Abstract

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supports 40 Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH 2010) community coalitions in designing, implementing, and evaluating community-driven strategies to eliminate health disparities in racial and ethnic groups. The REACH 2010 logic model was developed to assist grantees in identifying, documenting, and evaluating local attributes of the coalition and its partners to reduce and eliminate local health disparities. The model emphasizes the program's theory of change for addressing health disparities; it displays five distinct stages of evaluation for which qualitative and quantitative measurement data are collected. The CDC is relying on REACH 2010 grantees to provide credible evidence that explains how community contributions have changed conditions and behaviors, thus leading to the reduction and elimination of health disparities.

Introduction

Established in 1999, Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH 2010) is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) cornerstone initiative aimed at eliminating disparities in the health status of African Americans, Alaska Natives, American Indians, Asian Americans, Hispanics, and Pacific Islanders. The CDC supports 40 REACH 2010 community coalitions in designing, implementing, and evaluating community-driven strategies to eliminate health disparities in one or more of six priority areas: breast and cervical cancer screening and management, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, immunizations, and infant mortality (1). Local strategies incorporate community-based participatory approaches designed to reduce risk factors and the prevalence and impact of chronic diseases. Interventions include individual, family, provider, or community activities focused on the prevention, detection, treatment, and management of one or more of the priority areas. In addition to local evaluation plans, the CDC has a national evaluation strategy for cross-site evaluation of grantee programs to identify and assess successful community partnerships and to determine whether local choices of strategies and interventions produced desired changes in health disparities among racial and ethnic groups. The national evaluation plan has two components: process evaluation and outcome evaluation. The process evaluation collects data to gain insights about coalition characteristics and actions that affect the implementation of the local REACH 2010 program (2). The outcome evaluation uses surveillance data to determine the impact of local interventions that are implemented to reduce health disparities in racial and ethnic groups (3). In an effort to provide the REACH 2010 grantees with a clear road map of what is ahead, the CDC developed the REACH 2010 logic model to identify anticipated processes and outcomes and assist communities with evaluation.

A program logic model is defined as a picture of how an organization does its work — the theory and assumptions underlying the program (4). The program logic model links outcomes (both short term and long term) with program activities or processes and the theoretical assumptions and principles of the program (4). The logic model helps create a shared understanding of the program's goals and methodology, relating activities to projected outcomes (4). The basic components of a logic model include factors (resources that potentially enable or limit program effectiveness); activities (techniques, tools, events, and actions of the planned program); outputs (the direct results of program activities); outcomes (changes in attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, skills, status, or level of functioning); impacts (organization-level, community-level, or system-level changes) (4); and relevant external influences (5). Variations of the logic model have different names, and these variations are all related to program theory (5). Logic models come in different shapes and sizes and may be a combination of various program logic models (6-8).

This article describes the logic model developed for REACH 2010 that visually depicts the program's theory of change (5) for addressing health disparities in local communities. The model is theoretically based and includes the conditions being addressed, activities used to address these conditions, and the expected outcomes of the activities (4). The REACH 2010 logic model is designed to test the effectiveness of multisite community-based programs in improving the health of racial and ethnic populations. The logic model provides communities with a plausible and sensible model of how the program will work to solve identified problems (5).

The REACH 2010 logic model illustrates how a coalition could theoretically produce the desired local health disparity reductions and impacts in racial and ethnic groups. It focuses on the logical approaches of a community coalition that organizes to learn the context of, causes of, and solutions for local health disparities and is prepared to take actions to reduce and eliminate the disparities. It also is a tool used to explain and illustrate program concepts and approaches for key stakeholders. As such, it has assisted REACH 2010 communities in identifying, documenting, and evaluating local attributes in the reduction and elimination of community health disparities.

Elements of the REACH 2010 Logic Model

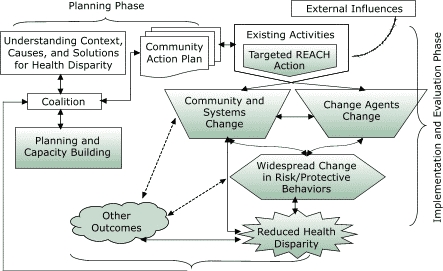

The REACH 2010 logic model (Figure) is a theory model that links theoretical constructs together to explain the underlying assumptions of the program. The theory model is appropriate for complex, multifaceted initiatives aimed at entire communities (e.g., community coalition partnerships addressing chronic disease prevention within the community) (8). The REACH 2010 logic model helps prioritize aspects of the program that are most critical for tracking and reporting, and it also helps identify data needed for monitoring and improving the program.

Figure.

Logic model for Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH 2010).

Community health initiatives are often shaped by a public health framework that uses technical assistance and evaluation to help build local capacities for addressing identified community concerns (9). The CDC used the espoused theory of action for its framework. Delineating an espoused theory of action involves identifying critical assumptions, conceptual gaps, and information gaps (10). The conceptual gaps are filled by logic, discussion, and policy analysis. The information gaps are filled by evaluation research (10). This approach was used to develop the REACH 2010 logic model; that is, the stakeholders developed a framework based on their perceptions of how community coalitions and their partners function (10) to reduce health disparities. During technical assistance workshops, the CDC introduced the REACH 2010 logic model to grantees in their 1-year planning phase and again during the second through fourth years of their cooperative agreements. The CDC discussed each component of the logic model and perceptions of events that are likely to occur in a community addressing health disparities.

Planning

The REACH 2010 program logic rests on several related but distinct components in two separate phases. The first phase, planning, includes the following components: 1) a community coalition forms or expands its network; 2) the coalition develops, plans, and builds capacity; 3) the coalition meets regularly to gain an understanding of the context of, causes of, and solutions for health disparity; and 4) a Community Action Plan (CAP) — an intervention strategy designed to reduce levels of disparity within the community — is produced. The local evaluation plan is incorporated in the CAP and often includes the contract services of an evaluator. Such expertise is sought from universities, evaluation organizations, private practice evaluators, and others. The CAP takes into account all other activities occurring in the environment that might affect the level of health disparities in a specific community. The actions taken by the REACH 2010 coalition should be aligned to coordinate with other interventions and thereby contribute to a coordinated community initiative aimed at eliminating health disparities and achieving other community outcomes.

Implementation and Evaluation

The second phase, implementation and evaluation, includes the following components: 1) the implementation of REACH 2010 targeted activities and the assessment and acknowledgment of existing activities that are aimed at the community; 2) the implementation of targeted actions that are thought likely to bring about changes in the community and systems or changes among change agents; 3) change in widespread risk or protective behaviors in the community of focus; 4) reductions in health disparities; 5) other or unexpected outcomes; and 6) the examination and recognition by the coalition of external influences on the community. It is important to note that in the REACH 2010 logic model, all arrows point in both directions. This aspect of the model allows for flexibility and inevitable self-correction as new conditions occur and new knowledge is attained and incorporated into the CAP. It is important to examine the external conditions under which a program is implemented and how those conditions influence outcomes (5).

The REACH 2010 logic model identifies key measurement and evaluation stages. The following is a description of each evaluation stage and related examples of REACH 2010 activities and evaluation measures.

Stage 1: capacity building

Many REACH 2010 community-based coalitions were formed or expanded to address health issues. These coalitions are primarily driven by the residents of the community at every stage, including planning, implementation, and evaluation. In the REACH 2010 logic model, capacity building refers to the readiness or ability of the coalition and its members to take action aimed at changing risk or protective behaviors and transforming community conditions and systems so that a supportive environment exists to sustain behavior changes over time. Capacity building among REACH 2010 grantees includes establishing traditional public health partnerships among voluntary organizations (6), a national nurses' association (11), a health care delivery system (11), family services (12), clinicians (13), consumers (13), social service agencies (13), and the Indian Health Board (14), as well as nontraditional partnerships such as those between faith-based national organizations and local institutions (6,13), a quality assurance foundation (6), a housing authority (15), and a gardening group (15) that are supportive of improving the health and well-being of the community.

Stage 2: targeted actions

Targeted actions or interventions are planned, identifiable, and discrete activities included in a program to produce change in the population of focus (16). The REACH 2010 targeted actions are activities that make up the intervention that is believed to bring about desired effects. Interventions include activities such as distribution of the Gold Card, a patient mini-record for individuals with diabetes (17); use of health advocates to enroll pregnant individuals in a prenatal care system (18); formal continuing medical education seminars on cervical cancer (19); and media education campaigns (20).

Stage 3: community and systems change

Community and systems change refers to changing at-risk conditions by altering the environmental context within which individuals and groups behave, for example, by implementing a neighborhood farmers' market (15), establishing community walking groups (15), and offering immunization education in the supplemental nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and child care and Head Start programs (21). Change among change agents refers to documented changes in knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors among a community's influential individuals or groups with the intent of diffusing similar changes to a broader community population. The change agents might include community health advocates and advisors, lay health workers, or peer health promoters who promote community-level awareness of chronic diseases and their related risk factors (12); beauty and barbershop operators who help disseminate educational information throughout the community on the prevention of chronic diseases (22); ministers, physicians, and nurses (6); and parents who keep their children immunized (21).

Stage 4: widespread change in risk or protective behaviors

Widespread change in risk or protective behaviors occurs when a significant proportion of individuals in the identified community changes behaviors that are linked to health status. Examples of changes in protective behaviors in REACH 2010 communities include an increase in immunization rates among children older than 18 months who were enrolled in an intervention program, from 32% at enrollment to 74% at the 1-year follow-up (21), and an increase in Papanicolaou test use among Vietnamese women in an intervention group, from 62.1% to 76.9% (20).

Stage 5: health disparity reduction

Health disparity reduction occurs when there is a narrowing of the gap in health status between a racial or ethnic group and an appropriate referent group; for REACH 2010, the referent group is the general population (23). In addition to the examples provided in the previous paragraph, the actions of a REACH 2010 diabetes coalition have led to better health among African Americans with diabetes; between 1999 and 2002, the gap between African Americans and whites in rates of annual hemoglobin A1c testing, which is used to measure blood glucose control, was virtually eliminated in their communities (24).

Measuring Performance

Measuring a program's performance is a way to address accountability or to collect information that helps stakeholders understand how the program is working (5), both of which contribute to more informed decision making about improvements needed to enhance the quality of the program. The logic model is a tool that can guide and assess the program implementation and program input (2). In the REACH 2010 logic model, evaluation stages 1 through 5 are being monitored. The connecting lines are hypothesized linkages or causal relationships that require in-depth study to determine and explain what happened (2). The arrows in the REACH 2010 logic model and the measurement of the linkages provide information on how community actions or activities are presumed to contribute to reducing or eliminating health disparities (2).

The CDC provides the REACH 2010 grantees with assistance in documenting community-level changes, both qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative evaluation emphasizes describing the process and understanding social phenomena and other data that influence the direction of the program. Process-oriented evaluation promotes better understanding of program implementation, the causal events leading to change, and the program components that most influence change (2). The REACH 2010 grantees document qualitative data related to the logic model stages 1 through 3 in the REACH Information Network (REACH IN) system (ORC Macro International, Calverton, Md). The REACH IN system allows grantees at the local level to perform data entry, storage, and retrieval and to produce graphs and reports. These data also are used by the CDC to monitor the types of local activities used to address health disparities.

By using epidemiological methods to establish estimates of the programs' effects, the quantitative data are systematically and uniformly collected and used to assess impact (25). The annual REACH Risk Factor Survey data are collected by a CDC contractor, a National Organization for Research (NORC) at the University of Chicago (23). The REACH 2010 Risk Factor Survey includes questions related to the respondents' health status; health care access; self-reported body measurements; tobacco use; awareness of hypertension, cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes and diabetes care; and receipt of preventive services (23). The CDC analyzes these data and prepares and disseminates reports (26). Data files are also issued to grantees for local analysis and interpretation. REACH 2010 grantees use local evaluation plans for more detailed and precise measurement of the program, with an eye toward obtaining data that meet local requirements. The use of multiple methods of data collection, often referred to as triangulation, can strengthen the validity of findings if results produced by different methods are congruent (25).

Discussion and Conclusions

The REACH 2010 logic model is a tool that illustrates the theoretical approach and perspective of 40 community-based programs addressing health disparities in racial and ethnic groups. Using the REACH 2010 logic model is beneficial because it 1) provides an opportunity to communicate and to share stakeholders' ideas and assumptions, 2) establishes a common perception or understanding of the coalitions' probable actions or experiences for addressing health disparities, 3) supports the program design and identifies linkages among program elements, 4) identifies a set of key performance measurement points and evaluation issues, and 5) assists with data collection for local use (5).

Measuring the achievement of the goal to reduce or eliminate disparities is an essential precept of the REACH 2010 logic model. Data collected by the REACH 2010 Risk Factor Survey and the REACH IN system will continue to be used to measure national progress toward the goal. The analysis of national data is necessary to ascertain predictors of the REACH 2010 logic model. The CDC is also relying on REACH 2010 coalitions to provide credible evidence to explain how targeted local actions contribute to changes in conditions and behaviors that support the elimination or reduction of health disparities.

The REACH 2010 logic model represents the initial theoretical framework of the program. We recognize that since 1999, additional planning and refinement of the model have occurred at the community level (4). As the REACH 2010 logic model process continues to unfold, the stakeholders responsible for implementing the model will be involved in its evaluation. They will assess whether the model has accomplished its goal of capturing the unique perspectives and community processes that guide community coalitions, that is, determining the way and the conditions under which local coalitions actually work to achieve their goals. Lessons learned from REACH 2010 will provide needed practice-based evidence to inform the next generation of community-based programs working to reduce health disparities.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend special thanks to Marshall W. Kreuter, PhD, and Robert (Bobby) Milstein, MPH, for their contributions to the development of the REACH 2010 logic model.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.

Suggested citation for this article: Tucker P, Liao Y, Giles WH, Liburd L. The REACH 2010 logic model: an illustration of expected performance. Prev Chronic Dis [serial online] 2006 Jan [date cited]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/jan/05_0131.htm

Contributor Information

Pattie Tucker, Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Email: ptucker1@cdc.gov, 4770 Buford Hwy, NE, Mail Stop K-30, Atlanta, GA 303411, Phone: 770-488-5445.

Youlian Liao, Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

Wayne H Giles, Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

Leandris Liburd, Division of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

References

- 1.Giles WH, Tucker P, Brown L, Crocker C, Jack N, Latimer A, et al. Racial and ethnic approaches to community health (REACH 2010): an overview. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S5–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi PH, Freeman HE, editors. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 5th ed. SAGE Publications; Newbury Park (CA): 1993. pp. 162–165. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi PH, Freeman HE, editors. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 5th ed. SAGE Publications; Newbury Park (CA): 1993. pp. 234–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Logic model development guide [monograph online] W.K. Kellogg Foundation; Battle Creek (MI): 2004. [cited 2005 Jun 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub3669.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB. Logic models: a tool for telling your program performance story. Eval Program Plann 1999;22:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouad MN, Nagy MC, Johnson RE, Wynn TA, Partridge EE, Dignan M. The development of a community action plan to reduce breast and cervical cancer disparities between African American and white women. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S53–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darrow WW, Montanea JE, Fernandez PB, Zucker UF, Stephens DP, Gladwin H. Eliminating disparities in HIV disease: community mobilization to prevent HIV transmission among Black and Hispanic young adults in Broward County, Florida. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S108–S116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Evaluation handbook [monograph online] Battle Creek (MI): W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 1998. [cited 2005 Jun 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub770.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin RK, Kaftarian SJ, Jacobs NF. Empowerment evaluation at federal and local levels: dealing with quality. In: Fetterman DM, Kaftarian SJ, Wandersman A, editors. Empowerment evaluation: knowledge and tools for self-assessment & accountability. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks (CA): 1996. pp. 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patton MQ. Utilization-focused evaluation: the new century text. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks (CA): Ons. 1997. pp. 221–227.The program's theory of action; [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanjasiri SP, Tran JH, Kawgawa-Singer M, Foo MA, Foong HL, Lee SW, et al. Exploring access to cancer control services for Asian-American and Pacific Islander communities in Southern California. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S14–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieffer EC, Willis SK, Odoms-Young AM, Guzman JR, Allen AJ, Two Feathers J, et al. Reducing disparities in diabetes among African American and Latino residents of Detroit: the essential role of community planning focus groups. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S27–S37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metayer N, Jean-Louis E, Madison A. Overcoming historical and institutional distrust: key elements in developing and sustaining the community mobilization against HIV in the Boston Haitian community. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S46–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.English KC, Wallerstein N, Chino M, Finster CE, Rafelito A, Adeky S, et al. Intermediate outcomes of a tribal community health public health infrastructure assessment. Ethn Dis. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S61–S69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeBate R, Plescia M, Joyner D, Spann L. A qualitative assessment of Charlotte REACH: an ecological perspective for decreasing CVD and diabetes among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S77–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi PH, Freeman HE, editors. Programs, policies, and evaluations. 5th ed. Newbury Park (CA): SAGE Publications; 1993. pp. 2–55.Evaluation: a systematic approach; [Google Scholar]

- 17.King MG, Jenkins C, Hossler C, Carlson B, Magwood G, Hendrix K. People with diabetes: knowledge, perceptions, and applications of recommendations for diabetes management. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S128–S133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunte HE, Turner TM, Pollack HA, Lewis EY. A birth records analysis of the Maternal Infant Health Advocate Service program: a paraprofessional intervention aimed at addressing infant mortality in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S102–S107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai KQ, Nguyen TT, Mock J, McPhee SJ, Doan HT, Pham TH. Increasing Vietnamese-American physicians' knowledge of cervical cancer and Pap testing: impact of continuing medical education programs. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S122–S127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam TK, McPhee SJ, Mock J, Wong C, Doan HT, Nguyen TL, et al. Encouraging Vietnamese-American women to obtain Pap tests through lay health worker outreach and media education. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Jul;18(7):516–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Findley S, Irigoyen M, Sanchez M, Guzman L, Mejia M, Sajous M, et al. Community empowerment to reduce childhood immunization disparities in New York City. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S134–S141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKeever C, Faddis C, Koroloff N, Henn J. Wellness Within REACH: mind, body, and soul: a no-cost physical activity program for African Americans in Portland, Oregon, to combat cardiovascular disease. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S93–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao Y, Tucker P, Giles WH. Health status among REACH 2010 communities, 2001-2002. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S9–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins C, McNary S, Carlson BA, King MG, Hossler CL, Magwood G, et al. Reducing disparities for African Americans with diabetes: progress made by the REACH 2010 Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition. Public Health Rep. 2004 May-Jun;119(3):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossi PH, Freeman HE, editors. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 5th ed. Newbury Park (CA): SAGE Publications; 1993. pp. 403–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao Y, Tucker P, Okoro CA, Giles WH, Mokdad AH, Harris VB. REACH 2010 surveillance for health status in minority communities — United States, 2001-2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004 Aug 27;53(6):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]