Abstract

Quantitative PCR (QPCR) technology, incorporating fluorigenic 5′ nuclease (TaqMan) chemistry, was utilized for the specific detection and quantification of six pathogenic species of Candida (C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata and C. lusitaniae) in water. Known numbers of target cells were added to distilled and tap water samples, filtered, and disrupted directly on the membranes for recovery of DNA for QPCR analysis. The assay's sensitivities were between one and three cells per filter. The accuracy of the cell estimates was between 50 and 200% of their true value (95% confidence level). In similar tests with surface water samples, the presence of PCR inhibitory compounds necessitated further purification and/or dilution of the DNA extracts, with resultant reductions in sensitivity but generally not in quantitative accuracy. Analyses of a series of freshwater samples collected from a recreational beach showed positive correlations between the QPCR results and colony counts of the corresponding target species. Positive correlations were also seen between the cell quantities of the target Candida species detected in these analyses and colony counts of Enterococcus organisms. With a combined sample processing and analysis time of less than 4 h, this method shows great promise as a tool for rapidly assessing potential exposures to waterborne pathogenic Candida species from drinking and recreational waters and may have applications in the detection of fecal pollution.

Yeasts are a significant component of the microbiota of most natural aquatic ecosystems (17, 33) and can also occur in drinking water distribution systems as a result of their ability to survive treatment practices and become incorporated into biofilms (6, 12, 22, 30, 31). The majority of these organisms have no known human health effect. However, a small number of species, primarily within the anamorphic genus Candida, are important opportunistic pathogens (23).

The importance of pathogenic Candida as agents of nosocomial infections has led to the development of a number of modern molecular diagnostic methods to facilitate their detection and identification in clinical samples. Methods based on the PCR and DNA hybridization probes have received particular attention (9, 25, 26, 32, 39). The more recent advent of fluorescent probe-based PCR technology (21) has led to the development of homogeneous methods for detecting these organisms that require relatively short periods of time to perform (16, 28).

Quantitative PCR (QPCR) has been demonstrated to be useful for quantitative analysis of microorganisms in environmental samples (29, 34, 35, 36), but, to our knowledge, this approach has not been used in the analysis of yeasts in water. Analyses for pathogenic yeasts in drinking or recreational water systems have the potential to expedite the identification of possible health hazards resulting either directly from the presence of these organisms or, as their presence might indicate, indirectly from other waterborne pathogens.

The first objective of this study was to develop QPCR technology, incorporating fluorigenic 5′ nuclease (TaqMan) chemistry, for specifically detecting and quantifying six common pathogenic species of Candida, namely, C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, and C. lusitaniae. The second objective was to evaluate a simple and rapid method, using QPCR, for the detection and enumeration of these organisms in different types of water samples. Finally, the method was compared with conventional plating and culturing methods in the analysis of a series of freshwater samples collected from a recreational beach on Lake Michigan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast cultures.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. For preparation of cell stocks, Geotrichum candidum cultures were grown for several weeks on potato dextrose agar (Becton and Dickinson, Fairfax, Va.), and the other cultures were grown on yeast mannitol agar (Becton and Dickinson) for 24 to 48 h at room temperature. Cells were harvested by using a moistened, sterile cotton swab and resuspended in sterile water containing 0.05% Tween 80. Suspended cell stock concentrations were determined by counting in a hemocytometer chamber at 400× magnification as previously described (29), and 50- to 100-μl aliquots were stored at −80°C. Aliquots of G. candidum stocks, containing 2 × 106 cells, and aliquots of different Candida and other yeast cell stocks, containing between 104 and 105 cells, were added as external references and target organisms, respectively, to calibrator samples for QPCR analysis, as previously described (19, 29), or were used as sources of known cell quantities for various experiments described below.

TABLE 1.

Fungal cultures, sources, and GenBank accession numbers of organisms used in this research

| Species | Source and strain no.a | GenBank sequence accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | ATCC 18804 | U45776 |

| C. albicans | ATCC 11006 | |

| C. albicans | ATCC 14053 | |

| C. albicans | ATCC 24433 | |

| C. albicans | ATCC 36232 | |

| C. albicans | ATCC 60193 | |

| C. albicans | ATCC 66027 | |

| C. dubliniensis | NRRL Y-17841 | U57685 |

| C. glabrata | ATCC 2001 | U44808 |

| C. glabrata | ATCC 66032 | |

| C. glabrata | NRRL Y-17815 | |

| C. guilliermondiib | NRRL Y-2075 | U45709 |

| C. guilliermondii | ATCC 6260 | |

| C. haemulonii | NRRL Y-6693 | U44812 |

| C. haemulonii type II | NRRL Y-17801 | U44819 |

| C. insectamans | ATCC 22874 | U45753 |

| C. kruseic | NRRL Y-5396 | U76347 |

| C. krusei | ATCC 6258 | |

| C. krusei | ATCC 14243 | |

| C. lipolyticad | NRRL YB-423 | U40080 |

| C. lusitaniaee | NRRL Y-11827 | U44817 |

| C. lusitaniae | ATCC 42720 | |

| C. lusitaniae | ATCC 66035 | |

| C. lusitaniae | NRRL Y-5393 | |

| C. lusitaniae | NRRL Y-11826 | |

| C. lyxosophila | NRRL Y-17539 | U76204 |

| C. maltosa | NRRL Y-17677 | U45745 |

| C. maltosa | UGA R-42 | |

| C. parapsilosis | ATCC 22019 | U45754 |

| C. parapsilosis | NRRL Y-7363 | |

| C. parapsilosis | NRRL Y-543 | |

| C. sake | ATCC 14478 | U45728 |

| C. sojae | NRRL Y-17909 | U71070 |

| C. tropicalis | ATCC 750 | U45749 |

| C. tropicalis | UGA 52-71 | |

| C. tropicalis | ATCC 13803 | |

| C. tropicalis | ATCC 66029 | |

| C. viswanathii | ATCC 22981 | U45752 |

| C. zeylanoides | NRRL Y-1774 | U45832 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ATCC 14116 | AF189845 |

| Geotrichum candidum | UAMH 7863 | AF157596 |

| Pichia angusta | ATCC 34438 | U75524 |

| Lodderomyces elongisporus | ATCC 11503 | U45763 |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | ATCC 9449 | AF189960 |

| Trichosporon cutaneum | ATCC 28592 | AF075483 |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; NRRL, Northern Regional Research Laboratory, U.S. Department of Agriculture; UGA, University of Georgia; UAMH, University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium.

Pichia guilliermondii, as renamed (24).

Issatchenkia orientalis, as renamed (24).

Yarrowia lipolytica, as renamed (24).

Clavispora lusitaniae, as renamed (24).

Cell suspension and collection filter extractions.

Yeast cell suspensions used as calibrator samples or for determining assay specificity, amplification efficiency, and cell detection limits were extracted by a rapid bead-milling method (20). Ten-microliter aliquots of both target yeast and G. candidum reference cell stocks were combined with 200 μl of AE buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) in a 2.0-ml conical-bottom, screw-cap tube (PGC Scientifics, Gaithersburg, Md.) containing 0.3 g of acid-washed glass beads (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The tubes were shaken in a mini bead-beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) for 1 min at the maximum rate and then centrifuged in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 3 min. The genomic DNA in the supernatant above the beads was transferred to a sterile microfuge tube and stored at −80°C. In some cases, the extracts were further purified by use of a Qiagen purification kit procedure. This procedure was performed by adding 300 μl of binding buffer from an Elu-Quik DNA purification kit (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.) to 100 μl of the supernatant indicated above and purifying on a DNeasy glass filter column (Qiagen), as previously described (20).

Collection filter extractions (CFE) were performed with polycarbonate filters (Osmonics Inc., Minnetonka, Minn.) used to recover cells from water samples. After filtration of the water samples on a manifold device, the filters were placed in 2.0-ml conical-bottom, screw-cap tubes containing 0.3 g of acid-washed glass beads, 10 μl of G. candidum reference cell stock, and 200 μl of AE buffer; they were then disrupted by bead milling, and DNA was recovered, as described above. These extracts were also further purified, in some instances, by use of a Qiagen purification kit procedure (CFE+Q), as described above.

Design of TaqMan primer and probe sets.

The QPCR assays targeted the variable D1/D2 domains of the nuclear large subunit (LSU) ribosomal gene. Sequences from virtually all known ascomycetous yeast species have been determined for this region (24), which facilitated the design and testing of the assays for species specificity. Table 1 lists the GenBank accession numbers for the target species and other organisms that were experimentally examined. Phylogenetic analysis, based on the LSU DNA sequences, has placed the six target species in four different clades (24). Therefore, four alignments were made that included sequences of the target species and those of relatives in their respective clades by using the MegAlign program of the Lasergene Biocomputing software package (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Manual searches of the alignments were conducted to determine species-specific candidate primer sequences. The candidate primer sequences for each of the target species were analyzed in the Oligo 6 primer analysis software program (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., Cascade, Colo.) for primer stability (e.g., optimal melting temperature, potential primer-dimer formation, and hairpin structures) and predictions of false priming of the corresponding sequences of all nontarget species in their respective clades (18, 19). Final selection of primer and probe sequence lengths and determinations of their compatibility with the fluorigenic 5′ nuclease assay were performed by using the ABI Primer Express program (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The primer and probe sequences in Table 2 were custom synthesized at the Applied Biosystems oligonucleotide factory. The probes contained the reporter dye 6-FAM linked to the 5′-terminal nucleotide and the quencher dye TAMRA conjugated to the 3′ end. The primers and probe used in the G. candidum reference assay have been previously described (19).

TABLE 2.

The QPCR primer and probe sequences developed for the identification and quantification of pathogenic Candida species in water

| Target species (assay abbre- viation) | Primer/ probe namea | Primer/probe sequence |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans (Calb) | Calb F1 | 5′-CTTGGTATTTTGCATGTTGCTCTC-3′ |

| Calb R1 | 5′-GTCAGAGGCTATAACACACAGCAG-3′ | |

| Calb P1 | 5′-TTTACCGGGCCAGCATCGGTTT-3′ | |

| C. glabrata (Cglab) | Cglab F1 | 5′-GCGCCCCTTGCCTCTC-3′ |

| Cglab R1 | 5′-CCCAGGGCTATAACACTCTACACC-3′ | |

| Cglab P1 | 5′-TGGGCTTGGGACTCTCGCAGC-3′ | |

| C. parapsilosis (Cpar) | Cpar F1 | 5′-GATCAGACTTGGTATTTTGTATGTTACTCTC-3′ |

| Cpar R1 | 5′-CAGAGCCACATTTCTTTGCAC-3′ | |

| Cpar P1 | 5′-CCTCTACAGTTTACCGGGCCAGCATCA-3′ | |

| C. tropicalis (Ctrop) | Ctrop F1 | 5′-GCGGTAGGAGAATTGCGTT-3′ |

| Ctrop R2 | 5′-TCATTATGCCAACATCCTAGGTTTA-3′ | |

| Ctrop P2 | 5′-CGCAGTCCTCAGTCTAGGCTGGCAG-3′ | |

| C. lusitaniae (Clus) | Clus F2 | 5′-GGGAATTGTAATTTGAAGGTTTCGT-3′ |

| Clus R2 | 5′-GTCGGCGTGCGCCATA-3′ | |

| Clus P2 | 5′-TCTGAGTCGGCCGCGCCC-3′ | |

| C. krusei (Ckru) | Ckru F1 | 5′-CTCAGATTTGAAATCGTGCTTTG-3′ |

| Ckru R1 | 5′-GGGGCTCTCACCCTCCTG-3′ | |

| Ckru P1 | 5′-CACGAGTTGTAGATTGCAGGTTGGAGTCTG-3′ |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; P, probe.

QPCR reactions.

Reactions were performed in 0.5-ml thin-walled, optical-grade PCR tubes (Applied Biosystems) by addition of the following components: 12.5 μl of TaqMan Universal Master Mix, a 2× concentrated, proprietary mixture of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, AmpErase UNG, deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates with UTP, passive reference dye, and optimized buffer components; 5 μl of a mixture of forward and reverse primers (5 μM each) and 400 nM TaqMan probe; and 2.5 μl of a 2-mg/ml concentration of bovine serum albumin (fraction V, Sigma) and 5 μl of DNA template. The reactions were monitored in an Applied Biosystems Prism model 7700 sequence detection instrument. Thermal cycling conditions consisted of 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Determinations of cycle threshold (CT) were performed automatically by the instrument.

Quantities of target cells in each test sample were determined by using the ΔΔCT comparative cycle threshold method, as previously described (User Bulletin no. 2 [1997], ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems) and then modified (19, 29). Briefly, this method determines the relative quantity of target DNA sequences extracted from an unknown test sample compared to the quantity of target sequences extracted from a known quantity of target organisms in a calibrator sample. This is done after normalizing for the relative recoveries of total DNA in the extraction process from the two samples by comparing the recovered quantities of another sequence from an external reference organism added in equal cell numbers to both. For each test sample and corresponding calibrator sample reaction, a ΔCT value is obtained by subtracting the CT value of the reference sequence assay (CTref) from the CT value of the target sequence assay (CTtarget). A ΔΔCT value is obtained by subtracting the ΔCT value of the calibrator sample from the ΔCT value of the test sample. The ratio of target sequences in the test and calibrator samples is described by  , where E is the amplification efficiency of the target assay. These ratios are multiplied by the known number of target organism cells in the calibrator samples to obtain estimates of the numbers of target cells in each test sample.

, where E is the amplification efficiency of the target assay. These ratios are multiplied by the known number of target organism cells in the calibrator samples to obtain estimates of the numbers of target cells in each test sample.

Specificity of Candida QPCR assays.

The specificity of each Candida assay was verified experimentally by using the array of species listed in Table 1. DNA extracts were prepared as described above from 10 μl of the suspended cell stocks of one representative strain (the type strain in all cases where available) from each species mixed with G. candidum reference cells. These extracts were analyzed in duplicate reactions on the model 7700 Sequence Detector for each of the six target species assays (the appropriate primers and probe are as shown in Table 2). A CT value of 40 (maximum number of PCR cycles run) indicated that DNA from the test strain was not detected.

Amplification efficiencies and extrapolated sensitivities of Candida QPCR assays.

DNA extracts were prepared, as described above, from suspended cell stocks of each of the target species strains listed in Table 1. Tenfold serial dilutions of these DNA extracts were analyzed by QPCR by using the appropriate primer and probe sets. Each of the undiluted extracts was also analyzed by using the G. candidum reference assay. ΔCT values were calculated by subtracting the reference assay result for each extract from the target assay results for each dilution from that extract. For the purpose of estimating minimum cell detection limits, the mean reference CT result for all strains was added back to each of the individual ΔCT values to give normalized target assay CT values. These values were plotted against the log transformed cell equivalents in the samples (i.e., the target cell numbers in the original extracts divided by the extract dilution factor) to calculate amplification efficiencies and extrapolated cell detection limits.

Ideally the amplification efficiency (E) of a PCR assay is equal to 2; that is, there is a doubling of the number of copies during each cycle (User Bulletin no. 2 [1997], ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System). However, a single cycle may result in less than a doubling, and the latter of the two equations below can be used to estimate E. The relationship of the difference in cycle threshold between target and reference cells (ΔCT) to the number of target cells or cell equivalents (N) in an extracted sample is related to amplification efficiency by the equation N = M ·  (where M is a constant of proportionality), or by the equation ΔCT = CT target − CTref = a + b · log10(N), where a = log10(M)/log10(E) and b = −1/log10(E). This latter equation also can be used to ascertain whether the amplification efficiency is the same for two different organisms, since in that case their respective slopes will be equal, i.e., their regressions will be parallel.

(where M is a constant of proportionality), or by the equation ΔCT = CT target − CTref = a + b · log10(N), where a = log10(M)/log10(E) and b = −1/log10(E). This latter equation also can be used to ascertain whether the amplification efficiency is the same for two different organisms, since in that case their respective slopes will be equal, i.e., their regressions will be parallel.

The sensitivity or minimum detection limit of this method is dependent on the threshold being attained within 40 cycles, i.e., CT < 40. Thus, extrapolation of the regression line (by the latter equation above) to a CT value of 40 provides an estimate of the minimum cell detection limit for each strain. The value of the detection limit, therefore, depends on the intercept and slope of this regression, as well as the extraction efficiency and quality of the DNA in the extracts, which are reflected in the reference cycle threshold, CTref. If assays among different strains of the same species are parallel, then, for any given level of extraction efficiency and DNA quality, the detection limits of the various strains will differ only if their intercepts differ.

Experimental analysis of assay sensitivity or minimum detection limit.

To experimentally assess the sensitivity or minimum detectable cell number, solid-phase cytometry with a Scan RDI instrument (Chemunex, Maisons Alfort, France) was used. Solid-phase cytometry involves the direct detection and enumeration of fluorescently labeled cells that have been collected on membrane filters. The Scan RDI instrument automates this process and allows for rapid visual confirmation by microscopy of the fluorescently detected cells.

Cultures of C. albicans were grown for 24 to 48 h in yeast-mannitol broth at 37°C in a shaking incubator. The cultures were then washed twice with 1 ml of filter-sterilized Isoton (Coulter, Miami, Fla.) at a pH of 8.0 and collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm. The washed cells were suspended in Isoton, and aliquots were counted in a hemocytometer chamber. Dilutions with different cell concentrations were made from the suspensions, and 1-ml volumes were stained with 5 μl of the general nucleic acid stain Syto 16 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) for 10 min and then filtered through 25-mm-diameter, 0.4-μm-pore-size, polyethylene terephthalate membranes filters (ChemFilter, Chemunex). The cells were enumerated by using a Scan RDI in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Each cell identified by the instrument was manually validated by microscopy at 400× magnification with a Nikon Eclipse E600 epifluorescence microscope (Fryer, Inc., Huntley, Ill.) by using a 450- to 490-nm excitation filter and a >520-nm emission filter. The cells on the collection filters were then extracted by using the CFE method and quantified by QPCR and by the ΔΔCT comparative CT calculation as described above.

Analysis of tap and surface water samples.

Tap, pond, and river water samples were collected locally in Cincinnati, Ohio. Water samples were collected by following quality control guidelines described in sections 9600 A and B of Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (15). Turbidity readings for the water samples were made by using a model 2100N tubidimeter (Hach, Ames, Iowa) and were expressed in nephelometric turbidity units (NTU). Different dilutions of C. albicans stock cell suspensions were enumerated by solid-phase cytometry, and from these enumerations, known cell quantities in the diluted cell suspensions were spiked into the water samples. The spiked water samples (1,000 ml of tap, 100 ml of pond, and 20 ml of river water) were filtered through 47-mm-diameter, 0.4-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters (Osmonics Inc.). Both the CFE and CFE+Q methods, described above, were used to recover DNA.

Inhibition of QPCR reactions was evaluated by preliminary analyses of parallel dilutions of each test sample and calibrator extract with the G. candidum reference assay. Determinations of appropriate dilutions required for relief of inhibition were made by finding the dilution where the test sample and calibrator CTref values coincided (29). Test sample and calibrator extracts of the appropriate dilution were then analyzed with the target and reference assays, and target cells were enumerated by using the ΔΔCT comparative CT calculation.

Collection of Lake Michigan beach water samples.

Grab samples of Lake Michigan beach water were collected weekly at Mount Baldy beach in Indiana from August 13, 2001 until September 24, 2001. Samples were collected by following the general quality control guidelines indicated above and those in section 3 of Improved Enumeration Methods for the Recreational Water Quality Indicators: Enterococci and Escherichia coli (38).

Enumeration of viable Enterococcus organisms in Lake Michigan beach water samples.

Enterococcus populations were determined in each of the Lake Michigan water samples by using EPA Method 1600 (37). Water samples (3 to 100 ml) were filtered through 47-mm-diameter, 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filters. The filters were placed on mEI agar (Hach) and incubated at 41°C for 24 h. Enumeration of the enterococci was performed by counting any colonies with a blue halo, in accordance with the method instructions.

Enumeration of organisms of pathogenic Candida species in Lake Michigan beach water samples.

Enumeration of CFU of target species was performed by using a modification of the ASTM standard method for enumeration of Candida species in water (1). This method consisted of filtering water samples (100 to 300 ml) through 47-mm-diameter, 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filters (Pall, East Hills, N.Y.), placing the filters on the surface of BiGGY agar (Becton and Dickinson) with 5 mg of chloramphenicol/ml, and incubating at 37°C for 48 h. We replaced the mCA medium specified in the standard method because earlier studies in our laboratory had demonstrated that at 37°C, BiGGY agar with chloramphenicol supports the growth of all of the target species in this investigation, while suppressing growth of bacteria.

To quantify the colony-forming population of each species of Candida in the sample, up to 50 Candida colonies were randomly picked from each of the plated samples. The isolates were streaked for individual colonies on BiGGY agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Isolated colonies from these plates were inoculated into yeast-mannitol broth and incubated with shaking for 48 h at 37°C. Before the cells in the broth cultures were harvested, optical density readings of each culture were taken at 560 nm with a Spectronic Genesys 5 spectrometer (Spectronic Instruments, Rochester, N.Y.). Based on these readings, different volumes of the cultures were diluted to 1 ml with distilled water so that approximately the same quantities of cells were harvested for each isolate. Culture medium was removed from the diluted cell suspensions after centrifuging for 3 min at 14,000 rpm, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 1.0 ml of sterile, distilled water. Aliquots of the suspensions were extracted as described above without purification and analyzed by the panel of QPCR assays for the six different target species. These analyses allowed the cultured isolates of each of the target species to be identified on the basis of their responses (i.e., CT values) in the different assays. From these analyses, the percentage of each target species making up the sampled population was determined and these percentages were then multiplied by the total number of CFU counted from the respective water sample platings to obtain estimates of the number of CFU attributable to each species.

For direct QPCR analysis of target Candida species in the Lake Michigan water samples, 100- to 300-ml volumes were filtered through polycarbonate filters, and the filters were extracted by the CFE method. Inhibition of QPCR reactions was determined as described above. Test sample extracts requiring more than a tenfold dilution were further purified by using the CFE+Q method. The variously processed and diluted test sample extracts and correspondingly processed and diluted calibrator extracts were analyzed with the target and reference QPCR assays, and target cell quantities in the test samples were determined by the ΔΔCT comparative CT calculation.

Species verification of PCR amplicons from Lake Michigan water samples by sequence analysis.

DNA extracts from the water samples collected during weeks 1 and 4 of the study, which gave the most diverse ranges of positive QPCR results for the different target Candida species, were amplified with a conventional PCR kit (Expand High Fidelity, Boehringer Manheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) by using the same species-specific primer sets without probes and otherwise identical reaction conditions. The double-stranded products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and SYBR Green I (BioWhitaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, Maine) staining and subjected to purification and direct nucleotide sequencing analysis with the same primers in an Applied Biosystems model 373A DNA sequencer, as previously described (18).

RESULTS

Specificity, amplification efficiency, and extrapolated minimum detection limits of QPCR assays.

None of the different Candida QPCR assays were positive for any of the organisms listed in Table 1 except for strains of the intended target species listed in Table 2. These results were consistent with the predictions of the Oligo 6 primer analysis program in all instances (results not shown). Analyses in the Oligo 6 program of these primer and probe sets with the rDNA sequences of other species, unavailable for experimental analysis in this study but shown by phylogenetic analyses to be related to the target species (24), indicated that these species would also fail to be detected.

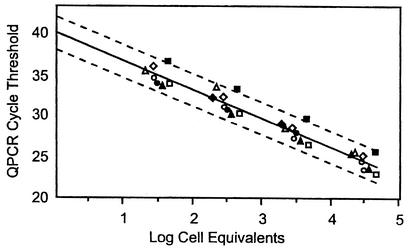

Table 3 shows the amplification efficiencies and average minimum cell detection limits for each assay, as determined from regressions of log transformed cell equivalents on the normalized CT values for each strain of the respective target species. Representative data used in these regressions are illustrated in Fig. 1 for C. albicans. Parallelism of the regressions for each strain was tested by means of an F test on the marginal mean squares resulting from the extra sums of squares for the parallel model, in which a common slope parameter was used for all strains, compared to the error mean square of the nonparallel model, in which a unique slope parameter was estimated for each strain. In either case, the intercept parameters were allowed to vary among strains. Given no significant differences in the slopes of the strains within any of the target species (data not shown), parallelism across species was then evaluated in a similar manner, constraining the slope parameter to a single value for all species. Slight variations were seen in the amplification efficiencies of the different species (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Assay, amplification efficiency, and mean extrapolated cell detection limits of Candida species tested by using the QPCR methoda

| Yeast species | Assay | Amplification efficiencyb | Mean cell detection limit ± SDb |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | Calb | 1.95 | 1.07 ± 0.74 |

| C. glabrata | Cglab | 2.00 | 0.47 ± 0.11 |

| C. krusei | Ckru | 1.89 | 0.55 ± 0.091 |

| C. lusitaniae | Clus | 1.90 | 0.73 ± 0.46 |

| C. parapsilosis | Cpar | 1.92 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| C. tropicalis | Ctrop | 1.91 | 0.083 ± 0.04 |

Cell detection for all other species tested, as listed in Table 1, were negative. DNA extracts from at least 104 cells of each of the nontarget species were analyzed.

Amplification efficiencies and extrapolated cell detection limits were determined as described in the text and illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Determination of amplification efficiency and extrapolated cell detection limit for QPCR analysis of Candida species, showing C. albicans as an example. DNA extracts were prepared by a rapid bead-milling method, as described in the text, from cell stocks of known concentration (determined by hemocytometer counts) of the strains ATCC 18804 (◊), ATCC11006 (⧫), ATCC 14053 (▴), ATCC 60193 (▵), ATCC 18804 (•), ATCC 24433 (○), ATCC 66027 (▪) (experiment 1), and ATCC 66027 (□) (experiment 2). In this example, there was no lack of fit for a parallel relationship (P = 0.729), and thus the amplification efficiencies were presumed to be equal. The regression of log cell equivalents on CT is represented by a single solid line. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limits for the individual results.

Extrapolation of the regression lines to a CT value of 40 provided estimates of the minimum cell detection limits for each strain. In order to measure inherent experimental variability in these results, we performed duplicate experiments on five different strains within four of the studied Candida species. Results from these five duplicate sets were pooled to obtain an estimate of experimental variance. For each species, the variance across strains, as given by the mean squares among strains, was compared to the pooled experimental variance for the duplicate analyses via an F test in order to determine whether it may be reasonable to attribute any observed variability between strains to normal experimental variability. These analyses indicated that the differences in extrapolated detection limits seen among the strains in each species could be attributed to experimental variability.

Experimental analysis of method sensitivity and accuracy.

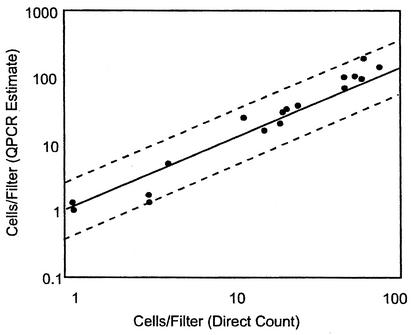

Tests of the method with known numbers of target C. albicans cells from pure culture, as confirmed by solid-phase cytometry, demonstrated a high degree of sensitivity and accuracy in the quantitative measurements (Fig. 2). Extrapolation of the responses for spikes in the range of 1 to 100 cells indicated a mean minimum detection limit (probability of detection, 50%) of 1.2 cells. This was borne out by the low cell count observations, where two of four instances of a single cell on a filter were successfully detected by QPCR. These results also indicate that 95% of the time, the estimate obtained from a single analysis will be ±0.3 logs (i.e., from 50 to 200%) of the true value. When triplicate analyses are utilized, as recommended, the estimate can be expected to range from 67 to 150% of the true value.

FIG. 2.

Experimental sensitivity and accuracy of the CFE and QPCR analysis method for quantifying Candida cells. Known numbers of fluorescently labeled C. albicans cells were collected by filtration on polyethylene terephthalate filters and corroborated by solid-phase cytometry and microscopy. The counted cells on the filters were extracted in the presence of G. candidum reference cells by using the CFE method, and C. albicans cells were quantified by QPCR and ΔΔCT comparative CT analyses. The regression of log cell numbers per filter determined by direct counts on log cell numbers determined by QPCR analysis is represented by a single solid line. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limits for the individual results.

Tap, pond, and river water samples were used to determine the performance of the method for measuring pathogenic Candida species in different backgrounds. The results in Table 4 show that Candida cells can be sensitively and accurately enumerated in 1 liter of tap water by QPCR analysis by using the CFE method with minimal dilution of the DNA extracts and with no additional purification. In contrast, extracts of the pond and river water samples required additional dilution or purification (CFE+Q method) of the DNA extracts to obtain accurate results (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Enumeration of C. albicans cells added to different water samples by QPCR by using different sample preparation methods and extract dilutions

| Sample type | Turbidity (NTU)a | Sample volume (1) | Cells added to sampleb | Extract prep. method | Extract dilution | Measured cells/ samplec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap | 2 | 1 | 90 | CFEd | 1:1 | 163 |

| 20 | 35 | |||||

| 6 | 4 | |||||

| 0 | <1e | |||||

| Tap | 2 | 1 | 90 | CFE+Qf | 1:1 | 123 |

| 20 | 30 | |||||

| 6 | 4 | |||||

| 0 | <1 | |||||

| Pond | 20 | 0.1 | 1,000 | CFE | 1:10 | 1,237 |

| 0 | 2g | |||||

| Pond | 20 | 0.1 | 1,000 | CFE+Q | 1:1 | 692 |

| 0 | 1g | |||||

| River | 200 | 0.02 | 90 | CFE | 1:100 | 93 |

| 20 | 30 | |||||

| 6 | <22 | |||||

| 0 | <37 | |||||

| River | 200 | 0.02 | 90 | CFE+Q | 1:10 | 335 |

| 20 | 32 | |||||

| 6 | 10 | |||||

| 0 | <19 |

NTU, nephelometric turbidity units.

Arithmetic mean for three to five replicate analyses, estimated from solid-phase cytometry.

Geometric mean for three to six replicate samples, estimated from QPCR analysis.

CFE, collection filter extraction.

<, no target detection: CT = 40. Accompanying values are minimum cell detection limits determined by using this CT result, the reference CT results of the test samples, and target and reference CT results of the corresponding calibrator samples in the ΔΔC̄T calculation.

CFE+Q, collection filter extraction with the added step of a Qiagen kit purification.

Presumptive indigenous target organisms in the water sample.

Analysis of Lake Michigan beach samples.

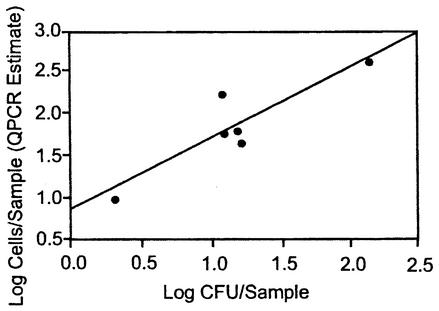

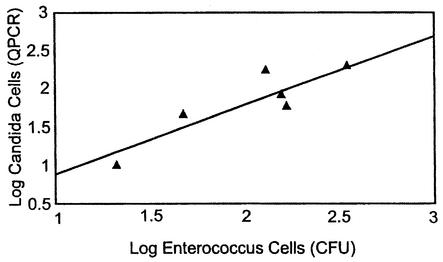

The weekly sampling of the recreational beach water from Lake Michigan showed that the cell quantities of the target organisms were generally low as determined both by QPCR analysis and live culturing (Table 5). As with the previously analyzed surface water samples, it was necessary either to dilute the DNA extracts from the majority of these samples or to subject them to further purification. Estimated cell detection limits, based on G. candidum reference assay results for the different samples and reference and target assay results for the equivalently processed and diluted calibrator samples, ranged from 5 to 40 cells in QPCR assays where no target cells were detected (Table 5). CFU of different target species were obtained in a number of these instances where corresponding QPCR results were negative; however, the quantities of CFU were below the estimated sensitivity range of the QPCR assays in nearly all of these cases. On the other hand, when target cells were detected in the samples by QPCR, they were generally found in substantially higher numbers than by plate counts. As a result, the estimates of total Candida cells across all targeted species for all samples were significantly higher by the QPCR method than by the plates counts (P < 0.01), with a median QPCR-to-CFU ratio of about 5.0. There was a positive correlation (R = 0.91 based on log counts) between the QPCR results for total target Candida and total colony counts of these species (Fig. 3). A positive correlation (R = 0.93) was also seen between the total cell quantities of the target Candida species detected in the QPCR analyses and colony counts of Enterococcus (Fig. 4). PCR amplicons generated by species-specific primer sets from two of the water samples were subjected to nucleotide sequence analyses and in each case showed complete agreement in callable bases with the published sequences of the corresponding target organisms.

TABLE 5.

Cellular enumeration of organisms of six pathogenic Candida species in 100- to 300-ml Lake Michigan beach water samples by culture plate counts coupled with QPCR identification of colonies and by direct QPCR analysisa

| Sample date | Turbidity (NTU) | Analysis method | No. of organisms of the Candida species:

|

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calb | Ckru | Cpar | Cglab | Ctrop | Clus | ||||

| 8/13/01 | 10 | Culture | 9 | 108 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 135 |

| PCRb | 11 | 312 | 38 | 9 | 11 | 40 | 421 | ||

| 8/20/01 | 8 | Culture | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| PCRc | <10d | 61 | <28 | <11 | <8 | <8 | 61 | ||

| 8/27/01 | 19 | Culture | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 16 |

| PCRc | <13 | 46 | <29 | <12 | <8 | <5 | 46 | ||

| 9/04/01 | 23 | Culture | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| PCRc | 13 | 147 | <16 | <7 | 7 | <5 | 167 | ||

| 9/11/01 | 37 | Culture | -e | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PCRf | <13 | 64 | <38 | <15 | 20 | <16 | 84 | ||

| 9/17/01 | 5 | Culture | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| PCRf | <6 | <14 | <20 | <8 | 10 | <5 | 10 | ||

| 9/24/01 | 82 | Culture | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| PCRf | <13 | 62 | <40 | <18 | <12 | <12 | 62 | ||

Mean results from three replicate samples based on 100-ml sample volumes for 9/24/01; all others are based on 300 ml.

Extract prepared with collection filter extraction (CFE); no dilution of extract for analysis.

Extract prepared with collection filter extraction (CFE); 1/10 dilution of extract for analysis.

<, no target detection: CT = 40. Accompanying values are minimum cell detection limits determined by using this CT result, the reference CT results of the test samples, and target and reference CT results of the corresponding calibrator samples in the ΔΔCT method.

-, not determined because of disruption in shipping.

Extract prepared by collection filter extraction plus Qiagen kit purification (CFE+Q); no dilution of extract for analysis.

FIG. 3.

Relationship between cellular enumeration of target Candida species in Lake Michigan beach water samples by culture plate counts (CFU) and by QPCR analysis. Water samples were filtered on nitrocellulose filters for plate counts on BiGGY agar medium, and the resulting CFU of target Candida species were enumerated as described in Table 5 and in the text. Equivalent water sample volumes were filtered through polycarbonate filters, the filters were extracted in the presence of G. candidum reference cells, and the extracts were diluted or further purified as indicated in Table 5. Quantities of each of the six Candida populations were determined by using QPCR assays and ΔΔCT comparative CT analyses. Results are shown for the six water samples indicated in Table 5 for which both methods of analysis were performed and are based on the total cell numbers of the six pathogenic Candida species, as determined by each method for each sample. The regression value for the line is R = 0.91.

FIG. 4.

Relationship between cellular enumeration of Enterococcus species by culture plate counts (CFU) and target Candida species by QPCR analysis. Water samples were filtered on nitrocellulose filters for plate counts on mEI basal medium, and the resulting colonies with blue halos were enumerated as presumptive enterococcal CFU. Results are presented on the basis of a 100-ml water sample volume. Quantities of each of the six Candida populations were determined as described in the legend for Fig. 3, with results presented on the basis of a 300-ml water sample volume. The regression value for the line is R = 0.93.

DISCUSSION

Guiver et al. (16) developed a qualitative clinical method for identifying pathogenic species of Candida based on TaqMan chemistry. However, for environmental analysis of water, it is critical to develop not only specific assays but also highly quantitative and sensitive assays and the method to use them. As described in the present report, this has now been done.

The assays developed in this study target the variable D1/D2 domain of the LSU ribosomal gene and were highly specific when experimentally tested against a wide variety of related and unrelated organisms. The availability of an extensive database of yeast sequences for the LSU target region and associated phylogenetic analyses of these organisms (24) also allowed testing of the primers by computer analysis against closely related species for which no cultures were available and further supports our confidence in the specificity of these assays.

As implied by the extrapolation results in Table 3 and demonstrated by the experimental results in Fig. 2, the method provides sensitivities of detection approaching one cell per filter for pure cultures with no PCR inhibitors present. Results from Table 4 suggest that a similar level of sensitivity can be expected for the analyses of 1-liter tap water samples by this method, which will be critical for the analysis of drinking water, as opposed to clinical samples, where high populations would typically be found. Our results further indicate that the accuracy of the method provides a 95% confidence range from 50 to 200% of the true value in such relatively PCR inhibitor-free water samples.

Results from Tables 4 and 5, not surprisingly, suggest that the sensitivity of the method decreases roughly in proportion to the extent to which DNA extracts from various surface water samples must be diluted to overcome PCR inhibition. The suspended solid content (turbidity) of these water samples largely dictated the volumes that could be filtered and hence analyzed at one time. For most samples, either no dilution or a tenfold dilution of the DNA extract was sufficient for analysis. Some samples, generally those of higher turbidity (e.g., the river water sample in Table 4), required 100-fold dilution or additional purification of the extract. We further observed that purification of the DNA extracts could result in an almost tenfold loss of DNA in some instances, as demonstrated by increases in both the target and reference assay CT values from calibrator extracts following this procedure. Such variations in DNA recovery will also affect the method's sensitivity. As a consequence, the sensitivity of this method can vary appreciably with different surface water samples and in some instances may not be as great as by culturing. Nevertheless, a strong correlation was observed between total plate counts of the target species and total numbers of these organisms as determined by QPCR analysis in this study. Also of interest was the observation that the QPCR method gave significantly higher overall estimates of target cell numbers than the plating method across all samples and species. Further studies will be needed to determine whether this observation can be attributed to low culturability of these organisms from the environment or possibly to their heterogeneous distribution in the water as the result of cell clumping or their occurrence in multicellular structures. While PCR template contamination of the extracts could also potentially contribute to these results, negative controls in these experiments consistently gave no signals in parallel analyses.

The QPCR method may be highly useful for detecting pathogenic Candida in both potable and surface waters as these and other fungi become more of a nosocomial and environmental risk. It has been known for many years that yeasts like Candida occur in drinking water (4, 7, 8). Rosenzweig et al. (30, 31) showed that various fungi, including yeasts, were relatively resistant to chlorine inactivation and survived conventional water treatment. This survival can lead to their accumulation in distribution systems. For example, densities of C. parapsilosis ranged from 3.1 to 4.6 CFU/cm2 of surface area in the Springfield, Mo., water distribution system (12). Preliminary results from our laboratory with a fluorescently labeled C. albicans antibody and solid-phase cytometry have suggested the presence of pathogenic Candida species in U.S. tap water (N. E. Brinkman, R. A. Haugland, J. W. Santo Domingo, and S. J. Vesper, Abstr. 101st Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2001, abstr. Q-417, p. 669).

Candida has also been isolated from drinking water outside the U. S. In France, 50% of samples were contaminated with yeasts, with Candida being most common (22). In Finland, 38 samples of chlorinated drinking water were examined. Yeasts, mostly Candida species, occurred in 50% of the samples (27). In Greece, Candida species were isolated from the hospital water supply and from hemodialysis units (2, 3).

Recreational waters may also pose a threat to human health from candidiasis (13, 14). Candida species are frequently isolated from human-impacted surface water and sewage (11, 40). Bergen and Wagner-Merner (5) isolated Candida spp. from beaches in Tampa Bay, Fla. A study in the 1970s of the river water entering Lake Michigan just west of Mount Baldy recreational beach showed that C. krusei was the most numerous Candida species (40). Our results show that C. krusei is still the most numerous of the pathogenic yeast in this environment. Besides the direct analysis of pathogenic Candida like C. krusei, this technology may also be useful as a method to monitor fecal pollution and changing populations.

Bacterial indicators of fecal pollution are sometimes confounded because of source tracking issues. Quantification of Candida may provide an alternative or additional indicator of fecal pollution. Another use might be as an early warning system for change in a water supply by comparing ratios of Enterococcus to Candida populations over time. Also, as the occurrence of drug-resistant yeasts increases, the monitoring of the changes in yeast populations of fecal origin may become important.

A significant advantage of QPCR technology over culturing lies in its combination of speed and accuracy. Sample processing can be completed within approximately to 30 to 90 min, depending on whether the CFE or CFE+Q sample extraction method is used, and sample analysis times can range from approximately 30 min to 2 h, depending on the choice of thermal cycling instrument (10). This is opposed to the 48 h required for culturing methods. In cases like a bathing beach, significant spikes of pathogenic Candida species resulting from untreated effluents or storm runoff could be quickly detected. This method for the analysis of surface water could be used as a practical tool for rapid, same-day communication for risk assessment and possible use for beach closure deliberations. Protection of drinking water supplies also requires timely and specific information about the species and quantities of microbial pathogens, which this technology can provide.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an appointment (N.E.B.) to the Postgraduate Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. DOE and the U.S. EPA.

We thank Dawn Shively (USGS) for technical help and sample collection. We also thank Teresa Ruby for the preparation of the figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society for Testing and Materials. 1987. Standard test method for enumeration of Candida albicans in water, p. 113-118. In ASTM standards on materials and environmental microbiology, 1st ed. American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadephia, Pa.

- 2.Arvanitidou, M., K. Kanellou, T. C. Constantinides, and V. Katsouyannopoulos. 1999. The occurrence of fungi in hospital and community potable waters. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29:81-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitidou, M., S. Spaia, A. Velegraki, M Pazarloglou, D. Kanetidis, P. Pangidis, N. Askepidis, C. Katsinas, G. Vayonas, and V. Katsouyannopoulos. 2000. High level of recovery of fungi from water and dialysate in haemodialysis units. J. Hosp. Infect. 45:225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bays, L. R., N. P. Burman, and W. M. Lewis. 1970. Taste and odor in water supplies in Great Britain: a survey of the present position and problems for the future. Water Treat. Exam. 19:13-160. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergen, L., and D. T. Wagner-Merner. 1977. Comparative survey of fungi and potential pathogenic fungi from selected beaches in the Tampa Bay area. Mycologia 69:299-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Best, V., L. Yu, J. Stout, A. Goetz, R. R. Muder, and F. Taylor. 1983. Legionellaceae in the hospital water supply. Epidemiological link with disease and evaluation of a method for control of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease and Pittsburgh pneumonia. Lancet ii:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman, N. P. 1965. Taste and odor due to stagnation and local warming in long lengths of piping. Proc. Soc. Water Treat. Exam. 14:125-131. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burman, N. P., C. W. Oliver, and J. K. Stevens. 1969. Membrane filtration technique for the isolation from water of coli-arogens, Escherichia coli, faecal streptococci. Clostridium perfringens, actinomycetes, and microfungi, p. 127-134. In D. A. Sharpton and G. W. Gould (ed.), Isolation methods for microbiologists, No. 3. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Chang, H. C., S. N. Leaw, A. H. Huang, T. L. Wu, and T. C. Chang. 2001. Rapid identification of yeasts in positive blood cultures by a multiplex PCR method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3466-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockerill, F. R., III, and T. F. Smith. 2002. Rapid-cycle real-time PCR: a revolution for clinical microbiology. ASM News 68:77-83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook, W. L., and R. L. Schlitzer. 1981. Isolation of Candida albicans from freshwater and sewage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:840-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doggett, M. S. 2000. Characterization of fungal biofilms within a municipal water distribution system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1249-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efstratiou, M. A., A. Mavridou, S. C. Richardson, and J. A. Papdakis. 1998. Correlation of bacterial indicator organisms with Salmolnella spp., Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans in sea water. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26:342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falcao, D. P., C. Q. F. Leite, M. J. S. Simoes, M. J. S. M. Giannini, and S. R. Valentini. 1993. Microbial quality of recreational waters in Araraquara, SP, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 128:37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg, A. E., L. S. Clesceri, and A. D. Eaton (ed.). 1998. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 20th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Guiver, M., K. Levi, and B. A. Oppenheim. 2001. Rapid identification of Candida species by TaqMan PCR. J. Clin. Pathol. 54:362-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagler, A. N., and L. C. M. Hagler. 1978. The yeasts of fresh water and sewage. An. Microbiol. (Rio J.) 23:79-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haugland, R. A., and J. L. Heckman. 1998. Identification of putative sequence specific PCR primers for detection of the toxigenic fungal species Stachybotrys chartarum. Mol. Cell. Probes 12:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haugland, R. A., S. J. Vesper, and L. J. Wymer. 1999. Quantitative measurement of Stachybotrys chartarum conidia using real time detection of PCR products with the TaqMan fluorogenic probe system. Mol. Cell. Probes 13:329-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haugland, R. A., N. E. Brinkman, and S. J. Vesper. 2002. Evaluation of rapid DNA extraction methods for the quantitative detection of fungal cells using real time PCR analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heid, C., J. Stevens, K. Livak, and P. Williams. 1996. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 6:986-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinzelin, F., and J. C. Block. 1985. Yeasts and filamentous fungi in drinking water. Environ. Tech. Lett. 6:101-106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurley, R., J. de Louvois, and A. Mulhall. 1987. Yeasts as human and animal pathogens, p. 207-281. In D. A. H. Rose and J. S. Harrison (ed.), The yeasts, vol. 1, 2nd ed. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Kurtzman, C. P., and C. J. Robnett. 1998. Identification and phylogeny of ascomycetous yeasts from analysis of nuclear large subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA partial sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:331-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannarelli, B. M., and C. P. Kurtzman. 1998. Rapid identification of Candida albicans and other human pathogenic yeasts by using short oligonucleotides in a PCR. 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1634-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, C., D. Roberts, M. van der Weide, R. Rossau, G. Jannes, T. Smith, and M. Maher. 2000. Development of a PCR-based line probe assay for identification of fungal pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3735-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niemi, R. M., S. Knuth, and K. Lundstrom. 1982. Actinomycetes and fungi in surface waters and in potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:378-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiss, E., K. Tanaka, G. Bruker, V. Chazalet, D. Coleman, J. P. Debeaupuis, S. Hanazawa, J. P. Latge, J. Lortholary, K. Makimura, C. J. Morrison, S. Y. Murayama, S. Naoe, S. Paris, J. Sarfati, K. Shibuya, D. Sullivan, K. Uchida, and H. Yamaguchi. 1998. Molecular diagnosis and epidemiology of fungal infections. Med. Mycol. 36(Suppl. 1):249-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roe, J., R. A. Haugland, S. J. Vesper, and L. J. Wymer. 2001. Quantification of Stachybotrys chartarum conidia in indoor dust using real time, fluorescent probe-based detection of PCR products. J. Expos. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 11:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenzweig, W. D., H. Minnigh, and W. O. Pipes. 1983. Chlorine demand and inactivation of fungal propagules. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:182-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenzweig, W. D., H. Minnigh, and W. O. Pipes. 1986. Fungi in potable water distribution systems. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 78:53-55.

- 32.Sandu, G. S., B. C. Kline, L. Stockman, and G. D. Roberts. 1995. Molecular probes for diagnosis of fungal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2913-2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer, J. F. T., and D. M. Spencer. 1997. Ecology: where yeasts are, p. 48-58. In J. F. T. Spencer and D. M. Spencer (ed.). Yeasts in natural and artificial habitats. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany.

- 34.Stultz, J. R., O. Snoeyenbos-West, B. Methe, D. R. Lovley, and D. P. Chandler. 2001. Application of the 5′ fluorogenic exonuclease assay (TaqMan) for quantitative ribosomal DNA and rRNA analysis in sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2781-2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki, M. T., L. T. Taylor, and E. F. DeLong. 2000. Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes in mixed microbial populations via 5′-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4605-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takai, K., and K. Horikoshi. 2000. Rapid detection and quantification of members of the archaeal community by quantitative PCR using fluorogenic probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5066-5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1997. Method 1600: membrane filter test methods for enterococci in water. [EPA-821/R-97/004.] Office of Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

- 38.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Improved enumeration methods for the recreational water quality indicators: enterococci and Escherichia coli. [EPA-821./R-97/004.] Office of Science and Technology, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

- 39.Widjojoatmodjo, M. N., A. Borst, R. A. F. Schukkink, A. T. A. Box, N. M. M. Tacken, B. Van Gemen, J. Verhoef, B. Top, and A. C. Fluit. 1999. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) detection of medically important Candida species. J. Microbiol. Methods 38:81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woollett, L. L., and L. R. Hendrick. 1970. Ecology of yeasts in polluted water. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 36:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]