Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of four monthly vitamin D supplementation on the rate of fractures in men and women aged 65 years and over living in the community.

Design

Randomised double blind controlled trial of 100 000 IU oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation or matching placebo every four months over five years.

Setting and participants

2686 people (2037 men and 649 women) aged 65-85 years living in the general community, recruited from the British doctors register and a general practice register in Suffolk.

Main outcome measures

Fracture incidence and total mortality by cause.

Results

After five years 268 men and women had incident fractures, of whom 147 had fractures in common osteoporotic sites (hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae). Relative risks in the vitamin D group compared with the placebo group were 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.99, P=0.04) for any first fracture and 0.67 (0.48 to 0.93, P=0.02) for first hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebral fracture. 471 participants died. The relative risk for total mortality in the vitamin D group compared with the placebo group was 0.88 (0.74 to 1.06, P=0.18). Findings were consistent in men and women and in doctors and the general practice population.

Conclusion

Four monthly supplementation with 100 000 IU oral vitamin D may prevent fractures without adverse effects in men and women living in the general community.

What is already known in this topic

Vitamin D and calcium supplements are effective in preventing fractures in elderly women

Whether isolated vitamin D supplementation prevents fractures is not clear

What this paper adds

Four monthly oral supplementation with 100 000 IU vitamin D reduces fractures in men and women aged over 65 living in the general community

Total fracture incidence was reduced by 22% and fractures in major osteoporotic sites by 33%

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures are projected to increase exponentially worldwide.1 Most fracture prevention trials have focused on clinically defined groups such as people with osteoporosis or previous fractures and have mainly been conducted in women.2–7 Safe, effective, feasible, and cost effective primary prevention measures are needed in older men and women, in whom most osteoporotic fractures occur. We report results from a randomised double blind trial of four monthly supplementation with oral vitamin D3 on fractures and mortality in 2686 men and women aged 65-85 years living in the community.

Methods

Study population

This trial was a pilot to assess the feasibility of a community trial (not subsequently conducted owing to lack of funding) in 20 000 men and women. We recruited men and women aged 65-85 from the British doctors study register at the Clinical Trials Studies Unit, Oxford,8 and the age-sex register of a general practice in Ipswich, Suffolk. Cambridge local ethics committee approved the study.

Recruitment and randomisation

We recruited participants by using a mailed letter and information sheet. We excluded people who were already taking vitamin D supplements and people with conditions that were contraindications to vitamin D supplementation—for example, a history of renal stones, sarcoidosis, or malignancy.

We sent invitations to 11 120 people (9582 from the British doctors study and 1538 from general practice), and 3504 (31.5%) of them (2907 from British doctors study and 597 from general practice) initially agreed to participate. From June 1996 to March 1997 we randomised 2686 (77.5%) people who were eligible and gave informed consent, after stratification by age and sex, to receive either treatment with vitamin D or a placebo. Participants and investigators were blinded to the treatment until the study ended, when Ipswich Pharmacy revealed the coding.

Study design

We conducted the study by post. Participants completed an initial questionnaire. We assessed prevalence of disease with the question “Do you have the following conditions?” followed by a checklist. We used a modified food frequency questionnaire at four years to estimate dietary calcium intake.

Intervention

We sent one capsule containing 100 000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or matching placebo by post every four months for five years (15 doses in total). We asked participants to take the capsule immediately on receipt, complete a form indicating that they had done so, and return the form by Freepost.

The dose had previously been shown to be safe, to raise blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations to physiological levels achievable by lifestyle means, and to have a measurable impact on concentrations of parathyroid hormone over several weeks.9 The expected differences in blood concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone are associated with differences in bone density and fracture risk.10,11

Participants continued any usual drug treatment and any new drugs that were advised during routine care. If they were advised to start vitamin D supplements of more than 200 IU daily they discontinued the trial intervention but continued to be followed for endpoints.

Endpoint ascertainment

On receiving the capsule, participants filled in a checklist of events (fracture or major illness) and returned the form by Freepost. All participants were flagged at the Office for National Statistics for mortality and followed until 31 March 2002. A nosologist blind to the intervention coded death certificates by using ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision). We ascertained incidences of fracture, cardiovascular disease, and cancer by using events identified from questionnaires or death certification by cause.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and heel sonometry

After four years we invited 235 participants from general practice who had taken at least 10 capsules to a clinic for measurement of serum vitamin D and parathyroid hormone concentrations. The visit took place in September and October, about three weeks after a dose. We assessed heel bone sonometry with CUBA equipment (McCue Ultrasonics, Winchester).

Statistical analyses

We included all participants randomised to active vitamin D or placebo in the analyses, according to intention to treat. We compared relative risks for incidence of fracture, mortality by cause, and incidence of cardiovascular disease and cancer for active vitamin D versus placebo by using crude rates and then, after adjustment for age, with the Cox regression method,12 by using SPSS software, version 10.0.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Table 1 shows baseline descriptive data. Mean calcium intake at four years was 742 mg/day and did not differ by treatment allocation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2037 men and 649 women aged 65-85 years at baseline in 1996, according to allocation to treatment with vitamin D or placebo. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Baseline variables

|

All

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D (n=1345)

|

Placebo (n=1341)

|

Vitamin D (n=1019)

|

Placebo (n=1018)

|

Vitamin D (n=326)

|

Placebo (n=323)

|

|||

| Mean (SD) age at randomisation (years) | 74.8 (4.6) | 74.7 (4.6) | 75.2 (4.6) | 75.0 (4.6) | 73.7 (4.5) | 73.6 (4.6) | ||

| Mean (SD) body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.3 (3.4) | 24.4 (3.0) | 24.3 (3.3) | 24.4 (2.7) | 24.4 (3.8) | 24.3 (3.8) | ||

| History of heart disease* | 223 (16.6) | 208 (15.5) | 189 (18.5) | 181 (17.8) | 34 (10.4) | 27 (8.4) | ||

| History of stroke | 51 (3.8) | 57 (4.3) | 42 (4.1) | 48 (4.7) | 9 (2.8) | 9 (2.8) | ||

| History of cardiovascular disease† | 394 (29.3) | 367 (27.4) | 329 (32.3) | 312 (30.6) | 65 (19.9) | 55 (17.0) | ||

| History of cancer‡ | 82 (6.1) | 79 (5.9) | 67 (6.6) | 69 (6.8) | 15 (4.6) | 10 (3.1) | ||

| Current smokers | 59 (4.4) | 53 (4.0) | 39 (3.8) | 29 (2.8) | 20 (6.1) | 24 (7.4) | ||

| Current use of steroids | 60 (4.5) | 70 (5.2) | 42 (4.1) | 53 (5.2) | 18 (5.5) | 17 (5.3) | ||

| Current use of hormone replacement therapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21 (6.4) | 21 (6.5) | ||

| Alcohol intake§: | (n=1295) | (n=1279) | (n=972) | (n=968) | (n=323) | (n=311) | ||

| Never | 132 (10.2) | 115 (9.0) | 77 (7.9) | 64 (6.6) | 55 (17.0) | 51 (16.4) | ||

| Occasional | 197 (15.2) | 205 (16.0) | 102 (10.5) | 115 (11.9) | 95 (29.4) | 90 (28.9) | ||

| Regular | 966 (74.6) | 959 (75.0) | 793 (81.6) | 789 (81.5) | 173 (53.6) | 170 (54.7) | ||

| Physical activity§: | (n=1288) | (n=1276) | (n=969) | (n=963) | (n=319) | (n=313) | ||

| Active or moderately active | 1119 (86.9) | 1133 (88.8) | 840 (86.7) | 852 (88.5) | 279 (87.5) | 281 (89.8) | ||

NA=not applicable.

Self reported angina, myocardial infarction, or ischaemic heart disease.

Ischaemic heart disease, stroke, or other cardiovascular disease.

Includes self reported skin cancers (including melanoma), which comprise about 80% of prevalent cancer; people reporting cancer after randomisation but before taking the first capsule are reported as prevalent cancer.

Excludes missing data.

Incidence of fracture

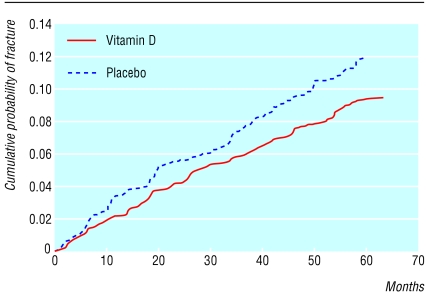

Table 2 shows five year fracture rates. Participants in the vitamin D treatment group had a 22% lower rate for first fracture at any site and a 33% lower rate for a fracture occurring in the hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae. The differences were consistent when stratified by sex or by doctor versus general practice population. We observed differences one year into the study (fig 1).

Table 2.

Incidence of fractures based on self report or mortality certification 1996-2002 and age adjusted relative risks (Cox regression), according to treatment allocation at randomisation (intention to treat) in 2686 men and women aged 65-85 years. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Fractures

|

Vitamin D

|

Placebo

|

Age adjusted relative risk (95% CI)

|

P value*

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | (n=1345) | (n=1341) | ||

| Any site | 119 (8.8) | 149 (11.1) | 0.78 (0.61 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae | 60 (4.5) | 87 (6.5) | 0.67 (0.48 to 0.93) | 0.02 |

| Hip or wrist or forearm | 43 (3.2) | 62 (4.6) | 0.67 (0.46 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Hip | 21 (1.6) | 24 (1.8) | 0.85 (0.47 to 1.53) | 0.59 |

| Vertebrae | 18 (1.3) | 28 (2.1) | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.14) | 0.12 |

| Men | (n=1019) | (n=1018) | ||

| Any site | 77 (7.6) | 91 (8.9) | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.13) | 0.24 |

| Hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae | 36 (3.5) | 50 (4.9) | 0.70 (0.46 to 1.08) | 0.11 |

| Hip or wrist or forearm | 22 (2.2) | 31 (3.0) | 0.70 (0.40 to 1.20) | 0.19 |

| Hip | 11 (1.1) | 14 (1.4) | 0.76 (0.35 to 1.67) | 0.49 |

| Vertebrae | 14 (1.4) | 22 (2.2) | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.22) | 0.17 |

| Women | (n=326) | (n=323) | ||

| Any site | 42 (12.9) | 58 (18.0) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.05 |

| Hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae | 24 (7.4) | 37 (11.5) | 0.61 (0.37 to 1.02) | 0.06 |

| Hip or wrist or forearm | 21 (6.4) | 31 (96) | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.11) | 0.11 |

| Hip | 10 (3.1) | 10 (3.1) | 0.98 (0.41 to 2.36) | 0.97 |

| Vertebrae | 4 (1.2) | 6 (1.9) | 0.65 (0.18 to 2.30) | 0.50 |

P value (two sided) refers to difference between treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of any first fracture according to treatment with vitamin D (n=1345) or placebo (n=1341), based on Cox regression; difference between two groups, P=0.04

Other health events

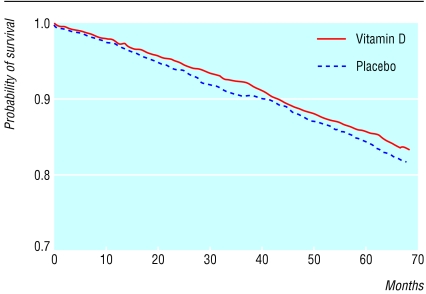

Table 3 shows cumulative mortality to March 2002. The vitamin D group had slightly but not significantly lower mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer than the placebo group. Figure 2 shows the cumulative probability of survival in the vitamin D group compared with the placebo group over five years. Table 4 shows the incidence of major health events. These did not differ significantly between the treatment groups.

Table 3.

Mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer by death certification 1996-2002 and age adjusted relative risks (Cox regression), according to treatment allocation at randomisation (intention to treat) in 2686 men and women aged 65-85 years. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Cause of death*

|

Vitamin D

|

Placebo

|

Age adjusted relative risk (95% CI)

|

P value†

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | (n=1345) | (n=1341) | ||

| All causes | 224 (16.7) | 247 (18.4) | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.06) | 0.18 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 101 (7.5) | 117 (8.7) | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.10) | 0.20 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 42 (3.1) | 49 (3.7) | 0.84 (0.56 to 1.27) | 0.41 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 28 (2.1) | 26 (1.9) | 1.04 (0.61 to 1.77) | 0.89 |

| Cancer | 63 (4.7) | 72 (5.4) | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.20) | 0.37 |

| Colon | 7 (0.5) | 11 (0.8) | 0.62 (0.24 to 1.60) | 0.33 |

| Respiratory | 10 (0.7) | 11 (0.8) | 0.89 (0.38 to 2.09) | 0.78 |

| Men | (n=1019) | (n=1018) | ||

| All causes | 199 (19.5) | 220 (21.2) | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.07) | 0.19 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 90 (8.8) | 106 (10.4) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.10) | 0.19 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 38 (3.7) | 45 (4.4) | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.28) | 0.40 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 24 (2.4) | 25 (2.5) | 0.92 (0.52 to 1.61) | 0.77 |

| Cancer | 56 (5.5) | 59 (5.8) | 0.93 (0.64 to 1.34) | 0.69 |

| Colon | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 0.97 (0.34 to 2.78) | 0.96 |

| Respiratory | 10 (1.0) | 9 (0.9) | 1.08 (0.44 to 2.65) | 0.87 |

| Women | (n=326) | (n=323) | ||

| All causes | 25 (7.7) | 27 (8.4) | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.56) | 0.73 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 11 (3.4) | 11 (3.4) | 0.99 (0.43 to 2.30) | 0.99 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) | 0.99 (0.25 to 3.96) | 0.99 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 3.98 (0.44 to 35.64) | 0.22 |

| Cancer | 7 (2.1) | 13 (4.0) | 0.53 (0.21 to 1.33) | 0.18 |

| Colon | 0 | 4 (1.2) | NA | 0.04 |

| Respiratory | 0 | 2 (0.6) | NA | 0.16 |

| Breast | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

NA=not applicable.

Cardiovascular disease=ICD-9 codes 390.0-459.9; ischaemic heart disease=410.0-414.0; cerebrovascular disease=430.0-438.0; cancer=140.0-239.9; colon cancer=153.0-154.8; respiratory cancer=160.0-165.9; breast cancer=174.0-175.0; each as underlying cause.

P value refers to difference between treatment groups.

Figure 2.

Cumulative survival according to treatment with vitamin D (n=1345) or placebo (n=1341), based on Cox regression; no significant difference between groups

Table 4.

Incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health events 1996-2002 and age adjusted relative risks, according to treatment allocation at randomisation (intention to treat) in 2686 men and women aged 65-85 years. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Health event

|

Vitamin D

|

Placebo

|

Age adjusted relative risk (95% CI)

|

P value*

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | (n=1345) | (n=1341) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease† | 477 (35.5) | 503 (37.5) | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.06) | 0.22 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 224 (16.7) | 233 (17.4) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) | 0.57 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 105 (7.8) | 101 (7.5) | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.36) | 0.87 |

| Cancer† (any) | 188 (14.0) | 173 (12.9) | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.36) | 0.47 |

| Cancer† (excluding skin) | 144 (10.8) | 130 (9.6) | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.42) | 0.43 |

| Colon cancer | 28 (2.1) | 27 (2.0) | 1.02 (0.60 to 1.74) | 0.94 |

| Respiratory cancer | 17 (1.3) | 15 (1.1) | 1.12 (0.56 to 2.25) | 0.75 |

| Self reported falls‡ | (n=1027) | (n=1011) | ||

| 254 (24.7) | 261 (25.8) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) | 0.50 | |

| Self reported health‡: | (n=1017) | (n=1002) | ||

| Excellent or good | 788 (77.5) | 760 (75.8) | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.39) | 0.27 |

| Men | (n=1019) | (n=1018) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease† | 392 (38.5) | 412 (40.5) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) | 0.30 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 191 (18.7) | 193 (19.0) | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.22) | 0.86 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 86 (8.4) | 85 (8.3) | 0.99 (0.72 to 1.36) | 0.96 |

| Cancer† (any) | 163 (16.0) | 147 (14.4) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.42) | 0.39 |

| Cancer† (excluding skin) | 129 (12.7) | 111 (10.9) | 1.17 (0.89 to 1.54) | 0.26 |

| Colon cancer | 25 (2.5) | 21 (2.1) | 1.18 (0.65 to 2.12) | 0.59 |

| Respiratory cancer | 17 (1.7) | 13 (1.3) | 1.29 (0.62 to 2.68) | 0.49 |

| Self reported falls‡ | (n=757) | (n=756) | ||

| 154 (20.3) | 169 (22.4) | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.12) | 0.27 | |

| Self reported health‡: | (n=749) | (n=750) | ||

| Excellent or good | 577 (77.0) | 582 (77.6) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.28) | 0.99 |

| Women | (n=326) | (n=323) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease† | 85 (26.1) | 91 (28.2) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.27) | 0.52 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 33 (10.1) | 40 (12.4) | 0.79 (0.48 to 1.29) | 0.35 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19 (5.8) | 16 (5.0) | 1.19 (0.60 to 2.37) | 0.62 |

| Cancer† (any) | 25 (7.2) | 26 (8.0) | 0.95 (0.54 to 1.68) | 0.85 |

| Cancer† (excluding skin) | 15 (4.6) | 19 (5.9) | 0.77 (0.39 to 1.55) | 0.47 |

| Colon cancer | 3 (0.9) | 6 (1.9) | 0.49 (0.12 to 1.98) | 0.32 |

| Respiratory cancer | 0 | 2 (0.6) | NA | 0.16 |

| Breast cancer | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) | 0.99 (0.25 to 3.99) | 0.99 |

| Self reported falls‡ | (n=270) | (n=255) | ||

| 100 (37.0) | 92 (36.1) | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.48) | 0.86 | |

| Self reported health‡: | (n=268) | (n=252) | ||

| Excellent or good | 211 (78.7) | 178 (70.6) | 1.57 (1.05 to 2.35) | 0.03 |

NA=not applicable.

P value refers to difference between treatment groups.

Self reported incidence or when indicated as cause of death anywhere on death certificate from mortality certification; ICD coding as in table 3.

Data collected at end of trial; excludes missing data. Self reported falls are a positive response to the question, “Have you had any falls in the past 12 months?”

Physiological variables and compliance

Table 5 shows mean serum concentrations of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone and heel bone ultrasound attenuation in the subgroup. Mean vitamin D concentrations were 40% higher in the active treatment group than in the placebo group. Mean parathyroid concentrations were 6% lower, but this difference was not significant. Heel ultrasound measures did not differ by treatment.

Table 5.

Bone heel ultrasound attenuation, velocity of sound, and concentrations of serum vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in subgroup of participants from general practice. Values are means (standard deviations) unless stated otherwise

| Measurement

|

All

|

Men

|

Women

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D (n=124)

|

Placebo (n=114)

|

P value

|

Vitamin D (n=65)

|

Placebo (n=57)

|

P value

|

Vitamin D (n=59)

|

Placebo (n=57)

|

P value

|

|||

| Age (years) | 76.1 (5.1) | 75.4 (4.1) | 0.20 | 75.7 (5.1) | 75.0 (3.6) | 0.37 | 76.6 (5.1) | 75.7 (4.5) | 0.33 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (4.2) | 26.6 (4.2) | 0.15 | 26.9 (4.0) | 26.2 (3.0) | 0.30 | 28.0 (4.5) | 27.1 (5.1) | 0.28 | ||

| Vitamin D (nmol/l) | 74.3 (20.7) | 53.4 (21.1) | <0.001 | 75.6 (19.0) | 61.0 (21.5) | <0.001 | 72.0 (22.5) | 45.37 (17.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Parathyroid hormone (pmol/l) | 5.2 (2.0) | 5.5 (2.4) | 0.25 | 4.8 (2.0) | 5.0 (2.0) | 0.68 | 5.6 (1.9) | 6.13 (2.6) | 0.25 | ||

| Bone heel ultrasound attenuation (dB/MHz) | 74.4 (21.9) | 72.3 (19.7) | 0.45 | 89.1 (15.4) | 83.5 (16.2) | 0.05 | 57.9 (15.4) | 60.95 (16.3) | 0.30 | ||

| Velocity of sound (m/s) | 1618.1 (41.2) | 1613.6 (38.6) | 0.39 | 1641.1 (32.2) | 1629.2 (34.5) | 0.05 | 1592.4 (34.5) | 1597.7 (36.2) | 0.42 | ||

Compliance did not differ between doctors and the general practice population or between the treatment groups; 76% (2050/2686) of participants had at least 80% compliance (12/15 doses). Compliance for the final dose was 66% (1784/2686); excluding participants who had died, we estimated compliance to be 80% (1784/2215). A total of 631 (23.5%) participants, including those who died, did not complete the full five years to March 2002—22.8% (307) in the vitamin D group and 24.2% (324) in the placebo group (P=0.41). No significant difference existed between the two groups in the number known to be alive but who withdrew (that is, discontinued questionnaire follow up) from the study: 5.7% (77) in the placebo group and 6.2% (83) in the active group (P=0.64).

Discussion

Among men and women aged 65-85 living in the general population, those allocated to supplementation with vitamin D had lower rates of fracture at any site or at any major osteoporotic site (hip, wrist or forearm, or vertebrae). We ascertained the incidence of fracture through self report by questionnaire. This may have led to ascertainment errors, but random errors would underestimate associations. In this randomised double blinded design, biased ascertainment between the treatment groups is unlikely. Most of the participants were doctors, which increases the likelihood of accurate ascertainment of events. Fracture rates did not differ significantly between doctors and the general practice population, indicating that people in the general community report fracture accurately, an assumption supported by several studies.13,14

Comparisons with previous studies

Several studies report that daily supplementation with vitamin D and calcium reduces fractures.2,3 Chapuy reported that daily supplementation with vitamin D 800 IU and calcium reduced hip fractures by 30% over three years in 3270 elderly women.2 Whether calcium alone, vitamin D alone, or the combination was responsible for these effects is not clear. In our study the effect size of isolated vitamin D supplementation—about 20% reduction in total fractures and 30% reduction in fractures at major osteoporotic sites—is comparable to that reported by Chapuy for combined daily vitamin D and calcium.2

Previous studies of isolated vitamin D supplementation have been inconclusive.15–17 The lack of significant reduction in fractures in these studies could be explained by a lack of power due to a lower dose of supplement, shorter duration, or lower number of events as well as ineffectiveness of vitamin D. Lips found no protective effect of vitamin D 400 IU daily in 1578 participants.16 This dose may have been too low to achieve a clinical effect. In our study the four monthly 100 000 IU dose averages a daily equivalent similar to the 800 IU vitamin D used in the trials by Chapuy and Dawson Hughes.2,3 Heikinheimo, using annual injections of 150 000-300 000 IU in 899 participants, reported a reduction in fractures of the upper limb but not the lower limb.17 This study was not properly randomised or blinded, and a single annual dose may not provide adequate concentrations in the blood over a whole year.

Vitamin D may protect against fractures through concentrations of parathyroid hormone. Low concentrations of vitamin D are associated with increased concentrations of parathyroid hormone, increased bone resorption, and lower bone mass.9–11 The 40% higher mean concentrations of vitamin D seen in the active treatment group in our trial were still not high in absolute terms. Parathyroid hormone concentrations were only slightly and not significantly lower. This suggests that 100 000 IU vitamin D four monthly may not have lowered parathyroid hormone concentrations adequately, and a more frequent dose might be considered in future trials.

We found no significant effects of vitamin D on total mortality or incidence of cancer or cardiovascular disease, as suggested by observational studies.18,19 However, the fact that the relative risks were in a favourable direction in the active treatment group is reassuring.

Generalisability

To maximise generalisability, this was a pragmatic trial with minimal exclusion criteria. The doctors were similar to the general practice population in terms of compliance, fracture rates, and effects of vitamin D. Blood concentrations of vitamin D in participants taking placebo were comparable to those of population groups of similar ages in northern latitudes in the United States3 and higher than those in older European populations living in northern latitudes.16,20 If vitamin D supplementation is safe and effective for fracture prevention, even in relatively replete healthy participants, it is unlikely to be of lesser benefit in people with lower vitamin D levels.

Public health implications

This trial was a pilot for a larger trial that was not funded and was, consequently, too small for any decisive effect on fractures to be expected. The results, nevertheless, indicate that isolated vitamin D supplementation prevents fractures. This is particularly important for primary prevention. Several interventions—such as bisphosphonates, oestrogen, and calcium and vitamin D—reduce fractures in high risk groups.2–7 Their application to primary prevention is, however, problematic as the balance of risk-benefit and cost-benefit differs in primary and secondary prevention.

The alendronate trial identified 2000 women at high risk of fracture (low bone mineral density and previous fracture).4 The 25% reduction in fractures seen translates to an absolute benefit of 60 women treated for one year to prevent any fracture; the absolute benefit was lower in a later trial on women without a previous fracture.5 Whereas relative reductions in fracture may be generalisable, the absolute benefit differs in groups in which absolute fracture risks are lower. The 22% reduction in fractures in our study translates to approximately 250 people treated for one year to prevent any fracture.

Risk of fracture is related to bone health across the whole population distribution, such that most fractures do not occur in the small numbers of people with severe osteoporosis at very high risk but in the large numbers at moderately increased risk. To have a substantial effect on total fractures in the population, intervention would be needed in large numbers of people; consequently, population-wide preventive interventions have been proposed for all elderly people.21

However, the dilemma for primary prevention is that whereas the population attributable risk is large, the absolute individual risk is still low.22 The risk-benefit balance for community based prevention differs from that for intervention in clinically defined groups. Safety, feasibility, and cost effectiveness are crucial. Side effects are less acceptable in a healthy group in which the risk of fracture is not high. This is a particular issue in men, in whom evidence on effective fracture prevention is lacking. Many interventions effective in high risk groups are not feasible in the general population owing to poor compliance or side effects or are not cost effective.23 In contrast, the cost of four monthly oral 100 000 IU vitamin D is minimal (<£1 annually).

Conclusion

We found a single oral 100 000 IU dose of vitamin D four monthly to be acceptable, safe, and effective in reducing the incidence of fracture in men and women aged over 65 living in the general community.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in the trial from the British doctors study and the general practice in Ipswich. We also thank A J Hicks and colleagues at the Norwich Road Surgery, Ipswich; G Hanson, Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust Pharmacy Manufacturing Department; Richard Dexter, Pelican Computing, for computing support; Rosemary Reader and Sandra Owen for database assistance; and Sir Richard Peto for advice and access to the British doctors. The 100 000 IU vitamin D supplement or placebo used in this trial was specially prepared by the Ipswich Hospital Pharmacy. Ergocalciferol (physiologically the same action as cholecalciferol) 50 000 IU is obtainable from chemists.

Footnotes

Funding: Start up grant from the Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ., 3rd Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992;2:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01623184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1637–1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the fracture intervention trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Mortality in relation to consumption of alcohol: 13 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 1994;309:911–918. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khaw KT, Scragg R, Murphy S. Single dose cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) suppresses the winter increase in parathyroid hormone concentrations in normal older men and women: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1040–1044. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parfitt AM, Gallagher JC, Heaney RP, Johnston CC, Neer R, Whedon GD. Vitamin D and bone health in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:1014–1031. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaw KT, Sneyd MJ, Compston J. Bone density parathyroid hormone and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in middle aged women. BMJ. 1992;305:273–277. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6848.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail AA, O'Neill TW, Cockerill W, Finn JD, Cannata JB, Hoszowski K, et al. Validity of self-report of fractures: results from a prospective study in men and women across Europe. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s001980050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Seeley DG, Cauley JA, Vogt TM, et al. The accuracy of self-report of fractures in elderly women: evidence from a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:490–499. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gillespie WJ, Henry DA, O'Connell DL, Robertson J. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD000227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lips P, Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM. Vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in elderly persons. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:400–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heikinheimo RJ, Inkovaara JA, Harju EJ, Haavisto MV, Kaarela RH, Kataja JM, et al. Annual injection of vitamin D and fractures of aged bones. Calcif Tissue Int. 1992;51:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00298497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scragg R, Jackson R, Holdaway IM, Lim T, Beaglehole R. Myocardial infarction is inversely associated with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels: a community based study. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:559–562. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED. Calcium and vitamin D: their potential roles in colon and breast cancer prevention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;889:107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapuy MC, Preziosi P, Maamer M, Arnaud S, Galan P, Hercberg S, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in an adult normal population. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:439–443. doi: 10.1007/s001980050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett-Connor E, Gore R, Browner WS, Cummings SR. Prevention of osteoporotic hip fracture: global versus high-risk strategies. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:S2–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose G. Strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torgerson D, Donaldson C, Reid D. Using economics to prioritize research: a case study of randomized trials for the prevention of hip fractures due to osteoporosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1:141–146. doi: 10.1177/135581969600100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]