Last Friday, I had a particularly busy clinic day. One of my first appointments was with a 23-year-old African-American man who described frequent episodes of feelings of doom, thundering and racing in his chest, and difficulty breathing. I diagnosed panic attacks. Knowing that depression is common among persons with panic attacks, I asked about his mood and discovered that he was suffering from major depression, a condition that had occurred once 4 years earlier when he entered college. After exploring issues concerning the etiology and appropriate treatment of his current problems, the patient and I elected medical therapy for his depression and referral to a behaviorist for his panic attacks. I felt good about the encounter, but it had taken 30 minutes, and I was 15 minutes late for my next appointment.

She was a middle-aged, obese, Hispanic woman with reasonably well-controlled diabetes. She had no specific complaints. While I was examining her feet and diagnosing osmidrosis, the previous patient popped into my mind, and I reminded myself that depression also was common among middle-aged women. Buoyed by the apparent success of my previous exploration of depression symptoms, I questioned her about her mood and her recent enjoyment and satisfaction with life. At first she didn't know what I was talking about, but as I made my questions clearer (and the interview longer), she clearly denied having any problems.

My next four patients were men over 60 years of age. Prodded by the lateness of my schedule, the lack of obvious psychiatric problems in these patients, and the rationalization that major depression is less common in men than women and in elderly than middle-aged persons, I queried none of them about depression. Rather, I adjusted antihypertensive regimens, pondered whether the laboratory had confused a glycosylated hemoglobin level with a serum hemoglobin value, and doled out an alpha agent for the patient with “chronic plumbing problems.” I finished clinic late and missed lunch, but for the most part, I thought I had done a pretty good job.

TARGETING DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES

The targeting of diagnostic strategies to high-risk individuals that is depicted in the above scenarios is typical of the reasoning many of us learn in medical school. We learn that diagnostic tests, including diagnostic interviews, are most likely to be useful in persons who have an intermediate chance of having the condition and that they are less likely to be useful in persons with a very low or high chance of having the condition.1 We often make the error of changing our diagnostic testing in response to the presence or absence of risk factors. The implicit assumption is that the risk factor has changed the likelihood of disease sufficiently to warrant change in our diagnostic strategy.

Diagnosis, however, is a multistage process. Information from different sources—clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory data—can assist clinicians to move logically from one step to the next. Risk factors have their own performance characteristics, and they may or may not help us move along the diagnostic ladder. In the above clinical scenarios, I based my decision to look further for major depression on the presence or absence of risk factors. Let us, however, examine more closely the impact of risk factors for major depression in helping us move from one step to the next in the diagnostic process.

RISK FACTORS AND RISK MAGNITUDES

My clinic patients were among those that participated in a recent research project examining major depression in primary care patients.2 From this project I was given feedback about the prevalence of major depression among clinic patients with certain characteristics. I was then able to calculate the actual magnitude of the risk associated with those characteristics. This information is depicted in Table 1 and is similar to risk estimates for gender and specific psychiatric illnesses that have been determined from community populations.3, 4 The clinically relevant question is: Does the presence or absence of a risk factor (e.g., female gender or panic attacks) change the probability of disease sufficiently to direct our decision to conduct a diagnostic interview for depression?

Table 1.

Risk Factors for Major Depression in a Primary Care Outpatient Population* (n=863)

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

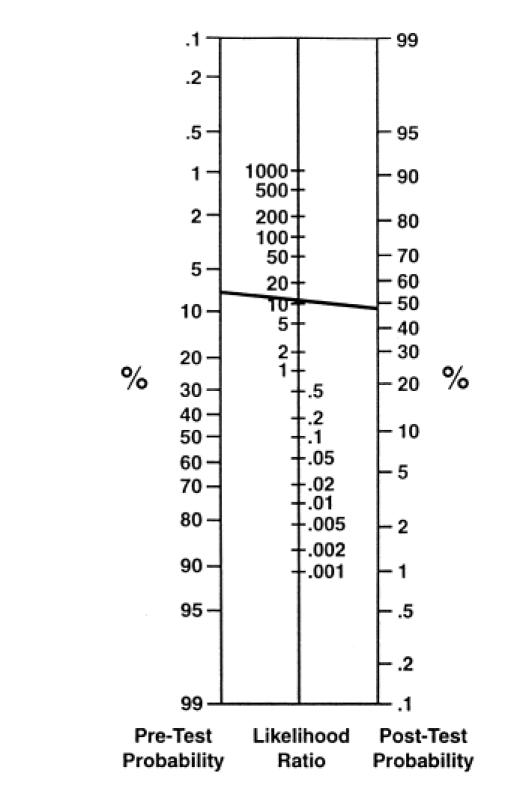

To address this issue, let us first review some basic principles of diagnostic testing. As reviewed earlier by Hatala et al., a useful tool for the clinician is the likelihood ratio (LR).5 This ratio expresses a given test result among patients with a certain disease relative to that of the same test result among patients without the disease. It can be used to convert the pretest probability of a disease, or the prevalence, to the posttest probability. The LR ranges from 0 to infinity. A ratio of 1 means that the pretest probability is the same as the posttest probability, while an LR>10 or <0.1 will greatly increase or decrease the pretest probability of disease. The LR for a positive test result is calculated as Sensitivity/(1 −Specificity); while the LR for a negative result is (1 −Sensitivity)/Specificity. Although these concepts may be difficult to grasp at first, a nomogram makes the application simple (Fig. 1). Knowing the prevalence of disease, one can apply the LR to the nomogram in Figure 1 and obtain the posttest probability of disease.

Figure 1.

Nomogram for diagnostic test interpretation. Example illustrates the effect of panic disorder (LR = ~11) on the probability of major depression. (Adapted from Fagan TJ. Nomogram for Baye's theorem (C). N Engl J Med. 1 975; 293:257.)

RISK FACTORS AND DISEASE PROBABILITY

Risk factors can be applied clinically like diagnostic tests. The magnitude of the risk is the strength of association between the risk factor and the target disorder and is often expressed in the literature as the odds ratio or relative risk, depending on the design of the study. Magnitudes of risk greater than 1 show a positive association between the risk factor and disease. An increased magnitude of risk, however, may not necessarily generate a useful increase in the probability of disease. The prevalence of the risk factor also needs to be considered.

The effect of LR on the posttest probability is a function of both the magnitude of the risk and the prevalence of the risk factor. The terms likelihood ratio and magnitude of the risk may seem confusing and similar; however, there is an important difference. While the magnitude of the risk is the strength of association between the target disorder and the risk factor, the LR is a concrete tool for assessing the clinical performance of the risk factor. As discussed above, it can be used to convert the pretest probability of a disease to a posttest probability.Figure 2 depicts the LR for varying risk factor prevalences and risk magnitudes.6 For any given magnitude of risk, the LR increases as the prevalence of the risk factor decreases.

Figure 2.

Likelihood ratio at various values of the prevalence of the risk factor and risk magnitude. (Adapted from Baron JA. The clinical utility of risk factor data. Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42 (10):1016.)

Female gender is the strongest demographic risk factor for major depression.7, 8 In the study population depicted in Table 1, women are roughly two times more likely than men to have the diagnosis of major depression (magnitude of risk approximately 2). Female gender has a prevalence of 70% in the population of primary care patients studied (Table 1). The combination of high prevalence and a relatively small magnitude of risk yields an LR close to 1 (LR = 1.2), which does little to change the probability of disease. I should not have made the decision to inquire about depression symptoms based on gender.

Conversely, let us examine the effect of a risk factor that is much less prevalent and associated with a higher risk magnitude. In our clinic population, panic disorder has a substantial risk magnitude of 12, while its prevalence is 2%. As shown in Table 1, its LR is approximately 11. Using the nomogram in Figure 1, the line connecting the pretest probability for major depression of 8% to the LR of 11 yields a posttest probability of 48%. Consequently, when panic disorder is present, the probability of major depression is increased from 8% to approximately 48%. In this example, a detailed diagnostic interview for major depression is clearly warranted. When panic disorder is absent, the likelihood ratio is 0.9; thus, there is no useful change in the pretest probability.

The above examples illustrate an important principle. To use risk factors correctly, one must consider both the associated magnitude of the risk and the prevalence of the risk factor. This consideration is done most readily by using the LR. Generally, risk factors that are uncommon have higher LRs and may increase significantly the suspicion of disease. Conversely, risk factors that are highly prevalent, such as female gender, tend to have lower LRs and have minimal effect on the probability of disease. Finally, for major depression, the absence of these risk factors does little to change the probability of disease.

QUESTIONNAIRES FOR DEPRESSION

An alternative approach recommended by some experts is to base selection of patients for diagnostic interviews on the results of brief, self-administered depression questionnaires. Numerous patient questionnaires exist that may increase the detection of depression in an unselected primary care population. A meta-analysis concluded that the nine commonly recommended questionnaires are comparable in their performance characteristics.9 The overall sensitivity of these questionnaires is 84% and specificity is 72%, thus yielding an LR of 2.9, which is significantly higher than the LRs for most readily available clinical characteristics for depression. The change in probability yielded by a positive patient questionnaire for depression in unselected outpatient primary care patients can provide the impetus to conduct a further detailed diagnostic interview for depression. Clearly, though, there are some risk factors for depression, such as panic disorder, that when present yield a very large LR and strongly warrant a careful diagnostic evaluation from the beginning.

DISCUSSION

We have seen that the usefulness of relying on a risk factor to help increase or decrease the suspicion of disease depends not only on the magnitude of the risk, but also on the prevalence of the risk factor. These principles have been demonstrated before in creative research work.6, 10 I had forgotten to apply them to my practice.

Risk factors can significantly increase the probability of disease when the prevalence of the risk factor is low and the associated magnitude is large, as with panic disorder. A diagnostic interview in patients with panic disorder or a “high-risk profile” is warranted because of the significantly increased probability of major depression. However, the prevalence of panic disorder and other high-risk profiles is low in a general primary care population. If depression interviewing were limited only to these individuals, a large number of persons with depression but without the high-risk profile would be missed. Conversely, other risk factors for major depression that are more prevalent, such as female gender, have a small magnitude of risk and do not usefully change the probability of disease.

Working through these case examples convinced me that limiting questions about major depression only to persons I thought were likely to be high risk was not the optimal strategy. Rather than attempting to efficiently “screen” for depression based on risk factors alone, we should be attuned to nonverbal cues and consider a routine question about mood or interest in day-to-day activities. Some practitioners do this regularly. Others may utilize patient questionnaires to aid in the detection of depression. A detailed diagnostic interview should then follow if warranted. Now I am later than ever in finishing clinic!

Summary Points

The diagnostic process is composed of a series of steps.

Risk factors can be applied clinically like diagnostic tests.

The clinical usefulness of a risk factor hinges on its associated magnitude of risk and its prevalence in clinical populations.

Risk factors may or may not significantly influence our diagnostic behavior enough to move us from one step to the next.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Award.

References

- 1.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. 2nd ed. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams JW, Mulrow CD, Kroenke K, Omori D, Badgett B, Dhanda R. Screening for depression: why ask 20 questions when 1 will do? J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(Suppl 1):S131. . Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276:293–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the national comorbidity survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–86. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatala R, Smieja M, Kane S, et al. An evidence-based approach to the clinical exam. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:182–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-5027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron JA. The clinical utility of risk factor data. Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(10):1013–20. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:977–86. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Gerety MB, Ramirez G, Montiel OM, Kerber C. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:913–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyko EJ, Alderman BW. The use of risk factors in medical diagnosis: opportunities and cautions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:851–8. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90068-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]