Abstract

Background:

White spotting patterns in mammals can be caused by mutations in the genes for the endothelin B receptor and c-Kit, whose protein products are necessary for proper migration, differentiation or survival of the melanoblast population of cells. Although there are many different dog breeds that segregate white spotting patterns, no genes have been identified that are linked to these phenotypes.

Results:

An intercross was generated from a female Newfoundland and a male Border Collie and the white spotting phenotypes of the intercross progeny were evaluated by measuring percentage surface area of white in the puppies. The Border Collie markings segregated as a simple autosomal recessive (7/25 intercross progeny had the phenotype). Two candidate genes, for the endothelin B receptor (EDNRB) and c-Kit (KIT), were evaluated for segregation with the white spotting pattern. Polymorphisms between the Border Collie and Newfoundland were identified for EDNRB using Southern analysis after a portion of the canine gene had been cloned. Polymorphisms for KIT were identified using a microsatellite developed from a bacterial artificial chromosome containing the canine gene.

Conclusions:

Both EDNRB and KIT were excluded as a cause of the white spotting pattern in at least two of the intercross progeny. Although these genes have been implicated in white spotting in other mammals, including horses, pigs, cows, mice and rats, they do not appear to be responsible for the white spotting pattern found in the Border Collie breed of dog.

Background

The genetics of coat color has been studied for many years in a variety of mammals, and the inheritance patterns of many of the relevant genes have been determined. Both scientists and breeders have studied the range of color and pattern that can be found in mammals. Dogs are uniquely suited for the investigation of the inheritance of coat color and patterns as the more than 200 different dog breeds are defined in part by a specific set of colors and patterns. 'White spotting' in mice, rats, dogs and horses is characterized by irregular white patches of skin and hair that are devoid of pigment-producing melanocytes. White spotting in domestic dog breeds has been postulated to be controlled by one locus, called s, which has at least three alleles [1]. The three alleles segregate in some breeds, while other breeds are homozygous and show a standard spotting pattern. Although the variation in coat colors and patterns in dogs is far greater than in other species, the genes responsible for coat color in dogs have yet to be identified at the molecular level, with the exception of that for the yellow coat color [2].

Genes responsible for white spotting in mice and horses and for hypopigmentation defects in humans have been identified. One of these, EDNRB, encoding the endothelin B receptor, causes white spotting in the Ednrb mouse [3]. Some alleles of Ednrb are associated with more severe defects, such as deafness and aganglionic megacolon. Mutations in the endothelin B receptor gene are also responsible for Hirshsprung disease in humans [4]. This disease is characterized by intestinal aganglionosis, which is occasionally associated with hypopigmentation and/or deafness. A similar syndrome in horses, called lethal white foal syndrome, is due to a mutation in the horse endothelin B receptor gene [5,6,7].

Mutations in a second gene, cKIT, which encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase, cause the piebald trait in humans [8]. Piebaldism is characterized by white patches on skin and hair. In horses, a similar phenotype, called Tobiano, is caused by a mutation in either KIT or a closely linked gene [9]. A duplication of KIT causes white spotting in pigs [10]. EDNRB and KIT are therefore two likely candidates for white spotting in dogs.

Results and discussion

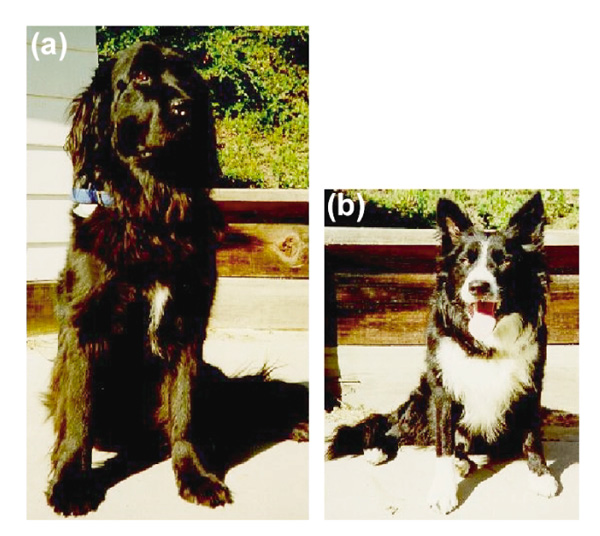

As a resource for building a dog genetic map and as a tool to study the genes responsible for behavioral and morphological differences in the dog, an intercross was created between a male Border Collie and a female Newfoundland. The Newfoundland parent had a small patch of white on the chest and was otherwise completely black (Figure 1a). The Border Collie used in this cross had markings characteristic for the breed - black with white markings on the face, chest, neck, tail tip, ventral abdomen, all four digits, and extending up the front legs to the carpals (Figure 1b). These markings have many similarities to the white spotting patterns of other mammals. The Border Collie's sire and dam had the same markings, consistent with homozygosity for the causative loci. This cross provides the opportunity for analyzing the inheritance of the white spotting pattern exhibited by the Border Collie. Six F1 animals were produced which had medium-sized white patches on their chests. These six dogs were intercrossed to produce 25 F2 progeny. In the F2 generation, 7/25 had markings like the Border Collie parent, consistent with the phenotype being caused by a recessive allele of a single locus.

Figure 1.

A Newfoundland female (a) was bred to a Border Collie male (b) to produce animals for the intercross.

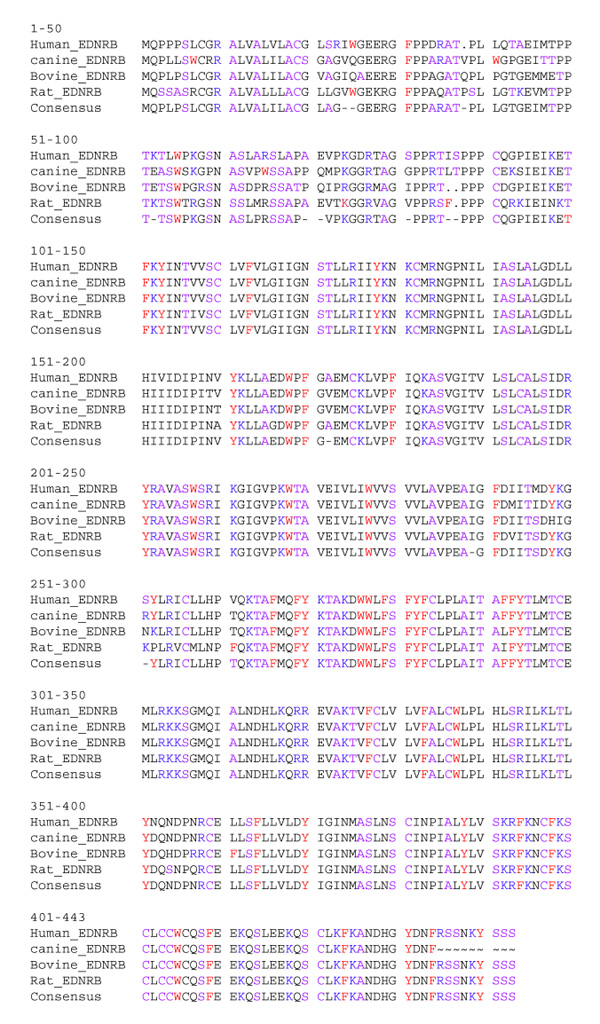

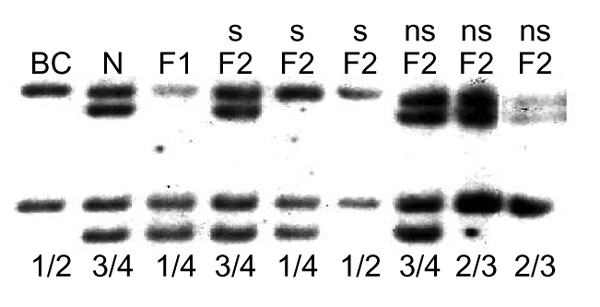

To determine if EDNRB was responsible for the white spotting pattern of the Border Collie, a portion of canine cDNA was cloned. The amino-acid sequence of canine endothelin B receptor was highly homologous to that of other mammalian endothelin B receptors (Figure 2). The canine cDNA clone was used as a hybridization probe for DNA hybridization blot experiments. A PvuII restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) was identified between the Border Collie grandparent and the Newfoundland grandparent of the cross. Spotted F2 progeny carried at least one allele of this polymorphism that was different from those carried by the Border Collie parent, indicating that this locus was not linked to white spotting pattern in this cross (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Amino-acid sequence alignment of mammalian endothelin B receptors using the 'pretty' function from the GCG Wisconsin package. Accession numbers for sequences used for comparison: bovine EDNRB, S63513; human EDNRB, JQ1042; rat EDNRB, I57950; canine EDNRB, AF276427.

Figure 3.

Segregation of EDNRB compared with the segregation of the white spotting phenotype. Genomic DNA digested with PvuII was probed with a radioactively labeled fragment of EDNRB DNA which detected a PvuII restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) between the Border Collie and Newfoundland grandparents. BC, DNA from the Border Collie grandparent; N, DNA from the Newfoundland grandparent. F1, DNA from the first generation hybrids of the Newfoundland × Border Collie cross; F2, DNA from the progeny of intercrosses between the F1 hybrids; s, white spotted; ns, not white spotted. The presumed genotypes for the EDNRB locus are shown below the lanes.

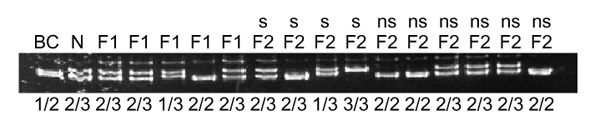

To evaluate the segregation of the second candidate for white spotting, KIT, in this cross, a polymorphic simple-sequence repeat was developed from bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones containing the KIT gene. Three of the four BACs containing the KIT gene also contained this simple-sequence repeat, as ascertained by PCR amplification of a product from the BACs using primers flanking the simple-sequence repeat. In addition, positive PCR amplification of a product using both KIT genomic primers and the simple-sequence repeat primers occurred in the same subset of radiation hybrid cell lines from a dog/hamster panel from Research Genetics, Inc. (Alabama, USA). This simple-sequence repeat marker was polymorphic in the intercross and segregated independent of the white spotting phenotype (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Segregation of KIT compared with segregation of the white spotting phenotype. Segregation of KIT was followed by detection of a simple-sequence repeat polymorphic difference between the Newfoundland and Border Collie grandparents. BC, DNA from the Border Collie grandparent; N, DNA from the Newfoundland grandparent; F1, DNA from the first generation hybrids; F2, DNA from the second generation intercrosses. s, white spotted; ns, not white spotted. The presumed genotypes for the KIT locus are shown below the lanes.

By analogy with mice and humans, mutations in both EDNRB and KIT were excellent candidates for white spotting in Border Collies; however, these data taken together excluded both genes from being responsible for the distinctive Border Collie coat color markings. Although it has been postulated that all white spotting in dogs is due to the same major locus, allelism tests between the spotting phenotypes in all the different dog breeds have not been performed. It is possible that either EDNRB or KIT could be responsible for white spotting in other breeds. Extreme white spotting, an additional allele of the s locus, segregates in the Boxer breed. The markers developed in this study were not polymorphic in available individuals of this breed, so we were unable to test for linkage to this presumptive allele of the s locus. As more genes are placed on the canine genetic map, it will be possible to test other candidates for white spotting derived from studies of coat color genetics in mice. White markings are often associated with deafness in dogs, cats, and even humans. They can also be associated with aganglionic megacolon in humans and horses. The link between white spotting and lack of innervation to the distal colon is the neural crest, from which melanocytes and enteric ganglia are both derived. The exclusion of EDNRB as a candidate gene for white spotting in Border Collies may explain why aganglionic megacolon is not associated with this trait in dogs. The gene responsible for white spotting in dogs may shed light on new genes involved in the differentiation and survival of the neural crest.

Materials and methods

A female Newfoundland dog was bred to a male Border Collie. All dogs were placed in people's homes as pets. Blood was drawn for DNA extraction and photographs were taken of the dogs. F1 progeny from this cross were intercrossed to produce 25 F2 progeny. Seven of those 25 F2 progeny had white markings similar to the Border Collie parent. To evaluate the white spotting, the percentage of white based on surface area was compared between parents, F1 and F2 progeny. Photographs of the dogs were taken and the weight of the white markings in the image was compared to the total weight of the dog image after cutting, on a percent basis.

A portion of the EDNRB cDNA was cloned as a 1,314 bp product using the tri-clone kit (Invitrogen Corp., California, USA) using primers designed from mouse and human sequences (E1(ATG)F 5'-CAG GTA GCA GCA TGC AGC-3' and E3 5'-GGA ACG GAA GTT GTC ATA TCC-3'). The clone was sequenced (GenBank AF276427) and the deduced amino-acid sequence was compared to that of the published mammalian sequences using the 'pretty' program (GCG Wisconsin Package; Genetics Computer Group, Wisconsin, USA). The 1,314 bp fragment was radioactively labeled and used as a hybridization probe against genomic DNA digested with PvuII. Segregation of EDNRB was followed in the intercross progeny by this PvuII RFLP (Figure 3).

To follow segregation of KIT in this pedigree, a simple-sequence repeat in close proximity to KIT was isolated. A portion of KIT was cloned by PCR using published primers [11] and used to screen a canine BAC library (BAC-PAC Resources, BACPAC Resource Center at the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, California, USA). A GAAA (18) repeat microsatellite marker was developed from one of the BACs (KIT forward 5'-GCA TGG AGC CTG CTT CTC-3', KIT reverse 5'-AGA GCA TCC TTG GTC TGT CC-3'). PCR amplification of the simple-sequence repeat from the intercross animals is shown in Figure 4. PCR amplification products of the KIT microsatellite were separated by electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide before photography.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Neff, Sara Okamura, Ashild Vik and Michael Bannasch for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by a gift from Martin and Enid Gleich and by the Richard and Rhoda E. Goldman Foundation.

References

- Little CB. The Inheritance of Coat Color in Dogs. New York: Howell Book House. 1957.

- Newton JM, Wilkie AL, He L, Jordan SA, Metallinos DL, Holmes NG, Jackson IJ, Barsh GS. Melanocortin I receptor variation in the domestic dog. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s003350010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda K, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Baynash AG, Cheung JC, Giaid A, Yanagisawa M. Targeted and natural (piebald-lethal) mutations of endothelin-B receptor gene produce mega-colon associated with spotted coat color in mice. Cell. 1994;79:1267–1276. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffenberger EG, Hosoda K, Washington SS, Nakao K, deWitD , Yanagisawa M, Chakravart A. A missense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in multigenic Hirschsprung's disease. Cell. 1994;79:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallinos DL, Bowling AT, Rine J. A missense mutation in the endothelin-B receptor gene is associated with lethal white foal syndrome: an equine version of Hirschsprung disease. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:426–431. doi: 10.1007/s003359900790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santschi EM, Purdy AK, Valberg SJ, Vrotsos PD, Kaese H, Mickelson JR. Endothelin receptor B polymorphism associated with lethal white foal syndrome in horses. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:306–309. doi: 10.1007/s003359900754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GC, Croaker D, Zhang AL, Manglick P, Cartmill T, Cass D. A dinucleotide mutation in the endothelin-B receptor gene is associated with lethal white foal syndrome (LWFS), a horse variant of Hirschsprung disease. Hum Mol Gen. 1998;7:1047–1052. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudsepp T, Kijas J, Godard S, Guerin G, Andersson L, Chowdhary BP. Comparison of horse chromosome 3 with donkey and human chromosomes by cross-species painting and heterologous FISH mapping. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s003359900986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezoe K, Holmes SA, Ho L, Bennett CP, Bolognia JL, Brueton L, Burn J, Falabella R, Gatto EM, Ishii N, et al. Novel mutations and deletions of the KIT (steel factor receptor) gene in human piebaldism. . Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:58–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson Moller M, Chaudhary R, Hellmén E, Höyheim B, Chowdhary B, Andersson L. Pigs with the dominant white coat color phenotype carry a duplication of the KIT gene encoding the mast/stem cell growth factor receptor. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:822–830. doi: 10.1007/s003359900244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London CA, Kisseberth WC, Galli SJ, Geissler EN, Helfand SC. Expression of stem cell factor receptor (c-kit) by the malignant mast cells from spontaneous canine mast cell tumours. J Comp Pathol . 1996;115:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(96)80074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]