Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the comprehensibility of hepatitis B translations for Cambodian refugees, to identify Cambodian illnesses that include the symptoms of hepatitis, and to combine these observations with critical theoretical perspectives of language to reflect on the challenges of medical translation generally.

DESIGN

Open-ended, semistructured interviews, and participant-observation of a refugee community in Seattle, Washington.

SETTING

Homes of Cambodian residents of inner-city neighborhoods.

PARTICIPANTS

Thirty-four adult Cambodian refugees who had each been educated about hepatitis B through public health outreach.

RESULTS

Medical interpreters translated hepatitis B as rauk tlaam, literally “liver disease.” Unfortunately, while everyone knew of the liver (tlaam), rauk tlaam was a meaningless term to 28 (82%) of 34 respondents and conveyed none of the chronicity and communicability intended by refugee health workers for 34 (100%) of the respondents. In contrast, all respondents knew illnesses named after symptom complexes that include the symptoms of acute and chronic hepatitis, but do not refer to diseased organs. The Cambodian words chosen to translate hepatitis B reflect the medical thinking and medical authority that can unintentionally overwhelm attempts at meaningful communication with non–English-speaking patients.

CONCLUSIONS

To improve comprehension of hepatitis B translations for the Khmer, translators must choose between medical terminology focused on the liver and Khmer terminology which identifies recognizable experiences, but represents important Khmer health concepts. A critical linguistic view of this situation suggests that for these translations to be meaningful clinicians and health educators must first analyze and then monitor the contextual significance of medical language. In cross-cultural settings, this means a partnership with medical interpreters to pay close attention to the expe-rience of illness and social context of the translation.

Keywords: Cambodian refugees, hepatitis B, medical language, physician-patient interaction, medical translation

The linguistic transformation was a part of the process of ordering, in armies and schools, architecture and railways, irrigation projects and the production of statistics, which, . . . began to produce what seemed a structure standing apart from things themselves, a separate realm of order and meaning. This new realm . . . would appear not only as the realm of meaning but also as the realm of intentionality—of authority or political certainty.

Timothy Mitchell, Colonising Egypt1

Hepatitis B is endemic in Southeast Asia.2,3There are more than 300 million cases globally,4–6 and chronic hepatitis B infections are the leading cause of hepatoma, the most common type of cancer worldwide.7,8 Ninety percent of the 1 million Southeast Asian refugees now living in the United States have been exposed to hepatitis B. An estimated 100,000 or 10%–15% of Southeast Asian refugees chronically carry the virus in the United States and can pass it to others9,10 For this reason, all Southeast Asian refugees arriving in the state of Washington are screened by the state’s public health department for serologic evidence of exposure to hepatitis B (hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B surface antibody). Refugees that have antibodies to the virus are not recontacted, but persons susceptible to the infection are recalled to the clinic for immunization. Those without antibody, but with evidence of continued production of surface antigen, are chronic carriers of the virus, and are called back for further education.

In Washington state alone there are an estimated 5,000 hepatitis B carriers in the Southeast Asian immigrant population. These chronic carriers of hepatitis B are told by refugee screening staff, soon after their arrival, that they can transmit the virus to others through intimate contact. In addition, chronic carriers are told that, although they may not feel sick, they will need lifelong monitoring to check for evidence of cirrhosis and hepatoma.

The communication of health information with a behavioral component must be particularly clear and persuasive if the recipients are expected to register and remember the message, and then act accordingly. Pamphlets are routinely used by refugee health programs to communicate the hepatitis B message to carriers and their families. Often refugees cannot read; in this event an interpreter reads and explains the content of the pamphlet to them. The pamphlets contain very basic information about the viral cause of hepatitis, its communicability, and the behaviors to be avoided to prevent viral transmission, such as sharing a toothbrush, donating blood, and unprotected intercourse.

Language is a fundamentally human activity through which people negotiate relationships and community life. It is also a fundamental technology in medicine, a principal instrument for conducting work. This dual role of language as both a social tie and technical instrument can contribute to misunderstandings between physicians and patients. Such misunderstandings routinely occur when a patient and provider speak a common language but they may be even more pronounced when a clinical interaction must be negotiated through translation.

The objectives of this study were to determine if public health translations of hepatitis B information were meaningful to Cambodian patients, to explore Cambodian understandings of illness associated with hepatitis-like symptoms, and to subject our empirical findings to a linguistic critique, addressing theoretical questions about medical language and how it structures physician-patient communication.

METHODS

Participants

Thirty-four ethnic Khmer men and women participated in the study; 23 were men and 11 were women. All of them lived in Cambodia until at least 18 years of age, and relocated to Washington state from the Thai border camps after 1984. The participants were raised in both rural and urban ares in various provinces of Cambodia, and represent a cross section of socioeconomic groups. An interpreter and one of the authors (JCJ) interviewed a random sample of 18 people immune to hepatitis B, a convenience sample of 10 chronic carriers of the virus, and an intentional sample of 6 persons with symptoms of active liver disease. Respondents ranged between 24 and 70 years of age. Four traditional healers were included in our sample. Participants were identified using refugee screening records of the King County Department of Public Health, and the active cases of hepatitis were identified through Harborview Hospital medical records.

Interpretation

We selected two interpreters, one male and one female, to cross-check one another. Both were older adults who were raised to adulthood before the revolutionary period in Cambodia and were familiar with both urban and rural Cambodian life and language use.

Interviews were interpreted in a paraphrased manner with latitude for the interpreter to expand information when appropriate. A principal interpreter was selected, and the second interpreter reviewed randomly selected excerpts of the principal interpreter’s interviews to guarantee adequacy of interpretation.

Interviews

The refugees were interviewed in a semistructured conversational manner. All interviews were audiotaped; each lasted approximately 2 hours. Respondents were asked if they had ever heard the standard terms used to translate hepatitis B into Khmer, and what associations, if any, they had with those terms. The interviews then progressed to discuss common symptoms (e.g., jaundice, fatigue, malaise, and ascites) associated with acute and chronic hepatitis. Respondents were asked about people they knew who had these or related symptoms and how they were diagnosed and treated. Case histories of acute and chronic hepatitis were presented to individuals and focus groups, and they were asked to comment on possible Cambodian diagnoses, etiologies, and treatments. Ten respondents were particularly knowledgeable and informative; these people were recontacted a second and, occasionally, a third time to cover other topics or go further in-depth on an issue. There were three focus groups in which respondents were interviewed in groups of six to eight to review, interpret, and validate study results.

Analysis

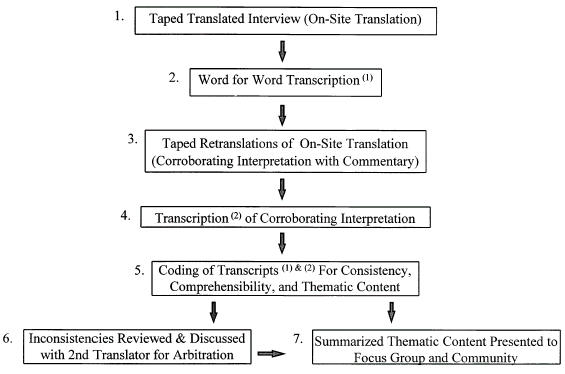

The English portions of the interviews were transcribed word for word from audiotape. The interview was then compared with these transcripts by the principal interpreter and the original interviewer to discuss and clarify confusing nonsequiturs, word choices, and miscommunications in the translation between English and Khmer. A second, English-only translation (the corroborating interpretation) incorporating these corrections was audiotaped and transcribed. Interviewees were contacted if necessary to clarify a word or point or to provide contextual information with necessary geographic, linguistic, historical, and cultural annotation. The second, corroborating transcripts were later reviewed for accuracy by the interpreter and one of the investigators (JCJ). The initial translation and corroborating interpretation transcripts were available for comparison, and were reviewed by the interpreter and interviewer for content and predominant themes. Any questions arising from the analytic interpretations were referred to the second interpreter for comment and arbitration. The method is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Interview methods.

Analysis was continuous during the period of the interviews. In this study we identified definitions and experiences associated with key words. Information retrieved during one encounter was reviewed by the interview team. Terms and concepts learned during one encounter were explored further with different respondents during subsequent interviews. Once an idea or phrase was repeated by two or three subsequent respondents, it was taken as a lead-in point, so that subsequent discussions did not repeat well-established information but could go further into nuances, implications, and troubling contradictions of established concepts. Our findings were later summarized and reviewed in focus group settings and with other community members for accuracy of interpretation and comment.

RESULTS

The Language of Hepatitis in Public Health Translations

All Cambodian hepatitis B pamphlets in Khmer, the principal Cambodian language, used the term liver disease (rauk tlaam), or swollen liver disease (rauk hoem tlaam) as the translated expression of “hepatitis B.” When asked why rauk tlaam was chosen as the appropriate Khmer translation for hepatitis, translators explained that this phrase best captures the organ damage expressed by the medical Greek word, “hepatitis.” The distinction “B” was routinely dropped and considered unnecessarily confusing.

During interviews, however, we found that rauk tlaam was a meaningless phrase to 28 (82%) of the 34 Cambodian respondents. This included persons with active hepatitis who had evidence of liver damage. We found that only two of the six subjects that had active hepatitis recognized the term “liver disease.” Another four subjects (one carrier and three noncarriers) had heard the term. Before leaving Cambodia, while receiving treatment as patients in French clinics there, 3 of the 34 persons interviewed had heard the term rauk tlaam, and remembered that it was associated with heavy alcohol use. However, these three subjects could not describe what having a liver disease might mean or feel like. Three other refugees learned about rauk tlaam several years after their arrival in the United States (and initial screening), two when they became symptomatic with active hepatitis.

Except for these few subjects who had heard the term in Western clinics, the respondents had no conceptual or experiential associations made with the liver or with liver illness, with one significant exception: rashes were associated with liver problems. All 34 respondents mentioned a benign self-limited rash, called korn teal tra’ak, thought to be caused by a “weak” liver. This term describes papular erythematous rashes including hives. Korn teal tra’ak was repeatedly referenced in any discussion of illness related to the liver, and often was assumed to be synonymous with the term rauk tlaam, or liver disease. Although no one could explain how the liver caused or was otherwise involved with the rash, nearly everyone recalled that they learned of the relation between rashes and weak livers from their parents and grandparents. There was no other identifiable significance of the liver to Khmer notions of health and illness. There was also no detectable difference in knowledge about hepatitis B between those who were immune, those who were carriers, and those who had active disease, and so their interviews were pooled for analysis.

The Language of Hepatitis in Cambodian Communities

Naming illness after affected anatomic parts or physio-logic processes, such as meningitis or heart failure, is essential to organizing Western medical diagnoses. When asked about the liver, many of the Cambodians were quick to say, “We don’t know what the liver looks like when it’s sick; never see that; we never see the sick person’s liver.” It is not a Cambodian practice to organize illnesses by organ systems. Rather, illness is categorized descriptively by the symptoms experienced, and ascribed to causes determined by the patient, the family, or a traditional healer.11,12 As such, an illness might be ascribed to bad food, loss of internal balance, dishonoring an ancestor, excessive hard work, witchcraft, karma, taboos, or violating prescribed behaviors.13,14

Yellow Illness or Khan Leoung

When examples of jaundice, fatigue, anorexia, and abdominal discomfort were ascribed during the interviews, every Cambodian respondent readily identified the symptoms of what medicine would designate as a hepatitis-like illness by these names: Khan leoung (yellow illness), tloeak andoek (the turtle falls [oranomegaly]), and occasionally other illnesses such as ampeau (swollen stomach), ka trok or ruis daung bhat (the root of the coconut, or hemorrhoids). All of the respondents were familiar with khan leoung or “yellow illness.” Beyond the obvious jaundice, some reported other symptoms as part of this illness: pallor, fatigue, anorexia, malaise, pica, wasting, and amenorrhea. Often self-limited in the young, khan leoung can be recurrent, chronic, and even fatal in adults.

A 37-year-old man who now has chronic active hepatitis B recalled being told he had rauk tlaam (liver illness). He learned this term after he had been hospitalized for vague abdominal pains, and during subsequent follow-up visits in a clinic. At the time of interview he still did not understand why he had been hospitalized, or what liver illness (rauk tlaam) means, what it is caused by, feels like, or how it is transmitted. However, when asked if he had ever known someone with yellow illness (khan leoung), he exclaimed immediately,

“My mom got khan leoung and die by it. She used to use the betel and kombow [lyme], you know to put in the betel and chew it . . . most people chew it and spit it, but my mom swallowed it when she got this khan leoung. I know people who got khan leoung and wanted to eat charcoal or ashes from cigarettes, but my mom chewed betel. She used to treat it by taking iron slag from the blacksmith and put it in palm water, and then the palm water become sour, and she drink it. The Kru (traditional healer) told her to do this. It become cured, little bit cured, but after come back.”

Organomegaly or Tloeak Andoek

Pain and swelling in either the left or right upper abdominal quadrants was described by the metaphor tloek andoek, literally translated, “the turtle goes down” or “the turtle falls.” This metaphor was mentioned often in a discussion of chronic illnesses with abdominal swelling and fever. For example, a 57-year-old man was asked if he had ever heard of liver illness (rauk tlaam). He responded, “No, we don’t know that because the Cambodian Kru (healer) cannot see that . . . we know just tloek andoek, something here at the right side, at the rib go down from the rib. It comes with very long fevers.”

This illness was also accompanied by malaise, fatigue, low-grade fever, wasting, and at times, prominent abdominal veins. Tloek andoek is usually considered a sequela of prolonged fever, such as malaria. Subjects were reluctant to say which organ is swollen, but they pointed with confidence to the left or the right upper quadrants where the swelling can be felt. They were also certain that tloek andoek can run a long course, is associated with wasting, swollen abdomen, malaise, recurrent fever, and is often fatal.

Several illnesses were mentioned by fewer interviewees, but these were also associated with the symptoms of hepatitis. The four Kru Khmer (traditional healers) interviewed each discussed ruis daung bhat, or hemorrhoids, as well as khan leoungtloek andoek. In our discussion, these traditional healers explained that mild hemorrhoids are of little concern, but that hemorrhoids in the presence of other systemic features of illness indicate a severe problem, and in this setting ruis daung bhat is associated with jaundice, abdominal swelling, and prolonged and often terminal illness. Although these Cambodian illnesses each describe in detail the experience of acute liver inflammation and chronic liver failure, they are clearly not identical to viral hepatitis. Tloek andoek, for example, may be ascribed to liver enlargement in one person and splenic enlargement in another. We did not find a Cambodian equivalent of viral hepatitis, with the anatomic and etiologic specificity that is typical of biomedical diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Educating non-Western immigrant groups about important biomedical concepts is one of the challenges of clinical medicine in many large medical centers across the country. We found that in this case, the direct translation of “hepatitis” into Cambodian as “liver disease” suggested a benign rash to most of our respondents. However, we found that the experience of liver failure is recognized and understood by many Cambodians according to taxonomies of illness unacknowledged in public health pamphlets. Chronic carriers of hepatitis B who had been contacted and educated about hepatitis B, including the six respondents with active liver disease, knew more about the Cambodian illnesses khan leoungtloek andoek than about hepatitis B or rauk tlaam.

These findings raise important questions about the quality of interpretation, translation, and patient education occurring in many clinical settings. Precise translations of medical terms may be meaningless to speakers of other languages. Optimum interpretation and patient education occurs when time and effort is spent on cultural mediation around critical concepts. Although this can require out-of-clinic dialogue between interpreters and clinicians, it allows each to negotiate cultural concepts so that common phrases and experiences can be identified, such as khan leoung.

Cambodian concepts may admittedly imply behaviors and treatments unintended by clinicians, but this common ground may be a more meaningful place to begin patient education. From this place, new information may be added to old concepts, and clinicians can be alerted to the cultural implications of translated terms. These findings are applicable to older Cambodian immigrants, although the general lessons learned in this hepatitis B study are also applicable to translations for tuberculosis, HIV, and cancer prevention.

Medical Linguistics and Medical Translation

Translating words and actions between the technical world of medical thought and the everyday lives of people is the daily challenge of clinical practice. In many ways the Cambodian case of hepatitis B is a more extreme example of what happens between doctors and patients, and even between physicians from different specialties, on a daily basis in medical practice. These findings illustrate three theoretical observations about medical language of practical significance for physician-patient communication in general.

Words Link Concepts to Experience

Rauk tlaam was the organizing focus of the Cambodian translation because hepatitis is a key word associated with many important concepts for medical professionals. However, the choice of rauk tlaam as the appropriate Cambodian equivalent highlights important differences between medical language and everyday speech relevant for English and non-English speakers alike.

Medical words shape meaning by valuing physiologic processes over social experiences. For example, physicians taking a history silently restructure patient experience into symptom complexes by means of specialized language, using words like orthopnea, angina, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. These words are conceptually linked with the words of diagnosis and treatment in a semantic network that is the linguistic basis of clinical activity. Without losing track of the person, physicians attempt to understand an experience of illness and give precedence to well-recognized expressions consistent with known disease processes over idiosyncratic experiences incongruent with clinical reasoning. Once the patient’s experience has been reconfigured according to a medical paradigm, as one word evokes another, a physician can find his or her way along the semantic pathways to the implied evaluation and treatment algorithms.

For lay people, language and behaviors are linked in entirely different ways. This is particularly evident when physician and patient are from cultures in which drastically different meanings are implied by words. Traditional Cambodian illness terms are associated with an intricate web of natural forces, supernatural beings, family life, social obligation, and karmic law. For example, illness terms associated with the accumulation of wind, or kyol, imply dermabrassive application of coins to release wind. Other illnesses evoke rituals and obligations for ancestor care, behaviors to ward off witchcraft, charitable actions to address the laws of karma, or the therapeutic use of herbs. The culturally defined knowledge and social practices of Cambodian people link their experience through language to an implied set of behaviors.

For the Cambodian patients, the words for liver illness link conceptually to a benign rash with virtually no behavioral consequences, while for the physician hepatitis is a communicable illness with implications for sexual intercourse, blood donation, dietary habits, and regular medical follow-up. In contrast, Khmer illnesses like khan leoung lack the specificity of a medical diagnosis and its implications, but overlap the recognized symptoms of hepatitis.

Context Determines Behaviors Implied by a Word

Translation has been described as a process of finding equivalent verbal structures while recognizing significant cultural variations in their uses and meanings.14 Interpreters struggle to find these equivalents when translating. These are easier to find if the language groups share a common linguistic base and cultural history, such as within the Indo-Aryan–based European languages. But if linguistic structure and daily practices differ significantly, then equivalent words and experiences may not exist.

Translating hepatitis B information for Cambodian populations poses challenges in finding vocabulary, conceptual, and experiential “equivalence.”15 Vocabulary equivalence entails finding a word in one language with the equivalent nuances and connotations of a word in another. Often there are no vocabulary equivalents. English often adopts terms precisely for this reason (like potlatch, taboo, and sitar). The term rauk tlaam is a good example of a Khmer vocabulary equivalent invented for hepatitis. Beginning with an organ-based model of illness, an attempt has been made to convey this anatomic view of hepatitis to the Khmer by creating a verbal counterpart focused on the liver. We found that this approach met with limited success in the population we studied.

Conceptual equivalence refers to the multiple associations of certain words. As in poetry, the values associated with a word, its linkage to other words, and the implications of its use in that culture are its conceptual associations. For example, in English, “heart” refers to an organ, the seat of emotion, a person’s character, (as in “cold-hearted” or “lion-hearted”), and the core of an issue (as in “the heart of the matter”). Because conceptual associations are steeped in history and usage, conceptual equivalence in translation is nearly impossible. For historical reasons unknown to our informants, there remains in Cambodian culture a conceptual link between various skin rashes and a “weak” liver.

Experiential equivalence means that a word or phrase must refer to real things and experiences familiar to both cultures. The association of a word with specific experiences links that word in socially and conceptually unique ways for the groups that share that language. In medical translation experiential equivalence can often, although not always, be found in bodily symptoms. For example, although jaundice does not have the same meaning as khan leoung, and organomegaly is not exactly tloek andoek, the bodily experiences do overlap significantly, and this is a more concrete place to begin discussion than with a vocabulary equivalent of a biomedical concept.

In addition to finding linguistic equivalence, moving from experience and conceptual linkages to implied actions or behavioral changes in a cross-cultural conversation requires that special attention be paid to the referential and performative values of words. The referential value of a word means that the word refers to some element or concept within the speaker’s world. This is the notion of a word as a symbol for an idea or thing. But words can also communicate requests for action. The performative value of a word implies that the use of a word will imply specific behaviors in a given context.16 For example, the sentence “There is a bear” may imply entertainment and education at the zoo or a move toward safety in the mountains. In both contexts the referent may be the same, but the performative value is markedly different. Keeping track of the reference and its implied activities in a given context is an extremely difficult task when people do not share the same daily activities and realities.

Consider the sociolinguistics of the medical profession, in which daily practices vary drastically according to specialty, and each specialty develops unique referential and performative associations with words. Jucovy surveyed pathologists and found that the pathologists he interviewed limited their use of the word dysplasia when reporting to surgeons because of the severe performative implications for surgeons when dysplasia was mentioned.17 This is true of other routine communication failures between specialists that occur on a regular basis. The frustration sometimes encountered in consultation, for example, between surgeon and pediatrician or radiologist and internist, can often be attributed to dialectic differences in medical speech. Jucovy suggests that medical speech is really a “pidgin” language, that is a language shared for working purposes between divergent groups who use languages unique to their cultural settings, e.g., radiology, pathology, epidemiology, or surgery.

The importance of the performative value of words is central to health education efforts. The authors of the hepatitis B pamphlets intended to link the experience of hepatitis to requests for changes in behaviors from Cambodian immigrants, behaviors such as the routine use of condoms. Unfortunately, the referential value of rauk tlaam was at best meaningless, and at worst confused with a rash (korn teal tra’ak). Consequently, the performative implication is similarly meaningless. Conversely, the use of known references (like khan leoung) may imply unintended actions, such as a visit to a traditional herbalist.

Language Expresses Both Knowledge and Social Status

Greek and Latin roots are used in medical terminology for historical reasons rooted in the Western scholastic tradition. These classical languages also allow for easy recombination of suffixes and prefixes that make subtle distinctions possible. Newly coined medical words are intended to be a part of a universal language of medicine that refers to biologic processes. Medical interpreters can be preoccupied with this precise language and the sophisticated interpretation it requires, and lose track of their audience. Similarly, clinicians who speak medical language fluently may rely on medical speech exclusively. In doing so, they can lose track of whether they are in the biologic reality or the socially situated reality of a patient’s daily life. For clinicians medical words may imply risk to the health of the biological body, but not acknowledge related risks to the social body.

Cambodian experiential and conceptual equivalents were not considered in the initial translations of hepatitis B information because of the goal of giving information of universal importance about the liver and the assumption that the uniquely Cambodian experience of illness was minimally important. All the translators interviewed knew that rauk tlaam was a meaningless term to most Cambodians. When conceptual and experiential equivalences are impossible, the translator must choose whose cultural reality to express; at that point, social status determines whose referential and performative worlds will shape the translation. The interpreters expressed that professionally their first allegiance was to the medical system that employed them to send a message. The asymmetry of knowledge and status clearly determined (at least for the interpreter) whose reality should be conveyed when one is unable to find conceptual and experiential equivalence. The view of language as a referential window to a biological structure predisposes the speaker, and consequently the interpreter, to focus on the structure of disease rather than the experience of disease as an organizing principle; therefore the interpretation concentrates on presumed universals through vocabulary and concept, and eclipses cultural experiences as particularistic and subjective.

Medical language attempts to order experience and set the structural features of a disease apart from the individual who has experienced that disease. Meaning, authority, and certainty lie in the scientific conceptual features of disease that stand apart and supersede the personalized experiential features of illness. The process of sorting the subjective from the objective through the use of medical terms has the unintended effect of deciding what is “important” and what is “superfluous” in an individual’s (and culture’s) experience of illness, decisions that do not necessarily coincide with what that patient or group of patients thinks is important about their illness.

Khmer medical interpreters have expressed their frustration to us in trying to explain this “unseen, unperceived” structure of disease to Khmer patients who identify an illness based on the experience of that illness. Diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and hepatitis B are especially difficult because they may be asymptomatic for long periods of time; during asymptomatic periods, when the patient feels fine, clinicians insist that disease and disorder are present but the patient has no experience of either.

Practical Implications

The practical implications of these three theoretical observations illustrated by our study suggest that: first, unless interpreters and public health educators are given special instructions to interpret culturally meaningful information, hepatitis translations will continue to focus on vocabulary equivalents of disease that are anatomically correct, but meaningless to many non-Western groups; second, clinicians and public health workers should form partnerships with interpreters to identify key vocabulary, experiences, and concepts that will educate clinicians about the meaning and experience of common illnesses in immigrant communities and will help health workers shape their educational efforts; and third, health professionals in patient education must have better training to choose words appropriate for audience and context, be it professional or lay, Western or non-Western.

New information can and must be introduced into existing frameworks of health and illness, but this can be done in a meaningful way only when information about the target audience is retrieved first and then incorporated into the clinical message to be sent.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the important contribution of Lysieng Ngo, Phalla Kith, and Warya Pothan to this effort. We especially acknowledge the central role of Oung Hieam to our work. We were saddened by his death and will remember his wisdom and gentle instruction. We are grateful to Judy Sanders for assistance with preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitchell T. Colonising Egypt. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press; 1991. pp. 128–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conjeevaram HS, Di Bisceglie AM. Management of chronic viral hepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:365–75. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill LL, Hovell M, Benenson AS. Prevention of hepatitis B transmission in Indo-Chinese refugees with active and passive immunization. Am J Prev Med. 1991;7:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, et al. Incidence of hepatitis B virus infections in preschool children in Taiwan. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:198–204. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman RA, Benenson MW, Scott RM, Snitbhan R, Top FH, Jr, Pantuwatana S. An epidemiologic study of hepatitis B virus in Bangcock, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:213–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson R, Hoang G. Health problems among Indo-Chinese refugees. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:1003–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.9.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz ME. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma: transplant versus resection. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:135–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rustgi VK. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. In: Di Bisceglie AM, moderator. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:390–401. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lok ASF, Lai CL. Acute exacerbations in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Incidence, predisposing factors and etiology. J Hepatol. 1990;10:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks AL, Berg CJ, Kane MA, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection among children born in the United States to Southeast Asian refugees. N Engl J Med. 1989;231:1301–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoang GN, Erickson R. Cultural barriers to effective medical care among Indochinese patients. Annu Rev Med. 1985;36:229–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.36.020185.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchwald D, Panwala S, Hooton TM. Use of traditional health practices by Southeast Asian refugees in a primary care clinic. West J Med. 1992;61:508–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muecke M. Caring for Southeast Asian refugee patients in the USA. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:431–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.4.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meuecke MA. In search of healers—Southeast Asian refugees in the American health care system. West J Med. 1983;139:835–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sechrest L, Fay TL, Hafeez Zaidi SM. Problems of translation in cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cultural Psych. 1972;3:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin JL. In: How To Do Things with Words. Urmson JO, editor. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1965. In. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jucovy PM. Developing a critical model for diagnostic language. In: Proceeding Medcomp ‘82—First IEEE Computer Society International Conference on Medical Computer Science/Computational Medicine. 1982:465–89. [Google Scholar]