Abstract

Healthier lifestyles and better medical care are contributing to greater life expectancy in U.S. males. Couple this with the great emphasis our society places on youth, and it is not surprising that older men want to look, feel, and act younger. Androgen replacement may have a role in this setting, but it is not clear exactly what symptoms signal a problem or warrant therapy. A valid and reproducible index that sufficiently defines the problems experienced by androgen-deficient men will go a long way toward helping both researchers and clinicians better understand and manage these men.

Key words: Androgen deficiency, Symptom index, Quality of life

Hormone replacement in postmenopausal women has been commonplace for decades, but hormone replacement in aging men has only recently gained interest in the urologic community. Urologists are familiar with giving exogenous androgen to truly hypogonadal men, in the form of parenteral—and more recently transdermal—preparations, but the use of testosterone to treat decreasing serum levels in older men is a relatively new concept. Terms such as andropause and ADAM (androgen deficiency in aging males) have been introduced, but little is known as to whether this is a true syndrome or simply a function of the normal physiologic aging process. Testosterone levels clearly decline with age,1 but whether this is associated with an identifiable symptom complex is less certain.

The symptoms associated with menopause in females result from a rapid decline in hormones. The more gradual decline in androgen levels in older males may result in perceptible symptoms in some but not in others. It would be highly useful to have a clinimetrically and psychometrically valid2 and reproducible instrument to evaluate men with androgen deficiency. This would both aid research in evaluating new therapies and be useful to clinicians who treat these men.

The goals of any metric in clinical medicine are precision and accuracy. Tools used for measurement must be reliable and valid, allowing comparison among subjects in both clinical and research settings. The methodologic framework exists to develop these kinds of instruments, and it can be applied to men with androgen deficiency, just as it has been applied to many other urologic conditions, such as lower urinary tract symptoms,3 erectile dysfunction,4 interstitial cystitis,5 and chronic prostatitis.6

Developing a New Instrument

Step 1: Searching the Literature

The first step in instrument development is to perform a search of the available literature. Two publications surfaced in this search. The first of these was by Morley and associates,7 who described the study of 316 Canadian physicians, aged 40–62 years. Bioavailable testosterone (BT) was measured in all men, and a set of 10 questions (Table 1) was developed in an attempt to correlate symptoms with BT levels. When administered twice (2–4 weeks apart) to 10 men, this ADAM questionnaire was determined to have a coefficient of variation of 11.5%; and of 21 men in the study treated with testosterone replacement, 18 showed improvement in responses to the questionnaire. This instrument is a good beginning, but response frames are dichotomous (yes or no), which is limits its specificity. Visual analog scales or Likert scales offer greater opportunity to numerically quantify responses.

Table 1.

Questions Used as Part of the Saint Louis University ADAM Questionnaire

|

A positive questionnaire result is defined as a “yes” answer to questions 1 or 7 or any three other questions. ADAM, androgen deficiency in aging males. Table reprinted with permission from Morley et al.7

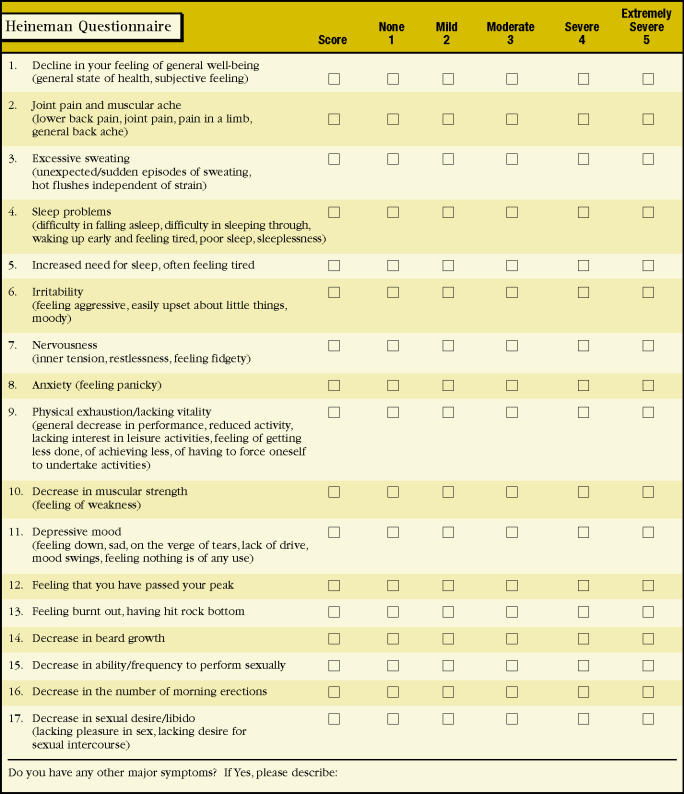

Another instrument was developed in Germany by Heinemann and colleagues and linguistically and culturally adapted for an English version.8 It consists of 17 items, ranging from the general (feeling of well being) to the specific (decrease in beard growth) (Figure 1). Factor analyses were used in the development of the original German version to establish a raw scale and identify its dimensions. A “representative population” of 992 German men was used for the validation study. Further details on the psychometric properties of this instrument are not available in English. This instrument is an improvement over Morley’s ADAM questionnaire, in that these authors developed items in multiple dimensions, recognizing the importance of separate potential domains of androgen deficiency—namely sexual, somatic, and psychological. A comprehensive battery that includes these constructs is the ideal; however, lengthy questionnaires are limited in their usefulness. Study subjects, in general, have a short span of attention. Both study subjects and researchers benefit from parsimonious instruments.

Figure 1.

Aging Male Symptom Rating. Reprinted with permission from Heineman et al.8

Step 2: Item Development

Proper questionnaire design involves determining what experts as well as patients believe is important about the illness experience and whether candidate items mean the same thing to everyone. Focus groups can be helpful in this circumstance. Table 2 lists the most common symptoms associated with androgen deficiency. Based on input from focus groups and a panel of experts, items can be generated from these domains and framed to provide as much information as possible. Responses are measured on an ordinal (Likert) scale. If multiple items in this potential set of questions seem to be measuring the same concept, it is said to be internally consistent. This is measured statistically as Cronbach’s α.9 A good index has a relatively high value of Cronbach’s α, indicating that all the items are indeed measuring the same concept.

Table 2.

Symptoms Associated with Androgen Deficiency

|

Step 3: Validation

A valid index is one that measures what it intends to measure. Content, or “face” validity, is achieved when the questionnaire covers the range of symptoms both patients and clinicians believe to adequately describe the condition (in this case, androgen deficiency). Accomplishing this will be a challenging task. Construct validity may be less of a challenge, because in the case of androgen deficiency there is a time-honored and tested clinical parameter, namely serum testosterone. During the validation study of any new index, serum testosterone sampling will be required. Although no test can perfectly distinguish between diseased and non-diseased states, discriminant validity is important if this proposed instrument is to be used to distinguish between normal and abnormal men with respect to their androgen status. Therefore, a “control” population of men, with normal testosterone levels, will be required in the validation study.

In the initial development phase, purposefully redundant questions are generally proposed, to determine which are most internally consistent and thus perform best. Those that correlate best with some measure of overall concern among the study subjects are the best candidates for the proposed index. In other words, the greater the extent to which an individual symptom is correlated with a specific question that asks subjects about how bothersome that symptom is, the more it appears to matter to him and the greater weight it should be given. The key premise is that the symptoms that are the most important to measure are those that matter most to the patient.

Quality of Life Instruments

Most symptom indexes for medical conditions, including the two presented here (Table 1, Figure 1) focus largely on the illness experience itself rather than what impact it may have on patients’ functional status. Quality of life instruments can fill this gap. They can be disease-specific, with questions that explore how the condition of concern impacts an individual’s mental or general health, as does the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index.10 Alternatively, they can be generic, containing questions designed to be answered by any patient with any type of condition, focusing on the overall burden of that condition on the patient’s daily life. The Rand Short Form 36 is perhaps the best known of these.11 Because androgen deficiency may have a real impact on a man’s quality of life, a companion index focusing on the degree of bother generated by the condition would also be a welcome addition to the literature.

Conclusion

As more men present for androgen deficiency, a valid and reproducible method to assess their symptoms and to monitor response to therapy will be required. At present, two such indexes are available, and both have utility. Neither, however, has been submitted to truly vigorous psychometric testing. A methodologic framework exists to accomplish this task, and it may well be worth the effort to better diagnose, manage, and further study a condition that is likely to become more prevalent with time.

Main Points.

Symptoms of androgen deficiency include decreased sex drive, decreased energy, decreased ability to perform sexually, and mood changes.

Currently, two questionnaires have been proposed to evaluate men with low testosterone.

Development of a new symptom index and quality of life index using strict clinimetric and psychometric methodology would improve clinicians’ and researchers’ ability to screen for and monitor response to therapy in men with androgen deficiency.

References

- 1.Kaufman JM, Vermeulen A. Declining gonadal function in elderly men. Baillieres Clin Endocronil Metab. 1997;11:289–309. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(97)80302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Leary MP. Hard measures of subjective outcome: validating symptom indexes in urology. J Urol. 1992;148:1546–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Leary MP, Fowler FJ, Lenderking WR, et al. A brief male sexual function inventory for urology. Urology. 1995;46:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A suppl):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162:359–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morley JE, Charlton E, Patrick P, et al. Validation of a screening questionnaire for androgen deficiency in aging males. Metabolism. 2000;49:1239–1242. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.8625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinemann LAJ, Saad F, Thiele K, Wood-Dauphinee S. The Aging Males’ Symptoms rating scale: cultural and linguistic validation into English. The Aging Male. 2001;4:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika. 1951;16:29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al. Measuring disease-specific health status in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Measurement Committee of The American Urological Association. Med Care. 1995;33(4 suppl):AS145–AS155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]