Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii is a causative agent of cryptococcosis and is thought to have a specific ecological association with a number of Eucalyptus species in Australia. However, the role that the tree plays in the life cycle of the fungus and the nature of the infectious propagule are not well understood. This study set out to examine whether sexual recombination is occurring in a natural population of C. neoformans var. gattii and whether the fungus disseminates between colonized trees. Thirty C. neoformans var. gattii isolates, consisting of both the α and a mating types, were collected from 13 Eucalyptus camaldulensis trees growing along a riverbank in Renmark, South Australia. The genetic diversity within the population was studied by using amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting, and each isolate was assigned a unique multilocus genotype. Population genetic analyses of the multilocus data found no evidence of genetic exchange between members of the population, indicating a clonal population structure. Canonical variate analysis was then used to study the relationship between isolates from different colonized trees. Isolates from individual trees were strongly correlated, and it appeared that dispersal between trees was not occurring to any appreciable extent. These results suggest that the eucalypt may not be the primary niche for C. neoformans var. gattii but that the decaying wood present in hollows on these trees may provide a favorable substrate for extensive clonal propagation of the yeast cells.

The worldwide significance of fungal infections has increased dramatically since the 1980s, due to both the rising numbers of immunosuppressed patients, in particular those infected with human immunodeficiency virus, and the limited availability of antifungal treatments. As a result, understanding the epidemiology, mode of reproduction, and pathogenic features of these disease-causing organisms is becoming increasingly important for both the prevention of fungal infections and the development of antifungal treatments and vaccines.

Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii is a basidiomycetous yeast and, along with the closely related Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans, is the causative agent of cryptococcosis, a rare but potentially serious disease of humans and animals (10). Unlike C. neoformans var. neoformans, which is found worldwide, C. neoformans var. gattii is restricted predominantly to tropical and subtropical climates and has been proposed to have a specific ecological association with a number of Eucalyptus species, particularly Eucalyptus camaldulensis (river red gum) and Eucalyptus tereticornis (forest red gum) (12, 35). These trees are native to Australia, where a relatively high incidence of cryptococcosis due to C. neoformans var. gattii occurs in some native animals and indigenous human populations. The trees have also been extensively exported to other tropical and subtropical parts of the world, and colonization by C. neoformans var. gattii has been seen at some of these locations.

Cryptococcal infections are believed to follow inhalation of the airborne infectious propagule from an environmental source and failure of the host defense system to contain the organism in the lung (11, 30). While the nature of the infectious propagule is still unknown, it is assumed to be either a desiccated yeast cell (<2-μm diameter) or basidiospore (1- to 3-μm diameter). Both of these cells are small, dry, and light and should be more readily deposited in the alveoli of the host than the larger encapsulated yeast cell (3- to 8-μm diameter) (10, 25, 38).

Although the association of C. neoformans var. gattii with the eucalypt host has been known for over a decade, the specifics of this relationship remain largely unresolved. Viable yeast cells have been found in the woody debris and detritus associated with Eucalyptus trees, and one study found an apparent correlation between the flowering of the trees and dispersal of the fungus through the air (11). However, it is not known whether the fungus completes its life cycle on the tree, to be shed as basidiospores, or whether it propagates asexually and is dispersed as desiccated yeast cells or asexual basidiospores via haploid fruiting. Clearly, determining the occurrence of the fungus on the host trees and its dispersal from the trees is important for ascertaining the risk of exposure to an infectious propagule. In addition, understanding the prevailing mode of reproduction of a pathogen has important implications for research into the organism and for the diagnosis and management of the disease, as control strategies differ according to the mode of reproduction (41).

A clonal population results when sex is absent or negligible, as might happen, for example, if conditions promoting sexual union do not occur or if one mating partner is absent. Such a population could consist of a single clonal lineage or many different lineages. In a recombining population, asexual reproduction may still predominate but the clonal structure is disrupted by the swapping of genes between members of different clonal lineages. Most fungi reproduce very effectively by asexual propagation but retain the ability to sexually recombine, as this conveys a number of advantages: (i) sex enables the organism to adapt more quickly to environmental challenges, (ii) it allows advantageous gene combinations to be formed more rapidly than in asexual populations, and (iii) it allows the organism to eliminate deleterious mutations that could otherwise accumulate in asexual clones (33, 34).

As the capacity for sexual recombination often coexists with enormous asexual reproduction in fungal populations, the relative importance of sexual recombination in the fungal life cycle is difficult to assess. In recent years, studies have turned to assessing nucleic acid variation to determine how fungal populations reproduce in nature (40). These studies have shown that the observed life cycle of a fungus is not necessarily predictive of the mode of reproduction. Both Coccidioides immitis and Aspergillus flavus have no known sexual life cycle; however, population genetic studies which used sequence comparisons and multilocus genotype data have found that recombination occurs in these species (5, 13, 16).

Mating in C. neoformans is determined by a single-locus, two-allele system, with the two mating types designated MATα and MATa (23). In C. neoformans var. neoformans, the α mating type outnumbers its a counterpart in both clinical and environmental isolates (24, 31). In the C. neoformans var. neoformans A serotype, which is the serotype responsible for the majority of cryptococcosis cases worldwide, the a mating type is extremely rare and, until recently, was thought to be extinct (29, 44). This bias in mating type ratios has been postulated to be due to haploid fruiting of MATα cells, which cannot occur in MATa cells. In this process, haploid α yeast cells are able to form extensive hyphae in the absence of the opposite mating type, producing blastospores and basidia bearing viable basidiospores that are all of the α mating type (47). For C. neoformans var. gattii, both mating types have been collected from the same environmental niche (19) and haploid fruiting does not appear to result in the production of asexual basidiospores (47). It is therefore thought that sexual recombination may be important for the dissemination of this fungus.

The present study set out to determine whether sexual recombination is occurring in a natural population of C. neoformans var. gattii and whether the fungus disseminates between colonized trees in a limited geographic area. Preliminary results from a previous survey found the two mating types to occur on a stand of E. camaldulensis trees in Renmark, South Australia, indicating the potential for sexual recombination in this region (19). Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) fingerprinting was used to estimate the amount of genetic variation within the population and to indirectly analyze the population to determine the relative contributions of sexual and asexual recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tree and air sampling for C. neoformans var. gattii.

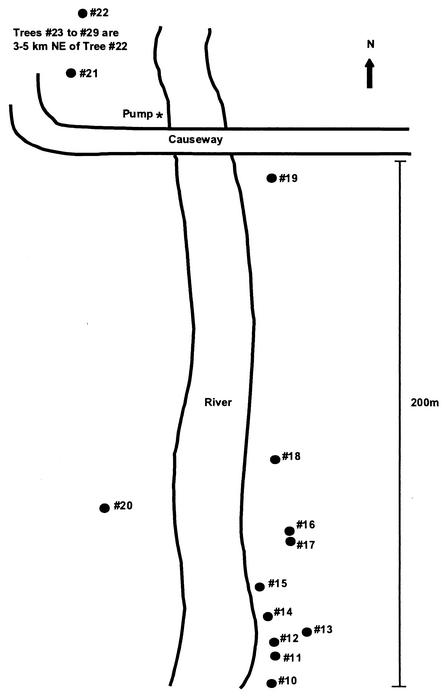

Twenty different E. camaldulensis trees along a 2-km stretch of river bank in Renmark, South Australia (34°11′S, 140°45′E), were sampled for C. neoformans var. gattii in April 1999. Trees with large hollows containing decomposing wood were selected for investigation. Thirteen of the trees (trees 10 to 22) were located along approximately 200 m of riverbank (Fig. 1), and the remaining 7 trees (trees 23 to 29) were located 2 to 3 km northeast of the first trees along a creek bank.

FIG. 1.

Map of riverbank in Renmark showing location of trees (•) that were sampled for C. neoformans var. gattii in 1999.

Sterile swabs (Interpath Services Pty. Ltd.) were moistened with phosphate-buffered saline and brought into contact with areas of interest on the tree, including the internal surfaces of tree hollows, detritus, and the underside of the bark. The air immediately beneath the trees was also sampled for C. neoformans. Air samples were collected (100 liter/min for 10 min) directly onto birdseed agar plates (37) with an Air Sampler MAS 100 (Merck).

Birdseed agar (37) was used for the initial selective isolation of C. neoformans from the environment. Isolates were tentatively identified as C. neoformans by colony morphology, the ability to grow at 28 and 37°C, microscopic morphology of round-to-ovoid encapsulated yeast cells when stained with India ink, and the ability to produce urease. Isolates were then sent to the Australian National Reference Laboratory in Medical Mycology for confirmation of presumptive identification and the determination of the variety by growth on CGB (l-canavanine, glycine, 2-bromothymol) agar. Following purification, the isolates were grown and subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (amyl media) for 48 h at 25°C for DNA extraction.

C. neoformans var. gattii population.

Thirty isolates collected from 13 E. camaldulensis trees in Renmark were chosen as the Renmark population to be analyzed. This consisted of 14 a and 16 α mating type strains, which were selected from as many different hollows and trees as possible to reduce the chance of sampling clonemates. Isolates of different mating types that were present on a single tree were particularly targeted. Isolates R1 to R23 were collected in April 1999, and isolates R24 to R30 were collected by Mark Krockenberger (Department of Veterinary Anatomy and Pathology, University of Sydney) on a previous field trip to Renmark in July 1998. Details of the 30 isolates are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Isolates included in the Renmark population

| Isolate | Tree | Location on tree | Mating type |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 10 | Hollow | α |

| R2 | 11 | Hollow | a |

| R3 | 13 | Hollow 1 | a |

| R4 | 13 | Hollow 1 | a |

| R5 | 13 | Hollow 1 | a |

| R6 | 13 | Trunk | a |

| R7 | 13 | Hollow 2 | α |

| R8 | 13 | Hollow 2 | α |

| R9 | 13 | Hollow 2 | a |

| R10 | 14 | Hollow | a |

| R11 | 14 | Hollow | α |

| R12 | 19 | Hollow 3 | α |

| R13 | 19 | Hollow 4 | a |

| R14 | 19 | Hollow 2 | a |

| R15 | 20 | Hollow 2 | a |

| R16 | 20 | Hollow 3 | α |

| R17 | 20 | Hollow 4 | a |

| R18 | 20 | Hollow 1 | α |

| R19 | 20 | Hollow 1 | α |

| R20 | 22 | Hollow 2 | α |

| R21 | 22 | Hollow 1 | α |

| R22 | 23 | Hollow 3 | α |

| R23 | 23 | Hollow 1 | α |

| R24 | B | Hollow | a |

| R25 | B | Ground | α |

| R26 | F | Bark | α |

| R27 | F | Hollow | a |

| R28 | I | Hollow | α |

| R29 | J | Hollow | a |

| R30 | N | Trunk | α |

DNA isolation.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from approximately 0.75 g (wet weight) of yeast cells, based on the Novozyme 234, dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide, and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide method described by Wen et al. (46). Modifications to the extraction technique were as outlined previously (19). The DNA extraction yielded approximately 2 to 5 μg of DNA/ml, which was diluted 1:10 for PCR amplification.

PCR coamplification with the MFα and STE20aSF primers.

The MFα (MFαU and MFαL) (19) and STE20aSF (STE20aSFU and STE20aSFL) (18) primers were used in a coamplification reaction to amplify a 109-bp fragment from α mating type strains and a 219-bp fragment from a mating type strains. The primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primer and adapter oligonucleotide sequences

| Primer or adapter oligonucelotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| Mating type primers | |

| MFαU | TTCACTGCCATCTTCACCACC |

| MFαL | TCTAGGCGATGACACAAAGGG |

| STE20aSFU | TCCGATTGCTGCGATTTGCC |

| STE20aSFL | GCGCCTGCACCATAATTCACC |

| EcoRI adapters | |

| EA1 | CTCGTAGACTGCGTACC |

| EA2 | CATCTGACGCATGGTTAA |

| Msel adapters | |

| MA1 | GACGATGAGTCCTGAG |

| MA2 | TACTCAGGACTCAT |

| Preamplification primers | |

| EcoRI-C | GACTGCGTACCAATTCC |

| EcoRI-G | GACTGCGTACCAATTCG |

| EcoRI-T | GACTGCGTACCAATTCT |

| Msel-C | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAC |

| Msel-G | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAG |

| Msel-T | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAT |

| Selective primers | |

| EcoRI-CA | 6 FAM-GACTGCGTACCAATTCCA |

| EcoRI-GT | 6 FAM-GACTGCGTACCAATTCGT |

| EcoRI-TG | 6 FAM-GACTGCGTACCAATTCTG |

| Msel-CA | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACA |

| Msel-GA | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAGA |

| Msel-GT | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAGT |

| Msel-TG | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAATG |

Sequences are 5′ to 3′, except for those of EA2 and MA2, which are 3′ to 5′.

PCR amplifications were performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 1× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin), 5% glycerol, 6.25 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer (MFαU, MFαL, STE20aSFU, and STE20aSFL), 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 1 μl of diluted template DNA. Amplification conditions for PCR were 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. All amplifications were carried out in a Perkin Elmer 2400 Gene Amp PCR system.

A total of 10 μl of each amplification product was electrophoresed at 10 V/cm and 40 mA in 2% agarose gels made in 1×Tris-borate-EDTAbuffer and containing 0.5 ng of ethidium bromide/ml. The gels were visualized by UV transillumination and photographed.

AFLP.

The AFLP fingerprinting protocol was based on the technique described by Vos et al. (45). Twenty microliters (200 to 600 ng) of genomic DNA was digested with 5 U (each) of the EcoRI (Boehringer Mannheim) and MseI (New England BioLabs) restriction enzymes for 2.5 h at 37°C. To check that complete digestion was obtained, 10 μl of the digestion reaction mixtures for some isolates were transferred to another tube and 50 ng of lambda DNA (MBI Fermentas) was added before the tubes were incubated. Following digestion, these reaction mixtures were run on a 1% agarose gel to check for complete digestion of the lambda DNA.

After digestion, EcoRI and MseI double stranded-adapter sequences (Table 2) were ligated to the sticky ends of the restriction fragments at 22°C for 3 h. After ligation, the reaction mixture was diluted 1:7 in distilled H2O and stored at −20°C for later use in AFLP PCRs.

The AFLP preamplification and selective amplification reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl. Each reaction mixture contained 1× PCR buffer, 20 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 μM concentrations of the appropriate EcoRI and MseI preamplification primers or selective primers, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 5 μl of template DNA (diluted ligation product or diluted preamplification product). The selective EcoRI primer was labeled at the 5′ end with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6 FAM). All of the AFLP primer sequences are listed in Table 2, and the following selective primer combinations were used in this study: EcoRI-TG-MseI-TG, EcoRI-TG-MseI-CA, EcoRI-GT-MseI-GT, EcoRI-CA-MseI-GT, and EcoRI-CA-MseI-GA. The preamplification reaction conditions were 20 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The selective amplification conditions were 10 cycles consisting of 94°C for 60 s, 65°C for 60 s, decreasing 1°C every cycle, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by 23 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. All amplification reactions were performed in a Perkin Elmer model 480 thermal cycler.

AFLP fragment detection and analysis.

The selective amplification products were diluted fivefold in distilled H2O, and 1 μl of PCR product was transferred to a new tube, dried, and resuspended in 1 μl of formamide, 0.3 μl of internal size standard (GeneScan 1000 ROX or GeneScan 500 TAMRA; Applied Biosystems), and 0.7 μl of blue dextran loading buffer (Applied Biosystems). The mixtures were heated to 94°C for 2 min and snap-cooled on ice. One microliter of each sample was electrophoresed by using either an ABI 377 automated sequencer with a Gene-Page Plus 5% (6 M) urea gel (Amresco) or an ABI 373XL automated sequencer with a 5% Long Ranger gel (FMC). All gels used 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The ABI 377 gels were electrophoresed for 4.5 h at 200 W with plates with a 36-cm well-to-read distance, and the ABI 373XL gels were electrophoresed for 11 h at 24 W with plates with a 24-cm well-to-read distance. Data collection, fragment sizing, and pattern analyses were done with GeneScan, version 3.1, analysis software (ABI).

Polymorphic loci were defined as bands of the same mobility present in some isolates and absent in others. The relative mobility of each fragment was accurately calculated by the inclusion of an internal size standard within each sample. Bands were first identified visually and subsequently confirmed with ABI GeneScan, version 3.1, software. For each polymorphic locus, there were two possible alleles which were scored as 1 when the amplified fragment was present and 0 when the fragment was absent. A polymorphic locus was included in the analysis only if it was present or absent in at least five of the isolates, was strongly amplified, and was greater than 40 bp and less than 500 bp in size. A total of 38 loci from five gels fit the above criteria.

Data analysis.

The index of association (IA) (4, 32) and tree length tests (2, 5) were used to distinguish between recombining and clonal modes of reproduction. The IA is a statistical test that measures the degree of nonrandom association between alleles at different loci (linkage disequilibrium) and was calculated by using the Multilocus, version 1.0b, software (1). The tree length test uses the permutation test in PAUP*, version 4.0b4a (D. L. Swofford, Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.), to calculate the length of phylogenetic trees by treating the isolates as taxa and the alleles at each locus as phylogenetic characters with two character states. Both analyses involved comparing the values for the observed data set with the values for 1,000 artificially recombining data sets. The artificially recombining data sets were constructed by randomly shuffling the alleles for each locus between members of the population while keeping the proportions of alleles at each locus constant. An inability to distinguish between the observed data set and the artificially recombined data sets would support the null hypothesis of sexual recombination, whereas a significant difference between the data sets would support clonality (5, 8).

The multilocus genotype results were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA) in an attempt to explain the variance among many variables (AFLP loci) in terms of a reduced number of uncorrelated factors, or principal components. PCA was conducted by using Minitab, release 12.1 (Minitab Inc., State College, Pa.). The PCA scores from those components explaining 95% of the variability were subsequently used in a canonical variate analysis (CVA). The goal of CVA was to analyze the relationship between the isolates and the eucalypt tree from which they were collected, to give a graphical representation of the spatial distribution of isolates between trees. CVA was calculated by using Genstat for Windows, 4th edition, software. The first two dimensions of the CVA scores were trapped since they contain the majority of information about the differences in trees. These were plotted against each other by using Minitab, release 12.1.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted by using Genstat for Windows software on the first 14 principal components. MANOVA was performed by using Genstat, 4th edition, software to statistically assess the differences in the spatial distribution of genotypes between trees. The null hypothesis was that there was no significant association between the isolates and the tree from which they were collected.

RESULTS

Sampling results from trees and air in Renmark.

C. neoformans var. gattii was cultured from 8 of 15 trees (53%) sampled in April 1999 with sterile swabs. From the 15 trees, 37 sites were sampled, 26 (70%) of which were positive for C. neoformans var. gattti. In July 1998, a total of 17 eucalypt trees were sampled and C. neoformans var. gattii was grown from 8 (47%) of the trees. From the 17 trees, a total of 55 sites were sampled, 17 (31%) of which were positive. Many of the positive sites sampled grew at least 20 colonies per plate, with some sites growing in excess of 200 colonies. The majority of positive samples came from tree hollows, and the yeast colonized a number of different hollows on some trees (Table 1). Four trees (13, 14, 19, and B) were colonized by both α and a strains. In trees 13 and 14, these occurred together in one hollow. None of the air samples were positive for C. neoformans.

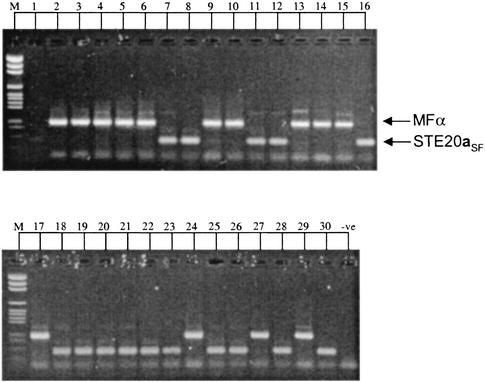

Coamplification with the MFα and STE20aSF primers.

The MFα and STE20aSF primers successfully amplified a 109-bp fragment and 219-bp fragment from all culture collection strains of C. neoformans var. gattii known to be of the α and a mating types, respectively (19). All of the C. neoformans var. gattii isolates obtained from Renmark were successfully amplified either by the MFα primers to give a 109-bp fragment or by the STE20aSF primers to give a 219-bp product. No isolates produced both the MATα- and MATa-specific PCR fragments. The amplification profiles are shown in Fig. 2, and the mating type assigned to each isolate is listed in Table 1.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic separation of DNA amplified by the MFαU, MFαL, STE20aSFU, and STE20aSFL primers. The marker (M) is a pGEM size standard (Promega), lanes 1 to 30 are isolates R1 to R30, respectively, and the final lane (−ve) is the negative (no DNA) control. Primer dimers can be seen below many of the amplified fragments.

AFLP analysis.

The five different AFLP primer combinations each generated between 4 and 13 polymorphic bands that were considered suitable for the analysis. It was noticed that 4 of the 38 loci chosen were in complete linkage disequilibrium with the mating type locus. Loci AD, AG, and AI had the (1) (band present) allele in a mating type strains only, and locus AK had the (1) allele in α strains only. These four loci were removed from the study.

In each AFLP amplification profile, isolates R8, R9, and R16 shared many large (>500 bp) AFLP fragments, in addition to sharing many common smaller bands with the other 27 isolates. Unfortunately, complete digestion had not been verified with lambda DNA in these particular isolates, and these were therefore removed from the AFLP analysis in case the variation seen in the selective amplification profiles was due to incomplete enzyme digestion. The multilocus genotypes for the remaining 27 isolates are shown in Table 3. No two isolates shared an identical multilocus genotype.

TABLE 3.

AFLP multilocus genotypes for C. neoformans var. gattii isolates from Renmarka

| Locus | Result for isolate:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 (A) | R2 (B) | R3 (C) | R4 (D) | R5 (E) | R6 (F) | R7 (G) | R10 (H) | R11 (I) | R12 (J) | R13 (K) | R14 (L) | R15 (M) | R17 (N) | R18 (O) | R19 (P) | R20 (Q) | R21 (R) | R22 (S) | R23 (T) | R24 (U) | R25 (V) | R26 (W) | R27 (X) | R28 (Y) | R29 (Z) | R30 (AA) | |

| A | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| E | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| G | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| H | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| J | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| K | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| M | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| R | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| U | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| V | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| W | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Y | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Z | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| AC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ADb | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AE | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| AF | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AGb | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AH | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| AIb | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AJ | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| AKb | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| AL | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The columns R1 to R30 are the 27 C. neoformans var. gattii isolates and the rows A to AL are the loci included in the analysis. After each isolate designation, the multilocus genotype is indicated in parentheses. Loci A to G were amplified by primers EcoRI-GT-MseI-GT, loci H to T were amplified by primers EcoRI-CA-MseI-GT, loci U to AB were amplified by primers EcoRI-CA-MseI-GA, loci AC to AH were amplified by primers EcoRI-TG-MseI-TG, and loci Al to AL were amplified by primers EcoRI-TG-MseI-CA. 1, amplified band present; O, amplified band absent.

Locus was removed from the study when it was realized that it segregated the isolates according to their mating types.

The reproducibility of the AFLP technique was examined by repeatedly analyzing identical isolates. DNA was extracted four times from three different C. neoformans var. gattii strains, and each DNA sample was analyzed by AFLP. The independent DNA preparations yielded almost identical AFLP patterns for each strain (data not shown). Slight variations were observed in some faint bands, perhaps due to template variation. As no faint polymorphic bands were included in the analysis, this was not expected to affect the analysis in any way.

Population genetic and phylogenetic analysis of multilocus genotype data.

The observed multilocus genotypes for the 27 C. neoformans var. gattii isolates from Renmark (Table 3) were artificially recombined 1,000 times, and the IAs and tree lengths were calculated for both the observed and artificially recombined data sets. Comparison of the IA values for the observed and recombined data sets showed the observed IA value (3.32) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than the recombined IA values (−0.2 to 0.3), causing the null hypothesis of random recombination in this population to be rejected.

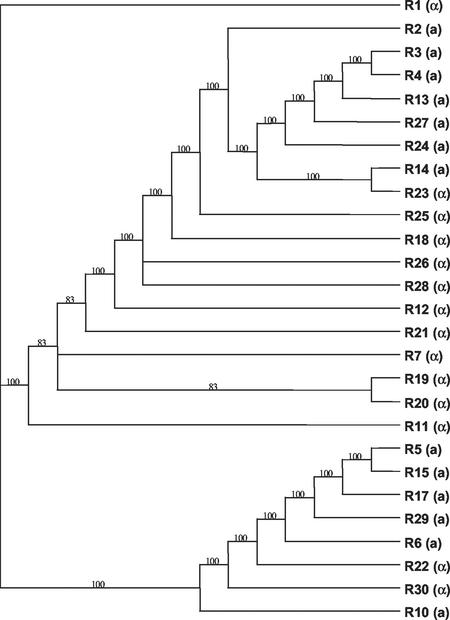

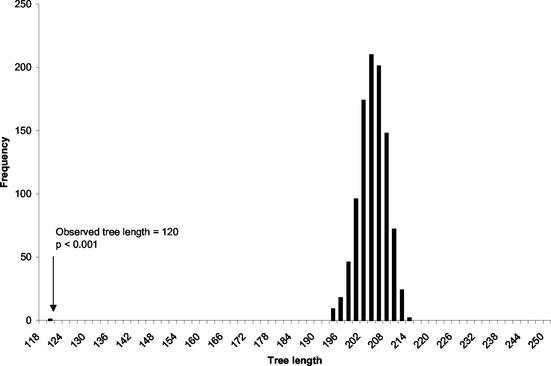

Phylogenetic analysis of the AFLP data found 18 most parsimonious trees for the multilocus data. The strict consensus tree was well resolved, and all the branches were supported by high (>80%) bootstrap values. The tree divided the isolates primarily according to their mating types (Fig. 3). Comparison of the observed tree length with the tree lengths of the 1,000 artificially recombined data sets found the observed tree length (120 steps) to be significantly shorter than the tree lengths for the recombined data sets (194 to 214 steps; P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). This result again caused the null hypothesis of free recombination to be rejected and strongly suggested that reproduction in the Renmark population is predominantly asexual.

FIG. 3.

Strict consensus of the 18 most parsimonious trees, calculated by using PAUP* (Sinauer Associates), determined from 34 AFLP loci. The numbers above the branches represent the percentage of the 18 most parsimonious trees that support this branch.

FIG. 4.

Histogram showing the distribution of tree lengths for 1,000 artificially recombined data sets and the observed tree length for the Renmark population based on 34 AFLP loci.

Finally, the IA and tree length tests were performed on 8 isolates of both the α and a mating types (R5, R6, R10, R15, R17, R22, R29, and R30) that formed a distinct cluster on the phylogenetic tree that was separate from the other 19 isolates (Fig. 3). Removal of the other 19 isolates reduced the number of informative sites to 15. The observed IA and tree lengths were still significantly different (P < 0.004 and P < 0.01, respectively) from those of the 1,000 artificially recombined values (data not shown).

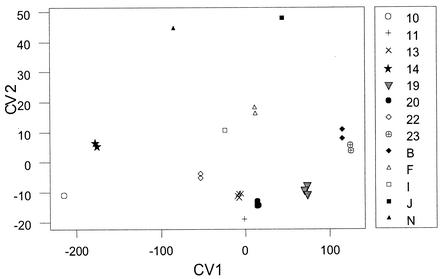

PCA and CVA.

PCA reduced the number of variables from 34 AFLP markers to 14 principal components that explained 95% of the variation in the data set, and these values were subsequently used in the CVA. The CVA plot of the first two canonical variates revealed good separation of the genotypes of isolates from each of the 13 Eucalyptus trees surveyed (Fig. 5). A clear distinction was apparent between the C. neoformans var. gattii isolates depending on the Eucalyptus tree from which they had been collected. The CVA did not reveal any correlation between the genetic relationship of the isolates and the geographical location of the Eucalyptus tree. For example, trees 13 and 14 are situated within 20 m of each other, yet the genotypes of the isolates from these two trees appear distinctly different on the CVA graph. In contrast, the isolates from trees 13 and 20 are genetically more closely related, yet the distance between the trees is greater than 80 m (Fig. 1 and 5).

FIG. 5.

Plot of 27 C. neoformans var. gattii isolates for the first two CVA scores (CV1 and CV2). The key shows the trees from which the isolates were obtained.

MANOVA.

MANOVA revealed a significant difference between the genotypes of the isolates depending on which of the 13 eucalyptus trees they had been collected from (P < 0.00001).

DISCUSSION

The increasing importance of medical fungi, combined with improved molecular typing and analysis techniques, has greatly increased the level of research into the population genetics and epidemiology of these fungi. Population studies of pathogenic fungi to date have predominantly used clinical isolates (5, 8, 14, 15, 17), but unlike most fungal pathogens, C. neoformans var. gattii can be easily isolated from its environmental niche in Australia. This provided a unique opportunity to analyze the population structure of a medically important fungus in its natural environment. We previously surveyed for the presence of the two mating types in C. neoformans var. gattii isolates from different geographic regions of Australia and found that in the majority of populations one of the two mating types predominated. In most cases, the α type dominated, but in a single population from Balranald, New South Wales, isolates were predominantly of the a type (19). Given the nearly 1:1 ratio of the two mating types in Renmark, it seemed reasonable to expect that recombination had been occurring in this population and was maintaining the two mating types at approximately equal levels. Founder effects would explain the dominance of one or other mating type in other populations, which would be locked into clonal propagation through the absence of the appropriate mating partner.

Clonality and limited dispersal in the C. neoformans var. gattii population from Renmark.

Despite the two mating types occurring together in Renmark, all analyses of this population found it to have a clonal structure. Tests for clonality rely on finding an association between alleles at loci that are not physically linked. We chose AFLP to provide loci for this analysis, as this technique is highly discriminatory and each AFLP band is independent from all others. As incomplete digestion of DNA prior to amplification would cause AFLP bands to cosegregate and cause the population to appear clonal, digestions were rigorously checked, and any profiles that looked to be derived from partially digested DNA were excluded. The inclusion of bands from five different AFLP profiles was also done to help reduce artifactual associations.

In addition to the IA and tree length tests showing an association between alleles, CVA and MANOVA of the AFLP data found genotypes of isolates collected from different trees to be significantly different (Fig. 5). The exchange of genetic information between individual isolates from different Eucalyptus trees therefore appears to be negligible. Interestingly, CVA also found isolates present on the same tree were genetically more similar to one another, irrespective of their mating type. This was surprising, given that all of the analyses used in this study segregated the population into two lineages predominantly based on mating type. This may reflect an initial colonization by a few genetically similar α and a genotypes, followed by some recombination within the confines of individual trees to produce very closely related offspring. It is therefore possible that the geographic area chosen for this analysis, although confined to a radius of less than 2 km, was not restricted enough. Choosing a population to test for recombination relies on maximizing the chance for recombination between members of the population. We chose isolates from a limited geographic region but a number of different trees, as it was thought that intensive sampling of one or a few trees might result in the resampling of members from single clonal lineages. In addition, we hypothesized that if sex was occurring, basidiospores would be produced and would be dispersed between trees, allowing recombination between isolates from different trees. It is possible that our sampling strategy was too broad and that the Renmark population consists of a number of subpopulations associated with single trees, within which recombination occurs. However, a preliminary study of isolates collected beneath a single colonized tree in Balranald, New South Wales, found extremely limited diversity and a strongly clonal structure (unpublished data). This population consisted of both mating types, although there was a predominance of the a type (19). Obtaining isolates from beneath the tree suggested that the fungus was dispersing into the environment, although it is also possible that it was propagating on the fallen tree debris. This result suggests that, even in very geographically confined sites, asexual propagation is strongly favored over recombination.

It should also be noted that despite repeated attempts by our laboratory and others, with a range of different techniques, no successful matings have been performed between any of the Renmark isolates, including those found together in one tree hollow (18; R. L. Tsarke, D. A. Carter, W. Meyer, and K. J. Kwon Chung, Abstr. 5th Int. Conf. Cryptococcus Cryptococcosis, abstr. P01, 2002). In addition, electrophoretic karyotype analysis of the isolates from Renmark revealed considerable heterogeneity in chromosome number and genome size between isolates, identifying six major genetic profiles (I to VI) consisting of between 9 and 13 chromosomes (18). Meiosis is thought to select against chromosome length polymorphisms, so any major differences in chromosome number or length would be expected to impede sexual recombination between strains (51). This is further evidence of mating incompatibility that could give rise to the clonal population structure.

Almost all other medically important fungi with an environmental component to their life cycles have been found to have a predominantly recombining population structure (5, 7, 9, 20). The one exception to this has been C. neoformans var. neoformans, where mixed results have been seen. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE), electrophoretic karyotyping, and DNA sequence analysis all demonstrated few genotypes over a wide geographic region (3, 15, 42); the explanation for this was extensive clonal propagation of C. neoformans var. neoformans on pigeon guano and the worldwide expansion of the pigeon population. When a recombination analysis, which used both tree length and IA tests, was done with the MLEE data, including both A and D serotypes, clonality was concluded (15). However, when Taylor et al. used some of the MLEE data and performed the recombination analyses on members of a single serotype, the significance of the IA test was reduced (P < 0.05) and that of the tree length test was completely lost (39). Taylor et al. concluded that genetic differentiation had occurred between the two serotypes and that there was the possibility of recombination within each serotype. In addition, parsimony analysis of the URA5 gene sequence returned 1,276 most parsimonious trees, which should not be the case in a clonal organism (15). Gene genealogical analysis and the presence of AαDa and AaDα hybrids have suggested that hybridization events can also occasionally occur between the C. neoformans serotypes and varieties (48-50). The combination of asexual propagation, sexual recombination, and interserotype and/or intervariety hybridization could contribute to the survival and success of C. neoformans var. neoformans, which is ubiquitous and cosmopolitan. Interestingly, there is also evidence of hybridization between C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (49), as seen by the presence of some C. neoformans var. neoformans alleles in two serotype B strains.

What is the role of the eucalypt in the life cycle of C. neoformans var. gattii?

A paradox in the epidemiology and population genetic structure of C. neoformans var. gattii throughout Australia has been that, despite vast geographic distances and a proposed evolutionary relationship between the fungus and native Australian Eucalyptus species, the genetic diversity of C. neoformans var. gattii throughout the Australian continent is low. We hypothesized that the specific relationship between C. neoformans var. gattii and the eucalypt host would mean that the yeast undergoes sexual recombination to complete its life cycle on the tree, resulting in the production and widespread dissemination of sexual basidiospores. Our results, however, indicate the opposite: that clonal propagation predominates and that dispersal from colonized trees is negligible. This may indicate that the relationship between the two organisms is less ecologically relevant than previously thought.

Other studies also indicate that the eucalypt tree may not represent the total environmental niche for C. neoformans var. gattii (22, 36). Papua New Guinea has a relatively high incidence of cryptococcosis due to C. neoformans var. gattii, but the environmental source of these infections has not been confirmed in any of the imported or endemic Eucalyptus species, nor does the distribution of infections mirror the distribution of the eucalypt trees (26). An alternative environmental source has likewise been proposed in Malaysia, where clinical cases are not associated with regions in which potential host eucalypts have been planted (21). In addition, numerous recent studies have shown that while the majority of environmental isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii have come from certain species of Eucalyptus, it is not an exclusive association (12, 35; T. J. Pfeiffer and D. H. Ellis, Abstr. Int. Meet. Aust. N. Zeal. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. P5.6, 1996). Other trees from which the fungus has been isolated include the smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata) and turpentine gum (Syncarpia glomulifera) in Australia (19, 43); the pink shower tree (Cassia grandis), fig tree (Ficus microcarpa), and pottery tree (Moquilea tomentosa) in Brazil (27, 28); and almond trees (Terminalia catappa) in Colombia (6). It appears that decaying wood is favorable for C. neoformans var. gattii growth, but it may simply be serving as a substrate for clonal propagation and the primary ecological niche may lie elsewhere.

Sex is important in fungi for reassorting genomes, increasing genetic diversity, and producing resistant propagules that can colonize new environmental niches. Although the division Deuteromycotina consists of fungal species that seem to have lost their ability to undergo sexual reproduction, population genetic analysis has revealed that genetic exchange can occur cryptically in at least some of these species (5, 16). In addition, only a very small level of genetic exchange is enough to disrupt clonality and return a result of recombination (5). It was therefore surprising that, in a fungus with a known sexual cycle and in a region in which both mating types occur, recombination and dispersal seem to be lacking. Even if recombination does occur in individual tree hollows, this may only result in extensive inbreeding without any dissemination. It will be of interest to see if clinical populations return the same result, as presumably the infection is initiated by inhalation of a dispersed propagule and the basidiospore has been found to be significantly more infectious than a desiccated yeast cell, at least in an animal model (38).

We conclude that clonal propagation and limited dispersal characterize this population from Renmark, South Australia. Although our results are confined to a single population, there is little to suggest that other Australian populations associated with Eucalyptus trees will be different; indeed, their skewed mating type ratios suggest that sex may not even be possible. In addition, the low level of genetic diversity found in C. neoformans var. gattii throughout Australia argues for widespread clonality. We propose that C. neoformans var. gattii has spread to the eucalypt host from another environmental niche and that the conditions present in decaying eucalyptus wood have provided a favorable substrate for extensive asexual growth, which has occurred relatively recently. We are now directing our analysis to clinical isolates both from around Australia, in particular from the Northern Territory where the normal host eucalypts do not occur, and from Papua New Guinea, which has an unknown environmental reservoir. Sexual reproduction, resulting in infectious basidiospores, may explain the relatively high incidence of cryptococcosis due to C. neoformans var. gattii in these regions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant 970648), the Ramacioitti Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Research Institute, under the International Scholars Program (grant no. 55000640). C.H. thanks the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Sydney for financial support through the Alexander Hugh Thurburn Scholarship.

We thank Justin O'Grady for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agapow, P.-M., and A. Burt. 2001. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes 1:101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archie, J. W. 1989. A randomization test for phylogenetic information in systematic data. Syst. Zool. 38:239-252. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt, M. E., M. A. Pfaller, R. A. Hajjeh, E. A. Gravis, J. Rees, E. D. Spitzer, R. W. Pinner, L. W. Mayer, and Cryptococcal Disease Active Surveillance Group. 1996. Molecular subtypes and antifungal susceptibilities of serial Cryptococcus neoformans isolates in human immunodeficiency virus-associated cryptococcosis. J. Infect. Dis. 174:812-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, A. H. D., M. W. Feldman, and E. Nevo. 1980. Multilocus structure of natural populations of Hordeum spontaneum. Genetics 96:523-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt, A., D. A. Carter, G. L. Koenig, T. J. White, and J. W. Taylor. 1996. Molecular markers reveal cryptic sex in the human pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:770-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callejas, A., N. Ordonez, M. C. Rodriguez, and E. Castaneda. 1998. First isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii serotype C, from the environment. Med. Mycol. 36:341-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter, D., R. Reynolds, N. Fildes, and T. J. White. 1996. Future applications of PCR to conservation biology. In T. B. Smith and R. K. Wayne (ed.), Molecular genetic approaches in conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 8.Carter, D. A., A. Burt, J. W. Taylor, G. L. Koenig, and T. J. White. 1996. Clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum from Indianapolis, Indiana, have a recombining population structure. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2577-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter, D. A., J. W. Taylor, B. Dechairo, A. Burt, G. L. Koenig, and T. J. White. 2001. Amplified single-nucleotide polymorphisms and a (GA)n microsatellite marker reveal genetic differentiation between populations of Histoplasma capsulatum from the Americas. Fungal Genet. Biol. 34:37-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis, D. H., and T. J. Pfeiffer. 1992. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis, D. H., and T. J. Pfeiffer. 1990. Ecology, life cycle and infectious propagule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Lancet 336:923-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis, D. H., and T. J. Pfeiffer. 1990. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1642-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher, M. C., G. L. Koenig, T. J. White, and J. W. Taylor. 2000. Pathogenic clones versus environmentally driven population increase: analysis of an epidemic of the human fungal pathogen Coccidioides immitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forche, A., G. Schönian, Y. Gräser, R. Vilagalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 1999. Genetic structure of typical and atypical populations of Candida albicans from Africa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 28:107-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzot, S. P., J. S. Hamdan, B. P. Currie, and A. Casadevall. 1997. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans in Brazil and the United States: evidence of both local genetic differences and a global clonal population structure. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2243-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geiser, D. M., J. I. Pitt, and J. W. Taylor. 1998. Cryptic speciation and recombination in the aflatoxin-producing fungus Aspergillus flavus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:388-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gräser, Y., M. Volovsek, J. Arrington, G. Schönian, W. Presber, T. G. Mitchell, and R. Vilgalys. 1996. Molecular markers reveal that population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:12473-12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halliday, C. L. 2000. A molecular study of mating type and recombination in Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. Ph. D. thesis. University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

- 19.Halliday, C. L., T. Bui, M. Krockenberger, R. Malik, D. H. Ellis, and D. A. Carter. 1999. Presence of α and a mating types in environmental and clinical collections of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii strains from Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2920-2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasuga, T., J. W. Taylor, and T. J. White. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of varieties and geographical groups of the human pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum Darling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:653-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keah, K. C., S. Parameswari, and Y. M. Cheong. 1994. Serotypes of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans in Malaysia. Trop. Med. 11:205-207. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidd, S. 1999. An epidemiological study of Cryptococcus neoformans using a computer-based pattern of analysis system. Honours thesis. University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

- 23.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1976. Morphogenesis of Filobasidiella neoformans, the sexual state of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycologia 68:821-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1978. Distribution of α and a mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans among natural and clinical isolates. Am. J. Epidemiol. 108:337-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. W. Fell. 1984. Filobasidiella Kwon-Chung, p. 472-482. In N. J. W. K. v. Rij (ed.), The yeasts: a taxonomic study. Elsevier Science B. V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 26.Laurenson, I. F., D. G. Lalloo, S. Naraqi, R. A. Seaton, A. J. Trevett, A. Matuka, and I. H. Kevau. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans in Papua New Guinea: a common pathogen but an elusive source. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 35:437-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazéra, M. S., M. A. S. Cavalcanti, L. Trilles, M. M. Nishikawa, and B. Wanke. 1998. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii-evidence for a natural habitat related to decaying wood in a pottery tree hollow. Med. Mycol. 36:119-122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazéra, M. S., F. D. A. Pires, L. Camillo-Coura, M. M. Nishikawa, C. C. F. Bezerra, L. Trilles, and B. Wanke. 1996. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans in decaying wood forming hollows in living trees. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 34:127-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lengeler, K. B., P. Wang, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. Identification of the MATa mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans reveals a serotype A MATa strain thought to be extinct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14455-14460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levitz, S. M. 1991. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:1163-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madrenys, N., C. De Vroey, C. Raes Wuytack, and J. M. Torres-Rodriguez. 1993. Identification of the perfect state of Cryptococcus neoformans from 195 clinical isolates including 84 from AIDS patients. Mycopathologia 123:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maynard-Smith, J., N. H. Smith, M. O'Rourke, and B. G. Spratt. 1993. How clonal are bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4384-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald, B. A., and J. M. McDermott. 1993. Population genetics of plant pathogenic fungi. Electrophoretic markers give unprecedented precision analyses of genetic structure of populations. Bioscience 43:311-319. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milgroom, M. G. 1996. Recombination and the multilocus structure of fungal populations. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34:457-477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Pfeiffer, T. J., and D. H. Ellis. 1992. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from Eucalyptus tereticornis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 30:407-408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorrell, T. C., S. C. A. Chen, P. Ruma, W. Meyer, T. J. Pfeiffer, D. H. Ellis, and A. G. Brownlee. 1996. Concordance of clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii by random amplification of polymorphic DNA analysis and PCR fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1253-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staib, F. 1962. Cryptococcus neoformans and Guizotia abyssinica. Z. Hyg. 148:466-475.

- 38.Sukroongreung, S., K. Kitiniyom, C. Nilakul, and S. Tantimavanich. 1998. Pathogenicity of basidiospores of Filobasidiella neoformans var. neoformans. Med. Mycol. 36:419-424. [PubMed]

- 39.Taylor, J. W., D. A. Geiser, A. Burt, and V. Koufopanou. 1999. The evolutionary biology and population genetics underlying fungal strain typing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:126-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Taylor, J. W., D. J. Jacobson, and M. C. Fisher. 1999. The evolution of asexual fungi: reproduction, speciation and classification. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37:197-246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Tibayrenc, M., F. Kjellberg, and F. J. Ayala. 1991. The clonal theory of parasitic protozoa. A taxonomic proposal applicable to other clonal organisms. Bioscience 41:767-774.

- 42.Tibayrenc, M., F. Kjellberg, and F. J. Ayala. 1990. A clonal theory of parasitic protozoa: The population structures of Entamoeba, Giardia, Leishmania, Naegleria, Plasmodium, Trichomonas and Trypanosoma and their medical and taxanomical consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2414-2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Vilcins, I., M. Krockenberger, H. Agus, and D. A. Carter. 2002. Environmental sampling for Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from the Blue Mountains National Park, Sydney, Australia. Med. Mycol. 40:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Viviani, M. A., M. C. Esposto, M. Cogliati, M. T. Montagna, and B. L. Wickes. 2001. Isolation of a Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A MATa strain from the Italian environment. Med. Mycol. 39:383-386. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. van de Lee, M. Hornes, A. Frijters, J. Pot, J. Peleman, M. Kuiper, and M. Zabeau. 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4407-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Wen, H., R. Caldarelli-Stefano, A. M. Tortorano, P. Ferrante, and M. A. Viviani. 1996. A simplified method to extract high-quality DNA from Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Mycol. Med. 6:136-138.

- 47.Wickes, B. L., M. E. Mayorga, U. Edman, and J. C. Edman. 1996. Dimorphism and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans: association with the α-mating type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7327-7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Xu, J., G. Luo, R. Vilgalys, M. E. Brandt, and T. G. Mitchell. 2002. Multiple origins of hybrid strains of Cryptococcus neoformans with serotype AD. Microbiology 148:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Xu, J. P., R. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 2000. Multiple gene genealogies reveal recent dispersion and hybridisation in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Ecol. 9:1471-1481. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Yan, Z., X. Li, and J. Xu. 2002. Geographic distribution of mating type alleles of Cryptococcus neoformans in four areas of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:965-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Zeigler, R. S. 1998. Recombination in Magnaporthe grisea. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36:249-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]