Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine if hypothesized differences in attitudes and beliefs about cigarette smoking between Latino and non-Latino white smokers are independent of years of formal education and number of cigarettes smoked per day.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional survey using a random digit dial telephone method.

SETTING

San Francisco census tracts with at least 10% Latinos in the 1990 Census.

PARTICIPANTS

Three hundred twelve Latinos (198 men and 114 women) and 354 non-Latino whites (186 men and 168 women), 18 to 65 years of age, who were current cigarette smokers participated.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

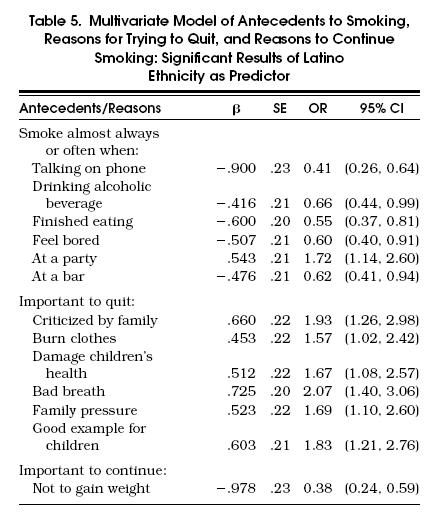

Self-reports of cigarette smoking behavior, antecedents to smoking, reasons to quit smoking, and reasons to continue smoking were the measures. Latino smokers were younger (36.6 vs 39.6 years, p < .01), had fewer years of education (11.0 vs 14.3 years, p < .001), and smoked on average fewer cigarettes per day (9.7 vs 20.1, p < .001). Compared with whites, Latino smokers were less likely to report smoking “almost always or often” after 13 of 17 antecedents (each p < .001), and more likely to consider it important to quit for 12 of 15 reasons (each p < .001). In multivariate analyses after adjusting for gender, age, education, income, and number of cigarettes smoked per day, Latino ethnicity was a significant predictor of being less likely to smoke while talking on the telephone (odds ratio [OR] 0.41; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.26, 0.64), drinking alcoholic beverages (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.44, 0.99), after eating (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.37, 0.81), or at a bar (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.41, 0.94), and a significant predictor of being more likely to smoke at a party (OR 1.72; 95% CI 1.14, 2.60). Latino ethnicity was a significant predictor of considering quitting important because of being criticized by family (OR 1.93; 95% CI 1.26, 2.98), burning clothes (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.02, 2.42), damaging children's health (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.08, 2.57), bad breath (OR 2.07; 95% CI 1.40, 3.06), family pressure (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.10, 2.60), and being a good example to children (OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.21, 2.76).

CONCLUSIONS

Differences in attitudes and beliefs about cigarette smoking between Latinos and whites are independent of education and number of cigarettes smoked. We recommend that these ethnic differences be incorporated into smoking cessation interventions for Latino smokers.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, Latinos, Hispanics, culture

Increasing ethnic diversity in the United States mandates the development of culturally appropriate health-related interventions supported by background research.1 To develop interventions applicable at the community level or in clinical circumstances, similarities and differences in attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to the outcomes of interest must be evaluated in the target population. Health care researchers and policy makers should not assume that an intervention program effective with non-Latino whites (henceforth whites) will have similar results in other ethnic groups.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States among all ethnic groups.2 Most cigarette smokers who successfully quit do so on their own, motivated by a variety of psychological, social, and health-related reasons.3 Policies regulating smoking, media campaigns against smoking, well-designed self-help cessation materials, and advice from clinicians are potential elements of a public health strategy to promote nonsmoking.4 Given the substantial differences in sociocultural background among ethnic groups in the United States, it is reasonable to postulate that ethnic differences in cigarette smoking behavior, attitudes, and beliefs should influence the content of smoking cessation interventions.

National and regional surveys have found that, on average, fewer Latinos smoke than whites, and among current smokers Latinos average fewer cigarettes per day.5–8 Our previous work with convenience samples showed that compared with whites, Latinos are less likely to smoke in response to habitual cues, as likely to smoke in response to emotional cues, and more likely to want to quit because of cigarette smoke's effects on others' health, interpersonal relationships, and their own health. 9–14

Whether these differences in attitudes, beliefs, and behavior are related to ethnicity or are confounded by differences in education and level of nicotine dependence remains unclear. Level of formal education is likely to influence culturally driven beliefs and attitudes, and more important, affect knowledge and access to information regarding the effects of smoking and reasons to quit. Because of the differences in level of nicotine dependence, it is plausible to postulate that the “attitude” or “belief” Latinos may hold about quitting smoking or continuing to smoke is in part driven by less-intense addiction. Less-dependent smokers are more likely to find it easier to quit under any circumstances; thus, they are also more likely to agree that it is important to quit for any reason offered and less important to continue smoking for any reason offered, and to cite fewer antecedents to smoking. In order to address the contribution of education, nicotine dependence, and ethnicity to attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs about cigarette smoking, we conducted a population-based survey of Latino and white smokers in San Francisco to evaluate differences and similarities in antecedents to cigarette smoking, reasons for trying to quit smoking, and reasons to continue smoking.

METHODS

Sampling and Procedure

Participants were sampled from the 52 census tracts in San Francisco County in which at least 10% of the population was reported to be Hispanic (Latino) in the 1980 U.S. Census.15 This sampling universe represented 89% of the 66,084 Latinos and 33% of the 285,576 non-Latino whites, between 18 and 65 years of age, living in San Francisco in 1990.16 Telephone prefixes corresponding to the census tracts were identified using a reverse telephone directory. We applied a modified Mitofsky-Waksberg 17 method for random digit dialing that we have successfully used in other surveys to identify eligible respondents.18

A household was considered to be eligible if the person answering the telephone self-identified as Latino/Hispanic or non-Latino Caucasian/white or Anglo on screening questions. Within a given household, the adult between 18 and 65 years of age who had most recently celebrated a birthday was invited to respond to the survey. Households with a respondent who reported current cigarette smoking were administered a longer set of questions on cigarette smoking. Potential respondents were not replaced within a household. Respondents who classified themselves as Latino, but who were subsequently found not to be Latino by their responses on family background were excluded from the study (n= 8).

The telephone survey was conducted anonymously in the summer of 1990 by trained, supervised, and experienced bilingual and bicultural interviewers of both genders after subjects gave verbal consent in either English or Spanish. Subjects who actively refused initially were called a second time, and unavailable eligible respondents were called approximately 10 times before they were assumed to have refused. The survey instrument and a more detailed description of the interview procedure are available from the authors on request.

Questionnaire

Demographic variables measured included gender, age, education, employment in previous 2 weeks, birthplace, household income, and national background (only among persons born in the United States). Latinos completed a 5-item acculturation scale, and scores were dichotomized into groups that are less acculturated (1 to <3) and more acculturated (≥3 to 5).19 Smoking behavior items included the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the age the subject started smoking, and smoking status a year before the survey. The level of nicotine dependence was defined by the number of cigarettes smoked per day.

Questionnaire items were derived from data collected during open-ended individual interviews with Latino and white smokers, never smokers, and former smokers. A structured, hour-long questionnaire was developed, extensively pretested, and administered face-to-face with convenience samples of Latino and white smokers. Questionnaire items for this study were selected from previously completed studies, adapted for telephone administration, and pretested. The items were selected as the most likely to provide useful information in evaluating ethnic differences about cigarette smoking.

Questions on 17 antecedents to cigarette smoking asked participants whether they smoked almost always, often, almost never, or never, when doing habitual activities (talking on the telephone, watching television, finished eating, drinking coffee, drinking alcoholic beverages), in social settings (at a party, with friends, with other smokers, at a bar), in relation to emotional states (worried, nervous or tense, feel happy, upset or angry), or in other mental situations (concentrating, feel tired, feel bored, relaxing). Fifteen reasons for trying to quit smoking were presented, and respondents were asked to categorize these as important or not important reasons to quit. Reasons to quit smoking were grouped as those that were related to familialismo(criticized by family, damaging others' health, damaging children's health, effect on others, family pressure, good example for children), to smokers' own health (breathe better, future health, damage own health, achieve difficult goal), to simpatía, affected by smokers' appearance (burning clothes, smell in hair or clothes, bad breath, get more wrinkles), and to cost. Finally, participants were asked to classify as important or not important three reasons to continue smoking—not to gain weight, to feel less nervous, and to help with concentration.

Face validity of the questionnaire items was determined by review of extensive open-ended interviews conducted face-to-face with Latino and white current, former, and never smokers. Similar items used in previous interviews showed excellent reliability.

Data Analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed using standard techniques, and means and standard deviations were computed where appropriate using SPSSX (Users Guide. 2nd ed. Chicago, Ill: SPSS, 1986). Proportions were compared by corrected χ2 tests, and continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance techniques. Because they were multiple comparisons, we set the significance level at p < .001. We calculated the differences and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of this difference (Latinos minus whites), in the proportion of Latinos and whites who reported smoking almost always or often for each of the 17 antecedents, that it was important to quit for each of the 15 reasons asked, and that it was important to continue smoking for the 3 reasons asked.20 We provided the CIs as a basis for evaluating the magnitude of the differences between Latinos and whites even if these were not statistically significant.21 Ethnic differences (white as referent) in the results (17 antecedents, 18 reasons to quit or continue smoking) were evaluated using logistic regression analyses adjusted for gender (women), age (continuous), education (continuous), employment (yes), income (categories), and cigarettes per day (continuous). Further multivariate analyses of the Latino sample were adjusted for acculturation level (continuous) and national origin (categories).

RESULTS

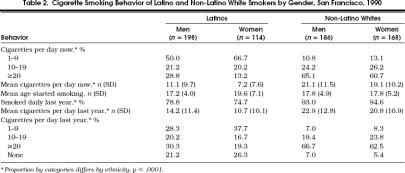

A total of 666 current cigarette smokers completed the survey: 312 Latinos (198 men and 114 women) and 354 whites (186 men and 168 women). Of the 830 potentially eligible participants contacted, 6% actively refused and 14% were unavailable, representing a collaboration rate of approximately 80%. There were no differences in collaboration by ethnicity. The age-adjusted rate of current smokers among Latinos was 23.3% among men and 12.2% among women and was higher among the more-acculturated (19.5%) than among the less-acculturated Latinos (14.2%).22 Although we did not interview nonsmoking whites to ascertain smoking rates in 1990, age-adjusted rates in 1989 were 29.6% for men and 29.2% for women. Comparison of demographic variables (Table 1) by ethnicity showed that a greater proportion of the Latinos were men (63.5% vs 52.5%), and that Latino smokers were younger (mean [SD], 36.6 [11.7] vs 39.6 [13.3] years;t= 3.05, df= 663, p < .01), had fewer years of education (11.0 [4.3] vs 14.3 [2.2] years;t= 11.99, df= 470, p < .0001), and were more likely to report a household income of less than $20,000 per year (55% vs 26.9%;χ2= 45, df = 1, p < .0001). The proportion of Latino smokers with less than a high school education was nearly eight times that of whites (χ2= 119, df= 1, p < .0001). The percentage of respondents employed did not differ by ethnicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Latino and Non-Latino White Cigarette Smokers, San Francisco, 1990

A majority of Latino respondents preferred to answer the survey in Spanish (74.4%), and 71% were born in Latin America (Mexico 27% and Central America 33%). The mean (SD) duration of time living in the United States for foreign-born Latinos was 14 (10.6) years. Among all Latinos, 38.8% were of Mexican background, 39.7% were of Central American background, and 21.8% were of other Latin American background. Mean (SD) acculturation score for the sample was 2.7 (1.3), with 57.7% scoring as less acculturated (1 to <3).

Smoking Behavior

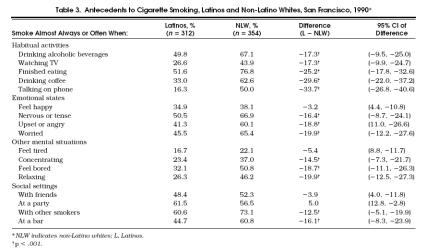

Cigarette smoking behavior differed by ethnicity and gender (Table 2 Compared with whites, Latinos smoked fewer cigarettes per day (9.7 vs 20.1;t= −13.4, df= 662, p < .0001), with 56% of Latinos reporting 1 to 9 cigarettes per day compared with only 12% of non-Latino whites (χ2= 147, df= 1, p < .0001). Overall ethnic differences were also reported for smoking behavior a year before the survey, but not for the age subjects started smoking. Differences by ethnicity in number of cigarettes smoked per day were present for men (11.1 vs 21.1 cigarettes;t= −9.2, df= 362, p < .001) and women (7.2 vs 19.1;t= −11.2, df= 277, p < .001). Although all smokers tended to report smoking more cigarettes per day a year before the survey, 23.1% of current Latino smokers claimed to not be smoking at all 1 year before compared with 6.2% of whites.

Table 2.

Cigarette Smoking Behavior of Latino and Non-Latino White Smokers by Gender, San Francisco, 1990

Antecedents to Cigarette Smoking

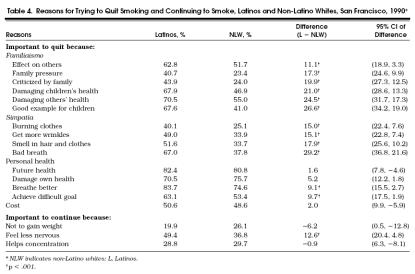

Table 3 compares antecedents to cigarette smoking among smokers by ethnicity. Latinos reported being less likely to smoke almost always or often for 13 of the 17 antecedents presented. Of the four antecedents not found to be significantly different, two were related to social smoking (at a party or with friends) and two to feeling states (happy or tired). The greatest differences were for smoking after habitual activities and specifically while talking on the telephone, after drinking coffee, and when finished eating. Five antecedents to cigarette smoking were reported by half or more of the Latino smokers, and these were while being at a party, when with other smokers, after eating, while nervous or tense, and when drinking alcoholic beverages. At least half of the white smokers reported being likely to smoke after 12 of the 17 antecedents, and the most frequent were after eating, when with other smokers, while drinking alcoholic beverages, while nervous or tense, and when worried.

Table 3.

Antecedents to Cigarette Smoking, Latinos and Non-Latino Whites, San Francisco, 1990*

Reasons for Trying to Quit or Continuing to Smoke

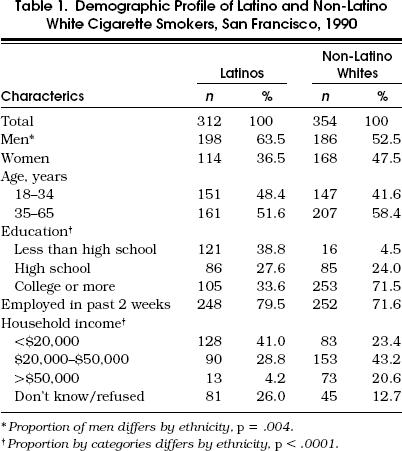

Ethnic differences in the reasons considered important for trying to quit smoking and for continuing to smoke are shown in Table 4. Latinos were more likely to report that 12 of 15 reasons to quit were “important.” Costs of cigarettes, future personal health, and damage to one's health were not reasons to quit that differed by ethnicity in the percentage of respondents considering them important. The largest differences were noted for having bad breath, setting a good example for children, damaging others' health, and damaging children's health. The most frequently reported reasons considered important to quit by Latino smokers were breathing better, future health, damaging others' health, damaging own health, damaging children's health, setting a good example for children, and having bad breath. Among whites the most frequently reported reasons considered important to quit were future personal health, damaging own health, breathing better, damaging other's health, and achieving a difficult goal. Among the three reasons for why it is important to continue smoking, a greater proportion of Latinos than non-Latino whites reported feeling less nervous as important.

Table 4.

Reasons for Trying to Quit Smoking and Continuing to Smoke, Latinos and Non-Latino Whites, San Francisco, 1990*

Multivariate Analyses

The results of multivariate logistic regression models to ascertain the effect of Latino ethnicity on antecedents to smoking and reasons to quit or continue smoking are shown in Table 5. After adjusting for gender, age, education, income, and number of cigarettes smoked per day, significant differences by ethnicity were observed in six antecedents and seven reasons to quit or continue smoking. Latinos were less likely to smoke cigarettes when talking on the telephone, drinking alcoholic beverages, finished eating, feeling bored, or at a bar and more likely to smoke while at a party. Latinos were significantly more likely to report that it was important to quit because of criticism by family, family pressure, damaging children's health, setting a good example for their children, burning clothes, and having bad breath. Latinos were also less likely to believe that not gaining weight was an important reason to continue smoking.

Table 5.

Multivariate Model of Antecedents to Smoking, Reasons for Trying to Quit, and Reasons to Continue Smoking: Significant Results of Latino Ethnicity as Predictor

Other predictor variables were significantly associated with smoking antecedents and reasons to quit or continue smoking with odds ratios (ORs) that were significant at p < .001. Smokers who smoked more cigarettes per day were more likely to report smoking almost always or often with 15 of the 17 antecedents (only drinking alcoholic beverages and being at a bar were not significant) and less likely to consider bad breath as an important reason to quit. Older persons were less likely to report smoking when drinking alcoholic beverages or when nervous or tense, and less likely to consider damaging children's health, smell in hair or clothes, effect of smoking on others, and setting a good example for children as important reasons to quit smoking. Men were less likely to smoke when talking on the telephone or when upset or tired, more likely to smoke when at a bar, and less likely to consider getting more wrinkles as a reason to quit smoking. Years of education was not a significant predictor for any of the antecedents to smoking, but persons with fewer years of education were less likely to consider criticism by family, burning one's clothes, damaging children's health, getting more wrinkles, family pressure, or setting a good example for one's children as important reasons to quit smoking.

Effect of Language, Acculturation, and National Origin Among Latinos

Among the Latino sample only, we examined the effect of language of response to interview on the antecedents and reasons for trying to quit or continuing to smoke. Latinos who responded to the survey in Spanish were less likely to smoke when talking on the telephone (12% vs 29%;χ2= 12.1, df= 1, p < .01) and relaxing (22% vs 38%;χ2= 7, df= 1, p < .01) and more likely to smoke when feeling tired (20% vs 6%;χ2= 8.48, df= 1, p < .01). Spanish-speaking Latinos were more likely to report having bad breath (73% vs 51%;χ2= 12.39, df= 1, p < .01), getting more wrinkles (54% vs 36%;χ2= 7.38, df= 1, p < .01), and breathing better (88% vs 71%;χ2= 12.35, df= 1, p < .01) as important reasons to quit smoking.

Multivariate models controlling for gender, age, education, and number of cigarettes per day were constructed to evaluate the effect of acculturation and national origin on antecedents to smoking and reasons to quit smoking. Acculturation score and language response to interview are highly correlated, but we selected acculturation because it is a continuous predictor variable. For each unit increase in acculturation score, Latinos were more likely to smoke when drinking alcoholic beverages (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.15, 1.83), and for each unit decrease, they were less likely to smoke when feeling tired (OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.52, 0.94). None of the other 15 antecedents was significantly related to acculturation. For each unit increase in acculturation score, Latinos were less likely to consider it important to quit because of damaging their children's health (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.59, 0.94), damaging others' health (OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.60, 0.95), and breathing better (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54, 0.94). Having bad breath (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62, 0.98), getting more wrinkles (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.65, 1.0), and burning clothes (OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.65, 1.0) approached statistical significance by acculturation. There were not statistically significant differences by the three national origin groups of Latinos (Mexican, Central American, other) in any of the antecedents, reasons to quit, or reasons to continue smoking.

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies comparing attitudes, beliefs, and behavior about smoking and quitting in a convenience sample of Latino and white smokers found significant ethnic differences in smoking behavior, antecedents to cigarette smoking, and reasons why it is important to quit smoking.10–12 Several regional and national population-based surveys subsequently confirmed that compared with whites, Latino smokers average fewer cigarettes per day, have lower average serum cotinine levels, and report less addiction to cigarettes.23–26 Differences in beliefs about cigarette smoking between Latino and white smokers and by language preference were also reported in a large population-based sample in California.23 Our study is the first to examine smoking antecedents, reasons to quit smoking, and reasons to continue smoking in a population-based sample of Latino and white smokers. Our findings support the presumption of ethnic-specific attitudes and beliefs about cigarette smoking among Latino smokers. These observations need to be considered and integrated in the development and implementation of smoking cessation interventions for Latino adults in both public health programs and office-based counseling.27

Previous analyses of the attitudes and beliefs about smoking in a convenience sample showed that, compared with white smokers, Latino smokers perceived their smoking to be less dependent on habitual activities and equally dependent on social and emotional cues despite a lower level of dependence.10–12 Latinos were also more concerned about the effects of smoking on interpersonal relationships, especially within the family, had a heightened concern about the consequence of harming the health of their children by continuing to smoke, and were more likely to cite giving a better example to their children and improving relations within the family as reasons to quit smoking.10–12 However, these data were not based on a population-based sample and were subjected to limited multivariate adjustments.

The findings from the current study confirm the general themes derived from the earlier studies. After adjusting for age, gender, education, income, and number of cigarettes smoked per day, six smoking antecedents, six reasons to quit smoking, and one reason to continue smoking were significantly different between Latinos and whites. Four situational cues and one emotional state were associated with Latinos being less likely to smoke, and one social setting was associated with Latinos being more likely to smoke. Latinos were more likely to cite reasons as important to quit smoking that reflected concerns about family and interpersonal relationships. The importance of the family and collective well-being, represented by the cultural dimension of famialismo,28 has also been found in a study of smokers in a medical setting.29 The Latino cultural script of simpatía is also consistent with these findings that minimizing interpersonal conflict is an important reason for Latinos to quit smoking.30 Finally, the relative importance of remaining thin was diminished among Latino smokers as a reason to continue smoking. Other data indicate that Latinos are less concerned with the cultural ideal of thinness of U.S. society, and this is borne out by the prevalence of obesity among Latino women.31, 32

Palinkas and colleagues reported results from the California tobacco surveys comparing beliefs about cigarette smoking among 8,118 non-Hispanic white, 655 English-speaking, and 507 Spanish-speaking Hispanics.23 The 15 beliefs presented were different from the questions we asked and did not include any smoking antecedents. However, in univariate analyses, Spanish-speaking Hispanics appeared more likely than non-Hispanic whites to believe that tobacco was not addicting, that living longer was a reason not to smoke, that smoking during pregnancy harms the baby, and that smoking is something the majority should try once.23 Although language and acculturation may explain some of the observed ethnic differences, these are not the only factors affecting beliefs and attitudes about cigarette smoking.

The observations of ethnic differences and similarities in attitudes and beliefs about smoking need to be considered in the development of cessation and prevention in interventions.27 For example, a public health media program on cigarette smoking cessation should emphasize quitting for the sake of the family's health and decrease the emphasis on quitting to improve personal health. The relative importance of maintaining a better personal appearance as motivation to quit smoking is highlighted by our results and would need to be a focus of a cessation campaign. Our program implemented in San Francisco and the California media campaign against tobacco use directed at Latinos indicate that these themes can be effectively integrated into community campaigns.33–35

Primary care physicians have a central role in counseling smokers to quit, and the contrasting attitudes and beliefs from this study lead to modification of established strategies in counseling Latino patients. For example, in boosting motivation to quit, physicians need to discuss maintenance of family's health and personal appearance, as opposed to personal health or getting rid of an addiction. In anticipating relapse situations, Latino smokers trying to quit should be especially cautioned about social situations, with less concern raised because of habitual cues.

This study has several important limitations. First, all responses were by self-report and validation of smoking behavior or reasons to quit or continue smoking was not possible with a cross-sectional design. A cohort study is necessary to further confirm these findings. Second, these data may not be generalizable to Latinos from other national backgrounds, specifically Puerto Ricans and Cubans who are heavier smokers.5 The fact that we adjusted for number of cigarettes smoked per day and found ethnic-specific differences would support a Latino cultural theme independent of national background. Third, several of the responses to smoking antecedents and reasons to quit smoking questions may be related to independent variables that remained unadjusted and could be addressed in future studies. For example, some Latinos may be less likely to smoke when drinking alcoholic beverages because they drink less at a given time. Similarly, Latinos may give greater importance to the effects of smoking on family and children because they have larger families. Fourth, we did not ask smokers about past quit attempts and their reasons that were important to attempt to quit and continue smoking. However, it seems unlikely that these ethnic differences are a consequence of past quit attempt experiences given the similarity of quitting behavior by ethnicity.26 Finally, our sample size limited subgroup analyses, and important differences by acculturation among Latinos may be found in a larger study.

Despite these limitations, our study provides evidence that attitudes and beliefs of cigarette smoking differ between Latinos and non-Latino whites. Unlike previous studies, our study's data are based on a population-based sample and adjusted for demographic factors that are known to affect smoking. Furthermore, the observed differences are not entirely accounted for by level of nicotine dependence as measured by number of cigarettes per day. These findings need to be considered in development and implementation of cigarette smoking cessation with Latinos, and we recommend that similar studies be conducted with other ethnic groups in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Public Health Service grant CA39260 awarded by the National Cancer Institute and by grant HS07373-01 from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Dr. Pérez-Stable was a Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Faculty Scholar in general internal medicine.

The authors thank Barbara VanOss Marín for contributions in the development of the questionnaire, Rosa Marcano for supervising the interviewers for the survey, Sylvia Correro for overall administration coordination, and Celina Echazarreta for research assistance.

References

- 1.Marín G. Defining culturally appropriate community interventions: Hispanics as a case study. J Comm Psychol. 1993;21:149–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desenclos JCA, Hahn RA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Years of potential life lost before age 65, by race Hispanic origin, and sex—United States, 1986–1988. MMWR. 1992;41(SS-6):13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, et al. Methods used to quit smoking in the United States: do cessation programs help? JAMA. 1990;263(20):2760–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Strategies to Control Tobacco Use in the United States: A Blueprint for Public Health Action in the 1990's. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1991. NIH publication 92-3316. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes SG, Harvey C, Montes H, Nickens H, Cohen BH. VIII. Patterns of cigarette smoking among Hispanics in the United States: Results from HHANES 1982–1984. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(suppl):47–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus AC, Crane LA. Smoking behavior among US Latinos: an emerging challenge for public health. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:169–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marín G, Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín BV. Cigarette smoking among San Francisco Hispanics: the role of acculturation and gender. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:196–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín G, Marín BV. Behavioral risk factors among Latinos compared to non-Latino whites in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:971–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marín G, Marín BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F, Pérez-Stable EJ. The role of acculturation on the attitudes, norms, and expectancies of Hispanic smokers. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1989;20(4):399–415. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marín G, Pérez-Stable EJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F, Marín BV. Stereotypes of smokers held by Hispanic and white non-Hispanic smokers. Int J Addict. 1989;24:203–13. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marín BV, Marín G, Pérez-Stable EJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F. Cultural differences in attitudes toward smoking: developing messages using the theory of reasoned action. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1990;20:478–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marín G, Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Sabogal F. Cultural differences among Hispanics and non-Hispanic white smokers: attitudes and expectancies. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1990;12(4):422–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín G, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R. Attitudes and behaviors of Hispanic smokers: implications for cessation interventions. Health Educ Q. 1990;17(3):287–97. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R, Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín BV, Marín G. Perceived self-efficacy to avoid cigarette smoking and addiction: differences between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1989;11(2):136–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bureau of the Census Department of Commerce . 1980 Census of Population: Age, Sex, Race, and Spanish Origin of the Population by Regions, Divisions and States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1983. PC80-S1-1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau of the Census, Economics and Statistics Administration . Race and Hispanic Origin: 1990 Census Data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waksberg J. Sampling methods for random digit dialing. J Am Statist Assoc. 1978;73:40–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marín G, Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ. Feasibility of a telephone survey to study a minority community: Hispanics in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:323–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marín G, Sabogal F, Marín BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Pérez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott L. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis. Boston, Mass: PWS-Kent Publishing Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon R. Confidence intervals for reporting results of clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:429–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-3-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marín G, Pérez-Stable EJ. Effectiveness of disseminating culturally appropriate smoking-cessation information: Programa Latino Para Dejar de Fumar. Monogr J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;18:155–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palinkas LA, Pierce J, Rosbrook BP, Pickwell S, Johnson M, Bal DG. Cigarette smoking behavior and beliefs of Hispanics in California. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(6):331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1993. MMWR. 1994;43(50):925–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín G, Marín BV, Benowitz NL. Misclassification of smoking status by self-reported cigarette consumption. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:53–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkleby MA, Schooler C, Kraemer HC, Lin J, Fortmann SP. Hispanic versus white smoking patterns by sex and level of education. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:410–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín BV, Marín G. A comprehensive smoking cessation program for the San Francisco Bay Area Latino community: Program Latino Para Dejar de Fumar. Am J Health Promot. 1993;7(6):430–42,475. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-7.6.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: what changes and what doesn't? Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(4):397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin RV, Cummings SC, Coates TJ. Ethnicity and smoking: differences in White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian medical patients who smoke. Am J Prev Med. 1990;6(4):194–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triandis HC, Marín G, Lisansky J, Betancourt H. Simpatía as a cultural script of Hispanics. J Person Soc Psychol. 1984;47:1363–75. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazuda PH, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Eifler CW. Effects of acculturation and socioeconomic status on obesity and diabetes in Mexican Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(6):1289–1301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of overweight for Hispanics—United States, 1982–1984. MMWR. 1989;38:838–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marín G, Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R. Changes in information as a function of a culturally appropriate smoking cessation community intervention for Hispanics. Am J Comm Psychol. 1990;18(6):847–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00938067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marín BV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín G, Hauck WW. Effects of a community intervention to change smoking behavior among Hispanics. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:340–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce JP, Burns DM, Berry C, et al. Reducing tobacco consumption in California; Proposition 99 seems to work. JAMA. 1991;265(10):1257–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460100057019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]