Abstract

Chip profiling of a p53 temperature-sensitive tumor model identified SAK (Snk/Plk-akin kinase), encoding a new member of polo-like kinases (PLKs), as a gene strongly repressed by wild-type p53. Further characterization revealed that SAK expression was downregulated by wild-type p53 in several tumor cell models. Computer search of a 1.7-kb SAK promoter sequence revealed three putative p53 binding sites, but p53 failed to bind to any of these sites, indicating that SAK repression by p53 was not through a direct p53 binding to the promoter. Transcriptional analysis with luciferase reporters driven by SAK promoter deletion fragments identified SP-1 and CREB binding sites, which together conferred a two-fold SAK repression by p53. However, the repression was not reversed by cotransfection of SP-1 or CREB, suggesting a lack of interference between p53 and SP-1 or CREB. Significantly, p53-mediated SAK repression was largely reversed in a dose-dependent manner by Trichostatin A, a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, suggesting an involvement of HDAC transcription repressors in SAK repression by p53. Biologically, SAK RNA interference (RNAi) silencing induced apoptosis, whereas SAK overexpression attenuated p53-induced apoptosis. Thus, SAK repression by p53 is likely mediated through the recruitment of HDAC repressors, and SAK repression contributes to p53-induced apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, p53, polo-like kinase, RNAi silencing, transcription repression

Introduction

In response to DNA damage or other cellular stresses, p53 is activated and induces growth arrest or apoptosis, depending on the severity of the damage and the cell context, which tends to maintain genome stability and prevent cancer development [1,2]. p53 is a transcription factor, and it achieves these functions mainly through its transactivation as well as transrepression of its downstream target genes [3,9]. The ability of p53 to induce growth arrest is usually mediated through transactivation of several critical target genes, such as Waf-1/p21, 14-3-3σ, and PTGF-β [4–7], for G1 and G2 arrest. However, p53 induces apoptosis by transactivation of selected target genes involved in the mitochondrial or death receptor signal pathways in a tissue- and cell type-specific manner [8,9]. The p53 downstream target genes involved in the mitochodrial signal pathway include BAX, PIGs, NOXA, PUMA, p53AIP, [10–15] and in the death receptor pathway include KILLER/DR5, FAS/APO1, and PIDD [16–18]. In addition, p53 has been shown to negatively regulate cell survival genes such as survivin, IGF1R, and bcl-2 [19–21] with a net outcome of facilitating apoptosis induction.

It has been well demonstrated that p53 transactivates its targets through a direct binding to its consensus sequence, consisting of two repeats of 10-bp motif 5′-PuPuPuC(A/T)(T/A)GPyPyPy-3′ separated by 0 to 13 nucleotides, located in the promoter region or the first few introns of a target gene [31]. In contrast, p53 consensus binding sites are not found within a vast majority of promoters repressed by p53, although a recent report showed that p53 repressed the MDR1 promoter through a direct binding to a novel p53 binding site RRRCWRRRCW N(0–13) RRRCWRRRCW [22].

In an attempt to identify genes responsive to p53-induced apoptosis, we profiled H1299 human lung carcinoma cells with the Affymatrix U95 gene chip [23] and report here a novel p53-repressed gene, SAK (Snk/Plk-akin kinase), which encodes a new polo-like kinase (PLK). Murine SAK was originally cloned as a homolog to Drosophila polo kinase involved in cell proliferation [24]. Constitutive expression of murine SAK suppressed cell growth and induced multinucleation [25]. Knockout SAK produced embryonic lethality. The SAK-/- embryo at E8.5 is smaller than wild-type or heterozygous littermates. The embryo is arrested with an increase both in mitotic and apoptotic cells [26]. Human SAK that is highly expressed in testis was cloned in 1997 [27] and was recently found to have kinase activity and to be tyrosine-phosphorylated by Tec tyrosine kinase [36]. Human SAK was highly expressed in colon cancers, compared to adjacent normal intestinal mucosa [35].

We found that downregulation of SAK expression is p53-dependent. p53-induced SAK repression is neither mediated through direct binding to its consensus sequences nor through an interference of p53 with other transcription factors, but rather through the recruitment of histone deacetylase (HDAC) repressor. Biologically, SAK silencing by RNAi induces apoptosis, whereas SAK overexpression attenuates p53-induced apoptosis, suggesting that SAK repression contributes to p53-induced apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatment

H1299-V138, a human lung carcinoma cell line transfected with a temperature-sensitive mutant p53 (containing an alanine-to-valine point mutation), and its vector control (H1299/Neo) were kindly provided by Gr. Jiandong Chen (H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL) [28]. The H460 lung carcinoma line and H460/E6 (stably transfected with the human papilloma virus E6 gene) were obtained from Dr. Wafik El-Deiry (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). All other cell lines used in the study were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The parental lung carcinoma H1299 and H460, as well as HeLa cells, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), whereas H1299-V138, H1299/Neo, and H460/E6 cells were cultured in the same medium plus 0.75 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). The human osteosarcoma U2-OS and Saos-2 cells were grown in McCoy's 5a medium with 10% FBS (Invitrogen). All culture media were supplemented with 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen). To change p53 conformation, the culture temperature for H1299-V138 and H1299/Neo was either 39°C (nonpermissive for wild-type p53 conformation) or 32°C (permissive for wild-type p53). To activate p53, cells were treated with etoposide (25 µM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for different periods of time.

Affymetrix Chip Profiling

H1299-V138 and H1299/Neo cells were grown at 37°C to ∼70% confluency and shifted to either 32°C or 39°C for 6, 16, or 24 hours in the absence or presence of 25 µM etoposide. Total RNA was isolated, then cRNA was synthesized and subjected to chip hybridization as detailed previously [23,29] using Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) human U95Av2 GeneChip A, consisting of 12,000 human genes (Affymetrix). Scanned output files were analyzed using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 4.0. The expression value for each gene was determined by calculating the average differences of the probe pairs. Fold change was expressed by dividing the expression value of each treatment to that of the corresponding control in each group, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Repression of SAK Expression under Growth Arrest and Apoptotic Conditions.

| Treatment | Conditions | p53 Status | Fold Change |

| Group 1 | p53, 6 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.0 |

| p53, 16 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.1 | |

| p53, 24 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.0 | |

| p53, 6 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | Wild type | 1.1 | |

| p53, 16 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | Wild type | -1.5 | |

| p53, 24 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | Wild type | -5.1 | |

| Group 2 | p53, 6 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.0 |

| p53, 16 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.0 | |

| p53, 24 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | Mutant | 1.1 | |

| p53, 6 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | Wild type | -1.0 | |

| p53, 16 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | Wild type | -2.2 | |

| p53, 24 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | Wild type | -3.6 | |

| Group 3 | Neo, 6 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | p53-/- | 1.0 |

| Neo, 16 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | p53-/- | -1.2 | |

| Neo, 24 hours, DMSO, at 39°C | p53-/- | -1.2 | |

| Neo, 6 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | p53-/- | -1.0 | |

| Neo, 16 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | p53-/- | -1.1 | |

| Neo, 24 hours, DMSO, at 32°C | p53-/- | -1.1 | |

| Group 4 | Neo, 6 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | p53-/- | 1.0 |

| Neo, 16 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | p53-/- | 1.1 | |

| Neo, 24 hours, etoposide, at 39°C | p53-/- | 1.0 | |

| Neo, 6 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | p53-/- | 1.2 | |

| Neo, 16 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | p53-/- | 1.1 | |

| Neo, 24 hours, etoposide, at 32°C | p53-/- | 1.1 | |

Northern Analysis

Northern analysis was performed as detailed previously [30]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol reagents (Invitrogen) and 15 µg was used for analysis. The probes for SAK and GAPDH were made by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Primers for SAK were 5′-GTGGGGAAATCAAGAAACCA-3′ and 5′-GGTGGCTCCATACCCCTAGT-3′, which generated a 699-bp fragment. Primers for GAPDH were 5′-CGAGATCCCTCCAAAATCAA-3′ and 5′-TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA-3′. These two cDNA fragments were subcloned into pCR2.1 for sequence confirmation and then used as Northern probes.

Identification of the Transcription Initiation Site and Search for Potential p53 Binding Sites in the Promoter Region

A PCR-based 5′ RACE was performed using the FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit with protocols suggested by the manufacturer (Ambion, Austin, TX). Briefly, total RNA was treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) to remove free 5′-phosphates from molecules of fragmented mRNA. The RNA was then treated with Tobacco Acid Pyrophosphatase to remove the cap structure from full-length mRNA, leaving a 5′-monophosphate. A 5′ RACE adapter oligo, 5′-GAACACTGCGTTTGCTGGCTTT GATGAAA-3′, which is specific for the 5′-monophosphate, was ligated to the RNA population using T4 RNA ligase. An RT- PCR reaction then amplified the 5′ end of the SAK mRNA using the adapter oligonucleotide and a primer from the SAK mRNA. The 5′ RACE products were cloned into pCR2.1 vectors and the insert fragments were sequenced. The transcription initiation site was determined by comparing the sequences immediately after the 5′ RACE adapter oligonucleotide to the SAK gene sequence by the evidence viewer from NCBI (Bethesda, MD). After determination of the initiation site, a region between 1.7 kb upstream of the site and 100 bp downstream of the site was searched for potential p53 binding elements. Fasta files for the region were uploaded into Unix, converted to a GCG file, and searched with the GCG program, Findpatterns. The search was conducted for p53 consensus binding elements, RRRCWWGYYY(N){0,13}RRRCWWGYYY [31], and potential p53 repressive elements, RRRCWRRRCW(N){0,13}RRRCWRRRCW, suggested by Johnson et al. [22], allowing three mismatches.

Promoter Constructs and Luciferase Reporter Assays

An 1.8-kb fragment, P-00/14, containing 1698 bp of upstream and 102 bp of downstream sequences around the transcription initiation site, was PCR-generated and subcloned into the pGL3 luciferase reporter construct (Promega, Madison, WI). This fragment served as a template for PCR to generate other deletion constructs. All constructs were transiently transfected into H1299-V138 or cotransfected with wild-type p53 expressing plasmid into the parental H1299 cells for luciferase reporter assays. Plasmid-expressing β-gal was also included for internal controls of transfection efficiency. The transfection was performed with LipofectAMINE reagent (Invitrogen), according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. The luciferase assay was performed 30 hours after transfection by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction and detected in a luminometer (MicroLumat Plus; Berthold Tech Pforzheim/Germany). For transfection in H1299-V138 cells, the incubation temperature was shifted from 39°C to 32°C, 6 hours after transfection, to allow the expression of wild-type p53. Luciferase activities were measured after a 24-hour incubation at 32°C.

For TSA treatment experiment, parental H1299 cells were transiently cotransfected with luciferase reporter constructs of P-00/14 or p-05/18 (with empty vector pGL3-basic as a control) and p53-expressing plasmid or the empty pcDNA3 vector as a control. Transfection efficiency was normalized by cotransfection with pRL-CMV, expressing Renillar luciferase (Promega). Transfection was done directly in 96-well cell culture plates with 20,000 cells/well plated in growth medium 1 day before, using LipofectAMINE 2000. Each well contained plasmids of 0.03 µg of P00/14 or p-05/18 or pGL-3, 0.18 µg of p53 or pcDNA3, and 0.001 µg of pRL-CMV. Cells were subjected to TSA (Sigma) treatment for 6 hours starting at 18 hours after transfection at various concentrations. The luciferase activities were then measured by Dual-Glo System (Promega) on a TopCount (Packard Instrument, Meriden, CT). The results from three independent experiments, with each in triplicate, were expressed as fold induction after normalization with transfection efficiency and pGL3-Basic vector control.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The EMSA was performed as described previously [32,33]. The primers used were putative p53 binding oligonucleotides found in the promoter region of SAK, including: 1) P-01 5′-AGCCTGGGCGACAGAGCGAG-3′ and its complementary strand; 2) P-03 5′-TGCCCTGTTCCGTCAAGTCT-3′ and its complementary strand; and 3) P-05 5′-GAACTAAACTCTCCGCAGCGCT-3′ and its complementary strand. The oligonucleotides containing p53 binding sites from the promoters of PTGF-β or p21 genes [5,7] served as positive controls. For supershift analysis, 1 µg of anti-p53 antibody Ab-1 (PAb421) or DO-1 was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 20 minutes before the addition of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide.

Chip PCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis used to assess potential in vivo binding of p53 to the promoter of SAK was performed as described [34,23,35]. The primer sequences and their amplifying regions are given below. The primers are in italics, and the consensus p53 binding sites or the putative p53-repressive sites [22] are underlined with core sequences in bold—for P21: GTGGCTCTGATTGGCTTTCTGGCCATCAGGAACATGTCCCAACATGTTGAGCTCTGGCATAGAAGAGGCTGGTGGCTATTTTGTCCTTGGGCTGCCTGTTTTCAG; for Mdm2: GGTTGACTCAGCTTTTCCTCTTGAGCTGGTCAAGTTCAGACACGTTCCGAAACTGCAGTAAAAGGAGTTAAGTCCTGACTTGTCTCCAGCTGGGGCTATTTAAACCATGCATTTTCC; for P-01: CCAGCTACCCGGGAGACTGAGGAAGGAGAATCGCTGGAACCCAGGAGATGGAGGCTGCAGTGAGCCGAGATCGAGTCACTGCACTCCAGCCTGGGCGACAGAGCGAG; for P-03/05 (P-03/05 contains two putative p53-repressive sites) TGCCCTGTTCCGTCAAGTCTTAAACGCTTGACATTTTAAAATAGTTTTAAACCCTTTCCGGAATTAGAAGTGGTATTTCGGACCGTGAAGTAACCGATCAGCCATAAGTGTCCCATCTTTAAGGCTGCTCTTTTACCCGTCTTGCAGAAGTTCTTCCGAGAGTGGGCCCGAGACAGCCTCCCGCCCGAACTAAACTCTCCGCAGCGCT; and for GAPDH: GTATTCCCCCAGGTTTACATGTTCCAATATGATTCCACCCATGGCAAATTCCATGGCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAACGGGAAGCTTGTCATCAATGGAAATCCCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGTGAGTGGAAGACAGAA.

SAK Silencing by RNAi

HeLa cells were seeded at 1.5 x 104 cells/well in a 12-well plate in DMEM with antibiotic-free 10% FBS. Cells were transfected from 16 to 20 hours later with RNAi Oligo, SAK1 (276–297) AAGCCATGTACAAAGCAGGAA, or SAK2 (2833–2844) AATGTTGGTTGGGCTACACAG using Oligofect AMINE Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. After 48 hours of transfection, cells in one well were harvested for RT-PCR analysis for SAK expression, and cells in a duplicate well were photographed to evaluate morphologic signs of apoptosis. RNA was isolated using Trizol reagents and reversely transcribed into cDNA using random primers (Invitrogen). The cDNA was amplified using SAK-specific primers PB01 5′-CACCCACAGACAACA ATGCC-3′ and PB02 5′-CTCCATACCCCTAGTCTTGCTC-3′ to generate a 470-bp fragment. For loading control, a 253-bp fragment was amplified using primers PBGD-283F 5′-GAGAAGAATGAAGTGGACCT-3′ and PBGD 536R 5′-AGGTTTCCCCGAATACTCC-3′ for gene-encoding porphobilinogen deaminase [35].

Establishment of SAK Stable Clones

A plasmid construct expressing FLAG-tagged human SAK was a gift from Dr. Mano [36] and transfected into U2-OS cells harboring a wild-type p53 [7]. Transfected cells were subjected to G418 (600 µg/ml) selection for 2 weeks and a total of 12 stable clones was isolated by ring cloning, followed by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) to identify SAK-expressing clones, as described previously [37].

DNA Fragmentation ELISA

Apoptosis was measured by DNA fragmentation-based Cell Death ELISA Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, HeLa cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and cultured for 16 to 24 hours before being transfected with different amounts of SAK RNAi K1 or K2. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, both detached and attached cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed in 200 µl of lysing buffer by shaking at room temperature for 30 to 40 minutes. Following centrifugation, 20 µl of supernatant was used for the assay and read at OD405 nm.

DNA Fragmentation Gel Analysis

Two SAK-expressing stable clones, along with one vector control, were treated with etoposide (25 µM) for 36 hours to activate p53 [7]. Both detached and attached cells were collected, lysed, and subjected to DNA fragmentation assay as described previously [38].

Results

Chip Profiling Identified SAK as a p53-Repressive Gene

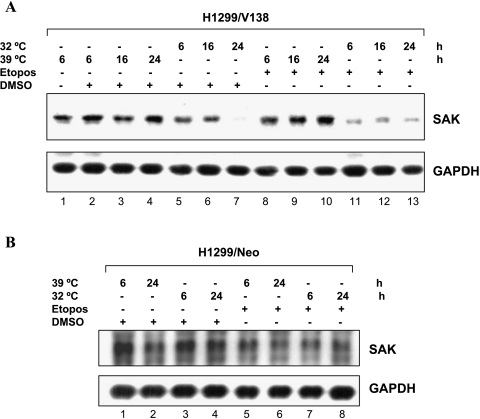

In an effort to identify genes responsive to p53-induced growth arrest and/or apoptosis, we performed an Affymetrix Genechip analysis of 12,000 genes (Human U95 Genechip A; Affymetrix) using mRNA isolated from human H1299-V138 cells expressing a temperature-sensitive p53 mutant. p53 adapts a mutant conformation when cells are grown at a nonpermissive temperature of 39°C but a wild-type conformation at the permissive temperature of 32°C, which causes cell growth arrest or apoptosis when given DNA-damaging agents, such as etoposide [23,28]. H1299/Neo cells that underwent neither growth arrest nor apoptosis at 32°C were used as controls. Among 133 differentially expressed genes that respond to both growth arrest and apoptosis conditions, a new member of the PLK family, SAK (GenBank accession no. Y13115 or MN_014264) was identified to be significantly repressed by p53. The expression of this gene was not changed in H1299/Neo cells under the same growth conditions (Table 1). To confirm this finding, Northern analysis was performed using SAK cDNA as a probe. As shown in Figure 1A, SAK mRNA was highly expressed in growing cells at 39°C (lane 1). SAK expression started to decrease as early as 6 hours after shifting the temperature from 39°C to 32°C to induce wild-type p53 conformation in either the absence or presence of etoposide (lanes 5–7 and 11–13). SAK expression was not significantly changed in H1299-Neo cells by the same treatment (Figure 1B), indicating that the repression of SAK expression did not result simply from temperature shifting nor from etoposide exposure. Because temperature shift did not change p53 expression, but p53 activity in this transfected line [39], these results, therefore, suggest that SAK could be repressed by a functional p53.

Figure 1.

Wild-type p53-dependent repression of SAK expression. H1299-V138 (A) or H1299/Neo (B) cells were grown either at 39°C (mutant p53 status) or 32°C (wild-type p53 status) for 6, 16, and 24 hours in the presence of DMSO or etoposide (25 µM) as indicated. Cells were harvested and RNA were prepared for Northern analysis (15 µg of total RNA) using probes against SAK. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

SAK Repression Was p53-Dependent

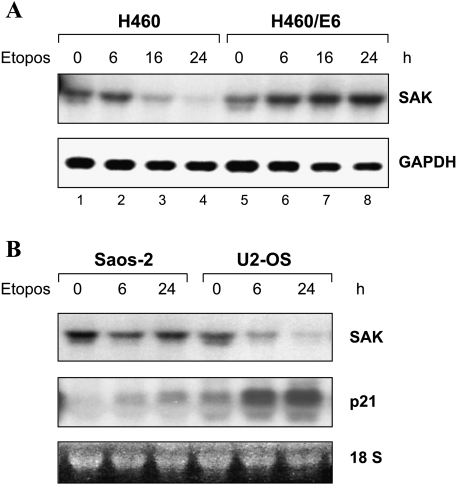

We then used two additional human tumor cell models to assess more directly the role of p53 in the downregulation of SAK. H460 lung carcinoma cells contain wild-type p53, whereas H460/E6 are p53 negative due to the expression of the human papilloma virus type 16 (HPV-16) E6 gene that degrades p53 through a ubiquitin pathway [40]. Both H460 and H460/E6 cells were treated with etoposide for up to 24 hours to activate p53, followed by RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, basal SAK level was quite high in both cell lines. Treatment with etoposide dramatically decreased SAK expression in a time-dependent manner in p53-positive H460 cells, but not in p53-negative H460/E6 cells, indicating a direct relationship between p53 status and downregulation of SAK expression. The second pair of tumor cell model used was U2-OS (wild-type p53) and Saos-2 (p53-null) human osteogenic sarcoma cell lines. Treatment with etoposide caused, as expected, an induction of p21 in U2-OS cells but not in Saos-2 cells, indicating the activation of p53 by etoposide only in the U2-OS cells (Figure 2B). In contrast to p21 induction, the SAK expression was significantly repressed at 6 hours and further repressed at 24 hours in U2-OS cells, whereas no significant change in SAK expression was observed in Saos-2 cells. Taken together, the results strongly suggested that downregulation of SAK expression is p53-dependent.

Figure 2.

SAK repression is p53-dependent. (A) Human lung carcinoma line, H460 (wild-type p53), and its E6 transfectant, H460/E6 (p53-negative due to E6-mediated p53 degradation), and (B) human osteogenic sarcoma lines, Saos-2 (p53-null) and U2-OS (wild-type p53), were treated with etoposide (25 µM) for 0, 6, and 24 hours to activate p53. Cell pellets were subjected to RNA isolation and Northern analysis (15 µg of total RNA) using probes against SAK or p21. The 18S ribosomal RNA was used as a loading control.

Lack of a Direct Binding of p53 to Several Putative Binding Sites in the SAK Promoter

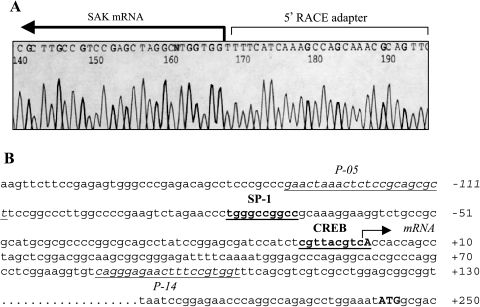

To clone the SAK promoter for a direct analysis of transcriptional regulation of SAK by p53, we first identified the transcriptional initiation site of the gene through a 5′ end RACE experiment (Materials and Methods section). Sequencing analysis of 5′ end RACE clones revealed that the longest piece of the 5′ untranslated region of the gene ended with a “T,” as indicated in Figure 3A. The results suggested a transcriptional initiation site of “A” located at 242 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon in the human SAK promoter (Figure 3B). A nucleotide “A,” which is located 303 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon, was reported in mouse SAK promoter [41]. Based on the published human genomic sequence around the SAK gene, a pair of primers, P-00/P14, was designed to PCR-amplify a 1800-bp genomic fragment with 1.7 kb in the promoter region and 100 bp downstream of the transcriptional initiation site (Figure 5A).

Figure 3.

5′ RACE used to determine the transcriptional initiation site of the SAK gene. (A) Sequence demonstration of transcription initiation site of the SAK gene. 5′ RACE was performed with Ambion's FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transcription initiation site was determined by comparing the sequences immediately after the 5′ RACE adapter (5′-GAACACTGC GTTTGCTGGCTTTGATGAAA-3′) to the SAK gene sequence through the evidence viewer from NCBI. The SAK mRNA start was indicated. (B) DNA sequence of -171 to +250 of the SAK gene. The bold “A” and “ATG” indicate the transcription initiation site (+1) and the translation starting codon, respectively. The potential SP-1 and CREB binding sites are in bold face and underlined.

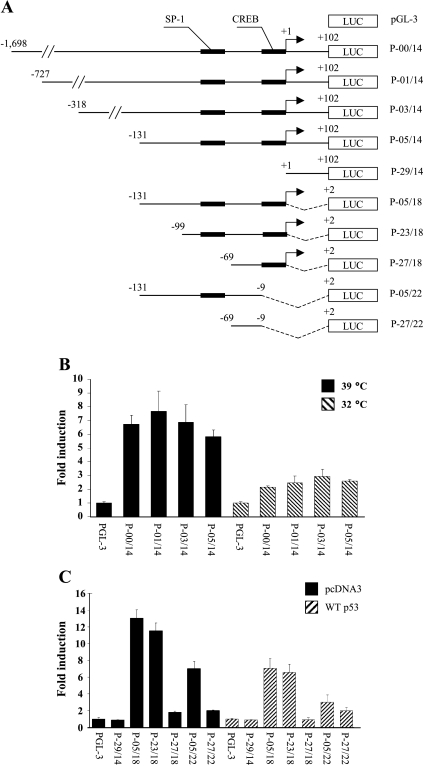

Figure 5.

Define the responsive elements in the SAK promoter to p53-induced SAK repression. (A) Diagram to show a series of luciferase reporters driven by a different length of SAK promoter sequence. An arrow at position +1 indicates the transcription initiation site. SP-1 and CREB binding sites in the proximal region of the transcription start site are shown as filled bars. (B) p53 represses SAK promoter activity. H1299-V138 cells were transiently transfected with various luciferase reporter constructs as indicated followed by incubation at 39°C or 32°C for 24 hours before being harvested for luciferase activity assay. Shown are fold activation of promoter constructs in either the presence or absence of wild-type p53, normalized to the activation of the pGL-3 empty vector. Results are from three independent transfections, each performed in duplicate and expressed as mean ± SEM. (C) SP-1 and CREB binding sites mediated by two-fold repression of the SAK promoter. Parental H1299 cells were cotransfected with either wild-type p53 or pcDNA3 vector control, plus various luciferase constructs as indicated. Twenty-four hours following transfection, cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase activity. The bar graph shows fold activation of various constructs when compared with the empty luciferase construct, pGL-3, from three independent transfections, each performed in duplicate and expressed as mean ± SEM.

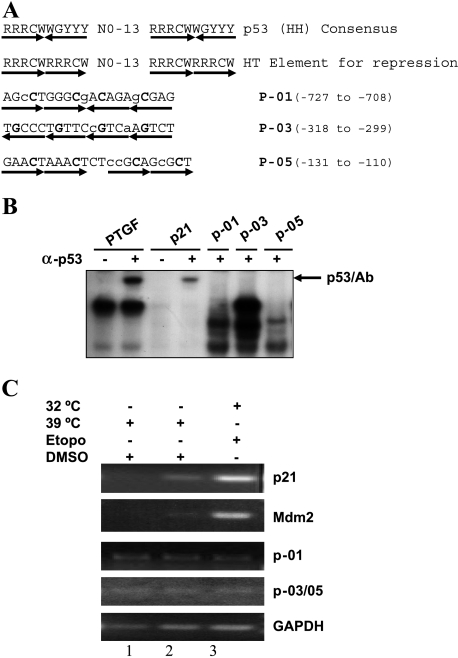

p53 usually transactivates its target genes through a direct binding to the consensus binding sequence either in the gene promoter or the introns [42]. It is still unclear whether p53-induced gene repression requires a direct binding or indirect recruiting of p53 to a promoter region. A novel p53 binding element for repression of a gene has been recently described, which contains similar p53 consensus binding sequences but in a different orientation [22]. A computer search, allowing up to three mismatches, for possible p53 binding sites of either the typical consensus site or the novel element identified three sequence elements at the promoter region of the SAK gene (Figure 4A). To determine the potential binding of p53 to these sites, we performed gel mobility shift assay using nuclear extracts prepared from H1299-V138 cells grown at 32°C in the presence of etoposide. Two known p53 binding elements from promoters of the PTGF-β gene and the p21 gene, respectively, were used as positive controls [5,7]. As shown in Figure 4B, p53 bound specifically to the PTGF-β and p21 sites, but not to any of the putative sites found in the SAK promoter. In addition, partially purified p53 protein [32] or nuclear extract prepared from etoposide-treated H460 cells also failed to bind to these sites (data not shown), indicating a lack of direct p53 binding to these sites in vitro. We also performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays to determine whether p53 binds to these sites in vivo. As shown in Figure 4C, p53 bound to its consensus sequence found in the p21 and Mdm2 genes when it adapted a wild-type conformation (32°C) in the presence of etoposide in H1299-V138 cells. No significant signal of p53 binding to those sites found in the SAK promoter was detected under the same assay conditions. Furthermore, promoter walking using additional primer pairs that covered the entire region from the transcription initiation site up to nucleotide -1033 failed to detect any p53 binding (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicated that p53 does not interact with putative binding sites found in the promoter of SAK, implying that p53 may indirectly control SAK expression.

Figure 4.

p53 failed to bind to three putative p53 binding sites in the SAK promoter. (A) Listed are the sequences of the p53 consensus binding site for activation (line 1) and repression (line 2) [23] and three putative p53 binding sites within the SAK promoter region (lines 3–5). R = purine, Y = pyrimidine, W = A/T, H = head, T = tail. The mismatches in SAK promoter sequences are indicated with lower case letters and the core sequences are indicated in bold face. (B) In vitro gel retardation assay. The assay was performed as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. The probe PTGF (5′-AGCCATGCCCGGGCAAGAAC-3′) and its complementary strand from the promoter of the PTGF-β gene [54], and p21 (5′-GAACATGTCCCAACATGTTG-3′) and its complementary strand from the promoter of p21 gene [11], were used as positive controls in the assay. p53/Ab indicates the supershifted complex in the presence of p53 antibody, pAb421. (C) In vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation. p21 and Mdm2 are used as positive controls, and GAPDH is used as a negative control. Since two putative p53 binding sites, P-03 and P-05, are adjacent to each other, only one pair of PCR primers was used to detect potential p53 binding to any one of them. Total cell extracts were prepared from H1299/Neo (lane 1) and H1299-V138 (lanes 2 and) cells treated with either DMSO or 25 µM etoposide for 24 hours at 39°C or 32°C. The assays were performed as detailed in the Materials and Methods section.

p53-Induced SAK Repression Is Unlikely Mediated through an Interference of p53 with Transcription Factors, SP-1 and CREB

To understand the mechanism of repression, we made a series of promoter luciferase constructs in an attempt to identify the repression-responsive region in the SAK promoter. The 1.8-kb fragment generated by a primer set of P-00/P14 was used as a template to prepare other deletion constructs, as presented in Figure 5A. H1299-V138 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter driven by a different length of SAK promoter sequence. After transfection, cells were grown at 32°C for 24 hours to induce wild-type p53 conformation, followed by luciferase assay. As shown in Figure 5B, wild-type p53 induced an up to three-fold reduction of luciferase activity. Because the degree of reduction of luciferase activity was similar between constructs P-00/P14 and P-05/P14, the promoter sequence flanking -1698 to -131 contributed little to p53-induced repression. Thus, the responsive cis elements are likely located within the proximal region of nucleotides -131 to +102. To define the cis element(s), we performed a computer search for potential transcription factor binding sites. The putative binding sites of SP-1 and CREB were identified, among several others, such as NRF1 and NRF2. A series of deletion luciferase reporters was generated, as shown in Figure 5A, with SP-1 and CREB sites indicated and tested for their p53-dependent activity. As expected, no luciferase activity and p53 repression was detected with the construct P-29/14-luc due to lack of promoter sequence (Figure 5C). This further narrowed down the responsive element(s) to the upstream 131-bp promoter sequence. A 12-fold basal activity and a similar two-fold repression by p53 seen in constructs P-05/18-luc and P-23/18-luc indicated that the promoter sequence between -131 and -100 did not contribute to SAK regulation. Deletion of SP-1 binding site alone almost completely abolished the promoter activity (from 12- to 2-fold) as seen in construct P-27/18-luc, indicating a requirement of the SP-1 factor for basal transcriptional activity. However, the luciferase activity driven by this fragment was still repressed by up to two-fold by p53. Deletion of CREB site alone caused a two-fold reduction of basal transcriptional activity (from 12- to 6-fold), but again a further two-fold repression by p53, as shown in construct P-05/22-luc. Deletion of both SP-1 and CREB sites, as seen in construct P-27/22-luc, reduced basal activity from 12- to 2-fold, and p53 had no repressive effect (Figure 5C). Thus, it appeared that two-fold repression of the SAK promoter by p53 required the presence of both SP-1 and CREB binding sites. To further investigate the possibility that p53-induced repression of the SAK promoter may be mediated through an interference of p53 with transcription factors SP-1 and CREB for their binding to respective binding sites, we performed cotransfection experiments using luciferase reporters driven by P-00/14, P-23/18, or P-05/18 and plasmids expressing SP-1 or CREB in combination with p53. Cotransfection of neither SP-1 nor CREB reversed p53-induced two-fold reduction of SAK promoter activity (data not shown), indicating that interference of p53 with transcription factors SP-1 or CREB is unlikely a direct cause of SAK repression by p53. However, these two binding sites could be a part of cis elements required for basic transcription machinery to bind for basal promoter activity as well as for p53 repression.

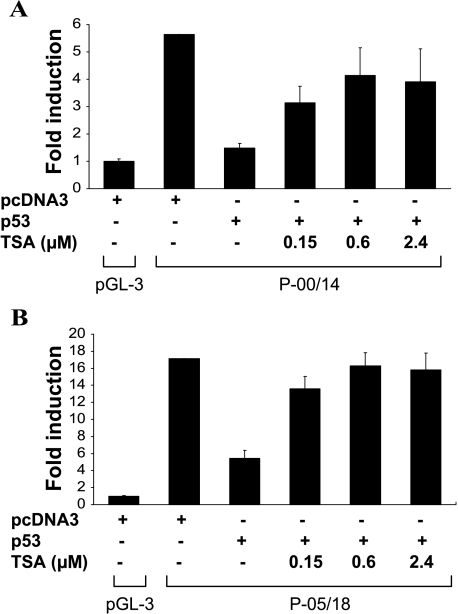

p53-Induced SAK Repression Can Be Rescued by the HDAC Inhibitor, TSA

It has been previously shown that p53 can directly interact with some factors of the basal transcription machinery such as TBP [43,21], which facilitates a recruitment of the mSin3a/HDAC repressor complex to repress the transcription [44], and such repression can be reversed with an HDAC inhibitor in the case of p53 repression of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) [45]. To determine the possible involvement of HDAC in p53-mediated SAK repression, we use luciferase reporters driven either by a 1.8-kb promoter fragment (P-00/14) or a 131-bp fragment (P-05/18), which showed the highest promoter activity. The reporter constructs were cotransfected with p53 into parental H1299 cells, followed by treatment with Trichostatin A (TSA) with various concentrations for 6 hours. As shown in Figure 6A, p53-induced ∼3.5-fold repression of a 1.8-kb SAK promoter activity can be largely reversed by TSA in a dose-dependent (up to 0.6 µM) manner. More significantly, the 131-bp SAK promoter repression by p53 was completely reversed by TSA, again in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6B). Thus, it appeared that SAK promoter repression by p53 is mainly mediated through a p53-mediated recruitment of HDAC transcription repressor.

Figure 6.

TSA rescued SAK repression by p53. Parental H1299 cells were plated in a 96-well plate and transfected with luciferase reporters driven either by a 1.8-kb SAK promoter (P-00/14) (A) or a 131-bp promoter fragment (P-05/18) (B) in the absence or presence of p53, along with pRL-CMV, which expressed Renillar luciferase for transfection efficiency control, as described previously [54]. Eighteen hours posttransfection, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TSA for 6 hours. Cells were lysed in a plate and subjected to luciferase assay. Results from three independent transfections, each in triplicate, were presented as mean ± SEM after normalization with the empty luciferase vector, pGL3-basic, and pRL-CMV controls.

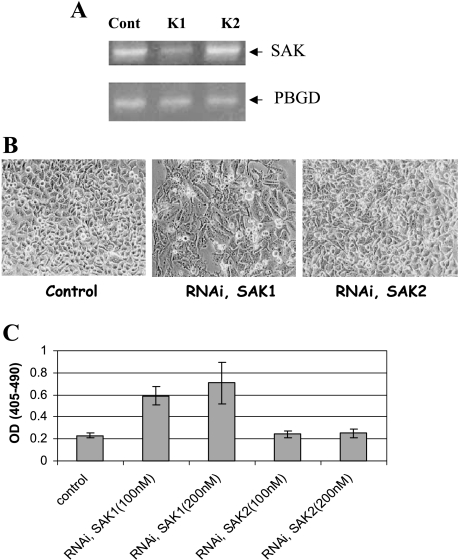

SAK Silencing by RNAi induced Apoptosis

To understand the biologic significance of SAK repression by p53 during apoptosis, we knocked down SAK expression using RNAi and looked for phenotype changes. HeLa cells were transfected with two SAK RNAi (K1 and K2). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were harvested, RNA were prepared, and SAK expression was determined by RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 7A, K1, but not K2, caused a significant reduction of endogenous SAK expression. Accompanying the SAK reduction, morphologic signs of apoptosis appeared in K1-transfected, but not K2-transfected, cells (Figure 7B). Quantitative DNA fragmentation assay showed that indeed K1, but not K2, RNAi induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7C). Thus, SAK repression likely contributes to p53-induced apoptosis.

Figure 7.

SAK silencing through RNAi-induced apoptosis. HeLa cells were left untransfected or transfected with two individual RNAi oligonucleotides (200 nM), K1 and K2, by oligofectamine for 48 hours, followed by RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis with a housekeeping gene PBGD as the loading control (A), or morphological observation for sign of apoptosis (B), and DNA fragmentation ELISA (C).

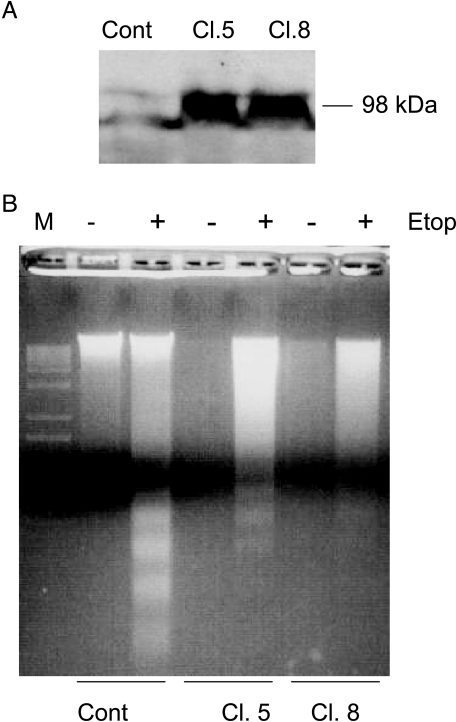

SAK Overexpression Attenuated p53-Induced Apoptosis

If SAK repression is critical for p53-mediated apoptosis induction, one would expect that overexpression of SAK should block or attenuate p53 effect. To test this hypothesis, we went on to establish SAK stable lines by transfecting a plasmid-expressing FLAG-SAK into wt p53-containing U2-OS cells, along with the vector control. After G418 selection, we isolated 12 stable clones by ring cloning and tested their SAK expression by Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG antibody. As shown in Figure 8A, two independent positive clones (Cl. 5 and Cl. 8) expressed an expected size of SAK band at 98 kDa [36], compared to vector control clones. Other 10 stable clones failed to express SAK (data not shown). These three clones were then subjected to etoposide treatment to induce p53 as shown previously [46,7], followed by a gel assay for DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of apoptosis. As shown in Figure 8B, etoposide treatment significantly induced DNA fragmentation in U2-OS vector control cells. The degree of DNA fragmentation was significantly reduced in both SAK-overexpressing clones, indicating that SAK overexpression attenuates p53-induced apoptosis.

Figure 8.

SAK overexpression attenuated p53-induced apoptosis. (A) Establishment of SAK stably expressing clones: U2-OS (p53-wt) cells were transfected with plasmid-expressing FLAG-tagged SAK, along with the pcDNA3 vector control. Stable clones were isolated after G418 selection and ring cloning. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody. Two independent clones (Cl. 5 and Cl. 8) with SAK expression as a 98-kDa band were shown, along with a vector control. (B) SAK overexpression attenuated p53-induced apoptosis: three stable lines, shown in (A), were subjected to etoposide (25 µM) treatment for 36 hours to induce p53 or left untreated. Both attached and detached cells were harvested and subjected to DNA fragmentation gel assay. Induction of DNA fragmentation by etoposide-activated p53 was obviously seen in the control cells, but to a much lesser extent, in two SAK-overexpressing clones.

Discussion

Proposed mechanisms for p53-induced gene repression fall into three general categories. Firstly, p53 may directly bind to a promoter through either a consensus binding site [22] or other sites that are overlapped with some cis elements such as E2F, SP-1, or HNF3, which are required for transactivation of the gene [19,47,48]. Secondly, p53 may interact with a transcription factor in the promoter and interfere with its normal function of transactivation. Examples include p53 repression of Cdc2, cyclin B, and Cdc25C by interaction with NF-Y [49,50]; p53 downregulation of human MMP1 and metastasis-associated laminin receptor promoters through AP-1 and AP-2, respectively [51,52]; and p53 inhibition of the albumin gene and the glycoprotein hormone common a subunit gene through C/EBPβ and CBP/p300, respectively [53,54]. Thirdly, p53 may directly interact with some factors of the basal transcription machinery such as TBP [43,21]. The binding of p53 to these factors could recruit an HDAC complex to the minimal promoter region and cause a repression of transcription [44]. Such repression may be reversed in the presence of HDAC inhibitors [45].

Through chip profiling, we have identified SAK, a PLK, as a p53-repressed gene. We further validated that SAK is indeed repressed by p53 in multiple human tumor models using a classic Northern analysis. Although three p53 consensus binding sites were identified in the SAK gene promoter, p53 failed to bind to any of these sites as assayed by in vitro gel retardation assay and in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation. Further characterization of SAK promoter through transcription-coupled luciferase assay revealed that p53 repression of SAK expression cannot be reversed by cotransfection of SP-1 and CREB, although these two transcription factor binding sites appeared to mediate a two-fold SAK repression by p53. However, p53 repression of SAK promoter can be largely reversed by TSA, a potent inhibitor of HDACs. Thus, SAK repression by p53 is not mediated through direct promoter binding, unlikely through interference of p53 with SP-1 and CREB, but rather through the recruitment of HDAC transcriptional repressors.

SAK belongs to a PLK family with other members including PLK1, PLK2/Snk, and PLK3/Fnk/Prk. The PLKs are known to play pivotal roles in cell cycle regulation, specifically in the control of entry and exit of mitosis [55–57]. Like other family members, SAK contains a Ser/Thr kinase domain at the N-terminus and one highly conserved polo box at the C-terminus of the protein [26,58]. SAK expression appeared to be required for cellular exit from mitosis through the APC-dependent inactivation of the Cdc2/cyclin B complex [26]. It has been previously shown that SAK expression was subjected to cell cycle regulation in NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells [24]. We performed a similar experiment in H1299-Neo epithelial-originated cancer cells by arresting cells at the G2/M phase with nocodazole for 16 hours, followed by cell release from the G2/M phase by growth in fresh serum-containing media. Cells were collected at 3, 6, 8, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 hours post-nocodazole release. The cell samples were split into two portions: one portion was for FACS analysis to monitor cell cycle progression, whereas the other portion was for RNA isolation, followed by RT-PCR analysis to monitor SAK expression. FACS analysis revealed that cells started to enter the G1 phase 3 hours post-nocodazole release and reached the peak at 8 hours. Cells started to enter the S phase 16 hours post release and reached the peak at 22 hours. In all cell samples collected, no significant change in SAK expression was observed (data not shown). Thus, SAK expression appeared not to be subjected significantly to cell cycle regulation in H1299 lung carcinoma cells.

It has been previously reported that inhibition of SAK expression using antisense murine SAK suppressed the cell growth of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells [24], whereas transient overexpression of SAK induced multinucleation and resulted in suppression of CHO cell growth as well [25]. Thus, it appears that the SAK expression level is crucial for cell growth. It has also been reported that changes of intracellular levels of other PLKs were also involved in the control of cell growth. For example, PLK1, when fused to an antennapedia peptide and efficiently internalized into cells, caused an inhibition of cancer cell proliferation [59], whereas downregulation of PLK1 by antisense induced the growth inhibition of cancer cells [60]. Inhibition of PLK1 activity also contributed to apoptosis induced by β-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin, a plant isolate [61]. Furthermore, PLK3 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through perturbation of microtubule integrity [62]. Moreover, PLK2 was recently found to be a novel p53 target gene, and that RNAi silencing of PLK2 leads to mitotic catastrophe in taxol-exposed cells [63]. Finally, and most importantly, a recent report showed that PLK1 was also repressed by p53 in a direct binding-independent manner, and that RNAi silencing of PLK1 induced apoptosis [64], which is consistent with our observation in SAK. In addition, PLK1 was found to actually bind to p53 and block p53-induced apoptosis [65], consistent with our observation that SAK overexpression attenuated p53-induced apoptosis. Taken together, SAK, like its family member PLK1, can regulate p53 apoptosis function, and its downregulation may be necessary for p53 to induce apoptosis. Thus, SAK appears to be a promising cancer target for p53-dependent induction of apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiroyuki Mano (Jichi Medical School, Tochigi, Japan) for the FLAG-SAK construct, Guntram Suske (Institute of Molecular Biology and Tumor Research, Philipps-University, Mannkopff-Strasse, Germany) for the SP1 construct, and Hua Lu (Oregan Health Science University, Portland, OR) for the CREB construct.

Abbreviations

- CREB

cAMP-responsive element binding

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- PLK

polo-like kinase

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SAK

Snk/Plk-akin kinase

- TSA

Trichostatin A

References

- 1.Giaccia AJ, Kastan MB. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko LJ, Prives C. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1054–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan TA, Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3s is required to prevent mitotic catastrophe after DNA damage. Nature. 1999;401:616–620. doi: 10.1038/44188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.el Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He TC, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3 Sigma is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan M, Wang Y, Guan K, Sun Y. PTGFb, a type b transforming growth factor (TGFb) superfamily member, is a p53 target gene that inhibits tumor cell growth via TGFb signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:109–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fei P, Bernhard EJ, El-Deiry WS. Tissue-specific induction of p53 targets in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7316–7327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita T, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 1995;80:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, Nemoto J, Shibue T, Yamashita T, Tokino T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science. 2000;288:1053–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oda K, Arakawa H, Tanaka T, Matsuda K, Tanikawa C, Mori T, Nishimori H, Tamai K, Tokino T, Nakamura Y, et al. p53AIP1, a potential mediator of p53-dependent apoptosis, and its regulation by Ser-46-phosphorylated p53. Cell. 2000;102:849–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A model for p53-induced apoptosis [see comments] Nature. 1997;389:300–305. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y, Ma W, Benchimol S. Pidd, a new death-domain-containing protein, is induced by p53 and promotes apoptosis. Nat Genet. 2000;26:122–127. doi: 10.1038/79102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen-Schaub LB, Zhang W, Cusack JC, Angelo LS, Santee SM, Fujiwara T, Roth JA, Deisseroth AB, Zhang WW, Kruzel E, et al. Wild-type human p53 and a temperature-sensitive mutant induce Fas/APO-1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3032–3040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu GS, Burns TF, McDonald ER, III, Jiang W, Meng R, Krantz ID, Kao G, Gan DD, Zhou JY, Muschel R, et al. KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene [letter] Nat Genet. 1997;17:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman WH, Biade S, Zilfou JT, Chen J, Murphy M. Transcriptional repression of the anti-apoptotic survivin gene by wild type p53. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3247–3257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner H, Karnieli E, Rauscher FJ, LeRoith D. Wild-type and mutant p53 differentially regulate transcription of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8318–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Mehew JW, Heckman CA, Arcinas M, Boxer LM. Negative regulation of bcl-2 expression by p53 in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:240–251. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RA, Ince TA, Scotto KW. Transcriptional repression by p53 through direct binding to a novel DNA element. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27716–27720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Jiang P, Robinson M, Lawrence TS, Sun Y. AMPK-beta1 subunit is a p53-independent stress responsive protein that inhibits tumor cell growth upon forced expression. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:827–834. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fode C, Motro B, Yousefi S, Heffernan M, Dennis JW. Sak, a murine protein-serine/threonine kinase that is related to the Drosophila polo kinase and involved in cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6388–6392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fode C, Binkert C, Dennis JW. Constitutive expression of murine Sak-a suppresses cell growth and induces multinucleation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4665–4672. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson JW, Kozarova A, Cheung P, Macmillan JC, Swallow CJ, Cross JC, Dennis JW. Late mitotic failure in mice lacking Sak, a polo-like kinase. Curr Biol. 2001;11:441–446. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karn T, Holtrich U, Wolf G, Hock B, Strebhardt K, Rubsamen-Waicmann H. Human SAK related to the PLK/polo family of cell cycle kinases shows high mRNA expression in testis. Oncol Rep. 1997;4:505–510. doi: 10.3892/or.4.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pochampally R, Fodera B, Chen L, Lu W, Chen J. Activation of an MDM2-specific caspase by p53 in the absence of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15271–15277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Rea T, Bian J, Gray S, Sun Y. Identification of the genes responsive to etoposide-induced apoptosis: application of DNA chip technology. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Pommier Y, Colburn NH. Acquisition of a growth-inhibitory response to phorbol ester involves DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1907–1915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.el Deiry WS, Kern SE, Pietenpol JA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat Genet. 1992;1:45–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bian J, Jacobs C, Wang Y, Sun Y. Characterization of a putative p53 binding site in the promoter of the mouse tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3) gene: TIMP-3 is not a p53 target gene. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2559–2562. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.12.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bian J, Sun Y. p53CP, a putative p53 competing protein that specifically binds to the consensus p53 DNA binding sites: a third member of the p53 family? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14753–14758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaeser MD, Iggo RD. From the cover: Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis fails to support the latency model for regulation of p53 DNA binding activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:95–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012283399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng SY, Dai M-S, Keller DM, Lu H. SSRP1 functions as a co-activator of the transcriptional activator p63. EMBO J. 2002;21:5487–5497. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamashita Y, Kajigaya S, Yoshida K, Ueno S, Ota J, Ohmine K, Ueda M, Miyazato A, Ohya K, Kitamura T, et al. Sak serine-threonine kinase acts as an effector of Tec tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39012–39020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Tan M, Gosink M, Wang KK, Sun Y. Histone deacetylase 5 is not a p53 target gene, but its overexpression inhibits tumor cell growth and induces apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2913–2922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y, Bian J, Wang Y, Jacobs C. Activation of p53 transcriptional activity by 1,10-phenanthroline, a metal chelator and redox sensitive compound. Oncogene. 1997;14:385–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson M, Jiang P, Cui J, Li J, Wang Y, Swaroop M, Madore S, Lawrence TS, Sun Y. Global Genechip profiling to identify genes responsive to p53-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in human lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:406–415. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hudson JW, Chen L, Fode C, Binkert C, Dennis JW. Sak kinase gene structure and transcriptional regulation. Gene. 2000;241:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.el Deiry WS. Regulation of p53 downstream genes. Semin Cancer Biol. 1998;8:345–357. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farmer G, Friedlander P, Colgan J, Manley JL, Prives C. Transcriptional repression by p53 involves molecular interactions distinct from those with the TATA box binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4281–4288. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.21.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murphy M, Ahn J, Walker KK, Hoffman WH, Evans RM, Levine AJ, George DL. Transcriptional repression by wild-type p53 utilizes histone deacetylases, mediated by interaction with mSin3a. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2490–2501. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurova KV, Roklin OW, Krivokrysenko VI, Chumakov PM, Cohen MB, Feinstein E, Gudkov AV. Expression of prostate specific antigen (PSA) is negatively regulated by p53. Oncogene. 2002;21:153–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bian J, Sun Y. Transcriptional activation by p53 of the human type IV collagenase (gelatinase A or matrix metalloproteinase 2) promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6330–6338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee KC, Crowe AJ, Barton MC. p53-mediated repression of alpha-fetoprotein gene expression by specific DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1279–1288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B, Lee MY. Transcriptional regulation of the human DNA polymerase delta catalytic subunit gene POLD1 by p53 tumor suppressor and Sp1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29729–29739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manni I, Mazzaro G, Gurtner A, Mantovani R, Haugwitz U, Krause K, Engeland K, Sacchi A, Soddu S, Piaggio G. NF-Y mediates the transcriptional inhibition of the cyclin B1, cyclin B2, and cdc25C promoters upon induced G2 arrest. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5570–5576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yun J, Chae HD, Choy HE, Chung J, Yoo HS, Han MH, Shin DY. p53 negatively regulates cdc2 transcription via the CCAAT-binding NF-Y transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29677–29682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Modugno M, Tagliabue E, Ardini E, Berno V, Galmozzi E, De Bortoli M, Castronovo V, Menard S. p53-dependent downregulation of metastasis-associated laminin receptor. Oncogene. 2002;21:7478–7487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y, Sun Y, Wenger L, Rutter JL, Brinckerhoff CE, Cheung HS. p53 down-regulates human matrix metalloproteinase-1 (Collagenase-1) gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11535–11540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kubicka S, Kuhnel F, Zender L, Rudolph KL, Plumpe J, Manns M, Trautwein C. p53 represses CAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP)-dependent transcription of the albumin gene. A molecular mechanism involved in viral liver infection with implications for hepatocarcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32137–32144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Grand RJ, McCabe CJ, Franklyn JA, Gallimore PH, Turnell AS. Transcriptional regulation of the human glycoprotein hormone common alpha subunit gene by cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP)/p300 and p53. Biochem J. 2002;368:191–201. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai W, Wang Q, Traganos F. Polo-like kinases and centrosome regulation. Oncogene. 2002;21:6195–6200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donaldson MM, Tavares AA, Hagan IM, Nigg EA, Glover DM. The mitotic roles of Polo-like kinase. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2357–2358. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung GC, Hudson JW, Kozarova A, Davidson A, Dennis JW, Sicheri F. The Sak polo-box comprises a structural domain sufficient for mitotic subcellular localization. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nsb848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yuan J, Kramer A, Eckerdt F, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Efficient internalization of the polo-box of polo-like kinase 1 fused to an Antennapedia peptide results in inhibition of cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4186–4190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spankuch-Schmitt B, Wolf G, Solbach C, Loibl S, Knecht R, Stegmuller M, von Minckwitz G, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Downregulation of human polo-like kinase activity by antisense oligonucleotides induces growth inhibition in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3162–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masuda Y, Nishida A, Hori K, Hirabayashi T, Kajimoto S, Nakajo S, Kondo T, Asaka M, Nakaya K. Beta-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells by inhibiting the activity of a polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) Oncogene. 2003;22:1012–1023. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q, Xie S, Chen J, Fukasawa K, Naik U, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Dai W. Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by human Polo-like kinase 3 is mediated through perturbation of microtubule integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3450–3459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3450-3459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burns TF, Fei P, Scata KA, Dicker DT, El-Deiry WS. Silencing of the novel p53 target gene Snk/Plk2 leads to mitotic catastrophe in paclitaxel (taxol)-exposed cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5556–5571. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5556-5571.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kho PS, Wang Z, Zhuang L, Li Y, Chew JL, Ng HH, Liu ET, Yu Q. p53-regulated transcriptional program associated with genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21183–21192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ando K, Ozaki T, Yamamoto H, Furuya K, Hosoda M, Hayashi S, Fukuzawa M, Nakagawara A. Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) inhibits p53 function by physical interaction and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25549–25561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]