Abstract

The ArdA antirestriction protein of the IncB plasmid R16 selectively inhibited the restriction activity of EcoKI, leaving significant levels of modification activity under conditions in which restriction was almost completely prevented. The results are consistent with the hypothesis that ArdA functions in bacterial conjugation to allow an unmodified plasmid to evade restriction in the recipient bacterium and yet acquire cognate modification.

Classical restriction-modification (R-M) systems consist of a restriction endonuclease and a matching modification enzyme that methylates specific bases within the target or specificity site. Methylation of one or both strands of the specificity site protects the DNA from the cognate restriction enzyme. R-M systems are classified into three families according to enzyme composition and cofactor requirements, target sequence, and the location of the cleavage site relative to the target. Type I enzymes, typified by EcoKI, are hetero-oligomers of subunits encoded by the hsdR, hsdM, and hsdS genes (15). The main enzyme is a complex of subunits with a stoichiometry of R2M2S1, but there exists a second complex of M2S1 subunits which has methyltransferase but not endonuclease activity (9). Type I R-M enzymes cleave duplex DNA at various positions often remote from the target site. The cleavage process is thought to involve ATP- and S-adenosylmethionine-dependent binding to an unmodified specificity site followed by ATP-dependent translocation of DNA past the enzyme complex bound to the target sequence, with cleavage occurring when translocation is impeded by collision with an adjacent enzyme complex or some other protein or DNA structure (10, 18).

Type I R-M systems are prevalent and diverse in their specificities, as indicated by the presence of candidate genes in approximately half of the microbial genomes that have been fully sequenced and by the diversity of target sequences recognized by enzymes from closely related bacteria (12, 14). One ecological role of restriction systems is thought to be the destruction of infecting foreign DNA identified by the lack of cognate modification. Some bacteriophages and plasmids carry genes that alleviate the restriction of DNA by type I systems (16). The prototype of the plasmid antirestriction genes is the ardA locus of the IncI1 plasmid ColIbP-9 (8, 17). The ColIb ardA gene product functions in conjugation to alleviate the restriction of the transferring plasmid. Evidence for such a role includes the effect of mutation of ardA and coregulation of its expression with the plasmid transfer system (17); the location of ardA genes in the leading region, defined as the first portion of the plasmid to enter the recipient cell (7); and the transient induction of ardA in the conjugatively infected cell by a process thought to involve transcription of the transferring single strand of DNA (1, 4).

An appealingly simple hypothesis is that the ArdA system transiently blocks type I restriction systems in the conjugatively infected cell while allowing the immigrant plasmid to acquire protective modification as a prelude to its establishment as a symbiotic element. The hypothesis is inconsistent with reports that under conditions causing overproduction of the protein, ColIb ArdA inhibited the in vivo modification activity of EcoKI in addition to restriction (8, 17). Conserved ardA genes have been found in representatives of four other incompatibility groups (B, FV, K, and N) of enterobacterial plasmids (5, 7). We have reinvestigated the effects of ArdA on EcoKI by using the protein encoded by the IncB plasmid R16. ColIb and R16 are closely related plasmids, and the latter specifies an ArdA homologue that is predicted to be 93% identical at the amino acid sequence level with the ColIb equivalent and to have a similarly high net negative charge (7). Here we report that R16 ArdA selectively inhibited the restriction activity of EcoKI, leaving significant levels of methyltransferase activity under conditions in which restriction was almost completely prevented.

Does R16 ArdA inhibit the restriction and modification activities of EcoKI?

The assay was similar to that used elsewhere (8, 17) and involved virulent (vir) and clear-plaque (cI) mutants of phage λ to probe the R-M activities of EcoKI in strains containing or lacking R16 ArdA protein. The λcI ral18 strain provided by N. E. Murray was also used; the ral+ locus is an early gene that increases the efficiency of EcoKI as a de novo methyltransferase to promote efficient modification of DNA generated by the replication of infecting λ DNA molecules escaping restriction (13). ArdA production was determined by a pUC18 recombinant containing R16 ardA+ on a 2.2-kb PstI fragment (pLG2051) (7). The maintenance stability of the recombinant plasmid was maximized by adding methicillin (50 μg ml−1) to ampicillin (50 μg ml−1)-supplemented liquid media. Methicillin does not traverse the outer membrane of Escherichia coli and binds extracellular β-lactamase in an inactive complex.

E. coli K-12 strains included 5K (rK− mK+), C600 (rK+ mK+) (17), and a homogenic rK− mK+ derivative, NM816, with a point mutation in hsdR, provided by N. E. Murray. Strain NM710 lacks the defective prophage called Rac: this chromosomal locus, present in C600 and some other K-12 strains, contains lambdoid prophage sequences, including an inducible gene (lar) that is an analogue of λ ral (11).

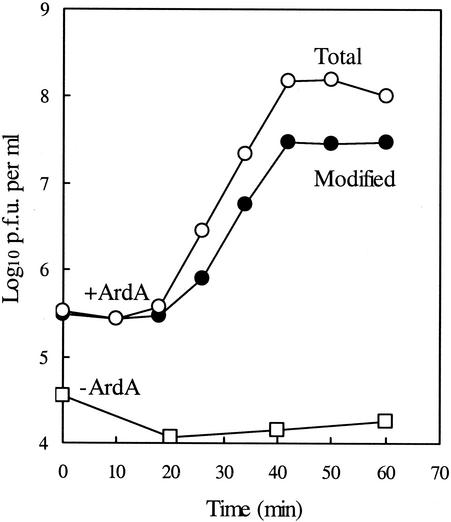

Figure 1 shows the effect of R16 ArdA specified by an overproducing recombinant on the de novo modification activity of EcoKI, as measured by the capacity of progeny phages from a λvir.0 (unmodified) infection of C600(pLG2051) to form plaques on C600 relative to the capacity of the phages to form plaques on 5K. It is noted that λ DNA contains five EcoKI sites which require methylation in at least one DNA strand to avoid the restriction response. The data (summarized in Table 1) show that at 60 min, 35% of the phages in a burst of 218 carried full EcoKI modification. Assuming that each of the five EcoKI sites is modified equally, this value equates to an 80% efficiency of modification at each site. In the absence of ArdA protein, total plaque-forming ability was reduced and no burst was observed. These results illustrate the effect of ArdA as a restriction alleviation protein and indicate that, while there is significant inhibition of modification, cells containing the overproduced R16 protein retain substantial levels of EcoKI methyltransferase activity. As shown in Table 1, significant levels of de novo modification of infecting λvir.0 also occurred in ArdA+ cells when the host strain was rK− mK+ (NM816) due to an hsdR mutation and when the Rac prophage was deleted (NM710). In the experiments with restricting hosts, Ard+ plasmid-containing cells supported almost complete alleviation of the restriction of incoming phages, as inferred from the efficiency-of-plating data (Table 1, column 3).

FIG. 1.

One-step growth of unmodified λvir on C600 (rK+ mK+) containing ArdA+ plasmid pLG2051. Bacteria from overnight cultures were grown in nutrient broth for three mass doublings to the mid-exponential phase of growth. Ampicillin (50 μg ml−1) and methicillin (50 μg ml−1) were added to select for stable carriage of Ard+ recombinant plasmids. Bacteria were sedimented and resuspended in buffer (6 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 10 mM MgSO4) to give ∼2 × 109 cells ml−1. Bacteriophages were added at a multiplicity of infection of 0.05. After 10 min of adsorption at room temperature, bacteria were sedimented and resuspended in nutrient broth at 2 × 107 cells ml−1. Samples were plated immediately (t = 0) with indicator bacteria to determine the number of PFU derived from infected cells and unadsorbed phages. At times thereafter, samples were treated with chloroform and plated with 5K indicator cells (○) to measure the total burst size and with C600 cells (•) to determine the number of EcoKI-modified phages. The number of PFU plating on 5K following infection of C600 lacking pLG2051 is also shown (ArdA−; □). Data are the means of results from two experiments.

TABLE 1.

De novo modification of λvir.0 during one cycle of growth in hosts containing the cloned ardA gene of R16a

| Host | Host genotype | EOPb on host | Burst size (no. of progeny phages/ infected cell) | % of burst modified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C600 | rK+ mK+ | 2.9 × 10−4 | NDc | ND |

| C600(pLG2051) | rK+ mK+ardA+ | 0.95 | 218 | 35 |

| NM816 | rK− mK+ | 1.00 | 33 | 82 |

| NM816(pLG2051) | rK− mK+ardA+ | 0.97 | 141 | 28 |

| NM710 | rK+ mK+ Δrac | 6.2 × 10−5 | ND | ND |

| NM710(pLG2051) | rK+ mK+ Δrac ardA+ | 0.78 | 110 | 22 |

The procedure was as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Samples were plated (t = 0) with indicator bacteria to determine the efficiency of plating, defined as the number of PFU produced on the C600 (r+ m+) indicator strain relative to the number produced on strain 5K (r− m+). Following a 60-min growth cycle, samples were treated with chloroform and plated with 5K indicator cells to measure the burst size and with C600 cells to determine the number of EcoKI-modified phages.

EOP, efficiency of plating.

ND, not determined.

The ArdA-overexpressing plasmid pLG2051 was likewise used to determine the effect of carrying the plasmid on the maintenance modification activity of EcoKI (Table 2). It is predicted from the burst sizes that some 2% or fewer of the progeny phages from a λ.K (modified) infection would retain modification were pLG2051 to cause complete inhibition of EcoKI methyltransferase activity. This fraction would represent those progeny containing one of the parental strands of the infecting modified phage genome. The results show that when the host strain was r− m+ (NM816) and carried the ArdA+ plasmid, approximately half of the progeny phages in the burst possessed EcoKI modification. The larger burst size detected in the plasmid-containing strain than that in NM816 is attributed to experimental variation and is thought to be biologically insignificant. To investigate whether Lar or Ral protein contributes to the retention of modification, tests were performed with a strain lacking the Rac prophage and a phage with a mutation in ral. The data indicate that neither the Rac prophage nor the ral gene of phage λ is responsible for the retention of EcoKI modification in the presence of R16 ArdA protein, although the effect of ral+ in enhancing modification can be seen. Overall, the results indicate that high in vivo levels of R16 ArdA preferentially inhibit the restriction activity of EcoKI rather than block R-M functions to the same extent.

TABLE 2.

Retention of modification by λ.K phages during one cycle of growth in hosts containing the cloned ardA gene of R16a

| Host | Host genotype | Input λ.K phage | EOPb on host | Burst size (no. of phages/ infected cell) | % of burst modified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM816 | rK− mK+ | λvir | 1.04 | 32 | 99 |

| NM816(pLG2051) | rK− mK+ardA+ | λvir | 1.05 | 127 | 53 |

| NM710 | rK+ mK+ Δrac | λvir | 0.98 | 96 | 98 |

| NM710(pLG2051) | rK+ mK+ Δrac ardA+ | λvir | 0.98 | 102 | 62 |

| NM710(pLG2051) | rK+ mK+ Δrac ardA+ | λcI ral+ | 0.97 | 90 | 21 |

| NM710(pLG2051) | rK+ mK+ Δrac ardA+ | λcI ral | 0.96 | 152 | 11 |

Experimental conditions were as described in footnote a of Table 1.

EOP, efficiency of plating.

Mode of action of ArdA.

Belogurov and Delver (6) identified a putative 14-residue antirestriction domain in the C-terminal portions of ColIb and pKM101 (IncN) ArdA proteins. The domain is also present in the ArdA proteins of R16 and F0lac (IncFV) and includes the invariant motif LL-D/E-E (6, 7). All of these proteins are highly acidic, with net negative charges ranging from −22 to −29 (7). The antirestriction domain was hypothesized to compete with a conserved motif in the HsdS polypeptide to interfere with the functional integrity of EcoKI as a restriction and modification enzyme (6), as indicated for the highly acidic Ocr antirestriction protein encoded by gene 0.3 of the virulent phage T7 (3). Recently, Ocr has been shown to be an elongated dimer that mimics the shape of bent DNA and acts as a substrate-analogue to bind EcoKI into an inactive complex (19). Multiple dimers bind strongly to EcoKI in an interaction that apparently involves the entire surface area of Ocr protein and leads to the wrapping of the EcoKI enzyme around the protein (2). Although ArdA shows no homology to Ocr, secondary structure predictions suggest similar structural features, including marked elongation and a series of negatively charged amphipathic helices that might mimic the DNA substrate (W. J. Brammar and B. M. Wilkins, unpublished data).

There is compelling evidence that ArdA functions in the conjugatively infected recipient cell to alleviate type I restriction of the immigrant plasmid (20). Our results are inconsistent with the generalization that ArdA proteins inactivate type I enzymes in that the R16 ArdA homologue showed specificity in targeting the restriction function of EcoKI, leaving significant levels of methyltransferase activity under conditions in which restriction was almost completely prevented. It is noted that our test for determining the fraction of modified phages probably underestimates the extent of EcoKI modification since all five target sites in λ DNA require methylation to produce the modified response.

There is no obvious explanation of the finding that R16 ArdA preferentially targeted the restriction activity of EcoKI but that the ColIb homologue blocked the restriction and modification activities of the enzyme. We have confirmed the latter response (unpublished data). The cloned plasmid sectors in the ArdA+ recombinants are alike in size, and the proteins have very similar compositions. The cloned ColIb ardA is grossly overexpressed relative to the gene in the native plasmid (1), raising the possibility that ArdA has nonphysiological effects on EcoKI modification dependent on the level of overexpression.

It is unknown how ArdA functions as an antirestriction protein. One possibility is that ArdA blocks a step specific for the restriction reaction, such as the DNA translocation or cleavage process. Alternatively, ArdA proteins might target the R2M2S1 form of the type I enzyme but not the M2S1 complex, which is active as a methyltransferase. Such hypotheses can be tested by purifying ArdA and using it in experiments in vitro.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 060852 from the Wellcome Trust.

We thank Noreen Murray for the gift of strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Althorpe, N. J., P. M. Chilley, A. T. Thomas, W. J. Brammar, and B. M. Wilkins. 1999. Transient transcriptional activation of the IncI1 plasmid anti-restriction gene (ardA) and SOS inhibition gene (psiB) early in conjugating recipient bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 31:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atanasiu, C., T. J. Su, S. S. Sturrock, and D. T. Dryden. 2002. Interaction of the ocr gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7 with EcoKI restriction/modification enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3936-3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandyopadhyay, P. K., F. W. Studier, D. L. Hamilton, and R. Yuan. 1985. Inhibition of the type I restriction-modification enzymes EcoB and EcoK by the gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7. J. Mol. Biol. 182:567-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates, S., R. A. Roscoe, N. J. Althorpe, W. J. Brammar, and B. M. Wilkins. 1999. Expression of leading region genes on IncI1 plasmid ColIbP-9: genetic evidence for single-stranded DNA transcription. Microbiology 145:2655-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belogurov, A. A., E. P. Delver, and O. V. Rodzevich. 1992. IncN plasmid pKM101 and IncI1 plasmid ColIb-P9 encode homologous antirestriction proteins in their leading regions. J. Bacteriol. 174:5079-5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belogurov, A. A., and E. P. Delver. 1995. A motif conserved among the type I restriction-modification enzymes and antirestriction proteins: a possible basis for mechanism of action of plasmid-encoded antirestriction functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:785-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chilley, P. M., and B. M. Wilkins. 1995. Distribution of the ardA family of antirestriction genes on conjugative plasmids. Microbiology 141:2157-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delver, E. P., V. U. Kotova, G. B. Zavilgelsky, and A. A. Belogurov. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of the gene (ard) encoding the antirestriction protein of plasmid ColIb-P9. J. Bacteriol. 173:5887-5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dryden, D. T. F., L. P. Cooper, and N. E. Murray. 1993. Purification and characterization of the methyltransferase from the type I restriction and modification system of Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13228-13236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janscak, P., M. P. MacWilliams, U. Sandmeier, V. Nagaraja, and T. A. Bickle. 1999. DNA translocation blockage, a general mechanism of cleavage site selection by type I restriction enzymes. EMBO J. 18:2638-2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King, G., and N. E. Murray. 1995. Restriction alleviation and modification enhancement by the Rac prophage of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 16:769-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong, H., L.-F. Lin, N. Porter, S. Stickel, D. Byrd, J. Posfai, and R. J. Roberts. 2000. Functional analysis of putative restriction-modification system genes in the Helicobacter pylori J99 genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3216-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loenen, W. A. M., and N. E. Murray. 1986. Modification enhancement by the restriction alleviation protein (Ral) of bacteriophage λ. J. Mol. Biol. 190:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milkman, R., E. A. Raleigh, M. McKane, D. Cryderman, P. Bilodeau, and K. McWeeny. 1999. Molecular evolution of the Escherichia coli chromosome. V. Recombination patterns among strains of diverse origin. Genetics 153:539-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray, N. E. 2000. Type I restriction systems: sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:412-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray, N. E. 2002. Immigration control of DNA in bacteria: self versus non-self. Microbiology 148:3-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Read, T. D., A. T. Thomas, and B. M. Wilkins. 1992. Evasion of type I and type II restriction systems by IncI1 plasmid ColIb-P9 during transfer by bacterial conjugation. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1933-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Studier, F. W., and P. K. Bandyopadhyay. 1988. Model for how type I restriction enzymes select cleavage sites in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:4677-4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walkinshaw, M. D., P. Taylor, S. S. Sturrock, C. Atanasiu, T. Berge, R. M. Henderson, J. M. Edwardson, and D. T. Dryden. 2002. Structure of Ocr from bacteriophage T7, a protein that mimics B-form DNA. Mol. Cell 9:187-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkins, B. M. 2002. Plasmid promiscuity: meeting the challenge of DNA immigration control. Environ. Microbiol. 4:495-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]