Abstract

Integrin receptor signals are costimulatory for mitogenesis with the T-cell receptor during T-cell activation. A subset of integrin receptors can link to the adapter protein Shc and provide a mitogenic stimulus. Using a combination of genetic and pharmacological approaches, we show herein that integrin signaling to Shc in T cells requires the receptor tyrosine phosphatase CD45, the Src family kinase member Lck, and protein kinase C. Our results suggest a model in which integrin-dependent serine phosphorylation of Lck is the critical step that determines the efficiency of Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells. Serine phosphorylation of Lck is dependent on PKC and is also linked to CD45 dephosphorylation. Mutants of Lck that cannot be phosphorylated on the critical serine residues do not signal efficiently to Shc and have greatly reduced kinase activity. This signaling from integrins to Lck may be an important step in the costimulation with the T-cell receptor during lymphocyte activation.

INTRODUCTION

Integrins are a family of heterodimeric (αβ) receptors that mediate interactions among cells and between cells and extracellular matrix (Hynes, 1992; Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999). Like all other cell surface receptors, integrins require ligand binding for the elucidation of downstream signaling events. This phenomenon has been termed “outside-in” information flow, to distinguish it from the activation of integrin ligand binding via other cell surface receptors and intracellular signaling pathways or so called “inside-out” signaling. The outside-in signals transmitted by integrins are essential for cell migration, development, and differentiation. In the immune system, integrin receptors play important roles in T-cell development (Schmeissner et al., 2001) and in migration and adhesion in normal function (Shimizu et al., 1990; Kellermann et al., 2002). In addition, it is now apparent that integrins play a critical role in the organization of the so-called T-cell or immunological synapse, a critical assembly of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and other signaling molecules (Sims and Dustin, 2002).

It is now apparent that many of the integrin growth signals transmitted in cells are dependent on the activity of Src family tyrosine kinases (Klinghoffer et al., 1999). One of these signals transmitted into cells after integrin-ligand binding or antibody-mediated clustering is the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc, an Src homology (SH)2-phosphotyrosine-binding adapter protein that can relay receptor tyrosine phosphorylation signals to Ras by recruiting the Grb2/SOS complex to the cell membrane (Pawson and Scott, 1997). Integrin-Shc signaling has been shown to be crucial for promoting the transition through G1 phase of cell cycle in adherent cells. Adhesion mediated by integrins not linked to Shc results in cell cycle arrest even in the presence of mitogens (Mainiero et al., 1995; Wary et al., 1996; Mainiero et al., 1997). Using a variety of adherent cells, it has been demonstrated that caveolin-1 can physically and functionally couple integrins to the Src family tyrosine kinase Fyn. Ligand binding or antibody-mediated cross-linking of integrins can activate Fyn, which in turn binds Shc via its SH3 domain, and phosphorylates it (Wary et al., 1998).

It is clear that a key step in the regulation of integrin-Shc signals in fibroblasts is activation of the tyrosine kinase Fyn. As is the case with all Src kinase family members, Fyn contains a unique N-terminal region: two regulatory domains (SH2 and SH3) and a large C-terminal catalytic domain with conserved regulatory tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Thomas and Brugge, 1997). The catalytic activity of Src kinases is regulated by intramolecular interactions. The crystal structures of inactive Hck and Src support this idea, because these structures show that both SH2 and SH3 domain of the protein repress the kinase activity by interacting with the catalytic domain and surrounding amino acids (Sicheri et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1997, 1999). There are multiple potential ways to disrupt this intramolecular interaction and activate Src kinases, one of which is to dephosphorylate the negative regulatory tyrosine residue located near the carboxy terminus, which is bound by the SH2 domain (Thomas and Brugge, 1997). Because Fyn is activated by integrin ligand binding or antibody cross-linking in adherent cells, we reasoned that integrin ligation could either activate a tyrosine phosphatase or make it accessible to Fyn. This putative tyrosine phosphatase would most likely be membrane bound. In adherent cells, there are data to suggest that the receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase α and the cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 can regulate integrin-dependent Src family kinase activation (Oh et al., 1999; Su et al., 1999).

In hematopoietic cells, one candidate for such a membrane tyrosine phosphatase that can potentially activate Src family members kinase activity is CD45, a leukocyte cell-specific transmembrane glycoprotein with a tandem repeat of protein tyrosine phosphatase domains in its cytoplasmic region (Ralph et al., 1987). The function of CD45 in antigen receptor signaling has been studied extensively. It regulates pre-TCR and TCR complex-mediated signal transduction during T-cell development (Byth et al., 1996). CD45-deficient human T-cell lines are defective in their ability to respond to signals via their TCR–CD3 complex (Koretzky et al., 1991; Shiroo et al., 1992), and this signaling can be restored by reconstitution of functional CD45 (Koretzky et al., 1990, 1992; Desai et al., 1993; Hovis et al., 1993; Volarevic et al., 1993). CD45 has been shown to regulate both the Src family kinases Lck and Fyn. For example, CD45 has been found to be colocalized selectively with Fyn in functional human T lymphocytes. It can dephosphorylate the negative regulatory tyrosine within the carboxy terminus of both Fyn and Lck. In a CD45-deficient T-lymphocyte clone (L3), tyrosine phosphorylation of a Fyn C-terminal peptide, which contains the negative regulatory tyrosine, is increased twofold (Cahir McFarland et al., 1993).

Although the role of Fyn in integrin-Shc signaling in adherent fibroblasts is well established, it remains unclear whether Fyn is the only Src family kinase that participates in this signaling process in T cells. In addition to Fyn, T cells express another Src family kinase, Lck. Fyn and Lck share striking overall sequence similarity. Both proteins are myristylated and palmitylated and are expressed abundantly in mature T cells. Both kinases are important in TCR αβ/CD3-mediated signal transduction in mature T cells, in which Shc tyrosine phosphorylation is also important (Weiss and Littman, 1994; Anderson and Perlmutter, 1995). Furthermore, it has demonstrated that Lck/CD4 cross-linking can result in the phosphorylation of Shc Tyr 317 in a murine T-cell line, which is the same position kinased by Fyn in fibroblasts, and represents a binding site for the SH2 domain of Grb2 (Wary et al., 1996, 1998; Walk et al., 1998). We therefore wondered whether Fyn and Lck could play redundant roles in integrin-Shc signaling in T cells.

In the present study, we have taken the advantage of availability of CD45-deficient and CD45-reconstituted Jurkat cell lines and tested the hypothesis that CD45, or a CD45-like transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase, depending on the cell type, participates in integrin-Shc signaling. We found that CD45 was indeed required for β1 integrin-mediated Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. In addition, we have investigated whether Lck takes a part in this signaling event. We found that CD45 regulates Lck kinase activity in Jurkat cells and that Lck kinase activity is required for integrin-mediated Shc phosphorylation. Integrin clustering led to serine phosphorylation of Lck, and this modification is protein kinase C (PKC) dependent. In addition, efficient phosphorylation of Shc in response to integrin clustering in T cells also requires PKC activity. Most strikingly, mutants of Lck with alanine substitution of critical serine residues were profoundly deficient in Shc phosphorylation and kinase activity, showing that these sites are essential for integrin-Shc signaling in T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Cell Lines

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 4B4 (anti-β1) and 3A5 (anti-Lck) were purchased from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, CA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Cells producing mAb GAP8.3 (anti-CD45) were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Polyclonal anti-human focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Shc antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). RC-20-H (peroxidase-conjugated recombinant anti-P-Tyr PY 20) was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Polyclonal anti-phospho-Src family Tyr 416 antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Leukemic T-cell lines Jurkat, J45.01 (CD45-deficient Jurkat), and Jcam 1.6 (Lck-deficient Jurkat) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Dr. G. Koretzky (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) provided J45/CH11 (transfectant of J45.01 that express A2/CD45 chimeric molecule) and J45LB3 (transfectant of J45.01 that express full-length CD45). Jurkat, J45.01, and Jcam 1.6 were routinely maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml). J45/CH11 and J45LB3 were maintained in above-mentioned medium supplemented additionally with G418 (2 mg/ml).

A G418-resistant Jcam1 cell line, which expresses a VP16-tetracycline repressor fusion protein, was provided by Dr. D. Straus (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA) (Denny et al., 2000). The Lck S42A, S59A, S42AS59A, S42E, S59E, and S42ES59E mutants were generated from wild-type (Wt) mouse Lck cDNA by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and were confirmed by sequencing. These cDNAs were subcloned into the pBP1 vector that contains a cytomegalovirus promoter sequence regulated by tetracycline operators, and a gene conferring resistance to the antibiotic hygromycin (Denny et al., 2000). These vectors were transfected into JcaM1/tetra-VP16 cells by electroporation (250 V and 960 μF) by using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) apparatus. Stable cell lines were selected using hygromycin resistance and screened by Western blotting. Stable clones that express Lck at levels similar to the parental Jurkat cell line were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml) with 2 mg/ml G418 and 300 μg/ml hygromycin B.

Biochemical Methods

To obtain cross-linking of β1 integrins, ∼107 cells were collected and resuspended in serum-free medium (150 μl). Suspended cells were then incubated at 37°C for 15 min with either 4B4-conjugated or -unconjugated polystyrene beads. Antibody coating of the beads was carried out by incubating 5 × 109 surfactant-free sulfate white polystyrene latex beads (2.4 μm in diameter; Interfacial Dynamics, Portland, OR) with 100 μg of 4B4 in 300 μl of conjugation buffer (30 mM Na2CO3, 70 mM NaHCO3, pH 9.5) for 1.5 h at room temperature. At the end of cross-linking, cells were extracted on ice for 30 min with 1 ml of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM pyrophosphate, and 2 mM Na3VO4, pH 7.5) supplemented with 10 μl/ml mammalian cell protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

For immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of Shc, Lck, and FAK, total cell extracts were incubated in lysis buffer with 50 μl of GammaBind G Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and either 10 μg of polyclonal anti-human Shc or FAK or 5 μg of monoclonal anti-human Lck for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (for Shc, Lck, or FAK antibodies) or 5% bovine serum albumin (for RC-20). Nitrocellulose-bound antibodies were detected by chemiluminescence with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

For immune complex autokinase assays, complexes were recovered from extracts prepared with a modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer 1 (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 10% glycerol). These immune complexes were washed three times with buffer 1, twice with buffer 2 (0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol), and twice with buffer 3 (20 mM Tris pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2). After the washes, immune complexes were incubated in 30 μl of buffer 3 supplemented with 20 μM cold ATP and 10 μCi of [32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) for 2 min at 30°C. Washing the immune complexes with buffer 3 twice, followed by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer stopped the reaction. After SDS-PAGE, gels were fixed (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid for 30 min, and then 10% methanol, 10% acetic acid for 30 min) and then incubated in 1 M KOH for 2 h at 56°C to hydrolyze phosphates on serine/threonine residues. Finally, gels were rinsed in 10% acetic acid and 10% methanol for 20 min and in 10% acetic acid and 50% methanol for 20 min before being dried for autoradiography. Quantification of scanned films was performed using NIH Image software.

For CD45 immune complex phosphatase assays, 107 Jurkat cells were lysed in 1 ml of 1% Triton, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol for 0.5 h at 4°C. The total cell lysate was then incubated in the lysis buffer with 50 μl of goat anti-mouse Sepharose and 250 μl of supernatant of GAP 8.3 culture medium for 2 h at 4°C. At the end of incubation, Sepharose was washed four times with lysis buffer followed by another four times wash with phosphatase assay buffer (0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, pH 6.0). The beads were incubated in 20 μl of assay buffer with 5 μl of a phosphotyrosine peptide provided in a tyrosine phosphatase assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology) for 10 min. The assay was stopped by addition of 100 μl of Malachite Green solution and free phosphate was measured by absorbance reading at 620 nm.

Flow Cytometry

Flourescence flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACScan fluorocytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Harvested cells were washed three times with PCN (phosphate-buffered saline, 0.5% calf serum, and 0.5% NaN3). Cells were stained with primary antibodies on ice for 30 min, followed by three washes with cold PCN. Cells were then resuspended and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies in PCN for 30 min on ice. After three washes with PCN, cells were fixed in phosphate-buffered saline plus 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed.

RESULTS

A Requirement for CD45 in Integrin Shc Signaling in Jurkat Cells

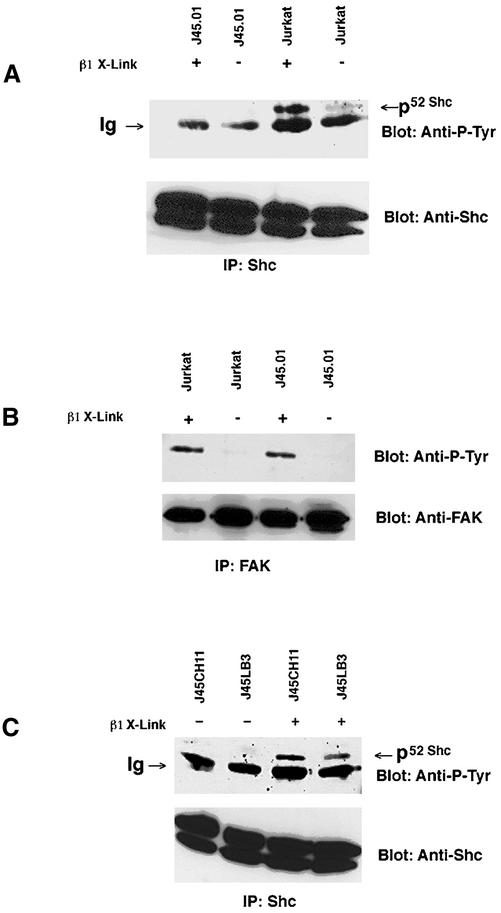

To address the role of CD45 in β1 integrin-mediated Shc tyrosine phosphorylation, we compared the integrin signaling in two cell lines, a T-cell leukemia line, Jurkat; and a CD45-deficient Jurkat clone, J45.01 (Koretzky et al., 1991). It was previously demonstrated that antibody-mediated clustering of β1 integrins could lead to tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc in Jurkat cells (Wary et al., 1996). We cross-linked β1 integrins on Jurkat by incubating the cells with beads coated with the anti-β1 integrin mAb, 4B4. The adapter protein Shc was then immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-human Shc antibody and subjected to immunoblotting with both the anti-Shc antibodies and anti-phosphotyrosine (RC-20). As shown in Figure 1A, the 52-kDa isoform of Shc was tyrosine phosphorylated after the antibody-mediated β1 integrin clustering. We then examined the effect of β1 integrin clustering on Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in J45.01 cells. As demonstrated in Figure 1A, although Shc in Jurkat cells was tyrosine phosphorylated after antibody mediated cross-linking, no phosphorylated Shc was observed in J45.01 cells under the same conditions.

Figure 1.

Integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation in Jurkat cells: requirement for CD45. (A) Wild-type Jurkat cells were compared with CD45-deficient Jurkat cells (J45.01). Cells (107) for each cell line were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-Shc antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-P-Tyr (RC-20) and visualized by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Shc and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Arrow points to the position of the 52-kDa isoform of Shc. The band below, which is present in all lanes, is related to the polyclonal anti-Shc, because it remains present even in the absence of cell extracts (our unpublished data). Note the cross-linking–dependent phosphorylation of Shc in Jurkat, but in the CD45-deficient cell line J45.01. (B) FAK phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. Wild-type Jurkat cells were compared with CD45-dependent Jurkat cells (J45.01). Cells (107) for each cell line were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-FAK antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-P-Tyr (RC-20) and visualized by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-FAK and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Note the cross-linking–dependent phosphorylation of FAK in both cell lines, demonstrating that FAK phosphorylation does not require CD45 and that β1 cross-linking in J45.01 is effective. (C) Integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation: requirement of the presence of CD45 phosphatase. CD45 cDNA (J45LB3) or a chimera consisting of the extracellular domain of HLA A2 connected to the intracellular domain of CD45 (J45CH11) was expressed in previously CD45-deficient J45.01 cells. Cells (107) for each line were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-Shc antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-P-Tyr (RC-20) and visualized by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Shc and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Note the cross-linking–dependent phosphorylation of Shc is restored with both CD45 (J45LB3) and with the chimeric molecule (J45CH11).

We performed a number of control experiments to verify that these differences were due to the lack of CD45. First, we examined by flow cytometry the integrin repertoire and expression level of J45.01 and Jurkat cells and found them to be very similar (our unpublished data). Moreover, to address whether there was a defect in the J45.01 cells' abilities to respond to the antibody-mediated β1 integrin clustering and whether there was a global need of CD45 for all the signaling processes initiated by integrin cross-linking, we examined the tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK. As shown in Figure 1B, clustering of β1 integrins on Jurkat and J45.01 cells led to similar levels of FAK tyrosine phosphorylation in both cell lines, indicating there was specific requirement of CD45 for integrin-Shc signaling and that the clustering of β1 integrins was equally effective in both cell lines.

Last, to ensure that CD45 deficiency is responsible for the lack of integrin-mediated Shc signaling in J45.01 cells, we used two stable CD45 transfectants of J45.01, J45LB3 (Koretzky et al., 1992) and J45CH11 (Hovis et al., 1993). J45LB3 cells have been reconstituted by expression of the full-length CD45 cDNA and J45CH11 cells express a chimera containing the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the HLA-A2 allele of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule and the entire cytoplasmic domain of CD45. We examined the effect of β1 integrin clustering on the Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in J45 LB3 and J45CH11 cells. In both cases, the reintroduced functional CD45 phosphatase rescued the Shc tyrosine phosphorylation observed in Jurkat cells (Figure 1C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CD45 tyrosine phosphatase activity is required for β1 integrin-mediated signaling to Shc in Jurkat cells.

Regulation of Fyn and Lck Kinase Activity by CD45

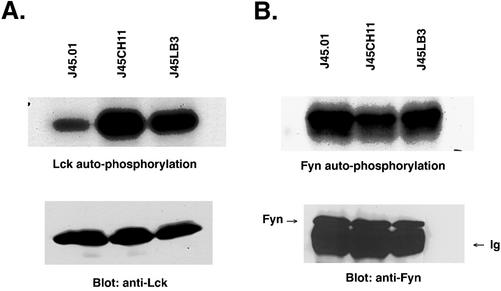

We next decided to examine the role of CD45 in integrin-mediated Shc signals in Jurkat cells. Because the tyrosine kinase Fyn is required for integrin signaling to Shc in adherent fibroblasts, one possible reason for the CD45 requirement would be to activate Fyn. To test this hypothesis, we immunoprecipitated Fyn from J45.01, J45LB3, and J45CH11 cells and performed autokinase assays of the Fyn immune complexes. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found in Fyn kinase activity among the three cell lines (Figure 2B). Because the primary difference among J45.01, J45LB3, and J45CH11 is that the latter two contain reconstituted functional CD45, this result indicates that under these conditions, Fyn catalytic activity is not significantly affected by CD45 activity in these cells.

Figure 2.

(A) Determination of Lck activity via autophosphorylation in Jurkat cell lines. CD45 cDNA (J45LB3) or a chimera consisting of the extracellular domain of HLA A2 connected to the intracellular domain of CD45 (J45CH11) was expressed in previously CD45-deficient J45.01 cells. Extracts of 107 cells of each of the three lines were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-Lck, followed by incubation in [32P]ATP in kinase buffer for 2 min at 30°C and then washed and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were soaked in KOH for 2 h at 65°C and then dried before autoradiography. Extracts of same number of each of the three lines also were immunoprecipitated with Lck antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse light chain antibodies, and visualized by ECL. Note the restored activity in both cell lines with CD45 (J45LB3) and with the chimera molecule (J45CH11). (B) Lack of regulation of Fyn kinase activity by CD45 phosphatase. J45LB3, J45CH11, or J45.01 cells were used. Extracts of 107 cells of each of the three lines were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Fyn, followed by incubation in [32P]ATP in kinase buffer for 2 min at 30°C, and then washed and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were soaked in KOH and then dried before autoradiography. Extracts of same number of each of the three lines also were immunoprecipitated with Fyn antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with polyclonal Fyn antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated protein A and visualized by ECL. Note the very similar levels of kinase activity in all cell lines, in contrast to Lck.

In addition to Fyn, CD45 also has been reported to be a regulator of Lck kinase activity in T cells. Likewise, if Lck participates in integrin-Shc signaling in Jurkat cells, one expects that Lck kinase activity would be regulated by CD45 in the cells. To test this hypothesis, the kinase activity of Lck immune complexes from J45.01, J45LB3, and J45CH11 was measured. As shown in Figure 2A, the catalytic activity of Lck from J45LB3 and J45CH11 was markedly higher than that from J45.01. This result clearly indicates that CD45 can positively regulate Lck activity in Jurkat cells. Furthermore, this result also suggests that Lck activity is required for integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation.

Lck Requirement for Integrin-mediated Shc Tyrosine Phosphorylation

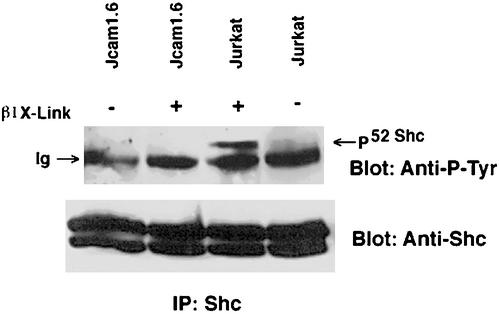

Because CD45 is required for integrin-linked Shc signaling and is regulating the kinase activity of Lck, the hypothesis can be put forth that Lck is involved in the phosphorylation of Shc upon integrin cross-linking. To test this further, we determine the amount of integrin-mediated Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in Jcam 1.6 cells. These cells, which were isolated by chemical mutagenesis of Jurkat cells, lack Lck kinase activity due to defective splicing of exon 7, which codes for the putative ATP binding site of the kinase (Straus and Weiss, 1992). TCR-mediated signaling events such as induction of inositol phosphates and intracellular calcium after TCR stimulation are deficient in this cell line, however, this signaling can be rescued by reconstitution of Lck activity into the cells, suggesting that other components of the signal transduction machinery are intact (Goldsmith and Weiss, 1987; Straus and Weiss, 1992). Thus, if Shc tyrosine phosphorylation after β1 integrin clustering in Jcam1.6 is normal then we could conclude that Fyn is sufficient, as has been shown in embryo fibroblasts (Wary et al., 1998). On the other hand, if Lck is required in the signaling process, one would expect a defect in Shc-tyrosine phosphorylation after integrin cross-linking in these cells. Therefore, we compared Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in Jurkat and Jcam 1.6 cells after antibody-mediated β1 integrin clustering. The results show that Shc phosphorylation is indeed defective in Jcam 1.6 cells after cross-linking (Figure 3). This result demonstrates the requirement of Lck for β1 integrin Shc signaling in Jurkat cells.

Figure 3.

Requirement of Lck for integrin-dependent phosphorylation of Shc. Wild-type Jurkat cells were compared with Lck-deficient Jurkat (Jcam 1.6). Cells (107) for each cell line were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-Shc antibodies and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose blots were stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-P-Tyr (RC-20) and visualize by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Shc and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Note the cross-linking–dependent phosphorylation of Shc in Jurkat, but not in the Lck-deficient cell line Jcam 1.6.

Effect of β1 Integrins Clustering on Fyn and Lck Kinase Activity

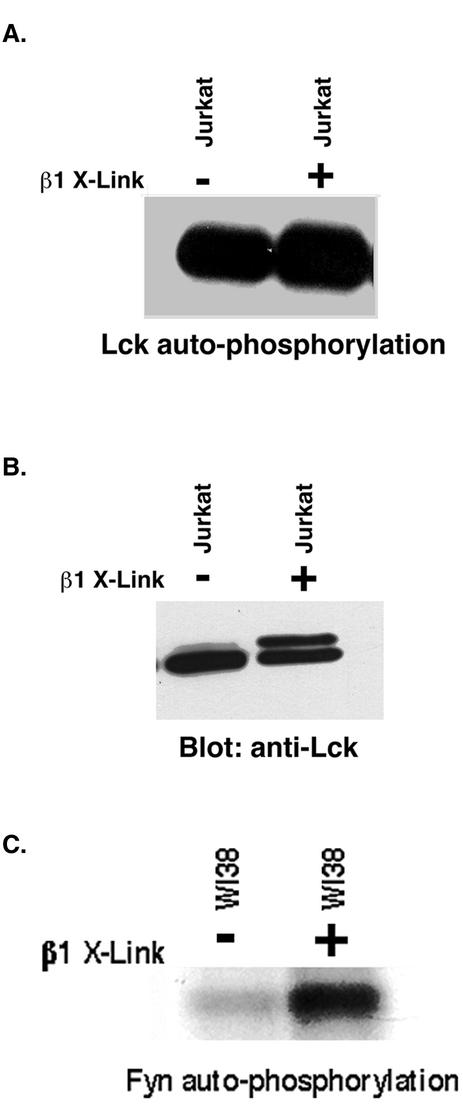

We next decided to investigate whether the clustering of integrins could regulate the activity of the Src family kinases Fyn or Lck in Jurkat cells. Others (Wary et al., 1998) have shown that kinase activity of Fyn was increased in fibroblasts after antibody-mediated β1 integrin cross-linking. Therefore, we determined the kinase activity of Fyn from β1 integrin cross-linked and noncross-linked Jurkat cells by using immune complex assays. No obvious difference was observed (our unpublished data). Furthermore, when we tested the kinase activity of Lck from β1 integrin-clustered and -unclustered Jurkat cells, again, we did not see any significant change (Figure 4A). This result may be due to the high level of Lck kinase activity observed before cross-linking. In fibroblasts, using anti-β1 antibody beads, we did see a significant activation of Fyn kinase activity by using the same assay conditions as shown above (Figure 4C). However, these cells have a much lower level of kinase activity before clustering. As a control for loading the same amount of enzyme in the autokinase assays, we split the immunoprecipitates and probed Western blots with Lck antibody to determine the amount of protein recovered. We noticed that upon clustering of integrins, the Lck band became two bands, with a rapid change in the electrophoretic mobility of the protein (Figure 4B). We decided to investigate this phenomenon further.

Figure 4.

Lack of stimulation of Lck activity by antibody-mediated β1 integrin clustering. Cells (107) were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated using monoclonal anti-Lck antibodies. Half the immune complex from each treatment was incubated in [32P]ATP in kinase buffer for 2 min at 30°C and then washed and separated by SDS-PAGE (A). The gels were soaked in KOH and then dried before autoradiography. The other half of the immune complex from each treatment was separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse light chain antibodies and visualized by ECL (B). Note there is no significant change in the kinase activity after cross-linking, but the mobility of a portion of the Lck is slower. (C) Fyn activation by integrin cross-linking in WI 38 cells. WI 38 cells were cross-linked in suspension for 10 min with beads coated either with or without anti-β1 antibodies. Lysates (600 μg) from each treatment were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Fyn antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and subjected to kinase assay. The gel was treated with 1 M NaOH at 56°C for 2 h before autoradiography.

Change in Gel Mobility of Lck Induced by β1 Integrin Cross-Linking

It has been reported that serine phosphorylation of the N-terminal unique region of Lck and the accompanying gel retardation (from 56–63 kDa) can occur upon treatment of T cells with phorbol ester, interleukin 2, and CD4/TCR cross-linking agents (Casnellie and Lamberts, 1986; Veillette et al., 1988; Einspahr et al., 1990; Horak et al., 1991). Ser 42 and Ser 59 in the N-terminal unique region of Lck have been identified as the major phorbol ester-induced phosphorylation sites. Phosphorylation of Ser 59 is responsible for the shift from 56 to 61 kDa, whereas phosphorylation of Ser 42 is required for the shift from 61 to 63 kDa. It has been found in vitro that mitogen-activated kinase and PKC or protein kinase A (PKA) could be responsible for the phosphorylation of Ser 59 and Ser 42, respectively (Winkler et al., 1993).

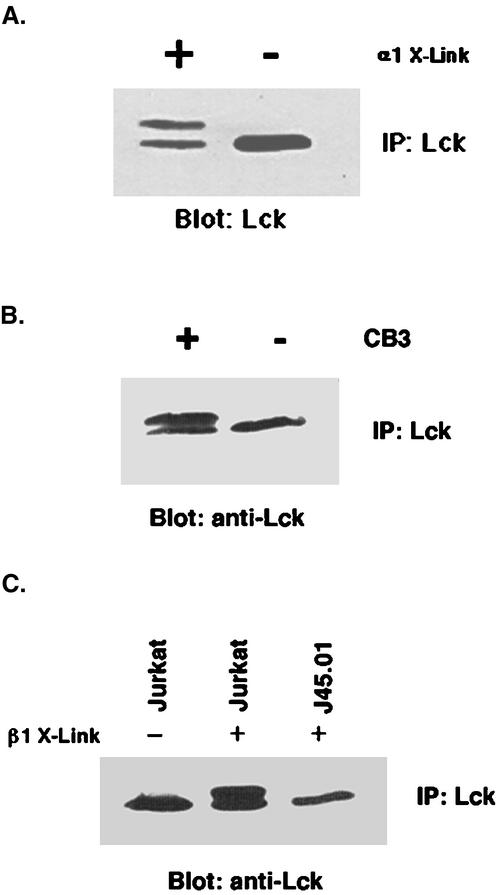

We decided to investigate this phosphorylation and gel retardation of Lck, induced upon integrin clustering, to determine whether this process played a role in the integrin-Shc signaling pathway. Our first step was to determine whether this shift occurs both with antibody-induced clustering and with authentic integrin ligands. Because flow cytometry measurements (our unpublished data) had determined that one of the β1 integrin heterodimers on the surface of Jurkat cells is α1β1, we decided to use antibodies and ligand for this integrin. To this end, we compared the electrophoretic mobility of Lck in untreated Jurkat cells with those treated with beads coated with TS2/7, an anti-human integrin α1 antibody, and with cells treated with beads coated with CB3, the cell binding fragment of collagen IV, a ligand for α1β1 (Kern et al., 1994). As shown in Figure 5, A and B, both treatments resulted in a mobility shift of a significant portion of the Lck. We next hypothesized that these phosphorylations may be relevant to Lck regulation if they were dependent on the presence of active CD45, because the carboxyl-terminal phosphotyrosine binding intramolecularly to the SH2 domain might prevent access to the amino terminus, where the modifications of Lck are likely to be occurring. Therefore, we clustered integrins on CD45 null J45.01 cells or on Jurkat cells. Strikingly, as shown in Figure 5C, Jurkat cells are able to generate the electrophoretic mobility shift upon integrin clustering, whereas the CD45 null cells cannot, which indicates that this shift requires CD45. These results suggest that the cleavage of the carboxyl-terminal P-Tyr is linked to the serine phosphorylation of the amino terminus.

Figure 5.

Modification of Lck electrophoretic mobility upon integrin cross-linking. (A) Jurkat cells (107) were either clustered with anti-α1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. (B) Jurkat cells (107) were either clustered with the cell binding fragment CB3 of collagen IV-coated beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. (C) Jurkat or J45.01 cells (107) were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody beads (+) or left unclustered (−) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Note the requirement of CD45 for the integrin-dependent modification of Lck. In all cases, extracts were immunoprecipitated using monoclonal anti-Lck antibodies. The immune complexes from each treatment were separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose the blot was stained with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse light chain antibodies and visualized by ECL. Note the shift in mobility of the Lck upon cross-linking.

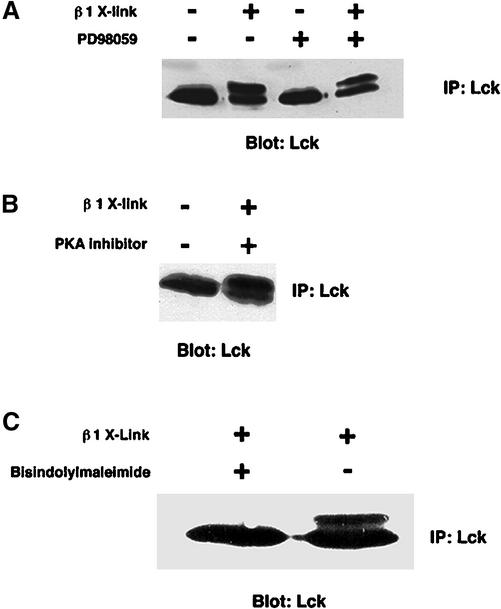

We next determined which protein kinase inhibitors could block this process. Figure 6, A–C, shows that neither mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) nor PKA inhibitors could prevent the change in electrophoretic mobility despite the fact that these two classes of kinases had been implicated in vitro in this mobility shift (Winkler et al., 1993). In contrast, PKC inhibitors, such as bisindolylmaleimide (Figure 6C) or staurosporine (our unpublished data), completely abolished the shift induced by integrin clustering. Thus, integrin-dependent modification of Lck requires PKC activity.

Figure 6.

Effect of protein kinase inhibitors on the Lck gel mobility shift. (A) Jurkat cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 50 μM of PD98059, a potent inhibitor of MEK1, for 1 d. Treated or nontreated cells (107) were clustered with either anti-β1 antibody-coated beads or with noncoated beads for 10 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with Lck antibodies and separated by 10% SDS PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse light chain antibodies and visualized by ECL. (B) Jurkat cells were treated with 5 μM PKA inhibitor 14-22 for 1 h at 37°C. The treated or nontreated cells were clustered with either anti-β1 antibody-coated beads or -noncoated beads. (C) Jurkat cells were incubated with 5 μM of bisindolylmaleimide, a specific inhibitor of PKCα, βI, βII, and γ subtypes, for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were either clustered with anti-β1 antibody-coated beads or noncoated beads. Gel mobility of Lck from these cells was detected as described above.

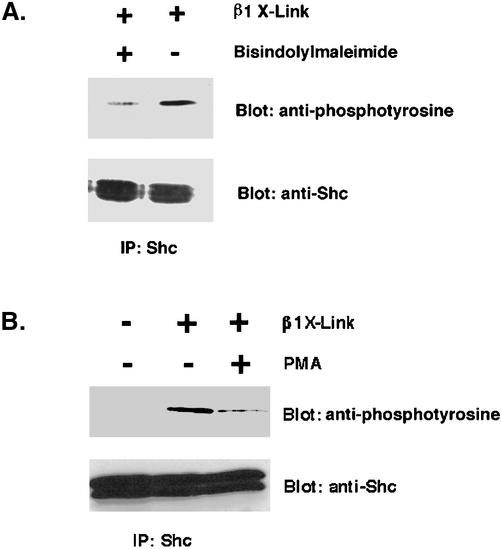

Finally, we determined whether PKC activity was required for integrin-Shc signaling in T cells. This hypothesis was tested by clustering Jurkat cells with anti-β1 integrin antibody either in the absence or presence of the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide. Strikingly, as shown in Figure 7A, inhibition of PKC activity caused a dramatic reduction in the phosphorylation of Shc. Quantitation of this experiment showed that this was a fourfold reduction. We confirmed this result by down-regulating PKC in Jurkat cells with a high-dose overnight treatment with phorbol ester, followed by clustering Jurkat cells with anti-β1 integrin antibody and assaying Shc phosphorylation (Figure 7B). This treatment also led to a dramatic reduction in integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation. Thus, PKC activity is required for both the electrophoretic mobility shift of Lck and for the efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc in T cells.

Figure 7.

Requirement of PKC activity for integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation in T cells. (A) Jurkat cells were incubated with 5 μM bisindolylmaleimide for 1 h at 37°C. Cells (107) were then clustered with either anti-β1 antibody-coated beads or noncoated beads for 10 min at 37°C, followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Shc polyclonal antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with RC-20 and visualized by ECL. (B) Effect of PMA on integrin cross-linking induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc. Jurkat cells were incubated with 70 nM of PMA for 24 h at 37°C. Cells (107) were then clustered with either anti-β1 antibody-coated or -noncoated beads for 10 min for at 37°C, followed by extraction. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Shc polyclonal antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with RC-20 and visualized with ECL. The blot then was stripped and reprobed with polyclonal anti-Shc and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Quantitation of the inhibitory effect showed approximately a fourfold reduction in Shc phosphorylation in both A and B with blockade of PKC.

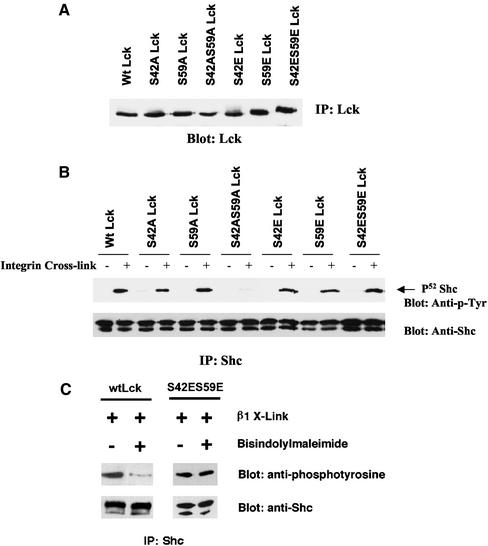

Mutants of Lck

To test directly the role of phosphorylation of Ser 42 and Ser 59 of the Lck unique amino-terminal domain, we have made mutants of Lck and expressed them in Jcam1.6 cells, which lack Lck activity. Single S→A and S→E mutants were made along with double mutants. These mutants and the wild-type Lck were then expressed in the Lck-deficient cells. Multiple clones were isolated and the analysis was done with lines expressing similar levels of Lck protein (Figure 8A). Mutation of S42A, S42E, S59A, or S59E had no effect on integrin-induced Shc phosphorylation. Strikingly, the double mutant S42A, S59A is profoundly defective in its ability to mediate integrin-mediated Shc signaling (Figure 8B). These results demonstrate that these two serine residues are required for integrin-mediated Shc phosphorylation. In contrast, when these residues were both mutated to glutamic acid, integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation was normal (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Serine 42 and serine 59 of the Lck N-terminal unique region are critical for integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation. (A) Determination of the expression levels of Wt Lck and single and double mutants of serine 42 and serine 59 to alanine (S42A, S59A and S42AS59A) or glutamic acid (S42E, S59E and S42ES59E) of Lck in Jcam 1.6 cells. Equal amounts of protein from the extracts of these stably transfected Jcam 1.6 cell lines were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-Lck antibody. The resulting immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-light chain antibodies, and visualized by ECL. Similar levels of Lck are expressed in all of the lines used. (B) Integrin-dependent Shc phosphorylation requires both the Ser 42 or Ser 59 sites in the Lck N-terminal unique region. The cell lines shown above were either left unclustered (−) or clustered with antibody beads (+) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Equal amounts of protein from the extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-Shc antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-p-Tyr (RC-20) and visualized by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Shc antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Note the markedly reduced Shc phosphorylation in S42AS59A double mutant Lck Jcam 1.6 cell line upon integrin activation, whereas the S42ES59E mutant had normal amounts of Shc phosphorylation. (C) S42E S59E Lck is resistant to inhibition of PKC. Wt Lck and S42ES59E Lck-transfected Jcam1.6 cell lines were incubated with 5 μM bisindolylmaleimide, a specific inhibitor of PKCα, βI, βII, and γ subtypes, for 1 h at 37°C or without bisindolylmaleimide. The cells were then clustered with antibody beads (+) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by extraction. Equal amounts of protein from the extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-Shc antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained for phosphotyrosine by using peroxidase-conjugated anti-p-Tyr (RC-20) and visualized by ECL. Blots were then stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Shc antibody and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Note that the S42E S59E form of Lck produced high levels (>90% of untreated) of Shc despite pretreatment with a PKC inhibitor, whereas the Wt shows a fivefold reduction (as determined by NIH Image software) in Shc phosphorylation with the same treatment.

Because we have shown that PKC signals are required for Shc phosphorylation in these cells, one would predict that the presence of negative charges at these two serines should mimic phosphorylation and may render this form of Lck resistant to PKC inhibition. Therefore, we compared the effect of the PKC inhibitor on Shc phosphorylation induced in cells expressing wild-type Lck vs. S42E S59E Lck. The results (Figure 8C) show that the presence of negative charges at these two sites does indeed provide substantial resistance (>90%) to PKC inhibitors.

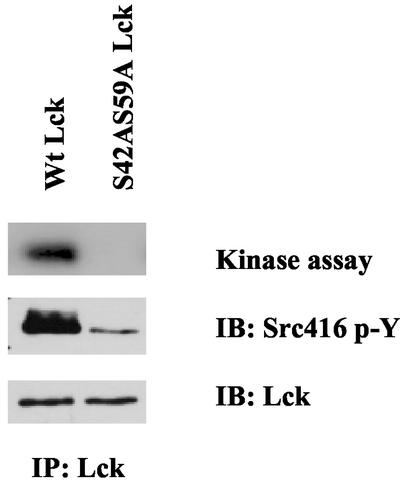

Because the double mutant S42A, S59A is defective in its ability to mediate integrin-mediated Shc signaling, we decided to determine its kinase activity. Using both autokinase assays and Western blotting for the presence of the activation loop phospho-tyrosine 394, we find that this mutant has dramatically reduced kinase activity in these cells (Figure 9). Thus, the amino terminal unique domain of Lck seems to be involved in the regulation of kinase activity.

Figure 9.

Reduced kinase activity of Lck S42AS59A. Stably transfected Jcam1.6 cell lines expressing either Wt or S42AS59A Lck were analyzed. Equal amounts of detergent extracts from the two cell lines were immunoprecipitated using monoclonal anti-Lck antibodies. Half the immune complex from each treatment was incubated in [32P]ATP in kinase buffer for 2 min at 30°C and then washed and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were soaked in KOH and then dried before autoradiography. The other half of the immune complex from each treatment was separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was stained with a polyclonal anti-phospho-Src family Tyr 416 antibody and peroxidase-conjugated protein A. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with monoclonal Lck antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated anti-light chain antibodies, and visualized by ECL. Note that despite equal amounts of Lck recovered, both the labeling by 32P and the blot measuring the activation loop tyrosine phosphorylation show severely reduced kinase activity (8- to 10-fold) in the S42AS59A Lck compared with the wild type.

DISCUSSION

The results shown in this article demonstrate a requirement for the receptor tyrosine phosphatase CD45 in the signaling of integrin to Shc. We have shown that the lack of CD45 leads to decreased Lck kinase activity, and restoration of the phosphatase activity of CD45 leads to increased Lck kinase activity. CD45 is known to be essential for TCR antigen-dependent signaling, both in cell lines and in vivo (Neel, 1997). Others have shown that the kinase activity of Lck is increased after expression of CD45 in L3 M-93 T-cell clone (Cahir McFarland et al., 1993), in peripheral blood lymphocytes (Mustelin et al., 1989), and HPB.MLT, a human CD4+8+ leukemic T-cell line (Mustelin and Altman, 1990). In Jurkat cells, CD45 expression was shown to modulate the binding of Lck to an 11-amino acid tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide containing the carboxy terminus of Lck, suggesting that CD45 could positively regulate Lck kinase activity (Sieh et al., 1993).

Our data demonstrate a requirement of CD45 for integrin signaling in T cells. In macrophages, CD45 has been shown to colocalize with integrins in focal adhesions, along with Src family kinases, and to be required for maximal adhesive activity (Roach et al., 1997). However, in this cell type, the lack of CD45 led to increased tyrosine kinase activity of Hck and Lyn, due to persistent hyperphosphorylation of the regulatory tyrosine located within the activation loop of the kinase domain. Thus, the exact role of CD45 in integrin receptor function depends on which Src family kinase members are required for these pathways in a given cell type, and how they may be activated.

In our case, we have shown that Lck activity was regulated by CD45. Furthermore, Lck-deficient cells also do not phosphorylate Shc in response to integrin clustering. Thus, we have shown that Lck is required, and at least in Jurkat and Jcam cells, Fyn does not substitute. The expression level of Fyn in these cells is very low (Denny et al., 2000), and this low expression level likely accounts for the inability of Fyn to compensate. Further experiments will be required to dissect the relative roles of these two Src family kinase members in integrin-Shc signaling in vivo. The requirement of Lck in Jurkat cells strongly suggests that many Src family members could mediate integrin-Shc signaling in different cell types. Perhaps the most prominent exception is c-Src itself, which would not substitute for Fyn in fibroblasts (Wary et al., 1998). This result may be due to differences in lipid modification, because Src associates to the membrane via a myristyl and a basic motif, whereas both Lck and Fyn share a similar lipid modification; they are myristylated and palmitylated (Resh, 1994). However, differences within cell types may also include the role of caveolin 1 vs. lymphocyte-specific proteins within lipid microdomains of the membrane, because both Lck and Fyn are associated with such domains (Brown and London, 1998).

A model has been proposed for the regulation of receptor tyrosine phosphatases, which suggests that oligomerization of these molecules is the latent state, whereas dissociation leads to activation (Weiss and Schlessinger, 1998). Thus, it is possible that integrins, for example, could bind CD45 and cause dissociation of dimers, which would activate the phosphatase domain, leading to Lck activation. We attempted to test this idea by measuring CD45 phosphatase activity in vitro after immunoprecipitation from extracts of cells untreated or treated with integrin clustering and did not find an increase in phosphatase activity. It is possible that immunoprecipitation of CD45 leads to its activation, so that we cannot measure potential increases in activity via this assay. Thus, we cannot definitively rule out a role for integrins in the regulation of CD45 activity. However, at this point, we have no evidence that CD45 activity is regulated by integrins.

The notion that Lck participates in integrin signaling raises the question of how this kinase is regulated by integrins. Our finding that cross-linking could result in a slower migration of Lck from 56 kDa to either 61 or 63 kDa may have shed some light on this problem. Based on studies on various T cells, this mobility shifting is due to phosphorylation of serine residues in the N-terminal unique region of Lck. Because these serine resides lie very close to the SH2 domain of Lck in the three-dimensional structure, the phosphorylation state of these residues is believed to be critical in determining the binding affinity and specificity of the SH2 domain of the protein (Joung et al., 1995; Park et al., 1995). For example, it has been found that a novel 62-kDa protein competes with phosphotyrosine for binding to SH2 domain of Lck when the serine 59 in the N-terminal region of Lck is phosphorylated (Park et al., 1995). The phosphorylation of these serine residues could also have an impact on the binding of potential inhibitors to Lck, or in the binding of the SH2 domain to the carboxy-terminal phosphotyrosine. In vitro, several different protein kinases, PKC/PKA, or mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase has been implicated in the shifting from 59 to 61 kDa and from 59 to 63 kDa, respectively (Winkler et al., 1993). Although our data show that the phosphorylation is dependent on PKC, we do not know whether this is the only protein kinase involved. Serine 59 is most likely phosphorylated by a proline-dependent kinase, consistent with the surrounding sequence within Lck (Winkler et al., 1993). In vitro, MAP kinase can mediate this phosphorylation; however, the lack of an effect by the MEK inhibitor, shown in Figure 6, suggests that either another proline-dependent kinase is involved or that a MEK-independent MAP kinase activation is involved. Because another group has shown that a PKA-dependent serine phosphorylation of Src is critical in its regulation (Schmitt and Stork, 2002), it is possible that these modifications of the unique amino-terminal domain of Src family kinases are a common, general mechanism for regulation. Further experiments will be necessary to determine the mechanism of this profound effect (8- to 10-fold reduction in kinase activity of the S42AS59A mutant).

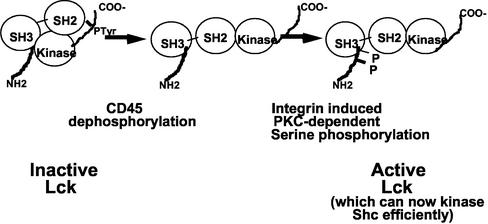

Our results suggest a working model for integrin-dependent phosphorylation of Shc in T cells (Figure 10). Upon integrin clustering, there is a PKC-dependent phosphorylation of Lck, which may alter its binding to a number of partners, allowing for a portion of it to bind and phosphorylate Shc. This phosphorylation is dependent on the previous cleavage of the COOH terminal pTyr by CD45 (Figure 5C). Although PKC activation is clearly required, it is likely that clustering is a critical feature, because the phospho-mimic mutant (S42ES59E) does not phosphorylate Shc in the absence of cross-linking (Figure 8B). Most likely, Lck would bind to Shc through its SH3 domain, as has been shown for Fyn and Shc (Wary et al., 1998). Lck, like Fyn, then phosphorylates Shc on tyrosine 317, which is a potent Grb2 binding site. Interestingly, others (Miranti et al., 1999) have shown that PKC is required for optimal integrin-Shc signaling in Cos cells, where Fyn is the most likely kinase. The experiments performed in this study were done using fibronectin adhesion to trigger signaling, and perturbation of PKC affected cell spreading as well as Shc signals, although FAK signaling was spared. Thus, the exact basis for PKC requirement in Cos cells could be similar as we propose for Lck in Jurkat cells, but more experiments will be necessary to determine whether this is the case.

Figure 10.

Model of Integrin signaling through Lck to Shc.

Future directions for this work will hopefully answer a number of important questions that remain open. The mechanism of integrin-dependent PKC activation remains unclear but may involve PLCγ isoforms binding to FAK. In addition, it is unclear which PKC isoforms are involved; however, it is intriguing to speculate that PKCθ, which is a central player in T-cell signaling at the immunological synapse (Isakov and Altman 2002), may be involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge G. Koretzky (University of Pennsylvania) for Jurkat cell lines and for advice. We are especially indebted to D. Straus (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA) for the Jcam.1.6 cells and the pBP1 vector and for critical advice on the generation of the cell lines. We also thank members of the Marcantonio laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-44585).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0382. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0382.

REFERENCES

- Anderson SJ, Perlmutter RM. A signaling pathway governing early thymocyte maturation. Immunol Today. 1995;16:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, London E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byth KF, Conroy LA, Howlett S, Smith AJ, May J, Alexander DR, Holmes N. CD45-null transgenic mice reveal a positive regulatory role for CD45 in early thymocyte development, in the selection of CD4 + CD8 + thymocytes, and B cell maturation. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1707–1718. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahir McFarland ED, Hurley TR, Pingel JT, Sefton BM, Shaw A, Thomas ML. Correlation between Src family member regulation by the protein-tyrosine-phosphatase CD45 and transmembrane signaling through the T-cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1402–1406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casnellie JE, Lamberts RJ. Tumor promoters cause changes in the state of phosphorylation and apparent molecular weight of a tyrosine protein kinase in T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4921–4925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny MF, Patai B, Straus DB. Differential T-cell antigen receptor signaling mediated by the Src family kinases Lck and Fyn. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1426–1435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1426-1435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai DM, Sap J, Schlessinger J, Weiss A. Ligand-mediated negative regulation of a chimeric transmembrane receptor tyrosine phosphatase. Cell. 1993;73:541–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90141-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einspahr KJ, Abraham RT, Dick CJ, Leibson PJ. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and p56lck modification in IL-2 or phorbol ester-activated human natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:1490–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith MA, Weiss A. Isolation and characterization of a T-lymphocyte somatic mutant with altered signal transduction by the antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6879–6883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak ID, Gress RE, Lucas PJ, Horak EM, Waldmann TA, Bolen JB. T-lymphocyte interleukin 2-dependent tyrosine protein kinase signal transduction involves the activation of p56lck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1996–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovis RR, Donovan JA, Musci MA, Motto DG, Goldman FD, Ross SE, Koretzky GA. Rescue of signaling by a chimeric protein containing the cytoplasmic domain of CD45. Science. 1993;260:544–546. doi: 10.1126/science.8475387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakov N, Altman A. Protein kinase C(θ) in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:761–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung I, Kim T, Stolz LA, Payne G, Winkler DG, Walsh CT, Strominger JL, Shin J. Modification of Ser59 in the unique N-terminal region of tyrosine kinase p56lck regulates specificity of its Src homology 2 domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5778–5782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann SA, Dell CL, Hunt SW, Shimizu Y. Genetic analysis of integrin activation in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:172–188. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Briesewitz R, Bank I, Marcantonio EE. The role of the I domain in ligand binding of the human integrin α1β1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22811–22816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinghoffer RA, Sachsenmaier C, Cooper JA, Soriano P. Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. EMBO J. 1999;18:2459–2471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretzky GA, Kohmetscher MA, Kadleck T, Weiss A. Restoration of T cell receptor-mediated signal transduction by transfection of CD45 cDNA into a CD45-deficient variant of the Jurkat T cell line. J Immunol. 1992;149:1138–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretzky GA, Picus J, Schultz T, Weiss A. Tyrosine phosphatase CD45 is required for T-cell antigen receptor and CD2-mediated activation of a protein tyrosine kinase and interleukin 2 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2037–2041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretzky GA, Picus J, Thomas ML, Weiss A. Tyrosine phosphatase CD45 is essential for coupling T-cell antigen receptor to the phosphatidyl inositol pathway. Nature. 1990;346:66–68. doi: 10.1038/346066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero F, Murgia C, Wary KK, Curatola AM, Pepe A, Blumemberg M, Westwick JK, Der CJ, Giancotti FG. The coupling of alpha6beta4 integrin to Ras-MAP kinase pathways mediated by Shc controls keratinocyte proliferation.“. EMBO J. 1997;16(9):2365–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero F, Pepe A, Wary KK, Spinardi L, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Giancotti FG. Signal transduction by the α6β4 integrin: distinct β4 subunit sites mediate recruitment of Shc/Grb2 and association with the cytoskeleton of hemidesmosomes. EMBO J. 1995;14:4470–4481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranti CK, Ohno S, Brugge JS. Protein kinase C regulates integrin-induced activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway upstream of Shc. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10571–10581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustelin T, Altman A. Dephosphorylation and activation of the T cell tyrosine kinase pp56lck by the leukocyte common antigen (CD45) Oncogene. 1990;5:809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustelin T, Coggeshall KM, Altman A. Rapid activation of the T-cell tyrosine protein kinase pp56lck by the CD45 phosphotyrosine phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6302–6306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel BG. Role of phosphatases in lymphocyte activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:405–420. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh ES, Gu H, Saxton TM, Timms JF, Hausdorff S, Frevert EU, Kahn BB, Pawson T, Neel BG, Thomas SM. Regulation of early events in integrin signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3205–3215. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park I, Chung J, Walsh CT, Yun Y, Strominger JL, Shin J. Phosphotyrosine-independent binding of a 62-kDa protein to the src homology 2 (SH2) domain of p56lck and its regulation by phosphorylation of Ser-59 in the lck unique N-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12338–12342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph SJ, Thomas ML, Morton CC, Trowbridge IS. Structural variants of human T200 glycoprotein (leukocyte-common antigen) EMBO J. 1987;6:1251–1257. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Myristylation and palmitylation of Src family members: the fats of the matter. Cell. 1994;76:411–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach T, Slater S, Koval M, White L, Cahir McFarland ED, Okumura M, Thomas M, Brown E. CD45 regulates Src family member kinase activity associated with macrophage integrin-mediated adhesion. Curr Biol. 1997;7:408–417. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeissner PJ, Xie H, Smilenov LB, Shu F, Marcantonio EE. Integrin functions play a key role in the differentiation of thymocytes in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:3715–3724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt JM, Stork PJ. PKA phosphorylation of Src mediates cAMP's inhibition of cell growth via Rap1. Mol Cell. 2002;9:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, van Seventer GA, Horgan KJ, Shaw S. Roles of adhesion molecules in T-cell recognition: fundamental similarities between four integrins on resting human T cells (LFA-1, VLA-4, VLA-5, VLA-6) in expression, binding, and costimulation. Immunol Rev. 1990;114:109–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1990.tb00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroo M, Goff L, Biffen M, Shivnan E, Alexander D. CD45 tyrosine phosphatase-activated p59fyn couples the T cell antigen receptor to pathways of diacylglycerol production, protein kinase C activation and calcium influx. EMBO J. 1992;11:4887–4897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicheri F, Moarefi I, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature. 1997;385:602–609. doi: 10.1038/385602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieh M, Bolen JB, Weiss A. CD45 specifically modulates binding of Lck to a phosphopeptide encompassing the negative regulatory tyrosine of Lck. EMBO J. 1993;12:315–321. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims TN, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: integrins take the stage. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:100–117. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus DB, Weiss A. Genetic evidence for the involvement of the lck tyrosine kinase in signal transduction through the T cell antigen receptor. Cell. 1992;70:585–593. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90428-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Muranjan M, Sap J. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha activates Src-family kinases and controls integrin-mediated responses in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 1999;9:505–511. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veillette A, Horak ID, Horak EM, Bookman MA, Bolen JB. Alterations of the lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (p56lck) during T-cell activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4353–4361. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volarevic S, Niklinska BB, Burns CM, June CH, Weissman AM, Ashwell JD. Regulation of TCR signaling by CD45 lacking transmembrane and extracellular domains. Science. 1993;260:541–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8475386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walk SF, March ME, Ravichandran KS. Roles of Lck, Syk and ZAP-70 tyrosine kinases in TCR-mediated phosphorylation of the adapter protein Shc. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2265–2275. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2265::AID-IMMU2265>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wary KK, Mainiero F, Isakoff SJ, Marcantonio EE, Giancotti FG. The adaptor protein Shc couples a class of integrins to the control of cell cycle progression. Cell. 1996;87:733–743. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Littman DR. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Schlessinger J. Switching signals on or off by receptor dimerization. Cell. 1998;94:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DG, Park I, Kim T, Payne NS, Walsh CT, Strominger JL, Shin J. Phosphorylation of Ser-42 and Ser-59 in the N-terminal region of the tyrosine kinase p56lck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5176–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Harrison SC, Eck MJ. Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature. 1997;385:595–602. doi: 10.1038/385595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]