Abstract

Disease resistance in Arabidopsis is regulated by multiple signal transduction pathways in which salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) function as key signaling molecules. Epistasis analyses were performed between mutants that disrupt these pathways (npr1, eds5, ein2, and jar1) and mutants that constitutively activate these pathways (cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6), allowing exploration of the relationship between the SA- and JA/ET–mediated resistance responses. Two important findings were made. First, the constitutive disease resistance exhibited by cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6 is completely suppressed by the SA-deficient eds5 mutant but is only partially affected by the SA-insensitive npr1 mutant. Moreover, eds5 suppresses the SA-accumulating phenotype of the cpr mutants, whereas npr1 enhances it. These data indicate the existence of an SA-mediated, NPR1-independent resistance response. Second, the ET-insensitive mutation ein2 and the JA-insensitive mutation jar1 suppress the NPR1-independent resistance response exhibited by cpr5 and cpr6. Furthermore, ein2 potentiates SA accumulation in cpr5 and cpr5 npr1 while dampening SA accumulation in cpr6 and cpr6 npr1. These latter results indicate that cpr5 and cpr6 regulate resistance through distinct pathways and that SA-mediated, NPR1-independent resistance works in combination with components of the JA/ET–mediated response pathways.

INTRODUCTION

In plants, resistance to pathogen infection is accomplished through protective physical barriers and a diverse array of antimicrobial chemicals and proteins. Many of these antimicrobial compounds are part of an active defense response, and their rapid induction is contingent on the plant's ability to recognize and respond to an invading pathogen (Staskawicz et al., 1995; Baker et al., 1997). Pathogen recognition often involves the interaction of an avirulence signal (encoded by pathogen avr genes) and cognate plant resistance gene (R) products (Staskawicz et al., 1995; Bent, 1996; Baker et al., 1997). The avr/R interaction often triggers a strong defense mechanism known as the hypersensitive response (HR) (Flor, 1947, 1971; Keen, 1990; Van Der Biezen and Jones, 1998). In general, pathogens that activate avr/R–mediated signaling pathways do not cause disease and are said to be avirulent.

An HR activated by avr/R signaling is characterized by several physiological changes, including the accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates, nitric oxide, and salicylic acid (SA) (Dangl et al., 1996; Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996; Low and Merida, 1996; Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Delledonne et al., 1998; Durner et al., 1998). Jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) are also produced in response to pathogen infection, most probably because of an increase in lipoxygenase and 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) oxidase activities, respectively (Gundlach et al., 1992; Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Penninckx et al., 1996; Thomma et al., 1998). SA, JA, and ET induce the production of antimicrobial compounds such as phytoalexins and pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins (Lamb and Dixon, 1997). Ultimately, the HR results in the death of the infected cells and the containment of the pathogen (Dangl et al., 1996). Interestingly, recent studies have shown that cell death is neither necessary nor sufficient for the containment of avirulent pathogens (Bendahmane et al., 1999; Dinesh-Kumar and Baker, 1999).

As a consequence of an HR, a systemic signal is released from the point of infection that induces a secondary resistance response, known as systemic acquired resistance (SAR; Uknes et al., 1993; Ryals et al., 1994, 1996; Sticher et al., 1997). SAR is characterized by an increase in endogenous SA, transcriptional activation of the PR genes (PR-1, BGL2 [PR-2], and PR-5), and enhanced resistance to a broad spectrum of virulent pathogens. SA is a necessary and sufficient signal for SAR because removing SA through the ectopic expression of salicylate hydroxylase (encoded by the bacterial nahG gene) blocks the onset of SAR (Gaffney et al., 1993), whereas increasing SA concentrations by endogenous synthesis or exogenous application induces SAR (White, 1979; Malamy et al., 1990, 1992; Métraux et al., 1990; Rasmussen et al., 1991; Yalpani et al., 1991; Enyedi et al., 1992). Synthetic SA analogs such as 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid (INA) and benzothiodiazole are also effective inducers of SAR (Métraux et al., 1991; Görlach et al., 1996). Moreover, transgenic plants expressing nahG are defective in containing avirulent pathogens, indicating that SA also plays a role in the HR (Delaney et al., 1994).

Numerous Arabidopsis defense-related mutants have been isolated and analyzed in an effort to dissect inducible plant defense responses (Dong, 1998; Glazebrook et al., 1997). Among them, only npr1 (also known as nim1), which exhibits enhanced susceptibility to a wide range of bacterial and fungal pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola ES4326 and Peronospora parasitica Noco2, was found to be SA insensitive (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995; Glazebrook et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1997). All 12 alleles of the npr1 locus are hypersusceptible to pathogen infection, even after induction by SA or INA. eds5 is another mutant with enhanced disease susceptibility. But unlike npr1, eds5 is defective in SA synthesis rather than SA signaling, and the mutant phenotype can be rescued by the addition of SA (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999).

In contrast to loss-of-resistance mutants such as npr1 and eds5, cpr mutants exhibit increased concentrations of SA, constitutive expression of the PR genes, and enhanced resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2 (Bowling et al., 1994, 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). The cpr1 and cpr5 mutations are recessive; the cpr6 mutation is dominant. In addition, the cpr5 mutant forms spontaneous HR-like lesions and has impaired trichome development (Bowling et al., 1997; Boch et al., 1998).

When npr1 was crossed into a cpr5 or cpr6 background, resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 was blocked. Surprisingly, however, resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 was unaffected by the npr1 mutation, indicating that an NPR1-independent pathway is activated in these cpr mutants. Consistent with this latter observation, the antifungal genes PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 are constitutively expressed in cpr5 and cpr6 as well as in the cpr5 npr1 and cpr6 npr1 double mutants (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). Because PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 are known to be regulated by JA and ET (Epple et al., 1995; Penninckx et al., 1996), results from the study of cpr5 npr1 and cpr6 npr1 double mutants suggested that JA and ET may function in this NPR1-independent pathway.

The JA/ET dependency of the expression of PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 was demonstrated by the use of the ET-insensitive mutants etr1 and ein2 (Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990) and the JA-insensitive mutants coi1 and jar1 (Staswick et al., 1992; Feys et al., 1994). These mutants suppress the induction of PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 by biological or chemical stimuli (Epple et al., 1995; Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998). Aside from regulating the expression of PDF1.2 and Thi2.1, JA and ET have been shown to be involved in induced systemic resistance, which is activated by the nonpathogenic root-colonizing bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens (Pieterse et al., 1996). Induced systemic resistance is independent of SA, does not involve expression of PR-1, PR-2, or PR-5, and is blocked in etr1, ein2, coi1, and jar1 mutants (Pieterse et al., 1996, 1998). Further evidence that JA plays an important role in plant defense was provided by the observation that methyl jasmonate induces resistance in Arabidopsis to Alternaria brassicicola and Botrytis cinerea and that this induced resistance is blocked in the coi1 mutant (Thomma et al., 1998). Moreover, Arabidopsis and tobacco mutants that are insensitive to JA and ET, respectively, exhibit susceptibility to various strains of the nonhost pathogen Pythuim (Knoester et al., 1998; Staswick et al., 1998; Vijayan et al., 1998). Furthermore, mutants that are insensitive to ET acquire greater susceptibility to B. cinerea in Arabidopsis and reduced HR resistance to some avirulent pathogens in soybean (Hoffman et al., 1999; Thomma et al., 1999).

In addition to the observation that cpr npr1 double mutants are resistant to P. parasitica Noco2 (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998), several studies have indicated the existence of NPR1-independent resistance pathways (Reuber et al., 1998; Rate et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1999). For example, ssi1 (Shah et al., 1999) and acd6 (Rate et al., 1999) are dominant, lesion-forming mutants that express PR genes constitutively. In an npr1 background, both mutants still exhibit a considerable amount of PR gene expression and pathogen resistance; when crossed into a nahG background, however, all of these defense-related phenotypes, including the lesion-forming phenotype, are suppressed. These results suggest that the NPR1-independent responses observed in ssi1 and acd6 are SA dependent. On the other hand, because the lesion-forming phenotypes of ssi1 and acd6 are also SA dependent, it has been difficult to determine whether the NPR1-independent resistance observed in ssi1 and acd6 is induced directly by SA or indirectly through the formation of lesions. Lesioning can stimulate the expression of PDF1.2 (Pieterse and van Loon, 1999), presumably by the activation of a JA/ET–mediated pathway.

Here, we report the results of a comprehensive epistasis analysis designed to explore the NPR1-independent pathways induced in the cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6 mutants. In a two-pronged effort, we used the SA-deficient eds5 and the JA/ET–insensitive ein2 and jar1 mutants in double- and triple-mutant combinations with npr1, cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6. Our results indicate that bypassing the npr1 mutation requires high amounts of SA plus an unidentified elicitor derived from the plant host, the pathogen, or both. We speculate that this defense mechanism may resemble the local resistance response initiated during an HR. We also show that components of the JA/ET–mediated resistance pathway are required for SA-mediated, NPR1-independent resistance. These results show that SA and JA/ET function together in the cpr mutants to confer resistance.

RESULTS

We have previously shown that cpr5 and cpr6 constitutively express both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent defense responses (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). To better evaluate the contribution of SA and JA/ET toward NPR1-independent resistance, we performed a comprehensive epistasis analysis designed to identify and isolate the resistance pathways induced in the cpr mutants. The results pertaining to SA-mediated resistance are presented first.

Generation of the cpr eds5 Double Mutants

To determine whether the NPR1-independent resistance observed in the cpr mutants is SA dependent, we generated cpr eds5 double mutants. eds5 is an SA-deficient mutant, and the mutant phenotypes are rescued by treatment with SA (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). As detailed in Methods, the following double mutants were constructed: cpr1 eds5 (c1e5), cpr5 eds5 (c5e5), and cpr6 eds5 (c6e5).

Morphologically, the cpr eds5 double mutants resemble the cpr parents with only minor differences. As detailed in our previous publications, all three cpr parents are smaller than those of the wild type, with cpr5 also showing spontaneous lesions and compromised trichome development (Bowling et al., 1994, 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). In the c5e5 double mutant, the spontaneous lesions are not as pervasive as those found in the cpr5 single mutant. An examination of the lesion phenotype with trypan blue stain (Bowling et al., 1997) revealed that even though lesions develop 4 to 7 days later in c5e5 than in cpr5, both microscopic and macroscopic lesions are present in the double mutant (data not shown).

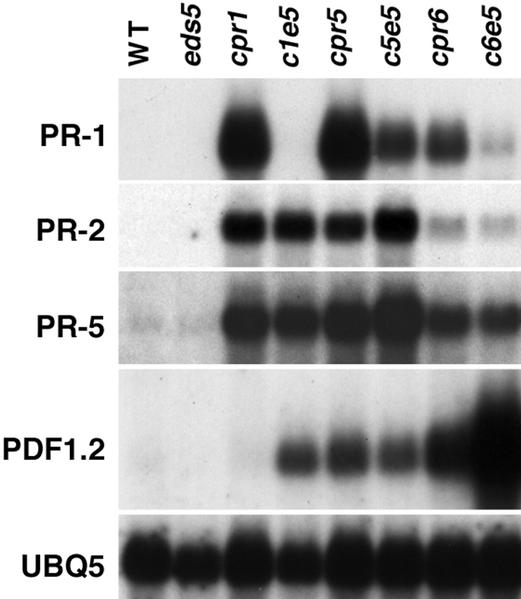

An RNA gel blot analysis was performed to determine how eds5 affects the expression of the PR genes in the cpr mutants. As shown in Figure 1, PR-1 gene expression was markedly decreased in c1e5 and c6e5, and less so in c5e5. On the other hand, the eds5 mutation had little effect on PR-2 or PR-5 gene expression in any of the cpr eds5 double mutants. The double mutants were also assayed for PDF1.2 expression to determine whether eds5 influences the expression of the JA/ET–mediated genes in the cpr mutants. We found that although PDF1.2 expression was not affected by eds5 in the c5e5 double mutant, there was a substantial increase in PDF1.2 mRNA accumulation in c1e5 and c6e5. Given the variety of experiments that have shown that the SA and JA/ET pathways can function antagonistically, we attribute the increased expression of PDF1.2 in the c1e5 and c6e5 double mutants to the lack of SA signaling in eds5 (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 1998; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999; Shah et al., 1999). The fact that such an increase is not observed in c5e5 suggests that PDF1.2 expression in cpr5 is lesion dependent. Similar results were found with plants grown under different conditions and collected at different times during development (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effects of eds5 on PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, and PDF1.2 Gene Expression in the cpr Mutants.

PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, and PDF1.2 gene-specific probes were used for RNA gel blot analysis of the indicated genotypes. The UBQ5 transcript was used as a loading standard. RNA was extracted from 3-week-old soil-grown plants. RNA gel blot analysis was performed at both Duke and Massachusetts General Hospital with similar results. c1e5, cpr1 eds5; c5e5, cpr5 eds5; c6e5, cpr6 eds5; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

Resistance Analysis of the cpr eds5 Double Mutants

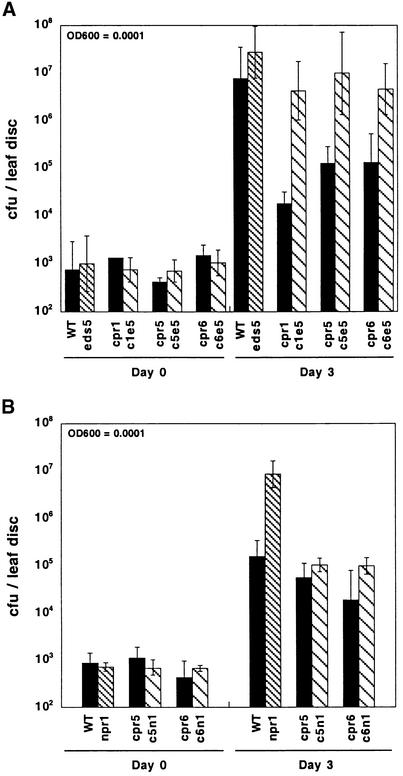

To examine the effect of eds5 on pathogen resistance in the cpr mutants, we inoculated the cpr eds5 double mutants with subclinical doses of P. s. maculicola ES4326 ( ) (Glazebrook et al., 1996). At this level of inoculum, wild-type plants show various degrees of responses, as shown in Figures 2A and 2B. In contrast, the cpr mutants always exhibit resistance, and eds5 and npr1 consistently develop severe disease symptoms. As shown in Figure 2A, c1e5, c5e5, and c6e5 were all susceptible to P. s. maculicola ES4326, whereas all three cpr mutants were resistant, indicating that eds5 suppressed the resistance conferred by the cpr mutations. The addition of INA to the cpr eds5 double mutants reestablished resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 (data not shown). We also included as controls in the infection experiment the cpr npr1 double mutants. In contrast to the complete suppression of resistance by eds5, npr1 seemed to diminish resistance only slightly in the cpr npr1 double mutants (Figure 2B). This latter result appears to be inconsistent with data reported in our previous publications (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998), which had indicated that npr1 completely suppressed resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326. We attribute this discrepancy to the fact that a 10-fold greater bacterial inoculum was used in the previous study. The observation that the cpr npr1 double mutants are susceptible to P. s. maculicola ES4326 at a greater inoculum but resistant to the same pathogen at the lower inoculum suggests that this NPR1-independent resistance observed in cpr mutants can be overcome by a higher titer of the pathogen.

) (Glazebrook et al., 1996). At this level of inoculum, wild-type plants show various degrees of responses, as shown in Figures 2A and 2B. In contrast, the cpr mutants always exhibit resistance, and eds5 and npr1 consistently develop severe disease symptoms. As shown in Figure 2A, c1e5, c5e5, and c6e5 were all susceptible to P. s. maculicola ES4326, whereas all three cpr mutants were resistant, indicating that eds5 suppressed the resistance conferred by the cpr mutations. The addition of INA to the cpr eds5 double mutants reestablished resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 (data not shown). We also included as controls in the infection experiment the cpr npr1 double mutants. In contrast to the complete suppression of resistance by eds5, npr1 seemed to diminish resistance only slightly in the cpr npr1 double mutants (Figure 2B). This latter result appears to be inconsistent with data reported in our previous publications (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998), which had indicated that npr1 completely suppressed resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326. We attribute this discrepancy to the fact that a 10-fold greater bacterial inoculum was used in the previous study. The observation that the cpr npr1 double mutants are susceptible to P. s. maculicola ES4326 at a greater inoculum but resistant to the same pathogen at the lower inoculum suggests that this NPR1-independent resistance observed in cpr mutants can be overcome by a higher titer of the pathogen.

Figure 2.

Effects of eds5 and npr1 on the Growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326 in the cpr Mutants.

(A) Growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326 on the cpr eds5 double mutants compared with that on the cpr mutants.

(B) Growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326 on the cpr npr1 double mutants compared with that on the cpr mutants.

Plants were infected by infiltrating a suspension of P. s. maculicola ES4326 in 10 mM MgCl2, corresponding to an OD600 of 0.0001. Leaf discs were collected immediately after infection (day 0) and 3 days later. Four samples from each genotype were collected on day 0; six samples from each genotype were collected on day 3. The cpr1 npr1 double mutant was not tested because of its prohibitively small size. The results obtained in this experiment are different from those reported previously (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998) because we used 10-fold less bacterial inoculum in the experiments reported here. Although this low bacterial inoculum produced consistent results in distinguishing the resistant mutants from the susceptible ones, the growth of the pathogen varied significantly in wild-type plants. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits of log-transformed data (Sokal and Rohlf, 1981). Growth analysis of P. s. maculicola ES4326 in the cpr eds5 mutants was performed at both Duke and Massachusetts General Hospital with similar results. cfu, colony-forming unit; c1e5, cpr1 eds5; c5e5, cpr5 eds5; c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c6e5, cpr6 eds5; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

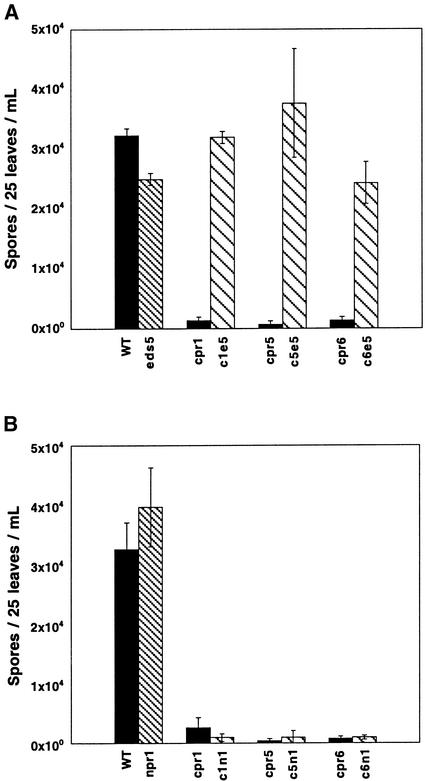

The cpr eds5 double mutants were also tested for resistance to the virulent oomycete pathogen P. parasitica Noco2. As shown in Figure 3, we found that all three cpr eds5 double mutants were susceptible to P. parasitica Noco2 infection at an inoculum of 3 × 104 spores mL−1 and that treatment with INA restored resistance in these double mutants (data not shown). In contrast, cpr1 npr1 (c1n1), cpr5 npr1 (c5n1), and cpr6 npr1 (c6n1) still maintained resistance to P. parasitica Noco2, which is consistent with our previous findings (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). To determine whether the NPR1-independent resistance could be overcome with a greater inoculum of P. parasitica Noco2, as is the case for resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326, we infected the cpr npr1 double mutants with a spore suspension of 4 × 106 spores mL−1. At this inoculum, we indeed observed a slight loss of resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 in the cpr npr1 double mutants (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of eds5 and npr1 on Resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 in the cpr Mutants.

(A) Growth of P. parasitica Noco2 on the cpr eds5 double mutants compared with that on the cpr mutants.

(B) Growth of P. parasitica Noco2 on the cpr npr1 double mutants compared with that on the cpr mutants.

P. parasitica Noco2 infection was accomplished by spraying a conidiospore suspension (3 × 104 spores mL−1) onto 2-week-old plants and assaying for pathogen growth 7 days later. The infection was quantified using a hemacytometer to count the number of spores in a 10-μL aliquot of spores harvested from 25 leaves in 1 mL of water. Two independent counts from each sample were averaged. The averages from three independent samples were used to compute the number of spores per 25 leaves per milliliter (±sd). c1e5, cpr1 eds5; c1n1, cpr1 npr1; c5e5, cpr5 eds5; c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c6e5, cpr6 eds5; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

The resistance profile for each of the single and double mutants is summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary of Resistance Phenotypes of the Parental Mutantsa

| Genotype | P. s. maculicola ES4326b | P. parasitica Noco2c |

|---|---|---|

| Col | S | S |

| cpr1 | R | R |

| cpr5 | R | R |

| cpr6 | R | R |

| npr1 | S | S |

| eds5 | S | S |

| nahG | S | S |

| ein2 | S | S |

| jar1 | S | S |

R, resistance; S, susceptible.

OD600 = 0.0001.

104 spores mL−1.

Table 2.

Summary of the Resistance Phenotypes of Double and Triple Mutantsa

| Genotype | P. s. maculicola ES4326b | P. parasitica Noco2c |

|---|---|---|

| cpr1 npr1 | —d | R |

| cpr5 npr1 | Re | R |

| cpr6 npr1 | Re | R |

| cpr1 eds5 | S | S |

| cpr5 eds5 | S | S |

| cpr6 eds5 | S | S |

| npr1 eds5 | S | S |

| eds5 nahG | S | S |

| cpr1 nahG | S | S |

| cpr5 nahG | S | S |

| cpr6 nahG | S | S |

| cpr5 ein2 | R | R |

| cpr5 jar1 | R | R |

| cpr5 npr1 ein2 | S | S |

| cpr5 npr1 jar1 | S | S |

| cpr6 ein2 | R | S |

| cpr6 jar1 | R | S |

| cpr6 npr1 ein2 | S | S |

| cpr6 npr1 jar1 | S | S |

| npr1 ein2 | S | S |

| npr1 jar1 | S | S |

| ein2 jar1 | S | S |

| npr1 ein2 jar1 | S | S |

R, resistance; S, susceptible.

OD600 = 0.0001.

104 spores mL−1.

Plants were too small to test.

Susceptible at an OD600 = 0.001. (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998).

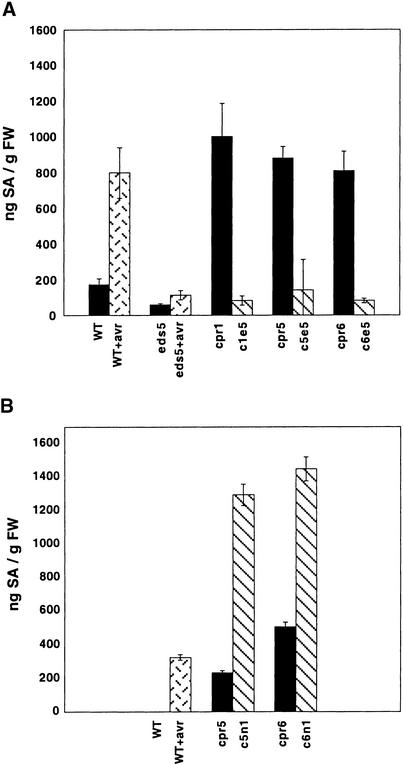

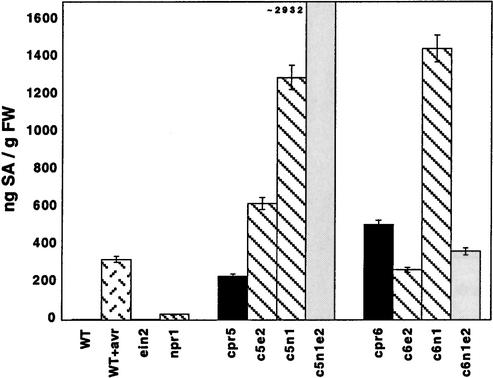

SA Accumulation in the cpr eds5 Double Mutants

As shown in Figure 4A, the increased SA accumulations reported previously in the cpr mutants (Bowling et al., 1994, 1997; Clarke et al., 1998) are suppressed in c1e5, c5e5, and c6e5. Similar to the result of Nawrath and Métraux (1999), we also observed that eds5 suppressed the accumulation of SA in response to an avirulent pathogen (P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2) (Figure 4A). In contrast, as shown in Figure 4B, npr1 did not suppress SA synthesis in the cpr mutants. Rather, npr1 further increased the concentrations of SA in the cpr npr1 double mutants over those found in the cpr single mutants, suggesting that npr1 is defective in feedback regulation of SA accumulation. These results are consistent with the observations that eds5 is an SA-deficient mutant, whereas npr1 is an SA-insensitive mutant.

Figure 4.

Effects of eds5 and npr1 on SA Concentrations in the cpr Mutants.

(A) Free SA in the cpr eds5 double mutants in comparison with that in the cpr mutants.

(B) Free SA in the cpr npr1 double mutants in comparison with that in the cpr mutants.

Leaves from 4-week-old soil-grown plants were collected and analyzed by HPLC for free SA. The values are an average of three replicates ±sd. The cpr1 npr1 double mutant was not tested because of its prohibitively small size. +avr, plants infected with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 3 days before tissue harvest; c1e5, cpr1 eds5; c5e5, cpr5 eds5; c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c6e5, cpr6 eds5; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; FW, fresh weight; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

The difference in SA contents between the cpr eds5 and cpr npr1 mutants may explain the differences in the PR gene expression and pathogen resistance observed in these mutants. To test this hypothesis, we generated cpr nahG double mutants and tested for resistance to P. parasitica Noco2. As was the case for the cpr eds5 mutants, cpr1 nahG, cpr5 nahG, and cpr6 nahG were all susceptible to both P. parasitica Noco2 and P. s. maculicola ES4326 (Table 2). This result, along with the observation that INA treatment can rescue the resistance phenotype in the cpr eds5 double mutants, supports the hypothesis that the susceptibility caused by eds5 on the cpr mutants is a result of their inability to accumulate SA.

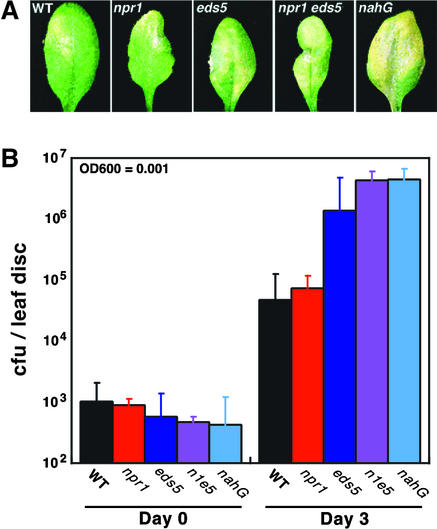

NPR1-Independent, SA-Dependent Signaling in Local Resistance

Because NPR1 is a key component in the SA-mediated SAR signaling pathway, the resistance observed in the cpr npr1 double mutants appears to be mechanistically distinct from SAR. We hypothesized that the resistance response exhibited by the cpr npr1 double mutants might mimic a localized resistance response that can be activated during an avirulent pathogen infection. To test this hypothesis, we infected npr1, eds5, npr1 eds5 (n1e5), and nahG with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 ( ). Because cell death, which is a hallmark of HR, is separable from resistance (Bendahmane et al., 1999; Dinesh-Kumar and Baker, 1999), we detected diminished local resistance by scoring for the appearance of disease symptoms at 3 days after infection. As seen in Figure 5A, wild-type and npr1 plants developed an HR in response to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2, which prevented the pathogen from spreading. In eds5, e5n1, and nahG leaves, the avirulent pathogen was able to cause symptoms that are normally associated with a virulent pathogen, despite the HR-like cell death detected 12 to 24 hr after infection.

). Because cell death, which is a hallmark of HR, is separable from resistance (Bendahmane et al., 1999; Dinesh-Kumar and Baker, 1999), we detected diminished local resistance by scoring for the appearance of disease symptoms at 3 days after infection. As seen in Figure 5A, wild-type and npr1 plants developed an HR in response to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2, which prevented the pathogen from spreading. In eds5, e5n1, and nahG leaves, the avirulent pathogen was able to cause symptoms that are normally associated with a virulent pathogen, despite the HR-like cell death detected 12 to 24 hr after infection.

Figure 5.

Effects of npr1, eds5, and nahG on HR-Mediated Resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2.

(A) Symptoms observed after infection with P. s. maculicola ES4326/ avrRpt2 in wild type, npr1, eds5, npr1 eds5 (n1e5), and nahG.

(B) Quantification of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 growth in wild type, npr1, eds5, n1e5, and nahG. cfu, colony-forming unit; n1e5, npr1 eds5.

Plants were infected with a suspension of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 corresponding to an OD600 of 0.001. Pictures were taken 3 days after infection. Each leaf in (A) is a representative sample from a population of 10 leaves. Leaf discs were collected immediately after infection (day 0) and 3 days later. Four samples from each genotype were collected on day 0; six samples from each genotype were collected on day 3. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits of log-transformed data (Sokal and Rohlf, 1981). The growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 on eds5 plants was similar to that observed by Nawrath and Métraux (1999) but different from that reported by Rogers and Ausubel (1997), who used a less concentrated bacterial inoculum. nahG, transgenic line expressing salicylate hydroxylase; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

To corroborate these visual observations, we assessed the in planta growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 at 3 days after infiltration. As shown in Figure 5B, the wild-type and npr1 plants showed no marked difference in growth of the avirulent pathogen, whereas eds5, n1e5, and nahG had ∼25-fold more pathogen growth, indicating that SA is required for containment of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 during the HR. Therefore, eds5 appears to affect not only SAR but also other defense responses such as HR-mediated resistance.

Generation of the cpr ein2 and cpr jar1 Double Mutants and the cpr npr1 ein2 and cpr npr1 jar1 Triple Mutants

Our previous studies showed that in the c5n1 and c6n1 double mutants, constitutive expression of the antifungal genes PDF1.2 and Thi2.1 was unaffected by the npr1 mutation (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). Because these genes are known to be regulated by JA/ET, we hypothesized that the NPR1-independent resistance observed in the cpr npr1 double mutants may be JA/ET dependent as well as SA dependent. To test this hypothesis, we used an ET-insensitive mutant ein2 (Guzman and Ecker, 1990) and a JA-insensitive mutant jar1 (Staswick et al., 1992) to generate cpr ein2 and cpr jar1 double mutants and cpr npr1 ein2 and cpr npr1 jar1 triple mutants.

Before generating the double and triple mutants, cpr5, cpr6, and npr1 were tested to verify that they did not exhibit phenotypes associated with ET or JA overproduction or insensitivity (see Methods). Using the phenotypes described for the ein2 and jar1 mutants (Guzman and Ecker, 1990; Staswick et al., 1992), we identified the following double and triple mutants: cpr5 ein2 (c5e2), cpr5 jar1 (c5j1), cpr6 ein2 (c6e2), cpr6 jar1 (c6j1), npr1 ein2 (n1e2), npr1 jar1 (n1j2), ein2 jar1 (e2j1), cpr5 npr1 ein2 (c5n1e2), cpr5 npr1 jar1 (c5n1j1), cpr6 npr1 ein2 (c6n1e2), cpr6 npr1 jar1 (c6n1j1), and npr1 ein2 jar1 (n1e2j1) (see Methods).

Initial phenotypic inspection of the double and triple mutants revealed that neither ein2 nor jar1 substantially altered the morphology associated with cpr5, c5n1, cpr6, or c6n1. However, the lesion-forming phenotype in cpr5 and c5n1 was diminished by the ein2 and jar1 mutations. Trypan blue staining revealed that similar to c5e5, both macroscopic and microscopic lesions formed 4 to 7 days later in c5e2 and c5n1e2 than in cpr5 (data not shown).

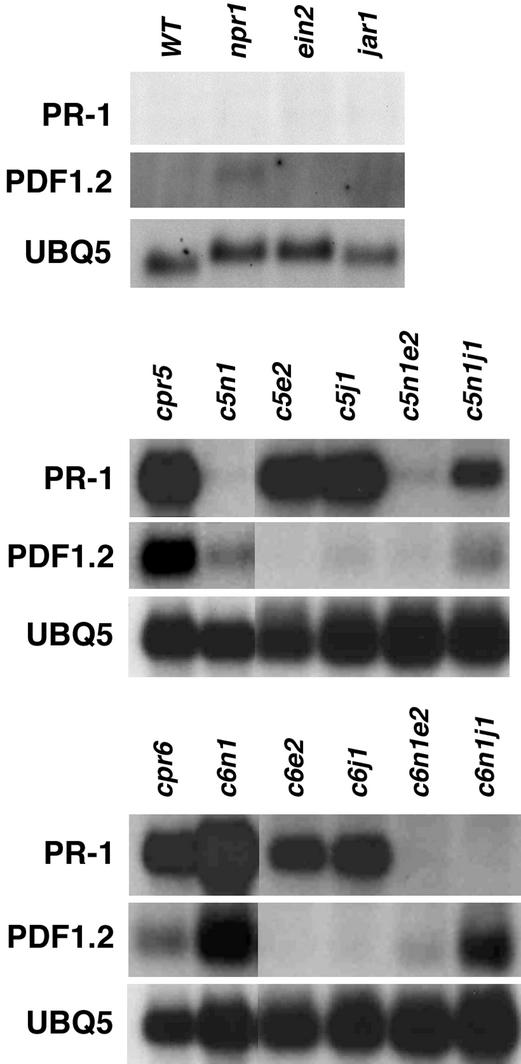

Previous studies have shown that ET insensitivity does not negatively affect the SAR response and may actually potentiate SA-induced PR-1 gene expression (Lawton et al., 1994, 1995), whereas ET insensitivity suppresses the expression of PDF1.2 in response to chemical and biological induction (Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998). We performed RNA gel blot analysis on all the double and triple mutants to determine how JA/ET insensitivity affects PR gene expression in cpr5, c5n1, cpr6, and c6n1. As shown in Figure 6, PR-1 gene expression in the cpr5 mutant was blocked by npr1, which is consistent with our published result (Bowling et al., 1997). Figure 6 shows that PR-1 gene expression in cpr6 was not affected by npr1, which is also consistent with the result reported by Clarke et al. (1998). Interestingly, however, when both npr1 and ein2 were introduced into cpr6, PR-1 gene expression was abolished completely. This suggests that SA-mediated, NPR1-independent expression of the PR-1 gene in cpr6 requires sensitivity to ET. Only when both pathways are blocked is PR-1 expression inhibited. The PDF1.2 gene expression in both cpr5 and cpr6 mutants was suppressed by ein2 (Figure 6). The effect of jar1 on PR gene expression was more variable, which might reflect a leakiness of the mutation or an interaction with the SA signaling pathway.

Figure 6.

Effects of jar1 and ein2 on PR-1 and PDF1.2 Gene Expression in cpr5 and cpr6.

PR-1 and PDF1.2 gene-specific probes were used for RNA gel blot analysis of the indicated genotypes. The UBQ5 transcript was used as a loading standard. RNA was extracted from 4-week-old soil-grown plants. c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c5e2, cpr5 ein2; c5j1, cpr5 jar1; c5n1e2, cpr5 npr1 ein2; c5n1j1, cpr5 npr1 jar1; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; c6e2, cpr6 ein2; c6j1, cpr6 jar1; c6n1e2, cpr6 npr1 ein2; c6n1j1, cpr6 npr1 jar1; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

Effects of JA/ET Insensitivity on the Resistance Induced by cpr5 and cpr6

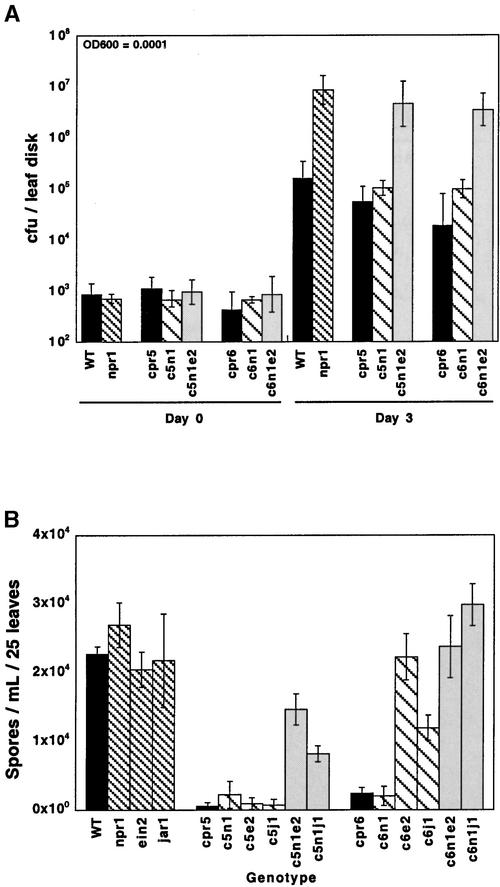

To test the effect of ein2 and jar1 on pathogen resistance, we analyzed the growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326 in all of the double and triple mutants generated with ein2 and jar1. We found that ein2 and jar1 did not alter the resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 conferred by cpr5 or cpr6 (Tables 1 and 2). However, as shown in Figure 7A, the triple mutants c5n1e2 and c6n1e2 were much more susceptible to a low dose of P. s. maculicola ES4326 ( ) than were c5n1 and c6n1. We also tested the double and triple mutants for resistance to P. parasitica Noco2. As shown in Figure 7B, the resistance conferred by the cpr5 mutation was not suppressed unless both the NPR1-mediated and the JA/ET–mediated pathways were blocked (in the c5n1e2 or c5n1j1 triple mutants). The c5n1, c5e2, and c5j1 double mutants were as resistant to P. parasitica Noco2 as was the cpr5 single mutant. In contrast, resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 induced by cpr6 was suppressed by ein2 or jar1 in c6e2, c6j1, c6n1e2, and c6n1j1 (Figure 7B). Treatment with INA restored resistance to the c6e2 and c6j1 double mutants, presumably through inducing NPR1-dependent resistance, which is intact in these mutants (data not shown). Apparently, cpr5 and cpr6 activate different resistance responses to P. parasitica Noco2; one is inhibited only when both NPR1-mediated and ET/JA–mediated resistances are blocked, whereas the other is suppressible by ein2 or jar1 alone. Whether ein2 or jar1 is blocking NPR1-dependent or NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr6 mutant is at this time unclear. The resistance profile of each of the double and triple mutants is summarized in Table 2.

) than were c5n1 and c6n1. We also tested the double and triple mutants for resistance to P. parasitica Noco2. As shown in Figure 7B, the resistance conferred by the cpr5 mutation was not suppressed unless both the NPR1-mediated and the JA/ET–mediated pathways were blocked (in the c5n1e2 or c5n1j1 triple mutants). The c5n1, c5e2, and c5j1 double mutants were as resistant to P. parasitica Noco2 as was the cpr5 single mutant. In contrast, resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 induced by cpr6 was suppressed by ein2 or jar1 in c6e2, c6j1, c6n1e2, and c6n1j1 (Figure 7B). Treatment with INA restored resistance to the c6e2 and c6j1 double mutants, presumably through inducing NPR1-dependent resistance, which is intact in these mutants (data not shown). Apparently, cpr5 and cpr6 activate different resistance responses to P. parasitica Noco2; one is inhibited only when both NPR1-mediated and ET/JA–mediated resistances are blocked, whereas the other is suppressible by ein2 or jar1 alone. Whether ein2 or jar1 is blocking NPR1-dependent or NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr6 mutant is at this time unclear. The resistance profile of each of the double and triple mutants is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Effects of jar1 and ein2 on Resistance in cpr5 and cpr6.

(A) Growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326 on wild type, cpr5, c5n1, c5n1e2, cpr6, c6n1, and c6n1e2. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits of log-transformed data.

(B) Growth of P. parasitica Noco2 on wild type, cpr5, c5n1, c5e2, c5j1, c5n1e2, c5n1j1, cpr6, c6n1, c6e2, c6j1, c6n1e2, and c6n1j1. Error bars indicate se.

Plants were infected and resistance was determined as described in Figures 2 and 3. cfu, colony-forming unit; c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c5e2, cpr5 ein2; c5j1, cpr5 jar1; c5n1e2, cpr5 npr1 ein2; c5n1j1, cpr5 npr1 jar1; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; c6e2, cpr6 ein2; c6j1, cpr6 jar1; c6n1e2, cpr6 npr1 ein2; c6n1j1, cpr6 npr1 jar1; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

SA Accumulation in the cpr ein2 and cpr npr1 ein2 Mutants

To examine the interaction between the SA- and JA/ET–signaling pathways, we measured the endogenous concentrations of SA in c5e2, c5n1e2, c6e2, and c6n1e2. As shown in Figure 8, the blocking of the ET-signaling pathway by ein2 seemed to have opposite effects on SA accumulation in cpr5 and cpr6 mutants. Introducing ein2 into cpr5 increased the amount of endogenous SA by threefold but decreased the amount of SA in cpr6 by half. Interestingly, these phenotypes appeared to be exaggerated in the presence of npr1 in the cpr npr1 ein2 triple mutants (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Effects of ein2 on SA Concentrations in the cpr ein2 and cpr npr1 ein2 Mutants.

Leaves from 4-week-old, soil-grown plants were collected and analyzed by HPLC for free SA. The SA value in c5n1e2 (which is off the scale of the graph) is printed next to the bar to allow a better comparison between samples. The values are an average of two replicates ± range. +avr, plants infected with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 at 3 days before tissue harvest; c5n1, cpr5 npr1; c5e2, cpr5 ein2; c5n1e2, cpr5 npr1 ein2; c6n1, cpr6 npr1; c6e2, cpr6 ein2; c6n1e2, cpr6 npr1 ein2; FW, fresh weight; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

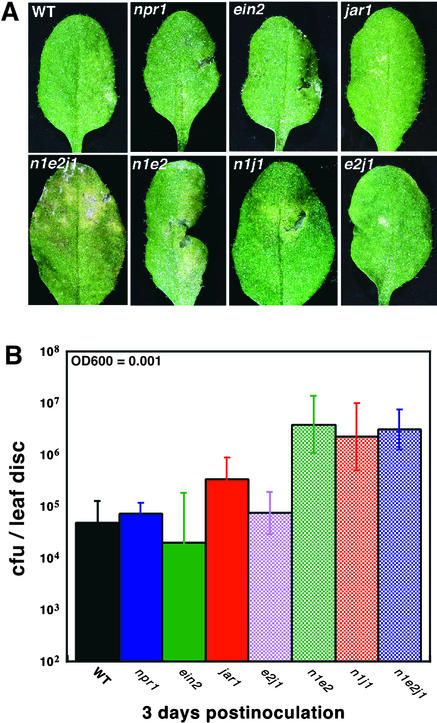

Effects of JA/ET Insensitivity on Local Resistance

The infection experiments presented above showed that blocking JA/ET sensitivity with jar1 and ein2 inhibits NPR1-independent resistance in cpr mutants. If our hypothesis is correct that the NPR1-independent resistance observed in the cpr mutants mimics the local resistance response initiated by HR, we would expect ein2 and jar1 to also affect HR-mediated resistance. Indeed, Figure 9A shows that wild type, npr1, ein2, jar1, and e2j1 responded to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 with a typical HR, which prevented the pathogen from spreading beyond the site of inoculation. In contrast, n1e2, n1j1, and n1e2j1 showed disease symptoms spreading beyond the site of inoculation. The observed symptoms correlated with the growth of bacterial pathogen, as shown in Figure 9B. n1e2, n1j1, and n1e2j1 allowed substantially more growth of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 than did the wild type, npr1, ein2, jar1, or e2j1. These data indicate that EIN2 and JAR1 indeed play roles in establishing local resistance. EIN2/JAR1 and NPR1 may have parallel functions, which may be the reason why susceptibility to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 was observed in n1e2, n1j1, and n1e2j1 but not in npr1, ein2, jar1, or e2j1.

Figure 9.

Effects of jar1, ein2, and npr1 on HR-Mediated Resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2.

(A) Symptoms observed after infection with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 in wild type, npr1, ein2, jar1, e2j1, n1e2, n1j1, and n1e2j1.

(B) Quantification of P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 growth in wild type, npr1, ein2, jar1, e2j1, n1e2, n1j1, and n1e2j1.

Plants were infected and resistance was determined as described in Figure 5. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits of log-transformed data (Sokal and Rohlf, 1981). cfu, colony-forming unit; e2j1, ein2 jar1; n1e2, npr1 ein2; n1j1, npr1 jar1; n1e2j1, npr1 ein2 jar1; WT, wild-type BGL2-GUS transgenic line.

DISCUSSION

This comprehensive epistasis study between the gain-of-resistance cpr mutants and the mutants blocking the SA- and ET/JA–mediated resistance generated a large volume of data. Even though it is unrealistic to interpret all of the data at this time, we have been able to draw the following important conclusions.

cpr Mutants and Pathogen Infection Trigger a Similar Set of Signal Cascades

The cpr mutants used in this analysis all had pleiotropic effects on plant development (Bowling et al., 1994, 1997; Clarke et al., 1998), none of which was suppressed by eds5, ein2, or jar1. The limited molecular information made it difficult to determine whether or not wild-type CPR proteins are normal components of the signaling pathways that regulate resistance. Nevertheless, in this study, the cpr mutants served as useful genetic backgrounds for dissecting the NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance pathways, assessing the loss-of-resistance mutants, and determining the roles of SA, ET, and JA in disease resistance. Through this study, we found that the disease resistance induced by cpr mutants follows biologically relevant signaling pathways. The pattern of PR gene expression in the cpr mutants is similar to that observed in plants induced by P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2. Introduction of eds5 into the cpr mutants inhibits the expression of PR-1 but has little effect on PR-2 or PR-5 (Figure 1). eds5 has been shown to have the same effect on PR gene expression after being induced by the avirulent pathogens P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 and P. s. tomato DC3000/avrRpt2 and by the virulent pathogen P. s. maculicola ES4326 (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999; J.D. Clarke and X. Dong, unpublished results). These results imply that the cpr mutations and bacterial pathogen infection may activate a similar set of resistance responses.

Expression of PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, and PDF1.2 Does Not Correlate with Resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2

Even though we successfully used the PR genes as indicators for active resistance pathways in the cpr mutants, we failed to establish a correlation between expression of PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, and PDF1.2 and resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2. For those mutants in which gene expression is inhibited without affecting resistance (c5n1 for PR-1 in Figures 2, 3, and 6; c5e2 for PDF1.2 in Figures 6 and 7), perhaps a residual amount of gene expression is present that suffices for conferring resistance. However, in those mutants in which PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, and PDF1.2 are unaffected when resistance is blocked (c5e5 mutants in Figures 1 to 3), we conclude that expression of these genes is not sufficient for conferring resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2. This conclusion does not mean that any of these genes individually or in combination do not contribute toward resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2 or to other pathogens that have not been tested. Determining which PR gene combinations are necessary for resistance to a particular pathogen requires comprehensive expression profiling using microarray technology.

Resistance or Susceptibility Often Depends on the Dose of Pathogen Inoculum

In the course of analyzing the responses of the mutants to pathogen infection, we realized that the dose of pathogen applied to the plants is critical for detecting the phenotypes in certain mutants. For example, eds5 was originally reported to affect only resistance to virulent pathogen infection (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997; Volko et al., 1998). However, using different amounts of pathogen inoculum, Nawrath and Métraux (1999) showed that eds5, an SA-deficient mutant, is compromised in HR-mediated local resistance as well as SAR. Similarly, we found that resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 in the cpr npr1 double mutants and the effect of the ET-insensitive ein2 mutation on this resistance were detectable only when a subclinical dose ( ) of the bacterial pathogen was used (Figures 2 and 7A). These data strongly indicate that plant defenses operate in an additive fashion. When exposed to more pathogen inoculum, more defense mechanisms may be required to stop the pathogen growth.

) of the bacterial pathogen was used (Figures 2 and 7A). These data strongly indicate that plant defenses operate in an additive fashion. When exposed to more pathogen inoculum, more defense mechanisms may be required to stop the pathogen growth.

NPR1-Independent Resistance Induced in the cpr Mutants Requires SA- and ET/JA–Mediated Signaling

Epistasis analysis between eds5 and the cpr mutants was designed to determine where eds5 functions in relation to cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6 and by what mechanism cpr5 and cpr6 induce NPR1-independent resistance. Given the loss of resistance to the Pseudomonas and Peronospora pathogens observed in c1e5, c5e5, and c6e5 (Figures 2A and 3A, and Tables 1 and 2), we conclude that eds5 is epistatic to all three cpr mutations. The reduced amounts of SA found in the cpr eds5 double mutants suggest that eds5 suppresses resistance in the cpr mutants by preventing the accumulation of SA (Figure 4A). This conclusion is supported by the loss of resistance observed in the cpr nahG mutant/transgenic (Table 2). Therefore, we believe that the NPR1-independent resistance induced by cpr1, cpr5, and cpr6 is mediated by SA.

In contrast to the cpr eds5 double mutants, the cpr npr1 double mutants have amounts of SA exceeding those found in the cpr parental mutants (Figure 4B). Therefore, wild-type NPR1 may have at least two functions: to transduce the SA signal leading to SAR and to downregulate the amount of SA accumulating in the plant once SAR is established.

The high amount of SA observed in the cpr npr1 double mutants may not be sufficient for conferring the resistance observed in these mutants because resistance cannot be restored in the npr1 mutant by application of large amounts of SA or INA (Cao et al., 1994). To explain how SA-dependent resistance is induced in the SA-insensitive npr1 mutant, we hypothesize that an additional signal, aside from SA, must be required to activate NPR1-independent resistance. This signal or elicitor may be produced as a result of the cpr mutations or derived from the plant or pathogen during the infection process. The existence of such a signal has been proposed (Clarke et al., 1998; Reuber et al., 1998; Rate et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1999) to explain NPR1-independent resistance.

The existence of a second signal is supported by the observation that the ET- and JA-insensitive ein2 and jar1 mutants can also block SA-dependent, NPR1-independent resistance when introduced into cpr npr1 (Figure 7). A possible explanation for this is that EIN2 and JAR1 are involved in transducing this unknown signal. In previous studies, the JA/ET pathway has been shown to be activated by plant cell wall–derived oligogalacturonide or fungus-derived chitosan elicitors (Gundlach et al., 1992). As illustrated in Figure 10A, these results suggest that SA mediates both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr mutants and that NPR1-independent resistance requires sensitivity to JA/ET. However, we were unable to conclude whether the NPR1-dependent pathway is completely nested in the EDS5-mediated pathway, because the eds5 npr1 double mutant is more susceptible to Erysiphe orontii (Reuber et al., 1998) and P. s. maculicola ES4326 (E. Rogers and F.M. Ausubel, unpublished data) than is either mutant alone. Moreover, NPR1 is required for the SA-independent resistance induced by certain root-colonizing bacteria (Pieterse et al., 1998).

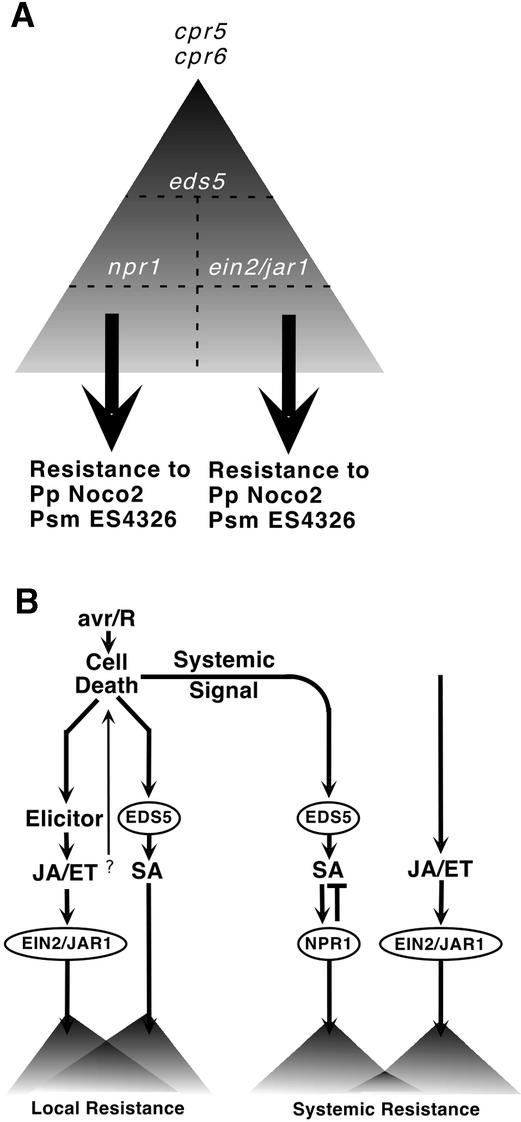

Figure 10.

Model of Interacting Defense Response Pathways.

(A) Model showing the requirements for cpr-mediated resistance. Our data indicate that the cpr mutants activate both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance to P. s. maculicola ES4326 and P. parasitica Noco2. Both pathways are mediated by SA and are blocked by the eds5 mutation. The NPR1-independent pathway also requires sensitivity to JA/ET and is blocked by the jar1 and ein2 mutations. It is not clear at this time whether the resistance to P. parasitica Noco2 in cpr6, which is suppressed by the ein2 and jar1 mutations, is NPR1 dependent or NPR1 independent.

(B) Model overlaying NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance with HR-mediated local and systemic resistance. Our data indicate that NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr mutants resembles the local resistance response triggered during the HR. Avirulent pathogen resistance and NPR1-independent resistance both require SA- and JA/ET–mediated signaling pathways. JA/ET or sensitivity to JA/ET may be required for perception of the signal (elicitor) necessary to bypass the npr1 mutation or for expression of downstream antimicrobial proteins. Therefore, HR-mediated local resistance is shown as a function of overlapping components from both SA- and JA/ET–mediated pathways. Cell death is shown initiating this response, and elements from both the SA and JA/ET pathways are shown to be enhancing the formation of lesions. This feedback loop accounts for SA-dependent lesion mimic mutants as well as the reduction of the lesion-forming phenotype of cpr5 by eds5, ein2, and jar1. NPR1 is shown as being required only for systemic resistance. A second function for NPR1 in feedback regulation of SA accumulation is indicated by a blocked arrow. The cpr mutants are not included in this model because their locations in the signal transduction pathways are not clear. They could function either in the local pathway, inducing NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance simultaneously, or in the systemic pathway, triggering NPR1-independent resistance only when combined with npr1.

NPR1-Independent Resistance Resembles the Local Response Induced during the HR

As has been shown, npr1 blocks PR gene expression and resistance in systemic tissues after induction by a pathogen, indicating that NPR1 is required for establishing resistance in systemic tissues, where SA alone is a sufficient inducer (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995; Glazebrook et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1997; J.D. Clarke and X. Dong, unpublished data). However, in local tissues, resistance to avirulent Pseudomonas pathogens and PR gene expression is not affected substantially by npr1. The NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr mutants may be similar to the local resistance response induced during avirulent pathogen infection. Indeed, the eds5, ein2, and jar1 mutations, which were shown to inhibit NPR1-independent resistance in the cpr mutants, also resulted in a loss in HR-mediated local resistance (Figures 5 and 9). Even though HR-like cell death was detectable in the mutants at 12 to 24 hr after infection, P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 grew and spread like a virulent pathogen.

The mechanism by which eds5, ein2, and jar1 affect the local resistance is unknown. A failure to contain an avirulent pathogen could reflect impairment in turning on HR-mediated resistance or enhanced susceptibility in the host. However, evidence is accumulating that indicates a key role for SA and JA/ET in the HR. The effect of eds5 on HR-mediated resistance is probably the failure to accumulate SA, because removing SA by expressing salicylate hydroxylase in nahG transgenic plants had the same deleterious effect on this response (Figure 5) (Delaney et al., 1994). The role of SA in local resistance has been contemplated biochemically in several publications (Mur et al., 1996; Rao et al., 1997; Shirasu et al., 1997; Thulke and Conrath, 1998). Most revealing is the study by Shirasu et al. (1997), using soybean culture cells, which showed that SA in combination with an avirulent pathogen potentiates a sustained H2O2 burst, activation of cellular-protectant genes, and cell death; all are typical of HR-mediated resistance. The addition of SA alone or in combination with a virulent pathogen does not initiate these responses. Their study supports our hypothesis that NPR1-independent resistance resembles HR-mediated local resistance in showing that SA is an integral part of this local response and that full induction of this response requires an elicitor along with SA.

Researchers have speculated that JA and ET, in addition to SA, play a role in HR-mediated local resistance (Creelman and Mullet, 1997; Johnson and Ecker, 1998; Reymond and Farmer, 1998). For example, genes involved in JA and ET biosynthesis, such as lipoxygenase and ACC synthase, have been shown to be upregulated during an HR (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Slusarenko, 1996). Biosynthesis of JA and ET can also be activated by oligogalacturonide and oligosaccharide elicitors, which can be produced during pathogen infection (Gundlach et al., 1992). Furthermore, ET is produced during race-specific, incompatible interactions in tomato (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996), and methyl jasmonate induces systemic accumulation of H2O2 in tomato and Arabidopsis (Orozco-Cardenas and Ryan, 1999). Genetic evidence for the involvement of ET in the HR comes from the study of ET-insensitive soybean mutants in which the resistance response to some avirulent pathogens is impaired (Hoffman et al., 1999). These data indicate that JA/ET–mediated resistance responds to elicitors and is important for HR-mediated local resistance; further supporting our hypothesis that cpr-induced, NPR1-independent resistance resembles HR-mediated local resistance.

The conditions required for establishing NPR1-independent resistance are depicted in Figure 10B. Given that SA accumulates to greater amounts locally than systemically after infection with an avirulent pathogen and also accumulates to greater amounts locally in response to avirulent pathogens than to virulent ones (reviewed in Sticher et al., 1997), we speculate that a relatively high threshold amount of SA is required to trigger NPR1-independent resistance. This threshold can be achieved in tissues infected with an avirulent pathogen and in cpr npr1 double mutants. In addition to the high concentrations of SA, a second signal or elicitor must also be present to bypass the npr1 mutation and activate the NPR1-independent response. This presumed signal or elicitor may be produced in infected local tissues but not in uninfected systemic tissues. The inhibitory effect of the ein2 and jar1 mutations on the NPR1-independent resistance in cpr npr1 mutants (Figures 7A and 7B) and on HR-mediated resistance (Figures 9A and 9B) suggests that this unidentified signal may be transduced through components of the JA/ET–mediated pathway.

The models in Figures 10A and 10B present only one interpretation of the double and triple mutant study results and assume that the npr1-1, eds5-1, and ein2-1 mutants have null phenotypes. Even though npr1-1, eds5-1, and ein2-1 used in this study are the alleles with the most severe mutant phenotypes (Cao et al., 1994, 1997; Alanso et al., 1999; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999), residual gene activity in these mutants may have affected the results. In light of the requirement for EIN2 and JAR1, we hypothesize that ET and JA are involved in the NPR1-independent resistance. However, it is possible that EIN2 and JAR1 are required for a signaling pathway independent of ET and JA. Finally, there are probably different mechanisms of conferring local resistance; different avirulence signals may trigger different signal pathways. Our study allowed us to speculate only on the pathways activated by the cpr mutations and by P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2. Indeed, in a recent report, McDowell et al. (2000) found that resistance to some avirulent strains of P. parasitica is independent of SA and does not require the function of NPR1 (SA signaling) and COI1 (JA signaling).

In summary, this work greatly extends previous studies describing SA-dependent resistance in npr1 mutants (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998; Reuber et al., 1998; Rate et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1999). The NPR1-dependent pathway, in which SA is a sufficient signal, is used to establish resistance in systemic tissues, whereas the NPR1-independent pathway, which requires both SA and sensitivity to JA and ET, may be involved in conferring HR-mediated local resistance. We anticipate that the diverse array of double and triple mutants constructed for this study (Tables 1 and 2) will be a useful tool for further dissection of disease resistance in plants.

METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown in soil (Metro-Mix 200; Grace-Sierra, Malpitas, CA) or in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 2% sucrose and 0.8% agar under the conditions described in Clarke et al. (1998).

Generation of Double and Triple Mutants

The mutant alleles used throughout this study were cpr1-1 (Bowling et al., 1994), cpr5-1 (Bowling et al., 1997), cpr6-1 (Clarke et al., 1998), npr1-1 (Cao et al., 1994), eds5-1 (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997), ein2-1 (Guzman and Ecker, 1990), and jar1-1 (Staswick et al., 1992).

The Arabidopsis npr1 eds5 double mutant and the transgenic plants (in the Columbia ecotype) expressing the bacterial nahG gene have been described (Reuber et al., 1998). The cpr eds5 double mutants were generated using pollen from the cpr mutants to fertilize the eds5 mutant. Because eds5 was isolated in a fah1-2 mutant background (Glazebrook et al., 1996) and the eds5 locus is ∼10 centimorgans from the fah1-2 locus (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997), eds5 homozygous progeny from each cross were screened in the F2 population for the fah1-2 phenotype. The fah1-2 mutant is deficient in 2-O-sinapoyl-l-malate and can be visualized by the loss of blue-green fluorescence under longwave UV radiation (Chapple et al., 1992). The population enriched for eds5 was then screened for the morphological phenotypes indicative of each cpr mutant (Bowling et al., 1994, 1997; Clarke et al., 1998). Plants that passed both screens were backcrossed to the parental eds5 and cpr to confirm the homozygosity of the loci.

The cpr nahG homozygous lines were generated using pollen from the cpr mutants to fertilize the nahG transgenic plants. The nahG homozygotes were identified as described previously (Bowling et al., 1997). The nahG homozygotes were then transferred to soil, where they were screened for the appropriate cpr morphological phenotypes. The double mutants were further confirmed in the F3 generation.

The cpr1 npr1 double mutant was generated using pollen from the cpr1 plants to fertilize the npr1 plants. The double mutants were identified in the F2 generation by the emergence of a novel phenotype in approximately one-sixteenth of the population. The cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences marker for npr1 (Cao et al., 1997) was used to confirm homozygosity at the npr1 locus, and the presence of the cpr1 morphological phenotype confirmed the homozygosity of cpr1. The generation of the cpr5 npr1 and cpr6 npr1 double mutants has been described previously in Bowling et al. (1997) and Clarke et al. (1998).

The double and triple mutants containing ein2 were generated using pollen from the cpr5, cpr6, npr1, c5n1, and c6n1 genotypes to fertilize ein2. F2 seed was plated on MS plates containing 50 μM 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) and placed in a growth chamber. After 5 days in the dark, the seedlings were scored for the presence or absence of the ethylene (ET)-induced triple response (Guzman and Ecker, 1990). The ein2 mutant, being ET insensitive, does not display the triple response. F2 plants that lacked the triple response were collected and transferred to soil to score for the morphological phenotypes of cpr5 or cpr6. Homozygous npr1 plants were identified using the cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences marker for npr1 (Cao et al., 1997). F3 seed from potential double and triple mutants was collected and rescreened on MS-ACC plates to confirm the presence of the ein2 mutation, on soil to confirm the presence of the cpr mutation, and by polymerase chain reaction to confirm the presence of the npr1 mutation.

The double and triple mutants containing jar1 were generated using pollen from cpr5, cpr6, npr1, c5n1, c6n1, ein2, and n1e2 to fertilize jar1. F2 progeny were grown on MS plates containing 50 μM jasmonic acid (JA) and assayed for the lack of JA-induced responses, which include inhibition of root growth and excessive accumulation of anthocyanin (Staswick et al., 1992). F2 plants that lacked the JA-induced root and anthocyanin phenotypes were transferred to soil and screened for the cpr5 or cpr6 morphological phenotypes. The double and triple mutants were confirmed by repeating the assays stated above in the F3 population.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis

Tissue samples for RNA gel blot analysis were collected from 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on MS plates or on MS plates containing 0.1 mM 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid (INA) or from soil-grown plants at various ages. Samples were prepared and analyzed as described previously in Bowling et al. (1997) and Clarke et al. (1998). Ten micrograms of RNA was separated by electrophoresis through a formaldehyde-agarose gel and transferred to a hybridization membrane (GeneScreen; DuPont–New England Nuclear) as described by Ausubel et al. (1994). 32P-labeled DNA probes for PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, PDF1.2, and UBQ5 were generated using strand-biased polymerase chain reaction as described previously (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 1998).

Pathogen Infections

Infections of plants with Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola ES4326 or Peronospora parasitica Noco2 were performed as described previously (Clarke et al., 1998) with minor modifications. A P. s. maculicola ES4326 inoculum of  is referred to as the clinical dose, whereas that with an OD600 of 0.0001 to 0.0002 is considered the subclinical dose. Infection with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 was done at the clinical dose. Plants used for bacterial infection were grown in soil for 4 weeks and were infected as described previously (Clarke et al., 1998). At 0 and 3 days after inoculation, four to six infected leaves were collected per genotype to measure the growth of the pathogen. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test of the differences between two means of log-transformed data (Sokal and Rohlf, 1981), with the error bars representing 95% confidence limits. Plants infected with P. parasitica Noco2 were grown for 14 days on soil with a 12-hr photoperiod and ∼80% relative humidity and then sprayed with a 10-mL ddH2O suspension of 104 spores mL−1. Seven days after inoculation, the degree of infection was determined by harvesting 25 leaves from approximately five plants in 1 mL of H2O. After vigorous vortex-mixing, two 10-μL aliquots from each sample were examined with a hemacytometer (VWR) to determine the number of spores. Three samples per genotype were assayed to obtain a standard deviation.

is referred to as the clinical dose, whereas that with an OD600 of 0.0001 to 0.0002 is considered the subclinical dose. Infection with P. s. maculicola ES4326/avrRpt2 was done at the clinical dose. Plants used for bacterial infection were grown in soil for 4 weeks and were infected as described previously (Clarke et al., 1998). At 0 and 3 days after inoculation, four to six infected leaves were collected per genotype to measure the growth of the pathogen. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test of the differences between two means of log-transformed data (Sokal and Rohlf, 1981), with the error bars representing 95% confidence limits. Plants infected with P. parasitica Noco2 were grown for 14 days on soil with a 12-hr photoperiod and ∼80% relative humidity and then sprayed with a 10-mL ddH2O suspension of 104 spores mL−1. Seven days after inoculation, the degree of infection was determined by harvesting 25 leaves from approximately five plants in 1 mL of H2O. After vigorous vortex-mixing, two 10-μL aliquots from each sample were examined with a hemacytometer (VWR) to determine the number of spores. Three samples per genotype were assayed to obtain a standard deviation.

Measurement of Salicylic Acid

Four-week-old soil-grown plants were used to measure the concentration of salicylic acid (SA) with a procedure derived from Raskin et al. (1989) and described in Li et al. (1999). This procedure had an ∼25% recovery rate, as determined by extracting known amounts of SA.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Anderson, W. Durrant, W. Fan, M. Kesarwani, and B. Mosher for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (No. 95-37301-1917) and the Monsanto Company awarded to X.D. and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (No. GM48707) awarded to F.M.A.

References

- Alanso, J.M., Hirayama, T., Roman, G., Nourizadeh, S., and Ecker, J.R. (1999). EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 2148–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, F.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K., eds (1994). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. (New York: Greene Publishing Association/Wiley Interscience).

- Baker, B., Zambryski, P., Staskawicz, B., and Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. (1997). Signaling in plant–microbe interactions. Science 276, 726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane, A., Kanyuka, K., and Baulcombe, D.C. (1999). The Rx gene from potato controls separate virus resistance and cell death responses. Plant Cell 11, 781–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent, A.F. (1996). Plant disease resistance genes: Function meets structure. Plant Cell 8, 1757–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker, A.B., Estelle, M.A., Somerville, C., and Kende, H. (1988). Insensitivity to ethylene conferred by a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 241, 1086–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch, J., Verbsky, M.L., Robertson, T.L., Larkin, J.C., and Kunkel, B.N. (1998). Analysis of resistance gene–mediated defense response in Arabidopsis thaliana plants carrying a mutation in CPR5. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, S.A., Guo, A., Cao, H., Gordon, A.S., Klessig, D.F., and Dong, X. (1994). A mutation in Arabidopsis that leads to constitutive expression of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6, 1845–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, S.A., Clarke, J.D., Liu, Y., Klessig, D.F., and Dong, X. (1997). The cpr5 mutant of Arabidopsis expresses both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance. Plant Cell 9, 1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Bowling, S.A., Gordon, A.S., and Dong, X. (1994). Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6, 1583–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Glazebrook, J., Clarke, J.D., Volko, S., and Dong, X. (1997). The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene that controls systemic acquired resistance encodes a novel protein containing ankyrin repeats. Cell 88, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple, C.C.S., Vogt, T., Ellis, B.E., and Sommerville, C. (1992). An Arabidopsis mutant defective in the general phenylpropaniod pathway. Plant Cell 4, 1413–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J.D., Liu, Y., Klessig, D.F., and Dong, X. (1998). Uncoupling PR gene expression from NPR1 and bacterial resistance: Characterization of the dominant Arabidopsis cpr6–1 mutant. Plant Cell 10, 557–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman, R.A., and Mullet, J.E. (1997). Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 48, 355–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L., Dietrich, R.A., and Richberg, M.H. (1996). Death don't have no mercy: Cell death programs in plant–microbe interactions. Plant Cell 8, 1793–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Uknes, S., Vernooij, B., Friedrich, L., Weymann, K., Negrotto, D., Gaffney, T., Gut-Rella, M., Kessmann, H., Ward, E., and Ryals, J. (1994). A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 266, 1247–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Friedrich, L., and Ryals, J.A. (1995). Arabidopsis signal transduction mutant defective in chemically and biologically induced disease resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6602–6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delledonne, M., Xia, Y., Dixon, R.A., and Lamb, C. (1998). Nitric oxide functions as a signal in plant disease resistance. Nature 394, 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh-Kumar, S.P., and Baker, B.J. (1999). Alternatively spliced N resistance gene transcripts: Their possible role in tobacco mosaic virus resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1908–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X. (1998). SA, JA, ethylene, and disease resistance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner, J., Wendehenne, D., and Kelssig, D.F. (1998). Defense gene induction in tobacco by nitric oxide, cyclic GMP and cyclic ADP-ribose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10328–10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi, A.J., Yalpani, N., Silverman, P., and Raskin, I. (1992). Localization, conjugation, and function of salicylic acid in tobacco during the hypersensitive reaction to tobacco mosaic virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 2480–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple, P., Apel, K., and Bohlmann, H. (1995). An Arabidopsis thaliana thionin gene is inducible via a signal transduction pathway different from that for pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Physiol. 109, 813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B.J.F., Benedetti, C.E., Penfold, C.N., and Turner, J.G. (1994). Arabidopsis mutants selected for resistance to the phytotoxin coronatine are male sterile, insensitive to methyl jasmonate, and resistant to a bacterial pathogen. Plant Cell 6, 751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor, H.H. (1947). Host–parasite interactions in flax rust—Its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology 45, 680–685. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, H.H. (1971). Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney, T., Friedrich, L., Vernooij, B., Negrotto, D., Nye, G., Uknes, S., Ward, E., Kessmann, H., and Ryals, J. (1993). Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 261, 754–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J., Rogers, E.E., and Ausubel, F.M. (1996). Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 143, 973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J., Rogers, E.E., and Ausubel, F.M. (1997). Use of Arabidopsis for genetic dissection of plant defense responses. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 547–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlach, J., Volrath, S., Knauf-Beiter, G., Hengy, G., Beckhove, U., Kogel, K.-H., Oostendorp, M., Stauub, T., Ward, E., Kessmann, H., and Ryals, J. (1996). Benzothiadiazole, a novel class of inducers of systemic acquired resistance, activates gene expression and disease resistance in wheat. Plant Cell 8, 629–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach, H., Müller, M.J., Kutchan, T.M., and Zenk, M.H. (1992). Jasmonic acid is a signal transducer in elicitor-induced plant cell cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 2389–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, P., and Ecker, J.R. (1990). Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2, 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Resistance gene–dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 8, 1773–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E., Silverman, P., Raskin, I., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum induce changes in cell morphology and the synthesis of ethylene and salicylic acid in tomato plants carrying the corresponding Cf disease resistance gene. Plant Physiol. 110, 1381–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, T., Schmidt, J.S., Zheng, X., and Bent, A.F. (1999). Isolation of ethylene-insensitive soybean mutants that are altered in pathogen susceptibility and gene-for-gene resistance. Plant Physiol. 119, 935–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.R., and Ecker, J.R. (1998). The ethylene gas signal transduction pathway: A molecular perspective. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32, 227–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen, N.T. (1990). Gene-for-gene complementarity in plant–pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24, 447–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoester, M., Van Loon, L.C., Van Den Heuvel, J., Hennig, J., Bol, J.F., and Linthorst, H.J.M. (1998). Ethylene-insensitive tobacco lacks nonhost resistance against soil-borne fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1933–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C., and Dixon, R.A. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 48, 251–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, K.A., Potter, S.L., Uknes, S., and Ryals, J. (1994). Acquired resistance signal transduction in Arabidopsis is ethylene independent. Plant Cell 6, 581–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, K.A., Weymann, K., Friedrich, L., Vernooij, B., Uknes, S., and Ryals, J. (1995). Systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis requires salicylic acid but not ethylene. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 8, 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Zhang, Y., Clarke, J.D., Li, Y., and Dong, X. (1999). Identification and cloning of a negative regulator of systemic acquired resistance, SNI1, through a screen for suppressors of npr1-1. Cell 98, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low, P.S., and Merida, J.R. (1996). The oxidative burst in plant defense: Function and signal transduction. Physiol. Plant. 96, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Malamy, J., Carr, J.P., Klessig, D.F., and Raskin, I. (1990). Salicylic acid: A likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science 250, 1002–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy, J., Hennig, J., and Klessig, D.F. (1992). Temperature-dependent induction of salicylic acid and its conjugates during the resistance response in tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Cell 4, 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, M.J., Hammond-Kosack, K.E., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Involvement of reactive oxygen species, glutathione metabolism, and lipid peroxidation in the gene-dependent defense response of tomato cotyledons induced by race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Physiol. 110, 1367–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, J.M., Cuzick, A., Can, C., Beynin, J., Dangle, J.L., and Holub, E.B. (2000). Downy mildew (Peronospora parasitica) resistance genes in Arabidopsis vary in functional requirements for NDR1, EDS1, NPR1 and salicylic acid accumulation. Plant J. 22, 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métraux, J.-P., Signer, H., Ryals, J., Ward, E., Wyss-Benz, M., Gaudin, J., Raschdorf, K., Schmid, E., Blum, W., and Inverdi, B. (1990). Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science 250, 1004–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métraux, J.-P., Ahl-Goy, P., Staub, T., Speich, J., Steinemann, A., Ryals, J., and Ward, E. (1991). Induced resistance in cucumber in response to 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid and pathogens. In Advances in Molecular Genetics of Plant–Microbe Interactions, Vol. 1, H. Hennecke and D.P.S. Verma, eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers), pp. 432–439.

- Mur, L.A.J., Naylor, G., Warner, S.A.J., Sugars, J.M., White, R.F., and Draper, J. (1996). Salicylic acid potentiates defense gene expression in tissue exhibiting acquired resistance to pathogen attack. Plant J. 9, 559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath, C., and Métraux, J.P. (1999). Salicylic acid induction–deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 11, 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cardenas, M., and Ryan, C.A. (1999). Hydrogen peroxide is generated systemically in plant leaves by wounding and systemin via the octadecaniod pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6553–6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Eggermont, K., Terras, F.R.G., Thomma, B.P.H.J., De Samblanx, G.W., Buchala, A., Métraux, J.-P., Manners, J.M., and Broekaert, W.F. (1996). Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid–independent pathway. Plant Cell 8, 2309–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Thomma, B.P.H.J., Buchala, A., Métraux, J.P., and Broekaert, W.F. (1998). Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 2103–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J., and van Loon, L.C. (1999). Salicylic acid–independent plant defense pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J., van Wees, S.C.M., Hoffland, E., van Pelt, J.A., and van Loon, L.C. (1996). Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by biocontrol bacteria is independent of salicylic acid accumulation and pathogenesis-related gene expression. Plant Cell 8, 1225–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J., van Wees, S.C.M., van Pelt, J.A., Knoester, M., Laan, R., Gerrits, H., Weisbeek, P.J., and van Loon, L.C. (1998). A novel signaling pathway controlling induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1571–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.V., Paliyath, G., Ormrod, D.P., Murr, D.P., and Watkins, C.B. (1997). Influence of salicylic acid on H2O2 production, oxidative stress, and H2O2-metabolizing enzymes. Plant Physiol. 115, 137–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, I., Turner, I.M., and Melander, W.R. (1989). Regulation of heat production in the inflorescence of an Arum lily by endogenous salicylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 2214–2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J.B., Hammerschmidt, R., and Zook, M.N. (1991). Systemic induction of salicylic acid accumulation in cucumber after inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Plant Physiol. 97, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rate, D.N., Cuence, J.V., Bowman, G.R., Guttman, D.S., and Greenberg, J.T. (1999). The gain-of-function Arabidopsis acd6 mutant reveals novel regulation and function of the salicylic acid signaling pathway in controlling cell death, defense, and cell growth. Plant Cell 11, 1695–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuber, T.L., Plotnikova, J.M., Dewdney, J., Rogers, E.E., Wood, W., and Ausubel, F.M. (1998). Correlation of defense gene induction defects with powdery mildew susceptibility in Arabidopsis enhanced disease susceptibility mutants. Plant J. 16, 473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond, P., and Farmer, E.E. (1998). Jasmonate and salicylate as global signals for defense gene expression. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]