Abstract

The imprinted mouse gene Meg1/Grb10 is expres sed from maternal alleles in almost all tissues and organs, except in the brain, where it is expressed biallelically, and the paternal allele is expressed preferentially in adulthood. In contrast, the human GRB10 gene shows equal biallelic expression in almost all tissues and organs, while it is almost always expressed paternally in the fetal brain. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the complex imprinting patterns among the different tissues and organs of humans and mice, we analyzed in detail both the genomic structures and tissue-specific expression profiles of these species. Experiments using 5′-RACE and RT–PCR demonstrated the existence in both humans and mice of novel brain- specific promoters, in which only the paternal allele was active. The promoters were located in the primary differentially methylated regions. Interest ingly, CTCF-binding sites were found only in the mouse promoter region where CTCF showed DNA methylation-sensitive binding activity. Thus, the insulator function of CTCF might cause reciprocal maternal expression of the Meg1/Grb10 gene from another upstream promoter in the mouse, whereas the human upstream promoter is active in both parental alleles due to the lack of the corresponding insulator sequence in this region.

INTRODUCTION

The Meg1/Grb10 gene was identified as a maternally expressed gene (Meg) using a subtractive protocol that used androgenetic embryos and normal, fertilized embryos (1). The Meg1/Grb10 gene encodes an adaptor protein Grb10, which functions as a putative inhibitor of signal transduction from the insulin receptor and/or insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (2–6). Therefore, it is likely that Meg1/Grb10 plays an inhibitory role in mouse development. It is also known that maternal duplication of mouse proximal chromosome 11, which contains Meg1/Grb10, causes prenatal growth retardation, while paternal duplication of the same region promotes prenatal growth (7). The human syntenic homologous gene, GRB10, is located on the short arm of human chromosome 7 (8), and maternal disomies of this chromosome cause perinatal growth retardation in Silver–Russell syndrome (SRS) (9–12). Therefore, GRB10 appears to be a good candidate for the etiology of this disease. However, no significant GRB10 mutations in SRS patients have been identified to date (13,14). In contrast to the maternal expression of mouse Meg1/Grb10, human GRB10 shows biallelic expression in almost all tissues and organs, and shows only paternal expression in the fetal brain (13,14). These expression profiles do not corroborate the idea of overexpression of the maternal growth inhibitory gene due to maternal disomies in the etiology of SRS.

Recently, it was discovered that the mouse Meg1/Grb10 gene has biallelic expression in the brain (15), which suggests that although the imprinting regulatory pathways of the gene homologs in mice and humans are different, they share common features. Thus, the common paternal allele activation pattern in the brain and differential expression in other tissues and organs from the maternal allele in mice and biparental alleles in humans provide a model for the regulation of monoallelic expression in imprinted genes. Based on extensive analyses of gene expression and genomic sequences, we propose a working model of regulation for these imprinted genes that encompasses a combination of tissue-specific promoters and species-specific insulator sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

5′-RACE

RNA samples were prepared from 9.5 days post-coitum (d.p.c.) mouse embryos and multiple tissues of adult mice using Isogen (Nippon Gene), as described previously (16). 5′-RACE–PCR was conducted using the Smart Race cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Two micrograms of total RNA of mouse tissues or 0.5 µg of poly(A) RNA from human tissues (Clontech) were reverse transcribed with PowerScript RT (Clontech) using the Smart II A oligonucleotide and 5′-RACE CDS primer. PCR was performed with either the antisense primer from mouse exon 3 (5′-AGTATCAGTATCAGACTGCATGTT-3′) or from human exon 2 (5′-GTCCTGGTCCTGCCGGGTCTTGTTG-3′) and the UPM primer designed in the extended template (the Smart II A oligonucleotide) to the 5′ sites of the cDNA (Clontech). The PCR products were subcloned into pGEM T-easy plasmids (Promega) and sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit and the ABI Prism 3100 Sequencer.

Allele-specific expression analysis of individual Grb10 splicing variants

Splice variant-specific PCR amplification consisted of 35 cycles at 96°C for 15 s, 60°C for 20 s and 72°C for 60 s in a Perkin Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 9600 with the following gene-specific primers: mouse Meg1/Grb10 exon 1a, 5′-CACGAAGTTTCCGCGCA-3′ and 5′-AGTATCAGTATCAGACTGCATGTTG-3′; mouse Meg1/Grb10 exon 1b, 5′-GCGATCATTCGTCTCTGAGC-3′ and 5′-AGTATCAGTATCAGACTGCATGTTG-3′; mouse Meg1/Grb10 common region (exons 2 and 3), 5′-TCCAAGTGGAGAGTACCATGC-3′ and 5′-TACGGATCTGCTCATCTTCG-3′; human GRB10 un1, 5′-CCGTGGAAATGTGATAAGAGC-3′ and 5′-GTCCTGGTCCTGCCGGGTCTTGTTG-3′; human GRB10 un2, 5′-GGCGCACACGCAGCGAC-3′ and 5′-GTCCTGGTCCTGCCGGGTCTTGTTG-3′; human GRB10 common region (exons 2 and 3), 5′-GTCAGACACGGTGCCCCTCCT-3′ and 5′-CTGGTCTTCCTCCTGAAGGCGC-3′.

DNA polymorphisms in the Meg1/Grb10 genes of mouse strains JF1 and C57BL/6 were detected by restriction fragment length polymorphism. The PCR amplification consisted of 30 cycles at 96°C for 15 s, 65°C for 20 s and 72°C for 60 s in a Perkin Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 9600. The primers used were 5′-CTTGATACCACCCAGAAAGTCTG-3′ and 5′-AACCCAAAGCATTTGGCAG-3′. The PCR products were digested with HpaII.

Bisulfite methylation assay

Genomic DNA samples were prepared from 9.5 d.p.c. mouse embryos and multiple tissues of adult mice using Isogen (Nippon Gene), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bisulfite treatment was performed as described previously (17). The bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified by PCR using the primer pairs: CpG-1a, 5′-GGGGTTTAATATTAAGTTTGAGGG-3′ and 5′-CCTTATAAAAATCACCTATAACTCTCC-3′; CpG-1b, 5′-GAGAAGATATGTTGAAGTT ATGGTG-3′ and 5′-TAAATACAATTACTACTTATTACATAATATC-3′. The PCR products were subcloned and sequenced as described above.

Gel shift assay

Whole cell extracts were prepared from adult mouse tissues, as described previously (18). The mouse recombinant CTCF protein (19) was synthesized by a coupled in vitro transcription/translation reaction using the TNT T7 Quick System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The gel shift assay was carried out using the GelShift Assay Core System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The following oligonucleotide duplexes were used: Meg1 repeat, 5′-GCGTGTCGGGCTCGCGTTGGCGCGTGCCGGCGCGTGCCGA-3′; FII, 5′-TGTAATTACGTCCCTCCCCCGCTAGGGGGCAGCAGCGAGCCGC-3′; SP1, 5′-ATT CGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′; AP1, 5′-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′. Methylation of the duplexes was carried out using SssI methylase (New England Biolabs) according to the supplier’s instructions. The methylation reaction was monitored by digestion of the duplexes with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HhaI (GCGC recognition site).

RESULTS

Identification of brain-specific, paternally expressed transcripts from novel promoters in both humans and mice

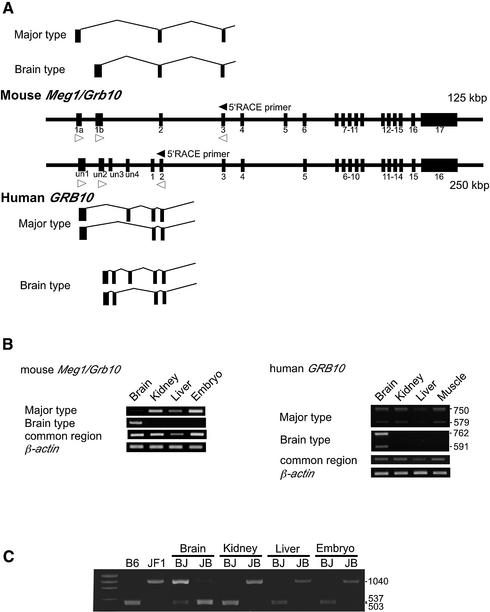

Maternal expression of mouse Meg1/Grb10 was observed in the embryos, adult kidney, liver and muscle tissues (1), whereas biallelic expression of human GRB10 was observed in these tissues (13,14). Biallelic, but strongly paternally biased, GRB10 expression was observed in human fetal brains (13,14). A similar situation was observed in the mouse. The Meg1/Grb10 gene was expressed biallelically in the mouse brain (15), but expression was strongly paternally biased in the adult (see Fig. 1C). We performed 5′-RACE from exon 3 of mouse Meg1/Grb10 and exon 2 of human GRB10 (Fig. 1A, black arrowheads) on tissue samples from embryos, kidneys and brains (adult brain of mouse and fetal brain of human). We isolated brain-specific transcripts that contained unique 5′-end sequences in both humans and mice (Fig. 1A, Brain type). Based on comparisons of these sequences with the published genomic sequences (GenBank accession nos AC004920 and AL663087), we identified the novel exon 1b as the brain-specific first exon in the mouse (Fig. 1A, upper part) and we identified unusual exons previously called un2 (upstream non-coding 2) and un3 (14) as the brain-specific first and second exons in humans (Fig. 1A, lower part). Exons un2 and un3 were previously registered as parts of the 5′-end sequence of a transcript isolated from human testis (GenBank accession no. AJ271366), but they did not appear in transcripts from other tissues or organs (14). All five of the isolated mouse clones had the same length as exon 1b, which suggests that this sequence includes a transcription start site. Human clones that contained the longest 5′-end sequence had sequence identity with the reported sequence (20).

Figure 1.

Two types of transcript from mouse Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10. (A) Brain-specific transcripts (Brain type) are identified by 5′-RACE from exon 3 of the mouse Meg1/Grb10 gene and exon 2 of the human GRB10 gene, as well as the major types in both humans and mice, as described previously. Black and white arrowheads indicate the positions and directions of the 5′-RACE and RT–PCR primers [see (B)], respectively. (B) Exon-specific RT–PCR experiments show that the transcripts in the brain are transcribed mainly from exon 1b in the mouse and exon un2 in the human, while those in other tissues are transcribed exclusively from mouse exon 1a and human exon un1. The primers used are shown in Materials and Methods. No other spliced forms of transcripts were detected in the mouse, whereas two types of transcripts with or without the un4 exon were detected in the human. The results of the RT–PCR between exons 2 and 3 in both humans and mice, which are common to the two types of transcripts, indicate that the relative expression levels in the brains are almost identical to those in other tissues and organs of both humans and mice. β-actin was measured as the control for the RT–PCR. (C) Different parental origins of the two types of transcript in the mouse. In contrast to the maternal expression of mouse Meg1/Grb10 in embryos, adult kidneys and liver, as previously published, Meg1/Grb10 was expressed mainly from the paternal allele in adult brains. BJ, (B6 mother × JF1 father) F1; JB, (JF1 father × B6 mother) F1.

In almost all of the tissues and organs, the major transcripts were transcribed from the previously identified mouse exon 1a and human exon un1 (14). We confirmed the transcription start sites of mouse exon 1a in more than 10 clones, but we could not isolate full-length clones of human exon un1 because it was too long to be determined by 5′-RACE. In humans, transcripts with or without exon un4 were observed. The open reading frame of mouse Meg1/Grb10 started from exon 3, and the human GRB10 had two possible translation start sites in exons 1 and 3 (see Fig. 3A, indicated by ATGs). Therefore, differential usage of the first exons does not influence the structures of the protein products.

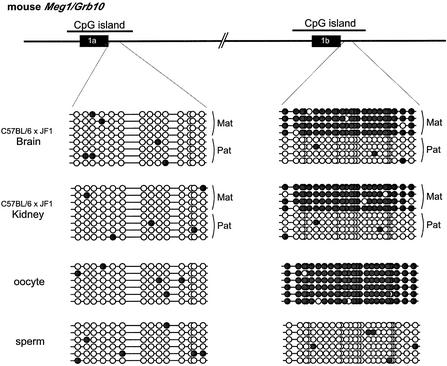

Figure 3.

Comparison of the human and mouse promoter regions. (A) The two promoter regions that are located in the CpG islands show high sequence homologies between humans and mice, with the exception of the 600 bp mouse-specific tandem repeat in the Peg promoter region. Putative translation start sites are indicated by ATG. DNA homologies between these regions were calculated using the program VISTA, which is based on moving a user-specified window (100 bp in this work) over the entire alignment and calculating the percent identity over the window at each base pair. (B) Twelve repeats of the 10 bp motif GGCGCGTG(C/T)T are observed in the mouse-specific region. The 40 bp sequence (boxed) was used as the probe in the gel shift assays (see Fig. 4, Meg1 repeat)

The RT–PCR products from the mouse exon 1a and 3 primers were detected in all samples, albeit at low levels in the brain, whereas brain-specific RT–PCR products were detected with the exon 1b and 3 primers (Fig. 1A, white arrowheads in the upper part). These results confirm the results of the 5′-RACE (Fig. 1B, left part). RT–PCR between primers in mouse exons 2 and 3, which amplified the common region of the two transcripts, showed that the level of expression in the brain was similar to that in other organs. Analysis of the DNA polymorphisms between the JF1 and B6 mouse strains clearly showed that while paternal expression predominated in the brain, expression in other organs was exclusively maternal (Fig. 1C). These results are consistent with the previous analysis of maternal and paternal duplications of proximal chromosome 11, on which Meg1/Grb10 is located (1,7). Contrary to the maternal expression patterns in embryos and certain adult tissues, this gene is biallelically expressed in the brain (15), but the contribution of the paternal allele is apparently increased in the neonatal brain compared to the embryonal brain, as shown in Figure 1C. These results demonstrate that there are two promoter regions upstream of exons 1a and 1b in the mouse Meg1/Grb10 gene; the first region modulates maternal expression (Meg promoter) and the second region modulates paternal expression (Peg promoter). Thus, the differences in imprinted gene expression patterns between the brain and other organs can be explained by differential usage of the two promoters. Brain-specific transcripts might be derived from alternative splicing of the major transcripts. This is unlikely, however, because there was no band corresponding to a transcript containing both exons 1a and 1b in the RT–PCR experiment between exons 1a and 3 and there is no evidence of exons of this gene further upstream.

The major transcripts from exon un1 and the fetal brain-specific transcripts from exon un2 (Fig. 1A, white arrowheads in the lower part) were also confirmed by RT–PCR in humans (Fig. 1B, right). Previously, it was reported that human GRB10 showed mainly paternal expression in the fetal brain and biallelic expression in other organs (13,14). We also confirmed the expression profiles in the corresponding samples (data not shown). Therefore, we propose that the fetal brain-specific promoter region upstream of exon un2 is active only in the paternal alleles of humans. Furthermore, in contrast to the mouse Meg promoter, a major human promoter upstream of exon un1 shows biallelic expression patterns.

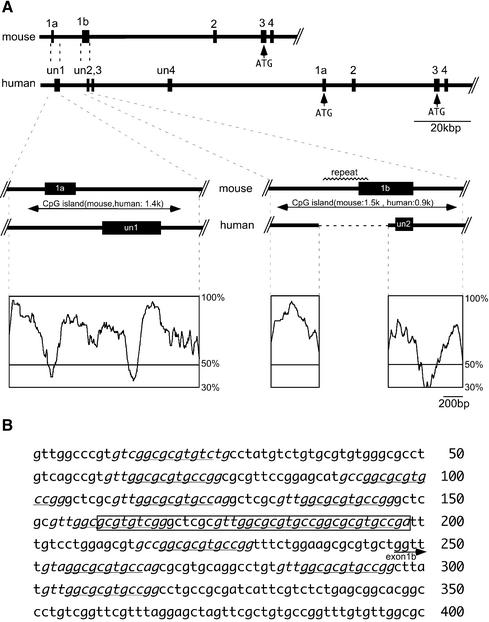

Differential methylation statuses of two CpG islands that overlap two distinct promoters

Both the human and mouse promoter regions were located within CpG islands (Figs 2 and 3). Using the bisulfite sequencing method, we examined the DNA methylation statuses of these regions. We used DNA polymorphisms to distinguish parental alleles in the mouse. Unexpectedly, DNA methylation was not observed in the Meg promoter regions of either the paternally repressed or maternally expressed alleles in kidney or brain tissues (Fig. 2, left). This suggests that maternal expression of Meg1/Grb10 is not correlated with the DNA methylation status of the Meg promoter region. In this respect, the human GRB10 was similar to the mouse Meg1/Grb10 gene. Although we could not distinguish parental alleles in this experiment, DNA methylation was not observed in the CpG islands of the human major promoter regions that showed biallelic expression (data not shown). Both the human and mouse CpG islands were 1.4 kb in length (Fig. 3A, middle left) and their sequences were highly conserved, as calculated using the program VISTA (http://www-gsd.lbl.gov/vista) (Fig. 3A, lower left), although the transcription start sites were similar, but not exactly the same (Fig. 3A, middle). Whether the slightly different locations of the first exons in these species cause the differences in imprinted expression profiles is currently unknown.

Figure 2.

DNA methylation status of two promoter regions in the mouse Meg1/Grb10 gene. Eight to ten clones from the paternal and maternal alleles were sequenced. DNA methylation was absent in both the paternal and maternal alleles of the Meg promoter region. In contrast, differential methylation (i.e. full methylation in paternal alleles and non-methylation in maternal alleles) was detected in the Peg promoter region. Differential methylation patterns were already established in the sperm and eggs. Parental alleles are distinguished by DNA polymorphisms between JF1 and B6. The black circles indicate methylated CpGs and the white circles indicate non-methylated CpGs.

In contrast, the Peg promoter regions in mice and humans were clearly differentially methylated between parental alleles (Fig. 2, right). The maternal alleles in the mouse were fully methylated and the paternal alleles were non-methylated, both in the kidney and brain samples (Fig. 2, right upper two grids). Importantly, differential methylation was already established in the oocytes and sperm; the former were fully methylated and the latter were non-methylated (Fig. 2, right lower two grids), which demonstrates that this is the primary differentially methylated region (DMR) that plays a potentially important role in the imprinting regulation of this gene. Similarly, 50% of the DNA sequences recovered from human samples were fully methylated and the other 50% were non-methylated both in the kidney and brain samples (data not shown). Although we could not distinguish parental alleles in the human samples, it is likely that this DMR also exists in the human gene.

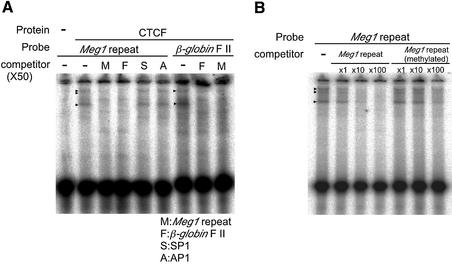

CTCF-binding activity in the mouse Peg promoter region

Although the CpG islands in the Peg promoter regions were highly conserved between the two species, they differed in length by ∼600 bp (Fig. 3A, left; 1.5 kb in the mouse and 0.9 kb in the human gene). Interestingly, we found GC-rich tandem repeats within this 600 bp sequence (Fig. 3B). Using the gel shift assay with whole cell extracts from kidney, brain and muscle samples and the 40 bp Meg1 repeat (Fig 3B, boxed) as the probe, we investigated whether a certain factor(s) bound to this region. Actually, some shifted bands were detected in all samples (data not shown). We considered CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor) to be a good candidate for the shifted bands because of its relatively broad binding specificity to GC-rich sequences (19,21,22). Then, we examined the direct binding of CTCF to the Meg1 repeat (Fig. 4A, left). The results clearly demonstrate that CTCF binds specifically to the 40 bp Meg1 repeat (second lane from the left). A canonical CTCF-binding sequence from chicken β-globin (FII) specifically competed CTCF binding to the Meg1 repeat (lane indicated by competitor F), although the recognition sequences for the SP1 and AP1 transcription factors did not interfere with CTCF binding (lanes indicated by competitors S and A). Conversely, the Meg1 repeat specifically inhibited the binding of CTCF to the FII sequence (Fig. 4A, right). Importantly, the fully methylated Meg1 repeat showed less competitive activity than the unmethylated sequence (Fig. 4B), which suggests that CTCF binding to the mouse Peg promoter region is DNA methylation sensitive. Therefore, the CTCF might function as a DNA methylation-sensitive insulator from some downstream enhancer(s) that controls expression from the upstream Meg promoter (Fig. 5). The remaining part of the mouse DMR region (upstream and downstream from the Meg1 repeat) and the corresponding regions of human DMR did not show apparent CTCF-specific binding using the same in vitro gel shift assays (data not shown).

Figure 4.

CTCF binds specifically to the Meg1 repeat. (A) Specific competition for CTCF binding to the Meg1 repeat was seen for the canonical CTCF- binding sequence of the chicken β-globin FII (as shown in F), but not for the transcription factor recognition sequences of SP1 and AP1 (as shown in S and A) and vice versa. Mouse recombinant CTCF containing a full-length coding sequence was used. There were no DNA-binding factors included in the in vitro reticulocyte transcription/translation reaction mixture without CTCF-containing vector (left most lane). (B) The methylated Meg1 repeat was a less effective competitor than the non-methylated sequence.

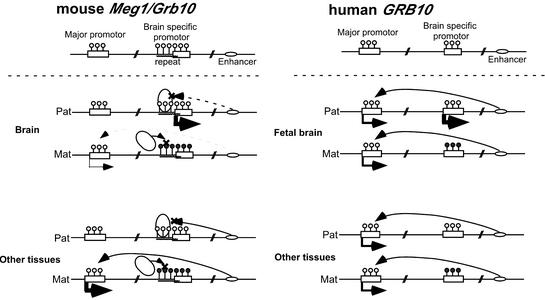

Figure 5.

Working models of tissue-specific expression regulation of the mouse Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10 genes. The mouse model with an insulator sequence (left) and the human model without an insulator sequence (right) are shown. White lollipops indicate the unmethylated CpG motifs and black lollipops indicate the methylated CpG motifs. The small ovals indicate putative downstream enhancers and the large ovals indicate CTCF. Big and small arrows correspond to the expression levels measured by RT–PCT, as shown in Figure 1B and C. In both the mouse and human models, we presuppose that paternal expression from Peg promoters is regulated by both DNA methylation and putative brain-specific activators (not drawn in these figures); therefore, paternal alleles in other tissues are not active due to the lack of activator and maternal alleles are inactivated by DNA methylation. In the non-methylated paternal allele in the mouse, the upstream Meg promoter is repressed because the insulator blocks the function of the downstream enhancer, whereas in methylated maternal alleles the major promoter is active, since there is no interference with the enhancer blocking effect of the insulator. However, maternal expression in the brain is low compared with expression in other tissues (shown with dashed lines). It is possible that the downstream enhancer acts in a somewhat tissue-specific manner and is weak in the brain. Therefore, it shows biallelic, but strong paternally biased, expression in the brain, and maternal expression in other tissues. In humans (right), both of the parental major promoters are active, since the insulator sequence is absent. Therefore, it shows biallelic, but strong paternally biased, expression in the fetal brain, and biallelic expression in other tissues.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that mouse Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10 each have two promoters with different imprinted expression profiles. It has been reported that some imprinted genes change their imprinted expression patterns during development or show different imprinted expression patterns in different organs and tissues. Igf2 shows paternal expression in embryos and some neonatal tissues and organs, but it is expressed biallelically in the choroid plexus of the adult brain (23). It has also been reported that Igf2 shows biallelic expression in the early embryonic stage when the P1 promoter is used, whereas imprinted paternal expression is usually observed in transcripts from the major P2 and P3 promoters (24–26).

Other examples of imprinted patterning include the mouse Peg1/Mest and human PEG1/MEST genes. The former shows almost exclusive paternal expression in both embryos and adult tissues, whereas in the latter case, <5% of the maternally derived transcripts are detected continuously in human embryos (27), and complete biallelic expression is observed in human blood (28). Recently, the existence of another promoter that modulates biallelic expression and that is located upstream of the previously known major promoter for paternal expression was reported (28,29). We have also reported that the maternal contribution of PEG1/MEST in embryos and blood is due to expression from the upstream promoter (30).

Three different imprinted genes on the mouse distal chromosome 2 show paternal (GnasXL), maternal (Nesp) or biparental (Gnas) expression profiles (31,32). Although these genes are transcribed from different promoters and encode proteins with different functions, they share some common exons. Therefore, these three different genes with different imprinting profiles represent alternative transcripts of the Gnas locus. All of these examples indicate that alternative usage of different promoters is one of the mechanisms for the differential expression profiles of imprinted genes.

Loss of imprinting (LOI) is another mechanism behind the changes in imprinted gene expression patterns (33,34). It is known that H19 and IGF2 show abnormal imprinted expression profiles in certain cancers and some Beckwith– Wiedeman syndrome patients (35,36). In these cases, changes in the imprinting patterns are associated with the DNA methylation patterns of the DMRs that control imprinting, and may also be associated with DNA mutations or small deletions in the imprinting control region. However, as far as we know, there is no direct evidence that LOI appears during normal development to regulate the expression of imprinted genes. Thus, it will be very important to examine the mechanisms of imprinted gene expression in cases where the expression profiles change during development, in cancers and in genetic diseases (24,28–30).

Comparisons of the regulatory mechanisms of mouse Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10 may provide support for the role of insulators in mediating secondary reciprocal imprinted expression of neighboring genes (Fig. 5), which was originally proposed from experiments that analyzed the Igf2–H19 region (37,38). In the case of Igf2–H19, DNA methylation-sensitive CTCF binding to the upstream region of H19 has an important function in providing insulation from downstream enhancer sequences. Thus, when the binding sites are non-methylated, CTCF binds and blocks enhancer activity, which induces repression of the upstream Igf2 gene. When the binding sites are methylated, CTCF cannot bind in a stable fashion and the lack of insulator function allows the expression of Igf2.

The regions between the promoters of Meg1/Grb10 and GRB10 are highly homologous between humans and mice, except for the 600 bp, mouse-specific tandem repeat region that contains the specific CTCF-binding sequence (Fig. 3). Binding of CTCF to the Meg1 repeat is both specific and DNA methylation sensitive (Fig. 4) and only this region shows CTCF binding activity within the mouse and human DMRs (data not shown). A precise recognition sequence for CTCF remains to be determined. However, a similar CTCF insulator could change paternal expression to maternal expression by switching (via DNA methylation) expression of the gene from the downstream Peg promoter to the upstream Meg promoter (Fig. 5). Our results suggest that the combination of promoter-specific methylation and DNA methylation-sensitive insulator sequences is a key regulatory mechanism through which the expression patterns of mouse Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10 are controlled differentially between organs and tissues, and between humans and mice. In these working models, we presuppose that brain-specific activation of Peg promoters is regulated by some brain-specific activator(s) (not drawn in these figures) binding to these regions, which is mechanically independent of the insulator function. Another presumed condition is that downstream enhancers show some tissue specificity and this is not as strong in the mouse brain as in other tissues, as indicated by dashed lines.

Another important mechanism is the alternative usage of two promoters showing different imprinted expression profiles, as mentioned above. It should also be noted that the paternal contribution in the mouse brain appears to increase during development. Therefore, the balance between the Peg promoter and Meg promoter may change during this process. It will be very important to identify factors involved in regulatory mechanisms, such as enhancer sequences and the putative brain-specific activator. It will also be important to show that insulator activity accounts for differential imprinting between humans and mice, by dissecting the functional units and reconstructing them to produce artificially imprinted chromosomal regions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Ko Ishihara and Hiroyuki Sasaki for providing the plasmid vector containing the mouse recombinant CTCF gene and for the chicken β-globin FII probe that was used in the gel shift assay. This work was supported by grants to F.I. from CREST, the research program of the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST), Asahi Glass Foundation and the Uehara Memorial Life Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miyoshi N., Kuroiwa,Y., Kohda,T., Shitara,H., Yonekawa,H., Kawabe,T., Hasegawa,H., Barton,S.C., Surani,M.A., Kaneko-Ishino,T. and Ishino,F. (1998) Identification of the Meg1/Grb10 imprinted gene on mouse proximal chromosome 11, a candidate for the Silver-Russell syndrome gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 1102–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai R.Y., Jahn,T., Schrem,S., Munzert,G., Weidner,K.M., Wang,J.Y. and Duyster,J. (1998) The SH2-containing adapter protein GRB10 interacts with BCR-ABL. Oncogene, 17, 941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill T.J., Rose,D.W., Pillay,T.S., Hotta,K., Olefsky,J.M. and Gustafson,T.A. (1996)) Interaction of a GRB-IR splice variant (a human GRB10 homolog) with the insulin and insulin-like growth factor I receptors. Evidence for a role in mitogenic signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22506–22513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrione A., Valentinis,B., Resnicoff,M., Xu,S. and Baserga,R. (1997) The role of mGrb10alpha in insulin-like growth factor I-mediated growth. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 26382–26387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu F. and Roth,R.A. (1998) Binding of SH2 containing proteins to the insulin receptor: a new way for modulating insulin signalling. Mol. Cell. Biochem., 182, 73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moutoussamy S., Renaudie,F., Lago,F., Kelly,P.A. and Finidori,J. (1998) Grb10 identified as a potential regulator of growth hormone (GH) signaling by cloning of GH receptor target proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 15906–15912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattanach B.M., Shibata,H., Hayashizaki,Y., Townsend,K.M., Ball,S. and Beechey,C.V. (1998) Association of a redefined proximal mouse chromosome 11 imprinting region and U2afbp-rs/U2af1-rs1 expression. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 80, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerome C.A., Scherer,S.W., Tsui,L.C., Gietz,R.D. and Triggs-Raine,B. (1997) Assignment of growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 (GRB10) to human chromosome 7p11.2-p12. Genomics, 40, 215–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spotila L.D., Sereda,L. and Prockop,D.J. (1992) Partial isodisomy for maternal chromosome 7 and short stature in an individual with a mutation at the COL1A2 locus. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 51, 1396–1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotzot D., Schmitt,S., Bernasconi,F., Robinson,W.P., Lurie,I.W., Ilyina,H., Mehes,K., Hamel,B.C., Otten,B.J., Hergersberg,M. et al. (1995) Uniparental disomy 7 in Silver-Russell syndrome and primordial growth retardation. Hum. Mol. Genet., 4, 583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce C.A., Sharp,A., Walker,J.M., Bullman,H. and Temple,I.K. (1999) Duplication of 7p12.1-p13, including GRB10 and IGFBP1, in a mother and daughter with features of Silver-Russell syndrome. Hum. Genet., 105, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk D., Wakeling,E.L., Proud,V., Hitchins,M., Abu-Amero,S.N., Stanier,P., Preece,M.A. and Moore,G.E. (2000) Duplication of 7p11.2-p13, including GRB10, in Silver-Russell syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 66, 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hitchins M.P., Monk,D., Bell,G.M., Ali,Z., Preece,M.A., Stanier,P. and Moore,G.E. (2001) Maternal repression of the human GRB10 gene in the developing central nervous system; evaluation of the role for GRB10 in Silver-Russell syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 9, 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blagitko N., Mergenthaler,S., Schulz,U., Wollmann,H.A., Craigen,W., Eggermann,T., Ropers,H.H. and Kalscheuer,V.M. (2000) Human GRB10 is imprinted and expressed from the paternal and maternal allele in a highly tissue- and isoform-specific fashion. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 1587–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hitchins M.P., Bentley,L., Monk,D., Beechey,C., Peters,J., Kelsey,G., Ishino,F., Preece,M.A., Stanier,P. and Moore,G.E. (2002) DDC and COBL, flanking the imprinted GRB10 gene on 7p12, are biallelically expressed. Mamm. Genome, 12, 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko-Ishino T., Kuroiwa,Y., Miyoshi,N., Kohda,T., Suzuki,R., Yokoyama,M., Viville,S., Barton,S.C., Ishino,F. and Surani,M.A. (1995) Peg1/Mest imprinted gene on chromosome 6 identified by cDNA subtraction hybridization. Nature Genet., 11, 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raizis A.M., Schmitt,F. and Jost,J.P. (1995) A bisulfite method of 5-methylcytosine mapping that minimizes template degradation. Anal. Biochem., 226, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manley J.L., Fire,A., Cano,A., Sharp,P.A. and Gefter,M.L. (1980) DNA-dependent transcription of adenovirus genes in a soluble whole-cell extract. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 3855–3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihara K. and Sasaki,H. (2002) An evolutionarily conserved putative insulator element near the 3′ boundary of the imprinted Igf2/H19 domain. Hum. Mol. Genet., 11, 1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagase T., Seki,N., Ishikawa,K., Ohira,M., Kawarabayasi,Y., Ohara,O., Tanaka,A., Kotani,H., Miyajima,N. and Nomura,N. (1996) Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. VI. The coding sequences of 80 new genes (KIAA0201-KIAA0280) deduced by analysis of cDNA clones from cell line KG-1 and brain. DNA Res., 3, 321–329, 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobanenkov V.V., Nicolas,R.H., Adler,V.V., Paterson,H., Klenova,E.M., Polotskaja,A.V. and Goodwin,G.H. (1990) A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′-flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene, 5, 1743–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohlsson R., Renkawitz,R. and Lobanenkov,V. (2001) CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet., 17, 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeChiara T.M., Robertson,E.J. and Efstratiadis,A. (1991) Parental imprinting of the mouse insulin-like growth factor II gene. Cell, 64, 849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vu T.H. and Hoffman,A.R. (1994) Promoter-specific imprinting of the human insulin-like growth factor-II gene. Nature, 371, 714–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlsson R., Hedborg,F., Holmgren,L., Walsh,C. and Ekstrom,T.J. (1994) Overlapping patterns of IGF2 and H19 expression during human development: biallelic IGF2 expression correlates with a lack of H19 expression. Development, 120, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feil R., Handel,M.A., Allen,N.D. and Reik,W. (1995) Chromatin structure and imprinting: developmental control of DNase-I sensitivity in the mouse insulin-like growth factor 2 gene. Dev. Genet., 17, 240–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi S., Kohda,T., Miyoshi,N., Kuroiwa,Y., Aisaka,K., Tsutsumi,O., Kaneko-Ishino,T. and Ishino,F. (1997) Human PEG1/MEST, an imprinted gene on chromosome 7. Hum. Mol. Genet., 6, 781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosaki K., Kosaki,R., Craigen,W.J. and Matsuo,N. (2000) Isoform-specific imprinting of the human PEG1/MEST gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 66, 309–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen I.S., Dervan,P., McGoldrick,A., Harrison,M., Ponchel,F., Speirs,V., Isaacs,J.D., Gorey,T. and McCann,A. (2002) Promoter switch: a novel mechanism causing biallelic PEG1/MEST expression in invasive breast cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet., 11, 1449–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi S., Uemura,H., Kohda,T., Nagai,T., Chinen,Y., Naritomi,K., Kinoshita,E.I., Ohashi,H., Imaizumi,K., Tsukahara,M. et al. (2001) No evidence of PEG1/MEST gene mutations in Silver-Russell syndrome patients. Am. J. Med. Genet., 104, 225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters J., Wroe,S.F., Wells,C.A., Miller,H.J., Bodle,D., Beechey,C.V., Williamson,C.M. and Kelsey,G. (1999) A cluster of oppositely imprinted transcripts at the Gnas locus in the distal imprinting region of mouse chromosome 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3830–3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattanach B.M., Peters,J., Ball,S. and Rasberry,C. (2000) Two imprinted gene mutations: three phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 2263–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rainier S., Johnson,L.A., Dobry,C.J., Ping,A.J., Grundy,P.E. and Feinberg,A.P. (1993) Relaxation of imprinted genes in human cancer. Nature, 362, 747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogawa O., Eccles,M.R., Szeto,J., McNoe,L.A., Yun,K., Maw,M.A., Smith,P.J. and Reeve,A.E. (1993) Relaxation of insulin-like growth factor II gene imprinting implicated in Wilms’ tumour. Nature, 362, 749–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reik W. and Walter,J. (2001) Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki H., Ishihara,K. and Kato,R. (2000) Mechanisms of Igf2/H19 imprinting: DNA methylation, chromatin and long-distance gene regulation. J. Biochem. (Tokyo), 127, 711–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hark A.T., Schoenherr,C.J., Katz,D.J., Ingram,R.S., Levorse,J.M. and Tilghman,S.M. (2000) CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature, 405, 486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell A.C. and Felsenfeld,G. (2000) Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature, 405, 482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.