SYNOPSIS

Allocation of public health resources should be based, where feasible, on objective assessments of health status, burden of disease, injury, and disability, their preventability, and related costs. In this article, we first analyze traditional measures of the public’s health that address the burden of disease and disability and associated costs. Second, we discuss activities that are essential to protecting the public’s health but whose impact is difficult to measure. Third, we propose general characteristics of useful measures of the public’s health. We contend that expanding the repertoire of measures of the public’s health is a critical step in targeting attention and resources to improve health, stemming mounting health care costs, and slowing declining quality of life that threatens the nation’s future.

By the middle of the 21st century, the U.S. population is projected to increase by approximately 40% to more than 400 millions persons.1 More than 20% of the population will be over 65 years, an increase from 12.5% in 2003. Approximately half the U.S. population in 2050 will be white; the largest increases will be seen in Hispanic and Asian populations.1 Because of persisting inequities in health status, these demographic changes will have a dramatic impact on health. An older population will suffer from more chronic disease, even if age-specific prevalence of conditions remains stable. The projections for prevalent cases of Alzheimer’s disease, for example, will more than double by 2030.2 Similar projections have been made for obesity,3 diabetes mellitus,4 chronic lung disease,5 and other chronic conditions. In addition, age-adjusted quality of life as measured by healthy days has decreased over time.6

Whereas longer life, if accompanied by improved health in advanced years, will have only a slight impact on health costs,7 longer life with no improvements in health will cause increased use of new health care technologies and escalate spending, not only for direct medical care, but also for long-term care of older persons and those living with disabilities.8,9 Medicare spending has been projected to increase from 2% to 6% of the gross domestic product (GDP) from 2004 to 2050.10 In 2002, spending for health care in the United States was $1.6 trillion; when adjusted for inflation, this is a fivefold increase from 1970.11 Medicaid and Medicare alone accounted for one-third of these costs. Although national health expenditures took 10 years to grow from 12% of GDP in 1990 to 13.3 % in 2000, these expenditures took only one year to grow to 14.1% in 2001. The increasingly older age distribution in the United States is an indication that these costs will continue to increase in future years.1

The anticipated increase in health care costs and inequities12 in access to the benefits of our health system should stimulate vigorous dialogue regarding solutions. Rebalancing the investment portfolio to emphasize health protection and prevention of those conditions with high burden and cost is a logical strategy.13 However, successful efforts require developing and validating better measures of the public’s health and associated costs to guide rational decisions about the allocation of limited resources.

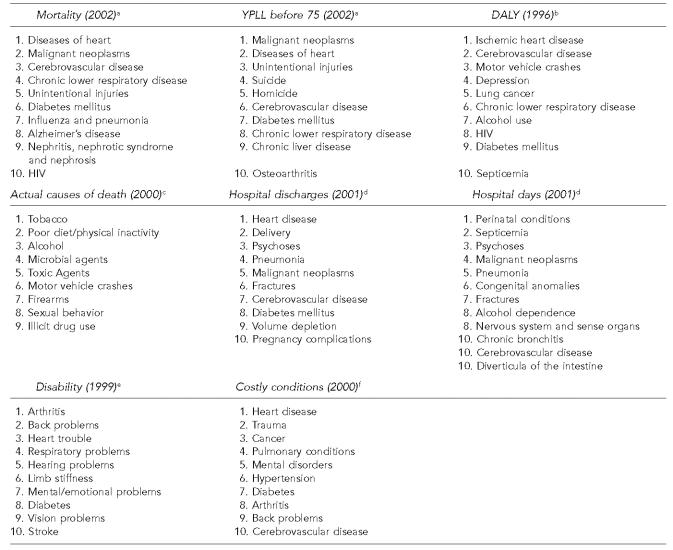

In 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as “… a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”14 Today, despite extensive analytic efforts to assess health more accurately, measures available to evaluate the health of populations continue to be morbidity, mortality, and disability. We analyzed selected traditional measures of public health, including morbidity, mortality, and disability, and their related costs, as well as summary measures of burden and quality of life, which can be used to prioritize conditions for attention (Figure). In this article, we discuss general characteristics of useful measures of the public’s health as well as activities that are essential to protect the public’s health even though their impact might be difficult to measure. Finally, we describe new measures needed to assess the public’s health and monitor the effectiveness of public health programs and practice.

Figure.

a National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2004. Hyattsville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 2004.

b McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJL, Marks JS. Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability-adjusted life years. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:415-23.

c Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000 [published erratum appears in JAMA 2005;293:293-4]. JAMA 2004;291:1238-45.

d Kozak LJ, Owings MF, Hall MJ. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2001 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13 2004:1-198.

e Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999 [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001:50(08):149]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50(07):120-5.

f Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004 Aug 25;Suppl Web Exclusives;W4-437-45 [cited 2005 Apr 4]. Available at: URL: http://content.healthaffairs.org

YPLL = years of potential life lost

DALY = disability-adjusted life years

Leading causes of public health burden using alternative measures of burden, United States

CURRENT MEASURES OF THE PUBLIC’S HEALTH

Mortality

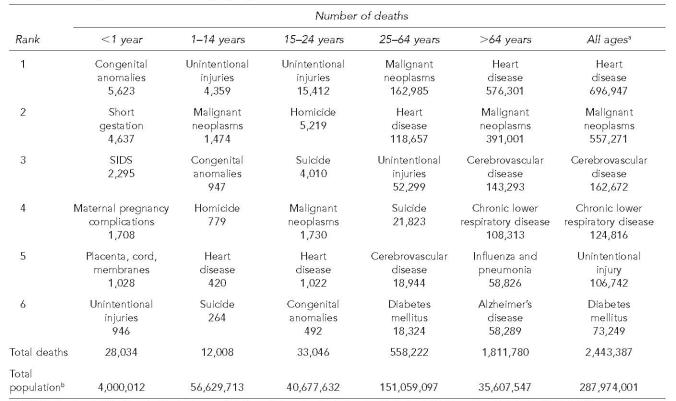

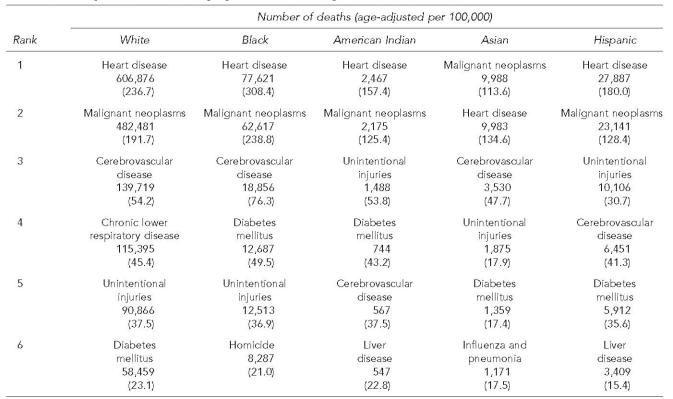

Numbers and rates of deaths have been used for centuries to measure burden and to compare the impact of diseases. For example, in the United States, chronic diseases—cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and diabetes—are leading causes of death, followed closely by unintentional injuries and influenza.15 Age-specific mortality rates provide additional insights that might influence policy decisions. For example, infant deaths are dominated by congenital anomalies, short gestation, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS); young adults are killed primarily by intentional and unintentional injuries (Table 1). Similarly, stratification of mortality data by race and ethnicity helps to quantify health disparities. For example, blacks suffer higher rates of death for almost all leading causes (Table 2).16 Of note, except for diabetes in Hispanics and unintentional injury in American Indians, both groups have lower rates than whites for the leading causes of death; Asians have the lowest rates for all major causes of death except cerebrovascular disease. As with other measures of burden, the designation of categories of death affects ranking. For example, if we combine injuries across all causes (motor-vehicle injuries, homicide, suicide, etc.), as cancer is combined across all sites, injuries would become the leading cause of premature mortality.

Table 1.

Leading causes of mortality by age, United States, 2002

SOURCE: Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Anderson RN, Scott C. Deaths: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2004 Oct 15;53:1-115.

Differences from totals of age groups are due to records with age unspecified.

National Center for Health Statistics. Estimates of the July 1, 2000–July 1, 2002, United States resident population from the Vintage 2002 postcensal series by year, age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin, prepared under a collaborative arrangement with the U.S. Census Bureau. 2003. [cited 2005 Oct 19]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/dvs/popbridge/popbridge.htm

SIDS 5 sudden infant death syndrome

Table 2.

Leading causes of mortality by race and ethnicity,a United States, 2002

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2004. Hyattsville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 2004.

Race and Hispanic origin are reported separately on the death certificate. Therefore, data shown by race (i.e., white, black, American Indian, and Asian or Pacific Islander) include persons of Hispanic or non-Hispanic origin. Data shown for Hispanic persons include all persons of Hispanic origin of any race.

Premature mortality, a measure of burden first proposed by Dempsey in 1947 to address the inadequacy of mortality in measuring the burden of tuberculosis, is another important way to quantify burden.17 In constructing a measure of premature death, an arbitrary limit to life is chosen, and the calculation of the difference between an age at death and this arbitrary limit is defined as the life lost as a result of that death. For example, in 2002, malignant neoplasms, heart disease, and unintentional injuries are the leading causes of premature mortality measured by years of potential life lost (YPLL) before age 75 years (Figure).16 Rankings are also affected by the arbitrary choice of a specific age to determine premature death, thus causing any death later than that age to contribute nothing to the burden of disease. This methodological problem is particularly influential if a large number of persons are living past the cutoff age with good quality of life.

Mortality rates might not directly reflect the contribution of preventable causes of death. In 1991, McGinnis and Foege proposed the concept of “actual causes of death” to emphasize the importance of the underlying (and usually preventable) risk factors that contribute to mortality.18 In fact, actual causes of death are more accurately characterized as measures of burden of risk. A recent update of their analysis reaffirmed that tobacco use together with poor diet and lack of exercise were major actual causes of death, followed by other modifiable behaviors (alcohol use, sexual practices, and drug use) and external causes (infections, toxins, motor vehicle crashes, and firearms [Figure]).19 Importantly, the 2004 analysis demonstrated that poor diet and physical inactivity, major contributors to the obesity epidemic, had increased as actual causes of death in the United States.

Morbidity

The number or rate of nonfatal outcomes (e.g., the number of incident cases) is not used as often as mortality in assessing disease burden. The only chronic, non-infectious condition for which the United States has national data for incident cases is cancer.20 Rates of hospitalization are sometimes used to estimate disease burden among a population. Hospitalization rates have the advantage of being relatively easy to obtain and are useful for certain analyses, but are biased indicators of burden for the majority of conditions. For example, the increasing use of outpatient treatment for conditions previously requiring hospitalization can substantially affect the utility of these data for assessing burden. In the United States, heart disease is the leading cause of entry hospitalization, followed in order by childbirth, psychoses, pneumonia, cancer, and fractures.21

Measurement of disability provides another morbidity dimension to the burden of nonfatal health problems. Bone and joint pain, most often caused by arthritis, is the leading cause of disability, followed closely by chronic diseases (heart disease, lung problems, diabetes, and stroke), mental health disorders, and hearing and vision disorders.22 As therapy improves and survival lengthens, the prevalence of disabling conditions will likely increase. Successful treatments for cancers and for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection illustrate this phenomenon.

Summary measures

Summary measures are employed to attempt to assess overall health status of a population. These measures usually combine morbidity, mortality, and disability data but can also reflect perceived quality of life or functional status. For example, physical functioning, mental and emotional well-being, social functioning, general health perceptions, pain, energy, and vitality have all been used to assess health status.23 Quality-of-life measures are especially critical for conditions that cause considerable suffering but limited numbers of deaths.

Disability-adjusted life years (DALY) is a summary measure of burden of disease among populations that combines mortality and morbidity measures. The calculation of DALY usually assesses nonfatal outcomes as part of the burden and requires a standard means of weighing different types and severities of disability.24 In the United States, heart disease accounts for the largest fraction of lost DALY for both men and women. HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), alcohol abuse, and depression are also important causes of lost DALY, with depression being the second leading cause for women.25 Although summary estimates of burden such as quality-adjusted life years have been described, their use in the United States for measuring population burden is limited.26

Cost

The economic costs incurred as a consequence of a health condition are a key summary measure of economic burden. Estimates of the economic burden can be used as a basis for resource allocations. Although data from multiple studies that examine cost of illness information for different conditions are available, considerable variability in methods and data sources make comparisons difficult. Ideally, comparative assessment of burden would be derived from a single data source with health care utilization and expenditure information across a range of conditions. Data from the 1997 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which provides estimates of national health care spending among the noninstitutionalized U.S. population, indicate that treatment of persons with heart disease, cancer, or suffering from trauma accounts for approximately one-third of all direct medical costs, and that chronic conditions account for the majority of the remaining costs.27 An updated analysis using 2000 MEPS data reveals that although heart disease is still the most costly condition, trauma precedes cancer in ranking, followed by pulmonary disease and mental disorders.28 The estimates do not provide a comprehensive measure of economic burden because the MEPS data do not include indirect costs associated with disease-related disability and productivity loss.

Still, costs are an incomplete measure of economic burden, failing to capture important aspects of deterioration in health-related quality of life (e.g., reduced functioning, pain and suffering, and emotional and psychological impact on family and friends). In addition, health care utilization and expenditure data exclude untreated illness. These exclusions can underestimate morbidity, especially among the disadvantaged whose circumstances often limit utilization of health care.

LIMITATIONS ON USING BURDEN TO MEASURE THE PUBLIC’S HEALTH

A reexamination of the Figure shows that a reliance on a single measure of public health burden may be misleading. While the latest available data are from different years, the change in rankings for different cases can be instructive. For example, suicide and homicide (intentional injuries) do not appear in leading causes for total mortality, but these events are very important as causes of premature death (as defined by YPLL before 75). While depression may not be the cause of death, it responsible for the fourth largest source of disability, as defined by DALYs.

A second point to note from the Figure is that while “rankings” may be very attractive to the general public and to the media, their use may also oversimplify matters. For example, two conditions may be ranked very differently due to the conditions in the comparison but be very similar on an absolute scale.

In addition to the limitation of single measures, consensus on the best measures of the public’s health might never exist. This is not surprising because measurements are used to accomplish diverse functions (e.g., population health assessment, evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions, formulation of health policies, and projection of future resource need). The choice of measures might reflect individual and societal values. For example, emphasis on measures of morbidity such as incidence or disability implies that value is placed on suffering as well as death. Use of YPLL implies that extra value is placed on premature deaths. Measures that do not capture broader aspects of burden (e.g., pain and suffering, deterioration in quality of life, and emotional and physical impacts on families) imply that these values are not as important as traditional measures.29 Finally, even the best measures of burden incompletely reflect key elements of public health practice such as emergency preparedness, and they do not address the availability of effective preventive practices (e.g., immunization or fluoridation).

DIFFICULT-TO-MEASURE ACTIVITIES ESSENTIAL TO THE PUBLIC’S HEALTH

In certain cases, data to assess burden of disease are not readily available. For example, in the United States with the exception of cancer, no ongoing reliable system exists to assess the morbidity burden of chronic diseases at the state and local levels, even though these conditions have a substantial impact on the population’s health. Even more problematic is measuring the effect of activities, mainly supported through the public health system, that directly or indirectly influence population health that are not encompassed by measures of burden. For example, emergency preparedness (the capacity to mount an appropriate and effective response to an acute disaster, a terrorist threat, an exposure to an environmental or occupational hazard, or an outbreak of disease) is essential to the public’s health.30 However, the traditional measurements of health status are not designed to assess preparedness. Similarly, we do not have measures to assess the strength and effectiveness of the public health system (e.g., public health surveillance and health monitoring).31

In other instances, measures of burden may not capture the beneficial health effects of successful programs that must be sustained to protect health. For example, immunization programs in the United States have dramatically reduced the burden of certain infectious diseases. Using available measures of the current burden of these diseases alone as criteria for investment in immunization activities would put our residents at risk for diseases that still circulate globally.

Other dimensions of an effective public health system are absent from the standard metrics for assessing population health. For example, measures of environmental quality (e.g., air- and water-quality monitoring),32 mental health (mental unhealthy days),33 and socioeconomic status34 exist, but are limited in scope and precision, and most important, are not well integrated into public health practice. For example, in most states, departments of the environment are administered separately from departments of health and public health. Mental health services tend to be separate from public health at all levels of government.

CHARACTERISTICS OF USEFUL MEASURES OF THE PUBLIC’S HEALTH

Optimally, a measure of population health should have certain characteristics to ensure its usefulness. First, useful measures of the effectiveness of public health interventions could detect either an absolute or a relative change in health status over time. For example, the mortality rate, while commonly used and roughly comparable around the world, reflects only an absolute change. So if the infant mortality rate is 10 (per 1,000) in one location in one month and 12 (per 1,000) the next, the absolute increase in infant mortality is 2 per 1,000. However, a percentage change (e.g., 12/10 or 120%) suggests the relative magnitude of the change (e.g., as for economics, the growth in the GDP is reported).

Second, a key concept for the adequacy of a measure is validity, the extent to which the indicator measures what it purports to measure.35 Face validity, the characteristic of whether the measure appears to represent health status (e.g., personal self report of health as excellent, good, fair, or poor), might not be as appropriate for this purpose as construct validity, the question of whether a given measure will reflect objectively either health status or a change in health status (e.g., a clinical measurement of height and weight).

Third, the population health measure should be sensitive to major health policy changes. For example, if taxation on tobacco is increased, youth initiation may be a more immediate measure of effect than, say adult cessation. In other areas of population health (e.g., mental health, chronic disease) the challenge is to develop proximal measures that are linked to more distal improvements in health.

Fourth, the measure should be reliable, stable over time, and equivalent across settings. If the measure is used repeatedly in the same circumstances, will it yield the same results? In the case of mortality, widespread use of ICD codes has served to increase this reliability and stability, even though the categorization may miss relevant nuances. For summary measures where personal assessments of health or quality of life are used, reliability may suffer. For example, self-rated health, while useful from a societal standpoint,36 may not be comparable from one population to another. Family, community, and other contexts can affect self-reported data substantially. Persons living with a disability, but in a supportive family and community environment, may rate their health as high compared with other non-disabled persons in less supportive environments.

IMPROVING THE PUBLIC’S HEALTH: DEVELOPING NEW MEASURES OF PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAM ASSESSMENT

Traditionally, health goals have been framed as reductions in the occurrence of disease, disability, injury, and death rates. Although these measures are critical, they represent only negative outcomes that we all hope to avoid or delay as long as possible. These measures are no longer adequate. We have to determine, investigate, track, and act on those aspects of health that are becoming increasingly influential as ways in which U.S. residents think about health. People’s thoughts about health, often framed as aspirations, come from the contexts of their lives. We must develop measures that enable us to assess health as defined by WHO in 1946.14

To this end, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has proposed specific goals for improving health so that in the future, the health of U.S. residents is improved measurably.37 Moreover, those improvements will be perceived by people to directly affect their ability to achieve the full quality of life to which they aspire. These goals have motivated CDC both to invest in research on measures of burden and to investigate the public health use of nontraditional measures of health such as social capital38 and assess the feasibility of the development of appropriate metrics of disease burden in these areas.39

For infants and toddlers, the critical concerns are related to growth, cognitive and physical development, and preventable death. At present, childhood goals focus on learning, healthy connections to family, developing friendships and social skills, continued appropriate growth and development, and preventable death. Health for adolescents should be reflected by healthy weight, appropriate levels of physical activity, strong and healthy social connections to family, peers, school, or community organizations, and healthy behavioral choices (e.g., drug, alcohol, and tobacco abstinence). For younger adults, measures of full participation and satisfaction both with work and with family life are needed. For older adults, measures are needed for activity, independence, and satisfactory social leisure activities.

The effect of social relationships and cohesion on health is important in nearly all life stages at both the individual and community levels. Measuring these social relationships and their impact on health is challenging.40 Likewise, measurement is needed of environmental and behavioral protective factors in populations. For example, progress on health status could be monitored by measuring the proportion of U.S. residents: (1) living in cohesive communities designed to make healthful living easier, safer, and enjoyable; (2) working in settings free from hazardous exposures and safety risks and that also promote healthy choices; and (3) sending their children to schools where education about health, including physical education and food services, encourages the formation of healthy behaviors.

Measurement of disease burden is informative but falls short of the needs in public health. Assessment of programs and tracking accountability will not only require use of multiple measures of burden, but also practical and useful measures of both essential public health services and positive health attributes and well-being.41 Useful tools for public health must be readily available, easy to use, and consistent across time and place. As a result, we must balance the need for increasing amounts of data with the ability of those in health to process those data in an effective and timely manner.

If the United States accepts the vision of health articulated by WHO in 1946 and is committed to the achievement of optimal health for its citizens, it must develop and use the tools that will measure progress toward that burden. The process of developing these tools requires agreement with partners in state and local public health as well as international collaborators such as WHO on both metrics and data standards. Development of effective tools also requires research and evaluation that will engage partners not only in government but also academia and the private sector. The CDC is committed to this new approach to measuring health, but the agency cannot act alone and will seek collaboration in this effort.

In the 20th century, tremendous advances were made in the health of the U.S. population. Today, we not only propose a better use of measures of burden, but also argue for a shift toward measures of health—the state of physical, mental, and social well-being articulated by WHO in 1946. The science necessary to direct such a shift has not emerged, and the societal will to foster that science has lagged.

Even if scientific developments were well developed and political will were supportive, public health practitioners would need to arrive at consensus on the essential set of population health measures. Such a consensus process might involve demonstrating the science underlying potential measures, illustrating their utility in developed and developing countries, assessing their utility in measuring disparities in health, and incorporating the perspectives of various stakeholders. This would involve building on existing partnerships (e.g., as exist today among WHO and partner nations) as well as development of new partners. With the framework proposed in this article, the health community can focus prevention and control efforts more precisely and measure the impact of those efforts more accurately. It is incumbent on the medical and public health communities to provide joint leadership and make the expansion and use of appropriate measures of the public’s health a societal priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sajal K. Chattopadhyay, Phaedra S. Corso, Scott D. Grosse, David H. Howard, Richard J. Klein, Diane M. Makuc, and Kaushik Mukhopadhaya for conceptual contributions and provision of data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Census Bureau (US) Projections of the resident population by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1999 to 2100 (Middle Series). Washington: Census Bureau, Population Projections Program, Population Division. [cited 2004 Nov 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/detail/d2001_10.pdf, http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/detail/d2021_30.pdf, http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/detail/d2031_40.pdf, and http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/detail/d2041_50.pdf.

- 2.Brookmeyer F, Gray S, Lawas C. Projections of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1337–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witt L. Why we’re losing the war against obesity. Am Demogr. 2003 Dec;25:27–31. 2004 Jan. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle JP, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KM, Hoerger TJ, Geiss LS, Chen H, et al. Projections of diabetes burden through 2050. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1936–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubitz J, Beebe J, Baker C. Longevity and Medicare expenditures. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:999–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504133321506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauly M. Should we be worried about high real medical spending in the United States? Health Affairs 2003 Jan 8; Suppl Web Exclusives;W3-15-27. [cited 2005 Apr 4]. Available from: URL: http://content.healthaffairs.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee R, Edwards R. The fiscal impact of population aging in the US: assessing the uncertainties. In: James Poterba., editor. Tax policy and the economy. Vol. 16. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research/MIT Press; 2002. pp. 141–181. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee R, Miller T. An approach to forecasting health expenditures, with application to the U.S. Medicare system. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1365–86. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levit K, Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A, Health Accounts Team Health spending rebound continues in 2002. Health Affairs. 2004;23:147–59. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health and Human Services (US); Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2010 progress reviews. [cited 2004 Nov 4]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/PROGRVW/

- 13.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference; New York. 1946. Jun 19–22, signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered in to force on 7 April 1948. Also available from: URL: http://www.who.int/about/definition. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Anderson RN, Scott C. Deaths: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004;53:1–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2004. [cited 2005 Apr 4];Hyattsville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. 2004 Available from: http//www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dempsey M. Decline in tuberculosis. The death rate fails to tell the entire story. Am Rev Tuberculosis. 1947;56:157–64. doi: 10.1164/art.1947.56.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;217:2207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [published erratum appears in JAMA 2005;293:293-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. Department of Health and Human Services (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Cancer Institute United States cancer statistics. Web-based incidence and mortality reports 1999–2001. 2004. [cited 2005 Jul 5]. Atlanta: Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs.

- 21.Kozak LJ, Owings MF, Hall MJ. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2001 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat. 2004;13:1–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999. [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001:50(08):149] 2001;50(07):120–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohr KN. Applications of health status assessment measures in clinical practice: overview of the Third Conference on Advances in Health Status Assessment. Med Care. 1992;30(5 Suppl):MS1–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199205001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray CJL. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis of disability-adjusted life years. Bull WHO. 1994;72:429–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJL, Marks JS. Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability-adjusted life years. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kominski GF, Simon PH, Ho A, Luck J, Lim YW, Fielding JE. Assessing the burden of disease and injury in Los Angeles County using disability-adjusted life years. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:185–91. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50125-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen JW, Krauss NA. Spending and service use among people with the fifteen most costly medical conditions. Health Affairs. 2003;22:129–38. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004 Aug 25;Suppl Web Exclusives;W4-437-45. [cited 2005 Apr 4]. Available from: URL: http://content.healthaffairs.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kirschstein R. Disease-specific estimates of direct and indirect costs of illness and NIH support. Fiscal year 2000 update; 2000 Feb. [cited 2005 Apr 4]. Available from: URL: http://ospp.od.nih.gov/ecostudies/COIreportweb.htm.

- 30.Assessment of the epidemiologic capacity in state and territorial health departments—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1049–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thacker SB, Stroup DF. Public health surveillance. In: Brownson RC, Petitti DB, editors. Applied epidemiology. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2006. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Parrish RG, Anderson HA. Surveillance in environmental public health: issues, systems, and sources. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:633–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahran HS, Kobau R, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Giles WH, Lando J. Self-reported frequent mental distress among adults—United States, 1993–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:963–6. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5341.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieger N, Zierler S, Hogan JW, Waterman P, Chen J, Lemieux K, et al. Geocoding and measurement of neighborhood socioeconomic position: a U.S. perspective. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 147–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan A. The conduct of inquiry. San Francisco: Chandler Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson DE, Powell-Griner E, Town M, Kovar MG. A comparison of national estimates from the National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1335–41. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) About CDC: goals. [cited 2005 Jul 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/about/goals.

- 38.Kawachi I. Social cohesion and health. In: Tarlov AR, St. Peter RF, editors. The society and population health reader. a state and community perspective. Volume II. New York: The New Press; 2000. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman LF. St. Peter RF. Social networks and health: the bonds that heal. In: Tarlov AR, editor; The society and population health reader. a state and community perspective. II. New York: The New Press; 2000. pp. p. 259–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade D, Schwarz N, Stone A. Toward national well-being accounts. AEA papers and proceedings. Am Economic Rev. 2004;94:429–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Achievements in public health, 1990–1999: changes in the public health system [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49(01):23] MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:1141–7. [Google Scholar]