Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the extent to which physician choice, length of patient-physician relationship, and perceived physician payment method predict patients' trust in their physician.

DESIGN

Survey of patients of physicians in Atlanta, Georgia.

PATIENTS

Subjects were 292 patients aged 18 years and older.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Scale of patients' trust in their physician was the main outcome measure. Most patients completely trusted their physicians “to put their needs above all other considerations” (69%). Patients who reported having enough choice of physician (p < .05), a longer relationship with the physician (p < .001), and who trusted their managed care organization (p < .001) were more likely to trust their physician. Approximately two thirds of all respondents did not know the method by which their physician was paid. The majority of patients believed paying a physician each time a test is done rather than a fixed monthly amount would not affect their care (72.4%). However, 40.5% of all respondents believed paying a physician more for ordering fewer than the average number of tests would make their care worse. Of these patients, 53.3% would accept higher copayments to obtain necessary medical tests.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients' trust in their physician is related to having a choice of physicians, having a longer relationship with their physician, and trusting their managed care organization. Most patients are unaware of their physician's payment method, but many are concerned about payment methods that might discourage medical use.

Keywords: patients' trust, choice of physician, patient-physician relationship, physician payment method

Trust is a fundamental aspect of the patient-physician relationship.1–5 Even well-informed and knowledgeable patients have to rely on their physicians to provide them with appropriate information, keep personal information confidential, provide competent care, and act in their best interests. In spite of the importance of trust to the patient-physician relationship, there are few studies of the factors related to patients' trust in their physicians.

One predictor of trust in social relationships is the length of those relationships 6–8 and there is reason to believe this would hold for patient-physician relationships.9 Having a choice of physician is important to many patients, 10–13 and it is possible that wider choices would encourage greater trust in the physician eventually chosen. Recent developments in health care delivery also make it plausible that the way physicians are paid could influence patients' trust in them. Reports regularly appear in the popular press about how new managed care arrangements may compromise the care provided to patients. Health service researchers have shown that payment methods may have an impact on clinical decision making.14–16 We know of no empirical studies that have examined whether patients' beliefs about how their physician is paid affect their trust in the physician. In the study described herein, we interviewed a probability sample of patients covered by a large health care insurer in Atlanta. We assessed how patients thought their physicians were paid and whether their perceptions were accurate. We also examined whether availability of a choice of physicians, length of patient-physician relationship, or perceived physician payment method was related to the patients' trust in their physician.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

The study was conducted in Atlanta in a national managed care organization. Eligible patients were enrollees aged 18 years and older who made at least one visit to a primary care office (family practice, internal medicine, obstetrics/gynecology) during the period between January 1994 and June 1995. Patients were selected using a two-stage, cluster sample. First, we identified all primary care physicians who had at least 40 eligible plan members in their practices. We randomly selected 15 salaried and 15 fee-for-service physicians from this group. There were no physicians paid on a capitated basis in this study. Next, we randomly selected 40 patients between the ages of 18 and 65 from each physician's practice. To ensure an adequate sample of elderly respondents, 300 patients who were aged 65 years and older were randomly sampled independent of physician practice.

Of the 1,480 patients we attempted to reach for a telephone interview, 453 were contacted and screened for eligibility. Of those screened, 43 (9%) were ineligible: 18 said they did not have a “regular doctor”; 1 did not report having a primary care office visit over the past 2 years; 12 did not speak English; and 12 were deemed ineligible because they had no overall opinion of their experiences with the sampled doctor. Of the 410 eligible patients who were contacted, 292 (71.2%) completed the telephone interview.

Measures

In 1996, we developed a 16-item scale to assess patients' trust in their physician (unpublished manuscript). To develop our new scale, we modified an existing scale by modifying the wording of some items to refer specifically to the patient's physician.17 Several new items related to confidentiality and reliability were included and tested. In addition, one other competency item was added and seven items were added that assessed patients' trust in their physicians to provide necessary care under various cost constraints and administrative restrictions. We used factor analyses and other standard psychometric techniques, such as examining item-criterion correlations and the internal consistency of different subsets of items to select items that formed a unidimensional measure of trust in physician. The resulting scale had an internal consistency (coefficient α) of 0.90.

The patient questionnaire also included questions about whether patients had “enough choice” of physicians, whether patients had more than one health plan option, and length of relationship with their physician. To assess awareness of payment methods, respondents were asked to identify their physician's payment method as fee-for-service (doctor's pay is based on “the number of tests and procedures that are carried out”), capitation (doctor's pay is based on “some fixed monthly amount,” which is dependent on the “number of patients in doctor's practice”), or salary (doctor's pay is based on “a straight salary”). Respondents also were asked how they thought their care would be affected if their physician was “paid each time he/she carries out a test rather than a fixed monthly amount” and “paid more for ordering fewer than the average number of tests.” The respondents who believed that the physician getting paid more for ordering fewer tests would adversely affect their care were asked if they would be willing to “pay a higher copayment to get the tests that (they thought they) needed.” To evaluate patients' general trust in people, the Survey of Cynicism 18 and Benevolence of People 19 scales were used. Information on patients' race, education, income, and health status was also collected in the interviews. The measure of health status was a single rating of perceived health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor). Information on patients' age, gender, length of enrollment in health plan, and number of primary care office visits was obtained from administrative files.

Statistical Analyses

To assess the relation between patient trust and hypothesized determinants of trust, we estimated linear regression models. The dependent variable in our models was the patient trust score. The independent variables included having enough choice of physicians, having more than one health plan option, length of the patients' relationship with their physician, patients' trust in their managed care organization, and physician payment method. Patients' perception of their physician's payment method (fee-for-service, salary, or capitation) was specified as a series of dummy variables, and the omitted group comprised patients who said they did not know how their physician was paid. Control variables included gender, race, education, self-reported health status, general trust in people, length of enrollment in the health plan, and number of primary care office visits. Patients with missing data for any of these variables (n= 48) were excluded from the regression analysis. We analyzed patients who did not respond to the income question (n= 54) by using different income specifications (quartile, median, and continuous) and a dummy variable representing missing data in the regression models. The coefficient of the explanatory variables and their significance were statistically unchanged in these regression models.

RESULTS

There were some differences between the patients who completed the telephone interview and those who did not. More of the respondents than nonrespondents were female (77.7% vs 66.1%, p < .05). Respondents also had more primary care office visits (± SD) than nonrespondents (3.9 ± 3.3 vs 3.2 ± 3.0 visits, p < .05). There was no statistically significant difference between the respondents and non-respondents in mean age. Information on race, education, income, and self-reported health status was not available for nonrespondents.

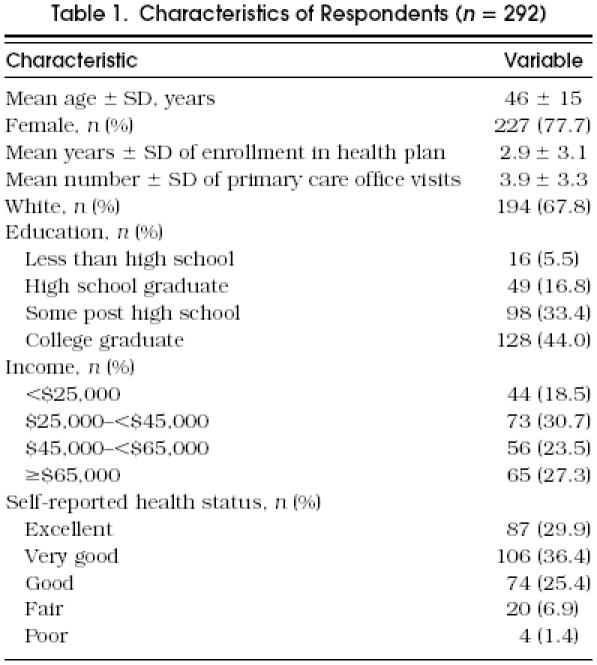

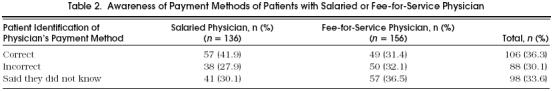

The characteristics of survey respondents are presented in Table 1) Approximately two thirds of the respondents incorrectly identified their physician's payment method or said they did not know how their physician was paid (Table 2 More patients of salaried physicians correctly identified their physician's payment method than patients of fee-for-service physicians, but this difference in awareness of payment methods was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents (n= 292)

Table 2.

Awareness of Payment Methods of Patients with Salaried or Fee-for-Service Physician

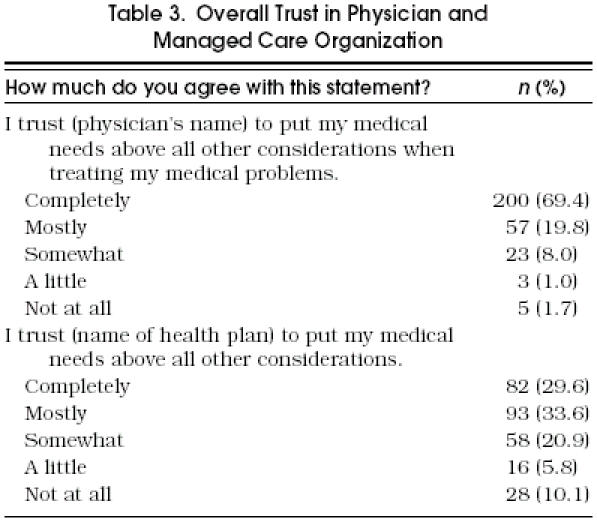

The majority of respondents (60.4%) completely trusted their physician “to put their medical needs above all other considerations when treating their medical problems” (Table 3) Few patients did not trust their physician at all (1.7%). Approximately 30% of the respondents completely trusted their managed care organization “to put their medical needs above all other considerations,” while approximately 10% of the respondents did not trust their health plan at all (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall Trust in Physician and Managed Care Organization

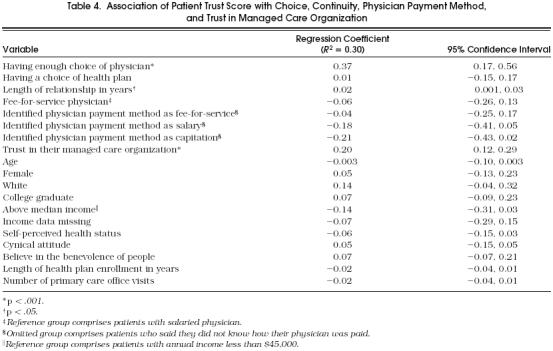

In a multivariate model, several variables were significant independent predictors of patients' trust in their physician (Table 4) Patients who said they had enough choice of physicians were more likely to trust their physician (p < .001). Having a choice of health plan was not associated with a higher physician trust score. A longer patient-physician relationship was associated with a higher patient trust score (p < .05). Patients' trust in their managed care organization was also positively associated with trust in their physician (p < .001). Patients of fee-for-service physicians were not more likely to trust their physicians than patients of salaried physicians. Patients who thought their physicians were paid on a capitated basis were less likely to trust their physicians, but this association was not statistically significant. Healthier patients also tended to trust their physicians more, but this association was not statistically significant. Cynicism and belief in the goodness of people were not significantly associated with patients' trust in their physician.

Table 4.

Association of Patient Trust Score with Choice, Continuity, Physician Payment Method, and Trust in Managed Care Organization

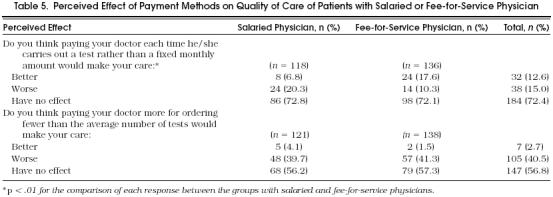

Nearly three fourths of all respondents believed that payment methods that may encourage use of medical services would have no effect on the quality of their care (Table 5) However, more patients of fee-for-service physicians (17.6%) than of salaried physicians (6.8%) believed their care would improve if their physician was paid “each time (a test is carried out) rather than a fixed monthly amount.” More patients of salaried physicians (20.3%) believed these incentives would make their care worse than patients of fee-for-service physicians (10.3%).

Table 5.

Perceived Effect of Payment Methods on Quality of Care of Patients with Salaried or Fee-for-Service Physician

More than half of all respondents believed that paying a physician more for ordering fewer than the average number of tests would have no effect on the quality of their care (Table 5); however, 40.5% believed these payment methods would adversely affect their care. There was no significant difference between the groups with salaried and fee-for-service physicians in perceived effect of payment methods that may discourage use of medical services in their care. Among the patients who believed that incentives that might discourage use of medical services would make their care worse, 53.3% would be willing to make a higher copayment to receive tests they thought they needed. There was no significant difference between the groups with salaried and fee-for-service physicians in their willingness to make a higher copayment to obtain necessary medical tests.

DISCUSSION

Organizational changes in health care have altered the relationship between physicians and third party payers, and have the potential of affecting patient-physician relationships.20 –28 Some contend that managed care's emphasis on preventive and primary care 29 –31 has led to more cost-effective clinical practice. Others have raised concerns that managed care incentives and rules place physicians in a position with potentially conflicting obligations to patients and insurers. 32 –36 In light of significant changes, it is important to understand better factors affecting patients' trust in their physicians, a foundation of the patient-physician relationship.

Most patients in our study trusted their physicians to act in their best interests. Nearly three fourths of all respondents completely trusted their physicians to “put (their) medical needs above all other considerations.” Fewer patients completely trusted their managed care organization, which is consistent with declining social trust in all institutions, 37, 38 and with a natural inclination to trust an individual more than an organization. Nevertheless, organizations can develop and implement policies to reinforce trust.8, 39 Patients who trusted their managed care organization were more likely to trust their physicians.

Patients who reported having enough choice of physicians were more likely to trust their physician. However, having more than one health plan option was not associated with physician trust. It may be that patients are less concerned about how many health plan options are available to them as long as their health plan provides them with enough choice of physicians. Patients who had longer patient-physician relationships were also more likely to trust their physicians. Trust is developed through an iterative process of interaction and experience,8, 40 and continuity of care may provide patients with the time necessary for interpersonal trust to develop.

To varying degrees, managed care plans limit patients' choice of physicians and restrict access to specialists. For example, patients in staff-model HMOs are usually limited to physicians who are directly employed by the health plan. Conversely, point-of-service (POS) plans and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) are less restrictive and offer patients more choice of physicians outside the plan (with increased patient cost sharing). Over the past few years, HMOs have experienced little growth in their membership. In a recent survey of employers, the percentage of working Americans insured by HMO plans was unchanged at 27% from 1995 to 1996.41 Conversely, health plan options that offer patients more open access to a larger panel of physicians including specialists have experienced steady enrollment growth (POS plans from 14% to 19% and PPOs from 29% to 31% from 1995 to 1996). Currently, over 80 million people are enrolled in PPOs,42 and having a choice of physicians is most likely one of the factors contributing to their growing popularity among consumers.

Although the public appears to favor health plans with greater choice of physicians, continuity of patient-physician relationships has become more difficult to sustain in our employment-based health care system. Decisions about continuity of care are made by employers, health plans, physicians, and plan members for a variety of reasons, including issues of quality, cost, and convenience. When employers switch health plans, existing patient-physician relationships cannot be maintained if the new health plan selected by the employer has a different panel of physicians. Even when employers remain with the same health plan, physicians deselected by the plan on the basis of quality performance standards, utilization measures, credentialing, or other criteria are no longer eligible to provide care to enrollees of that plan.43–46 Physicians can also deselect health plans and choose not to be a participating provider, but this is less of an issue in mature managed care markets.47–49 Plan members may change health plans based on provider preference, plan benefits, or cost considerations.

Nearly two thirds of all respondents either did not know or incorrectly identified their physician's payment method. When patients were asked to assess the impact of different payment methods on the quality of care, most believed that payment methods would have no effect on their care. However, a large percentage of all respondents believed that paying physicians “more for ordering fewer than the average number of tests” would make their care worse.

Although patients expressed concern about certain payment strategies, their perceptions of how their own physician was paid were not significantly related to their trust in him or her. This may be because once a patient-physician relationship is established any effects of attitudes about the physician's reimbursement are minor compared with other factors that affect patient trust. The American Association of Health Plans has decided to provide information about physician payment methods to health plan members who request it. It is unclear when patients should be given such information, how this information should be presented, and who should inform them.43, 50

We were unable to contact a large number of patients originally selected from administrative records. The observed differences between the respondent and nonrespondent groups could contribute to response bias. However, it seems unlikely that having a choice of physician and maintaining continuity of care would be less relevant determinants of physician trust in the nonrespondent group.

Systems of care that foster patient trust enhance the quality of the patient-physician relationship. Our findings suggest that patients who have a choice of physicians and are in longer, stable patient-physician relationships are more likely to trust their physician. Further studies examining patient-physician relationships under different payment arrangements including capitated and indemnity methods may provide us with a better understanding of factors contributing to patients' trust in their physicians.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Prudential Center for Health Care Research. During the conduct of this study, Dr. Cleary was a consultant to the Prudential Center for Health Care Research. The authors thank Barbara McNeil, MD, PhD, and Carol McPhillips-Tangum, MPH, for their helpful comments on the study, Sean Lee for data programming, and Linda Emanuel, MD, PhD, for her review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Beauchamp T, Childless J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. New York, NY: Free Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macklin R. Enemies of Patients. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodwin M. Medicine, Money and Morals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuel EJ, Dubler NN. Preserving the physician-patient relationship in the era of managed care. JAMA. 1995;273:323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber B. The Logic and Limits of Trust. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gambetta D, editor. Trust Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. New York, NY: Blackwell; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer RM, Tyler TR, editors. Frontiers of Theory and Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 1996. Trust in Organizations: eds. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mechanic D. Changing medical organization and the erosion of trust. Milbank Q. 1996;74:171–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blendon RJ, Knox RA, Brodie M, Benson JM, Chervinsky G. Americans compare managed care, Medicare, and fee-for-service. J Am Health Policy. 1994;4:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoerger TJ, Howard LZ. Search behavior and choice of physician in the market for prenatal care. Med Care. 1995;33:332–49. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mechanic D, Ettel T, Davis D. Choosing among health insurance options: a study of new employees. Inquiry. 1990;27:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell JH, Dunn JP. Employee's choice of a health plan and their subsequent satisfaction. J Occup Med. 1984;26:361–6. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillman AL, Pauly MV, Kerstein JJ. How do payment methods affect physicians' clinical decisions and the financial performance of health maintenance organizations? N Engl J Med. 1989;321:86–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907133210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillman AL. The impact of physician payment methods on high-risk populations in managed care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8(Suppl 1):S23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulmasy DP. Physicians, cost control, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:920–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-11-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:1091–100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanter DL, Mirvis PH. Living and Working in an Age of Discontent and Disillusion. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 1989. The Cynical Americans: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janoff-Bulman R. Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: applications of the schema construct. Soc Cognition. 1993;7:113–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman PG, Shellow RA. Privacy and autonomy in the physician-patient relationship: independent contracting under Medicare and implications for expansion into managed care. J Leg Med. 1995;16:509–43. doi: 10.1080/01947649509510992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wennberg JE. Health care reform and professionalism. Inquiry. 1994;31:296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sederer LI, Mirin SM. The impact of managed care on clinical practice. Psychiatr Q. 1994;65:177–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02356119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubler NN. Individual advocacy as a governing principle. J Case Manage. 1992;1:82–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenthal TC, Teimenschneider TA, Feather J. Preserving the patient referral process in the managed care environment. Am J Med. 1996;100:338–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korcok M. Capitation begins to transform the face of American medicine. Can Med Assoc J. 1996;154:688–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn MB. Power, professionalism, and patient advocacy. Am J Surg. 1995;170:407–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apple GJ. Who bears the risk when physicians are also insurers? Minn Med. 1995;78:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clouthier M. The evolution of managed care. Trends Health Care Law Ethics. 1995;10:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solberg LI, Isham G, Kottke TE. Competing HMOs collaborate to improve preventive services. Jt J Qual Improv. 1995;21:600–10. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow RW, Gooding AD, Clark C. Improving physicians' preventive health care behavior through peer review and payment methods. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:165–9. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson JA, Robinson KJ, Lewis DJ. Balancing quality of care and cost-effectiveness through case management. Anna J. 1992;19:182–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angell M. The doctor as double agent. Kennedy Inst J Ethics. 1993;3:279–86. doi: 10.1353/ken.0.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orentlicher D. Managed care and the threat to the patient-physician relationship. Trends Health Care Law Ethics. 1995;101:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swee DE. Health care system reform and the changing physician-patient relationship. N J Med. 1995;92:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodwin MA. Conflicts in managed care. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:604–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelms CR. Ethical physicians cannot serve two masters. Minn Med. 1994;77:51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipset SM, Schneider W. Business, Labor, and Government in the Public Mind. New York, NY: Free Press; 1983. The Confidence Gap: [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheppard BH, Lewicki RJ, Minton JW. The Search for Fairness in the Workplace. Lexington, Mass: Lexington Books; 1992. Organizational Justice: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray BH. Trust and trustworthy care in the managed care era. Health Affairs. 1997;16:34–49. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duck S, Perlman D, editors. Understanding Personal Relationships. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans. New York, NY: Foster Higgins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Group Health Association of America/American Medical Care and Review Association Managed Health Care Directory. Washington, DC: AMCRA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mechanic D, Schlesinger M. The impact of managed care on patients' trust in medical care and their physicians. JAMA. 1996;275:1693–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montague J. Managed care is dumping many physicians, but some aren't going to take it lying down. Striking back. Hosp Health Netw. 1994;68:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey CW. How to avoid being dropped from managed care plans. Postgrad Med. 1994;95:59–62. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1994.11945853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guglielmo WJ. How to avoid deselection. Med Econ. 1996;73:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graddy B. TMA takes aim against deselection. Tex Med. 1994;90:14–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ortolon K. Deselection, round two: TMA takes due process with managed care organizations to US Congress. Tex Med. 1994;90:20–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brouillette JN. Bilateral deselection. J Fla Med Assoc. 1995;82:423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morreim EH. Economic disclosure and economic advocacy. New duties in the medical standard of care. J Leg Med. 1991;12:275–329. doi: 10.1080/01947649109510858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]