Abstract

Chromosomal instability (CIN), a hallmark of most colon tumors, may promote tumor progression by increasing the rate of genetic aberrations. CIN is thought to arise as a consequence of improper mitosis and spindle checkpoint activity, but its molecular basis remains largely elusive. The majority of colon tumors develop because of mutations in the tumor suppressor APC that lead to Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation and subsequent transcription of target genes, including conductin/AXIN2. Here we demonstrate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling causes CIN via up-regulation of conductin. Human colon tumor samples with CIN show significantly higher expression of conductin than those without. Conductin is up-regulated during mitosis, localizes along the mitotic spindles of colon cancer cells, and binds to polo-like kinase 1. Ectopic expression of conductin or its up-regulation through small interfering RNA-mediated knock-down of APC leads to CIN in chromosomally stable colon cancer cells. High conductin expression compromises the spindle checkpoint, and this requires localized polo-like kinase 1 activity. Knock-down of conductin by small interfering RNA in colon carcinoma cells or gene ablation in mouse embryo fibroblasts enforces the checkpoint.

Keywords: Axin2/conductin, colorectal cancer, Wnt signaling, spindle checkpoint, APC

The Wnt signaling pathway is initiated by binding of Wnt factors to receptors and coreceptors, Frizzled and LRP, respectively, on the cell membrane, which triggers a signaling cascade that leads to the accumulation of β-catenin. In the absence of Wnts, β-catenin is degraded by a multiprotein complex composed of APC, GSK3β, CK1, and the scaffold proteins Axin1 and conductin/Axin2, which induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin and its subsequent proteosomal degradation (1–3). Wnt signals block β-catenin phosphorylation and hence degradation (4). β-Catenin associates with TCF/LEF (T cell factor/lymphocyte enhancer factor) transcription factors to activate target genes that enhance proliferation and cell survival (2, 4, 5). Aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, due to mutations in components of the pathway, is thought to be an initiating event in colorectal carcinogenesis (6–8). Mutations in APC are the earliest and most frequent events in colon tumors, whereas mutations in other components of the pathway, including β-catenin itself, have been reported but are less frequent (4, 7).

CIN is a form of genomic instability that characterizes most cancers, including colon tumors (9). Defined as an increased rate of loss or gain in chromosome numbers and parts, CIN can cause gross changes in gene expression that in turn may promote tumorigenesis (10–13). The causes of CIN are believed to lie in the midst of mitosis, when accurate segregation of chromosomes is established (14). The mitotic spindle checkpoint prevents segregation errors by inhibiting the onset of anaphase until all chromosomes are properly attached to the spindle (15). The effector of the checkpoint is the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome APC/C, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that promotes degradation of mitotic regulators, leading to anaphase initiation (16, 17). APC/C is inhibited by the checkpoint machinery in response to inappropriate microtubule–kinetochore attachments (18). When the checkpoint is satisfied, inhibition of APC/C is relieved and equal segregation of chromatids into daughter cells ensues. A compromised spindle checkpoint allows unequal segregation of genomic material into daughter cells, thus generating CIN (12). Indeed, loss-of-function mutations in spindle checkpoint components have been found in human colon tumors with CIN, albeit in small numbers (14, 19). Thus, although CIN can arise through disregulation of mitosis, its origins in most colon tumors remain unknown. Recently it has been suggested that mutations in APC, in addition to activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, can lead to CIN through a role in microtubule–kinetochore attachments (20–22). It has therefore been proposed that mutations in APC might fulfill both roles for increased proliferation and for CIN, resulting in cell transformation (23).

The scaffold protein of the β-catenin degradation complex, conductin, was shown to be a direct transcriptional target of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and, as a consequence, to be highly up-regulated in the majority of colon tumors (1, 24, 25). Although conductin negatively regulates Wnt signaling by promoting degradation of β-catenin, the high levels of conductin observed in tumors are apparently not sufficient to prevent aberrant signaling. We were therefore interested in whether high conductin expression has any functional relevance in cancer.

In the present study we report that conductin is highly expressed in CIN+ human colon tumors as compared with CIN− tumors and normal mucosa, indicating that the activity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling positively correlates with CIN. We show that aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling leads to CIN in colon cancer cells and that conductin is both necessary and sufficient in this process. We further show that conductin acts on the mitotic spindle checkpoint and binds an important regulator of mitosis, polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). Collectively our results suggest that, in APC-deficient tumors, aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling may lead to chromosomal instability through up-regulation of conductin.

Results

Conductin Is Highly Up-Regulated in CIN Human Colon Tumors.

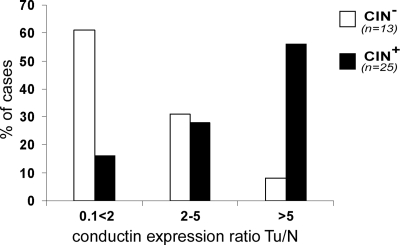

Using FISH analysis on tissue samples we classified tumors into chromosomally stable (CIN−) and instable (CIN+) statuses (see Materials and Methods) and determined expression levels of conductin using real-time RT-PCR (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We observed a significant correlation between high expression of conductin and the CIN+ phenotype (Fig. 1), because ≈60% of CIN+ but only 7% of CIN− tumors showed >5-fold up-regulation of conductin as compared with normal mucosa.

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of conductin is associated with CIN+ but not CIN− colon tumors. Correlation of conductin expression ratios between human colon tumors (Tu) and paired normal mucosa (N) with the CIN status of tumors is shown. Tumor samples were classified as CIN+ and CIN− statuses, and expression ratios for conductin were determined by real-time RT-PCR and adjusted to TXBP151 mRNA levels (see Materials and Methods). Mean expression ratios Tu/N for conductin were 19.5 for CIN+ and 2.2 for CIN− tumors (P < 0.03) (see Table 1).

Overexpression of Conductin Causes CIN.

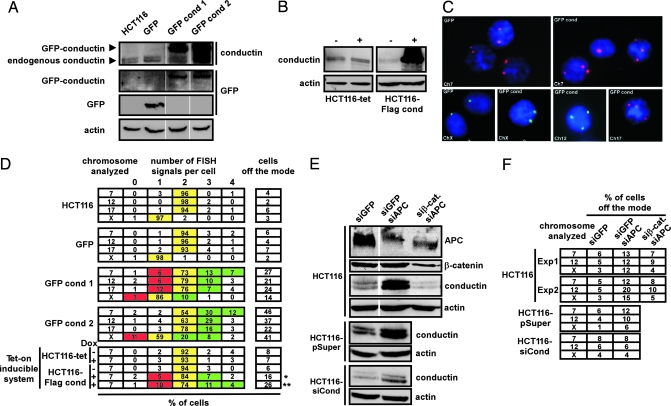

The tumor data prompted us to examine whether excess conductin was sufficient to induce chromosomal instability in HCT116 colon cancer cells, which are chromosomally stable, carry mutated β-catenin but wild-type APC, and express low levels of endogenous conductin as compared with other colon cancer cell lines, by raising conductin expression levels to that of CIN+ cells (13, 14, 26) (see Fig. 5 A and B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We generated GFP- and GFP-conductin-expressing clones from HCT116 cells (Figs. 2A and 5B) and quantified chromosome numbers by FISH of chromosome-specific centromeric enumeration (CEP) probes in interphase nuclei (see Materials and Methods). Nearly all cells in parental HCT116 or GFP-expressing controls showed the regular number of two fluorescent signals for autosomal chromosomes, or one for the X chromosome per nucleus, reflecting the chromosomal stability of these cells (13, 26) (Fig. 2 C and D). Overall, the fraction of cells with signals diverging from the modal value, which is the quantitative index of CIN (13, 14, 26), was within the range of only 2–7%. In contrast, a strikingly high percentage (14–46%) of cells expressing GFP-conductin exhibited gains and losses of chromosomes (Fig. 2 C and D). To analyze the consequence of short-term expression of conductin on CIN, tet-on inducible Flag-conductin-expressing clones (HCT116-Flag cond) were generated (Figs. 2B and 5B). These cells were induced by doxycycline (Dox) for 2 days only, followed by 5 days of further culture, or for a continuous period of 21 days. Both short-term and long-term induction of conductin expression resulted in chromosomal instability, with 16% and 26% of the cells being off the mode, respectively, whereas Dox-treated control cells (HCT116-tet) remained chromosomally stable (Fig. 2D). These findings demonstrate that conductin is sufficient for CIN.

Fig. 2.

Overactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling causes CIN via conductin. (A) Western blotting analysis of lysates from parental HCT116 cells and HCT116 transfectants stably expressing GFP (GFP) or GFP-conductin (GFP cond 1 and GFP cond 2). Blots were probed with antibodies to conductin (C/G7), GFP, and actin (loading control). (B) Western blotting of conductin with C/G7 before (−) and after (+) induction with Dox in clones of HCT116 expressing the tet regulator alone (HCT116-tet) or together with a tet-on inducible vector for Flag-conductin (HCT116-Flag cond). (C) Interphase FISH analysis using chromosome-specific CEP probes for indicated chromosomes in HCT116 cells stably expressing GFP (GFP) or GFP-conductin (GFP cond 1 and GFP cond 2). CEP probes for chromosomes 7 and 17 were labeled with Cy3 (red signals), and CEP probes for chromosomes X and 12 were labeled with Cy2 (green signals). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (D) Quantification of CEP-FISH for indicated chromosomes in parental HCT116 cells, GFP, or GFP cond 1 and GFP cond 2 stable transfectants, and in tet-inducible cells HCT116-tet or HCT-Flag cond cells in the absence (−) or presence (+) of Dox. Numbers in the table show the percentage of cells carrying indicated FISH signals. Yellow indicates the expected signal number per cell for indicated chromosomes (mode), and red and green reflect under- or over-mode positions, respectively. Also shown is the total percentage of cells diverging from the modal position (off-mode) for respective chromosomes. Asterisks indicate short (∗, 2 days) or prolonged (∗∗, 21 days) induction of cells with Dox. (E and F) APC knockdown causes up-regulation of conductin leading to chromosomal instability. (E) Western blotting analysis of lysates from parental HCT116 cells and HCT116 cells stably transfected with a pSUPER plasmid carrying an siRNA sequence targeting conductin expression (HCT116-siCond) or an empty pSUPER plasmid (HCT116-pSuper) after transient transfection with combinations of indicated siRNAs targeting GFP (as a control), APC, and β-catenin. Blots were probed with antibodies to APC, β-catenin, conductin (C/G7), and actin (loading control). (F) Quantification of CEP-FISH for indicated chromosomes in transiently transfected cells as in E after 3 weeks of culture. Numbers reflect the percentage of cells carrying aberrant FISH signals (off the mode).

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Activation Causes CIN via Conductin.

To determine whether activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway would also lead to chromosomal instability through conductin, we down-regulated wild-type APC in HCT116 cells by transfection of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Efficient depletion of APC resulted in a marked increase in conductin levels, as well as an increase in the TOP Flash reporter used to assess β-catenin transcriptional activity (Fig. 2E and data not shown). Up-regulation of conductin as well as high TOP Flash activity were prevented by simultaneous depletion of both APC and β-catenin (Fig. 2E and data not shown). CEP-FISH analysis performed 3 weeks after transfection showed that depletion of APC from HCT116 cells led to CIN, with 12–20% of cells exhibiting aberrant numbers of chromosomes as compared with 3–6% for siRNA against GFP (siGFP) controls (Fig. 2F). CIN was significantly prevented by concurrently depleting β-catenin, with only 4–10% of cells being off the mode, suggesting that CIN occurred as a consequence of aberrant β-catenin activation. Importantly, CIN generated by APC depletion was also prevented in HCT116 cells where conductin was stably knocked down (HCT116-siCond) but not in control cells (HCT116-pSuper) (Fig. 2 E and F). These findings suggest that, in the absence of APC, the resulting aberrant β-catenin signaling leads to CIN through up-regulation of conductin.

Conductin Is Up-Regulated During Mitosis and Binds to PLK1.

We found that expression levels of conductin were higher in mitotic than in nonmitotic SW480 and DLD1 colon cancer cells, as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3A). Conductin levels declined as SW480 cells made an exit from mitosis, paralleling the fall in cyclin B1 levels used for monitoring the timing of mitotic exit (Fig. 3B). When G1/S arrested SW480 cells were released from an aphidicolin block, conductin expression rose as cells progressed into S phase and reached a maximum during mitosis, followed by a fall that coincided with exit from mitosis (Fig. 3C). These data show that expression levels of conductin are regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner, with highest expression during mitosis. We therefore investigated possible interactions between conductin and the known mitotic regulators Mad2, Emi1, cdc27, cyclin B1, Cdc2, and PLK1. As shown in Fig. 3D, endogenous conductin could be coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-PLK1 but not with FLAG-LKB1 used as a control. In lysates from nocodazole-treated SW480 cells, we could coimmunoprecipitate endogenous conductin/PLK1 complexes (Fig. 3E). In addition, GFP-conductin but not GFP could be coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-PLK1 (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The other tested mitotic regulators did not show interaction with conductin in immunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown). PLK1, an important mitotic kinase that regulates diverse mitotic operations, localizes at centrosomes and mitotic spindles (ref. 27; reviewed in ref. 28). In line, we found that conductin localizes at the mitotic spindles as well as at centrosomes during interphase in colon cancer cells (Fig. 5C). In 293T cells, transiently transfected CFP-conductin and Flag-conductin localizes to the mitotic spindle whereas the related protein axin1 (CFP-axin1 or Flag-axin1) does not (Fig. 5D). These data are supportive of a specific role for conductin but not axin1 in mitotic homeostasis.

Fig. 3.

Conductin is regulated during the cell cycle and is found in a complex with PLK1. (A) Western blotting for conductin from mitotic (M) and nonmitotic (NM) SW480 and DLD1 colon cancer cells. Actin blots demonstrate equal loading. (B) Western blotting for conductin and cyclin B1 at indicated time points after release of mitotic SW480 cells from a nocodazole block. (C Left) Western blotting of G1/S synchronized SW480 cells for conductin, cyclin B1, and actin at indicated time points after release from an aphidicolin block. (C Right) FACS profile of propidium iodide-stained cells from the same time course. (D) Immunoprecipitation of Flag-PLK1 or Flag-LKB1 (control) transfected in SW480, followed by Western blotting for endogenous conductin and Flag for both INPUT and immunoprecipitation. (E) Immunoprecipitation from nocodazole-arrested SW480 cells with antibodies against PLK1, conductin, and hemagglutinin (control) followed by Western blotting for endogenous conductin and endogenous PLK1. In D and E, Ig heavy chains are indicated (IgG).

Conductin Compromises the Mitotic Spindle Checkpoint.

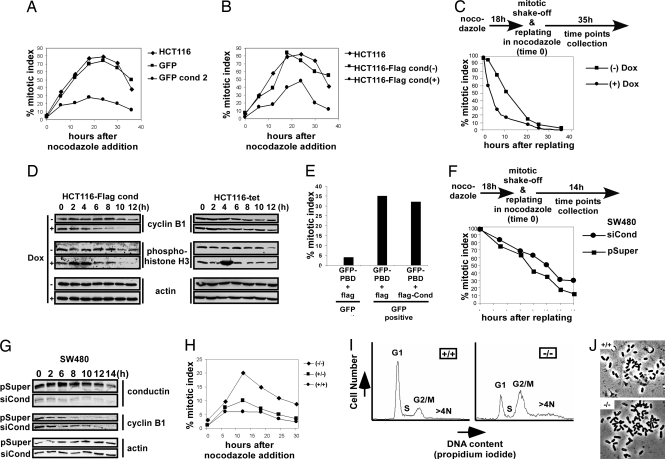

We next analyzed whether conductin might lead to CIN by altering the mitotic spindle checkpoint, using the stable as well as inducible HCT116 clones expressing conductin (see Fig. 2 A and B). Cells were exposed to nocodazole, a microtubule/spindle poison that activates the spindle checkpoint, and at steady intervals the checkpoint activity was determined by measuring the percentage of cells arrested in mitosis (percentage mitotic index). The mitotic index was markedly decreased in cells overexpressing conductin as compared with controls and the parental cells (Fig. 4 A and B). Specifically, after 18 h of nocodazole treatment >80% of parental HCT116 cells were arrested in mitosis, as reported previously, whereas only 20–30% of cells stably expressing GFP-conductin achieved arrest (Fig. 4A) (13, 14). A reduced mitotic arrest was also recorded for HCT116, DLD1, and SW480 cells after tet-on inducible expression of Flag-conductin (Fig. 4B and Fig. 7 A and B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Similarly, in 293T cells transient transfection of Flag-conductin and CFP-conductin also resulted in a low mitotic arrest, whereas CFP-axin1 was less effective (Fig. 7 E and F).

Fig. 4.

Conductin modulates the mitotic spindle checkpoint. (A) Mitotic index time course in parental HCT116 cells and in stable GFP or GFP-conductin transfectants (see Fig. 2A). (B) Mitotic index time course in parental or tet-inducible clones of HCT116 (see Fig. 2B) showing (+) or lacking (−) expression of Flag-conductin after induction with Dox for 24 h. (C) Mitotic index time course of mitotic HCT116-Flag cond cells with (+) or without (−) induction by Dox for 24 h after replating in nocodazole-containing media. (D) Western blotting for cyclin B1, phosphohistone H3, and actin at indicated time points in cells from C. (E) Mitotic indexes of GFP− and GFP+ 293T cells 48 h after cotransfection of GFP-PBD with Flag-conductin or Flag used as a control. (F) Mitotic index time course of SW480 cells stably transfected with a pSUPER plasmid targeting conductin expression (siCond) or an empty pSUPER plasmid (pSuper) after replating in nocodazole-containing media. (G) Western blotting for conductin, cyclin B1, and actin at indicated time points in cells from F. (H) Mitotic index time course of MEFs from wild-type mice (+/+) and from heterozygous (+/−) and homozygous (−/−) conductin knockout mice after addition of nocodazole. (I) FACS analysis of propidium iodide-stained cells of wild-type and conductin knockout MEFs. (J) Metaphase spreads from wild-type and conductin knockout MEFs.

Mitotic HCT116 cells induced to express conductin (+Dox) made a faster exit from mitosis than noninduced cells (−Dox), indicating that conductin overexpression specifically leads to a premature exit from mitosis in the presence of an active spindle checkpoint (Fig. 4C). Mitotic markers cyclin B1 and phosphohistone H3 consistently declined faster in induced cells (Fig. 4D Left). Dox did not alter mitotic exit of HCT116-tet regulator control cells (Fig. 4D Right). In line with a faster exit from mitosis, conductin-expressing cells reattached earlier to the tissue-culture dish than noninduced and control cells (HCT116-tet) and also reached anaphase faster than control cells after removal of nocodazole (Fig. 7 C and D). To analyze whether the observed conductin/PLK1 interaction plays a role in mitotic control, we expressed the polo-binding domain (PBD) of PLK1 (GFP-PBD) alone or together with Flag-conductin in 293T cells and measured the mitotic index. The PBD was shown to arrest cells in mitosis through displacement of endogenous PLK1 from docking proteins and subsequent activation of the spindle checkpoint (29, 30). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the mitotic index within the GFP− (control) cell population was ≈4%. In contrast, 35% of the cells that received GFP-PBD alone were arrested in mitosis. Importantly, coexpression of Flag-conductin could not inhibit this arrest (Fig. 4E). Because conductin can abrogate a nocodazole-induced, but not a PBD-induced, mitotic arrest we conclude that PLK1 localization/activity is required for the function of conductin in mitosis.

To analyze whether reduction of conductin would improve the mitotic spindle checkpoint, we down-regulated conductin by RNA interference in SW480 colon cancer cells, which possess a weak spindle checkpoint, are chromosomally instable, and express high levels of conductin (Fig. 5A) (14). SW480 cells were stably transfected with either the pSUPER-derived RNA interference plasmid targeting conductin (siCond) clones or the empty RNA interference vector pSUPER (pSuper) clones, as a control (Fig. 4G Top). Mitotic cells from these clones were replated in the presence of nocodazole, and the mitotic index and the amounts of cyclin B1 were determined. siCond cells made a significantly slower exit from mitosis than pSuper control cells (Fig. 4F). Specifically, after 14 h 30% of siCond but only 10% of pSuper control cells were still at mitosis. In agreement, cyclin B1 levels declined with slower kinetics in siCond cells than in pSuper control cells (Fig. 4G). We also analyzed the spindle checkpoint in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) from wild-type (+/+) mice as well as from heterozygous (+/−) and homozygous (−/−) conductin knockout mice (Fig. 4H and Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) (B.J. and W.B., unpublished observations). Conductin knockout MEFs achieved 2- to 3-fold higher mitotic indexes than heterozygous and wild-type MEFs, implying that the absence of conductin allows overactivation of the spindle checkpoint in response to spindle stress (Fig. 4H). FACS analysis revealed that, in contrast to wild-type MEFs, a higher fraction of conductin knockout MEFs were found at the G2/M stage of the cell cycle. In addition, a significantly higher fraction of cells with >4 N DNA content was apparent in knockout but not wild-type MEFs, indicating polyploidy in the latter (Fig. 4I). Metaphase spreads frequently showed an abnormal number of chromosomes in conductin knockout MEFs but not in wild-type cells (Fig. 4J). Together these results suggest an innate role of conductin in mitosis.

Discussion

CIN in Colon Cancer.

The molecular basis for CIN is largely unknown, with only a subset of colorectal tumors exhibiting mutations in genes involved in mitotic spindle checkpoint control as well as in cell-cycle regulation (14, 19, 31). Mutations in the APC tumor suppressor, which lead to deregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, have been described as the earliest detectable genetic changes in the majority of colon tumors (6, 7). Our data suggest a mechanism as to how the deregulated Wnt/β-catenin pathway could generate chromosomal instability. In our model, mutations in APC lead to aberrant Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional activity and subsequent up-regulation of conductin, which negatively regulates the mitotic spindle checkpoint, allowing spindle stress to result in an increased rate of chromosomal instability. In support of our model, we found conductin to be highly up-regulated in colon tumors with CIN as compared to tumors without CIN and normal mucosae. Interestingly, conductin was recently shown to be silenced in microsatellite instable colon tumors, which represent a subset of colon tumors characteristically devoid of CIN (32). In addition, inactivation of APC presents a source of spindle stress: it was shown that APC is required for microtubule outgrowth as well as for the association of spindle microtubules with the kinetochores of chromosomes (22, 33), and loss of APC causes chromosomal instability in embryonic stem cells (20, 21). Thus, mutations in APC could act as a dual attack on genomic integrity by coupling spindle damage to a conductin-induced compromise of the mitotic spindle checkpoint. In addition to its already established functions, the Wnt pathway may define the course of genomic instability a cancer assumes and its clinical outcome.

Molecular Mechanism.

What is the molecular mechanism by which conductin regulates the mitotic spindle checkpoint? We noted that conductin overexpression did not affect the integrity of spindle microtubules and did not cause any obvious defects in spindle orientation, as assessed by α-tubulin staining. This finding indicates that conductin may regulate the mitotic spindle checkpoint through signaling, rather than mechanical interference at the mitotic spindle apparatus. Among several candidate mitotic regulators analyzed, we found PLK1 to interact with conductin in immunoprecipitation experiments. PLK1 is a serine/threonine kinase important in numerous processes during mitosis, and its role in the regulation of the spindle checkpoint is well established, suggesting that conductin could act via PLK1 (27, 28, 34–36). The multiple defects that arise from depletion of PLK1 function, e.g., through siRNA mediated knock-down, precludes straightforward testing of this possibility (37, 38). Instead, we specifically perturbed spindle checkpoint activation by expressing the PBD of PLK1, which interferes with localized PLK1 activity (29, 30). Conductin could not abrogate spindle activation in response to PBD expression. This finding suggests that conductin requires localized PLK1 activity for spindle checkpoint suppression. Considering that the two proteins are found in a complex collectively the data indicate that conductin could act upstream of PLK1. It is of interest that several other Wnt pathway components such as APC, GSK3β, and β-catenin have been found associated with the spindle apparatus (22, 39, 40). It remains to be determined whether these factors assemble at the spindle as a complex similar to the β-catenin destruction complex or act independent of each other.

Growth-Promoting Pathways and Mitotic Control.

Another question arising from this study concerns the role of growth pathways in the regulation of mitotic events. It is well established that the Wnt pathway promotes the G1/S transition of the cell cycle by transcriptional activation of regulators such as cyclin D1 and c-myc (4). In this sense it acts similar to other growth-promoting pathways, during the early stages of the cell cycle. We propose that Wnt signaling also controls late events of the cell cycle by modulating mitosis. The up-regulation of conductin could modify the mitotic spindle checkpoint such as to allow appropriate execution of mitosis under growth-promoting conditions. One can speculate that high checkpoint activity in the absence of growth stimulation prevents premature mitosis even in the event of mistakes, e.g., mutations in mitotic regulators. The requirement for a second key to the lock, the Wnt signaling, might serve as a safety mechanism to ensure appropriate checkpoint activity in the absence of the “just right” growth signal. We can speculate that other growth-promoting pathways have evolved similar mechanisms to regulate mitotic progression, which could lead to CIN in case of aberrant activation (41).

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfections.

HCT116, SW480, and DLD1 colon cancer cells and 293T human embryonic kidney cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C/10% CO2. MEFs were isolated from embryos at embryonic day 14.5 as described in ref. 42. For the generation of cell lines stably expressing GFP-conductin, HCT116 cells were transfected with a pEGFP expression vector (CLONTECH) in which the mouse conductin cDNA was cloned C-terminal of the GFP tag (GFP-conductin), together with the pSV2neo plasmid carrying the neomycin resistance gene. Clones were selected in media supplemented with 800 μg/ml G418. Inducible HCT116 and SW480 cell lines expressing Flag-conductin under the control of the tet repressor were generated by transfection with the tet-transactivator plasmid pWHE146 (43), which also carries a neomycin resistance cassette, followed by selection in media supplemented with 500 μg/ml G418. Subsequently, the expression vector pTRE2 (CLONTECH) containing Flag-conductin under the control of a tet-responsive promoter and carrying a hygromycin resistance cassette was transfected, followed by selection in culture media supplemented with 500 μg/ml G418 and 200 μg/ml hygromycin B. For transient transfections in 293T cells, the PBD of PLK1 (amino acids 306–603) as well as CFP-conductin and CFP-axin were used (29, 44). For stable siRNA expression, SW480 and HCT116 cells were transfected with the mammalian expression vector pSUPER (45) carrying a 19-nucleotide sequence (gagatggcatcaagaagca) of human conductin. For transient transfection of synthetic oligo siRNAs, sequences targeting human APC (aagacguugcgagaaguugga), human β-catenin (aaacugcuaaaugacgaggac), and GFP (aagcuaccuguuccauggcca) were used. Plasmid and siRNA transfections were performed with ESCORT V (Sigma) and TransIT-TKO (Mirus), respectively.

CEP-FISH.

CEP-FISH (26) probes conjugated to Cy2 or Cy3 and specific for chromosomes 7 and 12 (Cy3) and chromosomes X and 17 (Cy2) were purchased from Qbiogene and used according to the manufacturer's protocols. Fluorescence signals of between 600 and 1,000 nuclei were counted.

Western Blotting and Coimmunoprecipitation.

Preparation of cell lysates, Western blotting, and coimmunoprecipitations was carried out as described (25). PLK1 immunoprecipitation was performed according to ref. 46. Antibodies against conductin (C/G7) (25), cyclin B1 (Upstate Biotechnology), phosphohistone H3 (Upstate Biotechnology), APC (Ab2) (Oncogene), PLK1 (Zymed Laboratories), and β-actin (Sigma) were used. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Dianova.

Mitotic Index.

To determine mitotic indexes, cells were seeded into six-well plates, and 24 h later nocodazole (0.2 μg/ml) (Sigma) was added. Mitotic cells were isolated by shake-off, and adherent cells were harvested by trypsinization. The mitotic and nonmitotic cells were pooled, washed with PBS, and smeared on glass slides. Cells were briefly dried, and anti-phosphohistone H3 immunofluorescence staining was performed. For mitotic exit assays, nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells were reseeded in the presence of nocodazole in six-well plates.

Cell Synchronization and Flow Cytometry (FACS).

For mitotic synchronization, nocodazole-arrested cells were reseeded in normal media after washing. Synchronization at G1/S was performed with aphidicolin (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. For FACS analysis, trypsinized cells were fixed in ethanol, rehydrated in PBS, and treated with 40 μg/ml propidium iodide and 10 μg/ml RNase for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Cytogenetics.

MEFs seeded for 24 h were treated with vinblastin (80 ng/ml) for 1 h to arrest cells in metaphase. Cells were trypsinized and incubated in 75 mM KCl for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then fixed in three changes of methanol/acetic acid (3:1), and the fixed cell pellets were spread on slides and allowed to air dry for at least 2 days at room temperature before examination.

Tumor Tissue Sample Analysis.

Frozen colorectal cancer and paired normal mucosa samples (from patients who underwent colon resection for colorectal adenocarcinoma at the University of Regensburg) were obtained after approval by the Institutional Review Board. For CIN assessment, touch preparations were performed from frozen tumor samples according to ref. 47. Samples were fixed in Carnoy solution (75% methanol/25% acetic acid) for 20 min, air-dried, and hybridized with CEP-FISH probes according to the UroVysion pretreatment and hybridization protocol (Vysis). After DAPI counterstaining, fluorescence signals were counted by using an Aristoplan fluorescence microscope (Leica). Tumors showing centromere mean values >2.2 or <1.8 (CEP7 and CEP17) and >2.4 and <1.6 (CEP3) were considered as CIN+. Negative controls (normal colonic mucosa) showed mean centromer values of 2.0 ± 0.05 (CEP7 and CEP17) and 2.0 ± 0.11 (CEP3). Mean values were derived from at least 100 counted tumor cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Truss for help with designing siRNAs, E. Gebhart and M. Kirsch for help with CEP-FISH, C. Berens (University Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany) for providing plasmids, E. A. Nigg and H. H. Silljie (Max Planck Institute, Munich) for reagents and helpful discussions, M. Reichel for providing Tet-inducible SW480 and DLD1 clones, and A. Döbler for secretarial work. This work was supported by a grant from Sonderforschungsbereich 473 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to J.B.).

Abbreviations

- CIN

chromosomal instability

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- MEF

mouse embryo fibroblast

- PLK1

polo-like kinase 1

- CEP

centromeric enumeration

- PBD

polo-binding domain

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Behrens J., Jerchow B. A., Wurtele M., Grimm J., Asbrand C., Wirtz R., Kuhl M., Wedlich D., Birchmeier W. Science. 1998;280:596–599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidensticker M. J., Behrens J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1495:168–182. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda S., Kishida S., Yamamoto H., Murai H., Koyama S., Kikuchi A. EMBO J. 1998;17:1371–1384. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lustig B., Behrens J. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2003;129:199–221. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrens J., von Kries J. P., Kuhl M., Bruhn L., Wedlich D., Grosschedl R., Birchmeier W. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morin P. J., Sparks A. B., Korinek V., Barker N., Clevers H., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell S. M., Zilz N., Beazer-Barclay Y., Bryan T. M., Hamilton S. R., Thibodeau S. N., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. Nature. 1992;359:235–237. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Wetering M., Sancho E., Verweij C., de Lau W., Oving I., Hurlstone A., van der Horn K., Batlle E., Coudreuse D., Haramis A. P., et al. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jallepalli P. V., Lengauer C. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2001;1:109–117. doi: 10.1038/35101065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowak M. A., Komarova N. L., Sengupta A., Jallepalli P. V., Shih Ie M., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16226–16231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202617399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajagopalan H., Nowak M. A., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kops G. J., Weaver B. A., Cleveland D. W. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. Nature. 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cahill D. P., Lengauer C., Yu J., Riggins G. J., Willson J. K., Markowitz S. D., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. Nature. 1998;392:300–303. doi: 10.1038/32688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicklas R. B. Science. 1997;275:632–637. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen-Fix O., Peters J. M., Kirschner M. W., Koshland D. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3081–3093. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang G., Yu H., Kirschner M. W. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B. 1999;354:1583–1590. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang G., Yu H., Kirschner M. W. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1871–1883. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai Y., Shiratori Y., Kato N., Inoue T., Omata M. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1999;90:837–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan K. B., Burds A. A., Swedlow J. R., Bekir S. S., Sorger P. K., Nathke I. S. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:429–432. doi: 10.1038/35070123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fodde R., Kuipers J., Rosenberg C., Smits R., Kielman M., Gaspar C., van Es J. H., Breukel C., Wiegant J., Giles R. H., Clevers H. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:433–438. doi: 10.1038/35070129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green R. A., Kaplan K. B. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fodde R., Smits R., Clevers H. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mai M., Qian C., Yokomizo A., Smith D. I., Liu W. Genomics. 1999;55:341–344. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lustig B., Jerchow B., Sachs M., Weiler S., Pietsch T., Karsten U., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Schlag P. M., Birchmeier W., Behrens J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:1184–1193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jallepalli P. V., Waizenegger I. C., Bunz F., Langer S., Speicher M. R., Peters J. M., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. Cell. 2001;105:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golsteyn R. M., Mundt K. E., Fry A. M., Nigg E. A. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:1617–1628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barr F. A., Sillje H. H., Nigg E. A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang Y. J., Lin C. Y., Ma S., Erikson R. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1984–1989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042689299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanisch A., Wehner A., Nigg E. A., Sillje H. H. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:448–459. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopalan H., Jallepalli P. V., Rago C., Velculescu V. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. Nature. 2004;428:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koinuma K., Yamashita Y., Liu W., Hatanaka H., Kurashina K., Wada T., Takada S., Kaneda R., Choi Y. L., Fujiwara S. I., et al. Oncogene. 2005;25:139–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zumbrunn J., Kinoshita K., Hyman A. A., Nathke I. S. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahonen L. J., Kallio M. J., Daum J. R., Bolton M., Manke I. A., Yaffe M. B., Stukenberg P. T., Gorbsky G. J. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1078–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Weerdt B. C., van Vugt M. A., Lindon C., Kauw J. J., Rozendaal M. J., Klompmaker R., Wolthuis R. M., Medema R. H. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:2031–2044. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.2031-2044.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumara I., Gimenez-Abian J. F., Gerlich D., Hirota T., Kraft C., de la Torre C., Ellenberg J., Peters J. M. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1712–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X., Erikson R. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5789–5794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031523100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan Y., Zheng S., Xu Z. F., Ding J. Y. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4596–4599. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i29.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakefield J. G., Stephens D. J., Tavare J. M. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:637–646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan D. D., Meigs T. E., Kelly P., Casey P. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10829–10832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernando E., Nahle Z., Juan G., Diaz-Rodriguez E., Alaminos M., Hemann M., Michel L., Mittal V., Gerald W., Benezra R., et al. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hogan B., Beddington R., Costantini F., Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1994. pp. 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knott A., Garke K., Urlinger S., Guthmann J., Muller Y., Thellmann M., Hillen W. Biotechniques. 2002;32:796, 798, 800. doi: 10.2144/02324st06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieghoff E., Behrens J., Mayr B. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1453–1463. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brummelkamp T. R., Bernards R., Agami R. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Litvak V., Argov R., Dahan N., Ramachandran S., Amarilio R., Shainskaya A., Lev S. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kovach J. S., McGovern R. M., Cassady J. D., Swanson S. K., Wold L. E., Vogelstein B., Sommer S. S. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1004–1009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.14.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.