Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine if women who experience low-severity violence differ in numbers of physical symptoms, psychological distress, or substance abuse from women who have never been abused and from women who experience high-severity violence.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional, self-administered, anonymous survey.

SETTING

Four community-based, primary care, internal medicine practices.

PATIENTS

Survey respondents were 1,931 women aged 18 years or older.

SURVEY DESIGN

Survey included questions on violence; a checklist of 22 physical symptoms; the Symptom Checklist-22 (SCL-22) to measure depression, anxiety, somatization, and self-esteem; CAGE questions for alcohol use; and questions about past medical history.Low-severity violence patientshad been “pushed or grabbed” or had someone “threaten to hurt them or someone they love” in the year prior to presentation.High-severity violence patientshad been hit, slapped, kicked, burned, choked, or threatened or hurt with a weapon.

RESULTS

Of the 1,931 women, 47 met criteria for current low-severity violence without prior abuse, and 79 met criteria for current high-severity violence without prior abuse, and 1,257 had never experienced violence. The remaining patients reported either childhood violence or past adult abuse. When adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics, the number of physical symptoms increased with increasing severity of violence (4.3 for no violence, 5.3 for low-severity violence, 6.4 for high-severity violence, p < .0001). Psychological distress also increased with increasing severity of violence (mean total SCL-22 scores 32.6 for no violence, 35.7 for low-severity violence, 39.5 for high-severity violence, p < .0001). Women with any current violence were more likely to have a history of substance abuse (prevalence ratio [PR] 1.8 for low-severity, 1.9 for high-severity violence) and to have a substance-abusing partner (PR 2.4 for both violence groups).

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, even low-severity violence was associated with physical and psychological health problems in women. The data suggest a dose-response relation between the severity of violence and the degree of physical and psychological distress.

Keywords: violence, severity; women's health

In populations of female primary care patients, the prevalence of current violence ranges from 6% to 23%.1–8 Some of the variation in the prevalence occurs because some researchers include certain types of low-severity physical actions such as pushing, shoving, or grabbing in their definition of abuse, while others do not.1–8 Because studies have not separated low- from high-severity violence in their analyses, it is unclear whether the reported associations between violence and physical symptoms, psychological problems, and substance abuse are due to high-severity violence, low-severity violence, or both.1, 2, 9–15

METHODS

Survey Administration and Content

Study methodology has been previously described in detail.1, 2 Briefly, all female patients aged 18 years or older who presented from February to July 1993 to four community-based primary care, internal medicine practices were considered candidates to complete an anonymous, self-administered survey. A woman was ineligible if she was unable to read because of blindness, having forgotten her glasses, illiteracy, or being a non-English speaker; mentally retarded or demented; too acutely ill; or accompanied by a companion who refused to leave her alone in the examining room.

The survey instrument included questions on sociodemographic characteristics; the presence or absence of 22 physical symptoms occurring in the prior 6 months; the Symptom Checklist-22 (SCL-22) to measure psychological distress 16–17; CAGE questions for alcohol abuse 18; questions on illicit drug use; childhood, past adult, and current violence 15; and past medical history. The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Patients were asked if they had experienced any of 22 physical symptoms in the prior 6 months: frequent or severe headaches; loss of appetite; frequent or serious bruises; nightmares; vaginal discharge; eating binges or making self vomit; diarrhea; broken bones, sprains, or serious cuts; pain in the pelvis or genital area; fainting or passing out; abdominal or stomach pain; breast pain; problem passing urine; chest pain; problem with sleeping; shortness of breath; constipation; back pain; frequent tiredness; face pain; choking sensation; and falls. The SCL-22 has 22 questions to measure both total psychological distress and four subscales: depression, anxiety, somatization, and interpersonal sensitivity (self-esteem). Possible total scores range from 22 (no psychological distress) to 88 (the highest distress); subscale scores can range from 4 to 28. A total score of 47.3 or more reportedly corresponds to a diagnosable DSM-IV disorder.16, 17

Current and past illicit drug use was measured by asking if the patient was currently using street drugs and “had ever used,” respectively. We also asked about lifetime miscarriage and psychiatric admissions, and emergency department use in the 6 months prior to presentation.

Definitions

For this study, the following definitions were used to classify the respondents' exposure to violence. Current high-severity violence was defined as a “yes” response to either “Within the last year, have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone?” or “Within the last year, has anyone forced you to have sexual activities?”Current low-severity violence was defined as an answer of “yes” to whether anyone had either “pushed or grabbed you” or “threatened to hurt you or someone you love” in the year prior to presentation, but “no” to the more severe types of violence included in the high-severity violence category. Women were included in these categories regardless of the identity of the perpetrator. Because women with past childhood or past adult violence have increased physical symptoms and psychological distress,1 women who reported physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 years or past adult (without current) abuse were excluded from this analysis. No violence was used for patients who denied ever being abused. Because of the wording of the questionnaire, we could not distinguish between patients who had experienced current violence without past adult violence from patients who had experienced both current violence and past adult violence.

Data Analysis

To determine whether there were any differences in sociodemographic characteristics, physical symptoms, psychological distress, or substance abuse among patients with different severities of violence, analyses were performed using χ2for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.19 All statistical tests were performed at the two-sided, 5% level of significance. We also performed a multivariate analysis to study the relation between violence and total SCL-22 score and total physical symptom count controlling for socioeconomic characteristics (age, race, marital status, education, and medical insurance). We used logistic regression to study the relation between violence and substance abuse, substance-abusing partner, suicide attempts, current suicidal ideation, emergency department visits, psychiatric hospitalizations, and lifetime miscarriages controlling for the above socioeconomic characteristics. We used prevalence ratios (PRs) in preference to odds ratios because odds ratios can produce slightly inflated estimates of the effects of factors. A PR in this study is defined as the prevalence of a risk factor in the high- or low-level violence group divided by the prevalence in the no violence group (e.g., prevalence of substance abuse in low-level versus no violence groups).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Respondents

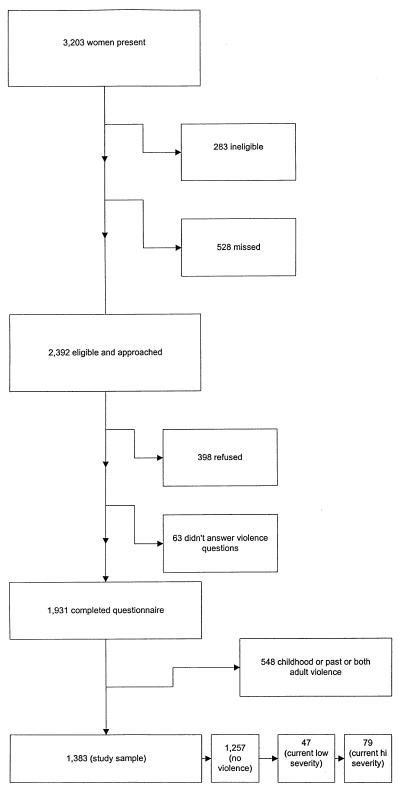

A total of 1,931 women (81% of those approached and eligible) completed the survey (Fig. 1). Of these, 79 (4.1%) met criteria for current high-severity violence exclusively, 47 (2.4%) current low-severity violence exclusively, and 1,257 (65.1%) no violence. The remaining 548 patients (28.4%) reported prior childhood or adult violence.

Figure 1.

Enrollment of study participants.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

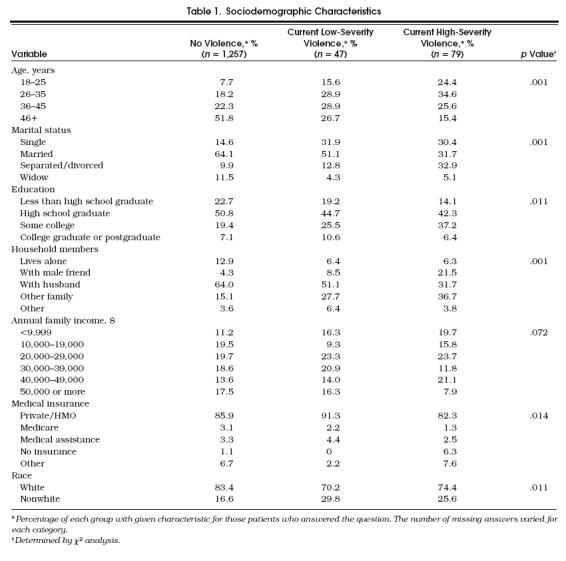

Sociodemographic characteristics of the groups, listed in Table 1, reveal significant univariate associations between socioeconomic characteristics (age, marital status, education, household members, medical insurance status) and violence.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Physical Symptoms

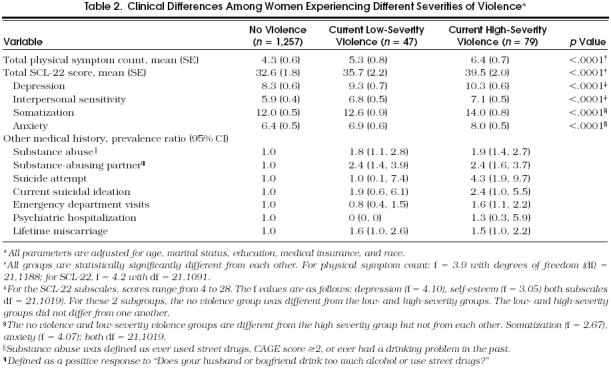

As shown in Table 2, when adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics, the number of physical symptoms increased as the severity of violence increased (p < .0001).

Table 2.

Clinical Differences Among Women Experiencing Different Severities of Violence*

Of 22 specific physical symptoms listed, 4 were more common in the low-level violence group than the no violence group: diarrhea (42.2% vs 23.7%, χ2= 8.08, p < .01), loss of appetite (17.4% vs 7.7%, χ2= 5.68, p= .02), vaginal discharge (32.6% vs 18.7%, χ2= 5.51, p= .02), and abdominal pain (41.3 vs 28.3, χ2= 3.63, p= .06).

Psychological Problems

As shown in Table 2, when adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics, the total SCL-22 score for psychological distress increased as the severity of violence increased. All groups were different from one another (p < .0001), and the relation was linear. For the subscales of depression and self-esteem, the low- and high-severity violence groups were different from the no violence group (p < .0001).

Women in the high-severity violence group were more likely to have had a lifetime suicide attempt (PR 4.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.9, 9.7). There was no difference among groups in lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations.

Substance Abuse

As shown in Table 2, the patients with low-severity violence and those with high-severity violence had a higher level of current or past drug or alcohol abuse and were more likely to have a substance-abusing partner. Patients with high-severity violence were not significantly different from the patients with low-severity violence in the percentage of women having a current or past drug or alcohol problem or having a substance-abusing partner.

Other Medical History

Patients in the group with high-severity violence were slightly more likely to have had an emergency department visit in the 6 months prior to presentation than the other two groups (PR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1, 2.2). Women in either violence group were slightly more likely to have had a lifetime miscarriage (low-severity violence PR 1.6; 95% CI 1.0, 2.6; high-severity violence PR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0, 2.2;p= .05).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that women reporting current, low-severity violence generally had more physical symptoms and more psychological distress than women who reported no violence, but less than women who reported current, high-severity violence. Women experiencing low-severity violence were also more likely to have a history of substance abuse and a substance-abusing partner than women who had never experienced violence.

Our study has several strengths. The population was large and diverse. We used validated questions for psychological distress and alcohol abuse and performed a systematic review of physical symptoms. We performed our study in a primary care setting, which may make it more generalizable than prior research in other health settings.

Our study has some limitations. The number of respondents in the group with low-severity violence was small, limiting the power to detect differences between groups for some characteristics. Because of the stepwise wording in the questionnaire, some of the women in the study may have skipped the question about whether they had been pushed, grabbed, or threatened. We have no information on nonrespondents, and unrecognized bias may have occurred. Finally, this study is cross-sectional and cannot prove causality between low-level violence and physical and psychological symptoms.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates a relation between low-level violence and physical and psychological symptoms. The relation between increasing degrees of violence and increasing physical and psychological problems suggests a dose response—one of several criteria necessary to demonstrate a causal relation.20

Our conclusions suggest that clinicians, researchers, and public health workers should be aware that low-severity violence may be associated with health problems in women. Further investigation should determine whether identification of low-severity violence can improve the clinical management and health outcomes of these women.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by two grants from the Chesapeake Educational Research Trust (03600 and 100-95) of Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians, and by the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.

The authors thank Christopher Dawson, Chris Sciamanna, James Tonascia, Donna Lea, and Val Eleonu for their help in preparation of this manuscript; it was greatly appreciated.

References

- 1.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood violence: unhealed wounds. JAMA. 1997;227:1362–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCauley JM, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The battering syndrome: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(10):737–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullock L, McFarlane J, Bateman LH, Miller V. The prevalence and characteristics of battered women in a primary care setting. Nurse Pract. 1989;14:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamberger LK, Saunders DG, Hovey M. Prevalence of domestic violence in community practice and rate of physician inquiry. Fam Med. 1992;24:283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rath GD, Jarratt LG, Leonardson G. Rates of domestic violence against women by male partners. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1989;2:227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliot BA, Johnson MM. Domestic violence in a primary care setting. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:113–9. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gin NE, Ruker L, Frayne J, Cygan R, Hubbel FA. Prevalence of domestic violence among patients in three ambulatory care internal medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:317–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02597429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plichta S. The effects of women violence on health care utilization and health status: a literature review. Women's Health Issues. 1992;2:154–63. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(05)80264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, et al. Sexual and physical violence in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorder. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Hanson J, et al. Medical and psychiatric symptoms in women with childhood sexual violence. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:658–64. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffe P, Wolfe DA, Wilson S, Zak L. Emotional and physical health problems of battered women. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;625–9 doi: 10.1177/070674378603100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullen PE, Romans-Clarkson SE, Walton VA, Herbison GP. Impact of sexual and physical violence on women's mental health. Lancet. 1988;12:51–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schei B, Bakketeig Gynaecological impact and sexual and physical violence by spouse: a study of intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scale. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koss MP, Koss PG, Woodruff WJ. Deleterious effects of criminal victimization on women's health and medical utilization. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:342–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane J, Parker R, Soeken K, Bullock I. Assessing for violence during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;152:1186–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derogatis LR. Administration Scoring and Procedures Manual for the SCL-90 R. Minneapolis, Minn: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Centor RM, Schnoll SH, Lawton MJ. Screening for alcohol violence using CAGE scores and likelihood ratios. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:774–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Checkoway H, Pearce N, Crawford-Brown DJ. Research Methods in Occupational Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilienfeld DE, Stolley PD. Foundations in Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]