emotional and general health perception subscales least frequently (284 patients each [87%]).

Univariate Analysis

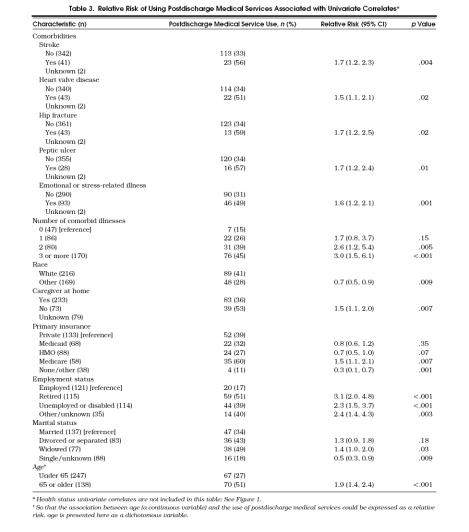

Univariate predictors of postdischarge medical service use are presented in Table 3. Although several clinical conditions (a history of an “emotional or stress-related illness,” stroke, heart valve disease, hip fracture, or peptic ulcer disease) correlated with the use of postdischarge medical services, other past medical conditions, discharge DRG (grouped into the major diagnostic categories 24), patient gender, and admission source (emergent or elective) did not. Patients who used these services also had significantly lower mean SF-36 scores than patients not using services (Table 4).

Table 3.

Relative Risk of Using Postdischarge Medical Services Associated with Univariate Correlates*

Table 4.

Comparison of SF-36 Scores Among Patients Who Used, and Those Who Did Not Use, Postdischarge Medical Services*

Multivariable Analysis

Multivariable analysis identified patient age (odds ratio [OR] 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2, 1.6, for each decade older), SF-36 physical function score (OR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2, 1.4, for each 10-point decrease), and the SF-36 social function score (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1, 1.3, for each 10-point decrease) as independent correlates of postdischarge medical service use (c= 0.80 for this model with three continuous variables). The most powerful model using only dichotomous variables contained the following variables: age 65 or older, SF-36 physical function score of 15 or less, and SF-36 social function score of 50 or less. Based on the strength of the regression coefficients, we generated a prediction rule scoring system: age 65 or older (1 point), SF-36 social function score of 50 or less (1 point), and SF-36 physical function score of 15 or less (2 points). Higher scores indicate greater likelihood of using postdischarge medical services.

Using the observed rates of postdischarge medical service use for derivation population patients within each prediction rule score, patients were grouped into three categories representing risk of using postdischarge medical services: low (score of 0), intermediate (score of 1), and high (score of 2–4). Of the 355 patients from the derivation population with data for each of the prediction rule variables, 93 (26%) were classified as low-risk, 151 (43%) as intermediate-risk, and 111 (31%) as high-risk. Postdischarge medical services were used by 75 (68%), 34 (23%), and 13 (14%) of the patients in the high-, intermediate-, and low-risk categories, respectively (Fig. 1) (c= 0.75 for this final model based on the three risk categories).

Figure 1.

Observed percentage of patients using postdischarge medical services, for derivation and validation population patients in each prediction rule risk category: low = score of 0; intermediate = score of 1 ; high = score of 2–4.

To assess the stability of our model, we performed a second multivariable analysis with use of home nursing services or durable medical equipment as the outcome variable (discharges to a nursing home or rehabilitation hospital were excluded). Exactly the same independent predictors emerged in this model.

Prospective Validation of the Prediction Rule

Of the 323 patients in the validation population, data for each of the prediction rule variables were available for 302 (93%). Ninety-eight (32%) of the validation population patients were categorized as high-risk by the prediction rule, 107 (35%) as intermediate-risk, and 97 (32%) as low-risk. As in the derivation population, the rate of postdischarge medical service use was highest among high-risk validation population patients (57 [58%]), and lower in the intermediate-risk (39 [36%]), and low-risk (15 [15%]) groups (Fig. 1).

The model c statistic, reflecting the discriminative ability of the three-level prediction rule, changed from 0.75 (95% CI 0.70 0.80) in the derivation population to 0.70 (95% CI 0.64 0.76) in the validation population (p= .19). As some general medical service teams had case managers and others did not, we verified that the ROC curves were similar for patients on both types of teams.

DISCUSSION

A screening instrument identifying patients likely to need postdischarge medical services could enhance the efficiency of patient care by targeting discharge planning services to these at-risk patients. To develop such a screening instrument, we determined the predictors of postdischarge medical service use among general medical inpatients. Older age and lower health status, as measured by the SF-36 physical function and social function scores, were independent predictors of a patient's use of postdischarge medical services. A prediction rule screening instrument based on these factors (containing 13 items; taking 2 to 5 minutes to complete) prospectively stratifies patients regarding their likelihood of requiring discharge planning services.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research indicating that placement in long-term care facilities is associated with older age and lower health status.12 Although the absence of a caregiver at home was not an independent risk factor in our multivariate model, the inclusion of the SF-36 social function score (measuring the impact of a patient's physical health or emotional problems on normal social activities) supports the importance of the social environment in predicting the need for home care or nursing home services.25, 26 The wide diversity of DRG in our study, requiring the consolidation of diagnoses into the major diagnostic categories for analysis, undoubtedly diminished the correlation between discharge diagnosis and use of postdischarge medical services. A larger sample size would have been required to determine if individual DRGs correlated with the use of postdischarge medical services.

This study did not attempt to measure all factors previously identified as correlates of postdischarge medical services use, such as attitudes of patients or patients' families regarding institutionalization or economic status,11 or prior medical resource utilization.14 However, these data were not routinely available for this patient population, whereas all data in this decision rule were collected as a part of routine care. Further research is required to determine if data regarding the previous use of home medical services and the type of residence before admission (information that could be routinely collected form patients) would enhance the power of this prediction rule.

Only general medical patients from one urban teaching institution, where the overall rate of postdischarge service use was high, were evaluated in this study; hence, even though the prediction rule stratified patients well according to their use of postdischarge services, 15% of patients in the low-risk group received these services. Furthermore, our mortality rate was relatively low (2% overall); in institutions with higher rates, the utility of the rule as an instrument to target discharge planners could be diminished.

One of the potential strengths of this prediction rule is that data collection can be incorporated into the routine nursing admission assessment. Nevertheless, the generalizability of our study is limited because only 61% of the eligible patients in the development phase and 55% of the eligible patients in the validation phase completed essential information on the SF-36. Our anecdotal experience indicates that acute illness, language barriers, as well as nursing and patient unfamiliarity with health status questions were factors leading to the incomplete collection of Patient Health History data. In the future we plan to limit the collection of health status data to the 13 prediction rule questions to simplify the screening process.

This screening instrument stratifies patients, at admission, regarding their likelihood of requiring postdischarge medical services. Because of the limited sample size, the confidence intervals around the prediction rule ROC area were wide in both development and validation. Further study is required to validate these findings and to determine if a discharge planning intervention targeted to those patients most likely to need discharge planning services can enhance the efficiency of the hospital discharge planning process.

References

- 1.Rogers WH, Draper D, Kahn KL, et al. Quality of care before and after implementation of the DRG-based prospective payment system. A summary of effects. JAMA. 1990;264:1989–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolock I, Schlesinger E, Dinerman M, Seaton R. The posthospital needs and care of patients: implications for discharge planning. Soc Work Health Care. 1987;12:61–76. doi: 10.1300/J010v12n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:999–1006. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moher D, Weinberg A, Hanlon R, Runnalls K. Effects of a medical team coordinator on length of hospital stay. Can Med Assoc J. 1992;146(4):511–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams FG, Warrick LH, Christianson JB, Netting FE. Critical factors for successful hospital-based case management. Health Care Manage Rev. 1993;18(1):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald JF, Smith DM, Martin DK, Freedman JA, Katz BP. A case manager intervention to reduce readmissions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1721–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick WC, Inui TS, Deyo RA, Wood RW. The central role of case managers in early discharge planning for hospitalized persons with AIDS. J Case Manage. 1994;3(2):56–61, 87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuben DB, Borok GM, Wolde-Tsadik G, et al. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the care of hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1345–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass RI, Weiner MS. Seeking a social disposition for the medical patient: CAAST, a simple and objective clinical index. Med Care. 1976;14:637–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inui TS, Stevenson KM, Plorde D, Murphy I. Identifying hospital patients who need early discharge planning for special dispositions: a comparison of alternative techniques. Med Care. 1981;19:922–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingard DL, Jones DW, Kaplan RM. Institutional care utilization by the elderly: a critical review. Gerontologist. 1987;27:156–63. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane RL, Matthias R, Sampson S. The risk of placement in a nursing home after acute hospitalization. Med Care. 1983;21:1055–61. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans RL, Hendricks RD, Lawrence KV, Bishop DS. Identifying factors associated with health care use: a hospital-based risk screening index. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:947–54. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachtel TJ, Fulton JP, Goldfarb J. Early prediction of discharge disposition after hospitalization. Gerontologist. 1987;27:98–103. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soloman DH, Wagner DR, Marenberg ME, Acampora D, Cooney LM, Inouye SK. Predictors of formal home health care use in elderly patients after hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:961–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams ME, Hornberger JC. A quantitative method of identifying older persons at risk for increasing long term care services. J Chron Dis. 1984;37:705–11. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrow-Howell N, Proctor E. Discharge destinations of Medicare patients receiving discharge planning: who goes where? Med Care. 1994;32:486–97. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glass RI, Mulvihill MN, Smith H, Peto R, Bucheister D, Stoll BJ. The 4 score: an index for predicting a patient's non-medical hospital days. Am J Public Health. 1977;67:751–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.8.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reuben DB, Wolde-Tsadik G, Pardamean B, et al. The use of targeting criteria in hospitalized HMO patients: results from the demonstration phase of the Hospitalized Older Persons Evaluation (HOPE) study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:482–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winograd CH. Targeting strategies: an overview of criteria and outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39S:25–35S. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb05930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Surey (SF-36): psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein MC, Fineberg HV. Clinical Decision Analysis. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The DRG Handbook: Comparative Clinical and Financial Standards. Baltimore, Md: HCIA, Inc. and Ernst & Young LLP; 1995. 535–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branch LG, Jette AM. A prospective study of long-term care institutionalization among the aged. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1373–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.12.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCoy JL, Edwards BE. Contextual and sociodemographic antecedents of institutionalization among aged welfare recipients. Med Care. 1981;19(9):907–21. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]