Abstract

Neuroectodermal tumor cells, like neural crest (NC) cells, are pluripotent, proliferative, and migratory. We tested the hypothesis that genetic programs essential to NC development are activated in neuroectodermal tumors. We examined the expression of transcription factors PAX3, PAX7, AP-2α, and SOX10 in human embryos and neuroectodermal tumors: neurofibroma, schwannoma, neuroblastoma, malignant nerve sheath tumor, melanoma, medulloblastoma, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and Ewing's sarcoma. We also examined the expression of P0, ERBB3, and STX, targets of SOX10, AP-2α, and PAX3, respectively. PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10 were expressed sequentially in human NC development, whereas PAX7 was restricted to mesoderm. Tumors expressed PAX3, AP-2α, SOX10, and PAX7 in specific combinations. SOX10 and AP-2α were expressed in relatively differentiated neoplasms. The early NC marker, PAX3, and its homologue, PAX7, were detected in poorly differentiated tumors and tumors with malignant potential. Expression of NC transcription factors and target genes correlated. Transcription factors essential to NC development are thus present in neuroectodermal tumors. Correlation of specific NC transcription factors with phenotype, and with expression of specific downstream genes, provides evidence that these transcription factors actively influence gene expression and tumor behavior. These findings suggest that PAX3, PAX7, AP-2α, and SOX10 are potential markers of prognosis and targets for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Neural crest, neuroectodermal tumor, glia, melanocyte, development

Introduction

Embryonic neural crest (NC) cells and cancer cells both migrate from their sites of origin, proliferate, and colonize distant sites in specific locations. The normal process of NC development, in which primitive, pluripotent, migratory cells give rise to diverse mature tissues, is partly reversed when, within these tissues, malignancies arise. We propose that the similarity between NC cells and neoplastic cells of NC-derived tissues is not merely superficial, but rather reflects an inappropriate activation of genetic instructions used in NC development. We tested two predictions of this theory: genes that control NC development would be expressed in more primitive tumors. We determined a set of transcription factors essential for NC development and sequentially expressed as NC cells mature. We then analyzed the expression of these markers in tumors of NC-derived tissues, of varying growth dysregulation and malignant potential. As proteins crucial to NC development are expressed in embryonic neuroectoderm prior to NC differentiation, we also tested the hypothesis that these proteins are present in tumors with primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNETs) histology. Lastly, to test whether NC transcription factors detected in neuroectodermal tumors actively influenced tumor phenotype, we analyzed the expression of known downstream target genes.

The transcription factors AP-2α, PAX3, and SOX10 are expressed in embryos by NC-derived cells, and each of these proteins is required for normal NC development [1–5]. The temporal expression patterns of these proteins, however, vary significantly. PAX3 is expressed by NC precursors prior to neurulation, and is required to maintain their competence for NC induction [7,8]. AP-2α expression begins later than that of PAX3 in premigratory NC cells [9]. Later in development, PAX3 and AP-2α are downregulated in NC-derived cells [7,9], except melanocytes [10,11]. SOX10, in contrast, is expressed only by migratory NC-derived cells, and persists in terminally differentiated melanocytes and glia [12]. We used the overlapping expression patterns of PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10 both to identify NC-derived cells and to gauge their level of development. We also analyzed the expression of PAX7, a protein homologous to PAX3 that in mice is expressed in the mesoderm and in the mesectodermal subset of cranial NC cells [6]. We thus used PAX7 as a marker of mesodermal and mesectodermal phenotype.

Several lines of evidence indicate that PAX3, AP-2α, SOX10, and PAX7 regulate cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation, both in development and in neoplasia. PAX3 and PAX7 promote survival in embryonic and malignant cells, whereas experimentally decreased PAX7 [13] or PAX3 [13–15] expression leads to cell death in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma [13], melanoma, and myoblast [14] cells. Roles have also been proposed for PAX3 in promoting metastasis [16] and opposing differentiation [17]. Studies on transgenic mice lacking AP-2α have indicated that this protein promotes the survival of normal embryonic cells, inhibits apoptosis, and promotes proliferation [2,18]. Studies of human cancers, however, suggest that AP-2α may act as a tumor suppressor [19–22]. Studies of SOX10 -/- mice have demonstrated that SOX10 is essential for survival of NC-derived cells and for glial differentiation [23]. Studies of induced SOX10 expression in NC-derived stem cells in vitro have demonstrated that SOX10 maintains these cells in a multipotent, proliferative state, while permitting glial differentiation [24]. These findings suggest a variety of mechanisms by which PAX3, PAX7, AP-2α, and SOX10 might exert clinically significant effects on the behavior of malignant cells.

As an initial measure of the effect of expressing SOX10, AP-2α, and PAX3, we examined the expression of genes known to be regulated by these transcription factors. Targets of SOX10 include P0 and MITF [25,26]. AP-2α enhances the expression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 [27]. Mayanil et al. [28] identified several genes upregulated by PAX3, including MYOD and STX.

The current investigation is intended to build on previous work by other investigators, in which transcripts encoding AP-2α, PAX3, PAX7, and SOX10 have individually been detected in cell lines or malignant tumors [12,14,17, 19–22,29]. In accord with our hypotheses, we detected NC markers AP-2α, PAX3, PAX7, and SOX10 in specific combinations in human NC cells and in human tumors. These combinations varied according to types of tumor and their clinical features. Kho et al. [30] recently used microarray analysis of mRNA to demonstrate similarities in gene expression in medulloblastoma (MBL) and early postnatal cerebellum, supporting the idea that these tumors inappropriately activate developmental programs. Our findings similarly support the hypothesis that, in their malignant behavior, neuroectodermal tumor cells draw on the developmental program of their ontologic ancestors. The transcription factors factors that direct this program in normal development are both potential markers of prognosis and candidate targets for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and Methods

All tissues were obtained by surgical resection. Specimens were obtained from the archives of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), Department of Pathology (New York, NY) and the New York Presbyterian Hospital (NYPH), Presbyterian Campus, Department of Pathology (New York, NY). Total RNA from neuroblastomas was purified from snap-frozen tissue resected at MSKCC, whereas total RNA from MBLs was generously provided by Dr. James M. Olson (Fred Huchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). The use of human tissue specimens was reviewed and approved by the Columbia University/NYPH and MSKCC Institutional Review Boards. For immunocytochemistry, the tissue was fixed in neutral-buffered formalin overnight, then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut to a thickness of 4 to 6 µm and placed on treated slides.

For immunocytochemistry, tissue sections were prepared by immersion in xylene, rehydration in ethanol, treatment with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol, and heating in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 5.5, in a microwave oven on high power for 10 minutes. The tissue was incubated with 3% serum and then incubated overnight with primary antibodies, diluted, if necessary with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.3% Triton X (PBS-TX). Sections were then washed and incubated for 2 to 16 hours with biotinylated or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, diluted 1:200. After washes, sections were incubated with avidin conjugated either to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or a second fluorophore. HRP-labeled slides were stained with 0.05% diaminobenzidine (DAB) as recommended in the AB Peroxidase Kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Sections were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin or, for immunofluorescence, with bisbenzamide.

Several primary antibodies were used. For SOX10, polyclonal antibodies, raised in goat (used diluted 1:100), were generously provided by Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA; sc-17342, sc-17343), and a mouse monoclonal antibody (used diluted 1:10) was generously provided by Dr. David Anderson (California Institute of Technology, Sacramento, CA). The SOX10 polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies were tested on all tumor samples and produced identical results. Two polyclonal antisera to PAX3 made in rabbit (both used diluted 1:300) were generously provided by Dr. Gerald Grosveld (St. Jude's Children's Hospital, Memphis, TN) and by Dr. Frank Rauscher III and Dr. William Fredericks (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA). All positive results were confirmed using both PAX3 antisera. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to AP-2α (3B5; developed by Dr. Trevor Williams) and PAX7 (PAX7; developed by Dr. Atsushi Kawakami) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). Both were used undiluted. PAX3 and PAX7 antibodies labeled overlapping—but discrete—sets of cells, indicating no cross-reactivity. Antibodies to P0 (used at 1:100) and ERBB3 (used at 1:25) were obtained (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies included: biotinylated goat antimouse (Vector), biotinylated rabbit antigoat (Vector), biotinylated goat antirabbit (Jackson Immunochemicals, West Grove, PA), ALEXA-conjugated goat antimouse (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and ALEXA-conjugated donkey antigoat (Molecular Probes). To visualize biotinylated antibodies, slides were treated either with the ABC Peroxidase Kit (Vector), or, for immunofluorescence, with streptavidin ALEXA (Molecular Probes).

Quantitative analysis of mRNA abundance was performed by microarray hybridization as previously described [31] and by quantitative PCR. For microarray analysis, primary neuroblastoma samples were snap-frozen, and total RNA was purified. cDNA was synthesized using T7 poly dT primers, and in vitro transcription was performed using biotinylated ribonucleotides. The products were then hybridized to Affymetrix human U95 microarrays and scanned using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 4.0 or 5.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

For quantitative PCR, total RNA was purified from snap-frozen neuroblastoma and MBL samples. One-step real-time RT-PCR was then carried out, using various techniques. β-Actin, SOX10, and AP-2α were quantified using SYBR green detection, on a Roche LightCycler Instrument, using the Roche LightCycler RNA Amplification Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, cat no. 2015137). The primers for β-actin were CCTCGCCTTTGCCGATC and CGCAGCTCATTGTAGAAGGTG, for SOX10 were CTGAGTTGGACCAGTACCTG and GGCTGATGGTCAGAGTAGTC, and for AP-2α were AGCAGTAGCTGAATTTCTCAAC and TGAGGTACATTTTGTCCATG. STX was quantified using FRET detection, on the Roche LightCycler platform, with the Invitrogen SuperScript III Platinum One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, cat no. 12574-018), with the primers AGACATCTCAGAGATCGAAG and TAATATCTCCAGGCTTCAGG, and the probes ATGAAAGCATCAAGCACAACATCC-fluorescein and red640-CCAGCCTCGTCCAAATGGAG-phosphate.

Results

NC Markers in Human Embryos

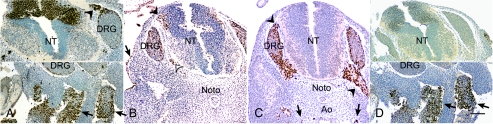

Distinct protein expression patterns of PAX7, PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10 were demonstrated in truncal sections of human embryos at 8 weeks of gestation (Figure 1, A–D). Antibodies to PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10 labeled NC cells throughout the range of developmental states, from before the beginning of migration to colonization of specific sites. Antibodies to AP-2α and PAX3 also labeled cells not on NC derivation. PAX3 was expressed in the dorsal neural tube (NT), in cells along the migratory pathway by which NC cells exit the dorsal NT, and in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG). PAX3 was also expressed in mesodermal cells in the dermatomyotomes (Figure 1A). AP-2α, in contrast, was expressed in the dorsal NT only by cells at the lateral margins, the expected location of NC cells migrating out of the NT. Cells in the DRG and in the epithelium also expressed AP-2α (Figure 1B). SOX10 was expressed by NC-derived cells only outside the NT, in the DRG, in the ventral roots, and in the para-aortic sympathetic tissue (Figure 1C). A group of cells around the stomach, NC-derived precursors migrating to form the enteric nervous system, also expressed SOX10 (data not shown). In these truncal sections, no NC-derived cells expressed PAX7. Thus, a pattern emerged in which PAX3 was prominent in the dorsal NT, where NC precursors begin their migration and AP-2α and SOX10 were upregulated at progressively farther points along the migratory pathways of the NC-derived cells. The appearance of each marker in NC precursors and NC cells corresponded to points along their developmental progression.

Figure 1.

In truncal sections of a human embryo at approximately 8 weeks of gestation, antibodies PAX3, AP-2α, SOX10, or PAX7 specifically labeled NC-derived cells according to their state of differentiation. Slides were labeled by immunocytochemistry using HRP and DAB, with hematoxylin counterstaining. (A) Top panel: Antibodies to PAX3 labeled cells of the dorsal neural tube (NT), dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and migrating NC-derived cells along an intervening trajectory (arrowhead), while also labeling dermatomyotomal cells (arrows, lower panel). (B) Antibodies to AP-2α labeled migratory NC-derived cells as they exit the dorsal NT (black arrowhead), as well as cells of the DRG, the ventral root, as it leaves the NT (white arrowhead), and the embryonic epithelium (arrow). Noto = notochord. (C) Antibodies to SOX10 labeled cells in the DRG, the dorsal and ventral roots (arrowheads), and the para-aortic sympathetic tissue (arrow). Ao = aorta. (D) Upper Panel: Antibodies to PAX7 labeled no cells of the NT or NC at this level, but, like antibodies to PAX3, labeled cells of the dermatomyotome (arrowheads, lower panel). Bar = 100 µm.

NC Marker Expression in Mature NC-Derived Tissues

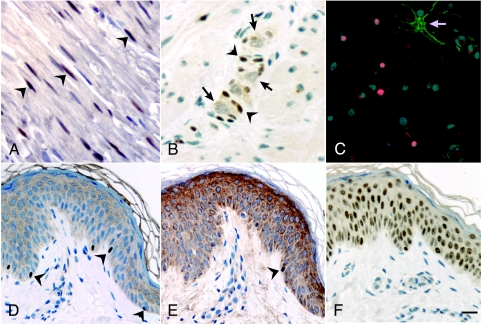

Specimens of the peripheral nerve, skin, colon, adrenal gland, and brain were tested with antibodies to AP-2α, PAX3, PAX7, and SOX10 to ascertain expression patterns in differentiated NC-derived cells (Figure 2). Antibodies to SOX10 labeled Schwann cells, enteric glia, and melanocytes; also labeled were oligodendrocytes and glial cells of NT rather than NC derivation (Figure 2, A–D). Antibodies to PAX3 and AP-2α did not label any glial cells, but labeled melanocytes (Figure 2E) AP-2α, labeling all cells in the epidermis (Figure 2F). Antibodies to PAX7 labeled no cells in mature tissues tested. Among NC-derived cells, therefore, glia expressed SOX10, whereas melanocytes expressed SOX10, PAX3, and AP-2α. Enteric neurons and adrenal medullary cells, in contrast, expressed none of the markers. Compared to their more widespread expression in the embryo, the expression of all three transcription factors was relatively restricted.

Figure 2.

NC markers labeled specific terminally differentiated cells, visualized by using immunocytochemistry. (A) SOX10 was expressed by Schwann cells in a peripheral nerve (arrowheads mark examples). (B) SOX10 was expressed by enteric glia (arrowheads mark examples), seen here surrounding enteric neurons (arrows), notable for their large unlabeled nuclei and extensive cytoplasm. (C) Oligodendrocytes in a temporal lobe section expressed SOX10. In this preparation, SOX10 is labeled with Alexa red, GFAP is labeled with Alexa green, and nuclei are counterstained with bisbenzamide. An astrocyte (arrow) strongly expressed GFAP, but did not express SOX10. (D) In a skin biopsy, SOX10 was expressed by melanocytes, identified by their density and position in the basal layer of the epidermis (arrowheads mark examples). (E) Melanocytes labeled with PAX3 antibodies (arrowhead). PAX3-expressing cells were more rare than cells expressing SOX10. (F) All cells within the epidermis expressed AP-2α. Bar = 40 µm.

NC Marker Expression in Benign Neoplasms of NC-Derived Tissues

In schwannoma and neurofibroma, benign peripheral glial tumors, cells expressed NC transcription factors not expressed by normal Schwann cells. Although in all cases SOX10 was prominently expressed, as it was in mature Schwann cells (Figure 3, A and B), schwannomas also expressed AP-2α (three of four cases; Figure 3C), whereas neurofibromas expressed PAX3 (six of six cases; Figure 3D). Neither PAX3 nor PAX7 was detected in schwannomas, and neither AP-2α nor PAX7 was detected in neurofibromas. Thus, the two benign peripheral glial tumors expressed different inappropriate transcription factors, normally expressed during peripheral glial development.

Figure 3.

SOX10, in combination with AP-2α or PAX3, in benign glial neoplasms, demonstrated by immunocytochemistry. SOX10 was expressed by cells in schwannoma (A) and neurofibroma (B). Schwannoma cells expressed AP-2α (C), whereas neurofibroma cells expressed PAX3 (D). Bar = 40 µm.

NC Marker Expression in Malignant Neoplasms of NC-Derived Tissues and PNETs

Malignant tumors of NC lineage are diverse; we analyzed neuroblastomas [14], metastatic melanomas [3], and malignant nerve sheath tumors (MNSTs) [4] to sample malignant variations of a spectrum of NC-derived cell types. In addition, several tumors with primitive neuroectodermal histology were analyzed: 11 MBLs (MBLs; eight classic, three desmoplastic), 2 supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors (SPNETs), and 3 Ewing's sarcomas (ES). As a primary CNS tumors, MBL and SPNET derive from the NT, rather than the NC. The histogenesis of ES, in contrast, is unclear, but aspects of a NC-derived phenotype have been noted [32].

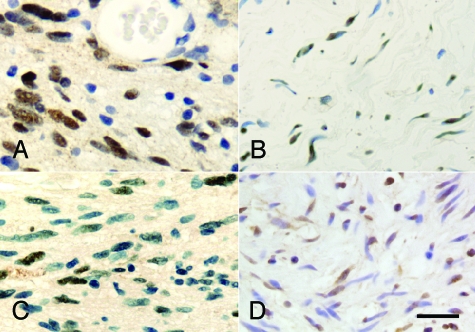

In neuroblastoma, abnormal NC transcription factor expression was again noted in glial elements: SOX10 and AP-2α were upregulated in elongated, Schwann-like cells, as found in benign schwannomas (Figure 4, A and B). Neuroblastoma is, however, a heterogeneous set of tumors, with variable prognoses and variable prominence of Schwannlike cells. In addition to the relatively intense labeling of Schwann-like cells by antibodies to SOX10 and AP-2α, a relatively faint labeling of patches of neuroblasts was noted in poorly differentiated tumors (Figure 4, C and D). We analyzed three ganglioneuromas and 11 stage IV tumors. We found SOX10 and AP-2α to be expressed in all ganglioneuromas, and 11 stage IV tumors, We found SOX10 and AP-2α to be expressed in all ganglioneuromas and some stage IV neuroblastomas, as enumerated in Table 1.

Figure 4.

SOX10 and AP-2α were expressed in neuroblastoma cells, demonstrated by immunocytochemistry. In ganglioneuroma, antibodies to SOX10 (A) or AP-2α (B) labeled elongated Schwann-like cells. In grade IV neuroblastoma, antibodies to SOX10 (C) or AP-2α (D) labeled round, undifferentiated cells. The labeling was weaker in cells of stage IV neuroblastomas than ganglioneuromas. Bar = 20 mm.

Table 1.

Patterns of Marker Expression.

| Tissue | SOX10 | AP2 | PAX3 | PAX7 |

| Truncal neural crest | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| Peripheral nerve | Schwann cells | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Skin | Melanocytes | All cells | Melanocytes | Negative |

| Colon | Enteric glia | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Adrenal medulla | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Temporal lobe | Oligodendrocytes | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Schwannoma | 4/4 | 3/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Neurofibroma | 6/6 | 0/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 |

| Ganglioneuroma | 3/3 | 3/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| Neuroblastoma | 8/11 | 2/11 | 0/11 | 0/11 |

| MNST | 4/4 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 2/4 |

| Melanoma | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 0/3 |

| ES | 2/3 | 2/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| Pineal region PNET | 0/2 | 0/2 | 1/2 | 0/2 |

| Classic MBL | 0/8 | 0/8 | 6/8 | 0/8 |

| Desmoplastic MBL | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

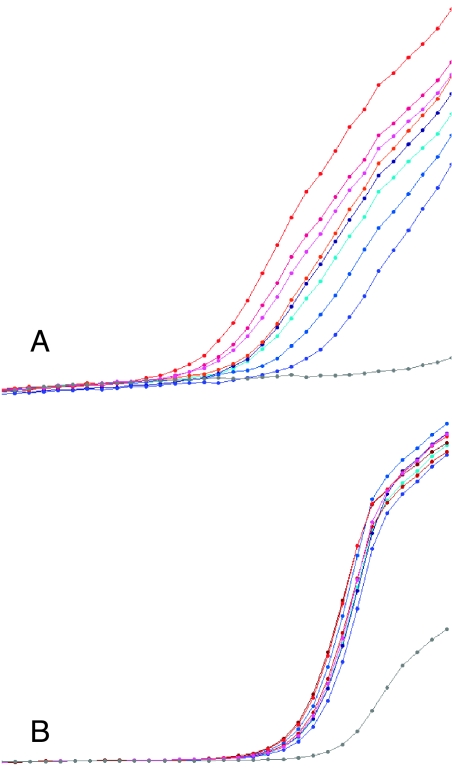

The variation in the intensity of labeling led us to compare the abundance of SOX10 and AP-2α mRNA, determined by both microarray hybridization and quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Microarray data were available for all three ganglioneuromas included in the immunocytochemical analysis, and for six of the stage IV neuroblastomas. SOX10 and AP-2α mRNA were substantially more abundant in ganglioneuromas, where SOX10 and AP-2α where expressed only in Schwann-like cells, than in stage IV tumors, where the markers were expressed by neuroblasts (Figure 4; Graph 1). The very low levels of SOX10 and AP-2α mRNA detected in the stage IV tumors likely reflect both the low level of expression in positive cells, as seen by immunocytochemistry, and the infrequency of patches of positive cells within the tumor. In contrast, expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase β, used as a control, did not vary with tumor type (Graph 1). We found similar results using real-time RT-PCR on an overlapping set of six ganglioneuromas and seven stage IV neuroblastomas (Graph 2). Greater expression of SOX10 and AP-2α thus correlated with glial differentiation, and lower expression with poor differentiation.

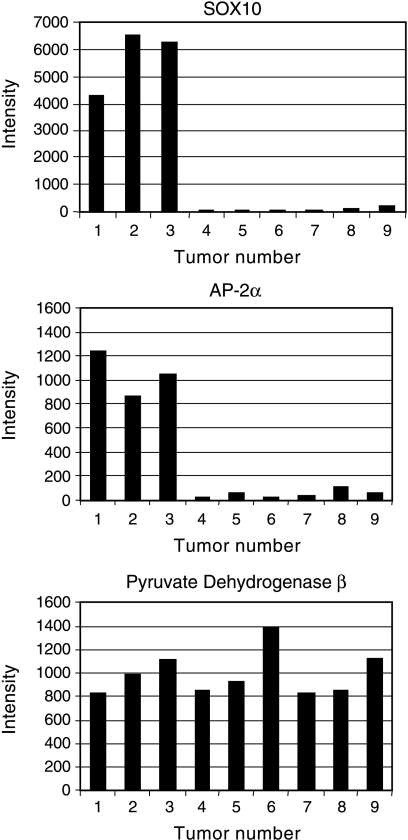

Graph 1.

SOX10 and AP-2α mRNA, detected by microarray hybridization, were more abundant in ganglioneuromas than in stage IV neuroblastomas. Affymetrix intensity scores are plotted for each of the nine tumors. Lanes 1–3: Scores for ganglioneuromas; lanes 4–9: scores from stage IV neuroblastomas. Abundance of lactate dehydrogenase mRNA, evaluated as a control, did not vary with tumor type.

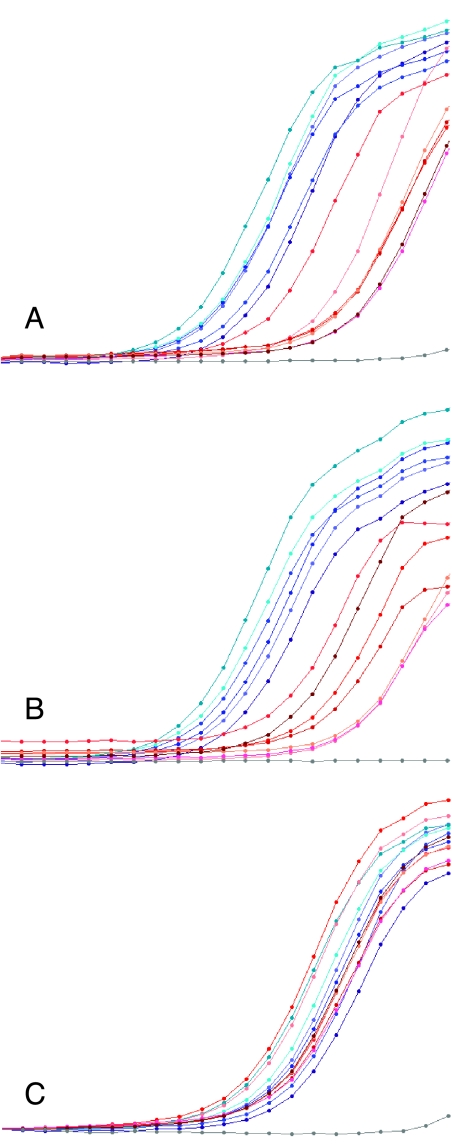

Graph 2.

SOX10 (A) and AP-2α (B) mRNA abundance, measured by real-time RT-PCR with SYBR green detection, was greater in ganglioneuromas than in stage IV neuroblastomas. Each curve represents fluorescence intensity per cycle for an individual tumor. Ganglioneuromas are shown in shades of blue, and neuroblastomas in shades of red. Negative control with no template is shown in gray. All ganglioneuroma curves are to the left of the neuroblastoma curves, indicating greater abundance of specific message. For SOX10, the average crossing point for ganglioneuroma was 18, and for neuroblastoma was 24, indicating a 64-fold difference. For AP-2α, the average crossing points were 25 and 30, indicating a 32-fold difference. In contrast, β-actin mRNA abundance was similar among all tumors and did not vary with tumor type (C).

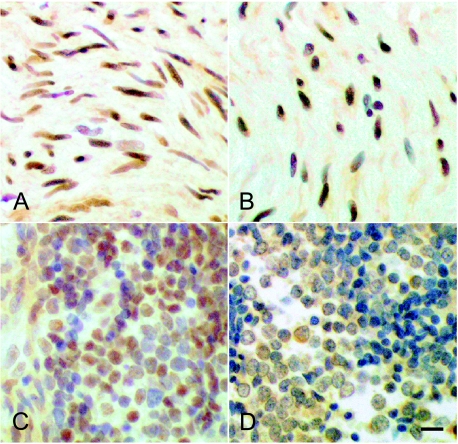

MNSTs, like neurofibromas, expressed SOX10 and PAX3 (Figure 5, A and C). In addition, in two of four cases, AP-2α was detected in rare cells (Figure 5B); and in two of four cases, PAX7 was prominently expressed (Figure 5D). The common finding of inappropriate PAX3 expression in neurofibroma and MNST suggests that this developmentally regulated transcription factor may play a role in these related tumors. Because it is expressed in the premalignant lesion, PAX3 would not appear to be sufficient to confer malignancy, but it may yet be necessary for tumor growth and transformation.

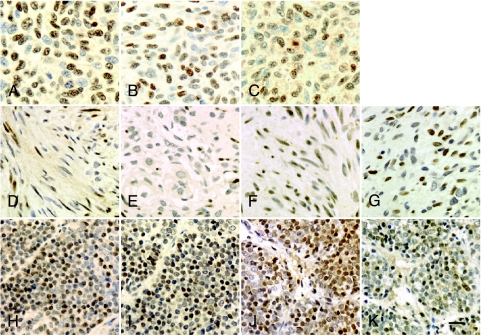

Figure 5.

Marker expression in melanoma, MNST, and ES cells. (A–C) Melanoma cells labeled with antibodies to SOX10 (A), AP-2α (B), and PAX3 (C). Most cells express each of the markers. (D–G) MNST cells, labeled with antisera to SOX10 (D), AP-2α (E), PAX3 (F), and PAX7 (G). Cells expressing SOX10 and AP-2α are relatively scattered, whereas PAX3 and PAX7 are more uniformly expressed. (H–K) ES cells labeled with antisera to SOX10 (H), AP-2α (I), PAX3 (J), and PAX7 (K). As in melanoma, markers are expressed by almost all cells. Bar = 40 µm.

In ES, as in MNST, exuberant expression of NC transcription factors was noted: SOX10 in two of three cases, AP-2α in two of three cases, PAX3 in three of three cases, and PAX7 in three of three cases (Figure 5, E–H). In melanoma, SOX10, AP-2α, and PAX3 were detected in almost all cells in three of three cases (Figure 5, I–K).

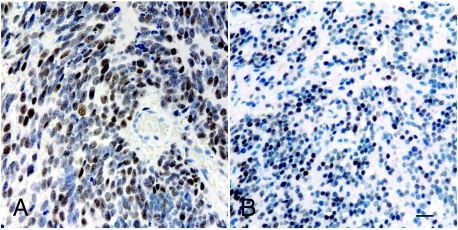

In MBL and SPNET, both intracranial PNETs, only PAX3 was detected. Using immunocytochemistry, PAX3 was detected in classic MBL (six of eight cases) but not in the desmoplastic variant (none of three cases). PAX3 was also detected in one of two SPNETs. In each case, PAX3 was expressed in discrete regions within the tumor, by almost all cells within the regions (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

PAX3 was expressed by clusters of cells in classic MBL (A) and SPNET (B). This patchy distribution may lead to undercounting of the cases in which PAX3 is detected, as a small sample from a large tumor may not include discrete regions of PAX3 expression. Bar = 40 µm.

Downstream Targets of SOX10, AP-2α, and PAX3 Corresponded with Transcription Factor Expression

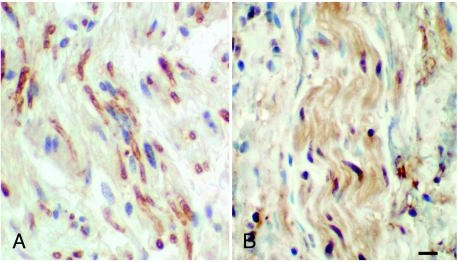

Microarray data (not shown) indicated that several targets of SOX10 and AP-2α were expressed at higher levels in ganglioneuroma than in stage IV neuroblastoma. Differentially expressed SOX10 targets included P0 and PLP, but not MITF. Differentially expressed targets of AP-2α included ERBB2 and ERBB3. Immunocytochemistry confirmed widespread expression of P0 (Figure 7A) and PLP (not shown) in three of three ganglioneuromas, with markedly less expression in neuroblastoma (Figure 7B). Similarly, immunocytochemistry confirmed widespread expression of ERBB3 in three of three ganglioneuromas, with only rare expression in neuroblastomas. ERBB2 was not detected with reliable intensity in ganglioneuromas or neuroblastomas.

Figure 7.

Expression by ganglioneuroma cells of genes regulated by SOX10 and AP-2α. P0 (A), a downstream target of SOX10, and ERBB3 (B), a downstream target of AP-2α, visualized by immunocytochemistry. Label was primarily seen in elongated cells resembling Schwann cells. Bar = 20 µm.

The finding of PAX3 in classic but not desmoplastic MBL predicted that genes regulated by PAX3 would be differentially expressed in classic and desmoplastic tumors. Mayanil et al. [28] demonstrated that PAX3 positively regulated the expression of several genes in the DAOY MBL cell line, including MYOD and STX. Immunostaining did not detect expression of MYOD in any MBLs (not shown), whereas RT-PCR detected the expression of STX in both classic and desmoplastic tumors. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR, however, clearly distinguished higher expression levels in four of four classic MBLs than in four of four desmoplastic cases (Graph 3).

Graph 3.

STX mRNA, measured by real-time RT-PCR with FRET detection, was greater in classic than in desmoplastic MBLs (A). Each curve represents intensity per cycle for an individual tumor. Classic MBLs are shown in shades of red, and desmoplastic tumors in shades of blue. Negative control with no template is shown in gray. All classic MBL curves are to the left of the desmoplastic variant curves, indicating greater expression of STX mRNA. The average crossing point for classic MBLs was 40, and for desmoplastic tumors was 46, indicating an eight-fold difference. In contrast, β-actin mRNA abundance was similar among all tumors and did not vary with tumor type (B). Melting point analysis revealed that the signal from the negative control in panel (B) was due to nonspecific PCR products (not shown).

Discussion

Tumors Express NC Markers in a Manner That Echoes Developmental Progression

Our hypothesis, that cellular programs crucial to normal development are inappropriately activated in neuroectodermal tumors, predicts that genes directing these programs will be upregulated. We found that three genes essential to normal NC development (PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10) were upregulated in a variety of neuroectodermal tumors. Although the expression of these genes fulfills a minimal requirement of our hypothesis, an open question is whether they play an active role in defining tumor behavior. Although we did not directly test the function of these genes in tumor cells, we predicted that genes expressed earlier in NC development would be expressed in more malignant, poorly differentiated tumors. We tested this prediction by analyzing the pattern of NC marker expression in embryos, differentiated tissues, and neuroectodermal tumors.

We demonstrated a developmental progression in which NC precursors express PAX3, and then migratory NC cells express first AP-2α then SOX10. Although SOX10 is upregulated later in the course of NC development, the migrating NC cells that begin to express it are nevertheless proliferative and undifferentiated. Each of these markers persisted in some differentiated cell types: postembryonic glia expressed SOX10, whereas melanocytes expressed all three NC markers. Thus, each marker participated in a spectrum of differentiated states. For PAX3, the range included the least differentiated NC precursors, but also included differentiated melanocytes. In contrast, for SOX10, the range included the relatively differentiated migratory NC cells, and a broader range of mature NC-derived cell types. Within this model of NC markers defining ranges of differentiation, the expression patterns observed in tumors fall into place.

PAX3 and MBL

The relatively early NC marker, PAX3, was upregulated in malignant tumors in NC- or NT-derived tissues, including melanoma, MNST, classic MBL, and SPNET. Among MBLs, PAX3 expression distinguished classic MBL from the more differentiated desmoplastic MBL. Although PAX3 was expressed in one benign tumor, neurofibroma, this lesion has the potential to undergo malignant transformation to MNST. Upregulation of PAX3 thus occurred in malignant and premalignant tumors, and correlated among MBLs, with poor differentiation. Expression of the PAX3 homologue, PAX7, was limited more consistently to malignancies.

Although we found PAX3 to be frequently expressed in MBL, we never found PAX3 in the desmoplastic variant. Interestingly, this variant is associated with abnormalities of the sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway [33], a factor whose domain of expression is complementary to PAX3. SHH is distributed in a gradient highest in the ventral NT [34], whereas PAX3 is expressed in the dorsal NT. PAX3 expression thus defines a set of cells that normally do not encounter SHH. The expression of PAX3 in MBL may thus identify a subset of MBLs in which SHH activity is qualitatively different. Correlation of PAX3 and genes involved in SHH signaling, including SMOOTHENED, PATCHED, and GLI, would evaluate this interpretation.

SOX10, PAX3, and Differentiation

In contrast to PAX3, the relatively late marker, SOX10, was expressed in malignant, premalignant, and benign tumors of NC derivation. Thus, among tumors, as in embryonic and mature tissues, SOX10 expression occurred in a range of phenotypes. In tumors, SOX10 was generally detected in combination with other NC markers. The coexpression of PAX3 predicted malignant phenotype or potential, whereas the coexpression of SOX10 and AP-2α, in the absence of PAX3, was seen in both malignant neuroblastoma and benign schwannoma and ganglioneuroma. The finding that undifferentiated neuroblastic cells express lower levels of SOX10 and AP-2α than the relatively differentiated Schwann-like cells of ganglioneuroma suggests that the dose of these transcription factors may play a role in regulating differentiation. Similarly, other investigators have noted the downregulation of SOX10 with malignant transformation, in Schwann cells in vitro [35], and in MNST biopsies [36]. It is clear, however, that although PAX3 and SOX10 expression was consistent with a range of phenotypes in both development and neoplasia, tumors expressing SOX10, but not PAX3, exhibited greater differentiation.

Specificity of Markers for NC Lineage

Expression of AP-2α, PAX3, and SOX10 in the embryo corresponded closely with the NC lineage, as defined embryologically [6]. In their fundamental dysregulation, however, tumor cells may acquire phenotypes not appropriate for their actual lineage, upregulating atypical genes or downregulating typical genes. In a humor tumor, therefore, lineage can be at best inferred from the phenotypes of the tumor cells and their site of origin. The expression of transcription factors thus demonstrates not lineage, but a molecular aspect of phenotype. Although the expression, by tumor cells, of AP-2α, PAX3, or SOX10 cannot establish NC lineage, it does demonstrate a phenotypic resemblance to NC-derived cells. The lack of expression of these markers, conversely, does not inform as to lineage, but represents divergence from a NC phenotype.

Our finding of the expression of multiple NC markers in ES demonstrates a phenotypic resemblance of ES cells to embryonic cells of NC origin. Given the similar migratory and proliferative nature of embryonic NC-derived cells and ES cells, their expression of common transcription factors is likely to be significant. These transcription factors are essential for NC cell proliferation and survival, raising a question of potential clinical importance: whether ES cells and cells of other malignant neuroectodermal tumors share the dependence of NC-derived cells for PAX3, AP-2α, and SOX10.

The expression of PAX7 in extracranial neuroectodermal tumors is inappropriate for cells derived from truncal NC; PAX7 is normally expressed in mesoderm and cranial NC-derived mesectoderm. We detected PAX7 in ES and MNST. The expression of a marker inappropriate to lineage is plausibly understood as the result of severe disruption of differentiation in abnormal malignant cells.

Metastatic Melanoma Can Retain the Melanocytic Pattern of NC Transcription Factors

Melanocytes expressed SOX10, AP-2α, and PAX3 simultaneously, a pattern otherwise observed only in malignancies. The expression of these proteins persisted in the metastatic melanomas that we analyzed. The expression of PAX3 in melanocytes has been controversial. Using immunocytochemistry, Galibert et al. [11] detected PAX3 in a murine melanocyte cell line. Scholl et al. [14], however, did not find transcripts encoding PAX3 in normal melanocytes using in situ hybridization with oligonucleotide probes, and concluded that PAX3 expression was specific to melanoma. Other investigators have correlated the loss of AP-2α with the acquisition of metastatic behavior. The current findings, however, indicate that PAX3 can be expressed in normal melanocytes, whereas AP-2α can be expressed in metastatic melanoma cells. The transformation to malignancy, therefore, did not necessarily disrupt the pattern of marker expression detected by immunocytochemistry in normal melanocytes. The possibility remains that although these markers were expressed at detectable levels, they may have been present in abnormal forms, or at abnormal levels, not discriminated by our methods. The detection of these proteins in melanocytes and metastatic melanoma cells, however, may limit their effectiveness as predictive markers of melanoma behavior or prognosis.

SOX10, AP-2α, and the Nature of Schwann-Like Cells in Neuroblastoma

The origin of Schwann cells within neuroblastomas has been controversial [37–39]. Normal mature Schwann cells expressed SOX10 but not AP-2α. In studies on rodent peripheral nerve, Stewart et al. [40] demonstrated that AP-2α is expressed by immature Schwann cells, is downregulated as Schwann cells mature, and is not subsequently upregulated in response to injury or loss of axonal contacts. We found, however, that AP-2α is expressed by Schwann-like cells in neuroblastomas, and most prominently in ganglioneuromas. Although our finding, that Schwann-like cells express SOX10, is consistent with a glial phenotype, their expression of AP-2α rather indicates that these cells are incompletely differentiated. As such, these cells may be the progeny of neoplastic cells that have retained an ability to differentiate partially. The known association of a Schwann-like stroma with a favorable prognosis [37,38] may thus reflect an underlying ability of tumor cells to differentiate into stroma. Regardless of the underlying principle, however, the current findings suggest that expression of SOX10 and AP-2α, given their correlation with Schwann-like stroma and with ganglioneuroma, may be a favorable prognostic indicator.

Expression of Downstream Targets Suggests an Active Role for NC Transcription Factors

We propose that specific NC transcription factors influence the phenotype of neuroectodermal tumors. This hypothesis may ultimately be tested by genetic manipulation in vitro, or in animal models. We sought preliminary evidence for the effect of the NC transcription factors in the expression of their downstream targets. As predicted, P0 and ERBB3, respective targets of SOX10 and AP-2α, were relatively highly expressed in ganglioneuroma, compared with stage IV neuroblastoma. Similarly, STX, a gene upregulated by PAX3, was relatively highly expressed in classic MBL, compared with the desmoplastic variant. These findings provide evidence that the NC transcription factors are not merely markers of tumor phenotype, but rather determinants.

Epithelial and Mesenchymal Phenotypes in Benign and Malignant Tumors

We predicted that PAX3, PAX7, AP-2α, and SOX10, key elements in the genetic control of NC development, would be expressed in tumors of NC-derived tissues and tumors of primitive neuroectodermal histology. We found SOX10 to be expressed in diverse tumors of NC derivation, commonly in combination with AP-2α, PAX3, or PAX7. We also predicted that the expression of the earlier NC markers would correlate with malignancy. We found the later NC markers, SOX10 and AP-2α, in relatively benign neoplasms: schwannomas and ganglioneuromas. In contrast, although we detected PAX3 in non-neoplastic melanocytes, among tumors, PAX3 expression coincided with malignant phenotype, or, in the case of neurofibroma, malignant potential. Similarly, PAX7 expression was only seen in malignant tumors.

Although PAX3 is the earliest of the NC markers tested, and PAX7 is a close homologue, it is intriguing that both are genes robustly expressed in mesoderm. In contrast, SOX10 and AP-2α are restricted to ectoderm. Epithelial- mesechymal transformation is an essential feature of early NC development [41] that has also been implicated in malignant behavior in several tumors types [42]. The relationship between epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and the expression, in malignant NC-derived tumors, of markers expressed jointly by NC and mesodermal cells is thus striking.

In summary, we found NC markers, SOX10, AP-2α, PAX3, and PAX7, were expressed in neuroectodermal tumors, in a manner that varied with clinical and histopathologic features, including the expression of downstream targets. The correlation of tumor phenotype with specific NC markers suggests that these transcription factors play a significant role in directing tumor behavior. These findings point to NC transcription factors as potential markers of prognosis as well as targets for therapeutic intervention for neuroectodermal tumors.

Acknowledgements

Davis Anderson and Marianne Bronner Fraser (both of California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) provided thoughtful discussion.

Abbreviations

- NC

neural crest

- NT

neural tube

- MBL

medulloblastoma

- SPNET

supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor

- MNST

malignant nerve sheath tumor

- SHH

sonic hedgehog

Footnotes

The Division of Child Neurology, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons (New York, NY), and the Departments of Pediatrics and Neurology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY) provided crucial funding support.

References

- 1.Tassabehji M, Read AP, Newton VE, Harris R, Balling R, Gruss P, Strachan T. Waardenburg's syndrome patients have mutations in the human homologue of the Pax-3 paired box gene. Nature. 1992;355(6361):635–636. doi: 10.1038/355635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schorle H, Meier P, Buchert M, Jaenisch R, Mitchell PJ. Transcription factor AP-2 is essential for cranial closure and craniofacial development. Nature. 1996;381(6579):235–238. doi: 10.1038/381235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pingault V, Bondurand N, Kuhlbrodt K, Goerich DE, Prehu MO, Puliti A, Herbarth B, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Legius E, Matthijs G, et al. SOX10 mutations in patients with Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Nat Genet. 1998;18(2):171–173. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Southard-Smith EM, Kos L, Pavan WJ. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat Genet. 1998;18(1):60–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang D, Chen F, Milewski R, Li J, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Pax3 is required for enteric ganglia formation and functions with Sox10 to modulate expression of c-ret. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(8):963–971. doi: 10.1172/JCI10828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Douarin N, Kalcheim C. The Neural Crest. 2nd Ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goulding MD, Chalepakis G, Deutsch U, Erselius JR, Gruss P. Pax-3, a novel murine DNA binding protein expressed during early neurogenesis. EMBO J. 1991;10(5):1135–1147. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bang AG, Papalopulu N, Goulding MD, Kintner C. Expression of Pax-3 in the lateral neural plate is dependent on a Wnt-mediated signal from posterior nonaxial mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1999;212(2):366–380. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell PJ, Timmons PM, Hebert JM, Rigby PW, Tjian R. Transcription factor AP-2 is expressed in neural crest cell lineages during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5(1):105–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldi A, Santini D, Battista T, Dragonetti E, Ferranti G, Petitti T, Groeger AM, Angelini A, Rossiello R, Baldi F, et al. Expression of AP-2 transcription factor and of its downstream target genes c-kit, E-cadherin and p21 in humancutaneous melanoma. J Cell Biochem. 2001;83(3):364–372. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galibert MD, Yavuzer U, Dexter TJ, Goding CR. Pax3 and regulation of the melanocyte-specific tyrosinase-related protein-1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(38):26894–26900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollaaghababa R, Pavan WJ. The importance of having your SOX on: role of SOX10 in the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes and glia. Oncogene. 2003;22(20):3024–3034. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernasconi M, Remppis A, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher FJ, III, Schafer BW. Induction of apoptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells through down-regulation of PAX proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(23):13164–13169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholl FA, Kamarashev J, Murmann OV, Geertsen R, Dummer R, Schafer BW. PAX3 is expressed in human melanomas and contributes to tumor cell survival. Cancer Res. 2001;61(3):823–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borycki AG, Li J, Jin F, Emerson CP, Epstein JA. Pax3 functions in cell survival and in pax7 regulation. Development. 1999;126(8):1665–1674. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blake J, Ziman MR. PAX3 and PAX7 expression. A link to the metastatic potential of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and cutaneous malignant melanoma? Histol Histopathol. 2003;18(2):529–539. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansouri A. The role of Pax3 and Pax7 in development and cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 1998;9(2):141–149. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v9.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfisterer P, Ehlermann J, Hegen M, Schorle H. A subtractive gene expression screen suggests a role of transcription factor AP-2 alpha in control of proliferation and differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(8):6637–6644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng YX, Somasundaram K, el-Deiry WS. AP2 inhibits cancer cell growth and activates p21WAF1/CIP1 expression. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):78–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gee JM, Robertson JF, Ellis IO, Nicholson RI, Hurst HC. Immunohistochemical analysis reveals a tumour suppressor-like role for the transcription factor AP-2 in invasive breast cancer. J Pathol. 1999;189(4):514–520. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189:4<514::AID-PATH463>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershenwald JE, Sumner W, Calderone T, Wang Z, Huang S, Bar-Eli M. Dominant-negative transcription factor AP-2 augments SB-2 melanoma tumor growth in vivo. Oncogene. 2001;20(26):3363–3375. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellikainen J, Kataja V, Ropponen K, Kellokoski J, Pietilainen T, Bohm J, Eskelinen M, Kosma VM. Reduced nuclear expression of transcription factor AP-2 associates with aggressive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(11):3487–3495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paratore C, Goerich DE, Suter U, Wegner M, Sommer L. Survival and glial fate acquisition of neural crest cells are regulated by an interplay between the transcription factor Sox10 and extrinsic combinatorial signaling. Development. 2001;128(20):3949–3961. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Lo L, Dormand E, Anderson DJ. SOX10 maintains multipotency and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural crest stem cells. Neuron. 2003;38(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peirano RI, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Wegner M. Protein zero gene expression is regulated by the glial transcription factor Sox10. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(9):3198–3209. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3198-3209.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potterf SB, Furumura M, Dunn KJ, Arnheiter H, Pavan WJ. Transcription factor hierarchy in Waardenburg syndrome: regulation of MITF expression by SOX10 and PAX3. Hum Genet. 2000;107(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s004390000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbertson RJ, Perry RH, Kelly PJ, Pearson AD, Lunec J. Prognostic significance of HER2 and HER4 coexpression in childhood medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(15):3272–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayanil CS, George D, Mania-Farnell B, Bremer CL, McLone DG, Bremer EG. Overexpression of murine Pax3 increases NCAM polysialylation in a human medulloblastoma cell line. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(30):23259–23266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulte TW, Toretsky JA, Ress E, Helman L, Neckers LM. Expression of PAX3 in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors. Biochem Mol Med. 1997;60(2):121–126. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1997.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kho AT, Zhao Q, Cai Z, Butte AJ, Kim JY, Pomeroy SL, Rowitch DH, Kohane IS. Conserved mechanisms across development and tumorigenesis revealed by a mouse development perspective of human cancers. Genes Dev. 2004;18(6):629–640. doi: 10.1101/gad.1182504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alaminos M, Mora J, Cheung NK, Smith A, Qin J, Chen L, Gerald WL. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression associated with MYCN in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4538–4546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipinski M, Braham K, Philip I, Wiels J, Philip T, Goridis C, Lenoir GM, Tursz T. Neuroectoderm-associated antigens on Ewing's sarcoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1987;47(1):183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pomeroy SL, Tamayo P, Gaasenbeek M, Sturla LM, Angelo M, McLaughlin ME, Kim JY, Goumnerova LC, Black PM, Lau C, et al. Prediction of central nervous system embryonal tumour outcome based on gene expression. Nature. 415(6870):436–442. doi: 10.1038/415436a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Echelard Y, Epstein DJ, St-Jacques B, Shen L, Mohler J, McMahon JA, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity. Cell. 1993;75(7):1417–1430. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Rao PK, Wen R, Song Y, Muir D, Wallace P, van Horne SJ, Tennekoon GI, Kadesch T. Notch and Schwann cell transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23(5):1146–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy P, Vidaud D, Leroy K, Laurendeau I, Wechsler J, Bolasco G, Parfait B, Wolkenstein P, Vidaud M, Bieche I. Molecular profiling of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, based on large-scale real-time RT-PCR. Mol Cancer. 2004;3(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsokos M, Scarpa S, Ross RA, Triche TJ. Differentiation of human neuroblastoma recapitulates neural crest development: study of morphology, neurotransmitter enzymes and extracellular matrix proteins. Am J Pathol. 1987;128:484–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ambros IM, Zellner A, Roald B, Amann G, Ladenstein R, Printz D, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Role of ploidy, chromosome 1p, and Schwann cells in the maturation of neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(23):1505–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mora J, Cheung NK, Juan G, Illei P, Cheung I, Akram M, Chi S, Ladanyi M, Cordon-Cardo C, Gerald WL. Neuroblastic and schwannian stromal cells of neuroblastoma are derived from a tumoral progenitor cell. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6892–6898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart HJ, Brennan A, Rahman M, Zoidl G, Mitchell PJ, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Developmental regulation and overexpression of the transcription factor AP-2, a potential regulator of the timing of Schwann cell generation. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(2):363–372. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tucker RP. Neural crest cells: a model for invasive behavior. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118(3):277–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]