Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare the health characteristics and service utilization patterns of homeless women and low-income housed women who are heads of household.

DESIGN

Case-control study.

SETTING

Community of Worcester, Massachusetts.

PARTICIPANTS

A sample of 220 homeless mothers and 216 low-income housed mothers receiving welfare.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Outcome measures included health status, chronic conditions, adverse lifestyle practices, outpatient and emergency department use and hospitalization rates, and use of preventive screening measures. Both homeless mothers and housed mothers demonstrated low levels of physical and role functioning and high levels of bodily pain. Prevalence rates of asthma, anemia, and ulcer disease were high in both groups. More than half of both groups were current smokers. Compared with the housed mothers, homeless mothers reported more HIV risk behaviors. Although 90% of the homeless mothers had been screened for cervical cancer, almost one third had not been screened for tuberculosis. After controlling for potential confounding factors, the homeless mothers, compared with the housed mothers, had more frequent emergency department visits in the past year (adjusted mean, homeless vs housed, 1.41 vs .95, p = .10) and were significantly more likely to be hospitalized in the past year (adjusted odds ratio 2.22; 95% confidence interval 1.13, 4.38).

CONCLUSIONS

Both homeless mothers and low-income housed mothers had lower health status, more chronic health problems, and higher smoking rates than the general population. High rates of hospitalization, emergency department visits, and more risk behaviors among homeless mothers suggest that they are at even greater risk of adverse health outcomes. Efforts to address gaps in access to primary care and to integrate psychosocial supports with health care delivery may improve health outcomes for homeless mothers and reduce use of costly medical care services.

Keywords: homelessness, health status, women's health, service utilization, primary care

Homelessness remains a persistent and growing problem nationwide. A telephone survey of 1,507 household-based participants published in 1994 reported that 13.5 million (7.4%) of adult Americans had experienced homelessness at some point in their lives.1 Most agree that homeless families, the majority of which are headed by women, are increasing in number and now constitute more than one third of the overall homeless population.2

Numerous reports have described the health care needs of various homeless subgroups, with most addressing the health problems of adult individuals and children.3–12 Surprisingly, the literature offers little information about the health status and service use patterns of homeless female heads of household and how their health and health care patterns compare with those of their housed counterparts. Although several descriptive reports and studies on homeless adult individuals have included female heads of household as part of the sample,3, 4, 7, 10 they have not reported specifically on the health needs of these women. A few studies have examined general health,9, 13, 14 reproductive health,15, 16 substance abuse,9, 11, 16–19 and other risk behaviors,20, 21 among homeless female heads of household. These studies, however, are limited by a lack of comparison groups,9, 13–16, 20, 21 small sample sizes,13, 16, 17, 21 biased samples of service users,14 and lack of standardized instruments for assessing health status 9, 13–16 and risk behaviors.9, 11, 16, 18, 21 No large-scale studies thus far have examined the health care needs of homeless female heads of household.

As part of a large epidemiologic study of sheltered homeless families and poor housed families in Worcester, Massachusetts,22 data were collected on the physical health and health service utilization patterns of study subjects. Trained study staff administered a comprehensive in-person interview to 220 sheltered homeless and 216 low-income housed female heads of household. Women were questioned about their past and present health status, history of acute and chronic conditions, risk behaviors, and access to and use of medical services. In addition, detailed information about income and housing, support networks, victimization, and mental health was collected.

The present study examines the special health needs of homeless women and how their needs compare with those of other poor women with dependent children. Understanding their health needs in a systematic manner will help us to improve policies for and programmatic interventions in this high-risk population.

METHODS

Study Population

A case-control design was used to recruit a sample of sheltered homeless families and a comparison group of low-income housed (never homeless) families in Worcester, Massachusetts. Worcester, located in the central part of Massachusetts, is the second-largest city in New England, and has a population of approximately 169,000 (1990 U.S. Census estimates).

In Massachusetts, more than 95% of homeless families and families receiving Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) are headed by women, so we enrolled only female-headed families with children under 17 years of age who were living with their mothers. We used the U.S. Congress's definition of “homeless,” which is having spent more than 7 consecutive nights in a car, abandoned building, public park, shelter, nonresidential building, or other nondwelling (Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, 11301 et seq, 42 USC 1987; amended 1988). Unlike homeless single adults, who are found on the streets as well as in shelters, homeless families tend to be limited to shelters.23

During the period from August 1992 to July 1995, we enrolled 220 homeless families from all nine of Worcester's emergency and transitional shelters, as well as two welfare hotels (3.2% of subjects). Hotels are used to house families when there is a shortage of shelter beds. Study staff asked all families who had been in a shelter for at least 7 days to participate in a multisession interview. As the maximum shelter capacity in Worcester is approximately 70 families, we enrolled more families as they became homeless. Of the 361 homeless families we approached, 102 refused to participate and another 39 dropped out of the study before completing the interview sessions. Information on the reasons for nonparticipation was not collected. No significant differences with respect to race, marital status, number of children, and welfare status were found between women who completed the study and those who refused. Homeless women who refused to participate were slightly younger and less likely to have graduated high school than those who completed the study. In only a few instances were we unable to enroll families owing to logistical or confidentiality constraints within the shelters. The homeless women who dropped out of the study (15% of homeless women enrolled) were similar to survey participants in terms of age, race, number of children, and ethnicity.

We enrolled a comparison group of 216 families from never-homeless female-headed households receiving AFDC who came to the Worcester Department of Public Welfare (DPW). Although we considered enrolling families from public housing or neighborhood health clinics, it was decided that AFDC recipients were most representative of the base population from which homeless cases emerged. To select a random sample of low-income, never-homeless women, interviewers (including Spanish-speaking interviewers) were stationed at the DPW office on rotating days of the week. All women who entered the office for a regularly assigned redetermination meeting were approached and screened for previous homelessness. Although it would have been ideal to construct a sampling frame, this was not possible for confidentiality reasons. (Rather, we capitalized on the routine redetermination meetings, a random process that was already in place.) Toward the end of the study, DPW changed the redetermination rules, at which point we opened enrollment to all women coming to the DPW, regardless of reason.

A total of 395 women were approached; 148 refused to participate, and another 31 did not complete the interview series. Housed women who refused to participate were similar to the study sample with respect to age, marital status, and number of children. They were significantly less likely, however, to have completed high school and slightly more likely to be Puerto Rican. Compared with the study sample, housed women who dropped out during the study (12% of housed women enrolled) were less likely to have graduated high school but were otherwise similar. Further detail is provided about the study's sampling strategy in previous publications.22

Data Collection

Women completed four interview protocols in a series of three to four sessions that lasted a total of approximately 10 hours. Interview sessions were organized by topic (e.g., session 1 included demographic, economic, and support information). The multisession format reduced respondent fatigue and allowed time for the interviewers and respondents to establish a relationship. Homeless women were interviewed in a private space at each shelter. Housed women completed the interviews in their homes or at a community-based project office. Informed consent was obtained prior to the initial interviews. As an incentive to participate in each interview session, women received $10 vouchers redeemable at local stores. The study received approval from the University of Massachusetts Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

A structured interview was developed to gather information about demographic, income, and housing characteristics of subjects. Standardized instruments were chosen on the basis of their successful use with low-income and minority populations. When available, existing Spanish versions of standardized instruments were used. Bilingual and bicultural translators translated all other questions into Spanish. Given the sensitive nature of some questions, all interviewers were female. Interviewers held a bachelor's or master's degree in an applied field such as social work or psychology. Interviewers received intensive training on all interview segments. Several interviewers were fluent in Spanish.

Main Outcome Measures

Health Status.

The 36-Item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-36) is a commonly used scale that measures self-perceived health status in the past 4 weeks.24 Subscales that we examined were physical functioning (10 items), role functioning–physical (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), and social functioning (2 items). The scores for each scale range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better functioning. High internal consistency and discriminant validity for these scales have been shown across groups with varying clinical problems and sociodemographic characteristics.25 Within the Worcester Family Research project, subscales showed strong internal consistency with the following coefficient α values: physical functioning, .90; role physical, .89; pain, .82; and social functioning, .73.

Service Use and Preventive Practices.

Service use was measured by three questions that asked study participants about the number of outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and medical-related hospitalizations they had encountered in the past year. In addition, each woman was asked about the frequency (never to 5+ years) of preventive practices, including screenings for blood pressure, cervical cancer, and tuberculosis. The frequency of HIV testing was determined by a single question about the number of times the subject had been screened for HIV. (Women were also asked about their knowledge of HIV transmission.) To enable us to derive comparisons with other data services, these questions were adapted from national surveys and clinical guidelines.26–28

Chronic Conditions and Risk Behavior.

Respondents were asked about the presence of 22 lifetime and current chronic health condition. Eight current conditions (anemia, asthma, chronic bronchitis, hypertension, cancer, epilepsy, diabetes, and peptic ulcer) were combined to create a chronic condition count. Women were also asked about adverse lifestyle practices (i.e., cigarette smoking, obesity defined as>20 lb overweight, intravenous drug use, or alcohol or substance abuse or dependence). These lifestyle behaviors were combined to create an indicator of high-risk practices. Further information gathered included number of lifetime sexual partners, number of sexual partners in the past 6 months, and whether women had past sexual partners who were HIV positive. Questions in this area were derived from national surveys.25, 26

Mental Health and Violence.

Lifetime and 6-month prevalence of Axis I depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol or drug abuse and dependence were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Non-Patient Version.29, 30 Childhood and adult violence victimization was assessed using a contextualized version of the Conflict Tactics Scale.31

Demographic Characteristics.

Background information on age, race, ethnicity, education, and residential history was collected using the modified Personal History Form.32 The size of each woman's social support network at the time of the interview was determined by counting the number of persons listed in the Personal Assessment of Social Supports (PASS).33 Further description of measures utilized in this study has been provided elsewhere.22

Data Analysis

Differences in the distribution of selected characteristics between homeless and housed women were examined with the use of χ2and Student's t tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All tests of statistical significance were two-tailed. The simultaneous effect of various potentially confounding variables that might influence the outcomes examined in the homeless women as compared with the housed women was controlled for by means of logistic regression analysis for categorical variables and linear regression for continuous variables. The variables controlled for in each of the regression analyses included age, race, income, education, number of moves in the past 2 years, lifetime prevalence of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder or alcohol or drug dependence, support network, history of childhood sexual or physical abuse, and adult violence by an intimate. Service use outcomes included hospitalization in the past year as another covariate. The controlling variables were included because of the possibility of a priori confounding by these factors as well as based on the univariate comparison of differences in the distribution of these characteristics between homeless and housed women. A p value <.15 was used as the criterion for inclusion in the regression model. Poisson regression was used to confirm the results of the linear regression models.

RESULTS

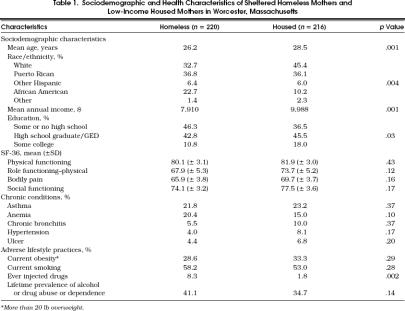

A total of 220 homeless mothers and 216 housed mothers participated in the study and completed all interview sessions. In examining differences in various sociodemographic characteristics between the comparison samples (Table 1), we found that homeless mothers were significantly younger than their housed counterparts and less likely to have completed a high school education or received a general equivalency diploma (GED). Although both groups were living below the federally established poverty level, homeless mothers, compared with housed mothers, had significantly lower annual incomes and were less likely to have received welfare in the prior year. More frequent moves during the past 2 years (3.8 vs 1.8, p < .001), and fewer nonprofessional supportive relationships (4.0 vs 4.6, p <.001), were reported by homeless mothers than by housed mothers. At the time of the survey, 13% of homeless women and 5% of housed women were pregnant (p < .005).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Sheltered Homeless Mothers and Low-Income Housed Mothers in Worcester, Massachusetts

The rates of childhood and adult victimization were high for both the homeless and housed respondents, despite nonsignificant differences between these groups.22 A majority of women reported severe violence by an adult partner (63% homeless vs 58% housed). Almost half of both groups reported childhood sexual molestation (43% homeless vs 42% housed), and a large proportion (67% homeless vs 60% housed) had experienced severe physical abuse as a child. A significantly greater proportion of homeless mothers, however, had experienced at least one of these forms of violence during their lifetime (88% homeless vs 79% housed, p < .05). For homeless and housed women, respectively, lifetime prevalence rates of DSM-IIIR psychiatric disorders were high compared with those of the general population,22 and were as follows: depression (45% vs 43%), posttraumatic stress disorder (36% vs 34%), and alcohol or drug abuse or dependence (41% vs 35%).

In examining health characteristics in the respective comparison groups (Table 1), the average scores on the SF-36 subscales are relatively comparable. Relatively high prevalence rates of asthma, anemia, and ulcer disease were reported by both homeless women and housed women. Almost one half of both groups reported the presence of at least one chronic condition. One quarter of both homeless women and housed women reported their health to be fair or poor.

In terms of lifestyle characteristics (Table 1), significantly more homeless women reported use of injectable drugs at some point in the past. In examining the distribution of the lifestyle characteristics studied, 16% of homeless women reported the presence of three or more of these factors; 9% of housed women reported that they engaged in three or more of these lifestyle practices.

Two homeless women (1%) and one housed woman (.05%) reported that they were HIV positive. Approximately 10% of homeless women and 6% of housed women reported that they perceived themselves to be at either medium or high risk of HIV infection (p < .001). Significantly more homeless women had received HIV testing in the past as compared with housed women (p < .01). Levels of knowledge about modes of HIV transmission were high in both groups, with the majority of women stating that HIV can be transmitted through sexual intercourse (homeless vs housed, 93% vs 97%) and from a pregnant woman to her baby (homeless vs housed, 76% vs 81%).

With regard to sexual activity, differences between homeless and housed women were significant with regard to average number of lifetime partners (homeless vs housed, 7.2 vs 5.4, p < .05) and in the proportion of women who had two or more sexual partners during the past 6 months (homeless vs housed, 14.7% vs 7.4%, p < .05). A small number of both groups reported having sexual partners in the past 5 years who were HIV positive (homeless vs housed, 4% vs 1%, p < .05).

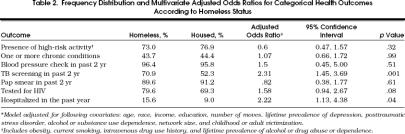

A majority of both groups had received preventive care recommended for this age group (Table 2 28 Although the majority of the homeless and housed women had received blood pressure and cervical cancer screening in the past 2 years, a significant percentage of both groups had never been screened for HIV or tuberculosis. Compared with the housed mothers, the homeless mothers were significantly more likely to have received tuberculosis screening in the past 2 years.

Table 2.

Frequency Distribution and Multivariate Adjusted Odds Ratios for Categorical Health Outcomes According to Homeless Status

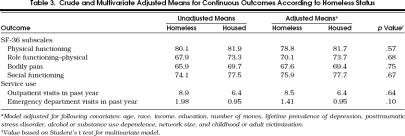

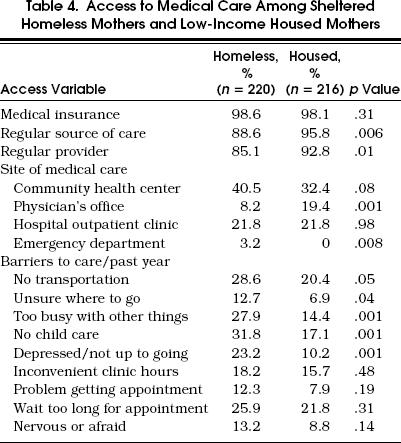

Service utilization patterns, as measured by emergency department and outpatient visits (Table 3), and hospitalizations in the past year (Table 2), differed between homeless women and housed women, with significantly higher emergency department and hospitalization rates seen in the homeless. The higher emergency department utilization patterns of homeless women may, in part, be explained by the significantly lower percentage of these women who either are able to identify a regular source of care when sick or have a regular health care provider (Table 4 Homeless women were more likely than housed women to receive their medical care at community health centers and less likely to receive their care at a physician's office. Although both groups had high rates of hospitalization in the past year, the homeless were almost twice as likely to be hospitalized as their housed counterparts. Among homeless women, the main reasons cited for hospitalization were gastrointestinal illness (13%), respiratory illness (13%), and trauma-related causes (13%). Among housed women, the primary mentioned reasons for hospitalization were gastrointestinal illness (19%), infectious diseases (19%), genitourinary causes (16%), and gynecologic-related problems (16%).

Table 3.

Crude and Multivariate Adjusted Means for Continuous Outcomes According to Homeless Status

Table 4.

Access to Medical Care Among Sheltered Homeless Mothers and Low-Income Housed Mothers

Ninety-one percent of homeless women and 90% of housed women had seen a physician in the past year. Two thirds of homeless women and half of the housed women reported that they did not get needed medical care or that medical care had been delayed in the past year. Barriers that women encountered in seeking medical care during the past year are described in Table 4.

Crude and multivariate adjusted risks for categorically defined health outcomes in homeless as compared with housed women are shown in Table 2. After controlling for previously described covariates, homeless women were significantly more likely than housed women to have been tested for tuberculosis in the past 2 years. When controlling for other factors that might affect hospitalization rates, homeless women were significantly more likely to be admitted to the hospital during the past year.

Crude and multivariate adjusted differences in the SF-36 subscale scores as well as service utilization patterns expressed in a continuous manner were examined in both groups (Table 3). No significant differences related to health status were seen between the two groups. There was a trend for homeless women to report more frequent emergency department visits than did housed women. A Poisson regression approach confirmed the linear regression results with regard to the association of homeless status and service utilization patterns. Therefore, only linear regression results are reported.

Because there was a greater proportion of pregnant women or women who had recently delivered a baby among the homeless group, which could account for greater use of outpatient care, we carried out another subgroup analysis in which we excluded women who were pregnant at the time of the survey or had delivered a baby during the prior 12 months. Results of this analysis showed trends in a similar direction to that observed in the total study sample with more frequent outpatient visits among the homeless (adjusted mean = 6.6 visits per past year) as compared with housed women (adjusted mean = 5.0 visits per past year).

DISCUSSION

This is the first comprehensive epidemiologic study to examine the health status and service use patterns of sheltered homeless women and low-income housed women with dependent children. The comparison of homeless mothers and housed mothers demonstrated important similarities and noteworthy differences. A higher percentage of women in both groups suffered from chronic medical conditions and limitations in functioning when compared with the general population. The majority of both homeless women and housed women were cigarette smokers. Similarly, both groups had experienced extremely high rates of victimization as children and adults, and struggled with common posttrauma sequelae including posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive illness, and substance abuse disorders.22 On a variety of health-related outcomes, however, important differences were identified between the groups, with homeless mothers reporting more HIV risk behaviors, and higher rates of emergency department use and hospitalization during the past year.

Health Status

Among both the sheltered homeless and low-income housed groups, rates of asthma were more than 4 times higher, anemia between 6 and 8 times higher, and ulcer disease, 3 to 5 times higher when compared with a general population sample of women under 45 years of age.34 Our study appears to demonstrate higher prevalence rates of anemia and asthma when compared with prior studies of homeless mothers, though direct comparisons are impossible owing to differences in how these conditions were classified.9, 14 The high comorbidity rates observed in the present study could be the result of biases in self-reported data; unfortunately, we were unable to validate women's self-reports with review of medical records or by some other means. However, a recent report described that, if anything, less-educated persons tend to underreport chronic conditions on health interview surveys.35 The high rates observed in the present study may reflect, however, the particular characteristics of our study population and the high degree of poverty and other environmental stressors in poor women's lives.

Although not significantly different from one another, both groups experienced lower levels of all measured dimensions of health status compared with a general population sample of women between 25 and 34 years of age.36 Homelessness per se did not independently predict poorer physical health status. However, the housed cohort in this study had moderate residential instability and equally poor outcomes in many of the measures of well-being. This may partly account for why homelessness was not significantly associated with poor health status.

The health status results are not surprising, given the high prevalence rates of medical conditions found in both groups. A disproportionate percentage of homeless and housed women reported their health status as fair to poor compared with a national sample of comparably aged women,27 findings that could, in part, explain the diminished functioning reported. The high rates of childhood and adulthood victimization may also explain the limited functioning reported by women in this study. Short-term and long-term physical health sequelae of victimization experiences have been described in numerous reports.37, 38

Adverse Lifestyle Practices

The smoking rates that we observed are more than twice that of the general female population and considerably higher than those found in samples of low-income populations or ethnic minorities.39, 40 The high rates of smoking may, in part, explain the high prevalence rates of asthma reported in both groups. The markedly elevated smoking rates may reflect our study sample's high rates of lifetime substance or alcohol abuse or dependence.41 Studies have also suggested an association between smoking and major depression, another condition with high prevalence rates in our sample.41 Importantly, alcoholism and major depression may exert detrimental effects in smoking cessation efforts.42 Health programs for homeless and low-income populations should include smoking cessation as an integral component of care. Success rates may be enhanced by incorporating treatment strategies for depression or substance abuse when indicated.

Homeless mothers appear to be at higher risk of HIV infection than low-income housed mothers. Homeless mothers were more likely to perceive themselves as being at medium or high risk of having HIV, a perception that may reflect their reportedly more frequent high-risk practices including multiple sexual partners, sexual partners who were positive for HIV, and a history of intravenous drug use. It is not immediately clear why homeless mothers are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors for HIV. It may be that the disruptiveness of frequent housing changes and the experience of extreme poverty in the homeless group increases the likelihood of high-risk practices. In addition, homeless mothers' greater isolation from support networks and more severe victimization histories may lead to despair and erode protective behaviors. One previous study of homeless minority women, for example, demonstrated more high-risk behaviors in women with more emotional distress and lower self-esteem.20

The extreme poverty, isolation, and residential instability that are associated with women's homelessness may also contribute to relationships in which they are more economically and socially dependent on men, thereby making it more difficult to make demands for protective behaviors. Irrespective of the reasons for the observed differences between the groups, HIV prevention and screening efforts that are geared to the special needs of homeless mothers should accompany other health and social service activities for this high-risk group. Interventions must attend to the realities of homeless mothers' lives and strive to diminish their emotional distress, build supportive relationships, and improve economic self-sufficiency.

Service Access and Utilization

The data revealing good access to a regular provider and high rates of preventive screening practices for both groups of women probably reflect the study community's well-established and organized system of health care for low-income and homeless families and may not accurately represent access barriers faced in other communities. Other studies of low-income women have reported lower rates of health screening than those observed in this study population.43 However, housing status still emerges as a key covariate in distinguishing the groups with regard to tuberculosis screening and HIV testing. The homeless group's greater use of preventive care may be related to the link with medical services that shelters provide for women and the greater encouragement they most likely receive to partake of these services. The fact, however, that one third of homeless mothers had not been screened for tuberculosis, despite frequent medical contacts and preventive guidelines suggesting this measure,28 highlights the need to educate health providers about tuberculosis risk among homeless populations.

Service utilization rates appear to be an important distinguishing feature between sheltered homeless mothers and low-income housed mothers. There was a trend for homeless mothers to have more frequent emergency department visits than the housed group even after controlling for other factors that could have, in part, accounted for observed differences in health care utilization. Although we cannot comment on the nature of the emergency department visits, the fact that homelessness is associated with more emergency care use, in the context of most women having a regular source of care, suggests gaps in access to primary health care services for this population. Our data demonstrate that homeless mothers, compared with housed mothers, are more likely to report particular barriers, such as lack of transportation, to the receipt of health care. This could encourage the use of emergency departments, which offer flexibility and accessibility compared with outpatient settings.

Several other factors could account for these higher service utilization rates among homeless mothers. Shelters typically link women with local services, perhaps leading to higher rates of medical care utilization. Even though the majority of both groups of women reported having a regular health care provider, the homeless were less likely to have one, a factor that could lead to greater use of emergency department care. The stress and disruption of the homeless experience itself may also contribute to higher service use. For example, delays in receiving timely services owing to competing demands may lead to more serious illness and the need for emergency care. Finally, higher emergency department use by homeless mothers may suggest that they are experiencing other health problems that we failed to capture. Homeless mothers' higher emergency service utilization may be appropriate to their underlying health problems or, possibly, the result of a health system that is overlooking their genuine needs.

Most strikingly, the rate of hospitalization among homeless mothers was 4 times that of a national sample of comparably aged women.34 After controlling for potentially confounding variables, homeless mothers were approximately 2-fold more likely than the low-income housed mothers to have been hospitalized for a medical problem in the past year. This high rate of hospitalization among homeless mothers is cause for concern and important to understand in the present era of managed care and cost containment. Whether these high hospitalization rates reflect physical health problems that are unique to this population, or due to stress or other factors associated with homelessness, cannot be answered by this study. It is certainly possible among the homeless group that higher rates of hospitalization reflect a delay in receiving treatment for diseases early in their course. In addition, although the majority of women in both groups failed to escape severe victimization experiences in their lifetime, the significantly higher cumulative rate of victimization among homeless mothers and its associated mental and physical health sequelae may partially explain their higher hospitalization rate. Disentangling the reasons for hospitalization among homeless women requires further analysis in order to develop cost-effective interventions that will address their needs and ameliorate their concerns.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Other researchers have provided descriptive data about homeless mothers' physical health,9, 11, 17, 18, 44 but this is the first study to provide an in-depth examination of health status and medical service use, and to examine the independent contribution of homelessness to health and service use after controlling for other variables that may confound these associations. However, several limitations need to be considered in reviewing the present results. The sample was drawn from a city with a distinct ethnic composition that included proportionately more Hispanics and fewer African Americans than in other cities.14, 45 Thus, the findings can be best generalized to midsized cities with a similar ethnic mix. As mentioned above, slight differences were noted between the study sample and women who either refused to participate or dropped out during the interviews. Although we believe selection bias was small, this could limit the study's representativeness on measures that were not compared. In addition, no validation was attempted through review of medical records or other sources to verify the respondents' self-reported data. Although unknown, it is unlikely that these data would be differentially reported according to homeless status. The study's definition of homelessness also excluded women with extremely short shelter stays and those who were doubled-up in living arrangements with family and friends. Homeless adult women living without families, many of whom are mothers who have lost custody of their children, were also not represented in the sample.

Conclusions

The composite that emerges from this comprehensive study of sheltered homeless mothers' and low-income housed mothers' health is one of significant illness burden for both groups, particularly when considering their young age. Even though access to preventive services and treatment appears good and is probably unique to Worcester, Massachusetts, both homeless mothers and low-income housed mothers have serious health conditions and adverse lifestyle practices that place them at high risk of further adverse health outcomes. Our findings suggest that homeless mothers are at even higher risk of poor outcomes because they have more HIV risk behaviors and possibly more illness. The disproportionate use of emergency department services and hospitalization by the homeless group points to potential access problems, as well as serious cost implications, which requires further study.

The problem of family homelessness, which has been described for many years, is likely to increase with the recently enacted welfare reform law. Structural changes that eliminate homelessness through developing increased affordable housing, and improve all low-income mothers' capacity to earn a livable wage, and have access to child care, will ultimately be necessary to improve their health status. In the meantime, the health care setting provides an important avenue to recognize and respond to homeless and low-income mothers' important health needs as well as the complex range of psychosocial issues that affect their health. Special primary care approaches that integrate risk reduction and violence intervention strategies while addressing current health problems will most likely lead to more favorable outcomes in these high-risk women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH47312 and MH51479) and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCJ250809).

The authors acknowledge the important contributions of the following persons in the conduct of this research: project interviewer staff, Nancy Popp, EdD, Meg Brooks, Ellen Bassuk, MD, Angela Brown, PhD, John Buckner, PhD, and Amy Salomon, PhD; and Ellen Bassuk, MD, and Brad Rose, PhD, for their comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Link B, Susser E, Steve A, Phelan J, Moore R, Strenning E. Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1907–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Conference of Mayors . A Status Report on Hunger and Homelessness in America's Cities: 1995. Washington, DC: US Conference of Mayors; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright J. Poor people, poor health: the health status of homeless. J Social Issues. 1990;46:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelberg L, Linn L. Assessing the physical health of homeless adults. JAMA. 1989;262:1973–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usherwood T, Jones N, the Hanover Project Team Self-perceived health status of hotel residents: use of the SF 36-D health survey questionnaire. J Public Health Med. 1993;15(4):311–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelberg L, Linn L, Usatine R, Smith M. Health, homelessness and poverty. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2325–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright J, Weber E. Homelessness and Health. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson M, Cousineau M. Health status and access to health services among urban homeless. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(5):561–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker R, Rescorla L, Finklestein J, Barnes N, Holmes J, Stolley P. A survey of the health of homeless children in Philadelphia shelters. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:520–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160050046011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkleby M. Comparison of risk factors of ill health in a sample of homeless and non-homeless poor. Public Health Rep. 1990;105(4):404–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood D, Valdez R, Hayashi T, Shen A. Homeless and housed families in Los Angeles: a study comparing demographic, economic, and family functioning characteristics. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1049–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.9.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller D, Lin E. Children in sheltered homeless families: reported health status and use of health services. Pediatrics. 1998;81:668–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adkins C, Fields J. Health care values of homeless women and children. Fam Commun Health. 1992;15(3):20–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rog D, McCombs-Thornton KL, Gilbert-Mongelli A, Brito M, Holupka C. Implementation of homeless families program, 2: characteristics, strengths and needs of participant families. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:514–28. doi: 10.1037/h0079675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavkin W, Kristal A, Seabron C, et al. The reproductive experience of women living in hotels for the homeless in New York City. NY State J Med. 1987;87:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner J, Menke E. Substance abuse by homeless pregnant mothers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1992;3:93–106. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassuk EL, Rubin L, Lauriat A. Characteristics of sheltered homeless families. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:1097–1101. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.9.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitzman B, Knickman J, Shinn M. Predictors of shelter use among low income families: psychiatric histories, substance abuse and victimization. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1547–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith E, North C, Spitznagel E. Alcohol, drugs and psychiatric comorbidity among homeless women: an epidemiologic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:82–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyamathi A. Relationship of resources to emotional distress, somatic conflicts and high-risk behaviors in drug recovery and homeless minority women. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14:269–77. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christiano A, Susser I. Knowledge and perceptions of HIV infection among homeless pregnant women. J Nurse Midwifery. 1989;34:318–22. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(89)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassuk E, Weinreb L, Buckner J, Browne A, Salomon A, Bassuk S. The characteristics and needs of sheltered homeless and low income housed mothers. JAMA. 1996;276:646–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Flaherty B. Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Sherbourne DC. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Status Survey, I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1991;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JFR, Sherbourne DC. The MOS36-item short-form Health Survey (SF-36): III: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams PF, Benson V. National Center for Health Statistics. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1989. Vital Health Stat 10. 1990:176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoenborn CA. Vital Health Stat 10. 1989. National Center for Health Statistics. Health promotion and disease prevention: United States, 1985; p. 163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Preventive Services Task Force . Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, William JBW, Gibben M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Non Patient Edition (SCID-NP, version 1.0) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed, revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller BA, Downs WR, Gondoli DM, Keil A. The role of childhood sexual assault in the developement of alcoholism in women. Vilence Vict. 1987;2:157–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrow S, Hellan R, Lovell A, et al. Personal History Form. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunst CH, Trivett CM. Personal Assessment of Social Support Scale. Moranton, NC: Family, Infant and Preschool Program, Western Carolina Center; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey, 1993. Vital Health Stat 10. 1994:188–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackenebush J, Looman C, Van der Meer J. Differences in misreporting of chronic conditions by level of education: the effect of inequalities in prevalence rates. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:706–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey, Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Mass: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association Violence against women. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leserman J, Toomey T, Drossman D. Medical consequences of sexual and physical abuse in women. Humane Med. 1995;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors—United States. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1994;43(SS-3):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Stat 10. 1990:185. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covey L, Hughes D, Glassman A, Blazer D, George L. Ever-smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disorders: evidence from Durham, North Carolina, Epidemiologic Catchment Area. Tobacco Control. 1994;3:222–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Covey L, Glassman A, Stetner F, Becker J. Effect of history of alcoholism or major depression on smoking cessation. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1546–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makuc D, Freid V, Kleinman J. National trends in the use of preventive health care by women. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:21–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zima BT, Wells KB, Benjamin B, Duan N. Mental health problems among homeless mothers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:332–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.1990 Census of Population . Metropolitan Areas. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 1990. [Google Scholar]