Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine why residents present certain cases and not others at morning report (MR) in an institution that permits residents the free choice of cases.

DESIGN/PARTICIPANTS

Prospective survey of 10 second- and third-year residents assigned to the medical service.

SETTING

A 241-bed teaching hospital with 55 categorical internal medicine residents.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Over a 4-week period, there were 194 admissions to the medical service on 18 call days preceding MR. Of these admissions, 30 (15%) were presented at MR. Cases were more likely to be presented if they were considered unusual or rare in presentation or incidence ( p = .001), involved significant management issues ( p = .001), or were associated with remarkable imaging studies or other visual material ( p = .006). Residents were more likely to present cases in which they disagreed with attending physicians on management plans ( p = .005). Overall, residents rated few admissions as having notable physical examination findings (29/194) or ethical or cost issues (6/194). Of the seven most common admitting diagnoses, representing 44% of admissions, residents did not present cases involving four of these diagnoses.

CONCLUSIONS

Residents presented cases at MR that they felt were unique or rare in presentation or incidence for purposes of discussing management issues. Complete resident freedom in choosing MR cases may narrow the scope of MR and exclude common diagnoses and other issues of import such as medical ethics or economics.

Keywords: morning report, postgraduate education, internal medicine residency, educational conference

Morning report (MR) is a universal component of internal medicine training.1–3 Though there is wide variation in format, attendance, and timing, all MRs share the common goal of case presentation for purposes of educating resident physicians, monitoring patient care, and reviewing management decisions and their outcomes. As a teaching session, resident physicians rank the educational value of MR higher than other conferences or activities.4

The case mix at MR varies with institution-specific practices and ranges from review of all recent admissions to the selection of cases deemed interesting by the admitting residents, chief residents, or attending physicians. In a recent survey of 286 internal medicine training programs, 75% limited MR presentations to two to four recent admissions, and presented cases were largely selected by the residents themselves.1

Given that the case mix at MR forms the template for discussion of disease-specific etiology, presentation, and management, case choice determines or at least affects the educational value of MR. Frequent criticisms of MR have included its preoccupation with rare cases or cases selectively chosen to showcase sound management or overall knowledge on the part of the presenting residents.5,6 Though previous investigations have detailed resident preferences for the number and type of cases, no reports, to our knowledge, have explored the reasons residents present certain cases and not others in an institution that permits the free choice of MR cases.4

METHODS

This was a prospective study conducted at The Miriam Hospital, a 241-bed teaching hospital affiliated with the Brown University School of Medicine. Morning report is a 1-hour conference that takes place on four weekday mornings. The medical service is organized into five teams, each team composed of two first-year, one second-year, and one third-year resident. Morning report is run by the chief resident and is attended by second- and third-year residents on the medical service. It is attended regularly by the chief of medicine, program director, and two or three general medicine and subspecialty faculty members.

The format of MR is as follows: after a follow-up of recently discussed cases, the postcall residents present one to two patients they admitted during the previous 24 hours. Though the chief resident makes evening management rounds, the admitting residents are free to decide which cases to present.

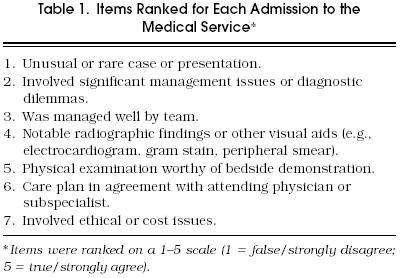

For purposes of this study, the chief resident met with each postcall resident 1 hour before MR and administered a survey designed to determine whether the proposed cases for presentation possessed unique attributes compared to those that were not selected. In deciding which items to include in the survey, we informally queried senior residents on which case characteristics they deemed appropriate or desirable in cases presented at MR and consulted the literature on the same subject.4 Accordingly, residents were asked to rate all admissions on a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree/false; 5 = strongly agree/true) in response to seven items on why they presented certain cases and not others (Table 1). Residents were also asked if cases presented by them involved subject matter related to possible future subspecialty training plans. The time of each admission was documented by consulting a computerized log of all admissions maintained by the medical records department. Survey responses that scored 4 or 5 on the Likert scale were included in the analysis, and survey results for cases presented versus those not presented were tabulated and compared using Student’s t test.

Tabel 1.

Items Ranked for Each Admission to the Medical Service

RESULTS

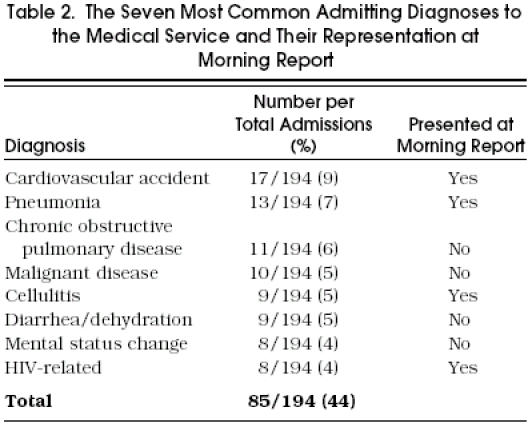

Over a 4-week period, there were 194 admissions to the medical service on 18 call days preceding MR. There was an average of 10.7 (±3 SD) admissions per call day (range 4–16). Of these admissions, 30 (15%) were presented at MR. The most common admitting diagnoses and their representation at MR are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Seven Most Common Admitting Diagnoses to the Medical Service and Their Representation at Morning Report

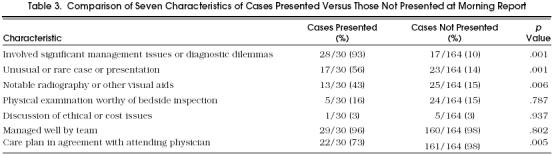

Survey results for cases presented versus those not presented at MR are shown in Table 3. Cases were more likely to be presented if they were considered unusual or rare in either presentation or etiology (p = .001), involved diagnostic dilemmas (p = .001), or were associated with notable radiography or other visual aids (p = .006). Residents were also more likely to present cases in which they disagreed with the attending physician of record on patient management plans (p = .005) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Seven Characteristics of Cases Presented Versus Those Not Presented at Morning Report

Few cases admitted to the medical service were characterized as posing ethical or cost issues (6/194, 3%), or having findings on physical examination worthy of bedside demonstration (29/194, 15%). The subject matter of presented cases did not correlate with resident subspecialty plans.

The time of all admissions was reviewed for 13 call days. Sixty-seven percent of admissions took place between 7 AM and 6 PM and 33% took place after 6 PM. Of 19 presented cases, 17 were from admissions before 6 PM, and 2 were from admissions after 6 PM (p = .008).

DISCUSSION

The results of this survey imply that cases presented at MR share several common attributes. Residents presented cases primarily to discuss diagnostic dilemmas or pertinent management issues. The majority of presented cases were considered either unique in presentation or rare in etiology. Nearly half of presented cases had associated radiography or other visual aids that residents considered worthy of demonstration. Only a small fraction were presented to demonstrate physical findings or discuss ethical or cost issues. These results have many implications for academic internal medicine training programs.

A frequent criticism of MR has been its preoccupation with the dramatic or unusual at the expense of common illness. A comparison of admitting diagnoses of presented cases and not presented cases reveals that MR cases were fairly representative of all admissions with some notable exceptions (Table 2). Of the seven most common admitting diagnoses, four diagnoses (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diarrhea/dehydration, mental status change, and malignancy) were not represented at MR. Cases with these diagnoses received low scores (≤3) on the survey for all items except “agreement with attending physician” and “managed well by team.” Though we did not ask residents to comment on why commonly encountered illnesses were not presented at MR, possible explanations include fear that these cases would be uninteresting or otherwise unattractive for case presentation and discussion. The equation of common with uninteresting is arguable, but equating common with irrelevant is a disservice to the educational process of MR.

A possible approach that would make MR cases more representative of prevalent illness yet preserve resident autonomy would be to allow residents to choose one case but have chief residents choose the second case. The latter may conform to an MR curriculum that would utilize admissions to cover an established list of disease processes thereby broadening the scope of MR and better serving the educational needs of residents. For example, cases in the beginning of the academic year may largely involve basic pathophysiology and management issues important for the starting resident. This system may also prevent duplication of cases at MR. For example, during the study period, cases with diagnoses of cholecystitis, deep-venous thrombosis, and acute renal failure were featured twice at MR. Such an internal monitoring system has been successfully applied at other institutions.3

A notable finding of this survey was resident opinions on what constituted appropriate topics for discussion at MR. With few exceptions, residents presented cases to discuss management issues or diagnostic dilemmas. This may have been due to the institutional custom of MR being a primarily sedentary activity resembling a roundtable discussion. Interestingly, medical residents were more likely to present cases in which they disagreed with the attending physicians on management issues; these ranged from choice of antibiotic to need for diagnostic testing. Although residents presented cases they characterized as posing diagnostic dilemmas, a review of all admissions during the study period disclosed that residents rarely presented patients for whom the diagnosis was uncertain by the time of MR. A retrospective review of presented cases revealed that in all but 2 of the 30 cases, the presenting resident’s MR diagnosis was the same as the patient’s discharge diagnosis.

The time of admission emerged as a major determinant of case presentation. Though 33% of all admissions occurred after 6 pm, these admissions accounted for only 5% of MR presentations. Survey results were not significantly different for admissions before 6 pm and admissions after 6 pm. Reluctance of residents to present evening or late night cases most likely derives from lack of time to adequately prepare these cases for presentation. Our MR’s emphasis on recently admitted cases may narrow the breadth of presentations by emphasizing acute care and allowing only well-thought-out and adequately researched cases to be presented. Encouraging presentations of patients who have been in the hospital or have been recently discharged may lessen this bias and shift some of the focus of MR from acute care to longitudinal or ambulatory care and follow-up.7–9

The survey asked residents to rate their management of cases to determine if only the well-managed cases were presented at MR. The high rate of “managed well” (189/ 194 cases) may have been due to the direct administration of the survey to the residents and their reluctance to admit management errors to the chief residents. The subject or subspecialty matter of MR cases did not correlate with the presenting resident’s postgraduate plans.

The survey’s results indicated that few admissions raised ethical or cost issues. This is in sharp contrast to the departmental bimonthly medical ethics rounds in which residents assigned to the medical wards usually have an overflow of cases they wish to discuss. As the survey asked residents to rate their admissions in the context of MR presentations, the lack of response may well reflect the acute care bias of our MR and the ensuing perception that other issues have no place at MR. Efforts are under way to broaden the subject matter at our MR.

Ideally, MR should be a well-rounded conference that addresses a myriad of issues in a systematic and scholarly manner. Although resident autonomy in choosing cases for presentation is important, it may lead to overrepresentation of unusual cases at the expense of the commonly encountered or selective presentation of cases with known diagnoses instead of cases that are “works in progress.” Emphasis on recently admitted cases may limit presentations to those the resident has had adequate time to prepare and narrow the focus of MR to acute care at the expense of ambulatory or longitudinal care. Though management issues and diagnostic dilemmas emerged as major reasons for presenting certain cases and not others, this was at the expense of other subject matter, such as ethical and economic issues, which if addressed may broaden the scope of MR and enrich its participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schiffman FJ, Mayo-Smith MF, Burton MD. Resident report: a conference with many uses. RI Med. 1990;73:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256:730–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pupa LE, Carpenter JL. Morning report: a successful format. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:897–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report: a survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1433–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeGroot LJ, Siegler M. The morning report syndrome and medical search. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1285–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197912063012311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brancati FL. Morning distort. JAMA. 1991;266:1627. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:395–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wartman SA. Morning report revisited: a new model reflecting medical practice of the 1990s. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:271–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02599886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malone ML, Jackson TC. Educational characteristics of ambulatory morning report. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:512–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02600116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]