Abstract

Previously, we demonstrated that loss of SEMA3F, a secreted semaphorin encoded in 3p21.3, is associated with higher stages in lung cancer and primary tumor cells studied with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and SEMA3F antibodies. In vitro, SEMA3F inhibits cell spreading; this activity is opposed by VEGF. These results suggest that VEGF and SEMA3F compete for binding to their common neuropilin receptor. In the present report, we investigated the attractive/repulsive effects of SEMA3F on cell migration when cells were grown in a three-dimensional system and exposed to a SEMA3F gradient. In addition, we adapted the neurobiologic stripe assay to analyze the migration of tumor cells in response to SEMA3F. In the motile breast cancer cell line C100, which expresses both neuropilin-1 (NRP1) and neuropilin-2 (NRP2) receptors, SEMA3F had a repulsive effect, which was blocked by anti-NRP2 antibody. In less motile MCF7 cells, which express only NRP1, SEMA3F inhibited cell contacts with loss of membrane-associated E-cadherin and β-catenin without motility induction. Cell spreading and proliferation were reduced. These results support the concept that in a first step during tumorigenesis, normal tissues expressing SEMA3F would try to prevent tumor cells from spreading and attaching to the stroma for further implantation.

Keywords: Semaphorin SEMA3F, migration, stripe assay, cocultures, E-cadherin

Introduction

Class 3 semaphorins, including SEMA3F [1], are a family of secreted molecules initially identified on the basis that they cause collapse of nerve growth cones [2]. However, these semaphorins are widely expressed outside the central nervous system, consistent with additional functions. Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) and neuropilin-2 (NRP2) were identified as high-affinity semaphorin receptors [3,4]. More recently, these receptors have been shown to associate with and require Plexin A for signaling [5]. In addition, the adhesion molecule L1-CAM [6,7] and integrins [8] could be part of the complex. Interestingly, the neuropilins were independently identified as coreceptors in endothelial cells for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)165 [9]. The prototype class 3 semaphorin, Sema3A (collapsin), was shown to block VEGF-induced motility and lamellipodia formation [10]. Similarly, we demonstrated that SEMA3F and VEGF had reciprocal immunostaining patterns in primary lung cancer cells [11] and, in breast cancer cell lines SEMA3F and VEGF, had opposing NRP-dependent effects on cell attachment and spreading [12]. Together, these results suggest that class 3 semaphorins either compete with VEGF for NRP binding, or bind distinctly with opposing actions.

Both SEMA3F and SEMA3B map to 3p21.3, a region of frequent loss in lung and breast cancers [13–15]. In primary lung tumor cells, antibody staining for SEMA3F correlates with both tumor stage and histologic subtypes [11], and loss of SEMA3F is an early event in lung cancer development [16]. SEMA3F expression inhibits mouse fibrosarcoma A9 cell tumorigenicity [17] as well as HEK 293-induced tumors [18]. Similarly, transfection of SEMA3B inhibited in vitro colony formation by NCI-H1299 lung cancer cells [19] and tumorigenesis of HEY ovarian adenocarcinoma cells [20]. Thus, SEMA3F and SEMA3B demonstrate clear antitumor activity.

During normal axon development, semaphorins exert directional effects due to concentration gradients [21]. In the present report, which is an extension of our previous work, we have studied the effects of SEMA3F on tumor cell migration using both three-dimensional cocultures with a unidirectional SEMA3F gradient, as well as the stripe assay in which cells can migrate to either SEMA3F-positive or SEMA3F-negative segments. These studies demonstrate that SEMA3F had a repulsive effect on C100 cells, which express NRP1 and NRP2, and that this effect was mediated by NRP2. On less motile MCF7 cells, which only express NRP1, exposure to SEMA3F led to disrupted intercellular contacts with delocalization of E-cadherin and β-catenin. This effect was mediated by NRP1. Moreover, MCF7 cells exposed to SEMA3F were less proliferative, although they did not undergo apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructions and Cell Lines

SEMA3F cDNA was cloned into pSecTagA vector at the 3′ end of the alkaline phosphatase gene (AP-SEMA3F) and was generously provided by Dr. M. Tessier-Lavigne [4]. APpSecTag (AP) expressed alkaline phosphatase as negative control. Stably transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK 293 and ATTCC CRL 1573) expressing functional recombinant Sema3A or Sema3C (pBKFlagSema3AP1b and pBKFlagSema3CP1b) [22–24] or mock-transfected (control) cells were cultured in MEM plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1 mg/ml G418 (InVitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France). MCF7 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS (InVitrogen). C100 cells, derivatives of MDA-MB-435S [25], were grown in 50% DMEM/50% Ham's F12 containing 10% FCS. COS7 cells were grown in DMEM plus 10% FCS. Transfections of AP or AP-SEMA3F constructs were performed using Effecten (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) with conditions recommended by the manufacturer. For transfected COS7 cells, the medium was replaced 2 days after transfection by DMEM, containing 0.5% FCS or OPTIMEM media (InVitrogen). The medium was collected 4 days after transfection and applied to MCF7 and C100 cell cultures. SEMA3F concentration was estimated by alkaline phosphatase activity (GenHunter, Nashville, TN).

Coculture Assay

Semaphorin-expressing HEK 293 aggregates and tumor cell aggregates were prepared as described previously [26]. Aggregates were placed in 20 µl of chicken plasma on glass coverslips. During plasma coagulation with 20 µl of thrombin, tumor cells aggregates were arranged around semaphorin-secreting HEK 293 aggregates at 100- to 900-µm distances (Figure 1A). After 30 to 45 minutes, the coverslips were placed in Petri dishes with culture media and transferred to an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Blocking experiments were performed by incubating aggregates with 1.0 µg/ml anti-NRP2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or 1.0 µg/ml anti-NRP1 polyclonal antibody (Oncogene, Darmstadt, Germany). After a 72-hour culture, aggregates were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and analyzed. In order to quantify the semaphorin effects, we assigned an index factor varying between -2 and +2 for each aggregate based on the number of tumor cells that migrated from the aggregates. A positive or negative value was attributed to aggregates when cancer cells migrated toward or away from the semaphorin-secreting HEK 293 aggregate, respectively. A null index was attributed to aggregates when no cells escaped from the aggregates, or when cells escaped symmetrically (nondirectionally). Statistical significance between the different mean values was examined using the chi-square test.

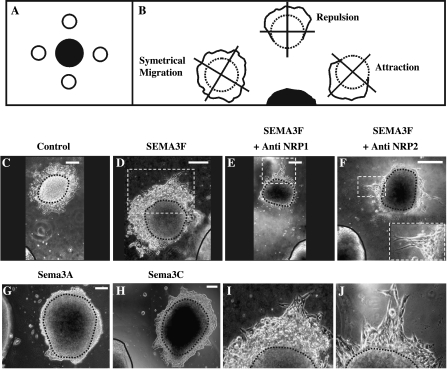

Figure 1.

SEMA3F had a repulsive effect on C100 cells that involved NRP2 receptor. Tumor cell aggregates (A and B, white circle) were arranged all around control or semaphorin-secreting HEK 293 aggregates (A, black circle; B, black semicircle) in a three-dimensional plasma clot. Three major tumor cell migration types could be observed after a 3-day incubation: a symmetrical migration (B, left drawing), a repulsion (B, top central drawing), or an attraction (B, right drawing). C100 cell aggregates were placed in front of HEK 293 aggregates transfected with AP construct (C, control), AP-SEMA3F (D–F), Sema3A (G), or Sema3C (H). In some cases, C100 cells were treated during 3 days with anti-NRP1 (E) or anti-NRP2 (F) antibodies. (I) and (J) are a higher magnifications of the dashed squares represented in (D) and (E), respectively, showing C100 cells escaping from the more distal parts of the aggregates from the SEMA3F source. C100 aggregates are represented by a black dashed line (B–J) and are surrounded by C100 migrating cells. Secreting HEK 293 aggregates are delimited by a black drawing (C–H). In (F), an inset of escaping cells is shown at the bottom right. C100 aggregates are entirely represented, but only a part delimited by the black drawing is shown for secreting HEK 293 aggregates (C–H). Scale bar = 200 µm.

Membrane Preparations and Stripe Assay

Membranes were prepared from ∼ 1 x 106 HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with AP, AP-SEMA3F, or cells stably expressing Sema3A or Sema3C, as described [23,27,28]. Briefly, cells were washed in PBS and placed in homogenization buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM spermidin, 25 µg/ml aprotinin, 25 µg/ml leupeptin (all from COGER, Paris, France) and 15 µg/ml 2,3-dehydro-2-desoxy-N-acetylneuraminic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France)]. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 25,000g in a sucrose gradient (upper phase, 150 µl of 5% sucrose; lower phase, 500 µl of 50% sucrose in PBS). The interband containing the membrane fraction was collected and washed twice in PBS (without Ca2+ and Mg2+) by spinning in a microfuge for 15 minutes at 13,000g. After resuspension in PBS, the concentration of purified membranes was determined by measuring the OD220 nm of solutions diluted 15-fold in 2% SDS. Membrane preparations were supplemented with 3-µl fluorescent beads (Covaspheres; Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, CA) per 100 µl of membrane solution. One drop of membrane suspension was pipetted onto a capillary pore filter connected to a vacuum pump covered by a silicone matrix. Membranes were transferred onto the nylon matrix to form stripes. These stripes (on capillary pore filters) were transferred to poly-l-lysine-coated (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) glass coverslips. The glass coverslips were then transferred to Petri dishes containing culture media. Finally, C100 and MCF7 cells were added to the Petri dishes at a density of 2 x 105 cells/ml, cultured for 24 hours, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Blocking antibodies (described above) were added for a period of 24 hours prior to fixing. Analysis of stripe assays was performed using the Metaview 5.0 universal imaging system to drive the motorized plate of an inverted microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Cells on stripes and in the interstripe space were counted and their mean values were analyzed statistically using the chi-square test.

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes and then permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes at room temperature. A first antibody was applied during 1 hour: E-cadherin mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100) raised against amino acids 735 to 863 (BD Biosciences, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) or β-catenin mouse monoclonal antibody HRPO-linked (1:100) raised against amino acids 571 to 781 (BD Biosciences). A goat antimouse antibody bound to CY3 (1:200; Interchim, Montluçon, France) was used as a second antibody. Immunostained samples were finally examined using the yellow line (568 nm) of the confocal microscope (BioRad, Hemel Hempstead, UK) as described previously [12].

Western Blots

A total of 2.5 x 106 MCF7 and C100 cells were washed twice with cold PBS, then lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40 (wt/vol), 1% DOC (wt/vol), 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1.25 mM PMSF, 20 µM leupeptin, 0.8 µM aprotinin, and 10 mM pepstatin]. The amount of protein in each lysate was measured using the BCA kit protocol (PerBio Sciences, Bezons, France). Fifty micrograms of protein per well was resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. Equal loading was verified by Coomassie staining of separately run gels and by Western blotting with an anti-α-tubulin antibody. The antibodies and dilutions were: anti-α-tubulin (mouse monoclonal, 1:1000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich), E-cadherin (described above, 1:2500), β-catenin (mouse monoclonal raised against amino acids 571 to 781, HRPO-linked, 1:1000; BD Biosciences), N-cadherin (mouse monoclonal antibody raised against a portion of the chick intracellular domain, 1:5000; Clinisciences, Montrouge, France), and sheep antimouse IgG (HRP-linked, 1:2000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnologies, Buckinghamshire, UK). Detection was performed by ECL.

Apoptosis Assay

A total of 2 x 105 cells were cultured for 2 days before an additional 24-hour stimulation with 100 ng/ml AP-SEMA3F in conditioned medium, or with an equivalent volume of control AP medium. Apoptotic cells were visualized using the TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) of DNA fragments (apoptosis detection system, Fluorescein; Promega, Madison, WI). A positive apoptotic control was made by treating cells for 16 hours with 1.5 µM staurosporin. Fluorescein labelling was examined using the blue line (488 nm) of the confocal microscope. Nuclei were also stained after fixation using 50 µg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining was observed using the yellow line (568 nm) of the confocal microscope. Nonapoptotic (PI-positive) and apoptotic (PI- and fluorescein-positive cells) cells were counted and statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test.

Cell Proliferation Test

A total of 1 x 105 cells were treated with either 100 ng/ml AP-SEMA3F in conditioned medium or with control AP medium, and were cultured for 24 hours in the incubation chamber of a motorized microscope (Zeiss). Microcinematography was performed using the Metaview 5.0 universal imaging system. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the Rneasy Mini kit (Qiagen). RT-PCR was performed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (InVitrogen) using the procedure supplied by the manufacturer. We assessed levels of E-cadherin mRNA normalized to GAPDH by quantitative real-time PCR carried out with the ABI 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) system using SYBR-Green chemistry. The cycle at which a particular sample reaches an arbitrary threshold fluorescent level (Ct) is indicative of the amount of input template. The following E-cadherin primers were used: Ecadh For (5′ CGG GAA TGC AGT TGA GGA TC 3′), Ecadh Rev (5′-AGG ATG GTG TAA GCG ATG GC-3′). GAPDH cDNA was amplified with primers GAPDH For (5′-TGC-ACC-ACC-AAC-TGC-TTA-GC-3′) and GAPDH Rev (5′-GGC-ATG-GAC-TGT-GGT-CAT-GAG-3′). The PCR was carried out in 20-µl reaction volumes consisting of 1 x PCR SYBR Green buffer, 0.125 µM of primers, 200 µM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.025 U/µl AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems). cDNA was amplified as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute.

Results

SEMA3F Exhibits Repulsive Activities Toward C100 Migration

C100 cells are highly motile and grow in a dispersed fashion [12]. These cells express both NRP1 and NRP2, but only low levels of SEMA3F are measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR [12]. To determine whether SEMA3F affected C100 migration, we applied the three-dimensional coculture guidance assay in which tumor cell aggregates and HEK 293 aggregates secreting either alkaline phosphatase-tagged SEMA3F (AP-SEMA3F) or alkaline phosphatase alone (AP control) were incubated in close proximity (Figure 1A). After a 3-day incubation, each aggregate was observed and virtually subdivided in quadrants (Figure 1B). When tumor cells migrated homogenously in all quadrants (Figure 1B, left condition) or when there was no migration in all quadrants, we considered that there was no migratory effect of HEK 293 aggregates and an arbitrary null index factor was attributed. On the contrary, when cells migrated in the two most distal quadrants (Figure 1B, top central condition) or the two most proximal quadrants from HEK 293 aggregates (Figure 1B, right condition), we considered that there was a repulsion or an attraction, respectively, and we attributed to these aggregates a negative or a positive index factor.

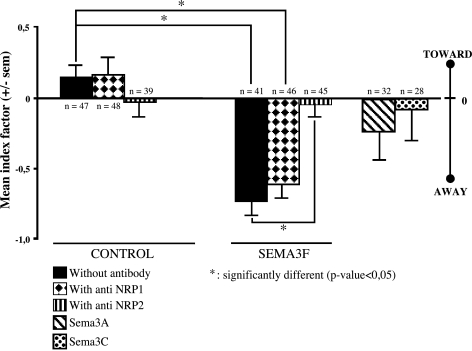

After 3 days, C100 cells migrated all around the tumor aggregate in an apparent random or diffuse manner with the AP control HEK 293 aggregates (Figures 1C and 2). In contrast, the C100 cells did not migrate in the direction of the AP-SEMA3F-expressing HEK 293 aggregates but only escaped from the most distant part of the tumor aggregate (Figures 1, D and I and 2). This effect was strongly inhibited by anti-NRP2 antibodies (Figures 1F and 2), whereas no differences were observed with anti-NRP1 antibodies (Figures 1, E and J and 2). In addition, C100 migration was not affected by HEK 293 aggregates expressing Sema3A or Sema3C (Figures 1, G and H and 2).

Figure 2.

Quantification of the repulsive effect of SEMA3F on C100 cell migration. A positive or a negative index varying between +2 and -2 was attributed to each C100 aggregate when tumor cells migrate toward or away from the source of semaphorin, respectively (see Materials and Methods section and Figure 1). A mean index factor was calculated for each condition and was represented as a bar graph. n = number of analyzed aggregates.

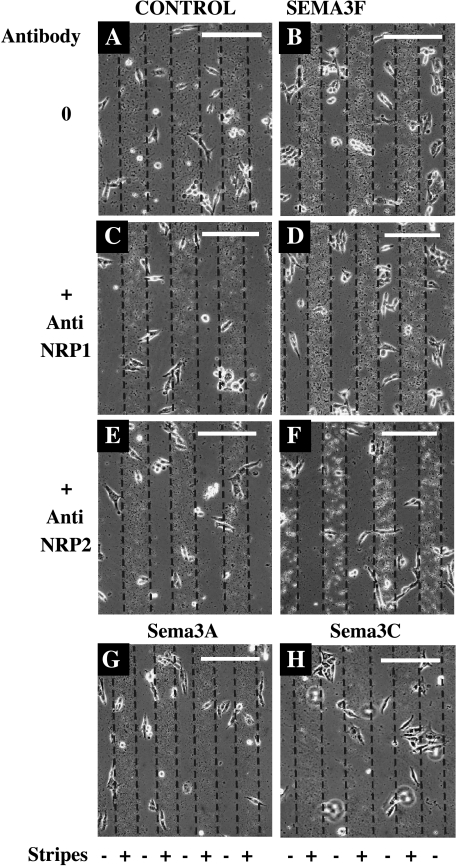

To confirm these results using a complementary approach, we implemented a stripe assay developed by Walter et al. [29]. SEMA3F was immobilized on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips in alternating stripes consisting of membranes derived from AP-SEMA3F-transfected HEK 293 cells. The interstripe spaces contained only the culture medium. Secreted SEMA3F is able to interact with membranous lipids by haptotactism through its positively charged C-terminus [23]. Control stripes were derived from membranes of HEK 293 cells transfected with the control vector (AP). The coverslips were overlaid with C100 cells, then after a 24-hour incubation, cells were fixed and counted.

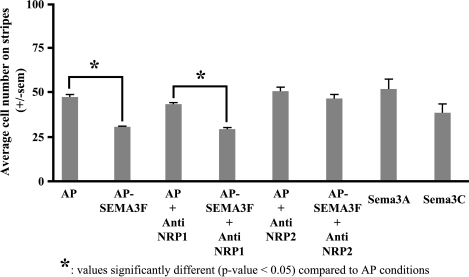

By time lapse microscopy, we observed that C100 cells initially attached equally on stripes and interstripes. Subsequently, however, C100 cells preferentially migrated to the interstripe region when the stripes were derived from AP-SEMA3F-transfected HEK 293 cells (Figures 3B and 4). Most of the cells aligned at the stripe borders but did not penetrate into the stripes. As noted above with the three-dimensional culture system, this effect was not modified by an anti-NRP1 antibody (Figures 3D and 4), but was completely inhibited by an anti-NRP2 antibody (Figures 3F and 4). Similarly, stripes derived from Sema3A- and Sema3C-transfected HEK 293 cells had no significant effect on C100 migration (Figures 3, G and H and 4). Thus, we conclude that SEMA3F has a specific repulsive activity on the migration of C100 cells, which is mediated by NRP2.

Figure 3.

C100 cells escaped from SEMA3F in a stripe assay. Membranes from HEK 293 cells transfected with AP (A, C, and E, control), AP-SEMA3F constructs (B, D, and F), Sema3A (G), or Sema3C (H) were used to make stripes on glass coverslips. Cells were spread and cultured for 24 additional hours with anti-NRP1 (C and D) or anti-NRP2 (E and F) antibodies. Presence or absence of semaphorin is indicated by (+) or (-), respectively. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Quantification of C100 cells escaping from SEMA3F. The mean number of C100 cells on stripes (where there is a source of SEMA3F) was calculated from stripe experiments as described in Figure 3 and represented as a histogram with or without anti-NRP1 and anti-NRP2 antibodies. Three independent experiments were performed.

SEMA3F Actions on MCF7 Cells

MCF7 cells grow in tight clusters, are much less motile than C100, and express NRP1 but not NRP2 [12]. In the three-dimensional coculture assay, no differences in MCF7 migration were seen when these cells were placed in proximity to either the control or SEMA3F-expressing HEK 293 aggregates (data not shown). We were surprised by this result because we previously observed that exposure to SEMA3F resulted in loss of lamellipodia and cell attachment, which was mediated by NRP1 [12]. Importantly, it shows that SEMA3F is not able to promote the motility of MCF7 cells, on the contrary to HGF/SF, which enhances the invasive potential and scattering of these cells [30]. In the three-dimensional coculture assay, Sema3A and Sema3C had a tendency to attract MCF7 cells (data not shown). In the SEMA3F stripe assay, MCF7 cells were equally distributed between the stripe and interstripe regions (data not shown). Likewise, no differences were noted when the stripes were derived from Sema3A- or Sema3C-expressing cells. It is possible that the lack of demonstrable migration inhibition by SEMA3F is due to the absence of NRP2 or because MCF7 cells are poorly motile. We have not further investigated this issue, although we did confirm that SEMA3F negatively affects the growth of MCF7 cells.

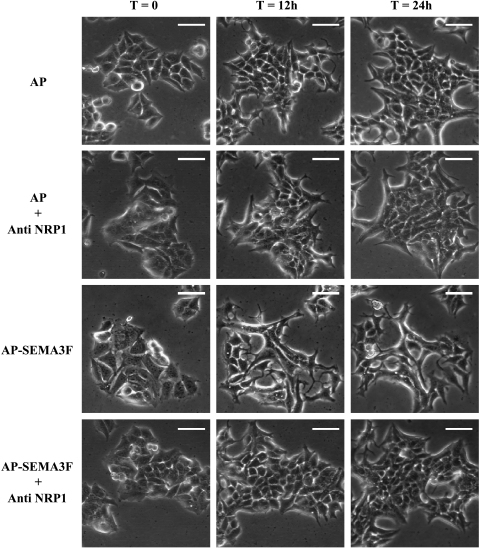

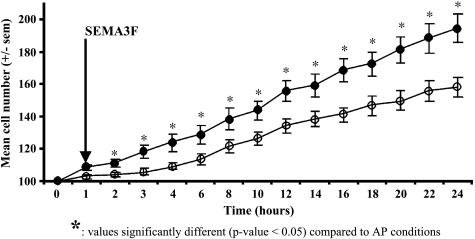

MCF7 cells in islets were observed by time lapse video-microscopy during a 24-hour period under exogenous SEMA3F treatment. We found that SEMA3F-treated islets extended less than control islets (Figure 5) and that fewer cells were present in SEMA3F-treated islets compared to control (doubling time 42.2 vs 25.5 hours for control cells) (Figure 6). Despite their abnormal shape, these cells did not undergo apoptosis using a TUNEL assay (data not shown).

Figure 5.

MCF7 cells retracted and lost cell contacts on SEMA3F treatment. Islets of control (AP) or SEMA3F-treated (AP-SEMA3F) MCF7 cells in the absence or presence of anti-NRP1 antibody were observed by contrast phase microscopy and microcinematography at time 0, 12, and 24 hours. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 6.

Proliferation of MCF7 was reduced on SEMA3F treatment. MCF7 control or SEMA3F-treated cells were counted over a period of 24 hours by microcinematography on selected islets. SEMA3F treatment was performed at time 1 hour. Dark dots, control cells; white dots, SEMA3F-treated cells.

SEMA3F Inhibits E-Cadherin-Mediated Adhesion

MCF7 cells grow in islets and exhibit numerous intercellular contacts. However, when exposed to exogenous SEMA3F, loss of cell-cell contacts was evident by 12 hours and persisted through 24 hours of observation. The cells retracted, became smaller, and detached from each other (Figure 5, third row). These observations are very similar to the disruption of epithelial tumor cell-cell adhesion caused by HGF/SF [31]. However, on SEMA3F treatment, no scattering was observed after cell detachment. No loss of cell-cell contacts was observed in the control-treated cells. The SEMA3F effects were inhibited by an anti-NRP1 antibody (Figure 5, fourth row).

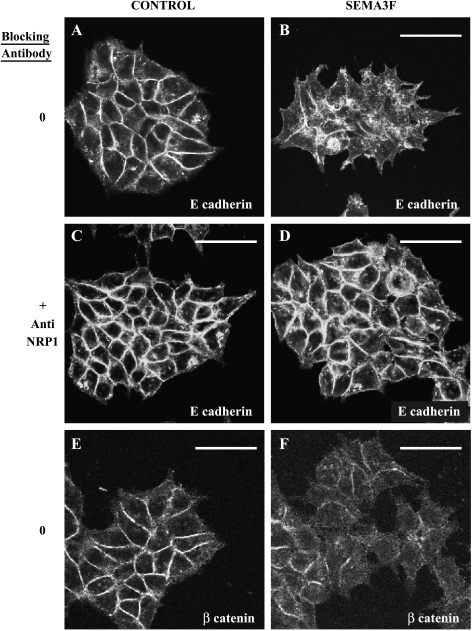

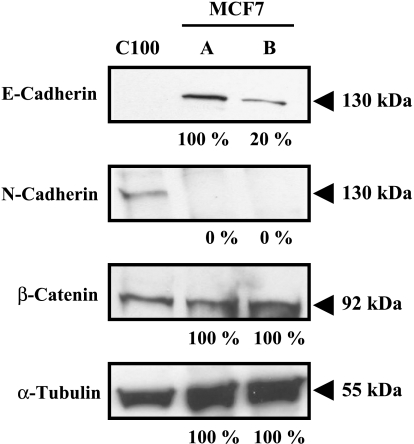

Because of these results, we looked for changes in selected proteins known to affect intercellular adhesion, with E-cadherin being an obvious candidate in epithelial-derived cells. In control MCF7 cells, E-cadherin membrane staining was observed at cell junctions (Figure 7A). On treatment with exogenous SEMA3F, loss in E-cadherin staining was evident after 2 hours (data not shown). After 24 hours, membranous E-cadherin staining was nearly completely lost, although a granular cytoplasmic staining was observed (Figure 7B). This effect was inhibited by an anti-NRP1 antibody (Figure 7, C and D). By Western blot, approximately 80% of the E-cadherin signal was lost after 24 hours (Figure 8), although no changes in E-cadherin mRNA were detected by quantitative RT-PCR (data not shown). By immunofluorescence, β-catenin staining was also reduced (Figure 7, E and F) by SEMA3F, although no loss was detected by Western blot (Figure 8). During tumor progression, loss of E-cadherin has been associated with increased expression of N-cadherin [32], so-called “cadherin switching” [33–35]. However, N-cadherin, which was not expressed in control MCF-7 cells, was not induced following exposure to SEMA3F (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

SEMA3F-treated MCF7 lost membranous E-cadherin and this effect was mediated by NRP1. Observations of control (A and C) or SEMA3F-treated (B and D) MCF7 cells stained by immunofluorescence with an anti-E-cadherin antibody. Incubation with an anti-NRP1 antibody was performed during 1.5 hours (C and D). β-Catenin staining was performed for control (E) or SEMA3F-treated cells (F). Cultures were treated for 24 hours with control AP or AP-SEMA3F media. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 8.

E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and β-catenin expression in SEMA3F-treated MCF7 cells was estimated by Western blot analysis. α-Tubulin staining shows equal protein loading of MCF7 samples. Control MCF7 cells do not express N-cadherin and C100 cells were chosen as a positive control. Quantification is shown under each blot and normalized to 100% for control MCF7 (lane A). Lane B: SEMA3F-treated MCF7 cells.

Discussion

We previously reported that SEMA3F was able to inhibit the attachment and spreading of breast cancer cell lines as evidenced by loss of lamellipodia extensions when cells were grown in a SEMA3F-positive medium [12]. Because semaphorins affect directional migration during neural development, as neurobiologists, we applied similar methods to the analysis of tumor cell directional migration in a SEMA3F-positive environment. We developed the three-dimensional coculture assay where tumor cells faced a SEMA3F gradient. Coculture assays are widely used to detect repellent activities of semaphorins/collapsins in the nervous system [2,23,26], and to study other activities such as cardiac morphogenesis [36]. This approach was completed by stripe assays [23,24,37,38], where cells have the choice to migrate inside or outside a SEMA3F-containing stripe. This assay has been used by neurobiologists to study nerve growth cone guidance, but, to our knowledge, has never been applied by other groups to study migration of cancer cells. Although we used stripes composed of membranes from SEMA3F-transfected HEK 293 cells, stripes can obviously be derived from any cellular source; hence, they are useful for the study of tumor-normal attachment/invasion. We believe that these assays reflect more the in vivo situation where cancer cells develop and escape from tissues presenting a nonhomogenous SEMA3F concentration.

Highly motile C100 cells responded to a gradient of SEMA3F in the coculture assay by not escaping from the aggregates toward the SEMA3F source. This result indicates that either SEMA3F inhibits motility, or has a repulsive activity on cell motility. The results of the stripe assay were most consistent with repulsion because, first, the cells attached equally to the stripe and interstripe regions (data not shown) and then migrated to the interstripes. Antibodies against NRP2 blocked these effects, which is consistent with the demonstrated role of NRP2 in SEMA3F signaling. However, MCF7 cells did not respond to SEMA3F by these two tests. This may be due to the fact that these cells already express SEMA3F [12], are not motile, exhibit numerous intercellular contacts, and express barely detectable levels of NRP2 [12]. However, exposure of these cells to exogenous SEMA3F reduced their ability to expand, which was dependent on NRP1 [12].

In addition to these results, we found in MCF7 cells that intercellular contacts were disrupted by SEMA3F and that this was associated with loss of membranous E-cadherin and its delocalization to the cytoplasm. Initial events in the metastatic spreading of tumors involve loss of cell-cell adhesion within the primary tumor mass. Loss of membranous E-cadherin was NRP1-dependent. Although NRP2 was reported to be the only functional receptor for SEMA3F in the nervous system [39], SEMA3F also binds NRP1 albeit at 10-fold less affinity than NRP2 [4]. This low affinity for NRP1 could explain why MCF7, already expressing SEMA3F, is sensitive to extra SEMA3F. As to the mechanism of E-cadherin loss, we can only speculate at present. Endocytosis of E-cadherin has been observed during mitosis, after HGF-induced cell scattering, and after depletion of extracellular calcium [40–42]. Similarly, Sema3A has been shown to induce endocytosis at sites of membrane retraction [43] and this effect is mediated by L1-CAM association to NRP1-Plexin A1 complex [44]. Thus, SEMA3F could conceivably affect endocytosis. Perhaps a more likely mechanism involves changes in activated surface integrins as semaphorins from class 3 have recently been shown to downregulate activated surface integrins [8]. Interestingly, activation of the repulsive receptor Roundabout inhibits N-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion [45]. Roundabout is the receptor for Slit, another secreted guidance cue, and it was shown that Slit2 is frequently inactivated in colorectal cancer and suppresses the growth of colorectal carcinoma cells [46]. Therefore, cadherin adhesion appears to be inhibited by two guidance molecules, SEMA3F and Slit2. On a cautionary note, we have not yet studied the effects of SEMA3F on E-cadherin on surfaces other than tissue culture plastic-ware and we do not know how these in vitro changes might reflect in vivo effects.

However, loss of E-cadherin is not sufficient by itself to induce metastasis and it has to be associated with increase in N-cadherin level in breast cancer cells. In fact, N-cadherin promotes motility regardless of E-cadherin expression [32]. N-cadherin stimulation did not occur in MCF7 on SEMA3F treatment. In addition, the loss of MCF7 cell-cell contacts is clearly not associated with increased cell motility and proliferation. Thus, loss of E-cadherin would not favor tumor metastasis in our system.

We also examined β-catenin localization in SEMA3F-treated MCF7 cells because cadherin cytoplasmic domains provide F-actin cytoskeleton attachment points through the association of catenins and other cytoskeletal associated proteins. In addition, β-catenin has been shown to function as a downstream transcriptional activator of the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway during morphogenesis and tumorigenesis [47]. Accompanying E-cadherin loss following SEMA3F treatment, we noticed apparent delocalization of β-catenin from the membrane, although the total protein levels did not change as determined by Western blot. This observation is not surprising as a net loss of F-actin has been described at the leading edge of the growth cones when exposed to collapsing factor [48]. In addition, the Wnt/Wingless pathway could be affected as glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3) is activated by Sema3A at the leading edge of growth cones [49].

In summary, SEMA3F has a repulsive effect on motile C100 cells, which is mediated by NRP2. On low motile MCF7 cells, SEMA3F induces loss of cellular contacts with partial delocalization of E-cadherin and β-catenin, but does not promote cell scattering. These changes were associated with a decrease in cell proliferation. In cells that express NRP1 but not NRP2, NRP1 is a functional receptor for SEMA3F. We hypothesize that secreted semaphorins might function in the maintenance of boundaries. In cancer, loss of this function has been shown to enhance cell migration and it appears that opposing autocrine loops involving VEGF and semaphorins can regulate chemotactic activity [50]. These results support the concept that, in a first step during tumorigenesis, normal tissues expressing SEMA3F would try to prevent tumor cells from spreading and attaching to the stroma cells for further implantation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer and Association de Recherche Contre le Cancer (ARC; P.N., S.K., and J.R.), CNRS (B.C.) and FRM (D.B.).

References

- 1.Semaphorin Nomenclature Committee, author. Unified nomenclature for the semaphorins/collapsins. Cell. 1999;97:551–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo Y, Raible D, Raper A. Collapsin: a protein in brain that induces the collapse and paralysis of neuronal growth cones. Cell. 1993;75:217–227. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80064-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolodkin A, Levengood D, Rowe E, Tai Y, Giger R, Ginty D. Neuropilin is a semaphorin III receptor. Cell. 1997;90:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Chédotal A, He Z, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III. Neuron. 1997;19:547–559. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamagnone L, Artigiani S, Chen H, He Z, Ming GI, Song H, Chedotal A, Winberg ML, Goodman CS, Poo M, et al. Plexins are a large family of receptors for transmembrane, secreted, and GPI-anchored semaphorins in vertebrates. Cell. 1999;99:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellani V, DeAngelis E, Kenwrick S, Rougon G. Cis and trans interactions of L1 with neuropilin-1 control axonal responses to semaphorin 3A. EMBO J. 2002;21:6348–6357. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellani V, Rougon G. Control of semaphorin signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:532–541. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serini G, Valdembri D, Zanivan S, Morterra G, Burkhardt C, Caccavari F, Zammataro F, Primo L, Tamagnone L, Logan M, et al. Class 3 semaphorins control vascular morphogenesis by inhibiting integrin function. Nature. 2003;424:391–397. doi: 10.1038/nature01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soker S, Takashima S, Miao H, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell. 1998;92:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miao HQ, Soker S, Feiner L, Alonso JL, Raper JA, Klagsbrun M. Neuropilin-1 mediates collapsin-1/semaphorin III inhibition of endothelial cell motility: functional competition of collapsin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor-165. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:233–242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brambilla E, Constantin B, Drabkin H, Roche J. Semaphorin SEMA3F localization in malignant human lung and cell lines: a suggested role in cell adhesion and cell migration. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:939–950. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64962-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasarre P, Constantin B, Rouhaud L, Harnois T, Raymond G, Drabkin N, Bourmeyster N, Roche J. Semaphorin SEMA3F and VEGF have opposing effects on cell attachment and spreading. Neoplasia. 2003;5:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekido Y, Bader S, Latif F, Chen JY, Duh FM, Wei MH, Albanes JP, Lee CC, Lerman MI, Minna JD. Human semaphorins A (V) and (IV) reside in the 3p21.3 small cell lung cancer deletion region and demonstrate distinct expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4120–4125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang R, Hensel C, Garcia D, Carlson H, Kok K, Daly M, Kerbacher K, Van Den Berg A, Veldhuis P, Buys C, et al. Isolation of the human semaphorin III/F gene (SEMA3F) at chromosome 3p21, a region deleted in lung cancer. Genomics. 1996;32:39–48. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roche J, Boldog F, Robinson M, Robinson L, Varella-Garcia M, Swanton B, Waggoner B, Fishel R, Franklin W, Gemmill R, et al. Distinct 3p21.3 deletions in lung cancer, analysis of deleted genes and identification of a new human semaphorin. Oncogene. 1996;12:1289–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lantuejoul S, Constantin B, Drabkin H, Brambilla C, Roche J, Brambilla E. Expression of VEGF, semaphorin SEMA3F, and their common receptors neuropilins NP1 and NP2 in preinvasive bronchial lesions, lung tumours, and cell lines. J Pathol. 2003;200:336–347. doi: 10.1002/path.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang R, Davalos AR, Hensel CH, Zhou XJ, Tse C, Naylor SL. Semaphorin 3F gene from human 3p21.3 suppresses tumor formation in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2637–2643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler O, Shraga-Heled N, Lange T, Gutmann-Raviv N, Sabo E, Baruch L, Machluf M, Neufeld G. Semaphorin-3F is an inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1008–1015. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomizawa Y, Sekido Y, Kondo M, Gao B, Yokota J, Roche J, Drabkin H, Lerman H, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis after reexpression of 3p21.3 candidate tumor suppressor gene SEMA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13954–13959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231490898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tse C, Xiang RH, Bracht T, Naylor SL. Human semaphorin 3B (SEMA3B) located at chromosome 3p21.3 suppresses tumor formation in an adenocarcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 2002;62:542–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 1996;274:1123–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams RH, Lohrum M, Klostermann A, Betz H, Puschel AW. The chemorepulsive activity of secreted semaphorins is regulated by furin-dependent proteolytic processing. EMBO J. 1997;16:6077–6086. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagnard D, Lohrum M, Uziel D, Puschel AW, Bolz J. Semaphorins act as attractive and repulsive guidance signals during the development of cortical projections. Development. 1998;125:5043–5053. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnard D, Thomasset N, Lohrum M, Puschel AW, Bolz J. Spatial distributions of guidance molecules regulate chemorepulsion and chemoattraction of growth cones. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1030–1035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01030.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kantor JD, McCormick B, Steeg PS, Zetter BR. Inhibition of cell motility after nm23 transfection of human and murine tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1971–1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puschel AW, Adams RH, Betz H. Murine semaphorin D/collapsin is a member of a diverse gene family and creates domains inhibitory for axonal extension. Neuron. 1995;14:941–948. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotz M, Novak N, Bastmeyer M, Bolz J. Membrane-bound molecules in rat cerebral cortex regulate thalamic innervation. Development. 1992;116:507–519. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagnard D, Vaillant C, Khuth ST, Dufay N, Lohrum M, Puschel AW, Belin MF, Bolz J, Thomasset N. Semaphorin 3A-vascular endothelial growth factor-165 balance mediates migration and apoptosis of neural progenitor cells by the recruitment of shared receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3332–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03332.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter J, Kern-Veits B, Huf J, Stolze B, Bonhoeffer F. Recognition of position-specific properties of tectal cell membranes by retinal axons in vitro. Development. 1987;101:685–696. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiscox S, Parr C, Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. Inhibition of HGF/SF-induced breast cancer cell motility and invasion by the HGF/SF variant NK4. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:245–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1006348317841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiscox S, Jiang WG. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor disrupts epithelial tumour cell-cell adhesion: involvement of betacatenin. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieman MT, Prudoff RS, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. N-cadherin promotes motility in human breast cancer cells regardless of their E-cadherin expression. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:631–644. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran NL, Nagle RB, Cress AE, Heimark RL. N-cadherin expression in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. An epithelial-mesenchymal transformation mediating adhesion with stromal cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:787–798. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavallaro U, Schaffhauser B, Christofori G. Cadherins and the tumour progression: is it all in a switch? Cancer Lett. 2002;176:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavallaro U, Christofori G. Cell adhesion and signalling by cadherins and Ig-CAMs in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:118–132. doi: 10.1038/nrc1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, Takegahara N, Suto F, Kamei J, Aoki K, Yabuki M, Hori M, Fujisawa H, et al. Dual roles of Sema6D in cardiac morphogenesis through region-specific association of its receptor, Plexin-A1, with off-track and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2. Genes Dev. 2004;18:435–447. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pozas E, Pascual M, NguyenBaCharvet KT, Guijarro P, Sotelo C, Chedotal A, Del Rio JA, Soriano E. Age-dependent effects of secreted Semaphorins 3A, 3F, and 3E on developing hippocampal axons: in vitro effects and phenotype of Semaphorin 3A (-/-) mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:26–43. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eickholt B, Mackenzie S, Graham A, Walsh F, Doherty P. Evidence for collapsin-1 functioning in the control of neural crest migration in both trunk and hindbrain regions. Development. 1999;126:2181–2189. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giger RJ, Urquhart ER, Gillespie SK, Levengood DV, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity. Neuron. 1998;21:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bauer A, Lickert H, Kemler R, Stappert J. Modification of the E-cadherin-catenin complex in mitotic Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28314–28321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamei T, Matozaki T, Sakisaka T, Kodama A, Yokoyama S, Peng YF, Nakano K, Takaishi K, Takai Y. Coendocytosis of cadherin and c-Met coupled to disruption of cell-cell adhesion in MDCK cells—regulation by Rho, Rac and Rab small G proteins. Oncogene. 1999;18:6776–6784. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le TL, Yap AS, Stow JL. Recycling of E-cadherin: a potential mechanism for regulating cadherin dynamics. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:219–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fournier AE, Nakamura F, Kawamoto S, Goshima Y, Kalb RG, Strittmatter SM. Semaphorin 3A enhances endocytosis at sites of receptor-F-actin colocalization during growth cone collapse. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:411–422. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castellani V, Falk J, Rougon G. Semaphorin3A-induced receptor endocytosis during axon guidance responses is mediated by L1 CAM. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhee J, Mahfooz NS, Arregui C, Lilien J, Balsamo J, VanBerkum MF. Activation of the repulsive receptor Roundabout inhibits N-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:798–805. doi: 10.1038/ncb858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dallol A, Morton D, Maher ER, Latif F. SLIT2 axon guidance molecule is frequently inactivated in colorectal cancer and suppresses growth of colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1054–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hajra KM, Fearon ER. Cadherin and catenin alterations in human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:255–268. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan J, Mansfield SG, Redmond T, GordonWeeks PR, Raper JA. The organization of F-actin and microtubules in growth cones exposed to a brain-derived collapsing factor. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:867–878. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eickholt BJ, Walsh FS, Doherty P. An inactive pool of GSK-3 at the leading edge of growth cones is implicated in Semaphorin 3A signaling. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:211–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Lin X, Wendt MA, Chadborn NH, Eickholt AM, Mercurio AM. Competing autocrine pathways involving alternative neuropilin-1 ligands regulate chemotaxis of carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5230–5233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]