Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate a bedside clinical prediction rule for detecting moderate or severe aortic stenosis.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study with independent comparison to a diagnostic reference standard, doppler echocardiography.

SETTING

Urban university hospital.

PARTICIPANTS

Consecutive hospital inpatients (n = 124) who had been referred for echocardiography.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Participants were examined by a third-year general internal medicine resident and a staff general internist. We hypothesized in advance that absence of a murmur over the right clavicle would rule out aortic stenosis, while the presence of three or four associated findings (slow carotid artery upstroke, reduced carotid artery volume, maximal murmur intensity at the second right intercostal space, and reduced intensity of the second heart sound) would rule in aortic stenosis. Study physicians were unaware of echocardiographic findings. The outcome was echocardiographic moderate or severe aortic stenosis, defined as a valve area of 1.2 cm2or less, or a peak instantaneous gradient of 25 mm Hg or greater. Absence of a murmur over the right clavicle ruled out aortic stenosis (likelihood ratio [LR] 0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.01, 0.44). The presence of three or four associated findings ruled in aortic stenosis (LR 40; 95% CI 6.6, 240). If a murmur was present over the right clavicle, but no more than two associated findings were present, then the examination was indeterminate (LR 1.8; 95% CI 0.93, 2.9).

CONCLUSION

A clinical prediction rule, using simple bedside maneuvers, accurately ruled in and ruled out aortic stenosis.

Keywords: physical examination, heart murmurs, reliability of results

Accurate detection of aortic stenosis is an important clinical goal for the general internist because aortic stenosis is a potentially curable disease, and a major risk factor for perioperative cardiac complications.1 Aortic stenosis may be asymptomatic, or may cause nonspecific symptoms such as angina or dyspnea. Therefore the physical examination is an essential step in the identification of aortic stenosis.

Physical examination by cardiologists can accurately detect aortic stenosis and other significant valvular lesions.2, 3 One study evaluated the accuracy of cardiologists using a bedside clinical prediction rule for detecting aortic stenosis in 86 patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for suspected aortic stenosis.4 The prevalence of aortic stenosis in this study was remarkably high (73%), so the applicability of these results to a less selected population is unclear. Furthermore, the ability of noncardiologists to accurately detect valvular heart disease is uncertain.5, 6

Our objective was to evaluate the accuracy of a clinical prediction rule, using simple bedside physical findings, for detecting moderate to severe aortic stenosis. We also evaluated the interobserver reliability of the various components of the prediction rule. We used general internal medicine staff and residents as examiners, and we enrolled a broad spectrum of patients referred for echocardiography.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted the study during September 1994 (reliability study) and from September to October 1995 (accuracy study) at the Toronto Hospital.

Population

We recruited consecutive hospital inpatients who had been referred for echocardiography by their treating physicians. The majority of referrals were from the general medical wards, which provide secondary-level generalist care, and the cardiology wards, which provide tertiary- and quaternary-level cardiology care. We excluded patients with any of the following characteristics: age less than 50 years, admitted to the coronary care or intensive care unit, unstable angina within 48 hours, myocardial infarction within 6 weeks, recovering from cardiothoracic surgery, previous valve replacement, severe dyspnea at rest, or unable to provide informed consent.

During the study periods, 803 inpatients had echocardiography and 162 were enrolled (124 patients enrolled for the accuracy study and 38 for the reliability study). Reasons for exclusion (number of patients) were as follows: already discharged from hospital (140), age less than 50 years (138), admitted to the coronary care or intensive care unit (123), recovering from cardiothoracic surgery (77), unable to provide informed consent (50), myocardial infarction within 6 weeks (45), and other exclusion criteria (68).

Main Measures

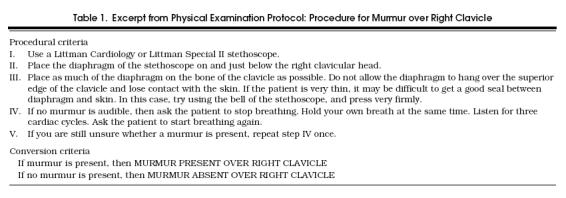

Using methodologic guidelines,7 we develop standardized physical examination methods based on published literature,4, 8, 9 textbooks,10 and discussions with cardiologists (Table 1) The examination included assessment of carotid artery volume and upstroke, second heart sound intensity, murmur intensity, location, and radiation. Study physicians reviewed and discussed the protocol for approximately 30 minutes, and tested the examination on 10 patients.

Table 1.

Excerpt from Physical Examination Protocol: Procedure for Murmur over Right Clavicle

For the accuracy study, there were two study physicians: a third-year resident and a staff general internist. Each physician also obtained a focused clinical history from the patient prior to the physical examination.

For the reliability study, there were six study physicians, including a resident from each of the five postgraduate years (PGY1–PGY5) and a staff internist (the PGY5 resident had just started cardiology training at the time of the study). Each study participant was examined by at least two of the six study physicians. For the reliability study, study physicians did not obtain a clinical history.

All study physicians were unaware of the participants' diagnoses, echocardiographic data, and results of the examinations by other study physicians.

Outcomes

Echocardiograms were analyzed by echocardiographers unaware of the results of the study physician examinations. Moderate to severe aortic stenosis was defined as either a calculated aortic valve area of 1.2 cm2or less, or a peak instantaneous transvalvular gradient of 25 mm Hg or greater.4 An independent echocardiographer reviewed a subset (20%) of echocardiograms, with perfect agreement regarding the presence of moderate or severe aortic stenosis.

Analysis

For the reliability data, we calculated generalized κ coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the method of Fleiss,11 and we interpreted the results using the guidelines of Landis and Koch.12 For the accuracy study, we calculated sensitivities, specificities, and likelihood ratios (LRs). We calculated LRs using ROC Analyzer Software, and 95% CIs using the maximum likelihood option.13

We used previous studies 4, 9 and results of the reliability study to develop a clinical prediction rule for ruling in and ruling out aortic stenosis. We prospectively tested this prediction rule in the accuracy study. The examining physicians were not aware of the content of the clinical prediction rule. For the clinical prediction rule, we compared the accuracy of the resident and the staff internist findings with a logistic regression model for paired categorical data.14

The first step in the clinical prediction rule is to determine whether a murmur is audible over the right clavicle.8 We did not include a step for assessing the presence of any murmur (grade I or louder) because we found the reliability of this assessment was poor. If a murmur is not audible over the right clavicle, then aortic stenosis is ruled out. If a murmur is heard over the right clavicle, the next step is to seek four associated findings: reduced carotid artery volume; slow carotid artery upstroke; reduced second heart sound intensity; and murmur intensity in the second right intercostal space, parasternal area as loud as or louder than murmur intensity in the fifth left intercostal space, midclavicular line. In advance, we established that presence of zero, one, or two associated findings was indeterminate for diagnosing aortic stenosis, while the presence of three or four associated findings rule in aortic stenosis.

Sample Size

Our goal was to ensure sufficiently narrow CIs for ruling out aortic stenosis. We estimated a prevalence of aortic stenosis of 10%, based on results of the reliability study. We assumed that a negative LR of 0.25 would be clinically useful, and that the upper 95% confidence limit should exclude 0.7, yielding a required sample size of 104.15

Ethics

All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the executive of the Toronto Hospital Human Subjects Review Committee.

RESULTS

Accuracy Study

One participant was excluded after the study was completed because the echocardiographer was unable to adequately visualize the aortic valve. The decision to exclude the participant was made independent of the results of the study examinations.

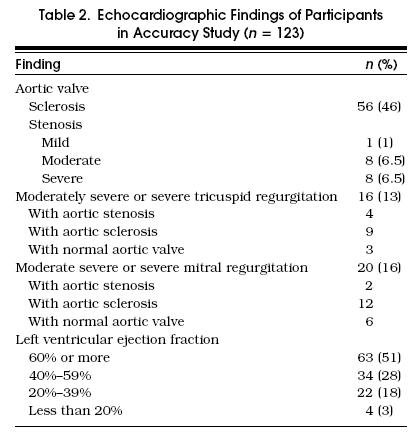

Of the remaining 123 participants, 58% were male, median age was 68 years (interquartile range, 60 –75 years), 53% had a history of angina, 63% had a history of congestive heart failure, and 56% had a history of myocardial infarction. Functional class (Canadian Cardiovascular Society) distribution was class I, 56%; II, 21%; III, 16%; and IV, 7%. Overall, 95% of patients had at least one cardinal symptom or sign of aortic stenosis (history of angina, history of congestive heart failure, or a systolic murmur); no patients had exertional syncope. Echocardiographic findings are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Findings of Participants in Accuracy Study (n= 123)

Physical examination data collection was 92% complete. The general internist assessed 114 participants, and the third-year resident assessed 112; all participants were assessed by at least one examiner. The two major reasons for incomplete examinations were discharge of the patient from the hospital and unavailability of the study physician.

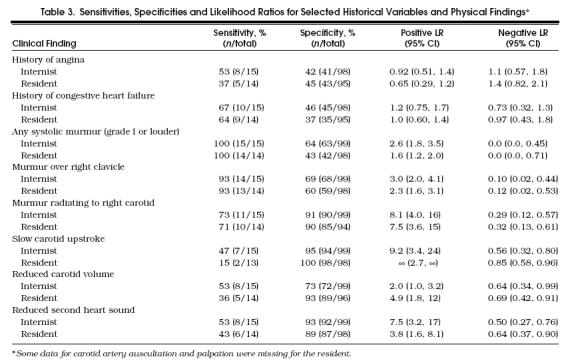

The accuracies of selected historical and physical findings are listed in Table 3. The findings with the lowest negative LRs (“rule-out” findings) were absence of murmur (negative LR 0.0 for both examiners) and absence of murmur radiating to the right clavicle (negative LR 0.10 –0.12). The findings with the highest positive LRs (“rule-in” findings) were slow upstroke of the carotid artery (positive LR 9.2–∞) and murmur radiating to the right carotid artery (positive LR 7.5 –8.1). A history of angina or congestive heart failure had no value for ruling in or ruling out aortic stenosis.

Table 3.

Sensitivities, Specificities and Likelihood Ratios for Selected Historical Variables and Physical Findings*

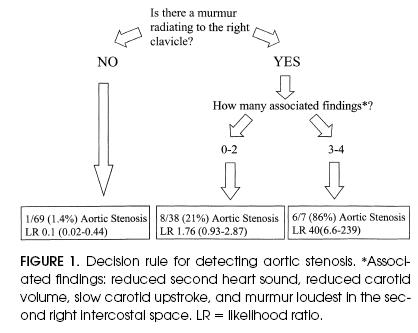

Prediction Rule

According to the general internist's examinations (Figure 1), absence of a murmur over the right clavicle effectively ruled out aortic stenosis (LR 0.10; 95% CI 0.02, 0.44; probability of aortic stenosis 1/69 [1.4%]). The presence of zero to two associated findings had an LR of 1.8 (95% CI 0.93, 2.9; probability of aortic stenosis 8/38 [21%]). The presence of three or four associated findings effectively ruled in aortic stenosis (LR 40; 95% CI 6.6, 240; probability of aortic stenosis 6/7 [86%]). Corresponding LRs (and 95% CIs) for the third-year resident were as follows: murmur over right clavicle, 0.12 (0.02, 0.53); zero to two associated findings, 1.8 (1.1, 2.6); and three or four associated findings, ∞ (4.0, ∞). There was no difference in the accuracy results between the resident and the staff internist (2p = 0.16).

Figure 1.

Decision rule for detecting aortic stenosis. *Associated findings: reduced second heart sound, reduced carotid volume, slow carotid upstroke, and murmur loudest in the second right intercostal space. LR = likelihood ratio.

Both examiners failed to detect a murmur over the right clavicle in a 90-year-old patient with a peak aortic gradient of 19 mm Hg, a calculated aortic valve area of 0.8 cm2, and a grade III left ventricle. The patient was admitted with New York Heart Association class IV dyspnea and pulmonary edema on the chest radiograph.

Reliability Study

Of the 38 participants, 55% were male, median age was 69.5 years, and major valvular lesions on echocardiography were found in 29%. The major valvular lesions were moderate or severe aortic stenosis in 3 patients, moderately severe to severe mitral regurgitation in 5, severe tricuspid regurgitation in 2, and severe aortic insufficiency in 1. Data collection was 88% complete because not all study physicians could examine each participant before hospital discharge.

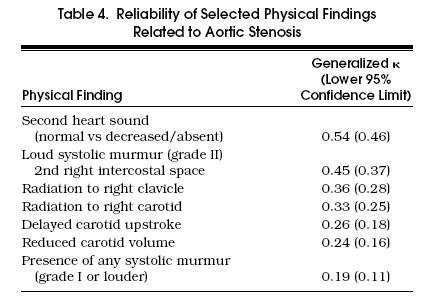

The generalized κ coefficients are listed in Table 4. The most reliable findings were reduced intensity of the second heart sound (κ = 0.54) and presence of a loud (grade II) murmur in the second right intercostal space (κ = 0.45). The least reliable finding was the presence of any systolic murmur, grade I or louder (κ = 0.19).

Table 4.

Reliability of Selected Physical Findings Related to Aortic Stenosis

DISCUSSION

We found that a prospectively evaluated bedside clinical prediction rule accurately ruled in and ruled out moderate or severe aortic stenosis, and that individual findings for the prediction rule could be elicited with fair to moderate reliability by general medical staff and residents.

Our accuracy results compare favorably with those of studies using cardiologist examiners. Our prediction rule was derived from a study that used senior cardiology trainees as examiners, in which the presence of four associated findings had an LR of 8.0.4 In this study the corresponding LR was 40 to ∞.

Our reliability results also compare favorably with those of studies using cardiologist examiners. We observed moderate reliability for assessing second heart sound intensity and presence of a grade II murmur. In previous studies, the reliability of cardiologist examiners regarding the presence of a grade II murmur was fair,16 while the reliability of assessing second heart sound intensity was poor.17 We believe that our explicit criteria for conducting the examinations improved their reliability.

Our study had several methodologic strengths.18 First, the physical examinations were independent of the echocardiographic assessments. Second, the population included an appropriate spectrum of patients with cardinal symptoms or signs of aortic stenosis, as well as patients with potentially confusing clinical conditions such as aortic sclerosis, mitral regurgitation, or tricuspid regurgitation. Finally, we prospectively studied consecutive participants with 88% to 92% complete data collection.

One potential limitation in the accuracy study was that study physicians obtained a focused cardiac history prior to the physical examination. We doubt that knowledge of the patients' symptoms significantly influenced the examinations, because patients had nonspecific clinical histories (e.g., angina or congestive heart failure), which were not useful for predicting aortic stenosis.

There are some potential limitations to generalizing our results. First, the study population consisted of medical and cardiology inpatients, most of whom had cardiac symptoms, so the 17% prevalence of aortic stenosis is higher than would be expected in an unselected elderly population. In previous studies the prevalence of moderate or severe aortic stenosis was 5% in an unselected elderly population,19 and 6% to 20% in selected elderly populations.9, 20, 21 We suspect that the prediction rule would be at least as accurate in a less selected population, because there would be a greater number of obviously normal patients, so the specificity of the prediction rule would improve.18 However, the prevalence (pretest probability) of aortic stenosis would be lower in a less selected population, so clinicians could expect lower posttest probabilities when using the prediction rule.

A second limitation relates to the generalizability of our results to other physicians. Our study physicians were motivated volunteers who used a standardized physical examination. Examinations may be less reliable and accurate if conducted by less motivated clinicians conducting unstandardized examinations. However, our protocol was easily learned in the time it would take to conduct one bedside teaching session (30 minutes), and we have shown that the individual findings can be elicited with fair to moderate reliability, and that the prediction rule can be used accurately by an internist and a medical resident. (The complete protocol is available on request from the corresponding author.)

A third limitation is the study sample size, which was intended to provide a reasonably narrow confidence interval for the negative LR, to rule out aortic stenosis. By contrast, the confidence interval for the positive LR, to rule in aortic stenosis is very wide, so we are less certain of the ability of the prediction rule to rule in aortic stenosis. This lack of certainty is of less clinical importance because we expect that clinicians would routinely order confirmatory echocardiography when the physical examinations rules in aortic stenosis, so the potential adverse consequences of a false-positive examination are minimal.

A final limitation is that we did not study rarer clinical findings such as exertional syncope,22 apical carotid delay,23 or peaking of murmur intensity in mild to late systole.9 Clinicians should search for these rarer findings because their presence should prompt further investigation for aortic stenosis. We also did not study the role of other physical findings that may indicate an alternative valvular diagnosis, such as the effect of quiet inspiration, squatting to standing, or the Valsalva maneuver.24, 25 Finally, we did not examine the contribution of the chest radiograph or the electrocardiogram.4, 26 Future studies could examine the contribution of these variables to the assessment of patients with indeterminate physical examinations.

In summary, we found that a prospectively evaluated bedside clinical prediction rule accurately ruled in and ruled out moderate or severe aortic stenosis, and that individual findings for the prediction rule could be elicited with fair to moderate reliability by general medical staff and residents. The absence of murmur radiation to the right clavicle effectively ruled out aortic stenosis, whereas the presence of three or four associated findings, slow carotid artery upstroke, reduced carotid artery volume, maximal murmur intensity at the second right intercostal space, and reduced or absent second heart sound, effectively ruled in aortic stenosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. S. Radhakrishan, A. Woo, M. Morgan, and G. Chua for participating in the reliability study and Dr. George Tomlinson for his assistance with the analysis of paired diagnostic test data.

References

- 1.Detsky AS, Abrams HB, McLaughlin JR, et al. Predicting cardiac complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1:211–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02596184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roldan CA, Shively BK, Crawford MH. Value of the cardiovascular physical examination for detecting valvular heart disease in asymptomatic subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:1327–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etchells EE, Bell C, Robb KV. Does this patient have an abnormal systolic murmur? JAMA. 1997;277:564–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoagland PM, Cook EF, Wynne J, Goldman L. Value of noninvasive testing in adults with aortic stenosis. Am J Med. 1986;80:1041–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paauw DS, Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Carline JD, Ramsey PG. Ability of primary care physicians to recognize physical findings associated with HIV infection. JAMA. 1995;274:1380–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKillop GM, Stewart DA, Burns JMA, Ballantyne D. Doppler echocardiography in elderly patients with ejection systolic murmurs. Postgrad Med J. 1991;61:1059–61. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.67.794.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinstein AR, Kramer MS. Clinical biostatistics, LIII: the architecture of observer/method variability and other types of process research. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;28:551–63. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1980.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spodick DH, Kerrigan AT, de la Paz LR, Shahamatpour A, Kino M. Clavicular auscultation. Preferential clavicular transmission and amplification of aortic murmurs. Chest. 1976;70:337–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.70.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronow WS, Kronzon I. Prevalence and severity of valvular aortic stenosis determined by Doppler echochardiography and its association with echocardiographic and electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and physical signs of aortic stenosis in elderly persons. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:776–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90542-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constant J. Bedside Cardiology. 3rd. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Company; 1985. pp. 38–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd ed. Toronto, Ont: John Wiley and Sons; 1981. pp. 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centor RM. Estimating confidence intervals of likelihood ratios. Med Decis Making. 1992;12:229–33. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9201200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leisenring W, Pepe MS, Longton G. A marginal regression modeling framework for evaluating medical diagnostic data. Stat Med. 1997;16:1263–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970615)16:11<1263::aid-sim550>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:763–70. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90128-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taranta A, Spagnuolo M, Snyder R, Gerbarg DS, Hofler JJ. Auscultation of the heart by physicians and by computer. 3rd. New York, NY: McMillan Co; 1964. Data Acquisition and Processing in Biology and Medicine; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raftery EB, Holland WW. Examination of the heart: an investigation into variation. Am J Epidemiol. 1967;85:438–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Sackett DL. Users' Guide to the Medical Literature, III: How to use an article about a diagnostic test, A: Are the results of the study valid? JAMA. 1994;271:389–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.5.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkila J, Tilvis R. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1220–5. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90249-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight PV, Martin BJ, Ballantyne D. Echocardiographic diagnoses in elderly patients with systolic murmurs and cardiac disease. Age Ageing. 1986;15:169–73. doi: 10.1093/ageing/15.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu M, McHaffie DJ. Nonspecific systolic murmurs: an audit of the clinical value of echocardiography. N Z Med J. 1993;106:54–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forssell G, Jonasson R, Orinius E. Identifying severe aortic valvular stenosis by bedside examination. Acta Med Scand. 1985;218:397–400. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb08864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chun PKC, Dunn BE. Clinical clue of severe aortic stenosis. Simultaneous palpation of the carotid and apical impulses. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2284–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.142.13.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothman A, Goldberger AL. Aids to cardiac auscultation. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:346–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-3-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lembo NJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Crawford MH, O'Rourke RA. Bedside diagnosis of systolic murmurs. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1572–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806163182404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddleman EE, Frommeyer WB, Jr, Lyle DP, Bancroft WH, Jr, Turner ME. Critical analysis of clinical factors in estimating severity of aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31:687–95. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]