Abstract

VEGF121/rGel, a fusion protein composed of the growth factor VEGF121 and the recombinant toxin gelonin (rGel), targets the tumor neovasculature and exerts impressive cytotoxic effects by inhibiting protein synthesis. We evaluated the effect of VEGF121/rGel on the growth of metastatic MDA-MB-231 tumor cells in SCID mice. VEGF121/rGel treatment reduced surface lung tumor foci by 58% compared to controls (means were 22.4 and 53.3, respectively; P < .05) and the mean area of lung colonies by 50% (210 ± 37 m2 vs 415 ± 10 m2 for VEGF121/rGel and control, respectively; P < .01). In addition, the vascularity of metastatic foci was significantly reduced (198 ± 37 vs 388 ± 21 vessels/mm2 for treated and control, respectively). Approximately 62% of metastatic colonies from the VEGF121/rGel-treated group had fewer than 10 vessels per colony compared to 23% in the control group. The VEGF receptor Flk-1 was intensely detected on the metastatic vessels in the control but not in the VEGF121/rGel-treated group. Metastatic foci present in lungs had a three-fold lower Ki-67 labeling index compared to control tumors. Thus, the antitumor vascular-ablative effect of VEGF121/rGel may be utilized not only for treating primary tumors but also for inhibiting metastatic spread and vascularization of metastases.

Keywords: VEGF, gelonin, fusion toxin, vascular targeting, metastatic breast tumors

Introduction

Biologic studies examining the development of vascular tree in normal development and in disease states have identified numerous cytokines and their receptors that are responsible for triggering and maintaining this process [1–7]. Tumor neovascularization is not only central to the growth and development of the primary lesion, but appears to be a critical factor in the development and maintenance of metastases [8–12]. Clinical studies in bladder cancer [9] have demonstrated a correlation between microvessel density (MVD) and metastases. In addition, studies of breast cancer metastases by Aranda and Laforga [11] and Fox et al. [12] have demonstrated that microvessel count in primary tumors appears to be related to the presence of metastases in lymph nodes and micrometastases in bone marrow.

The cytokine vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and its receptors Flt-1/FLT-1 (VEGFR-1) and Flk-1/KDR (VEGFR-2) have been implicated as one of the central mediators of normal angiogenesis and tumor neovascularization [13–20]. Upregulation or overexpression of the KDR receptor or the VEGF-A ligand itself has been implicated as poor prognostic markers in various clinical studies of colon, breast, and pituitary cancers [21–23]. Recently, Padro et al. [24] have suggested that both VEGF-A and Flk-1/KDR may play a role in the neovascularization observed in bone marrow during acute myeloid leukemia tumor progression and may provide evidence that the VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway is important in leukemic growth.

For these reasons, there have been several groups interested in developing therapeutic agents and approaches targeting the VEGF-A pathway. Agents that prevent VEGF-A binding to its receptors, antibodies that directly block the Flk-1/KDR receptor, and small molecules that block the kinase activity of Flk-1/KDR, and thereby block growth factor signaling, are all under development [25–37]. Recently, our laboratory reported the development of a growth factor fusion construct of VEGF121 and the recombinant toxin gelonin (rGel) [38]. The rGel toxin is a single-chain N-glycosidase that is similar in its action to ricin-A chain [39]. Immunotoxins and fusion toxins containing rGel have been shown to specifically kill tumor cells in vitro and in vivo [40–43]. In currently ongoing clinical studies, gelonin does not appear to generate vascular leak syndrome (VLS) that limits the use of other toxins [44]. In addition, the development of hepatotoxicity commonly observed with toxin molecules has thus far not been observed for rGel-based agents. Our studies demonstrated that this agent was specifically cytotoxic only to cells expressing the KDR receptor and was not cytotoxic to cells overexpressing the FLT-1 receptor. In addition, this agent was shown to localize within the tumor vasculature and caused a significant damage to the vascular endothelium in both PC-3 prostate and A375 orthotopic xenograft tumor models.

There is now a significant body of evidence suggesting that breast tumor development, differentiation, and metastatic spread appear to be critically dependent on tumor neovascularization. Current studies suggest that the development of breast cancer primary tumors or metastatic sites > 2 mm are critically dependent on the growth of tumor neovasculature. We, therefore, evaluated the effect of VEGF121/rGel fusion toxin treatment on the growth of metastatic MDA-MB-231 tumor cells in SCID mice. Our data strongly suggest that the vascular-ablative effect of VEGF121/rGel may be used for inhibiting metastatic spread and the vascularization of metastases.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Bacterial strains, pET bacterial expression plasmids, and recombinant enterokinase were obtained from Novagen (Madison, WI). All other chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). TALON metal affinity resin was obtained from Clontech Laboratories (Palo Alto, CA). Other chromatography resins and materials were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS) from bovine neural tissue was obtained from Sigma. Murine brain endothelioma (bEnd.3) cells were provided by Professor Werner Risau (Max Plank Institute, Munich, Germany). Tissue culture reagents were from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD) or Mediatech Cellgro (Herndon, VA).

Antibodies

Rat antimouse CD31 antibody was from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit antigelonin antibody was produced in the Veterinary Medicine Core Facility at MDACC. The hybridoma producing the mouse monoclonal w6/32 antibody directed against human HLA antigen was purchased from ATCC. The w6/32 antibody was purified from hybridoma supernatant using protein A resin. MECA 32, a pan mouse endothelial cell antibody, was kindly provided by Dr. E. Butcher (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) and served as a positive control for immunohistochemical studies. The Ki-67 antibody was from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, UK). Antibodies to KDR and FLT-1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Goat antirat, antimouse, and antirabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP were purchased from Dako (Carpinteria, CA). Protein A/G agarose resin was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Cell Culture

Porcine aortic endothelial cells transfected with the KDR receptor (PAE/KDR) or the FLT-1 receptor (PAE/FLT-1) were a generous gift from Dr. J. Waltenberger. MDA-MB-231 cells were a generous gift from Dr. Janet Price. MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, PAE/KDR, and PAE/FLT-1 cells were maintained as a monolayer in F12 Nutrient Media (HAM) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum. SK-BR3 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum. BT474 cells were maintained in SK-BR3 media supplemented with 5 mg/ml insulin. Cells were harvested by treatment with Versene (0.02% EDTA) or trypsin-EDTA. Tumor cells intended for injection into mice were washed once and resuspended in serum-free medium without supplements. Cell number and viability were determined by staining with 0.2% trypan blue dye diluted in saline. Only single-cell suspensions of greater than 90% viability were used for in vivo studies.

Expression and Purification of VEGF121/rGel

The construction, expression, and purification of VEGF121/rGel have been previously described [38]. The fusion toxin was stored in sterile PBS at -20°C.

Cytotoxicity of VEGF121/rGel and rGel

The cytotoxicity of VEGF121/rGel and rGel against log phase PAE/KDR and PAE/FLT-1 cells has been previously described [38]. Here, we assessed the cytotoxicity of VEGF121/rGel and rGel against log phase human breast cancer cells and compared their cytotoxicity to PAE/KDR cells. Cells were grown in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates. Purified VEGF121/rGel and rGel were diluted in culture media and added to the wells in five-fold serial dilutions. Cells were incubated for 72 hours. The remaining adherent cells were stained with crystal violet (0.5% in 20% methanol) and solubilized with Sorenson's buffer (0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 4.2 in 50% ethanol). Absorbance was measured at 630 nm.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell extracts were obtained by lysing cells in cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 M KCl, and 20% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors [leupeptin (0.5%), aprotinin (0.5%), and PMSF (0.1%)]. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and electrophoretically transferred to a PVDF membrane overnight at 4°C in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 190 mM glycine, and 20% HPLC-grade methanol). The samples were analyzed for KDR with rabbit anti-KDR polyclonal antibody and FLT-1 using an anti-FLT-1 polyclonal antibody. The membranes were then incubated with goat antirabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP), developed using the ECL detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and exposed to X-ray film.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed as described above. Five hundred micrograms of whole cell lysates of MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, BT474, and SK-BR3 cells was mixed with 2 µg of anti-KDR or anti-FLT-1 polyclonal antibodies in a final volume of 250 ml and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. One hundred micrograms of PAE/KDR and PAE/FLT-1 cell lysates was immunoprecipitated as controls. The mixtures were then incubated for 2 hours with Protein A/G agarose beads that had been blocked with 5% BSA. The beads were washed four times in lysis buffer and the samples, along with 30 µg of PAE/KDR cell lysate, were run on a gel, transferred overnight onto a PVDF membrane, and probed using anti-KDR or anti-FLT-1 antibodies.

Isolation of RNA and Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and its integrity was verified by electrophoresis on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel. RT-PCR analysis was performed using the following primers: KDR forward—5′ ATTACTTGCAGGGGACAG; KDR reverse—5′ GGAACAAATCTCTTTTCTGG; FLT-1 forward—5′ CAAATGCAACGTACAAAGA; FLT-1 reverse—5′ AGAGTGGCAGTGAGGTTTTT; GAPDH forward—5′GTCGTCTTCACCACCATGGAG; and GAPDH reverse—5′ CCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGC. Isolated RNA was subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis as described by the manufacturer of the Superscript First Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RT-PCR was performed using a Minicycler PCR machine (MJ Research, Inc., San Francisco, CA).

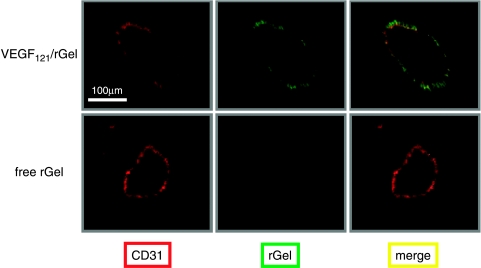

Localization of VEGF121/rGel to Blood Vessels of MDA-MB-231 Lung Metastatic Foci

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines and protocols. Tumor cells (5 x 105 per mouse) were injected intravenously (i.v.) and, 4 to 5 weeks later, the mice began to show signs of respiratory distress. At this time, the mice were injected i.v. with VEGF121/rGel (50 µg/mouse) or free rGel (20 µg/mouse, molar equivalent to VEGF121/rGel). One hour later, the mice were sacrificed and exsanguinated. All major organs and tumor were harvested and snap-frozen for the preparation of cryosections. Frozen sections were double-stained with anti-CD-31 (5 µg/ml) followed by detection of the localized fusion protein using rabbit antigelonin antibody (10 µg/ml). CD-31 rat IgG was visualized by goat antirat IgG conjugated to Cy-3 (red fluorescence). Rabbit antigelonin antibody was detected by goat antirabbit IgG conjugated to FITC (green fluorescence). Colocalization of both markers was indicated by the yellow color. Anti-rGel antibody had no reactivity with tissues sections derived from mice injected with saline or with VEGF121.

Metastatic Model of MDA-MB-231 Tumors

A maximum tolerated dose of 45 mg/kg for VEGF121/rGel under the conditions described below was established. For treatment purposes, 70% of the MTD was used. We currently demonstrate a comparison with a diluent (saline) control as previous studies have demonstrated no impact of free rGel on the growth of tumor xenografts [38]. Female SCID mice, aged 4 to 5 weeks, were injected in a tail vein with 0.1 ml of MDA-MB-231 cell suspension (5 x 105 cells). The mice were randomly separated into two groups (six mice per group) and were treated with either VEGF121/rGel or rGel starting on the eighth day after the injection of cells. VEGF121/rGel was delivered at 100 µg/dose intraperitoneally, for a total of six times, with the interval of 3 days. The molar equivalent of rGel (40 µg) was delivered at the same schedule. Intraperitoneal, rather than intravenous, injection was chosen solely to prevent necrosis of the tail vein due to repeated injections. Animal weight was monitored. Three weeks after termination of the treatment, the animals were sacrificed and their lungs were removed. One lobe was fixed in Bouin's fixative and the other lobe was snap-frozen. After fixation in Bouin's fixative, the tumor colonies on the lung surface appeared white, whereas the normal lung tissue appeared brown. The number of tumor colonies on the surface of each lung was counted and the weight of each lung was measured. The values obtained from individual mice in the VEGF121/rGel and rGel groups were averaged per group.

Determination of the Number, Size, and Vascular Density of Lung Metastatic Foci

Frozen samples of lung tissue were cut to produce sections of 6 µm. Blood vessels were visualized by MECA 32 antibody and metastatic lesions were identified by morphology and w6/32 antibody, directed against human HLA antigens. Each section was also double-stained by MECA 32 and w6/32 antibodies to ensure that the analyzed blood vessels are located within a metastatic lesion. Slides were first viewed at low magnification (x2 objective) to determine the total number of foci per cross section. Six slides derived from individual mice in each group were analyzed and the number was averaged. Images of each colony were taken using a digital camera (CoolSnap) at magnifications of x40 and x100, and analyzed using Metaview software, which allows measurements of the smallest and largest diameter, perimeter (µm), and area (mm2). The vascular endothelial structures identified within a lesion were counted and the number of vessels per each lesion was determined and normalized per square millimeter. The mean number of vessels per square millimeter was calculated per slide and averaged per VEGF121/rGel and rGel groups (six slides per group). The results are expressed as ±SEM. The same method was applied to determine the mean number of vessels in nonmalignant tissues.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of Proliferation of Tumor Cells in Lung Colonies

Frozen sections of mouse normal organs and metastatic lungs were fixed with acetone for 5 minutes and rehydrated with PBS-T for 10 minutes. All dilutions of antibodies were prepared in PBS-T containing 0.2% BSA. Primary antibodies were detected by appropriate antimouse, antirat, or antirabbit HRP conjugates. HRP activity was detected by developing with DAB substrate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To determine number of cycling cells, sections were stained with the Ki-67 antibody followed by antimouse IgG HRP conjugate. Sections were analyzed at a magnification of x100. The number of cells positive for Ki-67 was normalized per square millimeter. The mean ± SD per VEGF121/rGel and control group is presented. The average numbers derived from analysis of each slide were combined per either VEGF121/rGel or rGel group and analyzed for statistical differences.

Expression of Flk-1 in Metastatic Lung Tumors

The expression of Flk-1 on the vasculature of breast tumors metastatic to the lungs was also assessed using the RAFL-1 antibody as described by Ran et al. [45]. Frozen sections of lungs from mice treated with VEGF121/rGel or free gelonin stained with monoclonal rat antimouse VEGFR-2 antibody RAFL-1 (10 µg/ml). RAFL-1 antibody was detected by goat antirat IgG HRP.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined by oneway analysis of variance followed by the Student's t test.

Results

Expression of KDR and FLT-1 RNA and Protein in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

Because VEGF121 binds only to KDR and FLT-1, we first examined RNA and protein levels of these two receptors in several breast cancer cell lines: BT474, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, and SK-BR3. Total RNA was harvested from log phase cells, analyzed for integrity, and subjected to RT-PCR with primers KDR, FLT-1, and GAPDH (control). KDR and FLT-1 were immunoprecipitated from whole cell extracts and identified by Western blot analysis. PAE/KDR and PAE/FLT-1 cells were used as positive controls. None of the breast cancer cell lines expressed detectable levels of FLT-1 RNA or protein as determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis (data summarized in Table 1). RT-PCR analysis of MDA-MB-231 showed extremely low levels of KDR compared to PAE/KDR. However, MDA-MB-231 cells did not express detectable amounts of KDR protein. The other breast cell lines did not express detectable amounts of KDR RNA or protein.

Table 1.

Correlation between the Presence of VEGF121 Receptors and Sensitivity to VEGF121/rGel.

| Cell Type | RT-PCR | Immunoprecipitation | IC50 (nM) | Targeting Index* | |||

| KDR | FLT-1 | KDR | FLT-1 | VEGF121/rGel | rGel | ||

| BT474 | - | - | - | - | 300 | 2000 | 7 |

| MDA-MB-231 | + | - | - | - | 150 | 40 | 0.3 |

| MDA-MB-435 | - | - | - | - | 56 | 327 | 6 |

| SK-BR3 | - | - | - | - | 200 | 500 | 2.5 |

Targeting index is defined as (IC50 rGel)/(IC50 VEGF121/rGel).

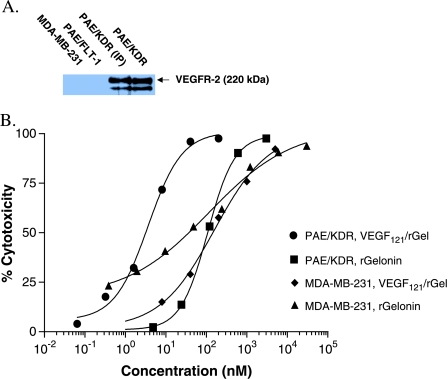

Cytotoxicity of VEGF121/rGel on MDA-MB-231 Cells

We have previously demonstrated that VEGF121/rGel is cytotoxic to endothelial cells expressing KDR but not FLT-1 [38]. As assessed by Western blot, none of the breast cancer cell lines examined appears to express FLT-1 or KDR—the receptors that bind VEGF121. We additionally examined the cytotoxicity of VEGF121/rGel and rGel on these breast cancer cell lines. BT474, MDA-MB-435, and SK-BR3 all show a slightly lower IC50 for VEGF121/rGel compared to rGel alone. In contrast, MDA-MB-231 cells in culture showed an IC50 slightly higher than that observed for recombinant gelonin (Table 1 and Figure 1), indicating that VEGF121/rGel does not have a specific target on MBA-MB-231 cells. The IC50 of untargeted rGel toward MDA-MB-231 cells is similar to its IC50 toward PAE/KDR cells (Figure 1). Compared to the IC50 of VEGF121/rGel toward PAE/KDR cells (1 nM), the IC50 of VEGF121/rGel toward the breast cancer cell lines examined was much higher, ranging from 30 to 300 nM. Indeed, the IC50 of VEGF121/rGel toward these breast cancer cell lines was in the IC50 range of untargeted rGel toward the PAE/KDR cells. Taken together, these in vitro data suggest that MDA-MB-231 tumor cells are not specifically targeted by VEGF121/rGel, and that any in vivo effect on the growth of tumors would be due to VEGF121/rGel targeting the tumor vasculature rather than the tumor cells themselves.

Figure 1.

MDA-MB-231 cells are not targeted by VEGF121/rGel due to the lack of expression of VEGFR-2/KDR. (A) Western analysis demonstrating the presence of KDR on endothelial cells transfected with the KDR receptor (PAE/KDR) but not on cells expressing the FLT-1 receptor (PAE/FLT-1, negative control). As shown, the MDA-MB-231 cells did not express detectable amounts of KDR. (B) Log phase MDA-MB-231 and PAE/KDR cells were treated with various doses of VEGF121/rGel or rGel for 72 hours. VEGF121/rGel was far more toxic than rGel toward PAE/KDR cells (IC50 of 1 vs 100 nM). In contrast, the cytotoxic effects of both agents were similar toward MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50 of 150 nM with VEGF121/rGel vs 40 nM with rGel), demonstrating no specific cytotoxicity of the fusion construct compared to free toxin on these cells.

Localization of VEGF121/rGel to the Vasculature of MDA-MB-231 Lung Metastatic Foci

Mice bearing metastatic MDA-MB-231 tumors were injected intravenously with either VEGF121/rGel or free rGel and, 1 hour later, the mice were exsanguinated. Frozen sections were prepared from the lung tumor foci and normal organs, and examined immunohistochemically to determine the location of the free rGel and the gelonin fusion construct. VEGF121/rGel was primarily detected on the endothelium of tumor (Figure 2). Vessels with bound VEGF121/rGel were homogeneously distributed within the tumor vasculature. No VEGF121/rGel staining was detected in any of the normal tissues examined (lung, liver, kidney, heart, spleen, pancreas, and brain; data not shown). Free rGel did not localize to tumor or normal vessels in any of the mice, indicating that only targeted rGel was able to bind to the tumor endothelium. These results indicate that VEGF121/rGel specifically localizes to tumor vessels, which demonstrate a high density and a favorable distribution of the VEGF121/rGel-binding sites.

Figure 2.

VEGF121/rGel localizes to the vasculature of breast tumor foci in the lungs of mice. Female SCID mice were injected i.v. with 0.1 ml of MDA-MB-231 cell suspension (5 x 105 cells) as described in the Materials and Methods section. Six weeks later, mice were administered one dose (i.v., tail vein) of 100 µg of VEGF121/rGel. Four hours later, the mice were sacrificed and the tumor-bearing lungs were fixed. Tissue sections were stained for blood vessels using the anti-CD-31 antibody (red) and the section was counterstained using an antigelonin antibody (green). Colocalization of the stains (yellow) demonstrates the presence of the VEGF121/rGel fusion construct specifically in blood vessels and not on tumor cells.

MDA-MB-231 Model of Experimental Pulmonary Metastases and Rationale for Therapeutic Regimen

Human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells consistently lodge in lungs following intravenous injection into the tail vein of athymic or SCID mice. Micrometastases are first detected 3 to 7 days after injection of 5 x 105 cells, and macroscopic colonies develop in 100% of the injected mice within 4 to 7 weeks. Mortality occurs in all mice within 10 to 15 weeks. This model of experimental breast cancer metastasis examines the ability of tumor cells to survive in the blood circulation, extravasate through the pulmonary vasculature, and establish growing colonies in the lung parenchyma.

We evaluated the effect of VEGF121/rGel on the growth and survival of the established micrometastases. We, therefore, started the treatment 8 days after injection of the tumor cells. By that time, based on our prior observations, tumor cells that were able to survive in the circulation and traverse the lung endothelial barrier are localized within the lung parenchyma and initiate tumor angiogenesis. Treatment with VEGF121/rGel was given intraperitoneally for the following 3 weeks as described under the Materials and Methods section, with the mice receiving 70% of the maximum tolerated accumulative dose of the drug (900 µg/mouse). Prior studies established that the VEGF121/rGel given at such dose did not cause histopathologic changes in normal organs. The accumulative dose of total VEGF121/rGel fusion protein did not induce significant toxicity as judged by animal behavior morphologic evaluation of normal organs. Transient loss of weight (∼10%) was observed 24 hours after most of the treatments with complete weight recovery thereafter. Colonies were allowed to expand in the absence of treatment for the following 3 weeks to evaluate the long-term effect of VEGF121/rGel on the size of the colonies, proliferation index of tumor cells, and their ability to induce new blood vessel formation.

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on the Number and Size of MDA-MB-231 Tumor Lesions in Lungs

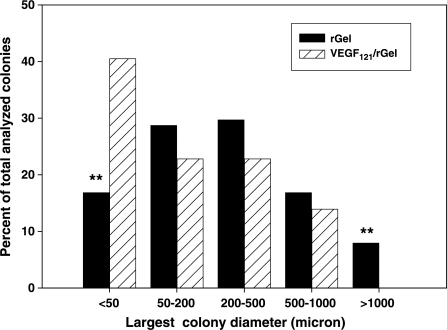

An antibody directed against human HLA was used to identify metastatic lesions of MDA-MB-231 cells on samples of lung tissue. Treatment with VEGF121/rGel, but not with free rGel, significantly reduced by between 42% and 58% both the number of colonies per lung and the size of the metastatic foci present in the lung, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 2.

Figure 3.

VEGF121/rGel reduces number of large colonies in the metastatic lungs. The size of tumor colonies was analyzed on slides stained with w6/32 antibody, which specifically recognizes human HLA antigens. The antibody delineates colonies of human tumor cells and defines borders between metastatic lesions and mouse lung parenchyma. The largest size differences between VEGF121/rGel and control groups were found in groups of colonies having diameters either less than 50 µm or more than 1000 µm. In the VEGF121/rGel-treated mice, more than 40% of total foci was extremely small (<50 µm) compared to 18% in the control group. The control mice had approximately 8% of the extremely large colonies (>1000 µm), whereas VEGF121/rGel-treated mice did not have colonies of this size.

Table 2.

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on the Number and Size of Pulmonary Metastases of MDA-MB-231 Human Breast Carcinoma Cells.

| Parameter | Treatment* | % Inhibition versus rGel Treatment | P value† | |

| rGel | VEGF121/rGel | |||

| Number of surface colonies per lung (range)‡ | 53.3 ± 22 (33–80) | 22.4 ± 9.2 (11–41) | 58.0 | 0.03 |

| Number of intraparenchymal colonies per cross section (range)§ | 22 ± 7.5 (18–28) | 12.8 ± 5.5 (5–18) | 42.0 | 0.02 |

| Mean area of colonies (µm)¶ | 415 ± 10 | 201 ± 37 | 51.9 | 0.01 |

| Mean % of colony-occupied area per lung section# | 57.3 ± 19 | 25.6 ± 10.5 | 55.4 | 0.01 |

Mice with MDA-MB-231 pulmonary micrometastases were treated intraperitoneally with VEGF121/rGel or free gelonin as described under Materials and Methods and Results sections.

P value was calculated using Student's t test.

Lungs were fixed with Bouin's fixative for 24 hours. The number of surface white colonies was determined for each sample and averaged among six mice from VEGF121/rGel or rGel control group. Mean number per group ±SEM is shown. Numbers in parentheses represent the range of colonies in each group.

Frozen sections were prepared from metastatic lungs. Sections were stained with 6w/32 antibody recognizing human tumor cells. The number of intraparenchymal colonies identified by brown color was determined for each cross section and averaged among six samples of individual mice from VEGF121/rGel or rGel control group. The mean number per group ±SEM is shown. Numbers in parentheses represent the range of colonies in each group.

The area of foci identified by 6w/32 antibody was measured by using Metaview software. The total number of evaluated colonies was 101 and 79 for rGel and VEGF121/rGel group, respectively. Six individual slides per group were analyzed. The mean area of colony in each group ±SEM is shown.

The sum of all regions occupied by tumor cells and the total area of each lung cross section were determined and the percentage of metastatic regions from total was calculated. The values obtained from each slide were averaged among six samples from VEGF121/rGel or rGel control group. The mean percent area occupied by metastases from the total area per group ±SEM is shown.

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on the Vascularity of MDA-MB-231 Pulmonary Metastatic Foci

Blood vessels were visualized by MECA 32 antibody. The overall mean vascular density of lung colonies was reduced by 51% compared to the rGel-treated controls (Table 3 and Figure 4); however, the observed effect was nonuniformly distributed by tumor colony size. The greatest impact on vascularization was observed on mid-sized and extremely small tumors (62% and 69% inhibition, respectively), whereas large tumors demonstrated the least effect (10% inhibition). The majority of lesions in the VEGF121/rGel-treated mice (∼70%) was avascular, whereas only 40% of lesions from the control group did not have vessels within the metastatic lung foci.

Table 3.

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on the Vascularity of Pulmonary Metastases of MDA-MB-231 Human Breast Carcinoma Cells.

| Size of Colonies | Largest Diameter Range (µm) | Number of Vascularized Colonies from Total Inhibition Analyzed (%)* | % Inhibition versus Radiation Treatment | ||

| Group† | Description | rGel | VEGF121/rGel | ||

| A | Extremely small | <50 | 7/24 (29%) | 3/32 (9.3%) | 69 |

| B | Small | 50–200 | 19/48 (39.5%) | 6/24 (25%) | 37 |

| C | Mid-sized | 200–500 | 25/30 (83.3%) | 8/25 (32%) | 62 |

| D | Large | 500–1000 | 17/17 (100%) | 10/11 (90.0%) | 10 |

| E | Extremely large | >1000 | 8/8 (100%) | N/A | N/A |

| Number of vascular foci/total analyzed (%)‡ | 76/127 (59.8%) | 27/92 (29.3%) | 51 | ||

Frozen lung sections from VEGF121/rGel and rGel-treated mice were stained with MECA 32 antibody. A colony was defined as vascularized if at least one blood vessel branched out from the periphery and reached a center of the lesion. Six slides per group derived from individual mice were analyzed and data were combined.

Colonies identified on each slide of a metastatic lung were subdivided into five groups (A–E) according to their largest diameter.

The total number of the analyzed colonies was 127 and 92 for rGel- and VEGF121/rGel-treated groups, respectively. Seventy percent of foci in the VEGF121/rGel-treated group was a vascular, whereas only 40% of lesions from the control group did not have vessels within the metastatic foci.

Figure 4.

VEGF121/rGel inhibits the vascularization of MDA-MB-231 pulmonary metastases. (A) Lungs derived from VEGF121/rGel and rGel-treated mice were stained with MECA 32 antibody and the vascular density within the metastatic foci was determined. The mean number of vessels per square millimeter in lung metastases of VEGF121/rGel-treated mice was reduced by approximately 50% compared to those in rGel-treated mice. (B) Representative images demonstrating reduction of vascular density in foci of comparable size in mice treated with rGel (left) and VEGF121/rGel fusion protein (right).

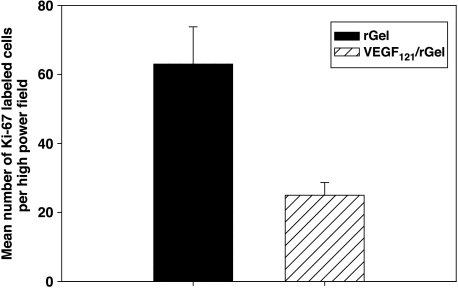

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on the Number of Cycling Cells in the Metastatic Foci

The growth rate of MDA-MB-231 cells was determined by staining cells with Ki-67 antibody, as described. The number of cycling tumor cells in lesions from the VEGF121/rGel group was also reduced by ∼60% compared to controls (Figure 5). This finding suggests that the vascularity of metastases directly affects tumor cell proliferation.

Figure 5.

VEGF121/rGel inhibits the proliferation of metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells in the lungs. Frozen sections of lungs derived from VEGF121/rGel and rGel-treated mice were stained with Ki-67 antibody. Stained sections were examined under x40 objective to determine the number of tumor cells with positive nuclei (cycling cells). Positive cells were enumerated in 10 colonies per slide on six sections derived from individual mice per treatment group. The mean number per group ±SEM is presented. VEGF121/rGel treatment reduced the average number of cycling cells within the metastatic foci by approximately 60%.

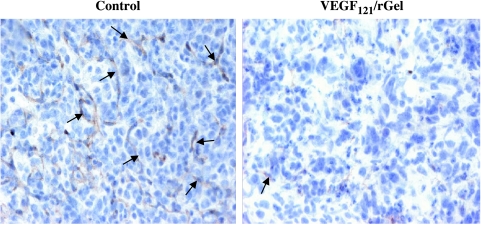

Effect of VEGF121/rGel on Flk-1 Expression in Tumor Vessel Endothelium

The expression of Flk-1 on the remaining few vessels present in lung metastatic foci demonstrated a significant decline compared to that of lung foci present in control tumors (Figure 6). This suggests that the VEGF121/rGel agent is able to significantly downregulate the receptor or prevent the outgrowth of highly receptor-positive endothelial cells.

Figure 6.

Detection of Flk-1/VEGFR-2 on the vasculature of metastatic lesions by the anti-VEGFR-2 antibody, RAFL-1. Frozen sections of lungs from mice treated with VEGF121/rGel or free gelonin stained with monoclonal rat antimouse VEGFR-2 antibody RAFL-1 (10 µg/ml). RAFL-1 antibody was detected by goat antirat IgG HRP, as described under the Materials and Methods section. Sections were developed with DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin. Representative images of lung metastases of comparable size (700–800 µm in the largest diameter) from each treatment group are shown. Images were taken with an objective of x20. Note that the pulmonary metastases from the VEGF121/rGel-treated group show both reduced vessel density and decreased intensity of anti-VEGFR-2 staining compared to control lesions.

Discussion

Neovascularization is a particularly important hallmark of breast tumor growth and metastatic spread [46–50]. The growth factor VEGF-A and the receptor KDR have both been implicated in highly metastatic breast cancers [51–53]. We have previously demonstrated that the VEGF121/rGel growth factor fusion toxin specifically targets Flk-1/KDR-expressing tumor vascular endothelial cells and inhibits the growth of subcutaneously implanted human tumor xenografts [38]. The current study was designed to evaluate its effect on the development of breast cancer metastases in lungs following intravenous injection of MDA-MB-231 cells.

The salient finding of our study of the VEGF121/rGel construct is that: this fusion toxin is specifically cytotoxic to cells overexpressing the KDR receptor for VEGF. However, the human breast MDA-MB-231 cells employed for these studies do not express this receptor and, therefore, were not directly affected by this agent (Figure 1). Although the antitumor effects of VEGF121/rGel observed from our in vivo studies appear to be solely the result of targeting the Flk-1-expressing tumor vasculature and not the tumor cells themselves, one cannot rule out a direct effect on tumor cells or a combination of targeting both the tumor and the vasculature. Administration of the VEGF121/rGel construct to mice previously injected (i.v.) with tumor cells dramatically reduced the number of tumor colonies found in the lung, their size, and their vascularity. In addition, the number of cycling breast tumor cells within lung metastatic foci was found to be reduced by an average of 60%. This reduction compares favorably to the effect of DT-VEGF on the growth of pancreatic cancer [54] and to other vascular targeting agents such as Avastin, which had an overall clinical response rate of 9.3% in a Phase I/II dose escalation trial in previously treated metastatic breast cancers [55]. In addition to the reduced number of blood vessels present in lung metastases of treated mice, we also found that the few vessels present had a greatly reduced expression of VEGFR-2. Therefore, this construct demonstrated an impressive long-term impact on the growth and development of breast tumor metastatic foci found in the lungs.

Targeting tumor vasculature with a variety of technologies has been shown to inhibit the growth and development of primary tumors as well as metastases. Recently, Shaheen et al. [56] demonstrated that small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors active against the receptors for VEGF, fibroblast growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factors were also capable of inhibiting microvessel formation and metastases in tumor model systems. Previously, Seon et al. [57] demonstrated long-term antitumor effects of an antiendoglin antibody conjugated with ricin-A chain (RTA) in a human breast tumor xenograft model.

Surprisingly, one finding from our study was that administration of VEGF121/rGel resulted in a three-fold decrease in the number of Ki-67-labeled (cycling) cells in the metastatic foci present in the lung (Figure 5). Clinical studies have suggested that tumor cell cycling may be an important prognostic marker for disease-free survival in metastatic breast cancer, but that Ki-67 labeling index, tumor MVD, and neovascularization appear to be independently regulated processes [58,59]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a significant reduction in tumor labeling index produced by a vascular targeting agent.

Another critical finding from our studies is the observation that the vascular-ablative effects of the VEGF121/rGel fusion construct alone were unable to completely eradicate lung metastases. Although the growth of larger pulmonary metastases was completely inhibited by this therapeutic approach, the development of small, avascular, metastatic foci within lung tissues was observed. Our findings indicate that vasculature in the small and mid-sized metastatic lesions (diameter < 500 µm) was much more susceptible to the action of VEGF121/rGel than that in colonies with diameters larger than 500 µm. Several explanations might account for this observation. First, the number of VEGF receptors on endothelial cells within the small, exponentially expanding colonies might be higher than that in the well-established lesions. This would lead to an increase in binding sites for VEGF121/rGel and, hence, an increased toxicity toward vessels specifically in small colonies. Second, vascular endothelial cells in small colonies might have a reduced capacity to survive after drug assault compared to vessels in established lesions. This could be due to insufficient recruitment of supporting cells (pericytes/smooth muscle cells) to the newly formed vessels, and/or derangements in the production of and interaction with components of basement membrane. Currently, the precise mechanism of the differential anti-vascular toxicity on different size colonies is not completely understood. However, these data strongly suggest that the combination of vascular targeting agents with chemotherapeutic agents or with radiotherapeutic agents, which directly damage tumor cells themselves, may provide for greater therapeutic effect. Studies of several vascular targeting agents in combination with chemotherapeutic agents have already demonstrated a distinct in vivo antitumor advantage of this combination modality against experimental tumors in mice [60]. Studies by Pedley et al. [61] have also suggested that the combination of vascular targeting and radioimmunotherapy may also present a potent antitumor combination. Finally, studies combining hyperthermia and radiotherapy with vascular targeting agents have demonstrated an enhanced activity against mammary carcinoma tumors in mice [62]. Studies in our laboratory combining VEGF121/rGel and various chemotherapeutic agents, biologic agents, or therapeutic agents targeting tumor cells are currently ongoing.

The rGel toxin is a single-chain N-glycosidase that is similar in its action to ricin-A chain [39]. However, unlike ricin-A chain, the use of rGel does not appear to result in VLS [44]. Side effects have been observed with clinical administration of RTA-based, diphtheria toxin-based, and Pseudomonas exotoxin-based fusion proteins. These side effects include liver toxicity, development of neutralizing antibodies, and development of VLS. The development of neutralizing antibodies was found in 69% of patients treated with RTA immunotoxins [63], 37% of patients treated with PE-based constructs [64], and 92% of patients treated with DT constructs [65]. In contrast, our ongoing clinical trial with an rGel-based conjugate currently demonstrates a relatively low antigenicity of the rGel component, with only 2 of 22 patients developing antibodies to the rGel portion of the drug [44]. In addition, the development of hepatoxicity and VLS is commonly observed, with toxin molecules thus far not having been observed for rGel-based agents. These findings support continuing development in a clinical setting of targeted therapy using rGel. In addition, our laboratory continues to develop designer toxins with reduced antigenicity and size [66].

The presented findings demonstrate that VEGF121/rGel can clearly and specifically target Flk-1/KDR-expressing tumor vasculature both in vitro and in vivo and that this agent can have an impressive inhibitory effect on tumor metastases. Studies are continuing in our laboratory to examine the activity of this agent alone and in combination against a variety of orthotopic and metastatic tumor models.

Abbreviations

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficient

- VEGF, VEGF-A

vascular endothelial growth factor-A

- Flt-1, FLT-1, VEGFR-1

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1

- Flk-1, KDR, VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

- rGel

gelonin

- i.v.

intravenous

Footnotes

This research was supported, in part, by the following: Clayton Foundation for Research, Department of Defense (DAMD-17-02-1-0457), and the Gillson-Longenbaugh Foundation.

References

- 1.Birnbaum D. VEGF-FLT1 receptor system: a new ligand-receptor system involved in normal and tumor angiogenesis. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86 (inside cover) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis: past, present and the near future. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:505–515. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bando H, Toi M. Tumor angiogenesis, macrophages, and cytokines. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;476:267–284. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4221-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falterman KW, Ausprunk H, Klein MD. Role of tumor angiogenesis factor in maintenance of tumor-induced vessels. Surg Forum. 1976;27:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patt LM, Houck JC. Role of polypeptide growth factors in normal and abnormal growth. Kidney Int. 1983;23:603–610. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, Dillehay LE, Madan A, Semenza GL, Bedi L. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:34–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman J. Proceedings: tumor angiogenesis factor. Cancer Res. 1974;34:2109–2113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strugar J, Rothbart D, Harrington W, Criscuolo GR. Vascular permeability factor in brain metastases: correlation with vasogenic brain edema and tumor angiogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:560–566. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.4.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeger TM, Weidner N, Chew K, Moore DH, Kerschmann RL, Waldman FM, Carroll PR. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with lymph node metastases in invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 1995;154:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melnyk O, Zimmerman M, Kim KJ, Shuman M. Neutralizing anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody inhibits further growth of established prostate cancer and metastases in a pre-clinical model. J Urol. 1999;161:960–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aranda FI, Laforga JB. Microvessel quantitation in breast ductal invasive carcinoma. Correlation with proliferative activity, hormonal receptors and lymph node metastases. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:124–129. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox SB, Leek RD, Bliss J, Mansi JL, Gusterson B, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Association of tumor angiogenesis with bone marrow micrometastases in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1044–1049. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.14.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senger DR, Van de Water L, Brown LF, Nagy JA, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Berse B, Jackman RW, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor (VPF, VEGF) in tumor biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1993;12:303–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00665960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon G. VEGF receptor signaling in tumor angiogenesis. Oncologist. 2000;5(Suppl 1):3–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-suppl_1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obermair A, Kucera E, Mayerhofer K, Speiser P, Seifert M, Czerwenka K, Kaider A, Leodolter S, Kainz C, Zeillinger R. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human breast cancer: correlation with disease-free survival. Int J Cancer. 74:455–458. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970822)74:4<455::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-8. (199) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyoshi C, Ohshima N. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression regulates angiogenesis accompanying tumor growth in a peritoneal disseminated tumor model. In Vivo. 2001;15:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibuya M. Role of VEGF-flt receptor system in normal and tumor angiogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 1995;67:281–316. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60716-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detmar M. The role of VEGF and thrombospondins in skin angiogenesis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(Suppl 1):S78–S84. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(00)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verheul HM, Pinedo HM. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in tumor angiogenesis and early clinical development of VEGF-receptor kinase inhibitors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2000;1(Suppl 1):S80–S84. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2000.s.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe CJ, Boelaert K, Tannahill LA, Heaney AP, Stratford AL, Khaira JS, Hussain S, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA, Gittoes NJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor, its receptor KDR/Flk-1, and pituitary tumor transforming gene in pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4238–4244. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kranz A, Mattfeldt T, Waltenberger J. Molecular mediators of tumor angiogenesis: enhanced expression and activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR in primary breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:293–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990621)84:3<293::aid-ijc16>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harada Y, Ogata Y, Shirouzu K. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor KDR (kinase domain-containing receptor)/Flk-1 (fetal liver kinase-1) as prognostic factors in human colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6:221–228. doi: 10.1007/pl00012109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padro T, Bieker R, Ruiz S, Steins M, Retzlaff S, Burger H, Buchner T, Kessler T, Herrera F, Kienast J, et al. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its cellular receptor KDR (VEGFR-2) in the bone marrow of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2002;16:1302–1310. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedge SR, Ogilvie DJ, Dukes M, Kendrew J, Curwen JO, Hennequin LF, Thomas AP, Stokes ES, Curry B, Richmond GH, et al. ZD4190: an orally active inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling with broad-spectrum antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laird AD, Vajkoczy P, Shawver LK, Thurnher A, Liang C, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger M, Ullrich A, Hubbard SR, Blake RA, et al. SU6668 is a potent antiangiogenic and antitumor agent that induces regression of established tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4152–4160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haluska P, Adjei AA. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2001;2:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabbro D, Ruetz S, Bodis S, Pruschy M, Csermak K, Man A, Campochiaro P, Wood J, O'Reilly T, Meyer T. PKC412—a protein kinase inhibitor with a broad therapeutic potential. Anticancer Drug Des. 2000;15:17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabbro D, Buchdunger E, Wood J, Mestan J, Hofmann F, Ferrari S, Mett H, O'Reilly T, Meyer T. Inhibitors of protein kinases: CGP 41251, a protein kinase inhibitor with potential as an anticancer agent. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;82:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun L, McMahon G. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by synthetic receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2000;5:344–353. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solorzano CC, Baker CH, Bruns CJ, Killion JJ, Ellis LM, Wood J, Fidler IJ. Inhibition of growth and metastasis of human pancreatic cancer growing in nude mice by PTK 787/ZK222584, an inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2001;16:359–370. doi: 10.1089/108497801753354267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drevs J, Hofmann I, Hugenschmidt H, Wittig C, Madjar H, Muller M, Wood J, Martiny-Baron G, Unger C, Marme D. Effects of PTK787/ZK 222584, a specific inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, on primary tumor, metastasis, vessel density, and blood flow in a murine renal cell carcinoma model. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4819–4824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimitroff CJ, Klohs W, Sharma A, Pera P, Driscoll D, Veith J, Steinkampf R, Schroeder M, Klutchko S, Sumlin A, et al. Anti-angiogenic activity of selected receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, PD166285 and PD173074: implications for combination treatment with photodynamic therapy. Invest New Drugs. 1999;17:121–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1006367032156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendel DB, Schreck RE, West DC, Li G, Strawn LM, Tanciongco SS, Vasile S, Shawver LK, Cherrington JM. The angiogenesis inhibitor SU5416 has long-lasting effects on vascular endothelial growth factor receptor phosphorylation and function. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4848–4858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prewett M, Huber J, Li Y, Santiago A, O'Connor W, King K, Overholser J, Hooper A, Pytowski B, Witte L, et al. Antivascular endothelial growth factor receptor (fetal liver kinase 1) monoclonal antibody inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth of several mouse and human tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5209–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Wiesmann C, Fuh G, Li B, Christinger HW, McKay P, de Vos AM, Lowman HB. Selection and analysis of an optimized anti-VEGF antibody: crystal structure of an affinity-matured Fab in complex with antigen. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:865–881. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan AM, Eppler DB, Hagler KE, Bruner RH, Thomford PJ, Hall RL, Shopp GM, O'Neill CA. Preclinical safety evaluation of rhu-MAbVEGF, an antiangiogenic humanized monoclonal antibody. Toxicol Pathol. 1999;27:78–86. doi: 10.1177/019262339902700115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veenendaal LM, Jin H, Ran S, Cheung L, Navone N, Marks JW, Waltenberger J, Thorpe P, Rosenblum MG. In vitro and in vivo studies of a VEGF121/rGelonin chimeric fusion toxin targeting the neovasculature of solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7866–7871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122157899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stirpe F, Olsnes S, Pihl A. Gelonin, a new inhibitor of protein synthesis, nontoxic to intact cells. Isolation, characterization, and preparation of cytotoxic complexes with concanavalin A. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:6947–6953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenblum MG, Cheung L, Kim SK, Mujoo K, Donato NJ, Murray JL. Cellular resistance to the antimelanoma immunotoxin ZME-gelonin and strategies to target resistant cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;42:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s002620050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenblum MG, Zuckerman JE, Marks JW, Rotbein J, Allen WR. A gelonin-containing immunotoxin directed against human breast carcinoma. Mol Biother. 1992;4:122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenblum MG, Murray JL, Cheung L, Rifkin R, Salmon S, Bartholomew R. A specific and potent immunotoxin composed of antibody ZME-018 and the plant toxin gelonin. Mol Biother. 1991;3:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y, Xu Q, Rosenblum MG, Scheinberg DA. Antileukemic activity of recombinant humanized M195-gelonin immunotoxin in nude mice. Leukemia. 1996;10:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talpaz M, Kantarjian H, Freireich E, Lopez V, Zhang W, Cortes-Franco J, Scheinberg D, Rosenblum MG. Phase I clinical trial of the anti-CD-33 immunotoxin HuM195/rGel. Abstract R5362, 94th Annual Meeting, American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;44:1066. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ran S, Huang X, Downes A, Thorpe PE. Evaluation of novel antimouse VEGFR2 antibodies as potential antiangiogenic or vascular targeting agents for tumor therapy. Neoplasia. 2003;5:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Axelsson K, Ljung BM, Moore DH, II, Thor AD, Chew KL, Edgerton SM, Smith HS, Mayall BH. Tumor angiogenesis as a prognostic assay for invasive ductal breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:997–1008. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.13.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balsari A, Maier JA, Colnaghi MI, Menard S. Correlation between tumor vascularity, vascular endothelial growth factor production by tumor cells, serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels, and serum angiogenic activity in patients with breast carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1999;79:897–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bosari S, Leek AK, DeLellis RA, Wiley BD, Heatley GJ, Silverman ML. Microvessel quantitation and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:755–761. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90344-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bottini A, Berruti A, Bersiga A, Brizzi MP, Allevi G, Bolsi G, Aguggini S, Brunelli A, Betri E, Generali D, et al. Changes in microvessel density as assessed by CD34 antibodies after primary chemotherapy in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1816–1821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu JS, Lee WJ, Chang TC, Chang KJ, Hsu HC. Correlation between tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in breast cancer. J Formos Med Assoc. 1995;94:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakopoulou L, Stefanaki K, Panayotopoulou E, Giannopoulou I, Athanassiadou P, Gakiopoulou-Givalou H, Louvrou A. Expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2/Flk-1 in breast carcinomas: correlation with proliferation. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:863–870. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.126879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown LF, Guidi AJ, Schnitt SJ, Van De Water L, Iruela-Arispe ML, Yeo TK, Tognazzi K, Dvorak HF. Vascular stroma formation in carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, and metastatic carcinoma of the breast. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1041–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, Tognazzi K, Guidi AJ, Dvorak HF, Senger DR, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:86–91. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hotz HG, Gill PS, Masood R, Hotz B, Buhr HJ, Foitzik T, Hines OJ, Reber HA. Specific targeting of tumor vasculature by diphtheria toxin—vascular endothelial growth factor fusion protein reduces angiogenesis and growth of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cobleigh MA, Langmuir VK, Sledge GW, Miller KD, Haney L, Novotny WF, Reimann JD, Vassel D. A phase I/II dose-escalation trial of bevacizumab in previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(5 Suppl 16):117–124. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaheen RM, Davis DW, Liu W, Zebrowski BK, Wilson MR, Bucana CD, McConkey DJ, McMahon G, Ellis LM. Antiangiogenic therapy targeting the tyrosine kinase receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibits the growth of colon cancer liver metastasis and induces tumor and endothelial cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5412–5416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seon BK, Matsuno F, Haruta Y, Kondo M, Barcos M. Longlasting complete inhibition of human solid tumors in SCID mice by targeting endothelial cells of tumor vasculature with antihuman endoglin immunotoxin. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1031–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Honkoop AH, van Diest PJ, de Jong JS, Linn SC, Giaccone G, Hoekman K, Wagstaff J, Pinedo HM. Prognostic role of clinical, pathological and biological characteristics in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:621–626. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vartanian RK, Weidner N. Correlation of intratumoral endothelial cell proliferation with microvessel density (tumor angiogenesis) and tumor cell proliferation in breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1188–1194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siemann DW, Mercer E, Lepler S, Rojiani AM. Vascular targeting agents enhance chemotherapeutic agent activities in solid tumor therapy. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:1–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedley RB, El Emir E, Flynn AA, Boxer GM, Dearling J, Raleigh JA, Hill SA, Stuart S, Motha R, Begent RH. Synergy between vascular targeting agents and antibody-directed therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1524–1531. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murata R, Overgaard J, Horsman MR. Combretastatin A-4 disodium phosphate: a vascular targeting agent that improves that improves the anti-tumor effects of hyperthermia, radiation, and mild thermoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:1018–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schnell R, Vitetta E, Schindler J, Borchmann P, Barth S, Ghetie V, Hell K, rillich S, Diehl V, Engert A. Treatment of refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma patients with an anti-CD25 ricin-A chain immunotoxin. Leukemia. 2000;14:129–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, White JD, Stetler-Stevenson M, Jaffe ES, Giardina S, Waldmann TA, Pastan I. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38 (LMB-2) in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1622–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.LeMaistre CF, Saleh MN, Kuzel TM, Foss F, Platanias LC, Schwartz G, Ratain M, Rook A, Freytes CO, Craig F, et al. Phase I trial of a ligand fusion-protein (DAB389IL-2) in lymphomas expressing the receptor for interleukin-2. Blood. 1998;91:399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheung LH, Marks JW, Rosenblum MG. Development of “designer toxins” with reduced antigenicity and size. Abstract 3790, 95th Annual Meeting, American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;45:874. [Google Scholar]