Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine primary care physicians' awareness of, and screening practices for, alcohol use disorders (AUDs) among older patients.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional telephone survey of a national sample of primary care physicians.

PARTICIPANTS

Physicians randomly sampled from the Masterfile database of the American Medical Association and stratified by specialty as family practice physicians, internal medicine physicians, and either family practice or internal medicine physicians with geriatric certification.

MAIN RESULTS

A total of 171 physicians were contacted: 155 (91%) agreed to participate, and responses were analyzed from 150 (50 family practice, 50 internal medicine, 50 with geriatric certification). The median prevalence estimate of AUDs among older patients was 5% for each group of physicians. In contrast to published prevalence rates of AUDs ranging from 5% to 23%, 38% of physicians reported prevalence estimates of less than 5%, and 5% cited estimates of at least 25%. Compared with the other groups, the physicians with geriatric certification were more likely to report no regular screening (42% vs 20% for family practice vs 18% for internal medicine, p=.01), while younger (<40 years) and middle-aged physicians (40–55 years) reported higher annual screening rates relative to older physicians (>55 years) (77% vs 60% vs 44% respectively, p=.03). Among physicians who regularly screened (n=110), 100% asked quantity-frequency questions, 39% also used the CAGE questions, and 15% also cited use of biochemical markers.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary care physicians may “underdetect” AUDs among older patients. The development of age-specific screening methods and physician education may facilitate detection of older patients with (or at risk for) these disorders.

Keywords: alcohol use disorders, older patients, screening

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are widely regarded as one of the nation's most important public health problems.1–3 These disorders are heterogeneous and include alcohol abuse or dependence disorders,4 as well as less severe drinking problems, often referred to as heavy, hazardous or harmful drinking.5, 6 Although well known as disorders that affect young and middle-aged adults, previous studies suggest that AUDs are also common among older adults.7–18 Prevalence estimates for alcohol abuse or dependence range from 8% to 21% among older hospitalized patients.7–9 In outpatient health care settings, prevalence rates for any AUD range from 5% to 23% in older ambulatory patients.10–18

Despite the substantial prevalence, physicians often fail to detect AUDs in older populations. In prior studies, physicians detected only 30% of older hospitalized patients with active drinking disorders,19 and fewer than 25% of older emergency department patients with current alcohol problems.20 Factors that may contribute to underrecognition of AUDs include nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms (e.g., neglect, incontinence, or malnutrition) associated with AUDs in older adults, lack of physician awareness about the extent of the problem, physician reluctance to obtain histories of alcohol use from older patients, and lack of age-specific screening instruments that could facilitate detection among the elderly.

Recognition of AUDs in older adults is important, particularly in primary care settings, because effective treatments are available and can be safely administered on an outpatient basis.21, 22 The extent to which primary care physicians recognize alcohol problems among older adults and screen for these disorders has not been previously examined. Accordingly, we conducted a nationwide telephone survey of primary care physicians to determine physicians' awareness of, and screening practices for, AUDs in older patients, and to describe the spectrum of AUDs encountered by physicians in this patient population.

METHODS

Sample

A list of U.S. physicians was obtained from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physicians' Masterfile database. This database provides demographic information on both AMA and non-AMA members and is published in text form as the Directory of Physicians in the United States. Eligible subjects were physicians whose practice code designation was listed as direct patient care and whose medical specialty designation was family practice (FP), internal medicine (IM), or family practice or internal medicine with geriatric certification (FPG/IMG). We excluded from the sample physicians working abroad or in any of the armed services.

Our plan was to collect data from 50 physicians in each group (n= 150). To achieve this goal, we used a table of random numbers to eventually select the names and addresses of 254 physicians listed in the AMA's Directory. Because physicians' telephone numbers are not published in the registry, we contacted local directory telephone assistance and conducted Internet searches of the GTE Super Pages. For 72 (28%) of the 254 sampled physicians, corresponding telephone numbers could not be identified, and no further attempts were made to locate these potential participants. The offices of all sampled physicians with available telephone numbers (n= 182) were subsequently contacted by telephone to confirm physicians' mailing addresses and their practice status. After excluding 4 physicians (2%) who had either retired or died, and 7 (4%) who had moved, the remaining 171 physicians (94%) were eligible participants.

Survey Procedure and Questionnaire

All physicians (n= 171) with a verified address and telephone number received an invitation letter describing the study's purpose and stating that the telephone questionnaire would take no more than 5 minutes to complete. Prospective physicians received a telephone call 2 weeks, on average, after each invitation letter was mailed.

To ascertain physicians' prevalence estimates for AUDs, we asked participants to estimate the proportion of patients aged 65 years and older with “drinking problems.” As we sought to determine physicians' prevalence estimates for all AUDs (not only alcohol abuse or dependence per se), we did not routinely provide definitions for “drinking problems.” Eighteen participants (11%) prefaced their responses by asking what we meant by drinking problems; we informed them that we were interested in knowing the proportion of their older patients who were currently experiencing (or were at risk for) adverse physical, social, or psychological consequences from alcohol use.

We asked physicians to describe the types of drinking problems they encountered among older patients, and we then coded the open-ended responses. To determine the frequency of screening, we asked “Do you regularly screen for drinking problems in your older patients?” Physicians who answered “yes” to this item were asked what methods they used, and how often the individual screening methods were applied. For physicians who answered “no,” we asked why they did not screen. We also inquired about physicians' demographic and practice characteristics. Appendix A shows the questions used in the telephone survey.

Analytic Methods

The univariate distributions of all variables were initially inspected for coding errors and maldistributions. Group differences in demographic and practice characteristics were appraised using χ2or Fisher's Exact tests for categorical variables, and Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance tests for dimensional variables. Two-tailed p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. EPI-INFO was used for data entry, and both EPI-INFO and SAS programs were used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 171 physicians contacted by telephone, 155 (91%) agreed to participate, and 150 were included in the study. Reasons for nonparticipation (n= 16) were as follows: seven physicians were too busy, three did not participate in telephone surveys, and a time to conduct the interview could not be identified for six practitioners. We excluded five physicians: one who reported that he had assumed an administrative position before the interview began, and four after the interviews were completed (one participant was working as an occupational physician, and three were full-time directors of nursing homes). Because we wanted to focus on primary care activities, these physicians were deemed ineligible and subsequently removed. Overall participation rates were 90%, 90%, and 88%, respectively, for the FP, IM, and FPG/IMG groups; the latter group comprised 16 FP and 34 IM physicians.

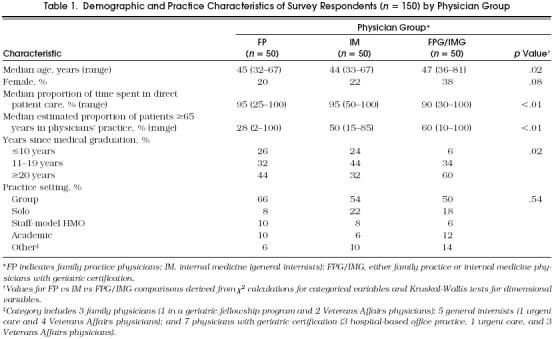

Compared with FP and IM participants, FPG/IMG physicians were older, more likely to be female, and spent slightly less time proportionately each week providing direct patient care (Table 1) Most physicians (57%) practiced in a group setting, whereas 16% were solo practitioners, 8% worked in staff-model HMOs, 9% were academic-based physicians, and 10% practiced in other settings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Practice Characteristics of Survey Respondents (n= 150) by Physician Group

Almost all physicians (96%) reported caring for some older patients with AUDs, with a median estimate of 5% for each physician group. Overall 38% of physicians judged the prevalence of AUDs to be 4% or less among older patients, whereas 5% reported prevalence estimates of at least 25% (Table 2 In data not shown, physician age, gender, years since medical graduation, and the proportion of older adults in a practice were not associated with physicians' prevalence estimates. Physicians working in the Department of Veterans Affairs (n= 9) reported significantly higher median prevalence estimates than did physicians in all other practice settings (n= 141) (15% vs 5%, p= .03). In addition, 29 (19%) of the physicians qualified their prevalence estimates with statements such as, “[X] percent of my older patients have alcohol problems—at least that I'm aware of,” indicating their reported estimates most likely underestimated the true prevalence of AUDs in their respective practices.

Table 2.

Physicians' Prevalence Estimates for Alcohol Use Disorders Among Older Patients

Physicians reported at least four distinctive types of AUDs: 106 (71%) of the physicians stated that they cared for older patients with chronic alcohol abuse or dependence, 55 (37%) reported harmful or heavy alcohol use, 35 (23%) encountered late-onset drinking disorders, and 6 (4%) reported binge drinking problems in this patient population.

A significant minority (27%) indicated that they did not screen older patients for alcohol problems on a regular basis (Table 3) The proportion of physicians who did not regularly screen varied significantly from 20% to 18% to 42% (p= .01) among FP, IM, and FPG/IMG physicians, respectively. The following reasons were mentioned by the 40 physicians who did not screen routinely: no time (12), screening not part of routine practice (10), condition not prevalent enough to warrant screening (7), older patients reluctant to answer questions about alcohol use (5), used clinical judgment instead of routine screening methods (5), and futility of treatment interventions (1).

Table 3.

Screening Practices for Alcohol Use Disorders in Older Patients

A total of 110 physicians (73%) reported regular screening for AUDs, and 93 (62%) screened at least annually (Table 3). Annual screening rates ranged from 66% to 68% to 52% (p= .20) for FP, IM, and FPG/IMG physicians, respectively.

We examined physician age, gender, years since medical graduation, practice setting, and proportion of patients in practice aged 65 years and older as factors potentially associated with an increased likelihood of screening for AUDs on an annual basis. Of these variables, only age was associated with frequency of screening: annual self-reported screening rates varied from 77% to 60% to 44% (p= .03) for young (<40 years), middle-aged (40–55 years), and older physicians (>55 years), respectively. In multivariate cross-stratification analyses (data not shown), the prevalence of self-reported screening was lowest (30%) among older geriatric physicians.

Among physicians who regularly screened for AUDs (n= 110), all reported asking standard quantity-frequency questions. Other screening methods, such as the CAGE questions, were reportedly used by 40%, 29%, and 52% of FP, IM, and FPG/IMG practitioners, respectively (p = .16). Across the three groups, biochemical markers such as the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and hepatic transaminases were used as screening tools by 13%, 17%, and 14% of FP, IM, and FPG/IMG physicians, respectively. Finally, one family physician and one general internist with geriatric certification reported use of the recently developed Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT).

DISCUSSION

We found associations between self-reported screening rates for AUDs and physician specialty and age. Physicians with geriatric training and those aged 55 years or older were less likely to screen their older patients for AUDs. Although surveyed geriatricians may have obtained more training in the area of alcohol problems in the elderly, our results suggest that this training (if received) did not result in any favorable change in behavior. Our results also suggest that younger cohorts of physicians are more likely to screen older patients for AUDs. We do not know whether the observed differences are due to recent changes in medical education or perhaps reflect the recent emphasis on the detection of AUDs in primary care settings.2 Further studies are therefore needed to determine whether positive secular trends are present with respect to physicians' screening and treatment practices for AUDs in this patient population.

In our survey, reported prevalence estimates of AUDs among older patients varied widely (0%–50%), although the median prevalence estimates (5%) and corresponding distributions of AUDs did not vary among the three physician groups. Of concern, however, was the finding that approximately 40% of physicians reported AUD prevalence rates of 4% or less in their respective practices.

At least nine studies have examined the prevalence of AUDs among older outpatients.10–18 Eight investigations reported prevalence estimates of 5% to 23% for alcohol abuse or dependence.11–18 A single study examined the prevalence of heavy drinking in an older outpatient population by screening more than 5,000 primary care patients aged 60 years and above, and found that 15% of men and 12% of women were heavy drinkers (defined as>14 drinks per week for men and>7 drinks per week for women).10

Although physicians may have accurately reported actual prevalence rates of AUDs in their respective practices, we suspect that underdetection of AUDs may be occurring among older patients. This inference is based on comparisons of physicians' reported estimates with published rates of AUDs.10–18 It is important to note that published prevalence data (with the exception of one study)10 are for alcohol abuse or dependence only. The combined prevalence of all AUDs among older outpatients, including not only alcohol abuse and dependence, but also heavy, hazardous, and harmful drinking, is likely to be significantly greater than published estimates for abuse or dependence alone.

Several possible reasons may contribute to underdetection in this population of patients. Failure to screen for AUDs in older patients could lead to underdetection. The majority (73%) of physicians in our study, however, reported screening older patients regularly. Although it is possible that physicians' reported screening practices do not correspond to their actual practice patterns, our results suggest that infrequent screening may not contribute substantially to underdetection.

The use of inadequate screening methods may also result in underdetection among older patients. Standard quantity-frequency questions were used by all physicians who reported regular screening, but may not be the optimum screening questions in this population for several reasons. First, this approach relies on subjects' estimating an average frequency and volume of consumption and ignores the distinctive patterns in which alcohol may be consumed (e.g., binge drinking vs one glass of wine with meals each day). Second, a risk gradient may be difficult to identify in older adults using this approach: for older adults with significant comorbid illness and on multiple medications, even low volumes of alcohol may cause adverse health outcomes.23 Finally, this screening approach measures current and not cumulative exposure. For many older adults, cumulative alcohol consumption, as opposed to current consumption, may be a more important determinant of alcohol-related risk.24

Approximately 40% of physicians also reported use of the CAGE questionnaire.25 Current standardized instruments, such as the CAGE or the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST),26 may not be the best screening tools in older populations for several reasons. First, the instruments target alcohol abuse or dependent drinkers. Heavy alcohol use may occur commonly in older populations but is not detected by these instruments.10 Second, the instruments do not provide information about the pattern of a patient's alcohol use. Many older adults may sustain adverse effects from alcohol yet drink in ways that would not be considered diagnostic for alcohol abuse or dependence. Third, neither test discriminates between current and past drinking problems (i.e., many questions are phrased, “Have you ever had a problem …?”) and could, if used alone, result in misclassification. Finally, these questionnaires were developed and standardized in studies of young adult males,27 and contain questions that focus on social impairment (e.g., “Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?” or “Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?”). These items may lack relevance for many older persons who no longer have paid employment or who live alone.

Elderly-specific screening instruments may facilitate the identification of older adults with AUDs. The recently developed geriatric version of MAST, called (MAST-G),28 is an age-specific method for detecting older persons with alcohol abuse or dependence. The MAST-G contains 24 questions that inquire about older persons' drinking behavior and their perceptions of adverse consequences, or personal concerns, which stem from alcohol use. Like the CAGE and the MAST, however, the MAST-G does not discriminate between current and past problem drinking, and seeks to detect older persons with alcohol abuse or dependence. One study found that the instrument performed similarly to the CAGE in identifying older veterans with alcohol abuse or dependence.11 Other studies are therefore needed to determine the MAST-G's ability to correctly identify older adults who experience problems from alcohol, but who are not dependent on it.

Fifteen percent of physicians in our study reported use of biochemical markers as screening tools. Although laboratory tests such as the MCV or hepatic transaminases may be helpful to monitor change in patients whose initial tests are positive, these tests have not been formally evaluated as screening tools for AUDs in older populations. Biochemical markers have limited sensitivity in detecting younger adults with AUDs,29, 30 and are likely to have limited performance in older populations as well.

Patient-mediated factors, such as older patients' reluctance to provide accurate alcohol histories, could also contribute to underdetection. A significant minority of physicians (19%) qualified their prevalence estimates for AUDs by stating, “[X] percent of my older patients have alcohol disorders—at least that I'm aware of.” These disclaimers suggest that many physicians felt that AUDs were underdetected in their respective practices. Although it would have been interesting to explore physicians' perceived barriers to assessing older patients for alcohol problems, e.g., denial on the part of the patient or the patient's family, we focused on the cited topics to keep the survey brief and enhance participation.

In conclusion, our results indicate that primary care physicians routinely encounter older patients with AUDs, but these disorders may be underdetected. The development of elderly-specific screening instruments and physician education may facilitate the identification of older patients who are currently experiencing, or are at risk for, alcohol problems. Further studies are needed to define physicians' perceived barriers to screening, diagnosis, and treatment of AUDs in older populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott Sherman, MD, MPH, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

Appendix A

Table 4.

Questions Used in Telephone Survey

References

- 1.Institute for Health Policy, Brandeis University . Substance Abuse: The Nation's Number One Health Problem: Key Indicators for Policy. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Taskforce . Screening for problem drinking. In: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The Physicians' Guide to Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office NIH publication; 1995. pp. 95–3769. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis JR, Geller G, Stokes EJ, Levine DM, Moore RD. Characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of alcoholism in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:310–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangion DM, Platt JS, Syam V. Alcohol and acute medical admission of elderly people. Age Ageing. 1992;21:362–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/21.5.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon A, Epstein LJ, Reynolds L. Alcoholism in the geriatric mentally ill. Geriatrics. 1968;23(10):125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams WL, Fleming M, Barry KL, Fleming M. Screening for problem drinking in older primary care patients. JAMA. 1996;276:1964–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morton JL, Jones TV, Manganaro MA. Performance of alcoholism screening questionnaires in elderly veterans. Am J Med. 1996;101:153–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)80069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan CM, Tierney WM. Health services use and mortality among older primary care patients with alcoholism. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1378–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacNeil PD, Campbell JW, Vernon L. Screening for alcoholism in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:SA7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones TV, Lindsey BA, Yount P, Soltys R, Farani-Enayat B. Alcoholism screening questionnaires: are they valid in elderly medical outpatients? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:674–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02598284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulop G, Reinhardt J, Strain JJ. Identification of alcoholism and depression in a geriatric medicine outpatient clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:737–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Welsh J, Centor RM, Schnoll SH. Screening for drinking disorders in the elderly using the CAGE questionnaire. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:662–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magruder-Habib K, Saltz CC, Barron PM. Age-related patterns of alcoholism among veterans in ambulatory care. Hosp Comm Psych. 1986;37:1251–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.12.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran MB, Naughton BJ, Hughes SL. Screening elderly veterans for alcoholism. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:361–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik PC, Jones RG. Alcohol histories taken from elderly people on admission. BMJ. 1994;308:248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6923.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams WL, Magruder-Habib K, Trued S, Bromme HL. Alcohol abuse in elderly emergency department patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1236–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilk AI, Jensen NM, Havighurst TC. Meta-analysis of randomized control trials addressing brief interventions in heavy alcohol drinkers. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:274–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers: a randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277:1039–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams WL. Potential for adverse drug-alcohol interactions among retirement community residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1021–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanwan N, Damesyn M, Reuben D, Greendal G, Moore A. Lifetime alcohol use and alcohol-related conditions in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:S5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1972;1653–8 doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham K. Identifying and measuring alcohol abuse among the elderly: serious problems with existing instrumentation. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47:322–6. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blow FC, Brower KJ, Schulenberg JE, et al. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test—Geriatric Version (MAST-G). A new elderly-specific screening instrument. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:372. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1:325–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihas AA, Tavassoli M. Laboratory markers of ethanol intake and abuse: a critical appraisal. Am J Med Sci. 1992;303:415–28. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199206000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]