Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We studied whether a simple educational intervention would increase patient completion of advance directives and discussions on end-of-life issues.

DESIGN

Randomized, controlled trial.

SETTING

Outpatient clinic of a teaching hospital.

SUBJECTS

One hundred eighty-seven outpatients of a primary care internal medicine clinic.

INTERVENTION

Study subjects attended a 1-hour interactive seminar and received an informational pamphlet and advance directive forms. Control subjects received by mail the pamphlet and forms only.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Completion of the advance directive was the main measurement. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics of either group. Follow-up at 1 month revealed advance directive completion in 38% of study versus 24% of control subjects (p = .04), and discussions on advance planning in 73% of study versus 57% of control subjects (p = .02). Patients most likely to complete the documents were white, married, or attendees at the educational seminar.

CONCLUSIONS

Interactive group seminars for medical outpatients increased discussions and use of written advance directives.

Keywords: advance directives, living wills

A consensus statement by the nation’s leading bioethicists concluded that advance directives, both living wills and durable powers of attorney, may help resolve legally and ethically troubling cases.1 The Patient Self Determination Act requires that hospitals and other health care agencies provide education to staff and community on issues concerning patients’ rights to formulate advance directives (OBRA-90 P.L. 101-508, § 4206). Despite public awareness of these rights and an increase of general discussions of end-of-life issues with proxies, the actual use of formalized documents remains poor.2 However, patients with formal, written care planning have been shown to have significantly more frequent and detailed discussions with their physicians and proxies than patients with less formalized arrangements.2

Encouraging the formation of written documents for medical outpatients during times of relative wellness seems logical. However, the optimal format for educating patients and encouraging completion of these documents has yet to be determined as even time-intensive, physician-directed interventions have had varied results.3,4 In a randomized controlled trial, we compared the use of an educational seminar with mailed, written information to determine whether either would increase the use of advance directives by medical outpatients.

METHODS

Subjects were recruited in the spring of 1992 from the General Internal Medicine Clinic at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, a 750-bed military teaching hospital with an outpatient case mix similar to that of other teaching hospitals.5 All patients receiving care in the clinic over a 4-week period were asked to complete a questionnaire. The questionnaire collected basic demographic information and asked questions related to current advance-directive planning such as whether previous discussions with health care providers had occurred or whether advance directives had been completed. As well, patients were asked whether or not they would like more information regarding advance directives, specifically living wills. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete the questionnaire owing to language or cognitive barriers or unwillingness to participate in the study.

Study subjects included only those that requested more information and did not already have a written living will. Eligible subjects were contacted by telephone and asked whether they were still interested in receiving information. If so, they were randomized into a study group (educational seminar) or control group (mailed written information only). Our institutional review board believed that we needed to provide the control group with at least the written information and later offer them the opportunity (after study completion) to attend the seminar in light of the federal Patient Self Determination Act. The 60-minute educational seminar was administered in a standardized format to 20 patients during each session by one of the investigators (FJL or CL) and included the following: (1) a didactic presentation (10 minutes) that discussed and defined advance directives, durable power of attorney for health care, and organ donation; (2) a 15-minute videotape provided by the Society for the Right to Die detailing formulation of advance directives6; (3) an interactive discussion (30 minutes) in which patients could discuss issues and have questions answered; and (4) distribution and review of a recommended advance directive form (10 minutes).

Each page of the advance directive was reviewed, and the participants were told to use the information as they wished. The research assistant (CL) was trained by the one of the investigators (FJL) in two sessions to ensure consistency in the presentations. The advance-directive form was chosen for its user-friendly composition. The form, which is widely available and used in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, included portions for a living will, durable power of attorney, and organ donation. Our main outcome of interest was whether the living will portion of the form was completed. The control group received by mail the advance directive form and an information pamphlet7 that was distributed to all patients. Patients randomized to the seminar group who failed to attend the seminar received a mailing similar to that received by the control group.

One month after the interventions, a follow-up questionnaire was mailed to patients in both groups. Nonresponders were sent a second questionnaire. Anyone not completing a questionnaire was given one telephone call. All subjects contacted confirmed that the document had been completed. The follow-up questionnaire inquired about the occurrence of (1) discussions of advance directives with family members, friends, or physicians; (2) the establishment of written advance directives (living wills, durable powers of attorney, and organ donation cards); and (3) attitudes regarding acceptability of the intervention.

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS/PC, Chicago, Ill.). Student’s t test was used to compare means, and χ2 analysis was used to test associations among categorical data. Intention-to-treat analysis was performed. In the stepwise, forward, logistic regression analysis, the dependent variable was completion of the advance directive at 1-month follow-up.

RESULTS

Five-hundred questionnaires were distributed to consecutive patients in the outpatient medical clinic during a 4-week period. We excluded 148 (31%) of the patients who had previously completed an advance directive and 14 whose questionnaires were incomplete. Of the original 500, 333 (69%) had no advance directive, and of these 233 requested further information. We excluded 46 of these 233 patients prior to randomization—30 who subsequently refused to participate when contacted by telephone, 14 who lived outside our geographic area, and 2 who had completed advance directives prior to randomization. In all, 187 outpatients with no advance directive who were interested in receiving more information were randomized to either the study group (seminar plus information) or control group (mailed information only).

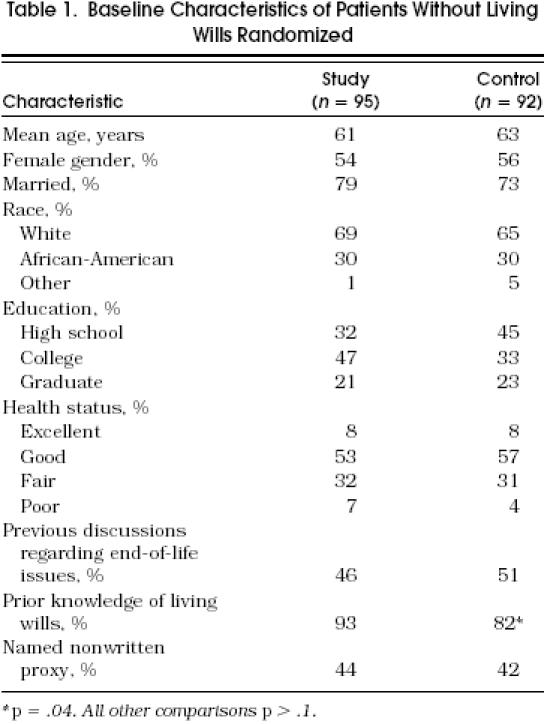

As shown in Table 1, the 95 study group and 92 control group participants were similar except that study patients were slightly less likely to have had prior knowledge of advance directives (82% vs 93%, p = .04). Notably, prior information about advance directives typically had been provided by the media (70%) rather than the patient’s physician (2%). Likewise, nearly half of all the patients had already had discussions regarding end-of-life issues, but these discussions were usually with family members (60%) rather than physicians (2%). Less than half of all patients had named a nonwritten health care proxy, and none had a written, durable power of attorney. Organ donation cards had been completed by 9% of study and 5% of control patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Without Living Wills Randomized

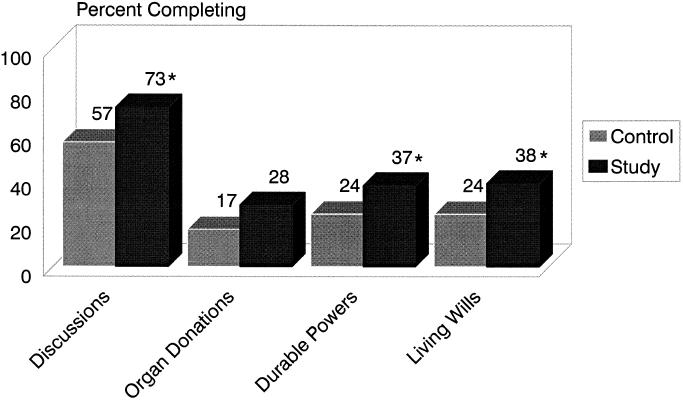

Complete follow-up was obtained in 91% of study and 90% of control participants at 1 month. Sixty-five (68%) of the 95 patients randomized to the seminar group actually attended the seminar. Demographic data for those attending and for those not attending were similar. Discussions regarding end-of-life issues and completion of organ donation cards, durable powers of attorney, and living wills increased in the study group as compared with the control group (Fig. 1) Of the 65 patients actually attending the seminar, nearly half (48%) completed the living will. Of those completing the living will, seminar participants were more likely than control patients to give a copy to their health care proxy (73% vs 40%, p = .01) and place the document in their outpatient medical record (45% vs 30%, p = .17), although they were no more likely to tell their primary physician that they had completed the document (18% vs 15%, p = .76). Interestingly, one quarter of patients in the control group who completed the document did so with the help of a lawyer as opposed to only 3% in the seminar group.

Figure 1.

Outcomes of the intervention on the initiation of discussions and the completion of living wills and directives for organ donation and durable powers of attorney. *p < .05.

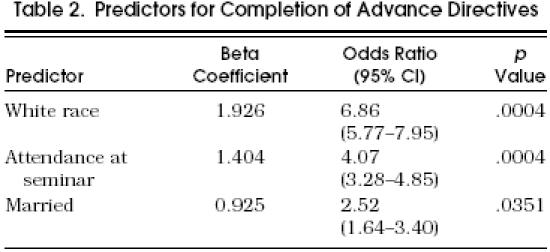

At 3 months after the seminar, we contacted a 30% random sample of those stating they had completed the advance directive on the follow-up questionnaire. All patients confirmed that they had indeed completed the document. Table 2 depicts the three predictors of advance-directive completion determined by our logistic model. Perceived health status, age, and gender were not predictors.

TAble 2.

The majority of patients in both groups (92% seminar vs 77% control, p = .02) believed that the information they received about advance directives was beneficial to them. Less than 5% of patients in either group stated that the information they received worried them, and the majority in both groups (94% seminar vs 82% control) believed that they received adequate information on the topic.

DISCUSSION

Advance directives allow patients to document preferences regarding health care in the event of impaired decision-making capacity in the future. These documents may include not only the living will but also directives on the designation of health care proxies as well as wishes regarding organ donation. Despite much emphasis from the media and physician groups on increasing the completion of these forms, few people appear to have completed directives.8 As well, the optimal method to increase discussions with patients on end-of-life issues and completing written directives remains unclear.9

In a randomized, controlled trial, we demonstrated that mailed information alone can increase completion of advance living wills and directives for durable power of attorney for health care and organ donation. Further, a simple, educational seminar can double completion rates. Both mailed information and seminar information were considered beneficial to the majority of patients, and few patients found the information bothersome. Several previous studies have suggested a modest effect of patient education on increasing the completion of advance directives. Hare and Nelson increased completion from 0% to 12% through distributed information and physician discussions,3 and Rubin et al. demonstrated that mailed information can lead to more written durable powers of attorney for health care in elderly patients.10 These studies support wider use of educational strategies to increase completion of these documents.

The process of completing directives is more complex than just filling out a form; it includes proper framing of the issues and their integration into the longitudinal doctor-patient relationship.3 Interventions like ours, which combine educational information, advance-directive forms, and group discussions, may provide a forum that stimulates discussion and thus enhances completion. These discussion groups may have allowed patients the opportunity to ask more questions, receive more answers, and share experiences that otherwise would not occur. Such a model can be adapted to many settings, including the outpatient clinic, preoperative clinic, or even the in-hospital setting. This intervention may be less time intensive and produce more written documents than one-on-one physician-patient counseling.11

We found that white, married patients were more likely to complete advance directives. More than half of our participants had more than a high school education. This characteristic of our population is likely to have increased baseline rates and completion rates because it appears that cultural, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds affect completion rates.12,13 Perhaps different types of educational initiatives will need to be developed for different patient subgroups. However, group forums like ours are efficient means to disseminate information, answer questions, and produce written directives.

Completion of an advance directive is not enough to ensure that the patient’s wishes are honored. Despite our intervention, less than 20% of patients told their primary physician that they had completed an advance directive, and less than half of the patients completing the document placed it in their medical record. This low percentage may reflect in part the fact that follow-up was conducted 1 month after the intervention, and it is possible that other discussions and documentation occurred later. We did find, however, that 73% of patients in the seminar group provided a written directive to their health care proxy. Morrison et al. showed that only 26% of 114 geriatric patients with known advance directives had their directives recognized during their hospitalization, and these seldom were noted by either the admitting clerk or physician.14 Fortunately, when the advance directive was recognized, it influenced treatment decisions in 86% of the cases. More emphasis should be placed on encouraging patients to inform their physicians about written directives. Likewise, physicians should routinely ask and document whether such directives have been established.

Our educational intervention is likely to be useful in other outpatient settings as our population has demographic characteristics similar to those of other general medicine clinics.5 However, the patients entered into the study most likely were more motivated than the average patient as all of the randomized patients had requested more information on advance directives. Although completion rates were determined only 1 month after the intervention, we believe that completion of the advance directive was most likely to occur in a relatively short interval.

The Patient Self Determination Act requires that health care facilities provide written information to individuals on the right to formulate advance directives. Our study showed that group seminars can provide information that is acceptable to patients and can lead to increased completion of written advance directives.

References

- 1.Annas GJ, Arnold B, Aroskar M, et al. Bioethicists’ statement on the U.S. supreme court’s Cruzan decision. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:686–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009063231020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emmanuel EJ, Weinberg DS, Gonin R, Hummel LR, Emmanuel LL. How well is the patient self-determination act working? An early assessment. Am J Med. 1993;95:619–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90358-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hare J, Nelson C. Will outpatients complete living wills? A comparison of two interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:41–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02599390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno J, Fleishman J, Brock DW, et al. The use of formal prior directives among patients with HIV-related diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:490–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02600877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JE, Pinholt EM, Jenkins TR, Carpenter JL. Content of ambulatory internal medicine practice in an academic Army medical center and an Army community hospital. Mil Med. 1988;153:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Right to Die . New York, NY: Society for the Right to Die; 1988. The Choice is Yours [videotape] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choice in dying . South Deerfield, Mass: Channing L. Bete Co.; 1991. In: About Advance Medical Directives. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox DM, Sachs GA. Advance directives and the patient self-determination act. Clin Geriatr Med. 1994;10:431–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmanuel L. Advance directives: what have we learned so far? J Clin Ethics. 1993;4:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin SM, Strull WM, Fialkow MF, Weiss SJ, Lo B. Increasing the completion of the durable power of attorney for health care. A randomized, controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;271:209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs G, Stocking C, Miles S. Empowerment of the older patient? A randomized, controlled trial to increase discussion and use of advance directives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:269–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DM, Sachs GA. Advance directives and the patient self-determination act. Clin Ethics. 1994;10:431–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stelter KL, Elliot BA, Bruno CA. Living will completion in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:954–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison RS, Olson E, Mertz KR, Meier DE. The inaccessibility of advance directives on transfer from ambulatory to acute care settings. JAMA. 1995;274:478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]