Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis EJ97 produces a cationic bacteriocin (enterocin EJ97) of low molecular mass (5,327.7 Da). The complete amino acid sequence of enterocin EJ97 was elucidated after automated microsequencing of oligopeptides generated by endoproteinase GluC digestion and cyanogen bromide treatment. Transfer of the 60-kb conjugative plasmid pEJ97 from the bacteriocinogenic strain E. faecalis EJ97 to E. faecalis OG1X conferred bacteriocin production and resistance on the recipient. The genetic determinants of enterocin EJ97 were located in an 11.3-kb EcoRI-BglII DNA fragment of pEJ97. This region was cloned and sequenced. It contains the ej97A structural gene plus three open reading frames (ORFs) (ej97B, ej97C, and ej97D) and three putative ORFs transcribed in the opposite direction (orfA, orfB, and orfC). The gene ej97A translated as a 44-amino-acid residue mature protein lacking a leader peptide with no homology to other bacteriocins described so far. The product of ej97B (Ej97B) shows strong homology in its C-terminal domain to the superfamily of bacterial ATP-binding cassette transporters. The products of ej97C (Ej97C) and ej97D (Ej97D) could be proteins with 71 and 64 residues, respectively, of unknown functions and with no significant similarity to known proteins. There are two additional ORFs (ORF1 and ORF6) flanking the ej97 module, which have been identified as a transposon-like structure (tnp). ORF1 shows similarities to transposase of the Lactococcus lactis element ISS1 and is up to 50% identical to IS1216. This is flanked by two 18-bp inverted repeats (IRs) that are almost identical to those of ISS1 and IS1216. ORF6 (resEJ97) shows strong homology to the resolvase of plasmid pAM373 and up to 40 to 50% homology with the recombinase of several multiresistant plasmids and transposons from Staphylococcus aureus and E. faecalis. These data suggest that EJ97 could represent a new class of bacteriocins with a novel secretion mechanism and that the whole structure could be a composite transposon. Furthermore, two additional gene clusters were found: one cluster is probably related to the region responsible for the replication of plasmid pEJ97, and the second cluster is related to the sex pheromone response. These regions showed a high homology to the corresponding regions of the conjugative plasmids pAM373, pPD1, and pAD1 of E. faecalis, suggesting that they have a common origin.

Many gram-positive bacteria secrete antimicrobial substances of ribosomal synthesis known as bacteriocins (13, 16, 27, 58). Among them, the best studied microbial group is the lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Lactococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Leuconostoc, in which many bacteriocins have been characterized at the biochemical and genetic level in recent years (18, 27, 34, 37). LAB bacteriocins have become attractive as natural food preservatives. In general, they are small cationic peptides that are hydrophobic and very stable to heat and pH extremes. They can be grouped into at least three or four classes (28, 37), although other classifications have also been proposed (58). Class I comprises lantibiotics, which are small membrane-active peptides containing modified amino acid residues, like lanthionine; class II includes the small heat-stable non-lantibiotics, which are divided into subgroups IIa (Listeria-active peptides of the pediocin family, with a YGNGVXC consensus sequence), IIb (bacteriocins whose activity depends on the complementary activities of two peptides), and IIc (which is uncertain and has been suggested to include thiol-activated and sec-dependent secreted bacteriocins); class III includes large heat-labile bacteriocins; and class IV is claimed to consist of peptides that require other constituents for their activity (lipids and carbohydrates). However, this classification probably needs to be widened to include other peptides that cannot be properly placed in any of the other groups, such as enterocins L50A and L50B (11) and enterocin Q (12), which are devoid of leader peptides; lactococcin 972, a new bacteriocin that inhibits septum formation in lactococci (30); and the cyclic peptide enterocin AS-48, produced by Enterococcus faecalis (31, 32). Since many of these inhibitory substances are likely to meet the GRAS (generally recognized as safe) status, their use as natural food preservatives has also been widely investigated and discussed (13, 17, 46).

Bacteriocins from fecal enterococci have received much less attention. Nevertheless, interest in them has been renewed because enterococci are natural inhabitants of the intestine and many of them may be able to produce antimicrobial substances, which may play an important role in governing the complex microbial interactions taking place within the gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, enterococci are frequently found in fermented foods, and many of the bacteriocins produced are active against food-borne pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes (26, 33) and Bacillus cereus (1). To date, only a few bacteriocins from E. faecalis have been characterized at the biochemical and genetic levels. Among these are the hemolysin-bacteriocin (which is also classified as a lantibiotic) encoded on the 58-kbp conjugative plasmid pAD1 (25); bacteriocin 31, an antilisterial bacteriocin encoded on the 57.5-kbp plasmid pYI17 (57); the cyclic peptide enterocin AS-48, encoded on the 60-kbp plasmid pMB2 (31); and enterocins 1071A and 1071B, two antimicrobial peptides produced by E. faecalis BFE 1071, which show homology to the α and β peptides of lactococcin G (4, 20).

Enterocin EJ97 is a low-molecular-mass (5,340 Da) cationic peptide produced by E. faecalis EJ97. It is active on gram-positive bacteria, including enterococci and species of Bacillus, Listeria, and Staphylococcus (22). This bacteriocin has been purified and characterized previously, and its N-terminal sequence has been elucidated up to residue 18 (22). In this report, we present a study of the protein sequence of EJ97 and the genetic characterization of the region harboring the EJ97 gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

E. faecalis EJ97 was isolated from municipal wastewater (22). E. faecalis OG1X was obtained from D. B. Clewell (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, School of Medicine, University of Michigan). All enterococcal strains were grown at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and maintained as frozen stocks at −20°C in BHI containing 20% glycerol. Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) served as the host of the recombinant plasmids and was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium with vigorous shaking.

Bacteriocin purification and amino acid sequencing.

Enterocin EJ97 was purified from E. faecalis EJ97 stationary-phase culture supernatants as previously described (22). The bacteriocin protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (9). After purification, 50 μg of EJ97 protein was digested with endoproteinase GluC from Staphylococcus aureus strain V8 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 4 h at 37°C, at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:40. The same amount of bacteriocin was hydrolyzed with cyanogen bromide (Sigma Chemical Co., Madrid, Spain) as described elsewhere (14). The resulting peptides were separated by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a Vydac C18 column (4.6 by 25 mm; The Separation Group, Hesperia, Calif.) equilibrated in solvent A (10 mM trifluoroacetic acid in Milli Q water). The material retained in the column was eluted with a linear gradient (0 to 100% over 30 min) of solvent B (4 mM trifluoroacetic acid in 2-propanol-acetonitrile [2/1 by volume]) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions collected from the effluent were lyophilized in a Speedvac concentrator (Savant).

Automated N-terminal sequencing of peptides was performed on a Procise protein sequencer (model 494; Applied Biosystems). Samples were analyzed in a flowthrough reactor bound to a fiberglass filter preconditioned with Bioprene Plus.

Mass determination of the peptides was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry under conditions described elsewhere (22).

Conjugal transfer of the enterocin EJ97 trait.

The strain E. faecalis EJ97 (Sms) was used as a donor in mating experiments with the plasmid-free strain E. faecalis OG1X (Smr) by the filter method as described elsewhere (43). Transconjugants were selected on BHI agar plates containing streptomycin (final concentration, 500 μg/ml) and tested for the ability to produce bacteriocin. E. faecalis OG1X served as the indicator strain.

DNA isolation, cloning, and transformation.

Plasmid DNA from E. faecalis was isolated as described by Anderson and McKay (3). Plasmids were isolated from E. coli by the alkaline lysis method (49). Large-scale plasmid DNA preparations were purified using a Flexiprep kit (Amersham Biosciences). Restriction fragments of the desired size for cloning were separated on 0.7% agarose gels, isolated, and purified with Sephaglass (Amersham Biosciences). Plasmid pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega Life Sciences) was used for cloning experiments. E. coli DH5α cells were transformed using the CaCl2 procedure (49). Transformants containing recombinant plasmids derived from pGEM-3Zf(+) were selected on Luria-Bertani agar plates containing ampicillin (final concentration 50 μg/ml). General procedures for cloning and DNA manipulations were essentially as described elsewhere (49).

Nucleic acid hybridizations and nucleotide sequencing.

Two degenerate oligodeoxynucleotide probes corresponding to the N- and C-terminal peptide sequences of EJ97 were synthesized and labeled at the 3′ end with digoxigenin-11-ddUTP by using terminal transferase, as specified by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). PCR was performed on 100-μl samples containing E. faecalis EJ97 plasmid DNA (1.5 μg), the primers (1 pM each), the deoxynucleoside triphosphates (200 μM each), and Taq DNA polymerase (2.5 U). The buffer was 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) containing 50 mM KCl and 1.5 mM MgCl2. Samples were covered with mineral oil and subjected to 30 amplification cycles of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1.5 min of annealing at 55°C, and 1 min of polymerization at 72°C. The 120-bp DNA PCR product was partially sequenced, and the sequence obtained translated exactly into the expected peptide segment. From this nucleotide sequence, new nondegenerate probes were synthesized, labeled at the 3′ end with digoxigenin-11-ddUTP, and used to screen gene libraries by hybridization. Southern blotting was performed by transfer of restriction endonuclease-digested pEJ97 plasmid on 0.7% agarose gels to nylon membranes. Hybridization and detection of the probes were carried out as specified by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Nucleotide sequencing by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method was carried out with restriction fragments cloned into pGEM-3Zf(+) by using universal, reverse, and synthetic primers. DNA sequences were compiled with the MAP program from the Genetics Computer Group package. The GenBank, EMBL, translated GenBank, and National Biomedical Research Foundation sequence data banks were searched for similar DNA or amino acid sequences by using the FASTA and TFASTA programs.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA of E. faecalis EJ97 was isolated as described by Martínez-Bueno et al. (32) and separated electrophoretically in a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel (10 μg/lane). RNA was transferred by capillary blotting onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N+; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) overnight and fixed by UV illumination for 3 min. The filters were incubated overnight at 50°C in a high-sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer at pH 7.0 (7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 2% blocking reagent, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine) containing 100 ng of specific probes. The probe used in the Northern blot experiments was labeled in a thermocycling reaction using the deoxynucleoside triphosphate-labeling mix of a DIG-DNA labeling and detection kit obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals as specified by the manufacturer. A gel lane was cut off and stained with ethidium bromide, and the rRNAs were used as the molecular weight standard.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to the EMBL Data Library and given accession number AJ490170.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Amino acid sequence of enterocin EJ97.

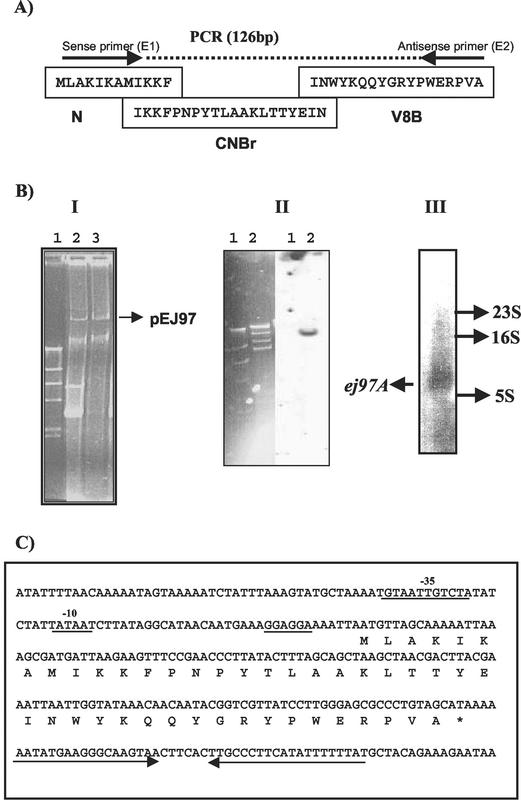

Two peptides (V8A and V8B) from endoproteinase GluC digestion of EJ97 protein were sequenced (Table 1). The amino acid sequence obtained for peptide A was identical to the N-terminal sequence of EJ97 described previously (22). Peptide B (Table 1; V8B in Fig. 1A) contained 18 amino acid residues. Cyanogen bromide digestion of EJ97 yielded a large peptide fragment whose N-terminal sequence overlapped by 10 residues with the N-terminal sequence of the bacteriocin known previously (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the last two residues of this fragment were identical to the first two residues of peptide V8B. A glutamic acid residue at position 18 in the cyanogen bromide fragment indicated a proteolytic site for generation of V8B peptide.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequence determinations for intact enterocin EJ97 and peptide fragments from protease V8 and cyanogen bromide digestion

| Peptide | Amino acid sequence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Native protein | MLAKIKAMIKKFPNPYTL | None |

| V8A | MLAKIKAMIKKFPNP | Protease V8 digestion |

| V8B | INWYKQQYGRYPWERPVA | Protease V8 digestion |

| C | IKKFPNPYTLAAKLTTYEIN | CNBr cleavage |

FIG. 1.

(A) Complete amino acid sequence of enterocin EJ97, deduced after linking the previously published N-terminal sequence (N) with the sequences obtained after cyanogen bromide digestion (CNBr) and protease V8 digestion (V8A and V8B). Oligonucleotide probes E1 (sense primer, 5′-ATGATHAARAARTTYCCNAAYCC-3′) and E2 (antisense primer, 5′-GCNACNGGNCKYTCCCANGGRTA-3′) derived from the N- and C-terminal peptide sequence are shown. (B) Panel I: λ-HindIII (lane 1), plasmid profile of the wild-type strain E. faecalis EJ97 (lane 2), and plasmid profile of the transconjugant E. faecalis OG1X producing enterocin EJ97 (lane 3). The plasmid acquired by the transconjugant(pEJ97) is shown. Panel II: λ-HindIII (lane 1); BglII digestion of plasmid pEJ97 and identification of the 14-kb DNA fragment carrying the ej97A structural gene by hybridization with a oligonucleotide probe derived from the EJ97 peptide sequence (lane 2). Panel III: Northern blot of total RNA (10 μg) from E. faecalis EJ97 after hybridization with a probe derived from ej97A. The arrow indicates a 0.2-kb fragment. (C) DNA region and deduced amino acid sequence of the enterocin EJ97 gene from E. faecalis EJ97. The presumptive −10 and −35 promoter sequences and the RBS are underlined. The inverted repeats downstream of ej97A, which might act as a rho- independent transcriptional terminator, are indicated by reversed arrows.

The amino acid sequence obtained after superposition of the different peptide sequences corresponded to a protein of 44 amino acid residues and a deduced molecular mass of 5,322.3 Da (Fig. 1A). This value was very similar to that obtained by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the intact bacteriocin protein (5,327.7 Da), strongly suggesting that the deduced amino acid sequence corresponds to the protein sequence of enterocin EJ97.

A conjugative plasmid is responsible for EJ97 production and immunity.

Results from hybridization with DNA probes derived from the EJ97 protein sequence indicated that the 60-kb plasmid pEJ97 from E. faecalis EJ97 could carry the information required for EJ97 production (data not shown). To confirm the location of the bacteriocin character (production and immunity) within pEJ97, this plasmid was transferred by conjugation from E. faecalis EJ97 (Sms) into the plasmid-free strain E. faecalis OG1X (Smr, Bac−). The transconjugants were selected on plates containing 500 μg of streptomycin per ml and tested for bacteriocin production. All the bacteriocinogenic transconjugants isolated harbored a 60-kb plasmid. One of these transformants was used for further characterization by hybridization and endonuclease digestion experiments and as source of the transferred plasmid, which was identified as pEJ97 (Fig 1B, panel I).

To ensure that the inhibitory activity detected in OG1X(pEJ97) transconjugants was due to the production of enterocin EJ97, the transconjugants were tested for crossed immunity with the wild-type strain E. faecalis EJ97. The reciprocal resistance detected for the two strains suggested that they produced the same bacteriocin. Moreover, purification of the bacteriocin from transconjugants by the procedure originally described elsewhere (22) indicated the presence of a peptide with an identical retention time on reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography to that of enterocin EJ97 (results not shown). Furthermore, the spectrum of antimicrobial activity recorded for the peptide isolated from the transconjugant OG1X(pEJ97) was identical to that recorded for E. faecalis EJ97. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that plasmid pEJ97 carries the genetic determinants of enterocin EJ97 (production and immunity). In addition, the E. faecalis OG1X(pEJ97) transconjugants aggregated in broth, probably due to the constitutive expression of sex pheromone genes harbored by this plasmid. Similar results were described when the cPD1 pheromone-responding bacteriocinogenic plasmid pMB2 was introduced into E. faecalis OG1X (41).

Identification of the structural gene ej97A.

Two degenerate oligonucleotides were synthesized from the amino acid sequence of enterocin EJ97 (Fig. 1A). Oligonucleotide E1 (sense primer) coded for the N-terminal sequence of enterocin EJ97, and oligonucleotide E2 (antisense primer) coded for the C-terminal sequence. PCR amplification with both oligonucleotides as primers and the E. faecalis EJ97 DNA as template generated a 132-bp DNA segment whose sequence translated into a 44-amino-acid residue product identical to the primary structure of EJ97 obtained by Edman degradation (Fig. 1A).

The structural gene ej97A was located in a 14-kb BglII fragment of pEJ97 after hybridization with DNA probes derived from the EJ97 protein sequence (Fig. 1B, panel II). This fragment was cloned in plasmid pGEM-3Zf, previously cut with BamHI and dephosphorylated. The new recombinant plasmid (named pGEM-57) was characterized by endonuclease restriction mapping, Southern blotting with synthetic labeled probes, and DNA sequencing. The DNA sequence from the structural gene ej97A revealed a 132-nucleotide open reading frame (ORF) that encoded 44 amino acid residues, corresponding to the primary structure of enterocin EJ97 (Fig. 1C). This ORF starts with an ATG codon and terminates with a TAA codon. The 5′-GGAGGAA-3′ segment at positions −6 to −12 upstream of the translation start codon resembles a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence. Since the 132-nucleotide residue is directly translated into a 44-amino-acid mature protein, this bacteriocin lacks a leader peptide sequence. This peculiar feature is also found in enterocins L50A and L50B (11) and enterocin Q (12). A search of protein sequence databases revealed no polypeptides with homology to enterocin EJ97. Similarly to most of the bacteriocins described so far, the hydrophobicity plot of enterocin EJ97 indicates that it is a hydrophobic peptide containing up to 48% hydrophobic amino acid residues. It is also quite basic, with a predicted pI of 10.8. Downstream of ej97A there is an inverted repeat that could form a stem-loop structure, representing a possible rho-independent transcriptional terminator. The presence of possible terminator sequences downstream of ej97A may imply that the bacteriocin structural gene is a transcriptional unit. To confirm this fact, the expression of the ej97A gene was studied by Northern blot analysis, using total RNA from E. faecalis EJ97. Hybridization with a probe derived from ej97A revealed a small band of hybridization (approximately 0.2 kb) (Fig. 1B, panel III), which corresponded to the expected size of the mRNA for the ej97A gene. These data strongly suggest that the structural gene of enterocin EJ97is a transcriptional unit.

Analysis of ORFs found upstream and downstream of ej97A gene.

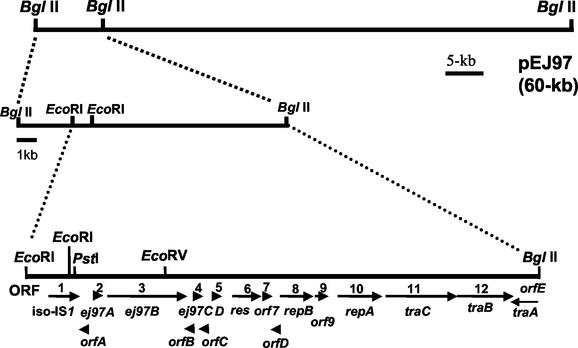

The DNA sequence of a 11.3-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment of pGEM-57, which carries the structural gene ej97A, was determined after being cloned in pGEM-3Zf(+) (Fig. 2). Computer analysis of the DNA sequence revealed 17 probable ORFs: 12 of them (numbered ORF1 to ORF12) were transcribed in the same direction as ej97A (ORF2), and 5 (named ORFA to ORFE) were transcribed in the opposite direction. The translation start point for each ORF was tentatively located by several criteria: (i) the overall distribution of the AT content in the third position of the codons, (ii) the codon usage within the putative coding sequences, (iii) the observed similarities between the putative ORF product and those of other genes in the databases, and (iv) the presence of a canonical ribosome- binding site (RBS) at a suitable distance from the putative translation start codon. These are indicated on the map in Fig. 2. The first G of the first EcoRI site (GAATTC) is designated as nucleotide 1. The ORFs are listed in Table 2 with several annotations. Database comparisons indicated four clusters of genes, some of which correspond to homologues of genes on the pheromone-responding enterococcal plasmids pAD1, pPD1, and pAM373, as well as conserved or hypothetical proteins in Lactoccocus and Streptococcus spp.: (i) the enterocin EJ97 region, (ii) a putative transposase-resolvase module, (iii) genes involved in plasmid replication, and (iv) genes related to the sex pheromone response (Fig. 2; Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Physical and genetic map of the EcoRI-BglII DNA fragment (11.3 kb) from plasmid pEJ97. Horizontal arrows indicate ORFs on plasmid pGEM-57 and the direction of transcription. Four different DNA regions could be found: the DNA region carrying the genes involved in enterocin EJ97 production (ORF2 to ORF4 and putative ORFA to ORFC), a transposase-resolvase module (ORF1 and ORF6), the putative region involved in plasmid DNA replication (ORF7 to ORF11 and the putative ORFD), and a partial DNA fragment related to the sex pheromone response (ORF11, ORF12, and ORFE). Putative ORFs identified in the sequenced fragment are indicated.

TABLE 2.

ORFs identified in the 11.3-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment from plasmid pEJ97 cloned in pGEM-3Zf(+)

| ORF | Genea | No. of amino acids in product | Nucleotide at:

|

Identity or homology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||

| ORF1 | orf1 | 229 | 510 | 1199 | Transposase of iso-IS S1 element |

| ORF2 | ej97A | 44 | 1581 | 1715 | Structural gene for enterocin EJ97 |

| ORF3 | ej97B | 583 | 1796 | 3547 | ABC transporter |

| ORF4 | ej97C | 66 | 3604 | 3804 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORF5 | ej97D | 64 | 4098 | 4292 | Hypothetical protein in Lactococcus |

| ORF6 | resEJ97 | 213 | 4452 | 5093 | Resolvase of pAM373 (orf21) (15) |

| ORF7 | orf7 | 68 | 5145 | 5351 | uvrC of pAD1 (38) and orf21 of pAM373 (15) |

| ORF8 | repB | 284 | 5441 | 6238 | ParA family (6); RepB from pAD1 (59) |

| ORF9 | orf9 | 98 | 6241 | 6537 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORF10 | repA | 317 | 6874 | 7857 | RepA from pAD1 (59) |

| ORF11 | traC | 545 | 7877 | 9514 | TraC from pPD1 (35) |

| ORF12 | traB | 414 | 9525 | 10679 | TraB from pPD1 (35) |

| ORFA | orfA | 50 | −1445 | −1293 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORFB | orfB | 70 | −3788 | −3576 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORFC | orfC | 38 | −3933 | −3817 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORFD | orfD | 71 | −5550 | −5335 | Hypothetical protein |

| ORFE | traA | NDb | ND | −10741 | TraA from pPD1 (35) |

According to experimental data or homology to data banks.

ND, not determined.

(i) Enterocin EJ97 region.

Besides the structural gene ej97A (corresponding to ORF2), we found several ORFs that could be related to the bacteriocinogenic character (production and secretion of and immunity to enterocin EJ97) (Fig. 2; Table 2). The third ORF (ej97B) was found only 82 nucleotides downstream of ej97A, and it was preceded by a putative SD sequence (AGGAGGA). This ORF spans 1,752 bp and encodes a 583-amino-acid protein with homologies to the superfamily of bacterial ATP-dependent transport proteins, also known as ABC transporters (19). Analysis of the primary sequence of this polypeptide (Ej97B) revealed extensive hydrophobic stretches (residues 1 to 300) that were able to form six putative transmembrane domains. Results obtained by FASTA confirm the existence of the two ATP-binding motif sequences GPSGAGKTTIFDL (residues 375 to 387) and RAFLNPTFIIADEVT (residues 492 to 506) corresponding to the Walker A and B motifs found in ABC transporters. Moreover, the B site was immediately preceded by a highly conserved sequence, the C motif (LSGGEKQR), where the Glu is not a conservative change in relation to the first Gln of the signature sequence LSGGQ(RK)QR (51). Most of the bacteriocin operons described to date encode ABC transport proteins that are involved in both secretion and maturation processes (28, 37), as well as in bacteriocin resistance in some cases, such as the ABC transport proteins of mersacidin (2), mutacin II (10), subtilin (29), enterocin AS-48 (32), nisin (52), and lacticin 481 (44).

The deduced ORF4 (ej97C) was located 55 nucleotides downstream of ej97B, and it was also preceded by a putative SD sequence (GGAGG). The predicted product should be a basic and strongly hydrophobic protein, with 71 amino acid residues. ORF5 (ej97D) was found 508 nucleotides downstream of ej97C. A putative SD sequence (AGGATGA) was identified upstream. This ORF spans 192 nucleotides and encodes a basic and hydrophobic protein with 64 amino acid residues. Database comparisons indicate that the putative Ej97C and Ej97D are hypothetical proteins of unknown function. Probably, they could act as accessory factors related to the secretory machinery of enterocin EJ97 along with the ABC transporter Ej97B. Furthermore, they could also be involved in bacteriocin immunity.

We also found three small ORFs (ORFA to ORFC) which are transcribed in the opposite direction to ej97A. ORFA (orfA) is located 144 nucleotides upstream of ej97A, spanning 153 nucleotides, and it could encode a 51-amino-acid residue protein with a predicted molecular mass of 5.3 kDa. A putative SD sequence (GAAAG) was located upstream of orfA. The products of orfB (ORFB) and orfC (ORFC) could encode hypothetical proteins with 70 and 38 amino acids residues, respectively (Table 2). However, we did not detect SD consensus sequences upstream of either ORF, and their predicted products did not show homologies to other proteins. Therefore, these two ORFs should be considered only putative.

(ii) Putative transposase-resolvase module, present immediately upstream and downstream of the ej97 genes.

The EJ97 region (ej97ABCD, and probably the putative orfA) is located between two sequences which may correspond to a transposon-like structure, ORF1 and ORF6 (Fig. 2; Table 2). orf1 potentially codes for a 229-residue protein that shows similarities to the putative transposase of the L. lactis element ISS1 (40, 47) and is 50% identical to the transposase of IS1216, an insertion sequence found in Enterococcus hirae (42) and some transposons from E. faecalis (Tn916 and Tn917). These elements are plasmid borne, although some IS1216 modules also seem to be present on the chromosome. The enterococcal IS1216 and the S. aureus IS257 are highly similar and belong to the ISS1 family (47). Moreover, ORF1 is flanked by two 18-bp inverted repeats that are almost identical (94%) to those of ISS1 and IS1216, except for a mismatch at position 5 (a T instead of a C): left terminal repeat, nucleotides 420 to 437, is AAAAGAGCTGGGTTTTGT; right terminal repeat, nucleotides 1238 to 1255, is AAACTTTGCAACACAACC.

Sequences homologous to ISS1 are widely distributed among lactococci and are often associated with, e.g., lactose metabolism, proteinase activity, or phage resistance (8, 23, 24). Many elements of the ISS1 group appear to be involved in the mobilization of nontransferable plasmids by spontaneous cointegration with conjugative plasmids (24, 45, 50, 53) or with a chromosomal conjugative factor (24). ISS1 has also been found in clinical strains of E. faecalis and E. faecium. Interestingly, a copy of the ORF1 transposase 100% identical to the one described in this work is also present in the recently sequenced E. faecalis chromosome (TIGR database; http://www.tigr.org). The presence of this sequence in plasmid pEJ97 corroborates the hypothesis of genetic exchange between the chromosome and plasmids. Therefore, it would be interesting to determine the extent of genetic exchange between enterococci and other lactic bacteria, including lactococci.

ORF6 (named res-ej97) encoded a putative protein comprising 213 amino acids with a molecular mass of 24.7 kDa, with similarity to a superfamily of recombinases which includes plasmid resolvases. The product of this ORF showed a strong homology (97.2% identity) to the resolvase (orf20) of plasmid pAM373 (15) and up to 40 to 50% similarity to a family of DNA recombinases and/or resolvases of transposons from both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria as well as enzymes involved in site-specific DNA inversions (39). The regions of highest similarity correspond to motifs of the recombinase superfamily, and, like the other members of this family, the product of res-ej97 is predicted to possess a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. Such enzymes are thought to contribute to the segregational stability of plasmids by reducing the number of plasmid multimers resulting from homologous recombination (55). However, on the basis of its similarity to other recombinases, we think that the product of res-ej97 is more likely to be a resolvase involved in the resolution of the cointegrated replicon.

(ii) Plasmid replication region.

The segment of DNA between ORF6 (resolvase) and ORF11 was presumed to encode the replication functions of the plasmid since it is a region conserved in members of the pheromone response plasmids in E. faecalis. This DNA region (ORF7 to ORF10) was established on the basis of DNA and protein database homologies (Fig. 2; Table 2). The ORF7 (named orf7) encodes a polypeptide of 67 amino acid residues, with a predicted size of 7.9 kDa. Interestingly, it has a high homology (95% identity) to orf21 from enterococcal plasmid pAM373 (15). Its product is also similar to proteins involved in UV resistance and UV damage DNA repair (the gene is 45.2% identical to uvrC, a repressor of the uvrA gene from the cytolysin plasmid pAD1 in E. faecalis) (38).

ORF8 (named repB) predicts a gene product with high similarities to members of the ParA proteins; ParA is a family of ATPases involved in active partitioning of diverse bacterial plasmids and includes the bacterial proteins IncC, MinD, SopA, and RepA (6). These proteins are thought to play a role in plasmid maintenance and replication. ParA proteins ensure the proper distribution of newly replicated plasmids to daughter cells during cell division (6). The start codon is an unusual TTG and is preceded by a good potential RBS (GGAG) 9 bp upstream.

ORF9 (named orf9) is located 2 nucleotides downstream of ORF8 and spans 294 nucleotides. This ORF could encode a 98-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 11.3 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point of 10.1. A putative SD sequence (GGAGGA) is located upstream of ORF9. This ORF shows up to 33% identity to possible partition proteins in Borrelia burgdorferi (54), and it could be involved (together with the product of ORF8) in pEJ97 partitioning during cell division.

ORF10 (named repA) encodes a polypeptide of 317 amino acids, with a predicted size of 38.1 kDa, which has a statistically significant sequence similarity to the replication initiation proteins (RepA) from several plasmids of gram-positive bacteria: the enterococcal plasmids pAM373 (15), pPD1 (35, 36), pCF10 (48), and pAD1 (59) (68.8, 47.2, 46.9, and 45.3% similarity, respectively) and the staphylococcal plasmid pSK41 (36.9% similarity) (5). This finding establishes an evolutionary link between the replication functions of enterococcal sex pheromone plasmids pEJ97, pAM373, pPD1, and pAD1. Sequence similarity also extends to the nucleotide level between these plasmids (data not shown).

In addition to the these rep genes, the DNA sequence reveals the presence of several structural elements that may represent sites of DNA-protein interaction, represented by small stretches of relatively high A+T content upstream of repA and the presence of two groups of 10- and 20-bp end-to-end direct repeats (iterons): nucleotides 6536 to 6554 (AAATATACAA) and 6548 to 6585 (TATACAATGTATATTTTGTA), respectively.

Within this region, we also found another ORF (named ORFD) with an orientation opposite to ORF7 to ORF10 (Table 2; Fig. 2). This ORF could encode a 71-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 8.4 kDa, without any significan homology to other proteins. A putative SD sequence (GAAAG) was located upstream of ORFD.

(iv) Pheromone response region.

A search of the GenBank database revealed that several ORFs from the pEJ97 fragment cloned in pGEM-57 have significant homology to genes of the pheromone response regulatory region of pPD1 (35), pAD1 (56), pCF10 (48), and the recently characterized plasmid pAM373 from E. faecalis (15). These correspond to ORF11, ORF12, and ORFE (Fig. 2; Table 2).

ORF11 (designated traC) encodes a product of 545 residues, with a molecular mass of 60.8 kDa. The start codon is an unusual GTG and is preceded by a good potential RBS (GGAGG) 9 bp upstream. Comparison of the amino acid sequence of TraC with those of the TraC homologues from plasmids pPD1, pCF10 (prgZ in this plasmid), pAD1, and pAM373 showed very significant identities (87.9, 79.6, 67.9, and 43.4%, respectively). A conventional (ATG) start site 17 amino acids downstream is unlikely because it lacks a strong RBS. Moreover, the predicted size of the GTG-initiated protein is closer to that of the TraC protein from these plasmids. Like its homologues, TraC has a sequence somewhat characteristic of a surface lipoprotein, with amino acid positions 19 to 23 (LASCG) corresponding to the “lipobox.” The function of TraC has been previously described (35, 36). It is a surface lipoprotein that binds exogenous pheromone or inhibitor peptide and transfers it to a host-encoded oligopeptide uptake system. TraC is also similar to oligopeptide-binding proteins in E. coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Bacillus subtilis, and Lactococcus lactis (7, 56).

ORF12 (designated traB) encodes a predicted product of 384 residues with a molecular mass of 43.5 kDa. The deduced TraB protein has hydrophobic residues in its C-terminal structure. Comparisons of the amino acid sequence of TraB with those TraB from plasmid pPD1 and PrgY from pCF10 and pAD1 showed significant similarity (with 99.2, 77.1, and 46.4%, respectively, of the aligned amino acid residues being identical). The TraB protein is thought to be involved in shutdown of endogenous pheromone production in cells carrying the respective plasmid (35, 36).

Downstream of ORF12, an incomplete open reading frame (ORFE) is transcribed leftward relative to the map in Fig. 2. The predicted partial amino acid sequence (181 amino acids) showed a strong similarity to the C-terminal end of TraA from plasmid pPD1 (91.4% of the aligned amino acid residues are identical), TraA from plasmid pAD1 (26.9% identity) and TraA from plasmid pAM373 (23.4% identity). The TraA protein is thought to be a negative regulator, which binds DNA and negatively regulates expression of traE1 in plasmid pAD1 (21, 35, 36). traE1 codes for a protein (TraE1) which positively regulates all or most structural genes related to conjugation (21, 35, 36). These data support the idea that the plasmid pEJ97 could have a sex pheromone regulation system similar to that of previously described plasmids (such as pPD1).

Concluding remarks.

The nucleotide sequence obtained for a 11.3-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment of plasmid pEJ97 from E. faecalis EJ97 provides insights into the genetic organization of enterococcal pheromone-responding plasmids. In this DNA fragment, four modules have been found: the bacteriocin EJ97 determinants, the putative transposase-resolvase genes, the plasmid replication region, and the cluster of pheromone-response genes. The transposon-like structure encompassing the genetic region involved in bacteriocin production, along with the pheromone response genes detected, suggest that production of enterocin EJ97 may be a highly mobile trait that can be transferred from host to host by plasmid mating and also from the transferred plasmid to other plasmids and to the recipient chromosome. Nevertheless, no other strains producing bacteriocin EJ97 have been reported so far. Further studies are necessary to analyze the peculiarities of the present gene cluster and to identify all genes involved in bacteriocin production in E. faecalis EJ97.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Junta de Andalucía (Plan Andaluz de Investigación, CVI160 group).

We thank Enrique Méndez and Emilio Camafeita for peptide sequencing of EJ97 fragments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abriouel, H., M. Maqueda, A. Gálvez, M. Martínez-Bueno, and E. Valdivia. 2002. Inhibition of bacterial growth, enterotoxin production, and spore outgrowth in strains of Bacillus cereus by bacteriocin AS-48. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1473-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altena, K., A. Guder, C. Cramer, and G. Bierbaum. 2000. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic mersacidin: organization of a type B lantibiotic gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, D. G., and L. L. McKay. 1983. A simple and rapid method for isolating large plasmid DNA from lactic streptococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46:549-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balla, E., L. M. Dicks, M. du Toit, M. J. van der Merwe, and W. Holzapfel. 2000. Characterization and cloning of the genes encoding enterocin 1071A and enterocin 1071B, two antimicrobial peptides produced by Enterococcus faecalis BFE 1071. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1298-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg, T., N. Firth, S. Apisiridej, A. Hettiaratchi, A. Leelaporn, and R. A. Skurray. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence of pSK41: evolution of staphylococcal conjugative multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 180:4350-4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bignell, C., and C. M. Thomas. 2001. The bacterial ParA-ParB partitioning proteins. J. Biotechnol. 91:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgoin, F., G. Guedon, M. Pebay, Y. Roussel, C. Panis, and B. Decaris. 1996. Characterization of a mosaic ISS1 element and evidence for the recent horizontal transfer of two different types of ISS1 between Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactococcus lactis. Gene 178:15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, P., F. Qi, J. Novak, and P. Caufield. 1999. The specific genes for lantiobiotic mutacin II biosynthesis in Streptococcus mutans T8 are clustered and can be transferred en bloc. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1356-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cintas, L. M., P. Casaus, H. Holo, P. E. Hernández, I. F. Nes, and L. S. Håvarstein. 1998. Enterocins L50A and L50B, two novel bacteriocins from Enterococcus faecium L50, are related to staphylococcal hemolysins. J. Bacteriol. 180:1988-1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cintas, L. M., P. Casaus, C. Herranz, L. S. Håvarstein, H. Holo, P. E. Hernández, and I. F. Nes. 2000. Biochemical and genetic evidence that Enterococcus faecium L50 produces enterocins L50A and L50B, the sec-dependent enterocin P, and a novel bacteriocin secreted without an N-terminal extension termed enterocin Q. J. Bacteriol. 182:6806-6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleveland, J., T. J. Montville, I. F. Nes, and M. L. Chikindas. 2001. Bacteriocins: safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 71:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coligan, J. E., B. M. Dunn, H. L. Ploegh, D. W. Speicher, and P. T. Wingfield (ed.). 1997. Current protocols in protein science. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 15.De Boever, E. H., D. B. Clewell, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pAM373: complete nucleotide sequence and genetic analyses of sex pheromone response. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1327-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diep, D. B., and I. F. Nes. 2002. Ribosomally synthesized antibacterial peptides in Gram positive bacteria. Curr. Drug Targets 3:107-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ennahar, S., K. Sonomoto, and A. Ishizaki. 1999. Class IIa bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: antibacterial activity and food preservation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 87:705-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ennahar, S., T. Sashihara, K. Sonomoto, and A. Ishizaki. 2000. Class IIa bacteriocins: biosynthesis, structure and activity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:85-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fath, M. J., and R. Kolter. 1993. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol. Rev. 57:995-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franz, C. M., A. Grube, A. Herrmann, H. Abriouel, J. Starke, A. Lombardi, B. Tauscher, and W. H. Holzapfel. 2002. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the two-peptide bacteriocin enterocin 1071 produced by Enterococcus faecalis FAIR-E 309. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2550-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujimoto, S., and D. B. Clewell. 1998. Regulation of the pAD1 sex pheromone response of Enterococcus faecalis by direct interaction between the cAD1 peptide mating signal and the negatively regulating, DNA-binding TraA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6430-6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gálvez, A., E. Valdivia, H. Abriouel, E. Camafeita, E. Méndez, M. Martínez- Bueno, and M. Maqueda. 1998. Isolation and characterization of enterocin EJ97, a bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecalis EJ97. Arch. Microbiol. 171:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasson, M. J. 1990. In vivo genetic systems in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87:43-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasson, M. J., S. Swindell, S. Maeda, and H. Dodd. 1992. Molecular rearrangement of lactose plasmid DNA associated with high-frequency transfer and cell aggregation in Lactococcus lactis 712. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3213-3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore, M. S., R. A. Segarra, M. C. Booth, C. P. Bogie, L. R. Hall, and D. B. Clewell. 1994. Genetic structure of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1- encoded cytolytic toxin system and its relationship to lantibiotic determinants. J. Bacteriol. 176:7335-7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giraffa, G. 2002. Enterococci from foods. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jack, R. W., J. R. Tagg, and B. Ray. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:171-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaenhammer, T. R. 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:39-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein, C., and K. D. Entian. 1994. Genes involved in self-protection against the lantibiotic subtilin produced by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2793-2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez, B., A. Rodriguez, and J. E. Suárez. 2000. Lactococcin 972, a bacteriocin that inhibits septum formation in lactococci. Microbiology 146:949-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Bueno, M., M. Maqueda, A. Gálvez, B. Samyn, J. van Beeumen, J. Coyette, and E. Valdivia. 1994. Determination of the gene sequence and the molecular structure of the enterococcal peptide antibiotic AS-48. J. Bacteriol. 176:6334-6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-Bueno, M., E. Valdivia, A. Gálvez, J. Coyette, and M. Maqueda. 1998. Analysis of the gene cluster involved in production and immunity of the peptide antibiotic AS-48 in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 27:347-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendoza, F., M. Maqueda, A. Gálvez, M. Martínez-Bueno, and E. Valdivia. 1999. Antilisterial activity of peptide AS-48 and study of changes induced in the cell envelope properties of an AS-48-adapted strain of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:618-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moll, G. N., W. N. Konings, and A. J. M. Driessen. 1999. Bacteriocins: mechanism of membrane insertion and pore formation. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:185-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakayama, J., K. Yoshida, H. Kobayashi, A. Isogai, D. Clewell, and A. Suzuki. 1995. Cloning and characterization of a region of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pPD1 encoding pheromone inhibitor (ipd), pheromone sensitivity (traC), and pheromone shutdown (traB) genes. J. Bacteriol. 177:5567-5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakayama, J., Y. Takanami, T. Horii, S. Sakuda, and A. Suzuki. 1998. Molecular mechanism of peptide-specific pheromone signaling in Enterococcus faecalis: functions of pheromone receptor TraA and pheromone-binding protein TraC encoded by plasmid pPD1. J. Bacteriol. 180:449-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nes, I. F., D. Bao Diep, L. S. Håvarstein, M. B. Brurberg, V. Eijsink, and H. Holo. 1996. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 70:113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozawa, Y., K. Tanimoto, S. Fujimoto, H. Tomita, and Y. Ike. 1997. Cloning and genetic analysis of the UV resistance determinant (uvr) encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pAD1. J. Bacteriol. 179:7468-7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulsen, I. T., M. T. Gillespi, T. G. Littlejohn, O. Hanvivatvong, S. J. Rowland, K. G. H. Dyke, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Characterisation of sin, a potential recombinase-encoding gene from Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 141:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polzin, K. M., and M. Shimizu-Kadota. 1987. Identification of a new insertion element, similar to gram-negative IS26, on the lactose plasmid of Streptococcus lactis ML3. J. Bacteriol. 169:5481-5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quirantes, R., A. Gálvez, E. Valdivia, I. Martin, M. Martínez-Bueno, E. Méndez, and M. Maqueda. 1995. Purification of sex pheromones specific for pMB1 and pMB2 plasmids of Enterococcus faecalis S-48. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:629-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raze, D., O. Dardenne, S. Hallut, M. Martínez-Bueno, J. Coyette, and J. M. Ghuysen. 1998. The gene encoding the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 3r in Enterococcus hirae S185R is borne on a plasmid carrying other antibiotic resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:534-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichelt, T., J. Kennes, and J. Krämer. 1984. Co-transfer of two plasmids determining bacteriocin production and sucrose utilization in Streptococcus faecium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 23:147-150. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rincé, A., A. Dufuor, P. Uguen, J. P. Le Pennec, and D. Haras. 1997. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4252-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romero, D. A., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1990. Characterization of insertion sequence IS946, an iso-ISS1 element, isolated from the conjugative lactococcal plasmid pTR2030. J. Bacteriol. 172:4151-4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross, P., M. Galvin, O. McAuliffe, S. M. Morgan, M. P. Ryan, D. P. Twomery, W. J. Meaney, and C. Hill. 1999. Developing applications for lactococcal bacteriocins. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:337-346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rouch, D. A., and R. A. Skurray. 1989. IS257 from Staphylococcus aureus: members of and insertion sequence superfamily prevalent among gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Gene 76:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruhfel, R. E., D. A. Manias, and G. M. Dunny. 1993. Cloning and characterization of a region of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid, pCF10, encoding a sex pheromone binding function. J. Bacteriol. 175:5253-5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 50.Schäfer, A., A. Jahns, A. Geiss, and M. Teuber. 1991. Distribution of the IS elements ISS1 and IS904 in lactococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 80:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider, E., and S. Hunke. 1998. ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) transport systems: functional and structural aspects of the ATP-hydrolyzing subunits/domains. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siezen, R. J., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Comparison of the lantibiotic gene clusters and encoded proteins. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 69:171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smiegielski, A. J. 1990. Characterization of a plasmid involved with cointegrate formation and lactose metabolism in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis OZS1. Arch. Microbiol. 154:560-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevenson, B., K. Tilly, and P. A. Rosa. 1996. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J. Bacteriol. 178:3508-3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swinfield, T. J., L. Janniere, S. D. Ehrlich, and N. P. Minton. 1991. Characterization of a region of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAMβ1 which enhaces the segregational stability of pAMβ1-derived cloning vectors in Bacillus subtilis. Plasmid 26:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanimoto, K., F. Y. An, and D. B. Clewell. 1993. Characterization of the traC determinant of the Enterococcus faecalis hemolysin/bacteriocin plasmid pAD1: binding of sex pheromone. J. Bacteriol. 175:5260-5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomita, H., S. Fujimoto, K. Tanimoto, and Y. Ike. 1996. Cloning and genetic organization of the bacteriocin 31 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pYI17. J. Bacteriol. 178:3585-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Belkum, M. J., and M. E. Stiles. 2000. Nonlantibiotic antibacterial peptides from lactic acid bacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 17:323-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weaver, K. E., D. B. Clewell, and F. An. 1993. Identification, characterization, and nucleotide sequence of a region of Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive plasmid pAD1 capable of autonomous replication. J. Bacteriol. 175:1900-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]