Abstract

Associations between specific foot-care behaviors and foot lesions in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus were prospectively investigated. Data from a randomized controlled trial for preventing diabetic foot lesions were analyzed as a prospective cohort using logistic regression. Independent variables included foot-care behaviors, patient self-foot examination, going barefoot, availability of foot-care assistance, and visits to health-care providers. The dependent variable was a foot wound on each foot at follow-up. In the final multivariate model, patients who rarely lubricated their feet had an increased risk of foot lesions. Increasing patient use of emollients may be key to preventing foot lesions.

Keywords: diabetes, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), foot lesions, prevention, multivariate modeling

Foot lesions are a serious complication of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). Furthermore, lesions are a well-recognized predisposing factor leading to lower extremity amputations.1 Educational guidelines recommend many foot-care behaviors believed to decrease the incidence of diabetic foot wounds.2 However, the literature lacks evidence-based recommendations about the most effective foot-care behaviors to prevent foot complications.3 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify specific patient behaviors independently associated with lower extremity lesions in patients with NIDDM.

METHODS

Patients (n= 295) diagnosed with NIDDM and receiving care in an urban academic general internal medicine practice were part of an intervention focused on patient education and physician reminders described in detail elsewhere.4 Trained nurse-clinicians conducted patient interviews and foot examinations at intake. The interviews included a detailed investigation of behavioral practices and an observation of how patients examined their feet. After 1 year, patients were again evaluated regarding foot-care behaviors and physical findings on their feet.

Table 1 contains the predictor variables measured during the study, categorized as self-foot care; self-foot examination, going barefoot, and other related behaviors. The most severe lesion on each foot was rated using the Seattle Wound Classification.5 For this study, the outcome variable was dichotomized. Wounds classified as greater than or equal to 1.2 (a superficial or healing minor lesion) were considered outcomes. Information regarding nonhealing and new lesions could not be accurately determined from the patient or medical record.

Table 1.

Univariate Models Associating Foot-Care Behaviors with Foot Lesions

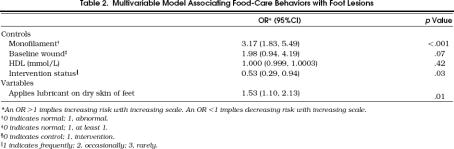

Data were analyzed using logistic regression techniques for correlated outcomes,6 to allow the use of foot-dependent (e.g., baseline wound) and foot-independent (e.g., smoking) covariates. Physiologic controls were included (Table 2) because previous studies have shown their importance.7 With these controls, univariate predictors with a p < .2 were considered candidates for the multivariate model developed using both forward and backward modeling procedures. Because of the large number of predictor variables compared with the small number of outcomes, a significance level of .01 was used to preclude overfitting the multivariate model. Model diagnostics included examination for two-way interactions, outliers, and collinearity.

Table 2.

Multivariable Model Associating Food-Care Behaviors with Foot Lesions

Because we expected behavioral changes due to the intervention, we also examined associations between incident foot lesions and the change in behaviors between baseline and follow-up to see if the intervention was masking a predictor's ability to enter the model. Using the same physiologic controls, this alternative model replaced intervention status with each behavior's “change score” that equaled follow-up behaviors minus baseline behaviors. This analysis followed the same techniques as previously explained.

RESULTS

Study participants were mainly African American (76%), elderly (mean age = 60.4 years), female (81%), with a low yearly income (77% with < $10,000 per year), and diagnosed with diabetes for a mean duration of 10 years. There were no significant differences in the patient characteristics between patients who completed the study (n = 253) and those who did not complete the study.4 At the follow-up assessment, 53 patients had 63 outcomes.

Table 1 contains the baseline prevalence of predictor variables and the results of the univariate analysis. Only six univariate predictors were candidates for the multivariate model. Forward and backward regression yielded the same multivariate model.Table 2 displays these results detailing the odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p values. Over the 1-year study period, patients who infrequently lubricated their feet had 3.1 times higher odds of having a foot lesion than those who frequently lubricated their feet. No two-way interactions were significant. The model examining changes in behaviors during the study period was identical to the reported model (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our study investigates the relative contribution of commonly cited preventative behaviors to identify the most crucial elements for focused patient education. We discovered that patients who rarely lubricate their feet had an increased risk of foot lesions. One explanation for this finding may be related neuropathic risk factors. Autonomic neuropathy has been associated with dry, cracked skin on the feet,8 and lubricating feet may improve symptoms of neuropathy, modifying patient's risk of developing foot lesions.

The control variables also provide insight into diabetic foot wounds. In particular, monofilament abnormalities were highly associated with foot wounds. If foot lubrication is considered a marker for autonomic neuropathy, then statistical independence between lubricating and monofilament testing suggests that autonomic and sensory neuropathy are both unique pathologic aspects of foot wounds of this severity. The insignificance of high density lipoprotein level (HDL) and baseline wounds as a predictor of foot wounds is similar to other findings with wounds of this severity.7 However, it is important to note that HDL abnormalities and baseline wounds have been shown to be predictors of more severely rated wounds.7

Our study also attempted to examine prospectively the contribution of visiting a podiatrist to the prevention of foot lesions. Despite a common belief that podiatric care is beneficial in preventing lower extremity complications, there are few data in the literature demonstrating an association between visits to podiatry and decreased foot lesions. Although visiting a podiatrist regularly was not an independent predictor of foot wounds, it was a candidate for the final model. Further research is needed to determine whether specific aspects of patient's podiatric utilization affect lower extremity complications in diabetic patients.

Limitations of this study include generalizability, as our study group included mainly minority patients who may be at increased risk of lower extremity lesions.9 Also, many of the variables were based on patient report; however, those data were complemented with nurse-clinicians' observations. Finally, our study measured wound status only at the beginning and end of the study period. We were unable to assess the occurrence and healing of wounds between visits.

Previous study has shown that patients believe information exchange with a physician is very important and physicians may underestimate the importance of their role in direct patient education.10 In a busy clinical practice, the education provided by a physician is sometimes necessarily brief and should contain at least the crucial elements most highly associated with beneficial outcomes. Our study indicates foot lubrication as one item for focused education. This is not to say that other foot-care behaviors are unimportant, and certainly further study is warranted. But in busy clinical settings, physicians may be able to focus their efforts and improve foot outcomes by simply educating patients about the importance of lubricating their feet.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by contract 200-08-0661 from the Division of Diabetes Translation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and by grant 22318 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References

- 1.Pecoraro RE, Reiber GE, Burgess EM. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation. Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:513–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foot care in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:S233–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiber GE, Edward JB, Smith DG. Lower extremity foot ulcers and amputations in diabetes. In: Harris MI, Cowie CC, Stern MP, Boyko EJ, Retber GE, editors. Diabetes in America. 2nd. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 1995. pp. 409–27. NIH publication 95-1468. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litzelman DK, Slemenda CW, Langefeld CD, et al. Reduction of lower extremity clinical abnormalities in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:36–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pecoraro RE, Reiber GE. Classification of wounds in diabetic amputees. Wound. 1990;2:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litzelman DK, Marriott DJ, Vinicor F. Independent physiologic predictors of foot lesions in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1273–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.8.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sims DS, Jr., Cavanagh PR, Ulbrecht JS. Risk factors in the diabetic foot. Recognition and management. Phys Ther. 1988;68:1887–902. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.12.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tull ES, Roseman JM. Diabetes in African Americans. In: Harris MI, Cowie CC, Stern MP, Boyko EJ, Retber GE, Bennett PH, editors. Diabetes in America. 2nd. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 1995. pp. 613–29. NIH publication 95-1468. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laine C, Davidoff F, Charles LE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients' and physicians' opinions. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:640–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]