Abstract

Transcriptional control of carbon source preferences by Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 was assessed with a pobA::lacZ fusion during growth on alternative substrates. The pobA-encoded enzyme catalyzes the first step in the degradation of 4-hydroxybenzoate, a compound consumed rapidly as a sole carbon source. If additional aromatic carbon sources are available, 4-hydroxybenzoate consumption is inhibited by unknown mechanisms. As reported here, during growth on aromatic substrates, pobA was not expressed despite the presence of 4-hydroxybenzoate, an inducer that normally causes the PobR regulator to activate pobA transcription. Growth on organic acids such as succinate, fumarate, and acetate allowed higher levels of pobA expression. In each case, pobA expression increased at the end of the exponential growth phase. Complex transcriptional regulation controlled 4-hydroxybenzoate catabolism in multisubstrate environments. Additional studies focused on the wild-type preference for benzoate consumption prior to 4-hydroxybenzoate consumption. These compounds are degraded via the catechol and protocatechuate branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway, respectively. Here, mutants were characterized that degraded benzoate and 4-hydroxybenzoate concurrently. These mutants lacked the BenM and CatM transcriptional regulators that normally activate genes for benzoate catabolism. A model is presented in which BenM and CatM prevent pobA expression indirectly during growth on benzoate. These regulators may affect pobA expression by lowering the PcaK-mediated uptake of 4-hydroxybenzoate. Consistent with this model, BenM and CatM bound in vitro to an operator-promoter fragment controlling the expression of several pca genes, including pcaK. These studies provide the first direct evidence of transcriptional cross-regulation between the distinct but analogous branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway.

Soil bacteria often degrade the components of a mixture of aromatic growth substrates in a sequential fashion. This type of ordered catabolism has been noted for strains of Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Ralstonia (1, 15, 19, 25). While reminiscent of catabolite repression, which has been well studied in some enteric and gram-positive bacteria (32, 35), the method by which the gram-negative bacterium Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 controls the preferential consumption of carbon sources remains unclear. A recent study of this strain characterized the repressive effects of succinate and acetate, as carbon sources, on the levels of certain transcripts and enzymes needed for aromatic compound degradation (8). Continued interest in regulated aromatic compound degradation stems, in part, from its potential effects on bioremediation and biotechnology (28).

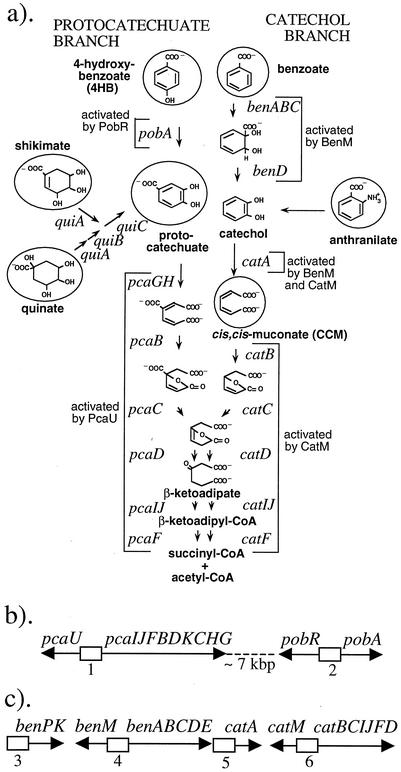

In ADP1 and in Pseudomonas putida strain PRS2000, benzoate is consumed in preference to 4-hydroxybenzoate (4HB) (15, 25). Both of these similarly structured aromatic compounds are degraded via the β-ketoadipate pathway (Fig. 1) (18). However, in P. fluorescens strains PC24 and PC18, which also degrade benzoate and 4HB through the β-ketoadipate pathway, benzoate is not the preferred carbon source (19). Strain PC24 consumes both substrates simultaneously, while PC18 degrades 4HB in preference to benzoate. Thus, there are no inherent properties of these compounds that dictate the order of their consumption.

FIG. 1.

Diverse aromatic compounds are degraded via the protocatechuate and catechol branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway in ADP1. (a) Compounds used as growth substrates in these studies are circled. Brackets mark genes whose expression is controlled by the indicated transcriptional regulators. (b) The relative positions and transcriptional directions are depicted for part of a supraoperonic chromosomal gene cluster that encodes the protocatechuate branch of the pathway (not drawn to scale). (c) A supraoperonic cluster of genes for the catechol branch is separated from the pca genes by approximately 280 kbp of chromosomal DNA. The numbered boxes represent regions of transcriptional control that are discussed in the text.

In P. putida PRS2000, the BenR transcriptional regulator is involved in the benzoate-mediated repression of 4HB degradation (7). In response to benzoate, BenR, a member of the AraC/XylS regulatory family, activates the expression of genes for benzoate degradation. In addition, BenR helps repress the expression of pcaK, the gene encoding a 4HB permease (14, 17). The decreased induction of PcaK limits the uptake of 4HB and contributes to the preferential consumption of benzoate. No BenR binding site has been identified near pcaK, and it is unclear whether BenR plays a direct or an indirect role in pca gene expression.

Compared to P. putida PRS2000, there are significant differences in the organization and regulation of genes for the β-ketoadipate pathway in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. For example, there is no BenR homolog in ADP1. Instead, BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, controls the expression of genes for the initial steps in benzoate degradation (4, 6). Furthermore, cis,cis-muconate (CCM), a metabolite of benzoate degradation (shown in Fig. 1), rather than benzoate itself, is the key inhibitor of 4HB catabolism when ADP1 grows on benzoate (15). This conclusion was drawn from the metabolic investigation of mutants. In strains blocked in benzoate catabolism that produce CCM endogenously, 4HB degradation is inhibited. This inhibition occurs despite the inability of the mutant to derive energy from the partial degradation of benzoate. In contrast, 4HB catabolism is not inhibited in mutants blocked in benzoate catabolism if the formation of CCM is prevented or delayed (15).

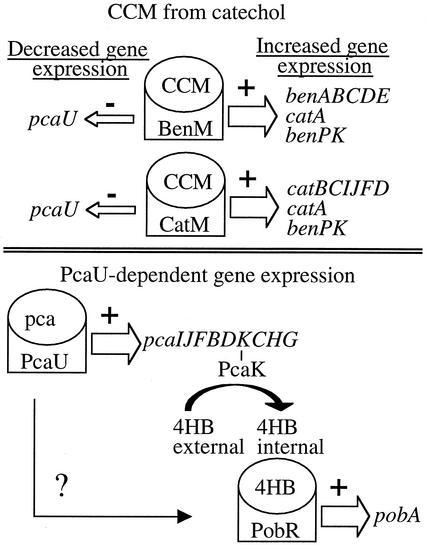

In ADP1, CCM is the key transcriptional coactivator of genes for the catechol branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway. This metabolite interacts not only with BenM but also with CatM, a second LysR-type transcriptional regulator involved in benzoate degradation (Fig. 1 and 2) (31). As described in this report, we tested the possibility that CatM and BenM inhibit 4HB catabolism during growth of ADP1 on benzoate. Initial transcriptional studies focused on pobA, whose product initiates 4HB degradation (Fig. 1). Normally, 4HB interacts with the PobR regulator to activate pobA expression (11, 12). A pobA::lacZ transcriptional fusion was used to study the effects of different growth substrates on gene expression. One goal was to determine whether the inhibition of 4HB catabolism occurs at the transcriptional level in ADP1. A second goal was to assess whether CatM and BenM bind specifically to genetic regions involved in 4HB degradation. Furthermore, we examined whether the absence of CatM and BenM in mutant strains affects 4HB catabolism. The mutants were selected for the ability to grow on benzoate without their normal transcriptional regulators (30). Collectively, these studies suggested that CatM and BenM regulate 4HB consumption when CCM is generated endogenously during growth on a preferred aromatic carbon source.

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional regulation of the β-ketoadipate pathway in ADP1. Endogenously generated CCM interacts with the regulatory proteins CatM and BenM to regulate gene expression as shown. BenM additionally responds to benzoate to activate benABCDE and catA expression (not depicted). BenM- or CatM-mediated repression of pcaU expression should prevent or lower PcaU-activated gene expression (shown at the bottom). A thick (+) or thin (−) open arrow indicates that the adjacent regulator, together with its cognate effector, increases or decreases gene expression, respectively. The question mark indicates the untested possibility that PcaU regulates additional genes that affect pobA expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All of the Acinetobacter strains listed in Table 1 were derived from Acinetobacter sp. (formerly calcoaceticus) strain BD413, also designated ADP1 (20). Escherichia coli DH5α (Gibco-BRL) was used as a plasmid host. Bacterial cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (33) or minimal medium at 37°C as previously described (34). Carbon sources were added to minimal medium at a final concentration of 4 mM. Liquid cultures were aerated on platform shakers.

TABLE 1.

Acinetobacter strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ADP1 | Wild type (also designated BD413); uses 4HB or benzoate as sole carbon source | 20 |

| ADP4003 | pobA430::lacZ; cannot use 4HB as sole carbon source | 11 |

| ACN146 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5146; benA point mutation may allow CatM to activate ben gene expression for growth on benzoate | 6 |

| ACN147 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5147; point mutation increases benA promoter strength to allow growth on benzoate | 6 |

| ACN277 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5147 ΔcatM5293 amplicon 5277; amplification of a 30-kbp chromosomal region containing the cat genes allows growth on benzoate as sole carbon source | 30 |

| ACN282 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5147 ΔcatM5293 amplicon 5282; amplification of a 100-kbp chromosomal region containing the cat genes allows growth on benzoate as sole carbon source | 30 |

| ACN283 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5147 ΔcatM5293 amplicon 5283; amplification of a 38-kbp chromosomal region containing the cat genes allows growth on benzoate as sole carbon source | 30 |

| ACN284 | benM::ΩS4036 benA5147 ΔcatM5293 amplicon 5284; amplification of a 50-kbp chromosomal region containing the cat genes allows growth on benzoate as sole carbon source | 30 |

| ISA36 | benM::ΩS4036; loss of BenM prevents growth on benzoate as sole carbon source | 6 |

β-Galactosidase (LacZ) assays.

Prior to inoculation of cultures for enzyme assays, ADP4003, with a chromosomal pobA::lacZ transcriptional fusion, was grown and transferred in liquid medium for 2 days with the same growth substrate intended for the final culture. At a time point designated time zero, 0.5 ml of the starting culture was used to inoculate one flask containing 20 ml of fresh medium. A second flask containing 20 ml of the same medium with 10 μM 4HB was similarly inoculated. These cultures were incubated, and samples were taken at various time points to assess growth by determining optical density at 600 nm and to measure enzyme activity. Cells were lysed with chloroform and sodium dodecyl sulfate, and β-galactosidase (LacZ) activities were determined as described by Miller (24). For each experimental condition, at least nine separate cultures were grown and assayed.

Gel retardation assays.

A double-stranded DNA fragment with the pcaU operator-promoter region was radiolabeled as previously described (26). The PCAUO/P-F and PCAUO/P-R primers (see Fig. 5; purchased from Genosys), after being 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega), were used to amplify a 291-bp DNA fragment by PCR. Plasmid pZR18 was used as the template DNA (16). The labeled fragment was purified following separation by 5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (26).

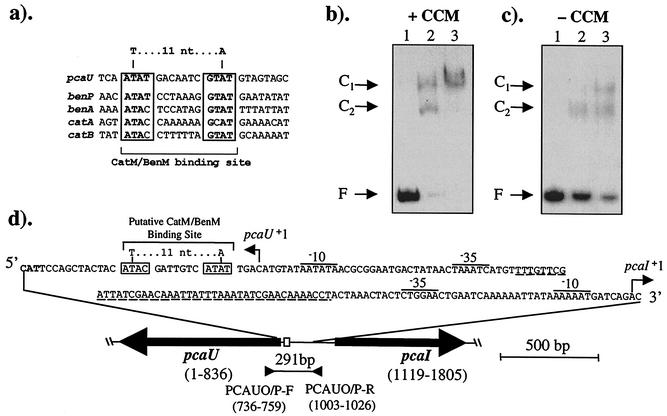

FIG. 5.

Interactions of CatM with the pcaU-I regulatory region. (a) Immediately downstream of the pcaU transcriptional start site, a sequence, ATAT-7 nucleotides-GTAT, matches the LysR-type binding consensus sequence T-11 nucleotides-A within a small region of dyad symmetry. This sequence is aligned with those that bind, or are proposed to bind, CatM and/or BenM upstream of the ben and cat promoters that they activate. (b) Gel retardation assays with CatM and labeled pcaU DNA containing CCM. (c) Assays in the absence of CCM. The mobility of free DNA (F) is shown in reaction mixtures that contained no protein (lanes 1). The binding reaction mixtures contained 100 or 200 ng of CatM in lanes 2 and 3, respectively. The retarded mobility of fragments at positions C1 and C2 presumably results from the binding of CatM to form protein-DNA complexes. (d) Recently identified pcaU-I regulatory sequences are indicated, with a PcaU binding site underlined (29). Numbers correspond to the DNA sequence with GenBank accession number L05770 such that 1 is the last position of the stop codon of the complementary sequence of pcaU. The proposed CatM/BenM binding site (box) is shown relative to the 291-bp fragment amplified by PCR with the PCAUO/P primers and used in the gel retardation assays.

The CatM and BenM proteins were purified as previously described (5). Except where noted otherwise, 200 ng of one of the regulatory proteins was used in the binding reaction mixture. The incubation buffer for the binding reactions contained 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH. 8.0. Sonicated salmon sperm DNA was used as a nonspecific competitor at a final concentration of 0.05 mg/ml. In competition studies, unlabeled DNA fragments were used with the labeled fragment to verify the specificity of CatM and BenM binding. For use as a specific competitor, a pcaU DNA fragment was generated by PCR as described above except that the primers were not labeled with 32P. In competition studies, this fragment was added to a molar excess of the labeled probe of up to 100-fold as previously described (36). Binding reactions were initiated by mixing 5 to 1,000 ng of CatM or BenM with 1,000 cpm of the 32P-labeled pcaU fragment (approximately 10 nM) in the presence or absence of 1 mM CCM. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min before the DNA-protein complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis (26). When CCM was included in the binding reaction mixtures, it was also added to the polyacrylamide gel and to the running buffer at a final concentration of 1 mM.

Metabolite monitoring by HPLC.

To monitor metabolism, cultures were grown in minimal medium with 1 mM benzoate and 1 mM 4HB. At several time points, 1-ml culture samples were centrifuged to pellet cells. Any cells remaining in the supernatant fractions were removed by passage through a low-protein-binding, 0.22-μm-pore-size syringe filter (from MSI). A 10-μl sample of the filtrate was analyzed on a C18 reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Elution at a rate of 0.8 ml/min was carried out with 30% acetonitrile and 0.1% phosphoric acid, and the eluant was monitored by UV detection at 210 nm. Under these conditions, the retention times of benzoate, catechol, 4HB, and CCM were 13.5, 7.3, 6.0, and 4.6 min, respectively. Peak areas corresponding to standards and experimental samples were calculated with the ValuChrom software package (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Carbon source-dependent regulation of pobA expression.

DiMarco and colleagues used an Acinetobacter strain, ADP4003, with a chromosomal pobA::lacZ transcriptional fusion to study the activation of pobA expression by PobR in response to 4HB (11). The disruption of pobA in this strain prevents 4HB from serving as a carbon source. In our studies, pobA expression in ADP4003 was assessed during growth on 10 different substrates. We tested whether the inhibition of 4HB catabolism that occurs in the presence of preferred carbon sources reflects carbon source-dependent regulation of pobA transcription. For each growth substrate, two cultures were inoculated in the same fashion. To one of the two cultures, 10 μM 4HB was added to induce pobA::lacZ expression. As previously reported, with succinate as the carbon source, 10 μM 4HB yields approximately 90% of the maximal β-galactosidase (LacZ) activity that can be achieved with 1 mM 4HB (11). In our investigations, concentrations of 100 μM to 1 mM 4HB reduced the growth rate of ADP4003 (data not shown). Therefore, 10 μM 4HB was selected as an inducer concentration that would enable high-level pobA::lacZ expression while not significantly altering the growth rate of ADP4003. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in samples taken at intervals of 1 to 3 h.

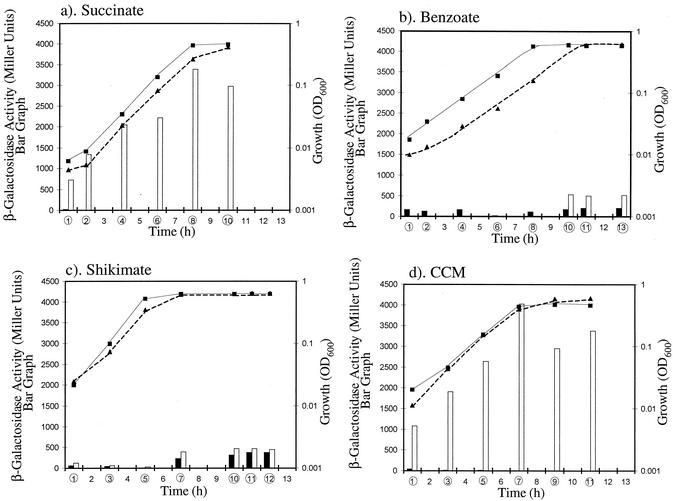

With succinate as the carbon source, there was no significant β-galactosidase activity in the absence of 4HB, the inducer needed for PobR-activated pobA expression. As expected, the presence of 4HB induced high levels of β-galactosidase activity and the pobA::lacZ fusion was expressed during all phases of growth (Fig. 3a). In contrast, with benzoate as the carbon source, 4HB did not induce high-level pobA::lacZ expression (Fig. 3b). Transcriptional regulation appears to be the major factor in determining the timing of 4HB catabolism in the presence of alternative carbon sources. This conclusion was further supported by studies with carbon sources, such as shikimate, that are degraded via the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway (Fig. 1). Shikimate, like benzoate, is consumed by the wild-type strain in preference to 4HB (15). Since both shikimate and 4HB are initially converted to protocatechuate, the cellular uptake of 4HB and/or its hydroxylation by the PobA enzyme must be prevented. Consistent with this inference, PobR and 4HB were unable to activate pobA expression in ADP4003 (Fig. 3c).

FIG. 3.

Expression of a pobA::lacZ chromosomal transcriptional fusion in strain ADP4003 grown in minimal medium with succinate (a), benzoate (b), shikimate (c), or CCM (d) as the sole source of carbon and energy. β-Galactosidase (LacZ) activity and growth were assessed at several times after cultures were inoculated. In each experiment, the times at which samples were tested are circled. Dashed lines with triangles and solid lines with squares indicate growth of cultures with and without 4HB provided as an inducer, respectively. Open and closed bars correspond to β-galactosidase activity in cultures with and without 4HB, respectively. In some cases, the measured activities were below a level that is visible in the bar graph. Each value represents the average value of measurements taken from three different culture flasks. Standard deviations were less than 10% of each value. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

CCM was also tested as a carbon source for ADP4003. Despite its apparent inhibitory effect on 4HB catabolism when generated from benzoate, CCM as an exogenous carbon source does not inhibit the degradation of 4HB by the wild-type strain (15). When ADP4003 was grown on CCM, 4HB activated pobA::lacZ transcription during all growth phases (Fig. 3d). The tightly coupled uptake and degradation of CCM may limit the internal cellular concentration of this compound when it is used as a carbon source (15). Thus, regulatory effects due to high internal CCM concentrations during growth on benzoate could be masked during growth on CCM. Regardless of the underlying cause of the regulatory differences, there was a correspondence between growth conditions that allow rapid consumption of 4HB by the wild-type strain and good expression of pobA::lacZ in ADP4003.

Inhibition of pobA expression during growth on substrates of the β-ketoadipate pathway.

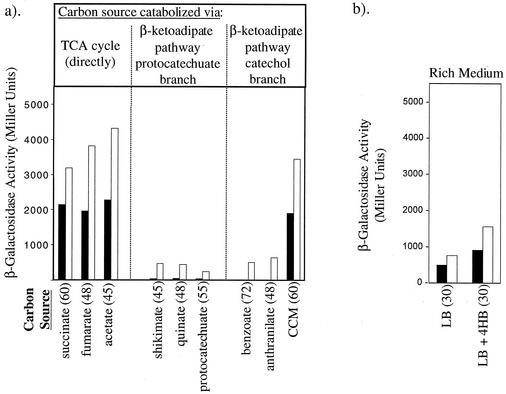

ADP4003 was additionally grown with different substrates in minimal medium (using fumarate, acetate, quinate, protocatechuate, or anthranilate as the sole carbon source) or on rich medium (LB broth). β-Galactosidase activities were measured in these cultures as for the experiments shown in Fig. 3. In each experimental set with a single carbon source, expression of pobA::lacZ was undetected or very low in the absence of 4HB (data not shown). The results for the cultures to which 4HB had been added are summarized in Fig. 4a. Only two β-galactosidase values are shown for each growth condition, one at a time midway through the exponential growth phase (black bars) and the other at the onset of stationary phase (open bars).

FIG. 4.

Expression of a pobA::lacZ chromosomal transcriptional fusion in strain ADP4003. (a) Nine individual carbon sources were used as indicated in minimal medium containing 10 μM 4HB. (b) Cultures were grown in LB broth with or without 10 μM 4HB. The generation time in minutes is indicated parenthetically. Closed bars indicate the level of β-galactosidase activity at a point midway through the exponential growth phase, and open bars indicate this activity at the start of stationary phase. Enzyme activity values represent the averages of nine or more trials for each growth condition. Standard deviations were less than 10% of each value. TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

With fumarate or acetate as the carbon source, expression of pobA was similar to that of succinate-grown cells. These organic acids, which feed directly into the tricarboxylic acid cycle, allowed 4HB to activate pobA expression. However, with quinate or protocatechuate as the carbon source, β-galactosidase activities were negligible during exponential growth and low in the stationary phase (Fig. 4a). This pattern of pobA::lacZ expression was indistinguishable from that obtained with shikimate as the growth substrate (Fig. 3c). This pattern was also similar to that obtained with anthranilate or benzoate as the growth substrate (Fig. 4a). Thus, pobA expression was inhibited during growth on five carbon sources degraded via the protocatechuate or catechol branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway.

During growth on LB medium, there was low-level pobA::lacZ expression without exogenous 4HB (Fig. 4b). Addition of 4HB to LB medium increased the activity levels less than twofold (Fig. 4b). In comparison, 4HB increased pobA::lacZ expression approximately 200-fold when succinate, fumarate, acetate, or CCM was the carbon source in minimal medium.

Identification of regulatory proteins that inhibit the ability of PobR to activate pobA expression.

Multiple regulatory factors are likely to be involved in the control of pobA expression under different growth conditions. To understand certain aspects of genetic control in better detail, our next studies focused specifically on the inhibition of 4HB consumption during growth on benzoate. Since endogenous CCM inhibits 4HB catabolism (15), we tested whether transcriptional regulators that respond to this compound play a role in the inhibition. Although these regulators, BenM and CatM, activate the transcription of genes for benzoate degradation in the presence of CCM, under some conditions, they repress gene expression (4, 6).

To test whether BenM and CatM bind to genetic regions involved in the catabolism of 4HB, purified proteins were used in gel retardation assays in vitro. This method failed to reveal binding of either BenM or CatM to the pobA operator-promoter DNA, the region depicted as box 2 in Fig. 1b (data not shown). Moreover, excess unlabeled pobA DNA did not compete for protein binding in vitro when either BenM or CatM bound to a promoter that they regulate in the ben gene region, the benP promoter (the region depicted as box 3 in Fig. 1c) (5). Thus, when gel retardation methods were used, neither regulator recognized pobA.

Further studies tested whether BenM and CatM bind to other genes involved in 4HB catabolism. After the PobA-catalyzed conversion of 4HB to protocatechuate, subsequent catabolism depends on the pcaIJFBDKCHG genes. These pca genes are activated by PcaU, a PobR-like regulator, that is encoded by the divergently transcribed pcaU gene (Fig. 1 and 2) (16, 29). A sequence immediately downstream of the pcaU transcriptional start site, ATAT-seven nucleotides-GTAT, resembles known CatM and BenM binding sites that are upstream of the transcriptional start sites of genes involved in benzoate catabolism (Fig. 5a).

When the operator-promoter region for the pcaU-pcaI genes (box 1 in Fig. 1b) was used in the gel retardation assay (Fig. 5b to d), it bound to either CatM or BenM. As shown for CatM, the presence of CCM enhanced the binding affinity of this regulator for the pca region (Fig. 5b and c). Similar results were obtained with BenM in the assay (data not shown). Unlabeled pca DNA, but not nonspecific DNA, competed with the labeled probe for protein binding (data not shown). These results demonstrated interactions between CatM and BenM and the pcaU-pcaI regulatory region in vitro. However, the physiological significance of these interactions could not be assessed by the gel retardation assays. To test the requirement for BenM and CatM in the inhibition of 4HB utilization during growth on benzoate, regulatory mutants were characterized.

Benzoate and 4HB catabolism in mutants lacking BenM and CatM.

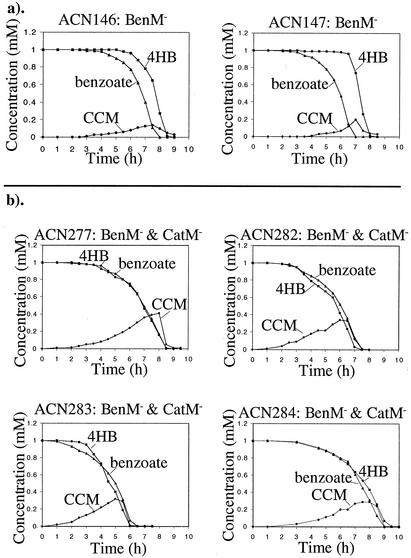

Previous studies showed that disruption of benM in strain ISA36 prevents benzoate from inhibiting 4HB catabolism (6). Since the benM mutation also prevents growth on benzoate and limits the production of the inhibitory metabolite CCM, no conclusions could be drawn concerning a direct role for BenM in the regulation of the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway. Here we examined the consumption of 4HB and benzoate by two strains derived from ISA36. These strains, ACN146 and ACN147, lack BenM but can use benzoate as a sole carbon source because a point mutation in the benA operator-promoter region of each allows BenM-independent expression of the benABCDE operon (4, 6). Thus, both produce CCM endogenously during growth on benzoate. Here, cultures of ACN146 and ACN147 were each provided with equimolar (1 mM) amounts of benzoate and 4HB as growth substrates. The concentrations of metabolites remaining in the culture medium at subsequent time points were quantified by HPLC. Unlike the parent strain, ISA36, from which they were derived, each consumed benzoate prior to 4HB (Fig. 6a). For example, after approximately 7 h, nearly all of the benzoate had been consumed. In contrast, at this time, most of the 4HB remained in the medium and was consumed only when the benzoate had been sufficiently depleted. This is the wild-type order of consumption (15). Therefore, BenM is not essential for inhibition of 4HB consumption during growth on benzoate. Similarly, previous studies showed that CatM is not essential for inhibition of 4HB catabolism when this compound is provided as a growth substrate together with benzoate (15).

FIG. 6.

Concentration of metabolites in the culture medium of BenM mutants (a) or BenM and CatM mutants (b) grown in minimal medium with 1 mM benzoate and 1 mM 4HB. The strains are described more fully in Table 1 and in the text. Catechol (not shown) accumulated transiently during the growth of ACN277, ACN282, ACN283, and ACN284.

Since CatM and BenM have overlapping functions, the absence of both regulators might alleviate the inhibition of 4HB consumption during growth on benzoate. As described in a separate report, strains were isolated that grow on benzoate without CatM or BenM (30). Here, we assessed the abilities of four such benM and catM mutants (ACN277, ACN282, ACN283, and ACN284) to degrade benzoate and 4HB (Fig. 6b). In each case, the mutant strains degraded benzoate and 4HB concurrently. The presence of either CatM or BenM in mutants appears to be sufficient to inhibit 4HB utilization during growth on benzoate. In contrast, the loss of both regulators in four independently isolated mutants alleviated this inhibition.

DISCUSSION

The CatM and BenM transcriptional regulators contribute to cross-regulation of the catechol and protocatechuate branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway.

Individual components in an aromatic compound mixture are consumed by Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 in a sequential order (15). The underlying regulation that determines this order may prevent mismatched interactions from occurring between the similarly structured enzymes and substrates of the two branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway. Despite the importance of this metabolic control, it has been difficult to characterize cross-regulation between the pathway branches. Here, a combination of in vivo and in vitro methods was used to investigate the inhibition of 4HB utilization that occurs in the presence of alternative aromatic carbon sources.

Studies of a chromosomal lacZ reporter indicated that during growth on benzoate, transcriptional-level regulation prevents expression of pobA, the gene encoding the first enzyme needed for 4HB degradation (Fig. 3). Expression of this gene requires the PobR activator (11, 12). While some compounds similar in structure to 4HB act as anti-inducers to prevent PobR-mediated transcriptional activation of pobA, benzoate itself is not an effective anti-inducer (11). Rather, the metabolite CCM plays a role in the inability of 4HB and PobR to activate pobA transcription during growth on benzoate (15). In the presence of CCM, CatM and BenM each bound to the pcaU-pcaI regulatory region (Fig. 5; additional data not shown).

Although BenM and CatM are transcriptional activators for genes involved in benzoate degradation (Fig. 2), they also act as repressors by negatively regulating their own expression (6, 31). Furthermore, in the absence of the metabolites to which they respond, BenM and CatM repress the basal expression of the benABCDE operon (4). The position of the regulator-DNA binding sites relative to the promoter determines whether repression or activation occurs. If CCM causes the regulators to bind to the predicted site in the pca region, protein binding should interfere with pcaU expression. Our studies did not localize binding within the 291-bp pca fragment (Fig. 5). However, a likely target for protein binding was suggested by a sequence that matches BenM and CatM binding sites that have been well characterized by DNA footprinting techniques (4, 31). Binding of CatM or BenM to this pca site may also affect the binding of PcaU to an adjacent site where it activates transcription from the pcaI promoter (29, 38). Consistent with an inhibitory role for CCM, this compound enhanced the binding of BenM or CatM to pca DNA (Fig. 5). Increased concentrations of protein and CCM resulted in increased amounts of the higher of two shifted DNA species (C1 in Fig. 5b).

Connections between pca and pobA gene expression.

Repressed pca transcription may reduce pobA expression during growth on benzoate (Fig. 2). Since PcaU activates transcription of the pcaIJBDKCHG genes, repressed pcaU expression should prevent high-level transcription from the pcaI promoter. Thus, in the presence of CCM, BenM and CatM may inhibit the induction of PcaK, a transport protein involved in the uptake of 4HB (10). Reduced uptake may, in turn, prevent or lower PobR-mediated 4HB-dependent transcriptional activation of pobA. This scenario raises the possibility that ADP1 and P. putida PRS2000, bacteria that differ significantly in genetic organization and regulation, have the same regulatory mechanism for consumption of benzoate prior to 4HB. Each strain may use a transcriptional activator of benzoate catabolism to reduce expression of the pcaK transport gene (7). Although the VanK transporter sometimes compensates for the loss of PcaK in ADP1 (10), it is unknown whether VanK transports 4HB during growth on benzoate. Further studies are needed to test the significance of transport in the inhibition of 4HB consumption.

Another possibility is that regulatory circuits linking the expression of the pobA and pca genes do not depend on pcaK per se. Reduced levels of the transcriptional regulator PcaU could affect gene expression at locations other than the pcaI operator-promoter region. PcaU may be involved in a regulon whose target genes have yet to be fully characterized. Sequence similarities between the PcaU and PobR regulators have led to speculation that these two regulators, like BenM and CatM, have overlapping or interconnected functions (9, 21, 39).

Overlapping functions of CatM and BenM.

CatM and BenM are homologous LysR-type transcriptional regulators with distinct functions. However, both proteins respond to CCM and can recognize the same DNA binding sequences (4). In mutants lacking either CatM or BenM, the remaining regulator sometimes compensates for the loss of the other. For example, both CatM and BenM must be absent to eliminate transcriptional activation of benP and catA (5, 31). As shown previously, benzoate-dependent inhibition of 4HB catabolism occurs in mutant ISA13, which lacks CatM but retains BenM (15). As shown here, similar inhibition occurs in mutants that lack BenM but retain CatM, strains ACN146 and ACN147 (Fig. 6a). The latter strains grow on benzoate because each has a point mutation in the benA operator-promoter region that allows high-level BenM-independent transcription of the benABCDE operon (6). These strains were derived from a benM mutant, ISA36, that does not inhibit 4HB consumption in the presence of benzoate (6). Presumably, the inhibition is prevented because the benM mutation blocks the conversion of benzoate to the inhibitory metabolite CCM. In strains that produce CCM endogenously, the presence of either CatM or BenM was sufficient for the inhibition of 4HB utilization.

To test the effect of the absence of both regulators, mutants were studied that grow on benzoate without CatM or BenM. These mutants (ACN277, ACN282, ACN283, and ACN284) were derived from ACN147, and they compensate for low-level cat gene expression by amplifying a section of the chromosome containing these genes (30). The mutants grow well on benzoate, although the precise segment of amplified DNA varies in each mutant (30). Although these mutants generated CCM endogenously from benzoate, they failed to inhibit 4HB consumption during growth on benzoate (Fig. 6). This failure was attributed to the loss of BenM and CatM. Collectively, the data support the model in which these regulators, in the presence of CCM, repress the expression of genes involved in 4HB catabolism. The binding of BenM and CatM to the pcaU-pcaI region provides the first evidence of direct transcriptional cross-regulation between the catechol and protocatechuate branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway.

Carbon source-dependent gene expression is complex.

Clearly, BenM and CatM are not the sole regulators of aromatic carbon source preferences. CCM is only generated during growth on substrates of the catechol branch of the pathway (Fig. 1). During growth on protocatechuate, the pca genes are expressed at high levels. Thus, the use as carbon sources of protocatechuate or compounds degraded via protocatechuate, such as shikimate and quinate, should not reduce pobA expression by repressing transcription of the pca genes. The observation that pobA expression was turned off during growth on substrates of the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway is surprising, since there are no obvious reasons for such transcriptional regulation. Nevertheless, reduced pobA expression correlated with the rapid depletion of shikimate from a mixture of aromatic substrates while 4HB remained intact (15).

The periplasmic location of the enzymes needed to convert both shikimate and quinate to protocatechuate may necessitate that all of these carbon sources require protocatechuate uptake via the PcaK transporter (10). During growth on preferred substrates of the protocatechuate branch, PcaK might play a role in the cellular exclusion of 4HB, the inducer of pobA expression. In this case, regulation could be mediated by the specificity of the PcaK transporter rather than by pcaK expression. This model remains to be tested experimentally and does not preclude the involvement of other regulatory mechanisms.

The effects of LB medium on pobA expression were difficult to interpret. The relatively high pobA expression in the absence of added 4HB (Fig. 4b) might result from aromatic inducers being in the medium. Furthermore, the metabolism of aromatic components in LB medium might generate inhibitory catabolites that prevent 4HB from fully activating pobA expression. However, the unexpected pattern of gene expression raises the possibility of additional regulation. For example, in pseudomonads, catabolite repression in rich medium is mediated by the Crc global regulator and by cyo genes that affect the redox state of the cell (13, 27, 40).

Recently, Dal et al. addressed carbon catabolite repression in ADP1 (8). Analysis of enzymes and transcripts demonstrated that growth on succinate and acetate represses the expression of pca and pob genes (8). Succinate, acetate, and other organic acids participate in the catabolic repression of aromatic and aliphatic growth substrates in Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, and Ralstonia species (2, 3, 22, 23). During growth of ADP4003 on succinate, fumarate, or acetate, the pobA::lacZ expression levels were relatively high and comparable for all (Fig. 4). However, in our studies, these levels could not be compared to those found during growth on 4HB, the condition expected to yield maximal transcription of pobA. In ADP4003, disruption of pobA by the lacZ reporter prevents 4HB from serving as a growth substrate.

Under all growth conditions, pobA expression increased at the end of the exponential phase. By this time, inhibitory catabolites, such as CCM, should be metabolically depleted. Moreover, the consistent increase in expression raises the possibility that gene expression at some promoter(s) is regulated by an alternative stationary-phase sigma factor, as occurs with carbon source regulation in pseudomonads (13, 37). Many details of 4HB consumption in multisubstrate environments remain unknown. Nevertheless, the characterization of carbon source-dependent expression of pobA provides a framework for understanding and interpreting continued regulatory studies of carbon source preferences in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth R. Wilson and Amy S. Kilgore, who, as undergraduate students, made significant contributions by assaying LacZ enzyme activities and by analyzing the data.

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB-0212604 to E.L.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ampe, F., D. Leonard, and N. D. Lindley. 1998. Repression of phenol catabolism by organic acids in Ralstonia eutropha. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ampe, F., and N. D. Lindley. 1995. Acetate utilization is inhibited by benzoate in Alcaligenes eutrophus: evidence for transcriptional control of the expression of acoE coding for acetyl coenzyme A synthetase. J. Bacteriol. 177:5826-5833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ampe, F., J.-L. Uribelarrea, G. M. F. Aragao, and N. D. Lindley. 1997. Benzoate degradation via the ortho pathway in Alcaligenes eutrophus is perturbed by succinate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2765-2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundy, B. M., L. S. Collier, T. R. Hoover, and E. L. Neidle. 2002. Synergistic transcriptional activation by one regulatory protein in response to two metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7693-7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, T. J., C. Momany, and E. L. Neidle. 2002. The benPK operon, proposed to play a role in transport, is part of a regulon for benzoate catabolism in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Microbiology 148:1213-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier, L. S., G. L. Gaines III, and E. L. Neidle. 1998. Regulation of benzoate degradation in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 by BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional activator. J. Bacteriol. 180:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowles, C. E., N. N. Nichols, and C. S. Harwood. 2000. BenR, a XylS homologue, regulates three different pathways of aromatic acid degradation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 182:6339-6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dal, S., I. Steiner, and U. Gerischer. 2002. Multiple operons connected with catabolism of aromatic compounds in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 are under carbon catabolite repression. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:389-404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Spontaneous mutations affecting transcriptional regulation by protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, W. M. Coco, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J. Bacteriol. 181:3505-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMarco, A. A., B. Averhoff, and L. N. Ornston. 1993. Identification of the transcriptional activator PobR and characterization of its role in the expression of pobA, the structural gene for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 175:4499-4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMarco, A. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. Regulation of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase synthesis by PobR bound to an operator in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 176:4277-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinamarca, M. A., A. Ruiz-Manzano, and F. Rojo. 2002. Inactivation of cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase relieves catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 184:3785-3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ditty, J. L., and C. S. Harwood. 2002. Charged amino acids conserved in the aromatic acid/H+ symporter family of permeases are required for 4-hydroxybenzoate transport by PcaK from Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 184:1444-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaines, G. L., III, L. Smith, and E. L. Neidle. 1996. Novel nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy methods demonstrate preferential carbon source utilization by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 178:6833-6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerischer, U., A. Segura, and L. N. Ornston. 1998. PcaU, a transcriptional activator of genes for protocatechuate utilization in Acinetobacter. J. Bacteriol. 180:1512-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harwood, C. S., N. N. Nichols, M.-K. Kim, J. L. Ditty, and R. E. Parales. 1994. Identification of the pcaRKF gene cluster from Pseudomonas putida: involvement in chemotaxis, biodegradation, and transport of 4-hydroxybenzoate. J. Bacteriol. 176:6479-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Heinaru, E., S. Viggor, E. Vedler, J. Truu, M. Merimaa, and A. Heinaru. 2001. Reversible accumulation of p-hydroxybenzoate and catechol determines the sequential decomposition of phenolic compounds in mixed substrate cultivations in pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:79-89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juni, E., and A. Janik. 1969. Transformation of Acinetobacter calco-aceticus (Bacterium anitratum). J. Bacteriol. 98:281-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kok, R. G., D. A. D'Argenio, and L. N. Ornston. 1998. Mutation analysis of PobR and PcaU, closely related transcriptional activators in Acinetobacter. J. Bacteriol. 180:5058-5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin, M. M., T. H. M. Smits, J. B. Van Beilen, and F. Rojo. 2001. The alkane hydroxylase gene of Burkholderia cepacia RR10 is under catabolite repression control. J. Bacteriol. 183:4202-4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFall, S. M., B. Abraham, C. G. Narsolis, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1997. A tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediate regulating transcription of a chloroaromatic biodegradative pathway: fumarate-mediated repression of the clcABD operon. J. Bacteriol. 179:6729-6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Nichols, N. N., and C. S. Harwood. 1995. Repression of 4-hydroxybenzoate transport and degradation by benzoate: a new layer of regulatory control in the Pseudomonas putida β-ketoadipate pathway. J. Bacteriol. 177:7033-7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsek, M. R., W. M. Coco, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1994. Gel-shift assay and DNase I footprinting analysis of transcriptional regulation of biodegradation genes. Methods Mol. Genet. 3:273-290. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petruschka, L., G. Burchhardt, C. Muiller, C. Weihe, and H. Herrmann. 2001. The cyo operon of Pseudomonas putida is involved in carbon catabolite repression of phenol degradation. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pieper, D. H., and W. Reineke. 2000. Engineering bacteria for bioremediation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:262-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popp, R., T. Kohl, P. Patz, G. Trautwein, and U. Gerischer. 2002. Differential DNA binding of transcriptional regulator PcaU from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 184:1988-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reams, A. B., and. E. L. Neidle. 2003.. Genome plasticity in Acinetobacter: new degradative capabilities acquired by the spontaneous amplification of large chromosomal segments. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1291-1304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Romero-Arroyo, C. E., M. A. Schell, G. L. Gaines III, and E. L. Neidle. 1995. catM encodes a LysR-type transcriptional activator regulating catechol degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 177:5891-5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saier, M. H. 1998. Multiple mechanisms controlling carbon metabolism in bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 58:170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Shanley, M. S., E. L. Neidle, R. E. Parales, and L. N. Ornston. 1986. Cloning and expression of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus catBCDE genes in Pseudomonas putida and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 165:557-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stulke, J., and W. Hillen. 2000. Regulation of carbon catabolism in Bacillus species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:849-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobiason, D. M., A. G. Lenich, and A. C. Glasgow. 1999. Multiple DNA binding activities of the novel site-specific recombinase, Piv, from Moraxella lacunata. J. Biol. Chem. 274:9698-9706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tover, A., E. L. Ojangu, and M. Kivisaar. 2001. Growth medium composition-determined regulatory mechanisms are superimposed on CatR-mediated transcription from the pheBA and catBCA promoters in Pseudomonas putida. Microbiology 147:2149-2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trautwein, G., and U. Gerischer. 2001. Effects exerted by transcriptional regulator PcaU from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 183:873-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young, D. M., D. Parke, D. A. D'Argenio, M. A. Smith, and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Evolution of a catabolic pathway. ASM News 67:362-369. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuste, L., and F. Rojo. 2001. Role of the crc gene in catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 183:6197-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]