Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To study the effects of three approaches to increasing utilization of screening mammography in a public hospital setting in Northwest Louisiana.

DESIGN

Randomized intervention study.

POPULATION

Four hundred forty-five women aged 40 years and over, predominantly low-income and with low literacy skills, who had not had a mammogram in the preceding year.

INTERVENTION

All interventions were chosen to motivate women to get a mammogram. Group 1 received a personal recommendation from one of the investigators. Group 2 received the recommendation plus an easy-to-read National Cancer Institute (NCI) brochure. Group 3 received the recommendation, the brochure, and a 12-minute interactive educational and motivational program, including a soap-opera-style video, developed in collaboration with women from the target population.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Mammography utilization was determined at 6 months and 2 years after intervention. A significant increase (p = .05) in mammography utilization was observed after the intervention designed in collaboration with patients (29%) as compared with recommendation alone (21%) or recommendation with brochure (18%) at 6 months. However, at 2 years the difference favoring the custom-made intervention was no longer significant.

CONCLUSIONS

At 6 months there was at least a 30% increase in the mammography utilization rate in the group receiving the intervention designed in collaboration with patients as compared with those receiving the recommendation alone or recommendation with brochure. Giving patients an easy-to-read NCI brochure and a personal recommendation was no more effective than giving them a recommendation alone, suggesting that simply providing women in a public hospital with a low-literacy-level, culturally appropriate brochure is not sufficient to increase screening mammography rates. In a multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor of mammography use at 6 months was the custom-made intervention.

Keywords: mammography, utilization, public hospitals, low income, low literacy

Despite strong scientific evidence indicating the effectiveness of breast cancer screening and universal recommendation of expert groups, surveys routinely show underutilization of mammography among eligible women.1, 2 Underutilization of screening mammography may be particularly pronounced in public hospitals. Older women, minority women, and low-income women with limited education, groups commonly served by public hospitals, underutilize mammography.3–9 In public hospitals, limited literacy may be a hidden but potent barrier to effective cancer education, screening and treatment.10–12 Low literacy is a barrier well recognized by the National Cancer Institute (NCI).13

For these reasons, we developed an educational and motivational intervention with input of the target women. We elicited patient input on the focus, content, style, and wording of the message. Particular attention was given to making the message understandable, relevant, culturally sensitive, and empowering. The purpose of this study was to determine if this intensive, custom-made intervention was more effective than a personal recommendation or the combination of a recommendation and an easy-to-read NCI brochure in increasing utilization of screening mammography in a public hospital. The interventions were chosen specifically to motivate women rather than to impact the health care provider or the health care system.14

METHODS

The study design has been described in detail previously.15 In short, 445 women aged 40 years and over who had not had a mammogram in the past year and were waiting to see a physician in one of two outpatient clinics at Louisiana State University Medical Center–Shreveport (LSUMC-S), were enrolled in the study. The Ambulatory Care Clinic and the Eye Clinic were chosen because they have the longest waiting times and would allow time for patient enrollment. Patient reading ability was assessed with the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).16

The women were randomly assigned to one of three interventions. Randomization was based on the day of the week; each individual day was separately randomized to an intervention. This was done to allow scheduling of the different interventions on the same day. Group 1 received a personal recommendation from one of the investigators to get a mammogram. Participants in Group 2 were given the recommendation (as in Group 1) and an NCI brochure on mammography specifically designed for low literate women. Group 3 was given the recommendation (as in Group 1), the brochure (as in Group 2), and a custom-made 12-minute interactive motivational and educational intervention for small groups. The group was led by a peer educator and a cancer nurse using adult learning principles. The intervention included a 3 1/2-minute video, which was based on the results of focus groups held with low-income women. Barriers to and facilitators of mammography were identified; the women preferred a motivational rather than informational approach; and they suggested the message be given in story form like a “soap opera.”15

Six months after the intervention, mammography utilization was assessed in the study population with a search of LSUMC-S computerized mammography records. Because LSUMC-S is the only hospital in Shreveport providing care to the indigent population, it is extremely unlikely that women in this study population had a mammogram in another (private) hospital. At 6 months a telephone interview was also conducted to ask subjects if they had a mammogram during the preceding 6 months. Subjects were called three to five times if no answer was obtained. Subjects' self-reports of mammography were validated using the computerized records. A search of the mammography registry was repeated 2 years after the intervention. The mammography utilization rate at 6 and 24 months was calculated using the results of the linkage of the total study population with the mammography registry.

Statistical Analysis System (SAS), version 6.11, on an IBM PC was used to analyze the data. The demographic data of the population and data on mammography utilization at 6 and 24 months were compared among the different intervention groups using the χ2 test. Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate which variables, if any, were significant predictors of mammography utilization.

RESULTS

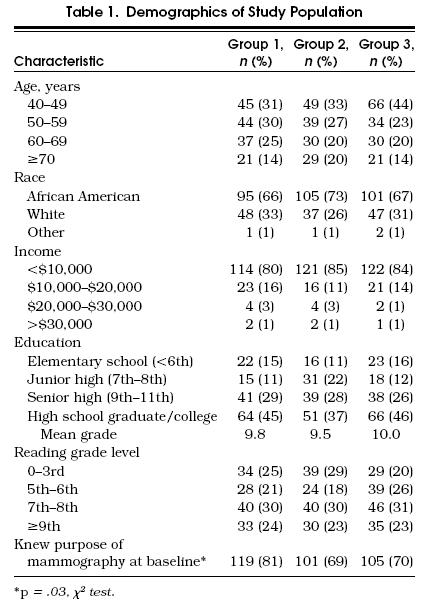

Overall, our study population consisted mainly of low-income women with limited literacy skills. The mean age of the participating women was 56 years; 69% were African American, and 30% were white; 97% lived in households with an annual income below $20,000 (Table 1) Fifty percent had not graduated from high school. The mean REALM raw score for all study participants was 40, indicating a 4th to 6th grade reading level. Ten percent of the women could not read any of the words on the test.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Population

The three intervention groups did not vary by age, race, income, education, or literacy level. However, they did vary by their baseline knowledge of mammography. Significantly (p < .05) more women in Group 1 knew the purpose of mammography (81%) compared with women in Group 2 (69%) or Group 3 (70%).

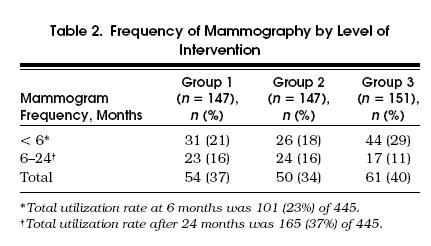

Six months after the intervention, a total of 101 women (23% of the total study population) had received a mammogram (Table 2) The difference in mammography utilization between the three intervention groups was statistically significant (p= .05) in the univariate analysis: of the women in Group 1, 31 (21%) of 147 received a mammogram as did 26 (18%) of 147 in Group 2 and 44 (29%) of 151 in Group 3. Women who knew the purpose of a mammogram at baseline were significantly more likely to have had a mammogram within 6 months (p= .02) after the intervention. In a multivariate analysis, however, adjusting for age, race, literacy level, and mammography knowledge, the difference between mammography utilization in the three intervention groups remained statistically significant (p= .03), and baseline knowledge was no longer related to mammography utilization. The custom-made intervention was the only significant factor (p= .01) in determining the probability of having a mammogram within 6 months.

Table 2.

Frequency of Mammography by Level of Intervention

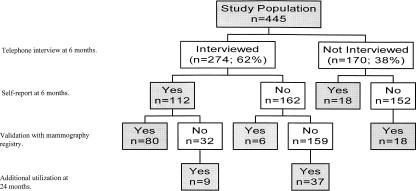

At 6 months after the intervention, we conducted a telephone follow-up interview (response rate 62%). Of the 274 women we were able to contact, 112 said they had had a mammogram in the previous 6 months. We validated these responses with the LSUMC-S mammography registry. The women for whom no record of a mammogram existed were considered not to have had one. Accuracy of self-report of mammography use was 87% (239 of 274; Fig. 1). Linkage with the mammography registry was repeated 2 years after the intervention, at which time a total of 165 women (37%) of the total study population had received a mammogram. This means that another 64 women had a mammogram 6 to 24 months after the intervention; 45 (70%) of these women were interviewed in the 6-month follow-up telephone survey.

Figure 1.

Mammography utilization. Total number of women who had a mammogram at 6 months was 101 (22.7%) of 445 and at 24 months 165 (37.1 %) of 445.

At 2 years after the intervention a total of 54 (37%) of the women in Group 1 had received a mammogram, 50 (34%) in Group 2, and 61 (40%) in Group 3 (Table 2). Although the highest utilization was still in Group 3, the differences between the three intervention groups 2 years after the intervention were no longer statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the relative effectiveness of three approaches, varying from a personal recommendation to a custom-made interactive program for small groups on mammography utilization by women in a public hospital. The custom-made program, developed and designed in partnership with target women and led by a peer educator and a cancer nurse, proved to be at least 30% more effective than the NCI brochure combined with a personal recommendation or a recommendation alone. The use of a colorful, easy-to-read NCI brochure in addition to a personal recommendation was no more effective than a recommendation alone. Our results suggest that simply giving patients in public hospitals low-literacy-level, culturally appropriate brochures will not be effective in improving mammography utilization. In fact, effort spent creating and distributing written educational materials for low-literate audiences may do little more than foster a false sense of security among health care providers. Moreover, despite the success of the custom-made intervention, utilization rates for mammography in all groups still fall far short of the year 2000 goal of 80%.17

At 2 years, differences in mammography utilization by intervention group had disappeared. In the period 6 to 24 months after intervention, 64 (14%) of the study population of 445 women had a mammogram. It is obvious that the effect of the intervention diminished after a short time. The fact that 46 (17%) of the 274 women who were contacted at 6 months after the intervention proceeded to get a mammogram indicates that our follow-up telephone call may have caused some women to have a mammogram.

Our personal, woman-to-woman, small-group program and warm, humorous video significantly influenced mammography utilization in the short term. This supports recent findings by Yancey et al. who reported that culturally sensitive videos increased cervical cancer screening in public health centers.18 Such videos may influence health behavior through affective as well as cognitive channels. In our study, both the content and format of the video and the patient education program were designed and executed in collaboration with target women. This reinforces the finding of Rudd and Comings that patient involvement in developing health education materials ensures that the content is relevant to the patients' situation and is presented from their viewpoint.19 Women in our focus groups 15 helped write and acted in the video; in addition, a woman in one focus group was hired as the peer educator. The effectiveness of our woman-to-woman program and video supports findings of focus groups of older African American women in the North Carolina Save Our Sisters Project that women turn to women they know with their health concerns.20 This also indicates that we need more input from patients concerning what information they require, how they want to receive it, and whom they want to deliver it.

In summary, we demonstrated a significant effect on mammography utilization in the short term (6 months) from a custom-made intervention. The beneficial effect of this one-time intensive intervention disappeared with longer follow-up (24 months). Successful interventions must be based on specific needs and characteristics of the target population, as determined by the members of the community themselves. The results of this study may not be generalizable in all public hospital settings. However, the principle of a custom-made intervention with full involvement of the target population is, in our opinion, likely to be effective in other settings as well.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute, grant 1R03-CA59235, and by the Cancer Center for Excellence in Research, Treatment and Education, Louisiana State University Medical Center in Shreveport.

References

- 1.Breen N, Kessler L. Changes in the use of screening mammography: evidence from the 1987 and 1990 National Health Interview Surveys. Am J PubIic Health. 1993;83:948–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakowski W, Rimer BK, Bryant SA. Integrating behavior and intention regarding mammography by respondents in the 1990 National Health Interview Survey of Health Promotion and Disease. Public Health Rep. 1994;84:62–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calle EE, Flanders WD, Thun MJ, Martin LM. Demographic predictors of mammography and Pap smear screening in US women. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:53–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimer BK, Trock B, Engstrom PF, Lerman C, King E. Why do some women get regular mammograms? Am J Prev Med. 1991;7:697–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, Constanze JE, Greene HL. Breast cancer screening by mammography utilization and associated factors. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1499–502. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.11.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplan L, Wells B, Haynes S. Breast cancer screening among older racial/ethnic minorities and whites: barriers to early detection. J Gerontol. 1992;47:101–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moormeier J. Breast cancer in black women. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:897–905. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-10-199605150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns R, McCarthy E, Freund K, et al. Black women receive less mammography even with similar use of primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:173–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandelblatt J, Andrews H, Kao R, Wallave R, Kerner J. Impact of access and social context on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1995;6:342–50. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274:1677–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles S, Davis T. Patients who cannot read: implication for the Health Care System. JAMA. 1995;274:1719–20. . Editorial. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doak CC, Doak LG. Teaching Patients with Low-Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Work Group on Cancer and Literacy . Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; May 7 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy B, Yood M, Bolton M, Boohaker E, MacWilliams C, Young M. Redesigning primary care processes to improve the offering of mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:357–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis T, Arnold C, Berkel H, Nandy I, Jackson R, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996;78:1912–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961101)78:9<1912::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:256–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington DC: U.S. Printing Office; 1991. pp. 114–5. 72. DHHS publication (PHS) 91-50213. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yancey A, Tanjasiri S, Klein M, Tunder J. Increased cancer screening behavior in women of color by culturally sensitive video exposure. Prev Med. 1995;24:142–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudd RE, Comings JP. Learner developed materials: an empowering product. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:313–27. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eng E. The Save Our Sisters Project: a social network strategy for reaching rural black women. Cancer. 1993;72:1071–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3+<1071::aid-cncr2820721322>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]