Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the relation of patient beliefs about medication usage and adherence to zidovudine (ZDV) therapy in persons with AIDS.

DESIGN

Face-to-face interviews were used to determine attitudes of persons with AIDS toward ZDV and other prescribed medications, history of ZDV usage, and sociodemographics.

SETTING

A public hospital infectious disease clinic, an AIDS day care program, and an inpatient unit in a voluntary hospital where care was provided cooperatively by staff and an informal–care partner.

PATIENTS/PARTICIPANTS

One hundred forty-one people with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome agreed to be reinterviewed as part of a longitudinal, New York City–based study examining outcomes related to quality of life. Initial recruitment procedures were to approach all active AIDS patients at each of the three sites between January and July of 1992; reinterviews, which were conducted an average of 6 months later, occurred from mid-1992 through May of 1993.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

The Zidovudine Drug Attitude Inventory was used to assess subjective feelings and attitudes concerning ZDV and prescribed medications in general. Respondents were grouped into five categories on the basis of their ZDV usage history: (1) “short-term” users (i.e., those who had been taking ZDV for 25 months or less); (2) “long-term” users (i.e., those who had been taking ZDV for more than 25 months); (3) self-terminated users; (4) doctor-terminated users; and (5) never users. Long-term users were likely to view ZDV as an illness prophylactic. In contrast, self-terminated users and never users were most likely to believe that ZDV caused adverse side effects and that medicine need not be taken as prescribed.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients’ beliefs about ZDV were significantly associated with adherence-related behavior. In particular, those who had self-terminated ZDV treatment believed that taking the drug was harmful, were skeptical of its ability to prevent illness, and felt that physicians’ directives about medication usage in general could be disregarded. These findings highlight the importance of educating patients about ZDV and of establishing regular patient-clinician exchanges concerning patients’ experiences with and beliefs concerning ZDV.

Keywords: adherence, zidovudine, patient beliefs

Zidovudine (ZDV) has been recognized as a leading antiretroviral therapy for the HIV since the release of clinical trials data in the late 1980s and early 1990s indicating that it delayed the development of symptomatic HIV infection and the onset of AIDS.1,2 Current clinical guidelines specify ZDV for a broad spectrum of symptomatic and asymptomatic HIV-infected patients3,4; it is estimated that over 600,000 persons in the United States alone are eligible for such treatment.5 Demand for ZDV is likely to increase still further in light of new findings indicating that its effectiveness is enhanced when it is used in combination with other antiretroviral agents.6

Despite the large and rapidly expanding pool of potential recipients of ZDV, the issue of ZDV adherence has received relatively little attention in the literature. What research has been conducted suggests that ZDV nonadherence is widespread, with estimated rates ranging from 12% to 42%.7–15 To date, numerous forms of nonadherence have been documented, including modification of the prescribed dosage levels, polypharmacy, and self-termination.16–18

Certain characteristics of ZDV and the ZDV regimen may actually promote nonadherence. The drug causes numerous side effects, which range from the merely discomforting (e.g., headache, nausea, bloating, vomiting, and dyspepsia),1,2,12 to the outright toxic (e.g., neutropenia, hematopoietic toxicity, and anemia); it is costly; the dosage regimen is onerous,13–15; and regular and sustained medical monitoring is necessary.15 Similar drawbacks have been identified for other types of antiretroviral regimens as well.4

Although a growing body of literature suggests that patients’ beliefs, perceptions, and explanations concerning illness and treatment are key factors in drug adherence,7, 19–24 there has been relatively little research on this issue in the context of ZDV. In this study, we seek to examine the association between patient attitudes about ZDV and medication in general and the self-termination of ZDV therapy. ZDV is a prophylactic treatment involving a complex and lengthy regimen. Such characteristics, which apply equally to the new anti-HIV combination drugs, have been shown to promote the development of noncompliant or “self-regulatory” behaviors.24 Identifying the attitudinal factors that encourage or thwart ZDV usage may prove helpful in identifying strategies to promote patient adherence to ZDV as well as to the new combination drug therapies.

BELIEFS AND ATTITUDES

Drug Adherence

The importance of patient beliefs for adherence is emphasized in the Health Belief Model (HBM), a biopsychosocial paradigm originally developed to explain health prevention behaviors.25 According to this model, adherence is linked to patient perceptions concerning: (1) personal susceptibility to illness or its consequences; (2) severity of illness; (3) the effectiveness or benefits associated with following the prescribed regimen; and (4) whether the costs involved in adhering to medical advice (e.g., cost, complexity, duration, side effects, and need to change behavior patterns) outweigh the perceived benefits. To date, empirical support for the HBM has been largely positive, although some inconsistent findings have been reported.26,27

One criticism of the HBM is its assumption that health-related beliefs are the single most salient influence on an individual’s decision to comply with prescribed regimens.24 An accumulating body of evidence suggests that adherence-related behaviors proceed from a broader array of personal assumptions and beliefs about illness and treatment,7, 19–24 beliefs that are shaped by a range of sociodemographic, familial, cultural, and experiential factors. Patients use these belief systems or “explanatory models” in an effort to assert control over their daily lives,24 their medical condition,19 or the patient-physician interaction,21 or to obtain more satisfactory treatment.20 Adherence is linked to beliefs that medicine is instrumental in preventing illness and in ensuring normal life functioning.24 Individual efforts to vary or terminate medication regimens (to “self-regulate”) reflect beliefs that the drug is inefficacious or that drug-associated side effects interfere with everyday life. Self-regulation may also represent an effort to evaluate disease progression (“testing”), to control medication dependency, to avoid being identified as a patient (“destigmatization”), or to prepare for specific social demands or situations (“practical practice”).

Zidovudine Adherence

HIV-infected individuals hold a diverse array of attitudes about ZDV.28 Such views are shaped by a variety of factors, including their own or others’ experience with the medication,19 negative publicity surrounding the marketing and pricing of ZDV,14 general mistrust of the government,16 results of medical research, and information obtained from other sources within the AIDS community, such as alternative therapies networks.17

To date, however, only a few studies have examined the relation between patient attitudes about ZDV and its usage. Among individuals offered ZDV, those accepting it have been shown to view: the drug as being highly beneficial to their health,28 be highly susceptible to other people’s opinions,28 and possess great confidence in the ability of “powerful others” to affect health outcomes.29 In contrast, those declining ZDV have been shown to be: highly internally motivated;28 concerned with possible disruption of their current lifestyle (e.g., intravenous drug use);29 fearful of potential ZDV-related side effects or toxicity;7,30 resentful of ZDV distribution and pricing policies;29 and likely to deny having any need for treatment.7 In one study, nonadherence with ZDV was explained in terms of such beliefs as the drug’s inefficacy, its ability to remind patients that they had AIDS, and its association with negative side effects.31 The strongest predictor of adherence was the belief that ZDV prolonged life.31 The decision to complement or supplant ZDV therapy with other drug regimens has been shown to reflect patient expectations concerning the positive treatment outcomes that will accrue from using such alternatives (e.g., delays in symptom onset, improvements in immunity, and reductions in symptoms).30

STUDY HYPOTHESES

To test hypotheses concerning the relation between attitudes about ZDV and self-termination of ZDV therapy, we identified five distinct ZDV user groups within our patient sample: (1) short-term users were current users who had been taking ZDV for 25 months or less (n = 31); (2) long-term users were current users who had been taking ZDV for more than the 25-month median (n = 31); (3) self-terminated users were those who had stopped using ZDV for reasons other than medical advice (n = 27); (4) physician-terminated users were those who had stopped using ZDV on physician orders (n = 41); and (5) never users were those who had never tried ZDV at all (n = 11).

From previous research, we expected that (1) self-terminated users would be more concerned with ZDV’s negative side effects than other patients18; (2) that current and medically terminated ZDV users would believe more strongly in medical authority than self-terminated users or those who had never used the drug24,28,29; (3) that never users would be more likely to view the benefits of ZDV as being insubstantial than those currently using the drug28; and (4) that long-term ZDV users would believe more strongly that ZDV was beneficial to their health than other patients.9

METHODS

Study Sample

Eligibility criteria for study participation were age of 18 years or older, sufficient physical stamina to withstand a 90-minute interview, no significant cognitive impairment, and Center for Disease Control and Prevention—defined AIDS (i.e., a CD4 count of less than 200 or occurrence of one or more opportunistic infections). Respondents’ self-reported AIDS status was confirmed by providers at each site who were familiar with the individual’s medical status.

Patient data were derived from reinterviews with a cohort of 141 persons with AIDS participating in a multisite, longitudinal study examining the impact of AIDS on functional status. Initial patient recruitment occurred from January through July of 1992 at three different sites in New York City: (1) an innovative inpatient service at a university hospital where only AIDS patients with an informal “care partner” could be admitted; (2) an infectious disease outpatient clinic at a large, municipal hospital; and, (3) an AIDS day care program that provided case management, counseling, health monitoring, and recreational services to persons with AIDS.

Procedures for recruiting persons with AIDS into the study differed by site. At the inpatient setting, the head admissions nurse and head social worker described the study to eligible patients at point of admission. The names of patients who indicated interest in participation were then given to a member of the research team for follow-up. At the other two sites, which served individuals with AIDS exclusively, research team interviewers approached individuals directly. Efforts were made to obtain as representative a patient group as possible at each site by recruiting at varying times each week.

At initial recruitment, 253 individuals were approached, of which 224 (88.5%) ultimately agreed to participate. The refusal rate was highest (25% or 14/55) at the inpatient setting, where individuals were sickest. In contrast, refusal rates at the outpatient clinic and the day care setting were much lower at 13.4% (16/119) and approximately 1% (1/81), respectively.

At the 6 months follow-up assessment 141 (63%) of the original respondent group agreed to be reinterviewed. These 141 individuals constitute the sample on which the following analysis is based. Of the 83 respondents who did not participate in the follow-up interview, the majority (n = 45) had died within the 6-month period. Another 18 were unable to be located, 11 were too sick to be interviewed, and 9 refused to participate. Attrition was highest (61%) among those individuals initially recruited while they were inpatients. Attrition rates among those recruited from the other two sites were lower at 40% (outpatient setting) and 21% (AIDS day care), respectively. More than 90% of respondents were reinterviewed at the treatment site where they had originally been recruited; the remainder were interviewed via telephone.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the two hospital-based sites and at New York University (the home institution of MYS and BDR at the time). The day care setting had no institutionalized review board procedure. Data at that site were collected under the aegis of the New York University–approved protocol. All participants received $15 per interview.

Data Collection

Data were collected by means of an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Subjects were asked if they had ever taken or were currently taking ZDV, and if so, for how long. Those stating that they had never taken or had stopped taking ZDV were asked to indicate their reasons for doing so on a multiple-choice response scale. Patients could endorse as many reasons as were applicable. Reasons for stopping were side effects; cost; belief that it was doing no good; belief that it was doing actual harm; drop in T-cell count; development of opportunistic infections; need for blood infusions; and doctor’s orders.

Data on drug attitudes were collected using an adapted version of the Drug Attitude Inventory, a 30-item self-report scale measuring both subjective feelings (e.g., “I feel happier”) and attitudes toward medication. (e.g., “I do not need medication once I am feeling better”). The Drug Attitude Inventory was originally designed to predict adherence among patients receiving neuroleptic treatment.32 In adapting it, we included items assessing subjective feelings and attitudes about medication in general and eliminated those that referred to specific side effects of neuroleptic treatment (e.g., “I feel like a zombie”). We supplemented the remaining 17 general medication items with 12 ZDV-specific items to create a new 29-item scale, the Zidovudine Drug Attitude Inventory (ZDAI).

The general medication items on the ZDAI represented seven domains: harmfulness (2 items), physician as controller of medication usage (3 items), patient as controller of medication usage (6 items), drug dependency (1 item), effectiveness in preventing illness (4 items), and reminder of patient status (1 item). The ZDV-specific items represented five domains: immune system booster (4 items); negative side effects (4 items); interference with daily functioning (2 items); reminder of patient status (1 item); and source of profiteering for drug companies (1 item). These domains were identified through a literature review of HIV-infected patients’ attitudes toward ZDV and via conversations between AIDS patients and their physician (A. Morrison, personal communication). All scale items were rated on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true).

Analytic Approach

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS-PC version 6.0. Examination of study data involved the following steps: First, identifying the central attitudinal dimensions measured by the ZDAI; next, examining the reliability of the resulting subscales; and, finally, determining which combination of factors distinguished among patients in each of the five ZDV user status groups.

To identify the central attitudinal dimensions assessed by the ZDAI, we factor analyzed the 29 ZDAI items using principal component analysis, a multivariate method used to summarize sources of variation among a set of items. Principal component analysis begins with a correlation matrix of these items. The goal is to identify the minimum number of components that account for the observed correlations. Components are essentially a weighted sum of the scale items. Once these components have been determined, an analysis is conducted to determine the spatial orientation that makes these components most interpretable in light of the original set of items. This procedure, termed “rotation to simple structure,” can be constrained to force all new components to be uncorrelated (i.e., to be “orthogonal”).33

To determine the reliability of components with three or more items, we analyzed their internal consistency using the Cronbach’s α statistic.34 Cronbach’s α is a correlation coefficient which ranges in value from 0.00 (completely unreliable) to 1.00 (completely reliable). The higher the α value, the more homogeneous the scale items and the more likely the scale is to elicit consistent responses.35

As a third analysis, we conducted multiple analyses of variance (MANOVA) and analyses of variance (ANOVA) procedures to examine how attitudes about medicine and ZDV related to ZDV user status. All but one of these cases (n = 140) were retained in the analysis; missing data appeared to be randomly scattered throughout groups and predictors. Mean substitution procedures were used to handle missing data points. Following the ANOVAs, we used a post hoc test, the Student-Newman-Keuls procedure, to determine which specific variables distinguished different user groups from one another.

RESULTS

Profile of Study Population

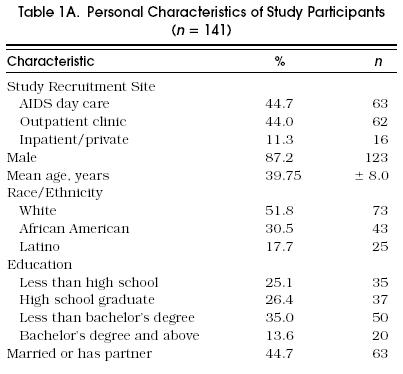

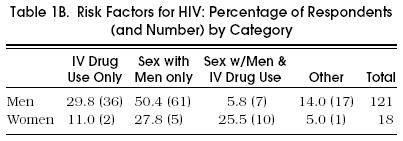

The majority of study respondents were recruited from one of the two outpatient care settings (88.7%) and were male (87.2%) Table 1a. Mean respondent age was 40. Although most were white (51.8%), close to one third of the sample was African American (30.5%), and another 17.7% was Hispanic. The level of educational attainment was high, with 75% of respondents reporting at least a high school education. Almost half (43.3%) reported being married or having a main partner. Risk factors by gender are shown in Table 1B.

Table 1A.

Personal Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1B.

Risk Factors for HIV: Percentage of Respondents (and Number) by Category

Most study participants (n = 62) were taking ZDV at the time they were interviewed. 31 (22.0%) had taken it more than 25 months and 31 (22.0%) had taken it for 25 months or less. Of the remaining respondents, 41 (29.1%) had discontinued use per medical recommendation; 27 (19.1%) had terminated treatment against doctor’s orders; and 11 (7.8%) had never taken the drug at all.

Among the five user groups, current ZDV users had been taking the drug for a longer period of time (mean 28.9 mo, SD 5.7) than those who had stopped ZDV treatment because of medical recommendation (mean 25.5 mo, SD 7.8) or than those who had self-terminated treatment (mean 7.7 mo, SD 9.2).

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Zidovudine User Status

To determine whether sociodemographic factors were related to ZDV user group status, we conducted intragroup comparisons on age, educational level, gender, income level, and race (white versus nonwhite) using ANOVA procedures. Results showed that doctor-terminated users were significantly more educated (high school graduate or above) than short-term ZDV users (with 11 years of education or less) (p < .05). Short-term users were more likely than long-term users to be female (p < .05). They were also more likely to be nonwhite than were long-term, self-terminated, or doctor-terminated users (p < .05). No significant differences were found among the five groups in terms of age and income level.

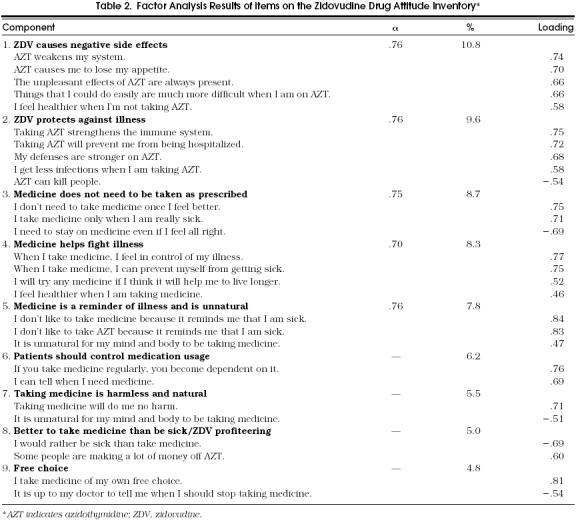

Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis results are presented in Table 2. To facilitate interpretation, item loadings of 0.45 or above on a given component are reported along with the total percentage of variance accounted for by each component.36 Two of the 29 items failed to load on any factor, (“For me, the good things about medicine outweigh the bad.” “I know better than my doctor when to take medicine”) and one item loaded onto two factors, (“It is unnatural for my mind and body to be taking medicines”).

Table 2.

Factor Analysis Results of items on the Zidovudine Drug Attitude Inventory*

Nine components were derived from the 29 scale items. These components reflect a range of attitudes concerning medicine and ZDV. Component 1 portrays ZDV as causing negative side effects (e.g., “AZT weakens the system,” “The unpleasant side effects of AZT are always present”). In contrast, component 2 stresses ZDV’s effectiveness in strengthening the immune system and in protecting against infections and hospitalization. Component 3 reflects the view that medicine need not be taken as prescribed, whereas component 4 views taking medicine as a way to control illness and promote wellness.

Components 5 and 6 view both medicine and ZDV negatively. According to component 5, medicine and ZDV are reminders of being sick and that taking medicine is unnatural. Component 6 stresses that medication usage must be controlled and that ZDV is ineffective. In contrast, component 7 portrays medicine as benign. Similarly, component 8 reflects the view that medicine in general is beneficial (e.g., “The good things about medicine outweigh the bad”) but also the view that ZDV has been a source of drug profiteering. Component 9 emphasizes that taking medicine is a matter of individual free choice.

Reliability

Table 2 also presents internal consistency coefficients for the five components that contained three or more items. The α coefficient values exceeded 0.70 for all five scales, a level indicating strong internal consistency.37 Disattenuated correlations among the subscales ranged from 0.01 to 0.62 with a median of 0.17.

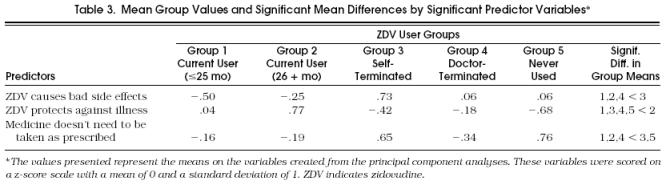

Drug Attitudes and Zidovudine User Group Membership

A MANOVA procedure was conducted to explore whether drug attitudes were related to ZDV user group membership. MANOVA results showed that there were significant differences among the groups in terms of drug attitudes (Wilks λ = 0.68, p < .0001).

The Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc procedure was conducted to identify the drug attitudes that reliably separated one group from another. Results, summarized in Table 3, show the mean values on the drug attitude variables for each ZDV user group. These variables, each of which represents a composite of ZDAI scale items, were scored on a z-score scale with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Thus, for example, a mean group score of 0.88 represents a value of almost one full standard deviation above the mean.

Table 3.

Mean Group Values and Significant Mean Differences by Significant Predictor Variables*

Three drug attitudes emerged from the post hoc test analysis as significantly distinguishing among individuals in the five user group categories:

ZDV causes negative side effects. Results showed that respondents who had self-terminated their ZDV therapy strongly believed that ZDV causes negative side effects while current ZDV users were least likely to view the drug in this way

ZDV protects against illness. Individuals who had been taking ZDV for 26 months or more believed that ZDV could ward off infection and prevent hospitalization

Medicine need not be taken as prescribed. Both never users and self-terminated users felt strongly that medications did not need to be taken as prescribed, while current ZDV users and those who had terminated ZDV use per doctor's orders were least likely to shar this attitude

DISCUSSION

Recent breakthroughs in understanding the pathogenesis and treatment of HIV infection confirm the importance of sustained antiretroviral treatment for the medical management of this viral illness.38–43 Antiretroviral treatment options for HIV infection continue to expand rapidly. In addition to ZDV, six nucleoside or nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors and three protease inhibitors are currently licensed for use.40 Increasingly, clinicians are prescribing one or more of these antiretroviral therapies at the earliest stages of HIV infection.4,40 One byproduct of this lengthened treatment span is an increased likelihood that patients will become nonadherent.

Understanding patients’ beliefs about ZDV has important clinical implications for combating nonadherence. Study results support our four original hypothesis. First, adherence is linked to personal beliefs about medicine’s effectiveness and to the individual’s role in combatting illness. We found that individuals who had self-terminated ZDV therapy were most concerned about the drug’s negative side effects. Second, current and doctor-terminated ZDV users were the most likely to agree that medicine should be taken as prescribed. Third, never users were significantly less likely than current ZDV users to believe that ZDV protects against illness. Fourth, we found that long-term users believed more strongly in ZDV’s efficacy than other study respondents, including short-term users.

Support for these findings can be found in previous research. In a study of asymptomatic HIV-positive patients, factors that were shown to distinguish decliners of ZDV therapy from acceptors included beliefs about the drug’s efficacy and the extent to which the individual responded to internal cues (e.g., symptoms) as opposed to external signs (e.g., physician recommendations).28 Similarly, decliners saw little if any benefit in using ZDV and relied heavily on internal bodily cues to decide whether or not to take ZDV.28 In a second study, Samet et al. found that perceived efficacy of ZDV therapy was a critical predictor of adherence.31 Individuals who believed that ZDV prolonged life were four times more likely to have high rates of ZDV adherence than those who did not. Factors contributing to nonadherence included beliefs that the drug did not help (13%) and that taking ZDV was a reminder of having AIDS (7%).

Siegel and colleagues found that HIV patients’ rejection of HIV-related treatment was associated with a general distrust of the medical establishment and with beliefs that their physician did not endorse a holistic approach in combatting illness, was not sufficiently acquainted with the particulars of their medical case, and was not well informed about HIV treatment.43 In contrast, acceptors of conventional medical treatment viewed drugs as a way to gain control over their illness. Interestingly, acceptors were more likely not only to take prescribed therapies but also to modify them or to use them in conjunction with nonprescribed “alternative” treatments.43

A limitation common to all these studies, including the current one, is that drug attitudes were not measured prospectively from the time of treatment initiation. Understanding the time frame in which such attitudes develop is useful for designing intervention strategies to reduce nonadherence.

Study results suggest that drug attitudes reflect an experiential component as well. Self-terminated users, who had taken ZDV for an average of almost 8 months, expressed the greatest concern about ZDV’s side effects, suggesting that they might have been particularly vulnerable to the drug’s negative physiologic sequelae. Ongoing assessments of patients’ drug attitudes subsequent to treatment initiation could identify such reactions as they arise during the course of therapy. These assessments might also help promote better patient-clinician communication, alleviate feelings of distrust about medical authority, and enhance patients’ sense of control over their treatment course.

In addition to the cross-sectional design, the current study has several other limitations of note. First, we assessed only the most extreme form of nonadherence—self-termination of treatment. Other types of nonadherence, such as experimentation with dosage levels or supplementation of ZDV with other, nonprescribed drug treatments, were not examined. Second, we relied exclusively on patient self-report for assessing adherence. Self-report is prone to biases and inaccuracies in recall and has been shown to underestimate actual nonadherence levels.44–46 Further validation of self-report data via physiologic assessments or nurse-based ratings would be valuable.45,46

A third limitation is that study participants were drawn from three different service settings within New York City. As a result, the extent to which findings apply to persons with AIDS in other settings or living in other geographic areas is unknown. Fourth and last, the number of respondents within each of the ZDV user categories was small, particularly in the self-terminated user (n =27) and never user (n = 11) groups. These limitations in sample size may have reduced our ability to detect significant group differences.

Further work is needed to test the generalizability of our findings concerning the association between drug attitudes and ZDV adherence. Such research should be conducted longitudinally so as to permit analysis of possible causal relations among these variables and in larger patient samples. Future empirical studies should also document the type of medical treatment patients receive and the nature of their interactions with providers in order to ascertain the contribution of health system factors to treatment adherence. Finally, the existing inventory of drug attitude and belief domains should be revised. Only three of the nine components differentiated among groups. Additional items or entirely new domains might enhance measurement sensitivity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fischl MA, Richman DD, Grieco MH, et al. The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:185–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707233170401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volberding PA, Lagakos SW, Koch MA, et al. Zidovudine in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:941–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004053221401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sande MA, Carpenter CC, Cobbs CG, Holmes KK, Sanford JP, for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases State-of-the-Art Panel on Anti-Retroviral Therapy for Adult HIV-Infected Patients Antiretroviral therapy for adult HIV-infected patients: recommendations from a state-of-the-art conference. JAMA. 1993;270:2583–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter CCJ, Fischl MA, Hammer SM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in 1996. JAMA. 1996;276(4):146–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. About 600,000 Americans to require therapy in 1993. AIDS Update. 1990:3.

- 6.Eron JJ, Benoit SL, Jemsek J, et al. Treatment with lamivudine, zidovudine, or both in HIV-positive patients with 200 to 500 CD4+ cells per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1662–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels JE, Hendrix J, Hilton M, Marantz PR, Sloan M, Small CB. Zidovudine therapy in an inner city population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:877–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selwyn PA, Feingold AR, Iezza A, et al. Primary care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in a methadone maintenance treatment program. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:761–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-9-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson W, O’Connor BB, McGregor RR, Schwartz JS. Patient use and assessment of conventional and alternative therapies for HIV infection and AIDS. AIDS. 1993;7:561–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craven DE, Leibman HA, Fuller J, et al. AIDS in intravenous drug users: issues related to enrollment in clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:645–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hand R. Alternative therapies used by patients with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:672–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richman DD, Andrews J. Results of continued monitoring of participants in the placebo-controlled trial of zidovudine for serious human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med. 1988;85:208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright EJ, Bodnar J. ZDV: hope for many, help for few. Health Soc Work. 1992;17:253–60. doi: 10.1093/hsw/17.4.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nussbaum B. Vol. 176. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1991. An old boy network. In: Good Intentions: How Big Business and the Medical Establishment Are Corrupting the Fight Against AIDS, Alzheimer’s, Cancer and More. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichman LB. Compliance with zidovudine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:333–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-332_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahms D. Alternative therapies in HIV Infection. AIDS. 1990;4:1179–87. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199012000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenblatt RM, Hollander H, McMaster JR, Henke CJ. Polypharmacy among patients attending an AIDS clinic: utilitzation of prescribed, unorthodox and investigational drugs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:136–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowan FM, Jones G, Bingham J, et al. Use of dizovudine for drug misusers infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1989;18:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(89)80081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:507–13. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes-Bautista DE. Modifying the treatment: patient compliance, patient control and medical care. Soc Sci Med. 1976;10:233–8. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(76)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stimson GV. Obeying doctor’s orders: a view from the other side. Soc Sci Med. 1974;8:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(74)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meichenbaum D, Turk DC. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1987. Factors affecting adherence. In: Facilitating Treatment Adherence: A Practitioner’s Guidebook; pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright AL, Morgan WJ. On the creation of “problem” patients. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:951–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90142-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conrad P. The meaning of medications: another look at compliance. Soc Sci Med. 1985;40:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker MH, Maiman LA, Kirscht JP, Haefner DP, Drachman RH, Taylor DW. Patient perceptions and adherence: recent studies of the Health Belief Model. In: Haynes RB, et al., editors. Adherence with Health Care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979. pp. 78–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stillman MJ. Women’s health beliefs about breast cancer and breast self-examination. Nurs Res. 1977;26:121–7. doi: 10.1097/00006199-197703000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor DW. A test of the Health Belief Model in hypertension. In: Haynes RB, et al., editors. Adherence with Health Care. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979. pp. 107–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catt S, Stygall J, Catalan J. 1992. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Health beliefs of HIV asymptomatic individuals about taking zidovudine (ZDV). VIII International Conference on AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Todak G, Kertzner R, Remien RH, et al. San Francisco, Calif.: 1991. Psychosocial factors in the decision to decline zidovudine (ZDV) treatment in HIV seropositive gay men. VII International Conference on AIDS. Abstract PoD 5582. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor BB, Lazar JS, Anderson WH. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1992. Ethnographic study of HIV alternative therapies. VIII International Conference on AIDS/III STD World Congress. Abstract PoB3398. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samet JH, Libman H, Steger KA, et al. Compliance with zidovudine therapy in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus, type 1: a cross-sectional study in a municipal hospital clinic. Am J Med. 1992;92:495–502. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood MR. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–83. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1989. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDowell I, Newell C, editors. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comrey AL. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1973. A First Course in Factor Analysis; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nunnally JC. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1978. Psychometric Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ushijima H, Kunisada T, Kitamura T, Muller WE. Synergistic effect of recombinant CD4-immunoglobulin in combination with azidothymidine, dideoxyinosine and 0.5 beta-monoclonal antibody on human immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro. Lett Appl Microbiol (Engl) 1994;19:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corey L, Holmes KK. Therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection—what have we learned? N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1142–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammer SM, Katzenstein DA, Hughes MD, et al. A trial comparing nucleoside monotherapy with combination therapy in HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts from 200 to 500 per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1081–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katztenstein DA, Hammer SM, Hughes MD, et al. The relation of virologic and immunologic markers to clinical outcomes after nucleoside therapy in HIV-infected adults with 200 to 500 CD4 cells per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1091–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saravolatz LD, Winslow DL, Collins G, et al. Zidovudine alone or in combination with didanosine or zalcitabine in HIV-infected patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or fewer than 200 CD4 cells per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1099–1106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegel K, Raveis VH, Krauss BJ. Factors associated with urban gay men’s treatment initiation decisions for HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev. 1992;4:135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnhold RG, Adebonojo FO, Callas ER, Callas J, Carte E, Stein RC. Patients and prescriptions: comprehension and compliance with medical instructions in a suburban pediatric practice. Clin Pediatr. 1970;9:645–51. doi: 10.1177/000992287000901107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilcox DRC, Gillan R, Hare EH. Do psychiatric out-patients take their drugs? BMJ. 1965;2:790–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5465.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morse EV, Simon PM, Coburn M, Hyslop N, Greenspan D, Balson PM. Determinants of subject compliance within an experimental anti-HIV drug protocol. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:1161–7. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90093-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]