Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate how important treatment for emotional distress is to primary care patients in general and to primary care patients with depression, and to evaluate the types of mental health interventions they desire.

DESIGN

Patient surveys.

SETTING

Five private primary care practices.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Patients’ desire for treatment of emotional distress and for specific types of mental health interventions were measured, as well as patients’ ratings of the impact of emotional distress, the frequency of depressive symptoms, and mental health functioning. Of the 403 patients, 33% felt that it was “somewhat important” and 30% thought it was “extremely important” that their physician tries to help them with their emotional distress. Patient desire for this help was significantly related to a diagnosis of depression ( p < .001), perceptions about the impact of emotional distress ( p < .001), and mental health functioning (p < .001). Among patients with presumptive diagnoses of major and minor depression, 84% and 79%, respectively, felt that it was at least somewhat important that they receive this help from their physician. Sixty-one percent of all primary care patients surveyed and 89% of depressed patients desired counseling; 23% of all patients and 33% of depressed patients wanted a medication; and 11% of all patients and 5% of depressed patients desired a referral to a mental health specialist.

CONCLUSIONS

A majority of these primary care patients and almost all of the depressed patients felt that it was at least somewhat important to receive help from their physician for emotional distress. The desire for this help seems to be related to the severity of the mental health problem. Most of the patients wanted counseling, but relatively few desired a referral to a mental health specialist.

Keywords: patient expectations, emotional distress, patient treatment desires, primary care mental health problems

Depression is one of the most common and important conditions found in the primary care setting.–4 Unfortunately, primary care physicians fail to recognize depression in at least half of their patients, and the treatment they provide is frequently less than optimal.–9 A majority of primary care physicians cite patient resistance to diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders as an important obstacle to providing this care.10,11 The purpose of this study was to evaluate this common physician perception by investigating how important treatment for mental health problems is perceived to be by primary care patients in general and by primary care patients with presumptive diagnoses of major or minor depression in particular. We also evaluated the types of mental health treatments these patients desired. Finally, we sought to learn more about the characteristics of patients who desire mental health treatment by evaluating the factors (e.g., severity of depressive symptoms, severity of medical problems, functional status, age, gender, and race) that might contribute to patients’ perceptions about the importance of treatment for their emotional distress.

METHODS

The study, conducted in 1995 in five adult primary care practices in the Philadelphia area, included 403 patients. All patients seen in those practices during enrollment days who were between the ages of 15 and 75 were consecutively considered for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included dementia and other factors (e.g., language, incapacitating illness, and poor vision) that would make it difficult for a patient to read and understand the self-administered questionnaires. Only 9.4% of patients who were eligible refused to participate. All questionnaires were completed in the primary care physician’s waiting room before the patient’s visit.

We evaluated the patient’s desire for treatment of emotional distress by asking, “How important is it to you that your doctor tries to help you with your emotional distress?” Possible responses included (1) “not at all important,” (2) “somewhat important,” and (3) “extremely important.” Patients were also asked, “During the past week, how much effect has emotional distress had on the way you have been feeling and functioning?” Responses ranged from 1 = “no effect at all” to 3 = “a great deal of effect.” The nine core symptoms of depression were evaluated by a self-administered version of the Primary Care Evaluation of Medical Disorders Procedure (PRIME-MD),1 with a 5-point Likert response scale for each symptom ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “constantly” (all day, every day). Patients met criteria for a presumptive diagnosis of major depression if they indicated they had five depressive symptoms “frequently” (nearly every day) or “constantly” during the past 2 weeks and at least one of these symptoms was depressed mood (“feeling down, depressed or hopeless”) or anhedonia (“little interest or pleasure in doing things”). The criteria for a presumptive diagnosis of minor depression were that the patient acknowledge from two to four depressive symptoms occurring “frequently” or “constantly,” at least one of which was depressed mood or anhedonia.

In a subset of 273 consecutively enrolled patients we included the Medical Outcome Study Short Form General Health Survey (MOS SF-20).12 The MOS SF-20 measures functional status across six dimensions—bodily pain, physical functioning, role functioning, social functioning, mental health functioning, and health perception (all scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning). In this subset we also asked physicians to rate their patients’ overall physical health from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent.

A second subset of 130 consecutive patients were also asked to indicate the ways they felt their doctor might help them with their emotional distress during the visit. Possible responses included (1) Listen to me describe the emotional distress in my life; (2) Help me understand the nature of this distress better; (3) Offer me advice on how to deal with this distress; (4) Reassure me that this distress will improve; (5) Discuss what effects, if any, this distress might have on my physical health; (6) Prescribe a medication to help me relax or feel happier; and (7) Refer me to a mental health specialist. For the purpose of this analysis, we considered the first five interventions under the general heading of counseling.

RESULTS

Of the 403 study patients, 65% were female and 51% were white. The mean age of the sample was 45.7 years (SD ± 16.2 years). Mental health symptoms were common in this population, with 42% indicating that emotional distress was having “some effect” on the way they had been feeling and functioning, and another 18% indicating that it had “a great deal of effect.” Thirty-two patients (8%) met the criteria for a presumptive diagnosis of major depression, while another 36 (9%) met the criteria for a presumptive diagnosis of minor depression. When patients were asked how important it was that their primary care physician try to help them with their emotional distress, 37% considered it to be “not at all important,” while 33% felt it was “somewhat important,” and 30% thought it was “extremely important.”

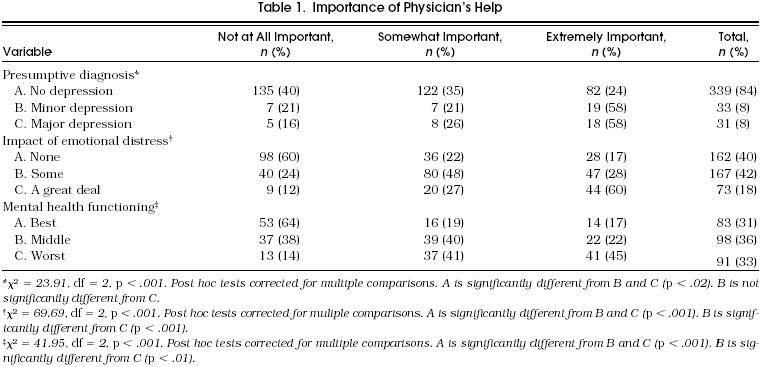

There was a significant main effect (χ 2 = 23.91, df = 2, p < .001 by Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance) of depression diagnosis on patients’ desire for help with their emotional distress (see Table 1). Almost all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of major depression (84%) and minor depression (79%) were at least somewhat interested in receiving help for their emotional distress. Post hoc paired comparisons among the three groups revealed that patients with major depression and minor depression were significantly more likely to desire treatment for emotional distress than patients with no depression (p < .02 using the Mann-Whitney U Test with Bonferroni’s correction for type 1 errors). Patients with major depression were not different in this regard from patients with minor depression.

Table 1.

Importance of Physician’s Help

Two other global measures of mental health functioning were used to evaluate the relation between the severity of mental health problems and how important patients felt it was for their physicians to help them with their emotional distress (Table 1). One measure of mental health functioning was based on patients’ responses to the question on the effect of emotional distress on how well they were feeling and functioning. The other measure came from the mental health subscale on the MOS SF-20 with patient scores divided into tertiles. In both cases, as mental health functioning got progressively worse, the importance patients attached to treatment of emotional distress increased (main effects were significant at p < .001, and all paired comparisons were significant at p < .01 using the Mann-Whitney U Test with Bonferroni’s correction for type 1 errors).

To evaluate the influence of other variables (age, gender, race, functional status, and severity of medical illness) on patients’ desires for treatment of emotional distress, we ran a multiple regression analysis in which we controlled for severity of mental illness by forcing in the three measures of severity of mental illness (depressive symptoms, impact of emotional distress on how well the patient was feeling and functioning, and the score on the MOS SF-20 mental functioning subscale) in step 1. These three variables collectively explained 25% of the variance in the patients’ rating of the importance of obtaining treatment for their emotional distress. In step 2, the remaining independent variables included patient’s age, gender, race, the six subscales of the MOS SF-20, and the physician’s rating of the severity of medical illness. Of these variables only social functioning entered the equation, explaining only another 1% of the variance in patients’ desires for treatment of emotional distress. It thus appears that after severity of mental health illness is accounted for, the patient’s demographic characteristics, functional status, and severity of medical illness contributed very little to their desire for mental health treatment.

A subset of the sample of primary care patients (n = 130) was given a list of potential mental health interventions that could be provided by their primary care physician. For the purpose of this analysis, the interventions that involved listening, increasing patient understanding, offering advice, providing reassurance, and discussing the impact of distress were placed together under the general heading of counseling. Overall, 62% of these patients desired some form of counseling from their primary care physician for their emotional distress; 23% wanted their physician to prescribe a medication to help them relax or feel happier, and 11% desired a referral to a mental health specialist. Patients who felt it was “extremely important” for their doctor to help them with their emotional distress were more likely to request counseling than those who felt it was “somewhat important” or “not at all important” (97% vs 78% vs 15%, p < .001). The same types of differences also existed when comparing the “extremely important,” “somewhat important,” and “not at all important” groups in terms of their desire for medications (47%, 22%, and 2%, p < .001) and referral (22%, 13%, and 0%, p < .001).

In the subset of the sample asked to indicate a preference for potential interventions, 9 patients (7%) had a presumptive diagnosis of major depression and 12 patients (9%) had a presumptive diagnosis of minor depression. Taken together 71% of patients with these mood disorders desired counseling, 33% wanted a medication, and 5% wanted a referral.

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that depressed patients are not reluctant to express a desire for help with their emotional distress when they are specifically asked about it. Approximately 84% of patients with a presumptive diagnosis of major depression and 79% of patients with a presumptive diagnosis of minor depression were at least somewhat interested in help from their primary care physicians for these emotional problems. In fact, a majority of all primary care patients felt that it was either “extremely important” (30%) or “somewhat important” (33%) for their physician to help them with their emotional distress.

Patients’ desire for help for their emotional distress was related to the severity of their depressive symptoms and their mental health functioning. Yet the percentage of primary care patients who were at least somewhat interested in help for their emotional distress (63%) appears to be greater than the known prevalence of diagnosable mental health disorders in primary care.1 This phenomenon has been recognized by other investigators, such as David Goldberg, MD,13 who argues that many emotionally distressed patients who do not meet the formal criteria for a mental health disorder will still benefit from their primary care physician’s attention to their distress.

Our data indicate that most, but certainly not all, of those patients who were likely to benefit from treatment of emotional distress felt that it was at least somewhat important to receive help from their physician for their distress. Sixteen percent of the patients with a presumptive diagnosis of major depression, 12% of patients who indicated that emotional distress was having a great deal of effect on the way they were feeling and functioning, and 14% of patients in the worst tertile of mental health functioning did not feel it was important for their physician to try to help them with their emotional distress. Some of these patients may have already been receiving help from a mental health specialist. Others may have been concerned about the stigma associated with mental health disorders. Some patients may have believed that their emotional problems would get better on their own or that they were capable of coping with them without their physician’s help.

Nonetheless, our data suggest that it may be useful for primary care physicians to ask routinely about the impact of emotional distress on how their patients have been feeling and functioning and to inquire about their interest in receiving help for emotional distress. More than half of the patients in our sample responded positively to these questions, including almost all of the patients with major or minor depression. These questions, therefore, may be useful in screening for depression. They might also be used to identify the patients with subthreshold levels of mental health disorders who warrant treatment, as patients who recognize that their emotional distress is affecting how they are feeling and functioning, and who desire help for it, may be the ones who are most likely to benefit from some form of treatment. Other studies have also demonstrated the importance of eliciting patient expectations for care. In the primary care setting, unmet patient expectations have been shown to be related to decreased patient satisfaction.14,15 In the psychiatric setting physicians’ efforts to elicit patients’ requests and negotiate treatment plans led to improved health outcomes, adherence, and satisfaction.16

Patients who desire help for their emotional distress almost always want an opportunity to discuss their emotional problems with their primary care physicians. They are much less likely to desire medication or a referral. We noted the same distribution of intervention desires among patients with major and minor depression. Most of these patients wanted counseling, about one third desired a medication, and 5% wanted a referral. These data are consistent with those of other investigators who found that a large proportion of patients suffering from psychiatric symptoms would actually prefer to be treated in the primary care setting.10,17 It should be recognized, however, that firm conclusions about the specific intervention desires of patients with a depressive disorder should not be drawn until these findings are corroborated in a larger sample and at multiple sites.

Our study supports the belief that primary care physicians should become actively involved in the identification and management of mental health disorders, which have been shown clearly to occur commonly in primary care settings.1,6,7,18 We found that even more primary care patients will indicate, if asked, that they have emotional distress that affects the way they are feeling and functioning, and for which they appear to desire treatment from their physician. The vast majority of these emotionally distressed patients do not want to be referred to a mental health specialist. Rather, most patients prefer to discuss their emotional distress and related problems with their primary care physician, and some may also want a prescription for a psychotropic medication.

It is admittedly challenging for primary care physicians to provide efficient and effective counseling. This may be an impossible task. However, strategies for brief counseling interventions in primary care have been developed,–21 and several studies have suggested that these kinds of strategies can be effectively employed in the primary care setting.–23

REFERENCES

- 1.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267:1478–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamerow DB, Pincus HA, MacDonald DI. Alcohol abuse, other drug abuse, and mental disorders in medical practice: prevalence, costs, recognition, and treatment. JAMA. 1986;255:2054–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulberg HC, Burns BJ. Mental disorders in primary care: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and treatment research directions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler LG, Cleary PD, Burke JD. Psychiatric disorders in primary care: results of a follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:583–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ormel J, Koeter MWJ, van den Brink W, van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borus JF, Howes MJ, Devins NP, Rosenberg R, Livingston WW. Primary health care providers’ recognition and diagnosis of mental disorders in their patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:317–21. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Korff M, Myers L. The primary care physician and psychiatric services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9:235–40. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(87)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orleans CT, George LK, Houpt JL, Brodie HKH. How primary care physicians treat psychiatric disorders: a national survey of family practitioners. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:52–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–32. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg D. A classification of psychological distress for use in primary care settings. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:189–93. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90166-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brody DS, Miller SM, Lerman CE, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Blum MJ. The relationship between patients’ satisfaction with their physicians and perceptions about interventions they desired and received. Med Care. 1989;27:1027–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kravitz RL, Cope DW, Bhrany V, Leake B. Internal medicine patients’ expectations for care during office visits. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:75–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenthal S, Emery R, Lazare A, et al. Adherence and the negotiated approach to patienthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:393. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780040035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford DE, Kamerow DB, Thompson JW. Who talks to physicians about mental health and substance abuse problems? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:363–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02595795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett JE, Barrett JA, Oxman TE, Gerber PD. The prevalance of psychiatric disorders in a primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1100–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brody DS, Thompson TL, Larson DB, Ford DE, Katon WJ, Magruder KM. Strategies for counseling depressed patients by primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:569–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02599285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catalan J, Gath DH, Anastasiades P, Bond SAK, Day A, Hall L. Evaluation of a brief psychological treatment for emotional disorders in primary care. Psychol Med. 1991;21:1013–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klerman GL, Budman S, Berwick D, et al. Efficacy of a brief psychosocial intervention for symptoms of stress and distress among patients in primary care. Med Care. 1987;25:1078–88. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker R, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brody DS, Lerman CE, Wolfson HG, Caputo GC. Improvement in physicians’ counseling of patients with mental health problems. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:993–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]