Procedures are an integral part of medical practice. Most patients occasionally require a medical procedure during their regular care. Many patients expect their generalist physician, whether general internist, family physician, or pediatrician, to perform the most common procedures—especially those that are done in an office setting. Patients appreciate continuity and many may resist referral to another physician for reasons of cost and having to encounter an unfamiliar provider. Many physicians enjoy “using their hands” to perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Larimore and Sapolsky found that, at least for obstetric procedures, physicians who performed deliveries, compared with those who did not, showed, “increased financial and psychological satisfaction for the same hours worked and increased satisfaction with medicine.”1 Finally, procedures have usually resulted in higher physician compensation for a given period of time than cognitive care activities for a similar period of time. Typically a 5:1 payment ratio of procedural:cognitive activities per hour is seen by primary care physicians. Thus, until recently, patient expectation, physician interest, and economic reward all served as incentives for generalist physicians to perform procedures.

Many students and residents have exhibited marked interest in learning procedures.2,3 One study suggests that residency programs emphasizing procedural training have been more sought after by resident applicants than those not prioritizing procedures.3 Many primary care residents prefer to have these procedures taught by their own generalist faculty, rather than subspecialists. In addition, recent decisions by the American Board of Internal Medicine mandate certification by residency programs of core procedural competence of their graduating residents.4

The broadened presence of managed care plans has added yet another incentive for performance of procedures—the inclusion of many procedures in the list of services considered to be “primary care.” Often there is an economic disincentive for primary care physicians to send their patients elsewhere to obtain these services. Plans may capitate the primary care physician for all items (CPT codes) included under primary care, and the physician may be financially responsible if the patient must be sent elsewhere for these services. This new aspect of procedural medicine has increased the importance of adequate training in a basic set of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for primary care trainees.

It is essential that primary care physicians perform only procedures that they are capable of performing competently, with outcomes that are comparable to those achieved by their subspecialty colleagues. It is true that the literature supports highly complex procedures such as carotid endarterectomy and coronary artery bypass grafting being done only by highly subspecialized physicians.5–7 Several studies, however,have demonstrated that primary care physicians are able to master complex procedures such as colposcopy,8 cesarean section,9 and ultrasound,10 with results that are indistinguishable from those of more narrowly trained specialists.

Ferris and Miller, in their 1993 article, found that colposcopy performed by trained family physicians was equal in quality outcome to that done by gynecologic specialists.8 Deutchman and his colleagues have demonstrated similar findings on cesarean sections by family physicians9 and obstetric ultrasound by family physicians.10 Rodney's studies on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy have shown comparable safety and accuracy of these procedures when done by generalists compared with subspecialists.11,12 In summary, there is no evidence that for procedures which are less than highly complex and done reasonably often, primary care physicians provide procedural care that is of lower quality or results in more adverse outcomes than that of specialists.

WHICH SKILLS SHOULD BE TAUGHT

Given that performing procedures is essential for primary care physicians, the next logical concern is which procedures should be included in training. This question can be approached in several ways.

The first approach would be through expert consensus about which procedures should be taught in a discipline's training programs. This effort would, in effect, define the center portion of the procedural scope of practice for that discipline. Wigton has twice published the suggestion that programs in internal medicine need to decide which procedures their residents will master and need to ensure that residents receive training and develop competency in these procedures.4,13 A group decision of this nature by the internal medicine residency directors would certainly represent development of an “expert consensus.”

An alternative approach would be the creation of a process by which one could determine which procedures should be taught. The American Academy of Family Physicians recently convened the Task Force on Procedures, which developed the following recommendation: “Family practice residencies in the United States should teach those procedures that are taught in most [the majority of] family practice residencies, and those that are performed by most [the majority of] family physicians. . .”14 This approach creates a process through which one could survey residency programs and practicing physicians, allowing development of a list of procedures to be taught, based on surveys of residency programs and practicing physicians.

A third approach to this question would be individualized to each trainee, according to the intended location and the type of practice that a resident plans to seek, and based on the teaching capabilities of the training program. Smith and Klinkman recently observed that the choice of specific procedures for a physician in training might be based on the individual needs of the practice, most commonly seen diagnoses, current screening procedures, and economic issues.15 It is clear that exposure to procedural instruction increased the likelihood of performing the procedure in practice after training is completed,16 that younger physicians tend to do more procedures than their older colleagues in the same specialty,17 and that rural physicians do a wider variety of complex procedures than urban physicians.18

Each of the three approaches has inherent advantages and disadvantages. Although development of expert consensus is clearly feasible, it may be arbitrary and subjective. Process-driven models may be attractive intellectually, but may also be unwieldy and expensive to administer. Individualized approaches may be satisfying to trainees, but may require a degree of effort not available in many programs and may lose applicability if the resident's preferred practice site changes.

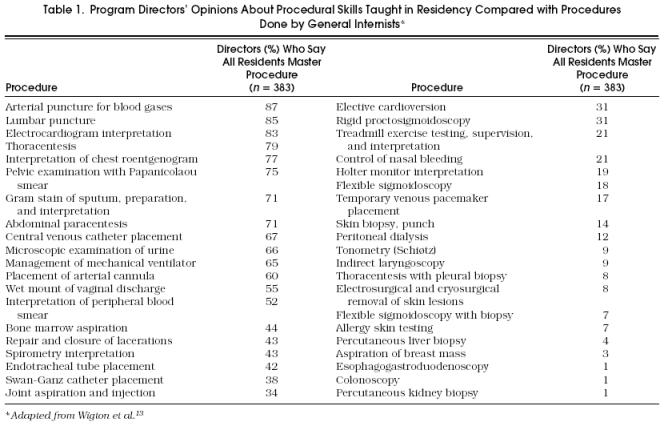

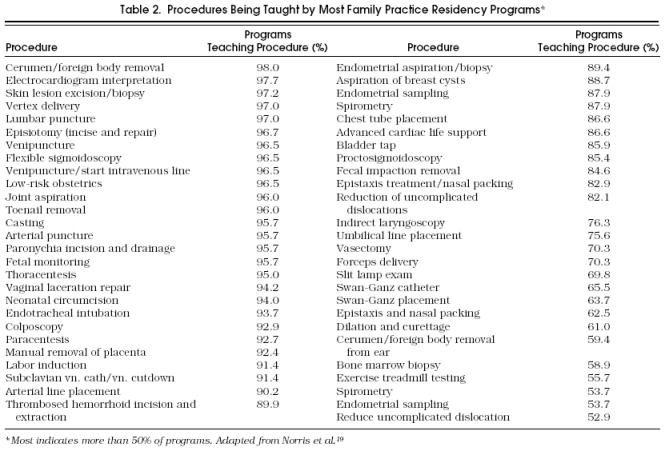

It is worthwhile to review available data regarding procedures that are being taught in primary care residencies. Table 1 presents Wigton's 1989 findings regarding procedures mastered by internal medicine residents, based on a survey of their residency directors.13 Table 2 illustrates the results of a 1994 survey of family practice residency program directors reported by Norris and his colleagues.19 Specifically, they listed procedures taught by the majority of family practice residencies. While there are no current data comparing procedural training in internal medicine residency programs, family medicine residencies, and pediatric residencies, the data presented represent the most comprehensive survey information available in the literature. It is interesting to note that electrocardiogram interpretation, joint aspiration and injection, lumbar puncture, arterial puncture, and thoracentesis rank high on the lists of procedures taught by both internal medicine and family medicine residency programs.

Table 1.

Program Directors’ Opinions About Procedural Skills Taught in Residency Compared with Procedures Done by General Internists*

Table 2.

Procedures Being Taught by Most Family Practice Residency Programs*

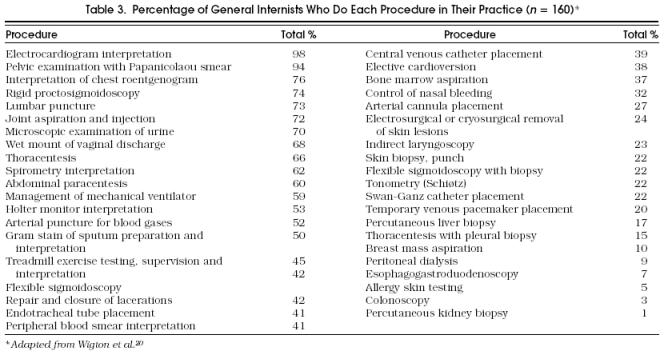

It is also worthwhile to review the procedures currently being performed by practicing generalists. In 1989 Wigton surveyed a sample of general internists and reported on the percentage of general internists performing various procedures in their practices.20 Table 3 presents Wigton's findings. Similarly, as shown in Table 4, in 1996 Norris and colleagues reported survey results of procedures being done by the majority of practicing family physicians.19 Although this information is not strictly comparable because Wigton reports on all procedures and Norris reports only on those done by more than 50% of practicing physicians, the data are useful in understanding the scope of procedures done by practicing primary care physicians.

Table 3.

Percentage of General Internists Who Do Each Procedure in Their Practice (n = 160)*

Table 4.

Procedures Being Performed by Most Family Practice Physicians*

HOW PROCEDURAL SKILLS SHOULD BE TAUGHT

Procedural skills are taught using a variety of educational methods. The traditional approach in medical education has been a lecture format. As purely descriptive lectures do not work well in describing an “action-oriented” task, these talks are frequently augmented with visual aids in the form of photographs, slides, films, and videotapes. These aids assist the learner in recognizing normal and abnormal findings and in understanding the actual performance of the procedure.

Perhaps the most common form of teaching procedural skills in medical school and residency settings has been the traditional demonstration, followed by supervised performance, and then by the newly trained learner undertaking the teaching role (“see one, do one, teach one”). It is no surprise that much of this training is provided by senior housestaff for their junior peers as well as for medical students. A minority of office-level procedures are taught by faculty in medical training settings.21 The challenge for the practicing physician is to locate similar opportunities in the practicing medical community, in order to learn to perform new and emerging procedures. It is the unusual community that can provide training to the practicing physician. The typical community situation offers ample potential preceptors. Unfortunately, these physicians are often unwilling to provide training, under the guise of “quality-of-care concerns,” but perhaps in reality based on concerns about competition and financial issues. The rural community often differs by offering a more supportive political atmosphere, but frequently no one is available with the procedural skills to be the instructor (of course, exceptions to these generalizations occur). Practicing physicians interested in developing new procedural skills must often look to their state and national specialty organizations for educational assistance.

The method used by the American Academy of Family Physicians and American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy to train family physicians in flexible sigmoidoscopy represents an excellent model of cooperation. The two organizations collaboratively prepared a comprehensive syllabus that covered equipment, its maintenance, pathology (with slides provided), and indications for procedure, with a written test to measure competency. The two organizations recruited a national list of qualified preceptors from both groups who directly supervised a set number of procedures with the students. If the student achieved sufficient mastery, a certification was supplied at the conclusion of the program. To the authors’ knowledge, no such similar program has been developed since the end of this effort. This program demonstrated that qualified generalists or subspecialists qualified by training or experience can serve as competent preceptors. Since that time, the difficulty has been in recruitment of preceptors, particularly among the subspecialty community, and their reluctance to serve as teachers. This scarcity has led to increasing reliance on generalists to provide procedural training for other generalists. Perhaps the expanding development of integrated multispecialty health systems with appropriate proportions of generalist and subspecialty providers will make this task of recruiting teachers easier as risk-sharing and capitated payment mechanisms become more the norm.

The “see one, do one, teach one” method may threaten patient safety if inadequately supervised, and the approach has been enhanced by using models or “mock” procedures.22 Another emerging approach to procedural training is the use of simulations, often utilizing computer technology.23 Simulations are widely used in aviation and other fields in which safety considerations place limits on the training environment, and they hold much promise in medicine.

Once a learner has progressed to the level of readiness to perform a procedure on a patient, the teacher assumes the role of preceptor. It is important to differentiate preceptors for procedural training from proctors. Preceptors are teachers who are providing close supervision to the learner during the performance of a procedure and are responsible for the safety of the patient in these situ-ations. Alternatively, proctor is usually the term applied to an individual who watches a trained physician perform a procedure, in order to check or certify the physician's competence for privileges or credentials. In this setting, the physician performing the procedure, not the proctor, is legally responsible for the safety of the patient. Who is responsible for the patient and the patient's safety is a major consideration in procedural training of physicians. There are differences in the procedural training of students, residents, and practicing physicians, and the question of responsibility for the patient is a major factor among these differences.

BARRIERS TO TEACHING PROCEDURAL SKILLS

Many of the barriers to teaching procedural skills relate to the nature of the teaching program, logistical constraints, and “turf ” issues or ownership of procedures in the practicing community.

The main barrier to procedural training in the majority of educational programs is the lack of faculty who are competent in specific procedural skills and readily available to provide training to residents and students.24 Programs interested in expanding procedural training often must obtain training for their faculty members themselves before offering it to their trainees. The procedural curriculum offered at the annual national meeting of the American Academy of Family Physicians is an excellent resource. Not only are typical primary care procedures offered at this meeting, such as workshops in wound closure, excision-biopsy, plastic surgery, casting-splinting, and endometrial biopsy, but also training in ultrasound, upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, and colposcopy is provided. A number of private and public organizations not associated with medical training institutions also offer procedural training, such as the Institute for Procedural Training in Midland, Michigan, Seminars & Symposiums of New York, New York, and Sharp Memorial Hospital of San Diego, California, among others. State specialty societies sometimes include procedural training as part of their annual meetings, as well as review courses offered by local medical schools and their departments.

Additional barriers for many training programs are space and access to equipment. Procedures often require a designated location, with more physical space than a standard examination room, which is not available in many residencies. Furthermore, expensive equipment is required to teach and perform many procedures, especially endoscopic procedures. Moreover, access to the equipment may be limited by maintenance costs and availability of support personnel. Sometimes funding for necessary equipment is unavailable, or in some cases, the funding is controlled by specialists who may be economically threatened by training generalists in the procedure in question.

The financial issues should be evaluated before an extensive program of procedural training is undertaken. Because of demands for faculty training, space allocation and development, and equipment acquisition, procedural training has high “up-front” costs. If the volume of patients requiring the procedure is adequate, reimbursement for procedures often quickly offsets the initial investment.

Access to adequate numbers of patients is often a problem, particularly for joint aspiration and injection and other procedures required by the American Board of Internal Medicine.4 Often strategies must be developed to allow residents and students access to patients in teaching settings outside the normal residency clinics. For example, the authors are aware of programs that increase their colposcopy training volume by linkages with Planned Parenthood and their vasectomy volume through relationships with the local health department's contraception clinic.

Another critical issue involves the influence within the community of practicing physicians who represent the specialty or subspecialty whose “turf” encompasses a specific procedure.25 This impact may be experienced by the training program as a problem in obtaining funds for procedural equipment from a hospital's capital equipment committee, or problems finding community-based specialists or subspecialists to teach a procedure. Such controversies may persuade trainees that obtaining training in a given procedure is unwarranted, because they might be unable to obtain privileges in the area when they enter practice.

TESTING FOR COMPETENCY

Primarily because of concern for patient safety, but also because of issues of liability for faculty and graduates, as well as credibility for training programs, it is essential to develop methods of ensuring that newly trained physicians are competent in procedures before privileges are granted.4 The traditional and most widely used community approach has been to assign a proctor who observes the physician performing the procedure and renders an opinion regarding the competence of the physician to be granted privileges for the procedure. This approach has been criticized as too subjective, leading to an alternative method of certification based on completion of a specified number of procedures in training. For several procedures, experimental studies or, more commonly, a consensus process have determined the minimum number of times a trainee must perform a specific procedure to gain competence and to qualify for privileges.13,26 This approach has been criticized by many because of its conflict with traditional hospital guidelines for granting privileges, its frequent reliance on consensus rather than experimentation to determine an adequate number of procedures to obtain privileges, and its tendency to place primary care physicians with a broad scope of practice at a disadvantage while creating advantages for subspecialists with a narrow practice scope.27

An alternative method of ascertaining procedural competency is objective testing. The American Academy of Family Physicians has undertaken a pilot program of competency testing for its members who participate in continuing medical education procedural skills training. This testing has been in three parts with a written test focusing on cognitive knowledge of the procedure (especially indications and contraindications), a slide test focusing on ability to visually recognize normal and abnormal findings, and a skills test utilizing models to test the learner's actual capability to perform a procedure. If the learner passes all of these tests, then a “Certificate of Readiness for Precepting” is issued. The learner is then encouraged to undertake precepted procedures, under the direction of a physician experienced in the procedure in question. It is hoped that this approach will provide more objectivity to the determination of competency. However, this approach does not solve the problems of availability and willingness of other community physicians to provide the precepting necessary for final achievement of certified competence.

Most questions regarding competency have, to date, focused on the newly trained physician and concerned decisions about granting initial privileges. More discussion will unquestionably arise in the area of how practicing physicians should maintain and document procedural competency.

INSTITUTING A MONITORING SYSTEM

The initial challenge for primary care residency programs is to address the aforementioned barriers, but the next task is to implement a system to track procedures performed under supervision by trainees. Training programs require this information not only to ensure that each trainee obtains adequate training and supervision for the procedure but also for credential verification when former trainees seek clinical privileges.

Smaller programs may be able to use a simple manual system of record keeping, particularly if they are based within a single facility or institution. Many family medicine programs fall into this category. For larger, multi-institutional programs that include many university-based internal medicine residencies, such record keeping can entail substantial organization. Four years ago a tracking system was established in the University of Washington Internal Medicine Residency Training Program. A set of committees initially identified 15 procedures that were to be “credentialled” for residents within the program, the number of procedures required to be competent, the expected schedule for achieving competency, and which individuals were deemed qualified supervisors for each type of procedure. These committees also assembled instructional materials for each procedure that described techniques of performance, indications, contraindications, and complications. These materials were put in large reference manuals placed throughout the system of hospitals and clinics. Each resident is issued a chart to record each supervised procedure on which the supervisor must sign. Copies of these charts are submitted to the residency program on a regular basis. The program director is then able to determine which residents are not progressing on schedule in procedural training and can take appropriate action. A side benefit of this system is that it establishes a mechanism for deciding who should perform a given procedure when several trainees express interest.

CONCLUSIONS

Procedures are an important component of the practice of medicine. Students and residents must be trained to perform procedures safely and well. Simultaneously, we must seek consensus on what procedures should be taught, and we must develop better, safer techniques to teach them. Finally, we must develop objective measures of initial and continuing competency for those who perform procedures. We must try to overcome the “turf” battles in this area and focus on what is best for patients, students, and residents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Larimore WL, Sapolsky BS. Maternity care in family medicine: economics and malpractice. J Fam Pract. 1995;40(2):153–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb JM, Rye B, Fox L, Smith SD, Cash J. State of dermatology training: the residents’ perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2):1067–71. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper MB, Pope JB, Goel R. Procedural training in family practice residencies: current status and impact on resident recruitment. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(2):189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wigton RS. Training internists in procedural skills. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(2):1091–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-12-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruby ST, Robinson D, Lynch JT, Mark H. Outcome analysis of carotid endarterectomy in Connecticut: the impact of volume. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10(2):22–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark RE. Outcomes as a function of annual coronary artery bypass graft volume. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:21–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00734-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal AH, Rummel L, Wu B. The utility of PRO data on surgical volume: the example of carotid endarterectomy. Qual Rev Bull. 1993 doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris DG, Miller MD. Culposcopic accuracy in a residency training program. J Fam Pract. 1993;36(2):515–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutchman M, Connor P, Gobbo R, Fitzsimmons R. Outcomes of caesarean sections performed by family physicians and the training they received. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(2):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodney WM, Deutchman ME, Hartman KJ, Hahn RG. Obstetric ultrasound by family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1992;34(2):186–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodney WM, Weber JR, Swedberg JA, et al. Esophogogastroduadenoscopy by family physicians phase 2: a national multisite study of 2500 procedures. Fam Pract Res J. 1993;13(2):120–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hocutt JE, Rodney WM, Zurad EG, et al. Esophogoduadenoscopy for the family physician. AFP. 1994;49(2):109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wigton RS, Blank LL, Nicolas JA, Tape TG. Procedural skills training in internal medicine residencies: a survey of program directors. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(2):932–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Family Physicians . Kansas City, MO: American Academy of Family Physicians; 1994. Minutes of the Task Force on Procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MD, Klinkman MS. The future of procedural training in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 1995;27(2):535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad JA, Pirie P, Sprafka JM. Relationship between flexible sigmoidoscopy training during residency and subsequent sigmoidoscopy performance in practice. Fam Med. 1994;26(2):250–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliason BC, Lofton SA, Monte DH. Influence of demographics and profitability on physician selection of family practice procedures. J Fam Pract. 1994;39(2):341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goeschel DP, Gilbert CS, Crabtree BF. Geographic variation in exercise testing by family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(2):132–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norris TE, Felmar E, Tolleson G. Which procedures should be currently taught in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 1997;29:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wigton RS, Nicolas JA, Blank LL. Procedural skills of the general internist: a survey of 2500 physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(2):1023–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-12-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elnicki DM, Shumway JM, Halbritter KA, Morris DK. Interpretive and procedural skills of the internal medicine clerkship. South Med J. 1996;89(2):603–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199606000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodney WM, Richards E, Ounanian LL, Morrison JD. Constraints on the performance of minor surgery by family physicians: study of a ‘mock’ skin biopsy procedure. Fam Pract. 1987;4(2):36–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/4.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinclair MJ, Peifer JW, Haleblian R, Luxenberg MN, Green K. Computer simulated eye surgery. A novel teaching method for residents and practitioners. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(2):517–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor PD, Deutchman ME, Hahn RG. Training in obstetric ultrasound in family medicine residencies: results of a nationwide survey and suggestions for a teaching strategy. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1994;7(2):124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brotzman GL, Mark DH, Wolkomir MS. Influences on teaching culposcopy and treatment modalities in family practice programs. Fam Med. 1995;27(2):310–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawes R, Lehman G, Hast J, et al. Training resident physicians in fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy: how many supervised examinations are required to achieve competence? Am J Med. 1986;80:465–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris TE, Susman JL. Beyond the battlefield: bringing science and rationality to competency assessment, privileging and credentialing. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52(2):785–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]