Many academic physicians in generalist divisions spend a large proportion of their time in clinical practice and teaching. A 1979 study by Friedman and coworkers reported that faculty in divisions of general internal medicine spent 48% of their time in clinical practice, 31% in teaching, 12% in administration, and 9% in research.1 Results were similar for academic pediatrics,2 and for emergency medicine3; current data on other disciplines are lacking. In many institutions, the growth of this group of faculty preceded the development of satisfactory academic policies regarding reappointment, promotion, tenure, and institutional commitment. In these institutions, the extent and quality of teaching plays little role in the decisions about promotion and tenure.4,5 As the number of full-time clinician-educators has grown,6 the need for improved policies has increased.6,12

In response to this growing need, an estimated 63% (N.M. Jensen and J. Stewart, manuscript submitted) to 83%13 of departments of medicine have established special promotion tracks for clinician-educators (current data are not available for other disciplines). Some of these tracks carry either prefixes or suffixes to distinguish them from the traditional tracks that have existed for medical researchers, and no two tracks are identical.6 Despite the existence of these tracks, many clinician-educators remained concerned about faculty rewards and advancement.14,15 Of eight valued reforms for medical education, “reward for teaching” received the strongest support in a 1989 survey of 1,369 American medical educators.15 Among medical school faculty and administrators responding to a 1992 survey, the most frequently mentioned problems concerned methods to evaluate and reward teaching.16

Among traditional rewards for medical faculty, promotion and tenure remain the most valued; most young faculty would like to attain the rank of full professor.11,17 Although it is important for medical schools to pay clinician-educators competitive incomes, higher salaries alone are not sufficient to attract and retain talented physicians.18 Promotion and tenure remain the utmost recognition of scholarship, even though many institutions are redefining their tenure privileges and have initiatives to reduce the number of tenured faculty.6,17,19 This scholarship, defined elsewhere,20 must satisfy two criteria: excellence (as judged by peers) and dissemination in the public domain.13 Excellence in patient care and teaching, including efficiency and availability, must be considered as part of this scholarship.

It is essential to establish and maintain stringent criteria for the selection, development, and promotion of clinician-educators.7 Although many schools have these policies, they lack standardization across departments and universities.16 There is a need not only for widely accepted criteria by which clinician-educators may be fairly evaluated, but also for a reconsideration of how scholarship is defined.20 Expectations must be clear concerning how faculty are to spend their time, what they are to achieve, how they will be judged, and during what time frame.16 It is for these reasons that the Society of General Internal Medicine created the following guidelines for the promotion of clinician-teachers.21 We anticipate these guidelines will be useful to all academic clinical departments (with some discipline-specific adaptation).

AIM AND INTENDED USE

By proposing these guidelines, we aim to assist academic clinical departments in the important task of selecting, supporting, and rewarding clinician-educators; and to enhance the contributions and impact of academic clinical departments whose future depends increasingly on excellence in teaching and clinical service.

We anticipate that these guidelines will be useful to promotions committees at medical schools that may wish to use these guidelines in formulating their own specific criteria that meet the unique needs and priorities of their own schools; to department chairs and deans of medical schools in evaluating and comparing faculty members; to division chiefs and mentors who advise junior faculty; and to junior faculty members who need to actively manage their career, structure and focus their efforts, and evaluate their own performance. Although these guidelines are developed by and for academic general internists, the recommendations may also be appropriate for clinicians in other disciplines involved in teaching and clinical work.

For the purposes of this article, clinician-educators are defined as faculty whose primary responsibilities are to teach and educate medical students, housestaff, postdoctoral fellows, and practicing physicians (including program development, implementation, and evaluation) while simultaneously maintaining a clinical practice that is a model for learners and often serves as the site for these teaching functions.

PRINCIPLES GUIDING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THIS STATEMENT

A department's reappointment and promotion criteria should embody what is expected of its faculty.12,16,22 The concepts of reappointment, promotion, scholarship, and expectations require further delineation. Reappointment is the regular recontracting (every 1 to 3 or more years) with an academic faculty member. Reappointment does not necessarily mean promotion, although many universities time these together. Although scholarship is important for reappointment, other issues must be considered more flexibly. For example, most new faculty require 5 years to launch a successful academic career, even with reasonable provision for protected time and participation in fellowships or faculty-development programs.22 New clinician-educators may be delayed in establishing a patient base, and practices that include students may be less efficient than nonteaching practices.23,24 This is a special concern for teaching in high-volume managed care settings.17,24,25 Thus, many junior faculty may need to be reappointed before they are ready to be considered for promotion.

Promotion, the advancement from lowest to highest academic rank for active faculty (e.g., from assistant to full professor), is the reward for growth and maturation. Faculty are promoted by both their department and their medical school because they have made scholarly contributions that are valued by their department, school, and discipline.18

A central expectation for promotion is “scholarship.”26 Scholarship for a clinician-educator is the act of seeking, weighing, formulating, reformulating, and communicating knowledge of clinical practice or teaching. Substantial scholarship should be a requirement for the promotion of clinician-educators. This scholarship should be sustained, capable of assessment by peers, and disseminated in the public domain. The definition of scholarship for a clinician-educator is critical; it must be expanded beyond the publication of original quantitative data to include scholarship in educational methods and teaching, scholarship in clinical practice application, and scholarship of integration.20 These forms of scholarship are briefly elaborated upon below. These areas should not be considered a loose collection of activities, but rather an organized involvement in medical education and clinical practice that advance one's professional career. Because a career is developmental (a work in progress), change in focus occurs over time; this should be expected and valued.12

Research is both a separate form of scholarship and an integral part of the scholarly areas mentioned above. Clinician-educators should be encouraged to engage in research, especially in evaluating programs and studying the patients they see. Obstacles in performing research (e.g., focus, time) can be overcome,27 but it is unreasonable to expect clinician-educators to devote equivalent amounts of time to research and continue to perform all activities equally well.22 Many will serve as collaborators, rather than principal investigators, on extramurally funded projects. Clinician-educators should contribute to institutional review boards, to the setting of research priorities, and to the interpretation of data on collaborative research.

Expectations and explicit criteria for promotion should be used to define faculty responsibilities, including clinical practice, teaching, and medical investigation. Faculty should have a clear understanding of these expectations and criteria to guide the distribution of their efforts and to develop their careers.12 The rate and probability of academic progression for clinician-educators should not be appreciably different from those for faculty who perform other, equally important activities such as research and administration. Clinician-educators must be eligible for equivalent institutional status, reward, and voting privileges. Access to tenure should be no different for clinician-educators than for faculty members who make contributions to the academic mission of the institution in other ways (although the relevance of tenure to primarily clinical faculty is debatable).

PROMOTION CRITERIA AND EVALUATION

Every school must decide how to weigh the various types of scholarship produced by its faculty. Although all areas of performance and scholarship may be critical for the contemporary medical school department, it is not reasonable to require that each faculty member excel equally in all to achieve rewards, institutional status, and promotion.

Previous work demonstrates a discrepancy between perceptions of faculty members and department chairpersons regarding academic promotion criteria.28 At the time of hiring, new faculty should be informed of their institution's expectations, resources, performance standards, and evaluation processes. Written job summaries, letters of understanding or clarification, and faculty manuals will facilitate the process and are encouraged (to the extent that they do not inhibit creativity). What is negotiable and nonnegotiable should be clear. A useful approach may be the creation of a professional development contract,12 or creativity contract.20 This contract includes a personal assessment of strengths, interest, and weaknesses; professional responsibility; opportunities for learning and development during the coming academic year; details about patient care, teaching, administration, and scholarly goals; the resources that each goal requires; personal growth or learning opportunities that may be needed; and the type and source of performance feedback that would be helpful. It is essential that individual performance always be judged in the context of the resources and time available.

Frequent evaluation with feedback is critical to the growth and development of a faculty member. Every junior faculty member should affiliate with a senior mentor, who serves to review the professional development contract or other goal-oriented documents several times throughout the year.12 This becomes the foundation for the annual review, and often, the senior mentor will perform the annual review as well.

During the annual review, the past year's expectations and performance are reviewed, and progress toward the next promotion or reward category should be clear. Both the institution and the individual should reassess priorities and responsibilities. Ideally, faculty should receive a written summary of their annual reviews and their expectations for the coming year.

Promotion is warranted by the record of accomplishment measured against expectations and institutional standards. The traditional promotion criterion of “national reputation” may not be readily transferred to clinician-educators, many of whom are most highly valued in their home environments. In some cases, the pursuit of a national reputation may significantly detract from local responsibilities. Nevertheless, contributions that achieve national recognition are desirable for promotion to full professor level, with the understanding that the entire range of contributions must be considered. If the academic institution has time limits prior to tenure decisions, these limits should be adjusted to account for childbearing, parenting, and other legitimate reasons for a constrained work schedule or leave of absence.

Promotion reviewers should, as much as possible, be true peers. The work of contemporary clinician-educators is sufficiently new and different that it may be difficult for traditional academicians to appreciate it. Accordingly, clinician-educator faculty should be represented on departmental and institutional appointment and promotion committees. Primary and secondary reviewers should evaluate the quality and impact rather than quantity of work produced, based on explicit criteria. The promotions committee should prepare a confidential summary statement of results for both successful and unsuccessful candidates. An appeals process should exist and be accessible and available to the candidate.

FACTORS TO EVALUATE IN THE PROMOTION PROCESS

Scholarship in Educational Methods and Teaching

This form of scholarship is most evident in the diligent and artful facilitation of clinical learners and organizational structures that support the teaching and learning enterprises. Recent work suggests that six knowledge domains are essential for excellence in clinical teaching clinical knowledge of medicine, patients, and the context of practice, and educational knowledge of learners, general principles of teaching, and case-based teaching scripts.29 The assessment of these domains will require the efficient, thorough, and reliable collection of information on the qualityquantity of individual clinical teachers’ contributions, including peer and learner assessments of the teacher's effectiveness. A variety of reliable and valid instruments are available for assessing teaching ability in both inpatient settings23,30,35 and outpatient settings.33,35 In some situations, the outcomes of the learners may also be a reliable index of an individual teacher.

Qualitative assessment should include a listing of teaching awards (local, regional, and national), learner evaluations, and expert review of teaching sessions. Clinical teaching should be observed directly or through videotape, with judgments based on objective criteria. Such activities are labor-intensive; institutions need to develop efficient mechanisms for ability-based evaluation of faculty.

To avoid potential bias, promotion data should be collected for all faculty by a standing committee on teaching excellence,9 rather than solely relying on the individual faculty member. Faculty should work together with the committee to maintain documentation of teaching activities. We suggest that this committee include people with expertise in adult learning and review all candidates for promotion. Reviewers should assess the scholarship of teaching contributions by explicit, standardized methods. For example, the institution should maintain a teaching activity record, with the help of the individual, and the individual should be responsible for maintaining a personal teaching portfolio, which requires the same level of integrity as is required for other scholarly contributions.

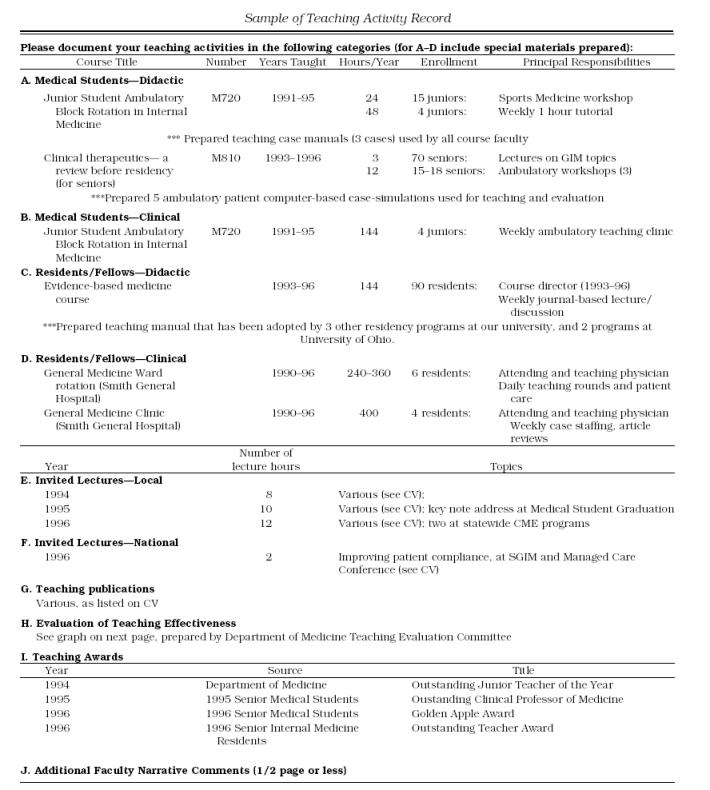

Teaching Activity Record

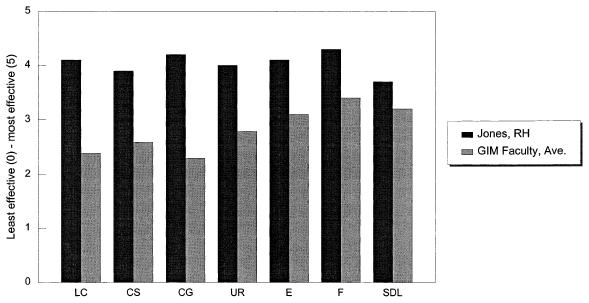

A concurrent teaching activity record is a record or list of courses taught, programs developed, materials produced, etc. The records can be viewed as an extension of the curriculum vitae, (see Appendix for an example) and benefits from tables and graphical displays (Figure 1). A teaching activity record should document teaching activities, products, and outcomes, and should become part of the academic department's management system. This record should include information regarding numbers of sessions, attendees, and hours taught, including small-group assignments, large-group assignments, lectures, clinical supervision, and participation in faculty-development workshops. A relative value scale for various teaching responsibilities can be used to document levels of involvement.36,37 For example, in a recent publication, mean weights were suggested as 2.0 for lecturing, 10.0 for preparing grand rounds, 2.0 for serving as an inpatient attending physician, and 4.0 for directing a course.36 By multiplying the number of hours spent on the task by its weight, the quantity and intensity of actual teaching can be assessed and compared. Further research is needed to determine the generalizability of relative value scales across institutions and disciplines. The record should also include qualitative assessments, such as evaluations of the effectiveness of teaching sessions (as judged by the learners and expert observers) and any peer or learner teaching awards. While faculty should be encouraged to create assignment-specific evaluation documents, standardized forms should be used whenever possible.

Figure 1.

Sample summary of clinical teaching performance evaluation by junior medical students. Cumulative, academic year 1995. Faculty name: Jones, Robert H. (N = 115). Location: Outpatient Teaching Clinic. Comparison Group: GIM Faculty Evaluations, average (N = 3,051). Prepared August 1, 1996. LC indicates learning climate; CS, control of session; CG, communication of goals; UR, understanding and retention; E, evaluation; F, feedback; SDL, self-directed learning. (Graph modified from the work of Debra K. Litzelman, MD, Indiana University School of Medicine.

Teaching Portfolio

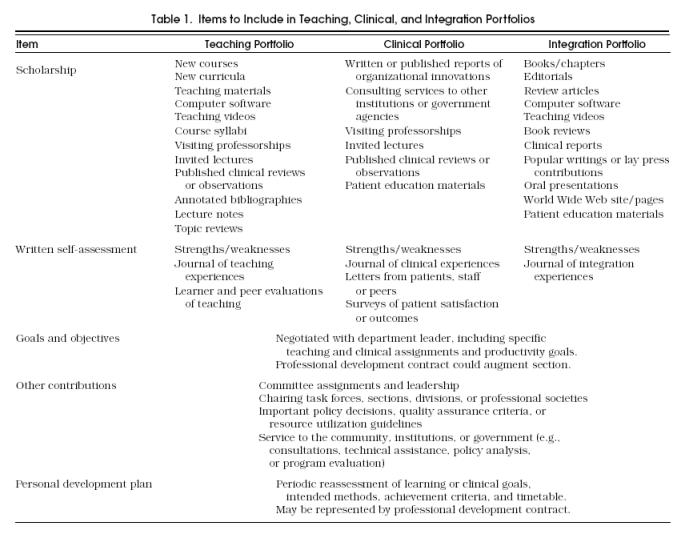

A teaching portfolio is a detailed aggregation of information and events representing scholarship. It contains a selected collection of material that serves as evidence of effective teaching, and should highlight the best contributions (both process and outcomes) of a person's activities (Table 1). The portfolio also indicates the meaning and significance of the listed teaching activities and reveals the degree of excellence in specified teaching activities. The individual faculty member is responsible for assembling these materials and is required to justify why each item was selected and in what way it constitutes evidence of effective teaching. For example, if a person aimed to develop a new ethics curriculum, the rationale, goals, curriculum development, teaching methods and materials, and course outcomes (evaluations) would be documented. These would not necessarily be of publication standard, but should be shown to be usable and useful in the institution and, ideally, in other institutions. A publication would definitely be an added criterion for scholarship in this area.

Table 1.

Items to Include in Teaching, Clinical, and Integration Portfolios

Portfolios can be used for promoting clinician-educators, selecting individuals for outstanding teaching awards or merit pay, and when applying for a new position. Portfolio generation is likely to promote faculty development and provide clinician-educators with a means of displaying and being rewarded for their educational knowledge and skills.

Scholarship in Clinical Practice Application

This scholarship is most apparent in the careful and artful practice of medicine and participation in the management of health services organizations (the clinician-manager). The assessment of clinical scholarship requires the efficient, thorough, and reliable collection of information on the quality and quantity of the work of individual clinicians.38 Evaluation of this type of scholarship is as necessary as any other.38,41 Also, a variety of clinical practice areas can be assessed with reliable and valid instruments, including clinical knowledge40,46 and humanistic behavior.39,47,48 Although instruments for assessing technical skills are lacking, development of new operating techniques or ways to expedite existing techniques should be considered. Analogous to the teaching record, institutions should monitor clinical activity records. In addition, clinicians should maintain their own personal clinical portfolio, detailed further in Table 1.

Clinical Activity Record

This record should document clinical activities (patient volume and clinical hours per year), results of any periodic patient satisfaction surveys or complaints,39,49 periodic assessments of clinical practice by colleagues (physician peers, residents, nurses, social workers, and support staff),38,41 performance on certificate or recertification examinations,40 continuing education, career development activities, the receipt of awards for clinical practice, service to the management of the practice, and scholarly products relating to clinical practice. Clinical competence may also be assessed by medical audits of the process and outcome of care as judged by predetermined standards, if such an approach can be shown to be sufficiently reliable.20,50

Scholarship of Integration

This scholarship is most apparent in the dissemination of new or reformulated clinical or teaching knowledge. Examples in this area of scholarship include authoring or editing books, chapters, reviews, editorials, and clinical reports, or other means of disseminating information. Similar to the other areas of scholarship, thorough and reliable information is necessary to evaluate an individual's work. Analogous to the teaching record, institutions should monitor integration activity records. In addition, clinicians should maintain their own personal integration portfolio, detailed in Table 1.

Integration Activity Record

This record may include a cataloging of original research activities, traditional publications, and grants; editorialships or other involvement in the process of disseminating information or teaching aids; and directorships of courses (undergraduate, predoctoral, residency, fellowship, and continuing medical education programs). The record should document integration activities (e.g., hours per year spent in reformulating or preparing information for dissemination, specific names or locations of publications or products, course attendance), the volume of distribution of products (e.g., sales of books, number of visits to a World Wide Web site, frequency of course offerings), and the receipt of awards for these activities.

Conclusions

This statement is designed to guide the promotion process for clinician-educators. It should serve as a resource for all institutions and departments to aid in examining or developing criteria for clinician-educator tracks.

Several important issues are not addressed, as their complexity is beyond the scope of this statement, or the issues are highly institution-specific: the definition, rights and privileges, and timing of tenure; the expected rate of progress for an individual faculty member; the number and composition of promotion tracks; the academic status of full-time clinicians, affiliated community-based faculty, or those whose teaching responsibilities are minimal; part-time faculty who may spend some time in teaching roles (some part-time faculty devote full professional effort [PT-FPE]51,52 to clinical teaching for those schools that promote PT-FPE faculty, these guidelines are applicable); gender and race differences in needs, career focus, and productivity53,55 and guidelines for assessing contributions of faculty who are primarily investigators or administrators (although many faculty members who concentrate their efforts on teaching and clinical tasks also spend some time in research, especially as it relates to educational programs or the types of patients they see in their own practices, and in administrative responsibilities. Ideally, medical schools would incorporate guidelines for assessing teaching and clinical contributions with the complementary guidelines for assessing research and administrative contributions).

In summary, actzive career management by both individual faculty and the institution is vital for successful promotion and tenure. We encourage the use of professional development contracts, emphasizing the service needs of the department as well as the career development needs of the individual faculty. Mutual understanding of responsibilities and career advancement expectations are critical, as is carrying forth a plan of feedback through semiannual to annual formative evaluation and summative evaluation at the time of promotion. Portfolios and activity records should be developed with guidance from the department and institution, stressing quality more than quantity. Data collection, facilitated by a department committee on teaching excellence, will help to standardize the review process and decrease potential bias. Finally, promotion committees should reevaluate their structure and function to ensure a rigorous, fair process.

Acknowledgments

These guidelines are the result of a careful 5-year process involving a number of SGIM members. Problems and solutions were identified by 60 people during a workshop at the 1991 annual meeting. This information was supplemented by automated literature searches, a survey of a random 10% of SGIM members in 1992, and a content analysis of currently used promotion criteria in U.S. academic departments of medicine. Feedback was obtained through the SGIM Education Committee, National Council, the Interest Group on faculty status of teacher-clinicians, and the Task Force on Clinician-Teacher. Authors involved with the original and earlier drafts of this statement include the following Interest Group Members: Norman Jensen, MD, (Interest Group Coordinator), Michael B. Jacobs, MD, (Co-coordinator), John Goodson, MD, Lee Goldman, MD, John Stoeckle, MD, Barbara Schuster, MD, Claudia Beghe, MD, Allan Prochazka, MD, MSc, Sandra Green, MD, Joe W. Ramsdell, MD, Michael D. Erdmann, MD, MS, Neal V. Dawson, MD, and Mariana Hewson, PhD. Other members of the interest group and the Society who played important roles in the production of this statement include Dennis Cope, MD, (Co-coordinator), Steve A. Schroeder, MD, Andrew Diehl, MD, Lynne Kirk, MD, Philip Katz, MD, Robert S. Dittus, MD, Raymond Mayewski, MD, Terrance J. Drake, MD, Carol Bates, MD, Wendy Levinson, MD, Peter R. Lichstein, MD, Janice M. Wood, MD, Robert Burack, MD, JudyAnn Bigby, MD, Eric Bass, MD, Eric Larson, MD, and Paul Ramsey, MD. Members of the 1996 Education Committee who have reviewed drafts of this statement include Ann Nattinger, MD, Auguste Fortin, MD, Linda Pinsky, MD, Ruth-Marie Fincher, MD, and Rebecca Wang-Cheng, MD.

Appendix

Sample of teaching activity Record

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman RH, Pozen JT, Rosencrans AL, et al. General internal medicine units in academic medical centers: their emergence and functions. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:233–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovejoy FH, Ledley FD, Nathan DG. Academic careers: choice and activity of graduates of a pediatric residency program 1974 1986. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 1992;104:180–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meislin HW, Spaite DW, Valenzuela TD. Meeting the goals of academia: characteristics of emergency medicine faculty academic work styles. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80891-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey RM, Wheby MS, Reynolds RE. Evaluating faculty clinical excellence in the academic health science center. Acad Med. 1993;68:813–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RF, Friedman PJ, Cassell GH, et al. Three views on faculty tenure in medical schools. Acad Med. 1993;68:588–93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickel J. The changing faces of promotion and tenure at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1991;66:249–56. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley WN, Stress JK. Faculty tracks and academic success. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:654–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-8-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parris M, Stemmler EJ. Development of clinician-educator faculty tracks at the University of Pennsylvania. J Med Educ. 1984;59:465–70. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman AL, Poldre P, Cohen R. Innovations in medical education. Evaluating clinical teachers for promotion. Acad Med. 1989;64:774–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey HJ, Sorensen L. Promotion of clinical faculty. Careers. 1991;7:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batshaw ML, Plotnick LP, Petty BG, Woolf PK, Mellits ED. Academic promotion at a medical school Experience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:741–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803243181204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodgewic S, Plotnick LP. Advancement and promotion: Managing the individual career. In: McGaghie WC, Frey JJ, editors. Handbook for the Academic Physician. New York: NY: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs MB. Guidelines for the evaluation and promotion of clinician-educators. Acad Med. 1993;68:126–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin CD, Levine HG, McCormick DP. Meeting the faculty development needs of generalist physicians in academia. Acad Med. 1995;70:S97–S103. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199501000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantor JC, Cohen AB, Barker DC, Shuster AL, Reynolds RC. Medical educator's views on medical education reform. JAMA. 1991;265:1002–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RF, Froom JD. Faculty and administrative views of problems in faculty evaluation. Acad Med. 1994;69:476–83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199406000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halperin EC. Is tenure irrelevant for academic clinicians? South Med J. 1995;88:1099–1106. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greer DS. Faculty rewards for the generalist clinician-teacher. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(s2):S53 8. doi: 10.1007/BF02600438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersdorf RG. It's report card time again. Acad Med. 1994;69:171–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyer EL. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Princeton: NJ: Princeton University Press; 1990. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professorate. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen NM. Guidelines for promotion of clinical teachers. SGIM News. 1993;16:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman RH, Alpert JJ, Green LA. Strengthening academic generalist departments and divisions. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(suppl 2):S90 8. doi: 10.1007/BF02598123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Menachem T, Estrada C, Young MJ, et al. Balancing service and education: improving internal medicine residencies in the managed care era. Am J Med. 1996;100:224–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xakellis GC, Gjerde CL. Ambulatory medical education: teachers’ activities, teaching cost, and resident satisfaction. Acad Med. 1995;70:702–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199508000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearl GW, Mainous AG. Physicians’ productivity and teaching responsibilities. Acad Med. 1993;68:166–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersdorf RG. Current and future directions for hospital and physician reimbursement. JAMA. 1985;256:2543–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K. Conducting research as a busy clinician-teacher or trainee. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:360–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02600048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gjerde CL, Colombo SE. Promotion criteria: perceptions of faculty members and departmental chairmen. J Med Educ. 1982;57:157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irby DM. What clinical teachers need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irby DM. Clinical teacher effectiveness in medicine. J Med Educ. 1978;53:808–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irby DM, Rakestraw P. Evaluating clinical teaching in medicine. J Med Educ. 1981;56:181–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skeff K. The evaluation of a method to improve the teaching performance of the attending physician. Am J Med. 1981;75:465–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsbottom-Lucier MT, Gillmore GM, Irby DM, Ramsey PG. Evaluation of clinical teaching by general internal medicine faculty in outpatient and inpatient settings. Acad Med. 1994;69:l52–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199402000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guyatt GH, Nishikawa J, Willan A. A measurement process for evaluating clinical teachers in internal medicine. Can Med Assoc J. 1993;149:1097–1102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hewson MG, Jensen NM. An inventory to improve clinical teaching performance in the general internal medicine clinic. Med Educ. 1990;24:518–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1990.tb02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bardes CL, Hayes JG. Are the teachers teaching? Measuring the educational activities of clinical faculty. Acad Med. 1995;70:111–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutton JJ. Medical education who does it and how do we pay for it. Keynote address, 12th Annual Meeting, Society of General Internal Medicine, Midwest Region. 1995 September 29. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267:958–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver MJ, Ow CL, Walker DJ, Degenhardt EF. A questionnaire for patients’ evaluation of their physicians’ humanistic behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:135–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02599758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramsey PG, Carline JD, Inui TS, et al. Predictive validity of certification by the American Board of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:719–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsey PG, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Inui TS, Larson EB, LoGerfo JP. Use of peer ratings to evaluate physician performance. JAMA. 1993;269:1655–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carline JD, Wenrich MD, Ramsey PG. Characteristics of ratings of physician competence by professional associates. Eval Health Prof. 1989;12:409–23. doi: 10.1177/016327878901200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Giles LM, Ramsey PG. Ratings of the performances of practicing internists by hospital-based registered nurses. Acad Med. 1993;68:680–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199309000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harber RJ, Avins AL. Do ratings on the American Board of Internal Medicine Resident Evaluation Form detect differences in clinical competence? J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:140–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02600028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramsey PG, Carline JD, Blank LL, Wenrich MD. Feasibility of hospital-based use of peer ratings to evaluate the performances of practicing physicians. Acad Med. 1996;71:364–70. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Risucci DA, Tortolani AJ, Ward RJ. Ratings of surgical residents by self-supervisors, and peers. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:519–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLeod PJ, Tamblyn R, Benaroya S, Snell L. Faculty ratings of resident humanism predict satisfaction in ambulatory medical clinics. J. Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:321–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02599179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linn LS, DiMatteo MR, Cope DW, Robbins A. Measuring physicians’ humanistic attitudes, values, and behaviors. Med Care. 1987;25:504–15. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delbanco TL. Enriching the doctor-patient relationship by inviting the patient's perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:414–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-5-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dans PE. Clinical peer review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:566–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Froom JD, Bickel J. Medical school policies for part-time faculty committees to full professional effort. Acad Med. 1996;71:91–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199601000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christiansen RG, Wark K, Levenstein JP. Attitudes of part-time community internal medicine faculty about their teaching. Acad Med. 1992;67:863–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199212000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carr P, Friedman RH, Moskowitz MA, Kazis LE, Weed HG. Research, academic rank, and compensation of women and men faculty in academic general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:418–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02599159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Towsend JM, Fulchon C. Minority faculty recruiting, retaining, and sustaining. Fam Med. 1994;26:612–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jonasson O. Women as leaders in organized surgery and surgical education. Arch Surg. 1993;128:618–21. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420180016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]