Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To identify from the literature and clinical experience a rational approach to management of fibroadenomas of the breast.

METHOD

Recent literature on detection, diagnosis, and natural history of fibroadenomas was reviewed. Experience with over 4,000 women evaluated in the breast clinic at the Tel- Aviv Medical Center contributed to the management strategies suggested by review of the literature.

RESULTS

Fibroadenomas of the breast are common, accounting for 50% of all breast biopsies performed. Physical examination, sonography, and fine needle aspiration are effective in distinguishing fibroadenomas from breast cancer. Transformation from fibroadenoma to cancer is rare; regression or resolution is frequent, supporting conservative approaches to follow-up and management.

CONCLUSION

Age-based algorithms that allow for conservative management and that limit excision to patients whose fibroadenomas fail to regress are presented.

Keywords: fibroadenoma, breast neoplasms, women

Fibroadenomas are common benign lesions of the breast that usually present as a single breast mass in young women. They are assumed to be aberrations of normal breast development or the product of hyperplastic processes, rather than true neoplasms. The clinician often faces the dilemma whether to remove the mass or to monitor it by means of periodic follow-up examinations. Although removal of these lesions is a definitive solution, surgery may involve unnecessary excisions of benign lesions and unbecoming cosmesis. Moreover, a policy of conducting surgery on all patients with fibroadenomas would place an enormous burden on health care systems. A balanced and rational approach to the management of a fibroadenoma of the breast needs to address the crucial questions about its association with breast cancer, especially whether or not it is a marker of increased risk of breast malignancy. Another consideration to be weighed is that a substantial percentage of these lesions undergo spontaneous regression. Herein, based on our review of the current data on fibroadenomas of the breast and our experience, we propose practical algorithms for their management.

INCIDENCE AND RISK FACTORS

There are no clear-cut data on the incidence of fibroadenomas in the general population. In one study, the rate of occurrence of fibroadenomas in women who were examined in breast clinics was 7% to 13%,1 while it was 9% in another study of autopsies.2 Fibroadenomas comprise about 50% of all breast biopsies, and this rate rises to 75% for biopsies in women under the age of 20 years.3, 4 Fibroadenomas are more frequent among women in higher socioeconomic classes 5–7 and in dark-skinned populations.8 The age of menarche, the age of menopause, and hormonal therapy, including oral contraceptives, were shown not to alter the risk of these lesions.6, 7, 9, 10 Conversely, body mass index and the number of full-term pregnancies were found to have a negative correlation with the risk of fibroadenomas.5–7, 9, 11 Moreover, consumption of large quantities of vitamin C and cigarette smoking were found to be associated with reduced risk of a fibroadenoma.7, 12, 13

No genetics factors are known to alter the risk of fibroadenoma. However, a family history of breast cancer in first-degree relatives was reported by some investigators to be related with increased risk of developing these tumors.14, 15

PATHOLOGY

Fibroadenomas usually form during menarche (15 –25 years of age), a time at which lobular structures are added to the ductal system of the breast (Fig. 1). Hyperplastic lobules are common at that time, and may be regarded as a normal phase of breast development.16 Hyperplastic lobules were shown to be histologically identical with fibroadenomas.10, 17 Analyses of the cellular components of fibroadenomas by means of polymerase chain reaction demonstrated that both the stromal and the epithelial cells are polyclonal,18 supporting the theory that fibroadenomas are hyperplastic lesions associated with aberration of the normal maturation of the breast, rather than true neoplasms.16, 18

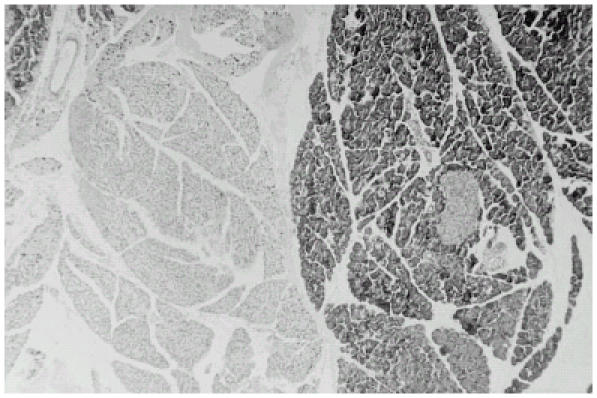

Figure 1.

Histologic section of a fibroadenoma (hematoxylin-eosin staining, × 40). The cellular fibroblastic stroma, which resembles intralobular stroma, encloses glandular and cystic spaces lined by epithelium. Round and oval gland spaces, lined by either single or multiple cell layers, are present in other areas. The stroma in the connective tissue appears to have undergone a more active proliferation with compression on the gland spaces.

The pattern of stromal growth in a fibroadenoma depends on its epithelial component: stromal mitotic activity was found to be higher near this component.19 Fibroadenomas are stimulated by estrogen and progesterone, and by lactation during pregnancy, and they undergo atrophic changes in menopause.16 Some fibroadenomas have receptors and respond to growth hormone and epidermal growth factor.20

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

A fibroadenoma is most often detected incidentally during a medical examination or during self examination, usually as a discrete solitary breast mass of 1 to 2 cm.15, 21 Although they can be located anywhere in the breast, the majority are situated in the upper outer quadrant.22 A fibroadenoma is usually smooth, mobile, nontender, and rubbery in consistency (Fig. 2). Several other breast lesions have similar characteristics, and physical examinations provided an accurate diagnosis in only one half to two thirds of cases studied.23, 24 However, most of the masses that are erroneously diagnosed by palpation as fibroadenomas are found on histologic examination to be another benign form of breast disease,25 such as cystic fibrosis.

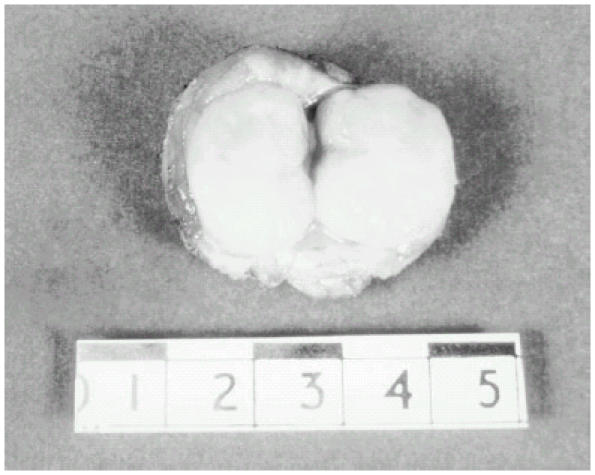

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearance of a fibroadenoma. The spherical mass is sharply circumscribed, and could be easily separated from the surrounding breast tissue. The section margins have a green-white color, and contain slit-like spaces.

Multiple Fibroadenomas

From 10% to 16% of patients with multiple fibroadenomas have two to four in a single breast, which may present initially or be discovered over several years.15, 22 Unlike women with a single fibroadenoma, most of the patients with multiple fibroadenomas have a strong family history of these tumors.26 A possible connection between multiple fibroadenomas and oral contraceptives was proposed but has not yet been substantiated.27

Giant and Juvenile Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas larger than 5 cm (about 4% of the total) are commonly defined as being giant fibroadenomas;21 however, this terminology is not universally accepted. Giant fibroadenomas are usually encountered in pregnant or lactating women. When found in an adolescent girl, the term juvenile fibroadenoma is more appropriate.15 These lesions in young women constitute 0.5% to 2% of all fibroadenomas, and are rapidly growing masses that cause asymmetry of the breast, distortion of the overlying skin, and stretching of the nipple. Histologically, they appear to be more cellular and have less lobular components than do simple fibroadenomas. However, giant fibroadenomas are benign lesions that do not undergo transformation into malignancy.28

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Sonography

Breast sonography is often used for the diagnosis of fibroadenomas. The sonographic criteria that support the diagnosis of a fibroadenoma are a round or oval solid mass with a smooth contour and weak internal echoes in a uniform distribution and intermediate acoustic attenuation 29 (Fig. 3). This imaging technique is very useful for differentiating between solid and cystic lesions. However, attempts to correlate between the sonographic features of solid masses compatible with fibroadenomas and pathologic findings were disappointing.30 There is some overlap in the sonographic criteria for fibroadenomas and for breast cancer,31 and approximately 25% of fibroadenomas appear with irregular margins, which may imply that the lesions are malignant.29 Also, only 82% of biopsy-proven fibroadenomas were visualized by sonography in one study.29

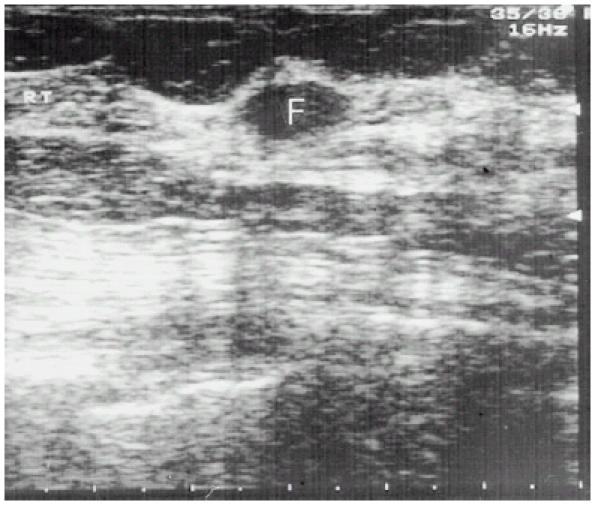

Figure 3.

Sonographic appearance of a fibroadenoma. The mass is homogenous, with sharp and smooth margins. Slight posterior and edge enhancements are visible. Neither compression effects nor internal echoes are present.

Mammography

The yield of mammography in young women is low, and its role in the diagnosis of fibroadenomas is limited. However, it may disclose features of infiltrative lesions in older women. In the mammographic image, fibroadenomas appear as soft, homogenous, and well-circumscribed nodules, and inner coarse calcifications are often observed.

ASPIRATION CYTOLOGY

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) has become a popular method in the evaluation of breast masses. The characteristic cytologic features of fibroadenomas are: clusters of spindle cells without inflammatory or fat cells, found in 96% of all fibroadenomas; aggregates of cells with a papillary configuration resembling elk antler (antler horn clusters), found in 93% of all cases; and uniform cells with well-defined cytoplasm lying in rows and columns (honeycomb sheets), found in 95% of all fibroadenomas.32 Taken together with the clinical diagnosis of fibroadenoma, FNA can improve the sensitivity of the diagnosis to 86% with a specificity of 76%,21, 30 while for breast cancer FNA is 96% sensitive and 98% specific. Thus, while aspiration cytology may confuse fibroadenomas with other benign breast lesions, incorrect diagnosis of a malignant process is rare.

The overall diagnostic efficacy of these three modalities—namely, manual breast examination, imaging and cytology is approximately 70% to 80%, but they provide a 95% (±2% SD) accurate differentiation between a benign and a malignant lesion. A follow-up period of 1 to 3 years after fibroadenoma is diagnosed and breast cancer is excluded using the three modalities can enhance the accuracy of the diagnosis.33, 34

FIBROADENOMA AND BREAST CANCER

Any analysis of the associations of fibroadenomas with breast cancer must address two main questions: whether or not a fibroadenoma is a marker for increased risk of breast cancer, and whether or not breast cancer can evolve from the epithelial component of a fibroadenoma. The first issue was originally assessed in several retrospective studies,14, 35–41 which demonstrated a 1.3 to 2.1 increased risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenomas compared with the general population. The elevated risk was persistent, and did not decrease with time. A more recent study designed to delineate the possible correlation between the histologic features of the fibroadenomas and the risk for subsequent breast cancer used the term “complex fibroadenoma.”15 This term applies to fibroadenomas having the histologic characteristic of being more than 3 mm in diameter, or with elements of sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcifications, or papillary apocrine metaplasia, which were associated with a 3.1 elevated risk of breast cancer. Proliferative changes in the parenchyma adjacent to the fibroadenoma were related to a further increase of the risk to 3.88. The relative risk for women with a familial history of breast cancer and complex fibroadenoma was 3.72, compared with control women with a family history of breast cancer without fibroadenoma. In these studies, women with noncomplex fibroadenomas and no family history of breast cancer were not at a greater risk of breast cancer.

Malignant transformations in the epithelial components of fibroadenomas are generally considered rare. The incidence of a carcinoma evolving within a fibroadenoma was reported to be 0.002% to 0.0125%.42, 43 About 50% of these tumors were lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), 20% were infiltrating lobular carcinoma, 20% were ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and the remaining 10% were infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The clinical, sonographic and mammographic findings are usually similar to those of benign fibroadenomas,44, 45 and the malignant changes are often noted only when the fibroadenoma is excised.

In a clinicopathologic study of 105 women with carcinoma developing within fibroadenomas, the mean age was higher than in patients with benign fibroadenomas (44 vs 23 years).33, 34, 46 However, in that study, DCIS and LCIS in equal frequencies comprised 95% of the cases, and carcinoma in situ was also present in the adjacent breast tissue in about 20% of these women. No axillary metastases were found in any of the study patients.

NATURAL HISTORY

There are inherent obstacles in studying the natural course of breast fibroadenomas, and the data are not unequivocal. Some investigators believe that most fibroadenomas grow over a 12-month period to gain a size of 2 to 3 cm, after which they remain unchanged for several years.15 As definite diagnosis can be obtained only from histologic sections, solitary solid masses usually have been excised, and long term follow-up surveys are limited in number. These studies followed young women for up to 29 years, and regression or complete resolution of the fibroadenomas were noted in 16% to 59% of all cases.21, 23, 46, 47 It was extrapolated that the probability that a fibroadenoma would resolve after 5 years is approximately 50%, and the “lifetime” of a fibroadenoma is about 15 years.34 Among the 50% of fibroadenomas that did not regress spontaneously, about half did not change, and the remaining 25% enlarged in size during the follow-up.21

From their incidence in mastectomy specimens, it has been assumed that fibroadenomas tend to regress and loss their cellularity with age. The rare finding of fibroadenomas in the older age groups also supports the hypothesis of regression of fibroadenomas.48 The mechanisms offered to explain the regression of fibroadenomas are infarction, calcification, and hyalinization.15, 49

TREATMENT

As fibroadenomas are benign breast lesions, it could be argued that they should not be excised and can be expected to regress spontaneously. Moreover, 30% of breast tumors that are diagnosed as fibroadenomas are found postsurgically to be other types of benign lesions. In Cant et al.'s follow-up studies on clinically diagnosed fibroadenomas, persistent lesions were excised after 3 years: fibroadenomas were found in the histologic examinations of 97% of these cases.33, 34 These findings suggest that the other benign lesions had resolved spontaneously during 1 to 3 years, that the remaining masses were true fibroadenomas, and that conservative management is warranted. Not all women can be candidates for conservative treatment: the patient's age, a family history of malignancy, and any data on proliferative changes in the breasts from previous biopsies must be taken into consideration.

The risk of missing breast cancer in women under 25 years of age who have fibroadenomas as diagnosed by physical examination, sonography, and FNA is 1 in 229 to 1 in 700.21, 24 This risk remains very low in women under the age of 35 years. Therefore, it has been recommended that young patients should be observed with frequent clinical evaluations, and the lesions excised in women over the age of 35 years.22, 23, 30 Other investigators suggested that the cutoff age should be 25 years.33

The preferred management of multiple fibroadenomas is complete excision. However, this approach can lead to undesirable scarring or to extensive ductal damage if all the fibroadenomas are excised through one incision.26, 50 Giant fibroadenomas tend to shrink after cessation of lactation, so their removal should be delayed until the patient's hormonal status returns to normal, and a smaller excision can be performed.15, 21 It may be very disfiguring to excise juvenile fibroadenomas because of their large sizes; nevertheless, no recurrences were reported after complete excision, and normal and symmetrical development of the breasts can be anticipated.28, 51

MANAGEMENT

In our breast clinic at the Tel-Aviv Medical Center, more than 4,000 women are examined each year. From experience, we believe that if conservative management of fibroadenoma is to be advocated, physical examination, sonography, and FNA should all be performed, and their results should be compatible with fibroadenoma. In women older than 35 years, mammography should also be carried out. Because of the increased incidence of carcinoma in older women, we recommend two different treatment approaches for fibroadenomas in women younger and older than 35.

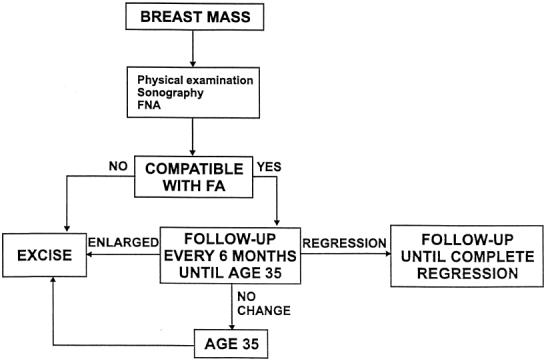

For women in which a fibroadenoma is diagnosed before the age of 35, we recommend conservative management with a protocol of follow-up every 6 months in order to detect any changes of the lesion (Fig. 4). In cases of regression, the follow-up should continue until complete regression. Fibroadenomas that either do not completely regress, or remain unchanged by the age of 35, should be excised surgically. Fibroadenomas that become larger should be excised without delay. In patients with a family history of breast cancer, or known changes of complex fibroadenoma, we recommend excisional biopsy shortly after diagnosis has been established.

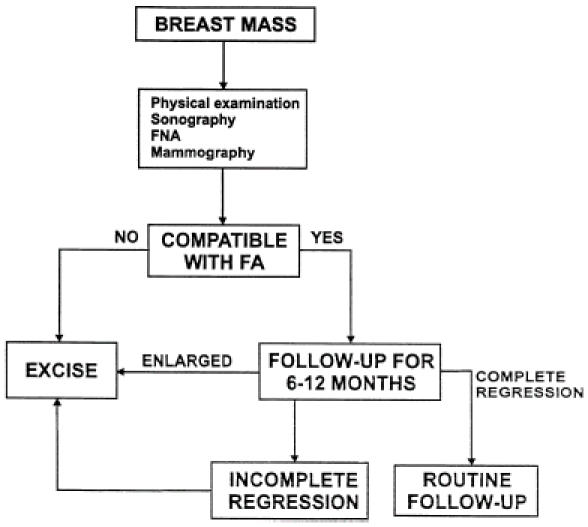

Figure 4.

Management of a fibroadenoma (FA) in women younger than 35 years of age.

When a fibroadenoma is detected in a woman older than 35 years of age, and all the findings of the above-mentioned diagnostic modalities (including mammography) support this diagnosis, a short follow-up period of 6-12 months is justified because other benign changes may resolve and an operation can be obviated (Fig. 5). After 12 months, any persistent fibroadenoma should be excised.

Figure 5.

Management of a fibroadenoma (FA) in women older than 35 years of age.

Our experience, and that reported by others,52 is that when offered the option of conservative management, most women will eventually prefer excisional biopsy. Our recommendation is to treat a woman with multiple fibroadenomas in the same manner as a woman with a single lesion. Physical examination, ultrasound, and FNA should be done, and if a diagnosis of multiple fibroadenoma can be made with confidence, conservative treatment with follow-up every 6 months should be recommended. Excisional biopsy is advised for any mass for which the diagnosis is not clear-cut.

References

- 1.Dent DM, Hacking EA, Wilkie W. Benign breast disease clinical classification and disease distribution. Br J Clin Pract. 1988;42(suppl 56):69–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franyz VK, Pickern JW, Melcher GW, Auchincoloss JR. Incidence of chronic cystic disease in so-called normal breast: a study based on 225 post mortem examinations. Cancer. 1951;4:762–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195107)4:4<762::aid-cncr2820040414>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuerch C, Rosen PP, Hirota T, Itabashi M. A pathologic study of benign breast disease in Tokyo and New York. Cancer. 1982;50:1899–902. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821101)50:9<1899::aid-cncr2820500942>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onuigb WIB. Adolescent mass in Nigerian igbos. Am J Surg. 1979;137:367–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinton LA, Vajsey MP, Flavel R. Risk factors for benign breast disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113:203–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soini I, Aine R, Lauslthti K. Independent risk factor of benign and malignant breast lesion. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;114:507–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu H, Rohan TE, Cook MG, Howe GR. Risk factor for fibroadenoma: a case control study in Australia. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:247–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funder Burk WW, Rosero E, Leffall LD. Breast lesions in blacks. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;135:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravnihar B, Segel DG, Lindther J. An epidemiologic study of breast cancer and benign breast neoplasm in relation to the oral contraceptive and estrogen use. Eur J Cancer. 1979;15:395–405. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(79)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canny PF, Berkowitz GS, Kelsey JL. Fibroadenoma and the use of exogenous hormones: a case control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:454–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Franceshi S. Risk factors for pathologically confirmed benign breast disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:115–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkowitz GS, Canny PF, Vivolsy VA. Cigarette smoking and benign breast disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39:308–13. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohan TE, Cook MG, Potter JD. A case control study of diet and benign proliferative epithelial disorder of the breast. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3176–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupont WD, Page DL, Park FF. Long-term risk for breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:10–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407073310103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haagensen CD. Disease of the breast. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders; 1996. 267–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes LE, Mansel RE, Webster DJT. Aberration of normal development and involution: a new perspective on pathogenesis and nomenclature of benign breast disorders. Lancet. 1987;11:1316–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parks AG. The micro anatomy of the breast. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1959;25:235–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noquchi S, Motomura K, Inaji H, Imorka S. Clonal analysis of fibroadenoma and phylloides tumor of the breast. Cancer Res. 1993;53(17):4071–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawhney N, Garrahan N, Douglas Jones AG, Williams ED. Epithelial stromal interaction in tumors: a morphologic study of fibroepithelial tumors of the breast. Cancer. 1992;70(8):2115–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2115::aid-cncr2820700818>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Agthoven T, Timmerans M, Foekens JA, Dorssers LC. Differential expression of estrogen, progesterone and epidermal growth factor receptors in normal, benign and malignant human breast tissues using dual staining immunohistochemistry. Am J Pathol. 1994;144(6):1238–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dent DM, Cant PJ. Fibroadenoma. World J Surg. 1989;13:706–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01658418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster ME, Garrahan N, Williams S. Fibroadenoma of the breast: a clinical and pathological study. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1988;33:13–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson S, Anderson TJ, Rifkind E, Chetty U. Fibroadenoma of the breast: a follow up of conservative management. Br J Surg. 1989;76:390–1. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cant PJ, Learmonth GM, Dent DM. When can fibroadenoma be managed conservatively. Br J Clin Pract. 1988;42(suppl 56):62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carty NS, Carter C, Rubin C, Ravichandran D. Management of fibroadenoma of the breast. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:127–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson ME, Lyons K, Hyghes LE. Multiple fibroadenoma of the breast a problem of uncertain incidence and management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:161–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregg WI. Gallactorrhea after contraceptive hormones. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:1432–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196606232742510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pike AM, Oberman HA. Juvenile cellular adenofibromas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:730–5. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cale Beuglet C, Soriano RZ, Kurtz AB, Goldberg BB. Fibroadenoma of the breast sonomammography correlated with pathology in 122 patients. AJR. 1983;140:369–75. doi: 10.2214/ajr.140.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson S, Forrest APN. Fibroadenoma of the breast. Br J Surg. 1985;72:835–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson VP, Rothschild PA, Kreipke DL, Mal TJ. The spectrum of sonographic finding of fibroadenoma of the breast. Invest Radiol. 1986;21:34–9. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bottels K, Chan JS, Holly EA. Cytologic criteria for fibroadenoma: a step wise logistic regression analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:707–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/89.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cant PJ, Madden MV, Close PM, Learmonth GM. Case for conservative management of selected fibroadenoma of the breast. Br J Surg. 1987;74:857–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cant PJ, Madden MV, Coleman MG, Dent DM. Nonoperative management of breast mass diagnosed as fibroadenoma. Br J Surg. 1995;82:792–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupont W, Parl FF, Hartman WH. Breast cancer associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 1993;71:125–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930215)71:4<1258::aid-cncr2820710415>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:146–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchinson WB, Thomas DB, Hamlin WB, Roth GJ. Risk of breast cancer in women with benign breast disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;65:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moskowits M, Gartside P, Wirman JA, McLaughlin C. Proliferative disorder of the breast as risk factors for breast cancer in a self-selected screened population. Radiology. 1980;134:289–91. doi: 10.1148/radiology.134.2.7352201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter CL, Corle DK, Micozzi MS, Schatzkin A, Tailor PR. A prospective study of the development of breast cancer in 16,692 women with benign breast disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:467–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDivitt RW, Stevens JA, Lee MC, Wingo PA. Histologic types of benign breast disease and the risk for breast cancer. Cancer. 1992;69:1408–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920315)69:6<1408::aid-cncr2820690617>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krieger N, Hiatt RA. Risk of breast cancer after benign breast diseases: variation by histologic type, degree of atypia, age at biopsy, and length of follow up. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:619–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deschenes L, Jacob S, Fobia J, Christen A. Beware of breast fibroadenoma in middle aged women. Can J Surg. 1985;28:372–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazanowski Konarky K, Harrison EG, Payne WS. Lobular carcinoma arising fibroadenoma of the breast. Cancer. 1975;35:450–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197502)35:2<450::aid-cncr2820350223>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pick PW, Iossifide IA. Occurrence of breast carcinomas within a fibroadenoma: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:590–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oyyello L, Gump PE. The management of patients with carcinomas in fibroadenomatous tumors of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz NM, Palmer JO, McDivitt RW. Carcinoma arising within fibroadenoma of the breast: a clinicopathological study of 105 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:614–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/95.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smallwood JA, Roberts A, Guyer DP, Taylor I. The natural history of fibroadenoma. Br J Clin Pract. 1988;56(suppl):86–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sainsbury JRL, Nicholson S, Needham GK, Wadehra V. Natural history of benign breast lumps. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1080–2. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800751110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerm WH, Clark RW. Retrogression of fibroadenoma of the breast. Am J Surg. 1973;126:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(73)80095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naraynsingh V, Raju GC. Familial bilateral fibroadenoma of the breast. Postgrad Med J. 1985;64:430–40. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.715.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mies C, Rosen PP. Juvenile fibroadenoma with atypical epithelium. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:184–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dixon JM, Dobie V, Lamb J, et al. Assessment of the acceptability of conservative management fibroadenoma of the breast. Br J Surg. 1996;83:264–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]