Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the association between patient literacy and hospitalization.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study.

SETTING

Urban public hospital.

PATIENTS

A total of 979 emergency department patients who participated in the Literacy in Health Care study and had completed an intake interview and literacy testing with the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults were eligible for this study. Of these, 958 (97.8%) had an electronic medical record available for 1994 and 1995.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Hospital admissions to Grady Memorial Hospital during 1994 and 1995 were determined by the hospital information system. We used multivariate logistic regression to determine the independent association between inadequate functional health literacy and hospital admission. Patients with inadequate literacy were twice as likely as patients with adequate literacy to be hospitalized during 1994 and 1995 (31.5% vs 14.9%, p < .001). After adjusting for age, gender, race, self-reported health, socioeconomic status, and health insurance, patients with inadequate literacy were more likely to be hospitalized than patients with adequate literacy (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13, 2.53). The association between inadequate literacy and hospital admission was strongest among patients who had been hospitalized in the year before study entry (OR 3.15; 95% CI 1.45, 6.85).

CONCLUSIONS

In this study population, patients with inadequate functional health literacy had an increased risk of hospital admission.

Keywords: educational status, socioeconomic factors, patient admission, patient readmission, hospitalization

Because of the explosive growth in the number of successful medical treatments, patients with chronic medical problems currently face tremendous learning demands. For example, a patient who was lucky enough to survive an acute myocardial infarction in the 1960s was typically discharged with only a pat on the back and wishes for good luck. In the 1990s, such a patient is likely to be discharged on a regimen of aspirin, a β-blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and possibly a low-salt and low-cholesterol diet and medications to control hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. A patient's ability to learn this regimen and follow it correctly will determine a trajectory toward recovery or a downward path to recurrent myocardial infarction, disability, and death.

Millions of Americans are ill-equipped to meet this type of educational challenge. In 1993, the National Adult Literacy Survey reported that more than 40 million adult Americans were functionally illiterate, meaning they could not perform the basic reading tasks necessary to function fully in society.1 Another 50 million had marginal reading skills.1 Similarly, a study conducted at two public hospitals found that one third of English-speaking patients were unable to read and comprehend the most basic health-related materials.2 Inadequate literacy is especially prevalent among the elderly, the population with the largest burden of chronic disease and, consequently, the greatest health-related reading demands.1, 2 In the National Adult Literacy Survey, 44% of adults aged 65 years and older were classified as functionally illiterate.1 In addition to their low educational attainment, the functionally illiterate are uniquely vulnerable because they are more likely to be poor, unemployed, and working in jobs subject to seasonal and general economic fluctuations 1 ; they clearly occupy the lowest rung of the socioeconomic ladder.

Previous studies have shown that persons with limited reading ability are likely to struggle with the routine reading tasks they encounter in the health care setting, such as reading prescription bottles, appointment slips, self-care instructions, and health education brochures.2–16 Similarly, persons with inadequate literacy who suffer from chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) are less likely to know the basic elements of how to care for their medical problems, even if they have gone to special classes to learn how to manage their condition.17 Finally, inadequate literacy and low educational level are associated with worse health outcomes.18–25 Kitagawa and Hauser found a linear relation between the number of years of school completed and mortality ratios.18 Among a group of 11,000 hypertensive patients in a hypertension detection and follow-up program, 5-year all-cause mortality was inversely related to educational level.25 Despite the important implications of the high prevalence of inadequate literacy for patient care and health care delivery, the problem remains hidden. Most adults with limited reading ability are deeply ashamed of it and unwilling to reveal it to others,26 and most health care providers do not systematically ask patients about reading difficulties or screen patients' reading ability despite the availability of rapid screening instruments.27

The high prevalence of inadequate literacy may also have important cost implications. Kuh and Stirling found the risk of hospitalization for diseases of the female genital system was more than twice as high for the least educated compared with the most educated women.28 Weiss and coworkers found no relation between literacy and medical care costs for a random sample of Medicaid recipients in Arizona.29 However, the patient population included too few patients in poor health at baseline to have adequate power to detect clinically important differences in health care use. We have reported previously that patients with inadequate literacy were more likely to say they had been hospitalized in the previous year, even after adjustment for age, self-reported health, and socioeconomic markers.30 A more accurate understanding of the relation between literacy and health care costs is crucial. If inadequate literacy leads to worse health outcomes and higher health care costs, this may motivate payers to develop education programs to reach all patients, regardless of reading ability.

To explore the relation between health literacy (the ability to read and understand health-related materials) and hospital admissions (a major determinant of health care costs), we followed a cohort of patients for 2 years whose reading had been tested using the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA)31 to determine whether patients with inadequate literacy have an increased risk of hospital admission. In addition, we examined whether inadequate literacy is more strongly associated with hospital admission than the number of years of school completed. It is much easier to determine the number of years of school completed than to actually measure literacy. However, the number of years of school completed is an inaccurate measure of true educational attainment (i.e., someone may have completed high school but have poor reading skills, limited vocabulary, little knowledge of health issues, and a weak ability to acquire and use new knowledge). Because literacy is a more direct measure of educational attainment, we hypothesized it would be a better predictor of the risk of hospital admission.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

This study was conducted at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. The original study design and contact forms were approved by the Human Investigations Committee. Patients entered the study from November 1993 through March 1994. Patients presenting to the Emergency Care Center and Walk-In Clinic with nonurgent medical problems between 9 amand 5 pmwere eligible. Exclusion criteria included age less than 18 years, unintelligible speech, overt psychiatric illness, police custody, English as a second language, and being too ill to participate. Eligible patients were enrolled sequentially from the medical charts of those waiting to be seen.

Independent Variables

A face-to-face interview was conducted to collect information about demographics and other patient characteristics. We used car ownership, telephone ownership, and receipt of financial assistance to buy food (e.g., food stamps) as indicators of patients' economic status because many patients are unwilling to give information about their income. Visual acuity was screened using a pocket vision screener (Rosenbaum, Graham-Field Surgical Company; New Hyde Park, N.Y.), and patients with vision worse than 20/100 were excluded.

Patients were then administered the TOFHLA to measure their functional health literacy.31 The TOFHLA, a previously validated instrument that uses actual materials patients might encounter in the health care setting, consists of two parts. The reading comprehension section is a 50-item test using the modified Cloze procedure.32 It measures patients' ability to read and understand three prose passages: preparation for an upper gastrointestinal series, the patient rights and responsibilities section of a Medicaid application, and a standard hospital informed consent. The numeracy section is a 17-item test with numerical information that tests comprehension of directions for taking medicines, monitoring blood glucose level, keeping clinic appointments, and obtaining financial assistance using actual hospital forms and prescription bottles. The numeracy score is multiplied by a constant, 2.941, to create a score from 0 to 50, the same range as for the reading comprehension section. The sum of the two sections yields the TOFHLA score, which ranges from 0 to 100. Scores on the TOFHLA are classified and interpreted as follows: 0 to 59, inadequate literacy; 60 to 74, marginal literacy; and 75 to 100, adequate literacy. Further details regarding reading ability of patients in these categories and a full description of study recruitment have been published previously.2

Dependent Variable

We used the information system for Grady Memorial Hospital to determine hospitalizations. Most patients at Grady are poor and can receive medical care for free or at reduced cost with the hospital's ability-to-pay plan; therefore, the patient population is relatively stable, and the Grady information system should capture the vast majority of hospitalizations for the study population. Patients' hospital identification number was obtained at the time of study enrollment, and we used this to search the hospital information system for all admissions during 1994 and 1995 for patients enrolled in the study. A total of 979 patients completed the intake interview and literacy testing with the TOFHLA and were eligible for this study. Of these, 958 (97.8%) had an electronic medical record available. For each patient, we determined the number of hospitalizations and the principal discharge diagnosis ICD-9 code for each admission.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS and BMDP. Categorical variables were compared using unadjusted χ2statistics, and continuous variables were compared with two-sided Student's t tests or analysis of variance. We created two variables indicating “one or more hospitalization” and “two or more hospitalizations” (yes = 1, no = 0). The significance of the relation between these variables and literacy was first tested using unadjusted χ2tests. We then used logistic regression to determine whether literacy was independently associated with having one or more hospital admission. The independent variables in the model specified a priori were age, gender, race, self-reported usual health during the month prior to study entry (ranging from excellent to poor), economic indicators, and type of health insurance coverage. The number of years of school completed was highly correlated with literacy (Spearman's ρ = 0.57). We therefore analyzed three models: health literacy alone; the number of years of school completed (less than high school, high school, or more than high school), but not health literacy; and both health literacy and the number of years of school completed. Self-reported regular source of care and interaction terms for literacy and other variables were also examined but were not significant.

Finally, we determined the association between inadequate literacy and hospital admissions in a high-risk subgroup: patients who stated in their baseline interview that they had been hospitalized in the year before study entry. Because of the smaller number of patients (n= 187), we only included independent variables that had a p value ≤.10 in the logistic model. For all analyses, a p value of .05 was used to determine final statistical significance.

RESULTS

The median age of patients in the study was 40 years, 59% were female, and 92% were African American. Overall health was reported to be good to excellent for 53%, fair for 32%, and poor for 16%. Economic indicators showed that 39% did not own a telephone, 76% did not own a car, and 42% were receiving some form of assistance to buy food. Over half (56%) lacked any form of health insurance. A total of 503 patients had adequate literacy (53%), 122 (13%) had marginal functional health literacy, and 333 (35%) had inadequate literacy.

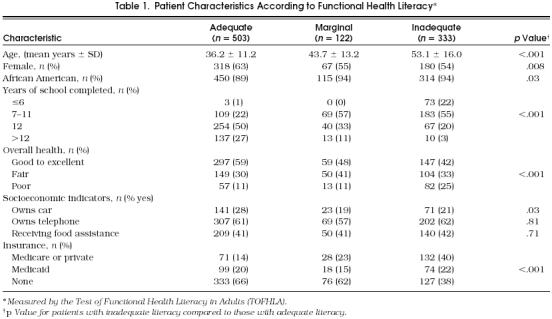

Literacy was significantly associated with several patient characteristics that could confound the relation between literacy and hospitalization (Table 1). Compared to patients with adequate literacy, those with inadequate literacy were older and more likely to be male, have Medicare or private insurance, report poor health, and not own a car. Of the patients with inadequate literacy, 23% had completed high school. Conversely, of the patients with adequate literacy, 23% had not completed high school. There were no differences in the proportion of patients who owned a car or who were receiving financial assistance to buy food.

Table 1.

Table Patient Characteristics According to Functional Health Literacy*

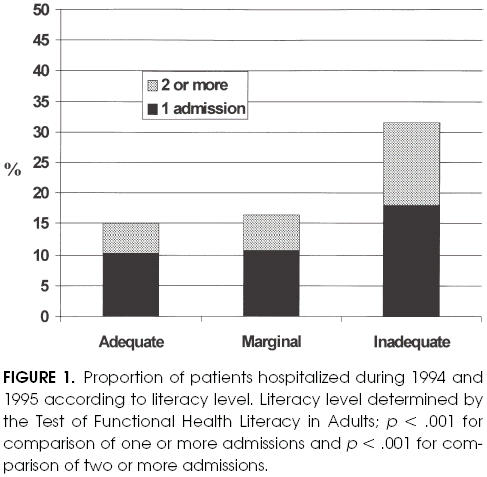

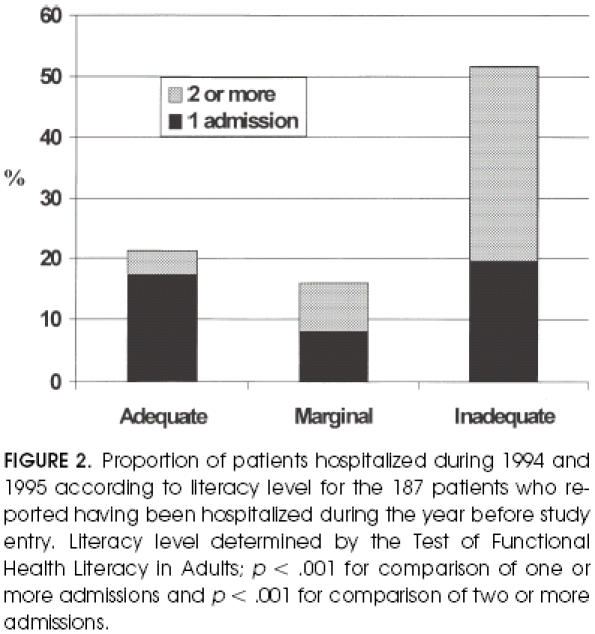

A total of 200 (21%) of the patients were hospitalized at least once during the 2-year study period, and 75 (8%) were hospitalized two or more times. Patients with inadequate literacy were more likely to have been hospitalized one or more times during 1994 and 1995 than patients with either marginal or adequate literacy (31.5%, 16.4%, and 14.9%, respectively;p < .001;Fig. 1); the difference between patients with marginal and those with adequate literacy was not significant. Patients with inadequate literacy were also more likely to have been hospitalized two or more times compared with patients with either marginal or adequate literacy (13.5%, 5.7%, and 4.6%, respectively;p < .001;Fig. 1). Simple stratified analyses showed that patients with inadequate literacy were more likely to have been hospitalized than patients with adequate literacy regardless of age, self-reported health, or insurance status (Table 2), although the differences were not statistically significant for most age groups because of the small number of patients in some of the cells. There were no significant differences in the ICD-9 discharge diagnoses between patients with inadequate and those with adequate literacy, although there were too few patients in any given category to definitively assess this finding.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients hospitalized during 1994 and 1995 according to literacy level. Literacy level determined by the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults;p < .001 for comparison of one or more admissions and p < .001 for comparison of two or more admissions.

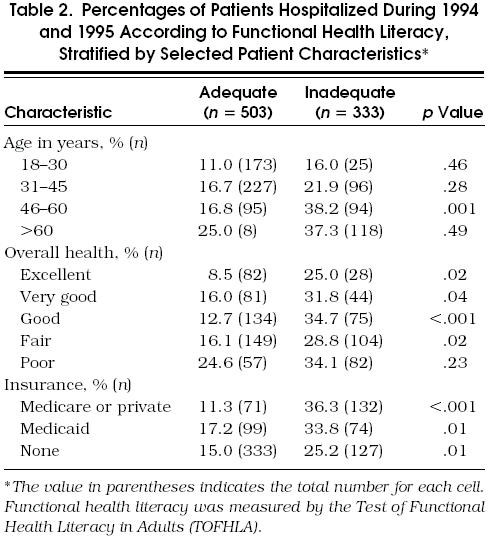

Table 2.

Table Percentages of Patients Hospitalized During 1994 and 1995 According to Functional Health Literacy, Stratified by Selected Patient Characteristics*

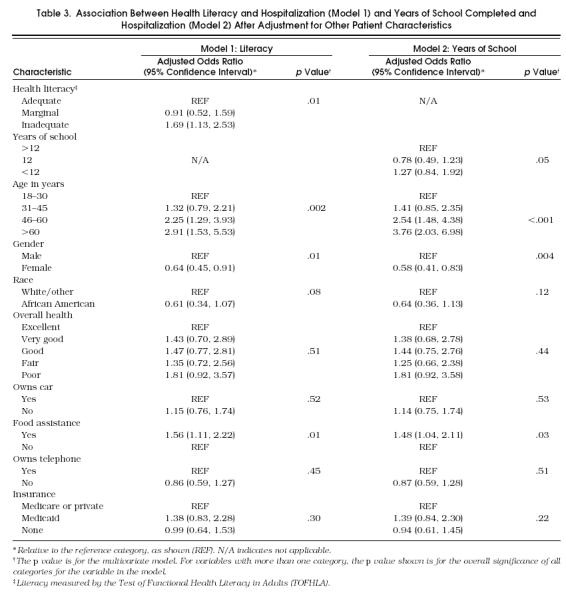

Several patient characteristics besides health literacy were associated with having one or more hospital admission in univariate analysis. Patients who were older, male, white, in worse health, receiving financial assistance to buy food, and had health insurance coverage (compared with patients without insurance) were more likely to be hospitalized (data not shown). After adjusting for other patient characteristics with logistic regression, the odds ratio (OR) for hospitalization for patients with inadequate literacy was 1.69 (95% confidence internal [CI] 1.13, 2.53) compared to patients with adequate literacy (Table 3, model 1). Age was the strongest predictor of hospital admission (overall p= .002; OR 2.91 for patients over 60 years old compared with ages 18 to 30), followed by inadequate literacy. When the number of years of school completed was used as the indicator of educational status instead of health literacy in the multivariate analysis (Table 3, model 2), the association with hospital admission was less than for health literacy (adjusted OR for those who did not complete high school compared with those with education beyond high school 1.27; 95% CI 0.84, 1.92).

Table 3.

Table Association Between Health Literacy and Hospitalization (Model 1) and Years of School Completed and Hospitalization (Model 2) After Adjustment for Other Patient Characteristics

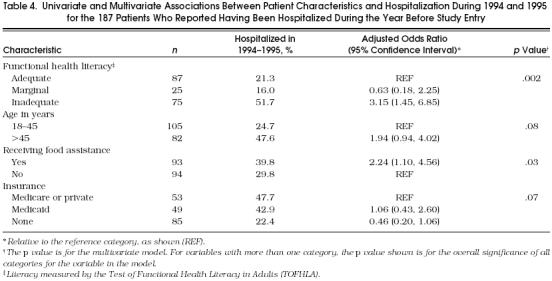

We also examined a subset of patients at particularly high risk of hospital admission: those who said they had been hospitalized in the year preceding study enrollment. At their baseline interview, 187 patients (19.5%) said they had been hospitalized one or more times in the year before study enrollment (75 with adequate, 25 with marginal, and 87 with inadequate literacy). A total of 21.3% of the patients with adequate literacy were hospitalized during 1994 and 1995, compared to 16.0% of patients with marginal literacy and 51.7% of patients with inadequate literacy (p < .001, Fig. 2). The adjusted OR for hospital admission for patients with inadequate literacy was 3.15 (95% CI 1.45, 6.85) compared to patients with adequate literacy after adjustment for age, economic indicators, and health insurance (Table 4

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients hospitalized during 1994 and 1995 according to literacy level for the 187 patients who reported having been hospitalized during the year before study entry. Literacy level determined by the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults;p < .001 for comparison of one or more admissions and p < .001 for comparison of two or more admissions.

Table 4.

Table Univariate and Multivariate Associations Between Patient Characteristics and Hospitalization During 1994 and 1995 for the 187 Patients Who Reported Having Been Hospitalized During the Year Before Study Entry

DISCUSSION

This exploratory study suggests that patients' reading ability is independently associated with their risk of hospitalization. Patients with inadequate literacy had more than twice the risk of being hospitalized during 1994 and 1995. After adjusting for demographics, self-reported health, economic indicators, and health insurance coverage, patients with inadequate literacy were still more likely to be hospitalized (adjusted OR 1.69; 95% CI 1.13, 2.53). Inadequate literacy had an even stronger association among patients who said they had been hospitalized in the year before study entry (adjusted OR 3.15; 95% CI 1.45, 6.85). This latter group may have more complex treatment plans, or they may have more precarious health so that even minor misunderstandings about medication instructions or care plans may result in deteriorating health and hospital admission.

When thinking about possible explanations for the relation between literacy and hospital admission, it is important to recognize that inadequate literacy is not only a reading problem. Patients with inadequate literacy are likely to struggle with oral as well as written communication. For example, patients with poor reading ability may have more difficulty understanding oral instructions because of limited vocabulary or difficulty following complex sentence structure. They may also have limited problem-solving abilities or be less likely to change behavior on the basis of new information. Thus, inadequate health literacy may be a marker for a complicated array of problems with provider-patient communication and health behaviors that affect the risk of hospital admission but are not directly related to reading ability.

Previous research suggests that inadequate literacy could directly affect patients' health and the risk of hospital admission. Patients with inadequate functional health literacy are more likely to be unable to read or to misread directions on prescription labels.2 This can lead to patients taking either too much or too little of their prescribed medications.3 Patients with inadequate functional health literacy are also less likely to know basic elements of their care plan for diabetes and hypertension (e.g., low-salt diet, symptoms of hypoglycemia, normal range for blood pressure or blood glucose level).17 If patients lack knowledge of their medications and self-management techniques, they may be more vulnerable to persistent health problems or even have worsening health that eventually results in hospital admission.

The association between health literacy and hospital admission could also be explained by inadequate adjustment for health status differences between patients with adequate and those with inadequate literacy. Although we adjusted for differences in patients' self-reported health, it is possible that other indicators of health status (e.g., chronic conditions, health-related quality of life) would increase the effect of health status in the model and decrease the effect of inadequate literacy. However, self-reported overall health is significantly associated with other measures of self-reported health and the presence of chronic disease.33, 34 Therefore, the addition of other health measures to the model would be unlikely to have a large enough independent effect to explain entirely the increased risk of hospital admission among patients with inadequate literacy. In addition, some of the increased risk of hospital admission for patients with inadequate literacy could result from a higher prevalence of adverse health behaviors (i.e., smoking, alcohol or drug use, or diet). Previous studies have shown a strong link between the number of years of school completed and health behaviors.35 We did not collect information on health behaviors, so we could not adjust for these factors.

Health literacy was associated more strongly with hospital admission than with the number of years of school completed. This should not be surprising. The number of years of school completed represents education attempted, whereas health literacy is a more valid indicator of educational attainment(i.e., what was actually learned during the years of schooling). For example, 67 (18.6%) of 361 high school graduates in this study had inadequate literacy, and 40 (11.1%) had marginal literacy according to the TOFHLA (see Table 1). In addition to being a more accurate measure of educational attainment, health literacy may be an indicator of someone's ability to acquire new information and complete complex, cognitive tasks. Learning ability, rather than reading ability per se, may be the true mediator of the relation between health literacy and hospital admission, and this may not be captured by the years of school completed.

There are several important limitations to this study. First, we only used data on hospital admissions at Grady Memorial Hospital. If patients with adequate reading skills were more likely to obtain health insurance or shift their care to sites outside the Grady Health System, then analyzing hospital admissions at Grady Memorial Hospital alone would make it appear that patients with adequate literacy were less likely to be hospitalized. If this were the case, then we would expect the relation between literacy and hospitalization to be stronger for 1995 than for 1994, because more patients with adequate literacy would have migrated out of the Grady Health System by 1995. However, there was no difference in the relation between literacy and hospital admission for the two study years and no difference according to patients' reported regular source of care (data not shown). This suggests that out-migration by patients with better reading ability does not explain our findings.

Second, we enrolled patients who were seeking medical care in the walk-in clinic or the emergency department. More than half the patients said they were not followed by a regular physician or that they used the emergency department as their regular source of care. Persons with inadequate reading skills may have more difficulty than those with better reading ability when trying to manage their medical problems and coordinate their medical care without the assistance of a regular provider. In addition, patients in primary care settings may have more resources available to ameliorate the problems created by inadequate literacy (i.e., a physician knowledgeable of the patient's reading problems, nursing staff, or health educators). The effect of inadequate literacy in other settings may therefore be less. The relation between literacy, health care use, and health outcomes will probably vary depending on the patient population, practice setting, and characteristics of the health care system.

Patients with inadequate literacy form a uniquely vulnerable group. They have worse health, fewer economic resources, and less ability to successfully navigate the health care system and complete personal health care tasks. This issue is of particular concern for the elderly. In 1993, 36 million Americans were enrolled in Medicare.36 According to the 1993 National Adult Literacy Survey, 44% of Americans over the age of 65 were functionally illiterate, indicating there were approximately 16 million functionally illiterate Medicare beneficiaries.1 If these individuals have higher than expected hospital costs, and if these excess hospitalizations could have been prevented by improved communication and education, then Medicare hospital costs could be reduced substantially. Further studies are necessary to determine whether the results of this study are generalizable to other patient populations, whether the relation results directly from problems with patient-provider communication, and whether innovative approaches to improve communication and patient education can improve outcomes.37–49

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Randall Cebul, MD, and Susan Payne, PhD, for their helpful comments regarding the manuscript and Stephen Somers for his continued support of this work.

References

- 1.Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC:: National Center for Education, US Dept of Education;; 1993. Adult Literacy in America: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams MV, Parker R, Baker D. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274:1677–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:329–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.6.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers RD. Emergency department patient literacy and the readability of patient-directed materials. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:124–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doak L, Doak C. Patient comprehension profiles: recent findings and strategies. Patient Couns Health Educ. 1980;2:101–6. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(80)80049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundner T. On the readability of surgical consent forms. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:900–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004173021606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leichter S, Nieman J, Moore R, Collins P, Rhodes A. Readability of self-care instructional pamphlets for diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1981;4:627–30. doi: 10.2337/diacare.4.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holcomb C. Reading difficulty of informational materials from a health maintenance organization. J Reading. 1981;25:130–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd M, Citro K. Cardiac patient education literature: can patients read what we give them? J Card Rehab. 1983;3:513–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeal B, Salisbury Z, Baumgardner P, Wheeler F. Comprehension assessment of diabetes education program participants. Diabetes Care. 1984;7:232–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.7.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaycox S. Smoking literature and literacy levels. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1058. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1058. . Letter. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis T, Crouch M, Willis G, Miller S, Abdehou D. The gap between patient reading comprehension and the readability of patient education materials. J Fam Pract. 1990;31:533–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson R, Davis T, Bairnsfather L, George R, Crouch M, Gault H. Patient reading ability: an overlooked problem in health care. South Med J. 1991;84:1172–5. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis T, Mayeaux E, Fredrickson D, Bocchini J, Jackson R, Murphy P. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93:460–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolly B, Scott J, Feied C, Sanford S. Functional illiteracy among emergency department patients: a preliminary study. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:573–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spandorfer J, Karras D, Hughes L, Caputo C. Comprehension of discharge instructions by patients in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:71–4. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM. Differences in disease knowledge between patients with adequate and inadequate functional health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.2.166. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitagawa EM, Hauser PM. Study in Socioeconomic Epidemiology. Cambridge, Mass:: Harvard University Press;; 1973. Differential Mortality in the United States: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guralnik JM, Land KC, Blazer D, Fillenbaum GG, Branch LG. Educational status and active life expectancy among older blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:110–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman JJ, Makuc DM, Kleinman JC, Cornoni-Huntley J. National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:919–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurowitz JC. Toward a social policy for health. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:130–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson MD. Socioeconomic status and childhood mortality in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1131–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.8.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, Davies G, Davis VG, Braunwald E. Comparison of long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction in patients never graduated from high school with that in more educated patients. Multicenter Investigation Limitation Infarct Size (MILIS) Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:1031–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90568-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keil JE, Sutherland SE, Knapp RG, Lackland DT, Gazes PC, Tyroler HA. Mortality rates and risk factors for coronary disease in black as compared with white men and women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:73–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamler R, Hardy RJ, Payne GH. Educational level and five-year all-cause mortality in the hypertension detection and follow-up program. Hypertension. 1987;9:641–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: the unspoken connection. Patient Educ Counseling. 1996;27:33–9. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuh D, Stirling S. Socioeconomic variation in admission for disease of female genital system and breast in a national cohort aged 15–43. BMJ. 1995;311:840–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss BD, Blanchard JS, McGee DL, et al. Illiteracy among Medicaid recipients and its relationship to health care costs. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1994;5:99–111. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss JR. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1027–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA): a new instrument for measuring patient's literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor W. Cloze procedure: a new tool for measuring readability. Journalism Q. 1953;30:415–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JE. Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Mass: The Health Institute: New England Medical Center;; 1993. SF-36 Health Survey: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prevalence of selected risk factors for chronic disease by education level in racial/ethnic populations—United States, 1991–1992. MMWR. 1995;1004:894–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baltimore, Md: Health Care Financing Administration; 1996. Health Care Financing Review: Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussey LC. Minimizing effects of low literacy on medication knowledge and compliance among the elderly. Clin Nurs Res. 1994;3:132–45. doi: 10.1177/105477389400300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revell L. Understanding, identifying, and teaching the low-literacy patient. Semin Periop Nurs. 1994;3:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berger D, Inkelas M, Myhre S, Mishler A. Developing health education materials for inner-city low literacy parents. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:168–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plimpton S, Root J. Materials and strategies that work in low literacy health communication. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:86–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meade CD, McKinney WP, Barnas GP. Educating patients with limited literacy skills: the effectiveness of printed and videotaped materials about colon cancer. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:119–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown P, Ames N, Mettger W, et al. Closing the comprehension gap: low literacy and the Cancer Information Service. Monogr Natl Cancer Inst. 1993:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overland JE, Hoskins PL, McGill MJ, Yue DK. Low literacy: a problem in diabetes education. Diabetic Med. 1993;10:847–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1993.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss BD. Identifying and communicating with patients who have poor literacy skills. Fam Med. 1993;25:369–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hussey LC. Overcoming the clinical barriers of low literacy and medication noncompliance among the elderly. J Gerontol Nurs. 1991;17:27–9. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19910301-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. 2nd. Philadelphia, Pa:: J.B. Lippincott;; 1996. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Said MB, Consoli S, Jean J. A comparative study between a computer-aided education (ISIS) and habitual education techniques for hypertensive patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;(symp suppl):10–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michielutte R, Bahnson J, Dignan M, Schroeder E. The use of illustrations and narrative text style to improve readability of a health education borchure. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:251–60. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCabe B, Tysinger JW, Kreger M, Currwin A. A strategy for designing effective patient education materials. J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89:1290–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]